CHAPTER 14

Toward a General Theory of Market Efficiency*

The Determinants of Market Efficiency

External Forces Influencing Markets Explained

Great Economists Can Learn a Lot from Value Investors

Markets Where External Disciplines Seem to Be Lacking

Market Efficiency and Fair Prices in Takeovers

The worst misconceptions about dealing in corporate finance are promulgated by the academic literature on the subject. One such misconception is the definitionx of a market. Most academicians seem to define a market as the New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ, or some other forum populated by outside passive minority investors (OPMIs). For the purposes of our discussion it is helpful to provide a general definition of a market:

A market is any financial or commercial arena where participants reach agreement as to price and other terms, which each participant believes are the best reasonably achievable under the circumstances.

Myriad markets exist and include the following:

- OPMI markets such as the New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ, and the various commodity and option exchanges.

- Markets for control of companies.

- Markets for consensual reorganization plans in Chapter 11.

- Institutional creditor markets.

- Markets for executive compensation.

For the past 50 years, financial academics have mostly operated on the assumption that financial markets are highly efficient. In a highly efficient market, the price of a common stock multiplied by the amount of shares outstanding reflects the underlying equity value of the company issuing that common stock. This is embodied in the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). Recently, behaviorists have challenged EMH based on the theory that investors sometimes make emotional, irrational, and stupid decisions. But even behaviorists seem to concede that if investors were rational, financial markets would be highly efficient. We disagree. Certain markets will always be inefficient versus EMH standards of efficiency.

A basic problem faced by financial academics, whether efficient market theorists or behaviorists, is that they are strictly top-down—studying economies, markets, and prices, not the underlying bottom-up fundamentals that really determine what a business might be worth and what are the substantive characteristics of the securities issued by that business.1 Put simply, the academics are best described as chartist-technicians with PhDs. Insofar as academics try to be value investors, they seem to believe to a man (or woman) that value is measured only by predictions of future discounted cash flows (DCF). They don’t grasp the fact that most firms and market participants have an overriding interest in wealth creation, not DCF, and DCF is only one of several paths usable to create wealth.

In bottom-up analysis, conclusions are drawn based on detailed analyses of individual situations—securities, commodities, companies—to ascertain whether gross mispricing exists or persists. As a general rule, such mispricings can arise out of one or more wealth-creation factors that are sometimes interrelated:

- Free cash flows from operations.

- Earnings, defined as creating wealth while consuming cash. For most firms (and governments), earnings can have long-term value only insofar as they are combined with reasonable access to capital markets.

- Asset and/or liability redeployments via mergers and acquisitions (M&A), contests for control, asset redeployments, refinancings, capital restructurings, spin-offs, and/or liquidations.

- Access to capital markets on a super-attractive basis such as selling common stock issues into a superheated initial public offering (IPO) market (e.g., the 2012 Facebook IPO) or having access to long-term, nonrecourse debt financing at ultralow interest rates (e.g., financing 80 percent of the cost of a Class A building, fully occupied under long-term leases entered into by creditworthy tenants).

Markets run an efficiency gamut. Some markets tend toward instantaneous efficiency, thereby comporting with the standards that are the essence of the EMH. Other markets tend toward a long-term efficiency but may never actually reach EMH efficiency. As a subset of this, it should be noted that a price efficiency in one market, say the OPMI market, is usually, per se, a price inefficiency in another market, say the takeover market. Some markets are inherently inefficient. Or to put it in another context, an efficient market in these situations means that certain market participants are virtually assured of earning very substantial excess returns on a relatively continual basis.

THE DETERMINANTS OF MARKET EFFICIENCY

Four characteristics determine whether a market will tend toward EMH-like instantaneous efficiency on the one hand or it will tend to be inherently inefficient by EMH standards on the other hand, or something in between.

Characteristic I: Market Participant

Insofar as the market participant is unsophisticated about value analysis, financed with borrowed money, and lacks inside information, that participant will face a market tending strongly to instantaneous, EMH-like efficiency. Insofar as an investor is well trained, well informed, and not influenced by day-to-day or short-run price fluctuations, that investor avoids being subject to an EMH-like efficiency.

