CHAPTER 17

Academic Finance: Modern Capital Theory*

Equilibrium Pricing Is Universally Applicable

The Outside Passive Minority Investor Is the Only Relevant Market

Diversification Is a Necessary Protection against Unsystematic Risk

Value Is Determined by Forecasts of Discounted Cash Flows

Investors Are Monolithic: Their Unitary Goal Is Risk-Adjusted Total Return, Earned Consistently

Risk Is Defined as Market Risk

Macro Considerations Are Important

Creditor Control Is a Nonissue

Transaction Costs Are a Nonissue

Free Markets Are Better than Regulated Markets

The Outside Passive Minority Investor Market Is Better Informed than Any Individual Investor

Markets Are Efficient or at Least Tend Toward an Instantaneous Efficiency

As we have explained earlier in this book, our approach to value investing entails buying what is safe and cheap by an outside passive minority investor (OPMI). The techniques used in value investing are the same or similar to those used in control investing and distress investing. All three involve fundamental finance (FF). Two areas of FF involve passive investing: value investing and credit analysis. The other areas of FF involve active investing and obtaining control or elements of control in distress investing, control investing, and primary and secondary venture capital investing. In contrast to fundamental analysis, academic finance is focused on market prices in organized markets rather than fundamental analysis where the focus is the understanding of a business and the securities issued by that business.

In FF, what is refers to the use of analytic techniques that concentrate on the known situation of a company—the quality and quantity of resources in a company, with little or no concentration on forecasts of relatively near term flows (say, over the next 12 months), except for sudden-death events.

Safe refers to the survivability of a business as a business (or securities issued by the business) without any reference whatsoever to price volatility of the securities issued by that business. Safety is measured mostly by strong financial positions; by the quality of resources, if the investor is interested in such junior securities as common stocks; by strong covenant protections; and by reasonable quantitative characteristics in terms of asset coverage or earnings coverage, or both, if the investor is interested in owning corporate debt.

Cheap means an acquisition price for a common stock that appears to represent a substantial discount from what the common stock would be worth were the company a private business or a takeover candidate. In the case of a debt instrument, cheap means an estimated yield-to-maturity, or yield-to-workout, that is at least 500 basis points greater than could be obtained from a credit instrument bearing about the same level of ultimate credit risk.

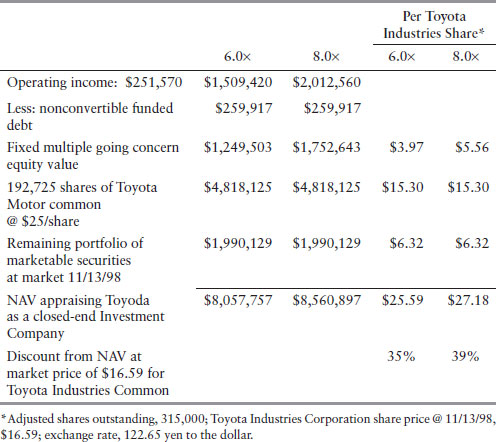

In November 1998, Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, Ltd. (since renamed Toyota Industries) common stock, listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, appeared to be a good example of a common stock that was safe and cheap based on what is because the company was well financed and represented a way of buying into the common stock of Toyota Motor, a blue-chip automotive manufacturer at a discount of perhaps 35 to 40 percent. Toyota Industries common was trading at about 2,300 yen per share, or about $16.5 to $17 U.S. dollars. Its adjusted balance sheet, expressed in U.S. dollars, was as shown in Table 17.1.

Table 17.1 Balance Sheet for Toyota Industries Corporation (Adjusted NAV in $000s)

In 2012, many common stocks of well-financed companies were selling at readily ascertainable discounts. Such common stocks included Capital Southwest, Investor AB, Cheung Kong Holdings Company, Henderson Land Development, and Wheelock & Company as well as Toyota Industries.

Believers in modern capital theory (MCT) as embodied in the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) and efficient portfolio theory (EPT) never would have valued Toyota Industries operations and the Toyota Industries portfolio of marketable securities in the first place. That is not what they do. EMH and EPT analysis would have been restricted to studying historical market prices for Toyota Industries common and perhaps historical ratios of price to earnings or cash flow. If the discount of market price for Toyota Industries common relative to Toyota Industries net asset value (NAV), which was based largely on the market value of securities held in Toyota Industries’ portfolio, were to be explained, the explanation would probably revolve around investor expectations. Furthermore, the discount would probably be viewed as irrelevant, not related at all to either Toyota Industries cash flows or the outlook for the Tokyo Stock Market. These two factors would have been deemed much more likely to influence the near-term price performance of Toyota Industries common than would be the existence of a large discount from workout value.

In November and December 1995, Kmart senior unsecured debentures and trade claims seemed to be good examples of credit instruments that were safe and cheap based on what is. On average, these senior issues traded in public and private markets at prices averaging around $74. These instruments had average yields to maturity of around 18 percent in a market where BB industrial credits were trading at yields to maturity of around 9 percent and BBB obligations were trading at yields to maturity of around 8 percent. BBB is the lowest grade credit that Standard & Poor’s, as a rating agency, defines as Investment Grade. Standard & Poor’s defines a BBB credit as follows: “An obligation rated BBB exhibits adequate protection parameters. However adverse economic conditions or charging circumstances are more likely to lead to a weakened capacity of the obligor to meet its financial commitment on the obligation (as compared with credits rated AAA, AA, or A). Obligations rated BB, B, CCC, CC, and C are regarded as having significant speculative characteristics.” BB is the highest-grade obligation to be characterized as speculative.

It was problematic at the time as to whether Kmart would have to seek relief under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. If Kmart did seek Chapter 11 relief, all cash service on the Kmart unsecured debt would cease. The odds, however, seemed good that if Kmart ever did enter Chapter 11, the workout values for these Kmart instruments in a reorganization would be at least $100 or more likely $100 plus accrued interest. This confidence in the ultimate workout was based, in great part, on the seniority enjoyed by these unsecured debentures and trade claims. There were no secured credits outstanding.

