CHAPTER 25

The Economics of Private Equity Leveraged Buyouts

The 2005 Acquisition of Hertz Global Holdings and Subsequent Events as a Prime Example

Super-Attractive Access to Capital Markets

Cash Payments to Sponsors and Sponsor-Controlled Funds

Sponsors Attuned to the Needs of Bankers and the Wall Street Underwriting Community

This chapter discusses the 2005 leveraged buyout (LBO) of the common stock of Hertz Global Holdings at a relatively high price earnings (P/E) ratio and a substantial premium above book value. Despite mediocre operating results subsequent to the LBO, the Hertz Global Holdings transaction seems to have been quite remunerative for the LBO sponsors and their investors. In our view this success is attributable mostly to the fact that time and again the sponsors enabled holders of Hertz Global Holdings common stock to obtain super-attractive access to capital markets. Also sponsors and investors received two large dividends where the funds for paying one of the dividends came from a loan with liberal covenants, and for the other, from the proceeds of an underwritten common stock offering to the public.

THE 2005 ACQUISITION OF HERTZ GLOBAL HOLDINGS AND SUBSEQUENT EVENTS AS A PRIME EXAMPLE

The essential element of any LBO is the purchase of 100 percent of the outstanding common stock of the target company, almost always for cash, thereby eliminating the interests in the company of the selling stockholder(s). In December 2005 Ford Motor Company, the sole stockholder of a company since renamed Hertz Global Holdings (Hertz), sold its entire interest in the common stock of Hertz for approximately $2,295,000,000 cash. The private equity group purchasing Hertz consisted of a consortium, or club, put together by three sponsors (sponsors): Clayton Dubilier and Rice (CDR); Carlyle Group (Carlyle); and ML Global Private Equity Fund (Merrill Lynch).

From the point of view of the sponsors, and the sponsors’ investors, the Hertz buyout has proved to be highly successful despite the fact that from 2006 through June 30, 2012, Hertz has been a quite mediocre operation reporting losses under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) in three of the six years from 2006 through 2011. From 2006 to date, the sponsors on behalf of themselves and the investment funds managed by them have extracted $4,973,500,000 in cash either from Hertz or from sales of Hertz common stock in public offerings. At the time of this writing, the investment funds still hold 110,009,479 shares of Hertz common with a market value of almost $1,800,000,000.

SUPER-ATTRACTIVE ACCESS TO CAPITAL MARKETS

Clearly, the principal contributing factor to the success of the sponsors and their investors has been the sponsor’s enormous ability and enormous credibility in accessing capital markets on a super-attractive basis. This has enabled Hertz time and again to finance cash payouts to investment funds managed by the sponsors. This ability to access capital markets on an attractive basis seems pervasive in the LBO industry for not only CDR, Carlyle, and Merrill Lynch, but also for a number of other sponsors.

The goal of the Hertz sponsors seems two-pronged:

- First maximize sponsors’ and their controlled investment funds net present values (NPV) by extracting from Hertz and the public markets for the benefit of the sponsors and investment funds as much cash as possible as soon as possible.

- Second, keep control of Hertz and extract large amounts of fees and emoluments from Hertz, probably largely or completely for the benefit of the sponsors and their appointed Hertz directors.

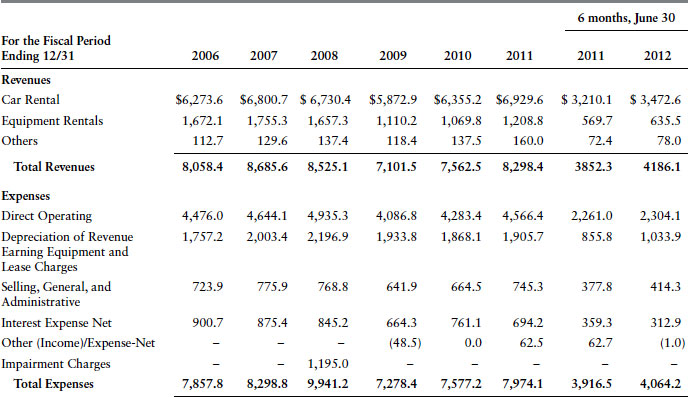

Table 25.1 summarizes the Hertz income accounts for the periods from calendar 2006 through June 30, 2012.