Characteristic II: Complexity

How complex, or simple, is the security or other asset that is the object of the market participant’s interest? Insofar as the security is simple (i.e., it can be analyzed by reference to a very few computer-programmable variables), the asset pricing will reflect a strong tendency toward instantaneous, EMH-like efficiency. A further condition for EMH-like efficiency is that there be a precise ending date, such as when indebtedness matures, options expire, or a merger transaction is consummated. EMH-like efficiencies cannot exist if one concentrates on analyzing the common stock of a going concern with a perpetual life, or if one analyzes a troubled debt issue that will participate in a reorganization and the timing on the completion of such reorganization is relatively unknowable.

Insofar as specific securities are concerned, three types of issues tend to be characterized by instantaneous, EMH-like efficiencies:

Insofar as the analysis of the security entails complexity, EMH-type efficiencies tend to become unimportant factors.

Characteristic III: Time Horizons

If the participant is an OPMI involved in day-to-day trading, that participant will, in all probability, be faced with EMH-like efficiencies. If, however, the participant is a manager of a well-financed company and has a five-year time horizon during which time the company might choose to access capital markets (credit markets or equity markets), that participant will be involved in a market that is inherently inefficient by EMH standards. The manager who can control timing of when to access capital markets over a five-year period knows that there will be times when credit markets are very attractive for the company (i.e., interest rates are ultralow), and there will be times when it will be ultra-attractive to issue new equity in public offerings and/or mergers (i.e., an IPO boom).

EMH efficiencies exist only for participants in outside passive non-control markets who are heavily involved in daily, and even hourly, price movements of securities. The basic EMH concept is that market prices at any time reflect equilibrium. The old equilibrium changes to a new equilibrium only as a market absorbs new information. Thus, even securities that are analyzable by reference to a few computer-programmable variables are not priced efficiently if those securities lack very early termination dates. No EMH efficiencies can exist for investors with a long-term time horizon.

Again, in an efficient market, market prices determine the value of the company for all purposes. It is as William F. Sharpe, a Nobel laureate and a typical efficient market believer, stated in his book Investments: that if you can assume an efficient market, “every security price equals its investment value at all times.”2

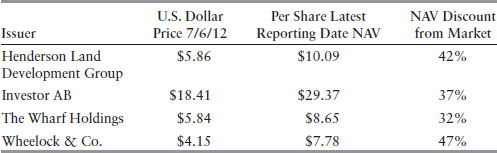

Where there are no reasonably determinate termination dates, markets for securities can be grossly inefficient even though the analysis is simple and few variables are involved. A good example of this revolves around the common stocks selling at huge discounts from net asset value (NAV) of companies that are extremely well capitalized, highly profitable, and with glowing long-term records of increasing earnings, increasing dividends, and increasing NAVs. The principal assets of these simple-to-analyze companies consist of private equity investments, marketable securities, and/or Class A income-producing real estate. The market data in Table 14.1 are as of July 6, 2012.

Table 14.1 Simple-to-Analyze, Extremely Well-Capitalized, and Highly Profitable Companies Selling at Discounts from NAV

The same analysis was pertinent for certain distressed securities on September 30, 2008, albeit that analysis was not as simple as that which exists for the high-quality common stocks cited in Table 14.1. The authors’ analyses indicated strongly that the probabilities were that General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC) senior unsecured loans were likely to remain performing loans. If not, upon reorganization or rehabilitation, the holder of these obligations likely would receive the common stock of, by then, a well-capitalized finance company or bank holding company.

GMAC notes due in 15 months were selling at 60, at a current yield of 13 percent and a yield to maturity of 55 percent. In the case of GMAC notes, it is important to mention that market price is unimportant for a holder who has not borrowed money to carry the securities. To earn excess returns here, all the analyst has to do is be right that the great weight of probabilities is that the notes would remain performing loans.

Characteristic IV: External Forces

How powerful are the external forces seeking to impose disciplines on the market participants and on the companies that are securities’ issuers? Insofar as the external forces are very powerful, prices will tend toward EMH-like instantaneous efficiencies. Competition among market participants, such as exists on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange or on NASDAQ, represents powerful external forces imposing restraints on OPMI day traders so that their returns will likely reflect EMH-like efficiencies. Insofar as the external forces are weak, markets will be inherently inefficient. Boards of directors are an external force imposing discipline on the compensation of top management executives. Boards tend to be weak, and thus corporate executives tend to earn excess returns consistently. Indeed, when external forces are weak, certain market participants (not only corporate executives) will earn excess returns consistently. This is part and parcel of the definition of a market where each participant strives to achieve the best returns reasonably achievable under the circumstances.