MCT probably would not be involved at all in the specific analysis of Kmart Debt—or other issues of distressed debt—in terms of details about covenants and reorganization processes. The MCT analysis would revolve around studies of the markets for distressed debt and macro statistics about overall rates of money defaults.1

THE MCT POINT OF VIEW

The previous section is only an example of the vast differences in approach between a value investor and those who subscribe to MCT. In value investing, securities are examined from multiple points of view, including the company itself and control shareholders. By contrast, MCT looks at securities analysis solely from the point of view of outside passive minority investors (OPMIs).

MCT appears to be useful in describing a special case with two components:

- Credit instruments without credit risk (e.g., U.S. treasuries).

- Derivative securities such as convertibles, options, and warrants. (The values for derivatives are determined by prices of other securities rather than by any analysis of the underlying values attributable to a security, such as a common stock.)

- Risk arbitrage securities where the workouts are short run (i.e., there are relatively determinant workouts within relatively determinant periods of time such as where there is an outstanding tender offer, an outstanding voluntary exchange of securities, or a merger transaction subject to a scheduled stockholder vote).

The basic problem with MCT is that it tries to make a general law out of what is really a very narrow special case. MCT teachings are not very helpful for value investing, where the analysis becomes relatively complicated regardless of whether the object of the analysis involves corporate control factors or buy-and-hold passive investing. Indeed, the underlying assumptions governing the EMH and EPT are either downright wrong or just plain misleading for value investing purposes. Since many (if not all) of these beliefs are so pervasive in the accepted conventional wisdom, we had to discuss many of them in other chapters of this book. However, we thought the reader would benefit from a brief discussion of many of them. Such basic assumptions of MCT focus on the following 20 different beliefs:

EQUILIBRIUM PRICING IS UNIVERSALLY APPLICABLE

William F. Sharpe, a Nobel laureate and a typical efficient-market believer, stated in the third edition of his book Investments that if you assume an efficient market, “every security’s price equals its investment value at all times”.2 This observation could not possibly be more incorrect or more misleading for value-investing purposes. For value investing, an OPMI market price, especially for a common stock, does not necessarily have any relationship to the price that ought to prevail were the security to be analyzed as issued by a company that is to be involved in mergers and acquisitions (M&As), hostile takeovers, going-private transactions, or liquidations. Not only is there no necessary relationship between prices that prevail in OPMI markets and prices that prevail in other markets (e.g., leveraged buyout [LBO] markets), but there ought not to be any relationship because by and large, different factors (e.g., borrowing ability versus near-term reported earnings) are used to determine value in these discrete markets, and insofar as the same factors are used (e.g., availability of control versus dividend policy), they are weighted quite differently.

There are even differences in pricing within value investing itself. Appropriate prices will differ depending on whether the value investor is involved with passive value investing, risk arbitrage, or control investing. Within control investing, pricing parameters tend to vary depending on whether the control buyer is primarily a financial buyer or a strategic buyer. Strategic buyers generally can afford to pay more.

Value investing is an offshoot of control investing. In value investing, a passive investor makes use of the same variables and phenomena in making investment decisions as does the activist, except that the passive investor is not going to have any elements of control that would permit the creation of extra value for the investor in the forms of various edges described in Chapter 22: something off the top (SOTT), such as salaries and perks; an ability to finance personal positions on an attractive basis, as with other people’s money (OPM); and an ability to undertake attractive income tax planning through tax shelters (TSs). The value investor therefore ought to be a lot more price conscious than the control investor, since the latter is often in a position of being able to create excess benefits and excess returns even when overpaying, by many standards, for particular assets. Put otherwise, as far as price is concerned, control investors and OPMIs operate in different markets with different price structures.

To assume equilibrium pricing for all purposes and all markets is to put yourself in a straitjacket precluding your undertaking any analysis of most of what goes on in the financial community—M&As, IPOs, LBOs, and contests for control.

To be involved with value investing, whether as a control person or a value investor, you had best obtain detailed knowledge about bottom-up fundamental factors affecting companies, about securities, about capital markets, and about government regulations and laws. Moreover, in many situations, you should also obtain elements of control over companies; over the processes companies go through, or over both, or else decline to make any investment at all. For example, getting some elements of control over the reorganization process, even if only a negative veto, can be almost essential for success in Chapter 11 investing. This is in contradistinction to MCT, in which the focus is on the behavior of securities prices and markets rather than on obtaining detailed knowledge (and maybe even influence) about the companies in which you might invest.

Risk arbitrage is an investment process involving workouts of securities that are expected to create relatively determinant values in relatively determinant periods of time. One feature that tends to distinguish risk arbitrage from value investing is that although both are passive, investors would be unable to participate in risk arbitrage markets in general unless they are willing to pay up. Risk arbitrage markets tend to have pricing much more attuned to MCT-type efficiencies than do value investing markets. In value investing, a buy-and-hold strategy without determinable workouts, investors desiring to earn excess returns persistently might not be willing to pay more than 50 percent of what they believe the present value of the security would be in a workout or takeover. By contrast, persistent excess returns might be available for risk arbitrageurs whose pricing is equal to 90 to 95 percent of an estimated near-term workout value.

In MCT, there is a belief that markets are efficient or, more accurately, that markets tend toward an instantaneous efficiency. In value investing, there is also the belief that all markets tend toward efficiency. In numerous markets, though, that tendency toward efficiency may take a long time to become effective, and there are frictions that may preclude those efficiencies from ever becoming evident. For example, investors think there are long-term tendencies that ought to result in a material shrinkage in the discount at which Toyota Industries common sells from its NAV, but they do not know about how long it will take for the discount to narrow, the form it will take (could or would Toyota Industries spin off into an investment company its portfolio of marketable securities?), or if it will happen at all. Here, the long-term tendency toward efficiency is quite weak. As a matter of fact, in Toyota Industries–type situations, the security is deemed to be attractive not because of a prediction that the market price will become efficient (i.e., reflect underlying values) but rather because at the price paid, the probabilities that excess returns will be earned over the long term with relatively little investment risk ought to be pretty good.