EXTERNAL FORCES INFLUENCING MARKETS EXPLAINED

Markets and market participants are very much influenced by external forces that impose disciplines on stockholders, companies, and management. The principal ones are:

- Competitive markets

- Regulatory agencies

- Governments

- Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), a self-regulatory organization

- Tax system

- Creditors

- Control stockholders

- Boards of directors

- Rating agencies

- Communities

- Labor unions

- Plaintiffs’ bar

- Federal and state courts

- Passive stockholders

- Auditors

- Corporate attorneys

When external forces impose very strict disciplines (e.g., government regulators, senior creditors, credit-rating agencies, and the plaintiffs’ bar), such strict regulation or control tends to stifle innovation and productivity. It is important to note that government does not have a monopoly on actions that stifle innovation and productivity. The same disease exists in the private sector, where, say, financial institutions follow overly strict lending practices.

When external forces impose little or no discipline (e.g., boards of directors rubber-stamping top management compensation and entrenchment packages or passive shareholders’ proxy votes), there tends to be created an environment that will be characterized by corporate inefficiency, frauds, and a gross misallocation of resources.

Who can deny that there is a need for balance in the imposition of disciplines? They should be neither too strict nor too soft. There is a school of thought stating that government regulation is ipso facto nonproductive and that private sector regulation is ipso facto productive (except for the plaintiffs’ bar). Nothing could be further from reality than such beliefs.

GREAT ECONOMISTS CAN LEARN A LOT FROM VALUE INVESTORS

After reading three volumes authored by great economists—The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (originally published in 1936, reprinted in 2011 by CreateSpace) by John Maynard Keynes, The Road to Serfdom (originally published in 1944, reprinted in 2007 by University of Chicago Press) by F. A. Hayek, and Capitalism and Freedom (originally published in 1962, reprinted in 2002 by University of Chicago Press) by Milton Friedman—one comes away with the impression that each was observing the earth with his naked eyes from 80,000 feet up. They missed a lot of details that are part and parcel of every value investor’s daily life.

To begin with, the three seem to recognize only three major forces directing the economy: capital (private owners, managers, or entrepreneurs), labor, and government. In fact, there are myriad other nongovernmental forces directing any industrial economy, including, among others, management control persons (separate and apart from private owners); creditors; rating agencies; boards of directors; professionals, especially attorneys and accountants; trade associations; and self-regulatory organizations such as FINRA.

For the three great economists, governments perform four functions: control the economy; regulate sectors of the economy; set fiscal policies (budget surpluses or deficits); and set monetary policies (interest rates and the quantity of money). In the twenty-first century, it seems a lot more productive in determining how the nation’s resources are to be allocated by the private sector to look at governments as engaged also in the following activities:

F. A. Hayek wrote The Road to Serfdom in the 1940s. The book was relevant for its time. The gravamen of its arguments was that command economies without a private sector, such as the Soviet Union then (and North Korea and Cuba today), just do not work. They deny their populaces not only economic well-being but also freedom. Of course, Professor Hayek was 100 percent right about this. However, in no way does it follow, as many Hayek disciples seem to believe, that government is, per se, bad and unproductive while the private sector is, per se, good and productive. In well-run industrial economies, there is a marriage between government and the private sector, each benefiting from the other. Since World War II, there have been a significant number of large command economies that have worked well by utilizing an incentivized private sector. Such economies include Japan after World War II, Singapore and the other Asian Tigers, Sweden, and China today.

For the value investor, the issue is not government versus the private sector. Rather, it is that, in accordance with Adam Smith’s invisible hand, those in control, whoever they are, should be incentivized appropriately. Government has a necessary role in determining how control persons are incentivized; and where the private sector will allocate resources in accordance with the invisible hand so that private control persons can maximize wealth for themselves, and also, by indirection, their constituents who are usually the owners of private enterprises. Whether one likes it or not, how and where Adam Smith’s invisible hand allocates resources through actions by private enterprises will be determined in large part by what government actions are. Should these government reactions be random, or at least in small part a product of planning? In the United States today it seems as if the federal government directs resources mostly by who has political clout. There is no question but that private enterprise, in its actions, is particularly sensitive to what the federal government does in terms of:

- Tax policy, both quantitatively and qualitatively

- Credit granting and credit enhancing

Control persons in the U.S. private sector are extremely sensitive to, and react very efficiently to, government policies in terms of taxation and in terms of credit granting and credit enhancing. Put in Milton Friedman’s context, Adam Smith’s invisible hand turns out to be more than random. It will be directed, at least in great part, by the government’s tax policies, and the government’s credit-granting policies. Put otherwise, what government policies contribute is important to the private sector’s determination of where the profits are.