In simple trading situations (e.g., risk arbitrage), the tendency toward efficiency is very strong and tends very much to be instantaneous. Concerning the statement that certain markets tend toward instantaneous efficiency, there is no argument between value investing and MCT, but about the MCT statement that all or most markets tend toward instantaneous efficiency, value investors disagree.

In the EMH, the descriptive adjective is consistently; in value investing, it is persistently. Persistently means a majority of the time and on average over a long period; consistently means all the time. In value investing, the participant deals in probabilities, never in certainties.

In academic finance, there seems to be just one right price for a security, but in value investing, the right price can cover a wide gamut. A fair price in value investing would be defined as that price, and other terms, that would be arrived at after arm’s-length negotiations between a willing buyer and a willing seller, both with knowledge of the relevant facts and neither under any compulsion to act.3 The one sine qua non that causes an OPMI stockholder to become a willing seller is a premium above OPMI market price; the one thing that causes a control buyer to become a willing buyer is a value for the control of the company that is more than the all-in price the control buyer has to pay. Often the spread between a willing seller price and a willing buyer price can be—and ought to be—huge.

Trying to gauge timing, especially about general stock market levels, seems an important consideration in MCT. In value investing, the investor does not gauge timing but rather takes advantage of whatever the market situation happens to be at that time. For MCT, timing is crucial; investors must gauge when prices might change in OPMI markets. One of the great advantages of value investing, especially for control people involved with well-financed companies, is that as activists, they tend to obtain complete control of timing in terms of deciding when to go public or when to go private. For noncontrol investors holding a portfolio of securities selected using value analysis precepts, there seems to be a strong tendency toward being indifferent to timing. If the fundamental analysis is good enough, market performance will be okay, if not for individual issues, then for portfolios consisting of five or more different issues. Put otherwise, if market performance for the portfolio is unsatisfactory, it would not be because of poor market timing but rather because the specific analyses using value investing techniques were flawed.

Special problems exist for the EMH given the concentration on OPMI market price as a universal measure of true value:

- The EMH fails to distinguish between an unrealized market loss and a permanent impairment of capital. In EMH, they are one and the same.

- The EMH fails to distinguish between a paper profit and an inability to cash in on gains for many non-OPMI activists, such as managements of companies that have just gone public via an IPO.

- The EMH fails to understand the huge population of OPMI investors whose needs are met by a contractually assured cash income from interest payments rather than from total return. For example, the vast majority of investors in tax-free bonds have a primary interest in the income generated from holding those bonds rather than in market price. Indeed, most investors in tax-free bonds hold such instruments as lockups and tend to be oblivious to what market prices might be. Tax-frees, also known as munis, are a huge market. These are bonds issued by state and local governments and their agencies. As of March 2012, approximately $3.7 trillion principal amount of munis were outstanding.4

- The EMH adopts unrealistic views in such matters as employee stock options. In value investing, and according to common sense, the value of a stock option benefit to a recipient of those options clearly has no necessary relationship to the cost to the company to issue the options.

- In the EMH, there is a failure to understand that market prices self-correct over time for performing loans with contractual maturity dates.

For value investing, a given price for a security can represent both a tendency toward inefficiency in one market and a simultaneous tendency toward efficiency in another market. For example, examine the price behavior for the 6265 publicly traded closed-end investment companies registered under the Investment Company Act of 1940, as amended as of December 31, 1997. These 626 issuers’ assets consisted by and large of only marketable securities. Most have all common stock capitalizations, their expense ratios are limited because of regulation, and many, if not most, are managed by mutual fund managers. Prices for mutual fund shares are always at least equal to NAV (as measured by the OPMI market prices of assets) or at premiums of up to 9 percent above NAV because of sales loads. Over 80 percent of the closed-end investment-trust common stocks in contrast trade at a discount from NAV and have traded at discounts consistently. This strongly demonstrates a tendency toward inefficiency in the OPMI market. If the OPMI market were efficient in all contexts, the market prices of the closed-end common stocks would equal precisely the market value of the assets of the closed-end funds, since these assets consist wholly of marketable securities just as is the case for mutual funds. This is the case for no-load mutual funds, not because of any external market efficiencies but because the mutual funds offer and redeem common shares at NAV; there are no other markets for mutual fund shares. At almost no time, however, have any of these closed-end investment-trust common stocks sold at a discount of as much as 35 percent below NAV. This demonstrates a tendency toward efficiency in the hostile takeover market because if shares were available at much greater discounts, hostile takeovers might make sense, even granting that it appears that every closed-end fund currently in existence has adopted significant shark repellents (management entrenchment devices that insulate incumbent control people).

Academic theories that OPMI prices are right, or correct, prices in nonarbitrage markets and therefore good allocators of resources revolve in part around a view that if the OPMI price is wrong, sophisticated investors who know real value will come into the OPMI market and, through their buying, make the price right or correct. Such a view ignores the fact that many, if not most, sophisticated long-term investors and insiders view untrained OPMIs trying to outperform the market consistently as a population to be exploited in going-public or going-private transactions and in providing to insiders SOTT, such as huge executive compensation packages. Such a view also misconceives what sophisticated investors do and do not do. First, they do not necessarily buy in OPMI markets. Many acquire equity positions not by buying common stocks in OPMI markets but rather by receiving, for no monetary consideration, executive stock options exercisable at the OPMI market price existing at the date the options were granted. Insiders generally want OPMI market prices to be low on the date options are granted, but most would prefer to receive options when a company is private and the exercise price of the option might be book value, rather than after the company goes public in an IPO at a price that might be 5 to 10 times book value. Most sophisticated control investors probably would never be interested in purchasing any common stock in the OPMI market at any price if that common stock did not deliver elements of control over the business. Rather, these people, and institutions, engage in control-type transactions away from the OPMI market, which gets for them promoters’ compensations in the context of:

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Hostile takeovers

- Going public

- Going private, LBOs, managed buy outs (MBOs)

- Restructuring troubled companies

- Compensation for passive money management

In contrast to the conventional other financial disciplines, an underlying tenet of value investing is that for most purposes most of the time, many common stock prices in OPMI markets are either going to be far above liberal estimates of what corporate values would be if no OPMI market existed and that many other common stock prices in OPMI markets are going to be far below conservative estimates of the corporate values that would exist for private businesses and takeover candidates. In an active world, control people and quasi-control people arbitrage these differences between OPMI pricing and corporate values. When very high OPMI market prices can be realized, new issues are sold to OPMIs as IPOs and, say, real estate tax shelters. The dotcom bubble, before it burst in early 2000, was an example of crazy high prices for IPOs. In 1996, it seemed as if medical device companies that had received preliminary Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval might receive a pre–public offering value, based on the price at which the issuer was to go public, for their equity of as much as $100 million, even though the businesses had virtually no revenues and were reporting losses. When very low OPMI prices exist (probably in combination with corporations’ being reasonably well financed), existing common stock issues are acquired from OPMIs in going-private, M&A, and hostile takeover transactions (e.g., the 1990 LBO of Big V Supermarkets).