Professor Hayek, however, seems to miss the opposite point that a free market situation is probably also doomed to failure if there exist control persons who are not subject to external disciplines imposed by various forces over and above competition: governmental, quasi-governmental and private sector. This is probably truer for financial markets than it is for commercial markets, but the point seems valid for both markets. Put simply:

Competition by itself tends not to be a strong enough external discipline to make markets efficient.

Where control persons are not subject to meaningful external disciplines, the following seems to occur:

- Exorbitant levels of executive compensation, a shortcoming rampant in the United States today

- Poorly financed businesses with strong prospects for money defaults on credit instruments, e.g., look at the insolvencies in recent years of Enron, General Motors, Chrysler, Lehman Brothers, and others

- Speculative bubbles, for example, the 1998–2000 IPO boom, the 2008–2009 burst of the real estate bubble

- Tendency for industry competition to evolve into monopolies and oligopolies where the companies involved have a large degree of insulation from competitive forces

- Corruption: for example, Enron, WorldCom, Refco

It ought to be noted, too, that many highly competitive industries happen not to be subject to meaningful price competition. Two such industries are money management and investment banking. In the investment-banking arena, there seems to be a universal 7 percent gross spread involved in bringing most new issues public. Also, a principal disadvantage of investing in distressed securities revolves around the rip-off of prepetition creditors by professionals, mostly lawyers and investment bankers. Competition to obtain professional engagements is intense. But no professionals in the distressed world, with very minor exceptions, ever seem to compete on price.

Disciplines are imposed on control persons operating in free markets by many, many more entities than just governments and competitors. The great economists mostly fail to recognize the existence of these other forces imposing discipline. Some tend to be harsh disciplinarians—creditors and rating agencies; and some seem to be very weak disciplinarians—passive owners of common stocks and boards of directors. These other forces imposing disciplines on control persons include the following:

- Owners

- Boards of directors

- Creditors—especially banks

- Rating agencies

- Labor unions

- Trade associations

- Communities

- Auditors

- Attorneys

Compared with value investors, great economists from Keynes to Modigliani and Miller seem largely oblivious to the very important role creditworthiness plays in any industrial economy.

The monetary and regulatory authorities influenced by the great economists seemed focused only, before the 2008–2009 meltdown, on gross domestic product and the control of inflation-deflation. They did not appear to worry, much, if at all about creditworthiness. Creditworthiness should have been the third leg of their analytical stool along with GDP and the control of inflation. Post 2009, this no longer seems true. Creditworthiness is now a real worry. As far as we can tell in mid-2012, corporations, in general (perhaps excluding depository institutions), probably have never been more strongly financed. On the other hand, governments—federal, state, and local—and consumers probably have never been less creditworthy than they are now. The ongoing crisis in the Eurozone in 2012 seems to reflect an absence of any useful ideas by economists and political figures to bring creditworthiness to national sovereigns—Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain. They do not seem to be even trying to create creditworthiness in the various rescue plans they are formulating.

Milton Friedman is gung-ho for free markets, unfettered by government intervention. As he states on page 22 of Capitalism and Freedom, “To the liberal, the appropriate means are free discussion and voluntary cooperation, which implies that any form of coercion is inappropriate.” Professor Friedman also states on page 13, “Fundamentally, there are only two ways of coordinating the economic activities of millions. One is control direction involving the use of coercion—the technique of the army and the modern totalitarian state. The other is voluntary co-operation of individuals—the technique of the market place.”

Professor Friedman, unfortunately, seems to have no background, or experience, in corporate finance. If he did, he would understand that public corporations just would not work unless, in the relationship between control persons and owners, certain activities would encompass voluntary exchanges while other activities would encompass coercion. So it is also on the national and global levels.

Also, given a background in corporate finance, Professor Friedman would have understood that there are three general ways for coordinating the economic activities of millions, not two:

In public corporations, there are certain activities that are essentially voluntary and others that are essentially coercive from the point of view of noncontrol securities holders.

Voluntary activities, where each person makes his or her own decision whether to buy, sell, or hold, encompass open market trading activities, certain cash tender offers, private purchase and sale transactions, and most exchanges of securities, including the out-of-court restructuring of troubled companies.

Coercive activities, where each individual security holder is forced to go along with a transaction or event, provided that a requisite majority of other security holders so vote, encompass proxy voting for boards of directors; most merger and acquisition transactions including reverse splits and short form mergers; certain cash tender offers; calls of convertible bonds or preferred stocks; the reorganization of troubled companies under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Act; and the liquidation of troubled companies under either Chapter 7 or Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Act.

We are as one with Professor Friedman that, other things being equal, it is far preferable to conduct economic activities through voluntary exchange relying on free markets rather than through coercion. But Corporate America would not work at all unless many activities continued to be coercive; security holders may get a right to vote (which vote may be pro forma and meaningless), but the security holders are coerced into going along whether they like it or not once a requisite vote has taken place. Incidentally, appraisal rights under state law, can be pretty meaningless in the scheme of things in merger and acquisitions, and can hardly be thought of as voluntary. Without some element of coercion, two undesirable things are bound to occur in a free market:

Assuming that the goal of an economy ought to be to maximize the average per capita income, and wealth, for its citizens (or residents), then adverse selection and hold-out problems have to modify, in certain areas, reliance solely on voluntary exchanges or the free market. Specifically, there are areas where, because of adverse selection and hold-out problems, the United States should not rely wholly on market mechanisms. These areas include the following:

- Medical Care: There is one good measure of how well cared for a population is; to wit, the average age of death. Here, the United States performs worse than most industrial economies. This seems a shame because the very best medical care in the world exists in this country for those who can afford it. The country would be much healthier if all its residents had access to decent medical care without adverse selection opt-outs.

- Social Security and Pension Plans: Clearly, the adverse selection problem will loom large if these retirement mechanisms are made wholly, or almost wholly, voluntary.

- Education: This country seems to be falling behind much of the rest of the industrial world in elementary through high school education, even though the United States probably still has the best university system in the world. There seems to be a real problem between allowing all parents to pick the school that their children should attend and the problem of adverse selection. Tough choice; we don’t have any easy answers.

Government regulation is not, per se, good or bad. There is good regulation and there is bad regulation. An example of good regulation is the Investment Company Act of 1940 as amended. An example of bad regulation is the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.

It ill behooves any successful money manager in the mutual fund industry to condemn the very strict regulation embodied in the Investment Company Act of 1940. Without strict regulation, we doubt that the industry would have grown as it has grown, and also be as prosperous as it is for money managers. Because of the existence of strict regulation, the outside investor knows that money managers can be trusted. Without that trust, the industry likely would not have grown the way it has grown. Outside investors know that the money managers cannot steal, cannot be involved in self-dealing, are limited in causing the fund to borrow money, fees charged are controlled, and the mutual fund must diversify as a practical matter. All of this occurs for the benefit of shareholders, while still permitting the money manager to prosper mightily from the receipt of management fees. This is an example of good, intelligent regulation. Messrs. Hayek and Friedman probably do not recognize the existence of such beneficial regulation.

On the other hand, Sarbanes-Oxley, or SOX, is an example of stupid, non-productive regulation. It seems to be regulation based on the belief that every company, every chief executive officer, and every chief financial officer, is associated with Enron, WorldCom, or Refco. Every company, therefore, should be subject to onerous regulation although such regulation does not seem to do anything, or much at all, about investor protection. The upshot of SOX is that it detracts mightily from the attractiveness of U.S. capital markets. No CEO or CFO likes being subject to liabilities that arise out of SOX. Smaller public companies cannot afford to comply with SOX. Few foreign companies are going to subject themselves to American jurisdiction unless they absolutely need access to American capital markets trading publicly owned securities. It is likely that Messrs. Friedman and Hayek believe most regulation is SOX-like. We do not. Some regulation is good; some bad. It’s all case by case.

Put otherwise, actions or expenditures by governments are not necessarily unproductive, and actions or expenditures by the private sector are not necessarily productive. Actions and expenditures ought to be gauged for usefulness on a case by case basis.

MARKETS WHERE EXTERNAL DISCIPLINES SEEM TO BE LACKING

Merchant Bankers (Promoters of Leveraged Buyouts)

Normally, people who put their own money into deals are known as principals, and those people who put deals together for fees but who do not have their own money in the deal are known as brokers. Merchant bankers are often brokers masquerading as principals. They usually invest none—or very little—of their own money in the deal, but they both collect their fees for putting deals together and obtain an equity interest in deals without any—or any material—money investment. Merchant banking has become a main activity for such major Wall Street names as Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.; Forstmann Little; Morgan Stanley; The Goldman Sachs Group, L.P.; and Citicorp Ventures.