For the vast majority of firms (electric utilities used to be a notable exception), the variables used to value a business are different from those used to evaluate a common stock trading in an OPMI market. When the same variables are examined—say, the near-term earnings outlook—their importance is weighted quite differently, so there is no basis for concluding that OPMI market price is the best or even a reasonable measure of corporate value.

THE OUTSIDE PASSIVE MINORITY INVESTOR IS THE ONLY RELEVANT MARKET

For MCT, there seems to be but one relevant market: the OPMI market. In value investing, there are myriad relevant markets, including the following:

- Outside passive minority investor traders’ market

- Outside passive minority investor investment markets

- Markets for control of companies

- Leveraged buyout markets

- Consensual plan markets in Chapter 11 reorganizations

- Credit markets

- Initial public offering markets

- Markets for settlement of litigation

Efficient pricing in one market—the OPMI market, for example—is per se inefficient pricing in another market—the takeover market in value investing, for example. Almost any control buyer seeking to obtain control of a company whose common stock is traded in an OPMI market will have to offer a premium over the OPMI market prices if he or she is to attempt to acquire control using a cash tender offer or exchange of securities. A premium, too, probably (but not necessarily) has to be paid by a control buyer acquiring large blocks of common stock for cash in the open market or private transactions, or by a buyer using corporate proxy machinery and acquiring control through a voting, rather than direct purchasing, mechanism.

The importance of market price varies with the situation in value investing. Although market price may be all-important to the OPMI holder of common stock, it tends to be far less important to the holder of control common stock or to the unlevered holder of a performing loan.

DIVERSIFICATION IS A NECESSARY PROTECTION AGAINST UNSYSTEMATIC RISK

Diversification as a hedge against unsystematic risk is a central tenet of EPT. It is part and parcel of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). For value investing, diversification is only a surrogate—usually a poor one—for detailed knowledge about the corporation and its securities, control, and price consciousness and also, in some cases, ability to obtain attractive financing for a transaction.

Whether a value investor ought to concentrate or diversify depends on how much knowledge, control, outside (preferably nonrecourse) finance, and bargain pricing the investor can obtain. Certainly, followers of the EMH ought to diversify. The EMH is addressed to those who study securities market prices and have no detailed knowledge about corporations, to noncontrol OPMIs, and to people who utterly lack price consciousness because they assume that the OPMI market price is an equilibrium price with universal applicability. That diversification seems particularly appropriate for MCT passivists, however, does not mean that diversification is also completely inappropriate for others. Following is an investor matrix describing, in general terms, groups and individuals that should concentrate (top) to those (bottom) that should diversify:

- Business school graduate using all his or her resources—personal and financial—to start up a new business he or she will head

- A company, now in one line of business, that is undergoing an M&A

- Leveraged buyout fund

- Venture capital fund

- Investors in high-grade performing loans seeking reasonable amounts of cash income

- Knowledgeable value investors

- Knowledgeable risk arbitrageurs

- Typical OPMIs

- Investors using the teachings of MCT

SYSTEMATIC RISK EXISTS

Part of EPT is the belief that systematic risk—common factors that will affect all companies whose common stocks are publicly traded—exists. Such factors include the business cycle, changes in market indexes, interest rates, and inflation. Systematic risk also is a nonstarter for value investing. Each of the above factors has different effects on different companies and the securities issued by those companies. A severe industry-wide depression helped rather than hurt Nabors Industries in the late 1980s. Nabors, which enjoyed strong finances, was able to acquire a huge fleet of oil and gas drilling rigs on a bargain-basement basis, in great part because virtually all its competitors had questionable financial strength. Reduced market prices in the 1970s, caused by weak general markets, permitted Crown Cork and Seal to repurchase its own common stock at much more attractive prices than would have otherwise been possible.

General inflation and the increased costs associated with it probably would prevent a lot of new competitors and even existing competitors from spending the huge amounts of money it would take to become a new entrant or an expanded entity in diesel engine manufacture in order to compete with Cummins Engine. It is simply a gross oversimplification to assert that there exist common factors that would affect all American businesses. This is the tenet underlying systematic risk.

Systematic risk may in fact exist in a nonfinancial context. All corporations and all investors might fare poorly if the areas in which they are located are rife with political instability and physical violence. These have been unrealistic scenarios for industrialized countries, especially the United States, which, it is hoped, will continue to be the case.

VALUE IS DETERMINED BY FORECASTS OF DISCOUNTED CASH FLOWS

For MCT, the worth of a common stock is the present value of future dividends. For value investing, by contrast, the worth of a common stock is the present value of a future cash bailout, whatever the source of the bailouts. Cash bailouts can come from the benefits of control, sale to an OPMI market, distributions to shareholders, or various conversion events, including sale of control of the business or refinancing on attractive terms.

Brealey and Myers stated in Principles of Corporate Finance, that “only cash flow is relevant” (p. 96).6 They are wrong, certainly for value investing purposes. Copeland, Koller, and Murrin stated in Valuation—Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, “the manager who is interested in maximizing share value should use discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, not earnings per share, to make decisions” (p. 72).7

The vast majority of projects that make sense create positive cash flows for a corporate owner over the life of the projects viewed as standalones. Very few corporations operating as going concerns, however, ever create cash flows consistently. Indeed, most are relatively consistent cash consumers that have to finance the cash deficits they create by obtaining outside capital, usually borrowings, on a regular basis. In value investing, there are four approaches to wealth creation, which are discussed in more detail in Chapters 5 and 6.

In any event, value investing is founded on a balanced approach. Here there is no primacy of forecasted future flows, whether cash or earnings. Rather, the interrelated elements needed to ascertain value are quality of resources in the business, quantity of resources, and long-term wealth creation power. There are four general interrelated ways to create corporate wealth using a value investing approach:

- Cash flows available to security holders. Corporations probably create this fewer times than most people think.

- Earnings, with earnings defined as creating wealth while consuming cash. This is what most well run corporations do and also what most governments do. Earnings cannot have a lasting value unless the entity remains creditworthy. Also, in most cases, in order to maintain and grow earnings the corporation or government is going to have to have access to capital markets to meet cash shortfalls.

- Resource conversions. These areas include massive asset redeployments, massive liability redeployments and changes in control. Resource conversions occur as part of mergers and acquisitions, contests for control, the bulk sale or purchase of assets or businesses, Chapter 11 reorganizations, out-of-court reorganizations, spinoffs, and going privates including LBOs and MBOs.

- Super-attractive access to capital markets. On the equity side, this includes initial public offerings (IPOs) during periods such as the dotcom bubble. On the credit side, this includes the availability of long-term, fixed-rate, non-recourse financing for income producing commercial real estate.

COMPANIES ARE ANALYZED BASICALLY AS GOING CONCERNS; INVESTORS IN MARKETABLE SECURITIES ARE ANALYZED AS INVESTMENT COMPANIES

For modern capital theorists, businesses are to be analyzed as strict going concerns, engaged in continuing operations, managed pretty much as they always have been managed, financed pretty much the way they always have been financed. Valuations are based on determining the present value of estimated future flows, whether cash or earnings.

For value investing, though, businesses are to be analyzed both as going concerns and resource conversion vehicles engaged in deploying assets, in redeploying assets, and in refinancing activities, including M&As. Valuations are based not only on determining cash or earnings flows but also on examining the company’s separable and salable assets and gauging the company’s prospects for accessing capital markets at ultra-attractive pricing.

Corporate analysis is complicated by the assumptions that no universal price equilibrium exists; that most businesses are appropriately analyzed as both going concerns engaged in day-to-day operations and resource conversion companies employing and redeploying assets and financing and refinancing liabilities; and that most businesses are likely, over time, to engage (or be engaged) in such conversion activities as M&As, hostile takeovers, and goings-private.

Once a corporation is viewed as a resource conversion complex rather than a strict going concern, then estimating future flows, whether cash or earnings, tends not to remain the sole, or principal, factor in a valuation. Rather, measuring the quality and quantity of resources existing at a particular moment becomes important.

Once it is assumed that no universal price equilibrium exists, the form of consideration paid may become much more important than the nominal value of a transaction, as measured by OPMI market prices. Which would be more valuable to a control seller, $100 million cash or $180 million market value of restricted common stock of the acquiring corporation? Besides price, in any merger or LBO transaction, the following factors will almost always be important considerations:

- Tax impact on important parties to the transaction

- Acquirer’s ability to finance the transaction

- Accounting treatment, especially if the surviving company is to remain public

- Representations and warranties of each side

- Other contract terms (e.g., bust-up fees)

- Control issues as they affect corporate executives

- Probability and timing of closing the transaction

- Transaction costs

- Feasibility of the surviving corporation

- Financial incentives to insiders

- Probable impacts on OPMI market prices

- Probable reactions of the risk arbitrage community

- Minority shareholder litigation

- Government approvals

In MCT, there seem to be two principal exceptions to viewing the firm as a strict going concern. The first exception is when the value of a corporation’s assets (and sometimes liabilities) can be measured by reference to OPMI market prices. Thus, in the EMH, a portfolio of performing loans will be valued at market insofar as it is deemed to be “available for sale.” In this case, the future interest income potential of the portfolio is ignored. Even though assets that trade in OPMI markets are almost always marked to market under the EMH, there are exceptions when OPMI market prices are not in sync, as is the case for closed-end investment companies, which almost always trade at discounts from the OPMI market values of their portfolios.

The second exception concerns M&A accounting. Purchase accounting is a resource conversion concept that blends into the financial picture not only results from operations but also results of the price paid to acquire another going concern. If that price is ultrahigh compared with the acquired company’s NAV, future income accounts may be burdened by a noncash charge for goodwill impairment, which would reflect management’s mistakes in their role as investors as opposed to operators.

In MCT, there does not appear to be any recognition that analysis based on a going concern approach results in different, and often opposite, conclusions from those that arise out of a resource conversion approach. In value investing, this dichotomy is recognized. Both going concern analysis and resource conversion analysis are valid. Which should be weighed more highly depends on the security being analyzed and the position of the investor undertaking the analysis.

Although noninvestment companies are evaluated, under academic finance, mostly as going concerns striving only to create cash flows from operations, investors in the securities of those concerns are evaluated on the basis of total-return concepts—flows plus valuation of portfolio holdings at market. Under MCT, however, investors are treated as the equivalent of investment companies even though many investors may have as their principal objective the creation of income from interest and dividend payments, which, of course, for analytic purposes, makes them the equivalent of going concerns.

INVESTORS ARE MONOLITHIC: THEIR UNITARY GOAL IS RISK-ADJUSTED TOTAL RETURN, EARNED CONSISTENTLY

Investors are anything but monolithic in value investing. Most will have multiple—or at least a mixture of—investment objectives:

- Cash return versus total return

- Long-term OPMI versus trading OPMI

- Control versus OPMI

- Control total return, usually including benefits in the forms of SOTT and access to attractive financing

Successful value investors as part of their analysis, understand other relevant points of view: those of long-term buy-and-hold OPMIs, trading OPMIs, the corporation itself, managements, control shareholders, governments, vendors, lenders, employees, investment bankers, accountants, and local communities. They know it is important to figure out who has the clout and what has to be done to satisfy the clout as part of the process of earning excess returns.