Until the 1980s, principal broker-dealers, such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, believed that their best use of capital—both human and financial—was to employ capital in their own broker-dealer activities rather than to become involved in owning non–broker-dealer equities on a permanent or semipermanent basis. This attitude no longer exists, and much capital is now employed in structuring LBOs so that the merchant banker becomes a permanent or semipermanent investor in a corporation in which the merchant banker has meaningful elements of control.

Merchant banking has become increasingly competitive in recent years. This is to be expected, given the tendency toward efficiency that seems to exist in all markets. As far as can be determined, however, most of the better merchant bankers continue to earn excess returns as deal promoters, in part because there is so much outside money, run by passivists, such as pension funds that are eager to participate in LBOs. Merchant bankers structure fees for such investors so that they receive compensation as hedge-fund operators.

A typical setup for merchant banking activities is a limited partnership, a form also used for hedge funds engaged in venture capital investing, arbitrage, distress, and trading activities. Although terms may vary, a usual relationship is that the promoter—the general partner (GP)—receives an annual management fee of 1 to 2 percent of funds committed plus a profit participation of 20 percent of gains, sometimes accrued or paid only after the limited partners (LPs) receive a preferred return of 6 to 10 percent. For most limited partnerships, the final terms are arrived at after negotiations with a lead investor. In powerful limited partnerships (e.g., Kohlberg Kravis Roberts), the GP tends to dictate the GP-LP arrangements. Sometimes the GP gets to keep for itself various benefits, such as deal fees, rather than turning them over to the partnership.

Hedge-Fund Operators

Normally, hedge-fund operators run limited partnerships as GPs. There cannot be more than 100 LPs if the business entity is to avoid becoming a registered investment company (RIC); also, the partnership cannot have more than 35 LPs if it is to avoid becoming a registered investment adviser (RIA). Compensation to GP usually follows the merchant banker model outlined above: an up-front continuous fee of 1 to 2 percent of assets managed per annum, plus a profit participation after the limited partnership has earned a bogey of, say, 6 to 10 percent per annum. Profit participation can range from 20 to 50 percent. Those who do such hedge-fund deals include:

- Merchant bankers–LBO promoters

- Risk arbitrageurs

- Vulture funds

- Venture capitalists

- Real estate syndicators

- Oil and gas syndicators

- Movie producers

There is probably some uniformity in the financial hedge-fund market revolving around 1 (a 1 percent annual management fee) and 20 (a 20 percent profit participation). Promoters’ compensations may be different in nonfinancial areas:

- Before 1986, real estate limited partnerships had more like 3 to 5 percent management fees and 50 percent participation in profits plus property management fees. It seems that since the real estate tax-shelter (TS) debacles between 1986 and the early 1990s, promoters’ compensation has gravitated more to the economic equivalent of 1 and 20, whether the real estate promoters are being compensated as GPs or as managers of real estate investment trusts (REITs).

- Oil and gas syndications used to have promoters’ participations based on the concept of one third for one quarter: Put up 25 percent of the money invested for a 33 percent interest, plus management and operators’ fees.

- There probably are norms for promoters’ compensations in show business and movie deals, usually under the rubric of producer’s compensation.

Governance of limited partnerships is almost always strictly in the hands of GPs. The norm is that LPs have fewer governance rights than exist for OPMI shareholders of corporations. This is especially true for publicly traded limited partnerships.

In raising funds, it is better from the promoter’s point of view to raise funds for a blind pool: After funds are committed, the promoter can invest in whatever he or she chooses. This is not always possible, since many potential LPs want to invest only in specific deals.

The limited partnerships referred to here are privates exempt from SEC registration under Regulation D because each has fewer than 35 investors. In the 1980s, publicly registered limited partnerships were common, especially in real estate and in oil and gas.3

Bailouts for LPs are varied. For example, the sales pitch for real estate tax shelters prior to the 1986 amendments to the Internal Revenue Code was that returns would be made up of tax losses, perhaps some cash income followed by sale at a terminal date, whereas for a venture-capital limited partnership, the bailout revolves around taking portfolio companies public at super prices in future initial public offerings (IPOs).