Investors and investment advisers concentrating on asset allocation and diversification seem per se to be speculators who start out with the following assumptions:

- Outside passive minority investor price is an equilibrium price.

- Outside passive minority investor prices will change as conditions change; therefore, focus on buying what is popular, when it is popular, or likely to get popular.

- Do not obtain much knowledge of the specific company or the securities it issues.

- Be nervous.

Asset allocators who believe in academic finance allocate investments in equity portfolios by concentrating on outlooks for particular industries and on outlooks for specific geographic locations; the better the near-term outlook, the more funds are allocated in that direction. In value investing on the other hand, asset allocation is price driven rather than near-term-outlook–driven; the cheaper an equity appears to be, on the basis of the three-pronged balanced approach, the greater the proportion of funds invested there.

MARKET EFFICIENCY MEANS AN ABSENCE OF MARKET PARTICIPANTS WHO EARN EXCESS RETURNS CONSISTENTLY OR PERSISTENTLY

MCT’s underlying assumption that market efficiency means no consistent or persistent returns for any one participant has no basis in reality, except for OPMIs who analyze and invest using MCT precepts. Indeed, control investing is about getting something out of being involved with securities over and above the rights and privileges that flow from being the passive owner of a common stock, a fee interest in real estate, a preferred stock, a loan, a trade receivable, or a leasehold interest. How that something extra is obtained in corporate America and in the financial community is a subject worthy of systematic study and is examined in Chapter 14’s discussion of promoters’ and professionals’ compensations.

The only rational definition of efficiency for markets in which little or no discipline is imposed by external forces is that excess returns have to be earned persistently and even consistently in that market and that abuses will surface.

It can be theorized that no excess returns are ever earned in any market in which an asset value is marked to market. Earnings here determine the market value, so anytime earnings increase, market value increases correspondingly. Thus, no excess returns are earned, at least as a percentage of the market value of the earnings attributable to those assets. This may not be a useful concept, however, when assets that give rise to the excess returns are not marketable (e.g., top management salaries arising out of management control of proxy machinery, plus charter and bylaws full of shark repellents entrenching management in office). For value investing, it is equally relevant to measure excess returns both by examining returns as a percentage of cost or by depreciated cost, and also by examining returns as a percentage of market value. Weighting assigned to cost or market is dictated by specific circumstances.

For MCT, efficiency means that all information affects an OPMI market price, so that no participant in an OPMI market earns excess returns consistently. For value investing, efficiency means that there are not only OPMI trading markets in which MCT-type efficiency exists but also myriad markets in which little or no external disciplines are imposed, so that participants in those markets earn excess returns persistently. Indeed, in these markets with little or no imposed external disciplines, if excess returns were not earned persistently, those markets, under value investing would be inefficient.

Activists seeking to earn excess returns persistently ought to seek out those fields in which external disciplines are weak or absent. The following forces are supposed to impose disciplines that in turn impose curbs on market participants’ earning excess returns:

- Competitive markets

- Boards of directors

- Customers

- Vendors

- Labor unions

- Communities

- Social and religious consciousness

The following markets seem to be the least disciplined areas in the United States today:

- Top management compensations

- Plaintiffs’ attorneys

- Investment bankers

- Bankruptcy professionals

- Leveraged buyout packagers and promoters

- Mutual fund management companies

- Hedge fund operators

There are problems with U.S. financial markets, albeit they appear to be far and away the best that have ever existed. Here are a few of the problem areas:

- Promoters’ compensation seems far too high under the U.S. financial system.

- Debtors, especially debtor managements, get too much entrenchment, protection, and compensation when restructuring public companies either out of court or in a Chapter 11 case.

- Initial public offerings tend to be grossly overpriced for their actual business value.

- Overwhelming institutional pressures exist to give resources to issuers able to deliver large gross spreads to the financial community, the merits of a particular issue notwithstanding.

- Regulation of trading markets is onerous.

- Investment company regulation is particularly onerous.

- The tax code is a nightmare, albeit administratively highly efficient compared with other economies. The code’s sheer complexity is a burdensome problem, but the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) code must be complex to produce one final result: what the tax bill will be. Other measurement systems, especially Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), do not have to be complex. GAAP do not give final results; rather, they are only objective benchmarks that analysts use as one tool to determine approximate values and aid in examining alternative courses of action. From a taxpayer’s point of view, a taxable event has three elements: (1) What is the tax rate? (2) Does the taxpayer control timing as to when the tax might become payable? (3) Does the event that gives rise to the tax also create the cash with which to pay the tax?

GENERAL LAWS ARE IMPORTANT

MCT and indeed economics in general place primary emphasis on promulgating general laws. Although other, more mature social sciences, such as law and psychology, admit to the importance of general laws, they focus instead on individual differences that exist on a case-by-case basis. Value investing does promulgate general laws, but they have important exceptions. A first example is this: As a general law in value investing, quarterly earnings reports are unimportant; however, reported earnings for a quarter may be paramount to companies seeking to issue common stock in a public offering or in a merger transaction. A second example concerns price: In value investing, the general law is to try to buy bargains; that is, do not pay more than 50 to 60 percent of what you believe the security would be worth were the business a private entity or a takeover candidate. The exception is that you ought to be prepared to pay up (i.e., have a different pricing standard) if you are involved with risk arbitrage. Here, the 50 to 60 percent guideline might become 90 to 95 percent.

To the user, the ultimate value of a value investing approach compared with the value of academic finance depends on how realistic and useful the various assumptions are. Depending on context—say, day trading compared with a passive buy-and-hold strategy—each approach has validity. For day trading, a MCT approach seems a lot more useful than a value investing approach; for a passive buy-and-hold strategy, value investing seems more useful than MCT. Obviously, this book is based on the belief that for most participants in most investment processes most of the time, value investing is more valid and useful than is academic finance. Furthermore, it strongly supports the belief that value investing ought to be the context of choice from a public policy point of view when promulgating securities law and regulation, when deciding lawsuits involving valuation and disclosure issues, and when promulgating accounting principles in accordance with GAAP or IFRS.