Investment Bankers

Investment bankers earn huge fees providing services in three areas:

Securities Salespeople

Since the advent of competitive commission rates in 1975, an increasing emphasis of Wall Street sales forces has been to offer exclusive products with large gross spreads rather than to emphasize the purchase and sales of securities in secondary markets. For example, the fairly typical gross spread on the 1986 IPO of Boston Celtics, L.P. was $1.29 per unit, which would compare with a commission in the secondary market charged a customer of, say, anywhere from 2 cents a unit, where the customer obtained a discount to a maximum of 40 cents per unit for 1,000 units acquired from a full-service nondiscounting broker-dealer. Of the $1.29 gross spread, anywhere from one third to one half might have ended up as security salesperson’s compensation. It seems that for some years, many security salespeople earned excess returns marketing exclusive products with large gross spreads, including real estate and oil and gas limited partnerships, load mutual funds, and IPOs. There are probably tremendous institutional pressures within the financial community to keep coming up with products that will continue to permit sales forces to earn excess returns. Not only are the commissions earned on IPOs large, but also most IPOs are designed to be easy sells in that at the time of initial offering, demand exceeds supply.

Money Management

Control of funds for basically passive investments is an inordinately profitable business with very little price competition, whether such control is through registered investment companies or registered investment advisers. There are three principal sources of excess returns when a firm has assets under management: sales load, management fees, and control of portfolio trading. In addition, those who control funds are in a position to deliver excess returns to other controllers, by, for example, appointing outside directors and choosing attorneys and accountants for funds.

There is a ready market for the sale of companies with funds under management at prices, which in 2011 ranged from 2 to 5 percent of funds managed. Table 14.2 shows funds under management for selected participants.

Table 14.2 Funds Under Management for Selected Companies (As of the End of 2011—Approximate Figures)

| Company | Billions of Dollars |

| BlackRock Global Investors | $3,650 |

| State Street Global Advisors | $2,000 |

| The Vanguard Group | $1,700 |

| Fidelity Investments | $1,500 |

| PIMCO | $1,400 |

| Dreyfus Corporation | $1,260 |

Promoters in Trading Environments

A discussion of promoters in trading environments is more often the purview of those involved with academic finance and EMH rather than of value investors. Players earning excess returns persistently from trading activities include the following:

- Market makers

- Users of free or almost free credit balances at broker-dealers

- Certain spread lenders

There is confusion in the academic literature on whether excess returns are earned on sunk costs or present values. As a practical matter, stock exchange specialists can earn excess returns forever, as can the owners of television stations, because once they have the franchise to earn excess returns, no one is in a position to enter the market and cause entrenched players to give up their returns.

Top Corporate Managements

If boards of directors do not impose discipline on top managements’ compensation, no other entity will. The steepest slope in the industrial world seems to be in the United States between the earnings of managements and those of employees.

Controlling management compensation is the province of boards of directors, but discipline imposed on management compensations by boards of public companies seems virtually nonexistent. De facto, board appointments are made by managements that are unlikely to appoint either people who are not friends or who are troublemakers. Delaware is the leading corporate state. There are virtually no cases in Delaware involving allegations of excessive management compensation. There is an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rule denying corporate tax deductions for certain management compensation in excess of $1 million per year per individual, but the rule is easily circumvented.

Top executive compensation has several components:

- Salaries

- Perks

- No-risk or low-risk equities, especially through stock options

- Certain transactions, including leasing properties to company or providing other services for compensation

- Participation in merchant banking activities, such as management buyouts (MBOs)

- The chance to employ friends and relatives

- The control of corporate governance, including management entrenchment

Other Professionals Who Tend to Enjoy Excess Returns

Other professionals can earn what seem to be excess returns:

- Defense attorneys

- Plaintiffs’ attorneys (in the United States, the existence of class actions and absence of security for costs helps promote excess returns)

- Management consultants

- Tax advisors

- Bankruptcy attorneys

Other professionals who are probably less well compensated than investment bankers and attorneys include the following:

- Business brokers

- Appraisers

- Providers of litigation support (expert witnesses)

Two groups of professionals that provide truly essential services, yet seem to be grossly undercompensated are auditors and indenture trustees. Auditing has been a notoriously unprofitable profession in this country, given the legal developments in accountants’ liability. With the prerequisite of independence, auditors are held to far higher standards than are other professionals, especially investment bankers and attorneys. Such high standards are essential. Without reliable audit standards, the U.S. economy probably would cease to function because it would probably be impossible to grant commercial credit.

Corporate Monopolies and Oligopolies

Many corporations—the Coca-Cola Company, Google, Apple Computer, Intel—earn superior returns consistently, relatively insulated from competition and other external forces that could impose disciplines.