In any specific value investing analysis, the individual differences become much more important than the general laws. Thus, this book refers to “most of the time,” not “all of the time.” For example, in the management of corporate affairs, it is most productive most of the time to take actions based on management’s beliefs about the long-term consequences of those actions; in most cases, this would entail ignoring near-term considerations insofar as those factors detract from creating cash flows or long-term corporate values. If the corporation needs to finance by seeking outside equity capital, however near-term considerations might have to dominate. Specifically, most of the time, corporate managers ought to manage so as to increase cash flows and basic corporate wealth even if this means sacrificing current earnings per share as well as reported earnings per share for the quarterly periods immediately ahead. If the corporation or its insiders need to raise equity capital in the short term though—say, over the next 12 months—it might be better to manage to increase earnings per share and to do things Wall Street analysts like, such as having the company operate as a pure play in an industry rather than be diversified. The risk of not being short-run conscious here seems to be not so much the prices at which issues of equity securities might be marketed by corporations or insiders but whether such issues can be sold at all.

In addition, in value investing, what you think of underlying factors tends to be more important than what you think other people think most of the time. What other people think—the conventional OPMI market wisdom—does tend, however, to become of critical importance to such activists as issuers and promoters when they seek access to outside capital markets, especially equity markets. Seeking such access tends to be an irregular, occasional event for most companies, rather than a continuous process, except for certain types of issuers—which now seem to be a minority of issuers—such as electric utilities, growing finance companies, and many real estate investment trusts (REITs).

Trade-offs are tricky in the value investing scheme of things. In a simple world, it might be said that super-pricing for IPOs results in a misallocation of resources because it results in overinvestment in growth companies in hot industries and underinvestment in other parts of the economy. Perhaps this is so, but it seems obvious that the super-pricing available for IPOs has in effect created a rather dynamic venture capital industry in the United States. During the 1990s, such investments, possibly in combination with an increased supply of technically competent people freed up because of defense cutbacks, seem to have made this country the premier economy for innovation and start-ups associated with such high-tech areas as digital communications and biotechnology. Certainly, the IPO phenomenon has made many of these high-tech companies real businesses because as a result of the going-public process, they have become extremely well financed. Also, the popularity of IPOs has resulted in dedicated managements. Most IPOs raise money only for the company. For insiders to realize a cash bailout after an IPO, the business generally has to prosper. Initially, all an IPO at $10 per share does for insiders who acquired common stock at 2 cents a share is give them cocktail party points in discussing their net worth. To convert that paper net worth to a meaningful realization probably requires in most cases that the underlying business actually prosper.

For most existing public companies, the sale of new issues of common stock has tended to be a marginal undertaking in terms of amounts of funds raised as compared with seeking other sources of outside capital in various credit markets, ranging from bank loans to other institutional borrowings to public debt offerings. Selling new issues of common stock is quite important, however, in that equity funds provide a borrowing base permitting more senior borrowings on more favorable terms for an issuer than would otherwise be the case. Probably most important, most activist managers properly believe that OPMI markets are capricious in terms of (1) pricing at any given time versus business value and (2) the availability of OPMI markets as a source of new equity capital on a reliable basis. Raising equity money by accessing capital markets tends to be quite expensive, ranging from, say 2 to 8 percent of the funds raised. Most of the new equity capital for businesses is therefore derived from retained earnings rather than the sale of newly issued common stock. In doing so, most active managers properly focus first on the needs of the business, both aggressive and defensive, and only second on the needs or desires of OPMIs. There is no substantive consolidation.

RISK IS DEFINED AS MARKET RISK

For MCT, risk means market risk—what will happen to the price of a security—but for value investing, risk means investment risk most of the time—what will happen within the business and to the terms of the securities it has issued without regard to the market price of those securities. Value investors basically calculate risk by measuring what can go wrong with the business against the price paid for a buy-and-hold security. For passive investors acquiring securities using a fundamental finance approach, there are four steps in the analysis of a security, shown below in descending order of importance:

For most analysts most of the time, steps 1, 2, and 3 will be so important that step 4 can be ignored completely.

MACRO CONSIDERATIONS ARE IMPORTANT

Given the political stability that prevails in the United States and most of the industrial world, it is rare indeed in value investing that macro considerations become important in analyzing and investing in the deal. Macro considerations were probably important in 1929, 1933, 1937, 1974, and 2008–2009. Draconian macro events seem infrequent enough that the value investor can safely ignore them. Another reason to ignore them is that no one seems to be able to forecast them.

In academic finance, it is believed that such macro factors as the level of interest rates, the level of various stock indices, gross domestic product (GDP), employment data, and inflation, indices are virtually always extremely important inputs into most valuation processes. For value investing, individual business performance has always been more important in determining securities price performance on either a buy-and-hold or a control basis than have been macro factors, except in maybe the aforementioned specific years.

In considering general conditions in value investing, it is apparent that since World War II, industry-wide depressions have occurred with amazing persistency. The difference between now and the 1930s, though, is that now there is little or no domino effect from these depressions. Between 1973 and 1998, almost every U.S. industry went through depressions as severe as anything experienced by the particular industry during the 1930s, even though the U.S. economy was generally prosperous. These severe depressions affected, among others, the automobile industry, aluminum, steel, machine tools, energy, banking, real estate, savings and loans, row crops, airlines, water transportation, retail trade, and nuclear-dependent electric utilities. Typically, many of the publicly traded common stocks of companies in depressed industries become ultracheap, as measured by both the quality and quantity of business resources, even as they appear quite expensive measured by price to current earnings and price to earnings forecast for the period just ahead.

CREDITOR CONTROL IS A NONISSUE

In MCT, the appropriate capitalization seems to be driven by OPMI needs and desires, whereas in value investing, it is driven by needs of the company, bailout of the clout, or both. Capitalization is discussed more fully in Chapter 7 on creditworthiness.