MARKET EFFICIENCY AND FAIR PRICES IN TAKEOVERS

Fair is defined as that price, and other terms, that would be arrived at in a transaction between willing buyers and willing sellers, both with knowledge of the relevant facts and neither under any compulsion to act.

The problem is that in many transactions for companies whose common stocks are publicly traded, especially MBOs, the real world situation is one of willing buyer–coerced seller; where the buyer is also an agent who is supposed to represent the interests of the seller. The seller, whose interest is supposed to be represented by the buyer, is the public shareholder, or OPMI. The buyer, at least in part, is usually corporate management and/or control shareholders.

Coercion of OPMIs occurs in two ways:

Therefore, the purpose of fairness opinions, and fairness in general, ought to be to simulate a willing buyer–willing seller environment even though there tends to be in the real world, a willing buyer–coerced seller environment. Many appraisals by investment banks, and others, do not recognize this, and market price often will be the principal determinant of the transaction price even where there is a willing buyer–coerced seller situation. Put otherwise, in rendering many fairness opinions, little or no consideration is given to the important question: What is the company worth to the buyer? For example, in Delaware, the leading corporate state, there are no appraisal rights for OPMIs in transactions involving an exchange of common stocks where both issues of common stock are publicly traded. Also in Delaware courts, fair value excludes consideration of values arising out of the merger itself; in effect, do not consider or weigh what the deal might be worth to the buyer.

What makes an OPMI a willing seller? A premium over market.

What makes a control person a willing buyer? A price that represents a discount from what the buyer thinks the business is really worth to him, or his institution.

Thus, EMH notwithstanding, there frequently is a huge gap between the price that would satisfy a willing seller and the price that would satisfy a willing buyer.

Given that OPMIs are willing sellers and control persons are willing buyers, it is logical to assume that most of the time there will be a wide disparity between what a willing seller will assume is a fair price and what a willing buyer will assume is a fair price. Each group tends to focus on different factors. The OPMI seller will tend to focus on those corporate variables most likely to affect near-term market prices, to wit, short-term outlooks for earnings, earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), dividends and industry identification. Control buyers, on the other hand, tend to focus on how they can finance the transaction, the quality and quantity of resources in a business, and long-term outlooks.

Obviously, takeover prices tend to be a lot more favorable for OPMIs when the price arrived at is the result of competitive bids rather than only negotiations between parties. A sale of assets under Section 363 in a Chapter 11 case is always a bidding contest where open bidding more or less assures a fair price. The problem for most healthy companies is that most corporate endeavors have to be negotiated—transactions are complex. Contracts for negotiated transactions almost always contain no shop, break-up fee, and topping fee clauses. These discourage the conversion of negotiated transactions into bidding contests.

The argument is made by OPMI representatives, including the Plaintiff’s Bar, that in an MBO-type transaction, the control persons should be obligated to pay the OPMIs that price which represents what the business is actually worth to the buyer.

We disagree. If control persons were unable to buy businesses at prices that represent discounts for them, then buying interest by control persons would dry up.

SUMMARY

A market is any financial or commercial arena where participants reach agreement as to price and other terms, which each participant believes are the best reasonably achievable under the circumstances. Four factors determine whether a market will tend toward EMH-like instantaneous efficiency on the one hand or it will tend to be inherently inefficient by EMH standards on the other hand, or something in between. These factors are (1) who the market participant is; (2) how complex, or simple, is the security or other asset that is the object of the market participant’s interest; (3) the time horizons of the participants; and (4) external forces imposing discipline on the participants. We review each of these factors and use them to highlight misleading simplifications that great economists have brought to bear in the conventional understanding of several economic problems. We also provide a list of examples of markets where external disciplines seem to be lacking, and illustrate our framework in the analysis of fair market prices in takeover transactions.

* This chapter is based on material in Chapter 7 of Distress Investing: Principles and Technique by Martin J. Whitman and Fernando Diz (© 2009 by Martin J. Whitman and Fernando Diz), and ideas contained in the 2005 4Q and 2007 1Q letters to shareholders. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

1 These substantive characteristics of securities were discussed at length in Chapter 4 of this book.

2 William F. Sharpe, Investments, 3rd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1985), p. 67.

3 See the excellent book by Kurt Eichenwald, Serpent on the Rock, which was published in 1995 (New York: HarperCollins) and describes business practices at Prudential Bache Securities.