Most corporations borrow money. They will be governed very much in what they do about shareholder distributions because of what their contractual agreements are with lenders as well as their probable sensitivity to lenders’ needs and desires. Such lenders are both financial institutions and providers of trade credit. Also increasingly affecting shareholder distributions in recent years has been the emergence of mutual funds and individuals holding high-yield junior corporate debt and preferred stock.

TRANSACTION COSTS ARE A NONISSUE

In academic finance, transaction costs seem to be all but ignored except for bankruptcy costs. For value investing, there are virtually no financial transactions in any arena with which Wall Street is involved—except maybe discount brokerage (and that is doubtful)—that do not involve huge transaction costs. For certain participants in financial processes, huge transaction costs mean huge transaction incomes, even after overhead.

FREE MARKETS ARE BETTER THAN REGULATED MARKETS

Lots of people—maybe most—would deny that resource allocation is the primary justification for the existence of the investment processes. Most would probably say that the primary purpose for the existence of the financial community is to provide investor protection, especially for holders of OPMI common stock. They seem to reason that if such investor protection were provided, it would, a priori, result in efficient resource allocation. This book does not agree with this view. It cannot be assumed that efficient asset allocation will result if investment decisions are made by the investing equivalent of kelp and plankton of the marine food chain—uneducated passive reactors whose goal in investing is to outperform a market consistently.

The most important things to realize about any financial system in any economy is that it is going to be replete with elements of inefficiency, misallocation of resources, frictions, and basic unfairness and that there will always be trade-offs. For example, it is a summum bonum for an economy to operate in an environment with high levels of integrity for securities trading markets, but overwhelming evidence indicates such integrity cannot be attained without onerous regulation, which obviously has counterproductive elements. The high degree of regulation of trading on the floor of the NYSE is but one example of this. As far as can be seen, the U.S. financial system’s allocation of resources is good enough, even if it is acknowledged that from a long-term company-oriented point of view, OPMI markets grossly misprice a very large number—probably a majority—of common stocks.

Nonetheless, a historical focus on investor protection has had tremendous secondary benefits for all U.S. capital markets:

- The integrity of U.S. trading markets is superb.

- The U.S. public disclosure system is superb.

- Oversight of fiduciaries and quasi-fiduciaries is pretty good.

- Senior credit markets, both public and private, tend to be pretty efficient, partly because corporate disclosures, especially audits, have become so good.

Conversely, the focus on investor protection (i.e., OPMI protection) has also had unfortunate consequences in the United States:

- Generally accepted accounting principles have been bastardized. They are used to seek truth in reported earnings rather than to provide knowledgeable investors with objective benchmarks to be used as essential tools of analysis.

- Crazy legal theories, have proliferated, exemplified by fraud-on-the-market lawsuits, which postulate that plunges in OPMI market prices are evidence of insider fraud because the common stock never would have achieved high prices in efficient markets in the first place if insiders had made full disclosures.

- Stockholder litigation, driven by attorneys’ fees rather than merits, has become commonplace.

- Many corporate managements and activists have become far more oriented toward short-run results than is really productive for the economy.

- For issuers that need access to capital markets, there tends to be a primacy of reported earnings; that is, what the numbers are becomes more important than what the numbers mean, especially short term.

Efficient-market theories, based on a view that the constituency to be served is the short-run–conscious, unsophisticated OPMI, have caused numerous problems. They were the proximate cause of the derivatives debacle of 1987 because of the failure to distinguish between credit risk and other risks. Also, they fostered an environment in which OPMIs do not believe they have to know anything.

There are three principal roles of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and these involve some conflicts with free markets. If the Securities and Exchange Commission did not foster regulation in these areas, the climate for OPMI investment might be as poor as it seems to be in most emerging markets. These roles are:

- To provide fair and orderly trading markets

- To provide disclosures to investors

- To exercise oversight over fiduciaries and quasi-fiduciaries

THE OUTSIDE PASSIVE MINORITY INVESTOR MARKET IS BETTER INFORMED THAN ANY INDIVIDUAL INVESTOR

Value investing is useless unless practitioners assume that for their purposes, they are better informed than the OPMI market. This is not an unrealistic assumption, since most passive value investors are long-term buy-and-hold investors. Short-run market considerations, the lifeblood of the EMH, are unimportant in value investing. It is not that the value analyst has access to superior information vis-à-vis the OPMI market but rather that the value analyst uses the available information in a superior manner.

MARKETS ARE EFFICIENT OR AT LEAST TEND TOWARD AN INSTANTANEOUS EFFICIENCY

Efficient markets are a fundamental precept of the EMH. In value investing, all markets tend toward efficiency. Occasionally, there are markets, like the OPMI trading market that tends strongly toward instantaneous efficiency. Insofar as a market is characterized by instantaneous efficiency, there is no argument between value investing and academic finance, but most markets do not seem close to obtaining instantaneous efficiency most of the time. Because this is so, there is actually a wide chasm between MCT and value investing even granting a universal tendency toward efficiency in all markets. In many markets (e.g., mutual fund management fees or top management compensation in many public companies), the tendency toward efficiency seems so weak that it might be realistic to ignore it.

SUMMARY

There are substantive differences between academic finance as embodied in the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) and modern capital theory (MCT), and fundamental finance (FF) in general, and value investing in particular. We provide an exhaustive discussion of each and every substantive difference pointing out the narrower and more limited focus of the academic finance approach to investment problems.

* This chapter contains original material, and parts of the chapter are based on material contained in Chapter 2 of Value Investing by Martin J. Whitman (© 1999 by Martin J. Whitman), and ideas contained in the 1999 1Q, and 2003 2Q letters to shareholders. This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

1 See the work of Professor Edward I. Altman as a prime example of this school of thought.

2 William F. Sharpe, Investments: An Introduction to Analysis and Management, Third Edition (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1985).

3 See Chapter 14.

4 “Volker Rule Could Prove to Be ‘Devastating’ for Munis,” Investment News, March 13, 2012.

5 As of February, 2012. Data from the Closed End Fund Association.

6 Richard Brealey and Stuart C. Myers, Principles of Corporate Finance, Fourth Edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991).

7 Thomas E. Copeland, Tim Koller, and Jack Murrin, Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies (McKinsey & Company, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1992).