Table 25.1 Hertz Global Holdings Income Statement (000)

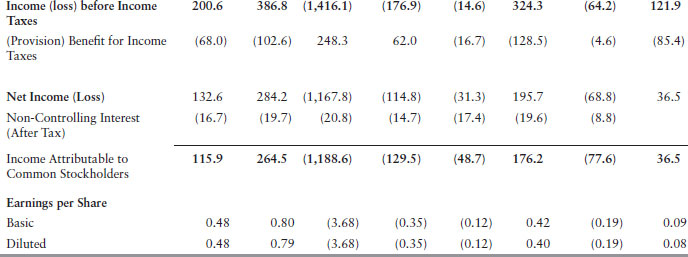

In marketing a $1,950,000,000 unsecured loan in 2012, Hertz mostly ignored GAAP income attributable to common stockholders, but instead focused on corporate earnings before interest, income taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). EBITDA do not seem to be figures with much economic significance for potential unsecured creditors, simply because in Hertz’s case the bulk of depreciation charges do not appear to be noncash charges. Rather Hertz is required to replace its revenue-generating equipment continuously; cars become obsolete within relatively short time periods and industrial equipment ages with use. Table 25.2 shows that depreciation of revenue earnings equipment plus proceeds from the disposal of revenue equipment barely exceeded revenue earnings equipment expenditures for the six years and six months ended June 30, 2012. The excess of depreciation of revenue earnings Equipment plus proceeds from the sale of such equipment exceeded capital expenditures by only $1 billion over the six-and-a-half-year period.

Table 25.2 Selected Consolidated Cash Flows, Hertz Global Holdings, Inc.

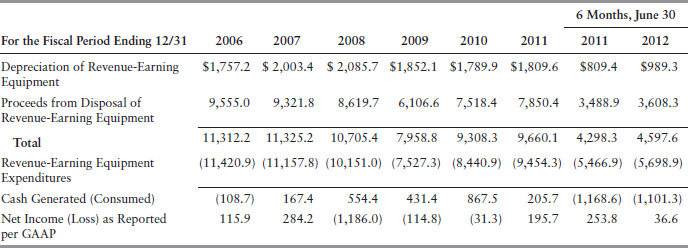

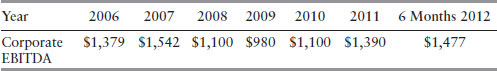

In contrast, Hertz focuses on corporate EBITDA for the six years and six months in marketing unsecured debt in 2012 as shown in Table 25.3.

Table 25.3 EBITDA for Hertz Global Holdings, Inc. (000)

Despite these mediocre operating results, Hertz was able to borrow $1,950,000,000 to fund the $2,200,000,000 acquisition of Dollar Thrifty Group (DTG) which closed on November 16, 2012. Such borrowing is on an unsecured basis where a one-year bridge loan may convert into an unsecured eight-year bullet (i.e., nonamortizing) loan. In our view, the Sponsors and Hertz management deserve great plaudits for their ability to consummate such a financing, even at interest rates, which could reach 57/8 percent plus fees. This seems to be an excellent example of the sponsors’ credibility and talent for accessing capital markets on a super-attractive basis. If we were the lenders, and given Hertz’s record in the last six and one half years, there is no question that we would lend for the DTG transaction at a price near the principal amount only if we believed we were adequately secured.

The ability to market unsecured debt reflects super-attractive access to capital markets. While the acquisition of DTG may make Hertz’s future much brighter than would be the case where the analyst relied heavily on Hertz’s operating record from 2006 to 2012, this ought not to be much of a consideration for unsecured creditors acquiring debt instruments priced at or near the principal amount, which in this case is equal to the call price. The unsecured credit instrument has no material price upside potential, and the holder has to be convinced the loan will be a performing loan. In that environment a potential creditor would not rely on outlooks based on a base case analysis or an optimistic analysis. Rather the creditor should reach his conclusions based on a reasonable worst-case analysis. Given Hertz’s six-and-one-half year record, it seems quite risky to pay the principal amount to become an unsecured creditor of Hertz based on any reasonable worst-case analysis. Indeed, it appears as if there might have been a question about Hertz’s ability to remain solvent after the economic meltdown occurred in late 2008 and early 2009. An unsecured creditor using a reasonable worst-case analysis probably would conclude that economic conditions could at some indeterminate time in the future again approximate the 2008–2009 economic meltdown in either North America or Europe or both.

CASH PAYMENTS TO SPONSORS AND SPONSOR-CONTROLLED FUNDS

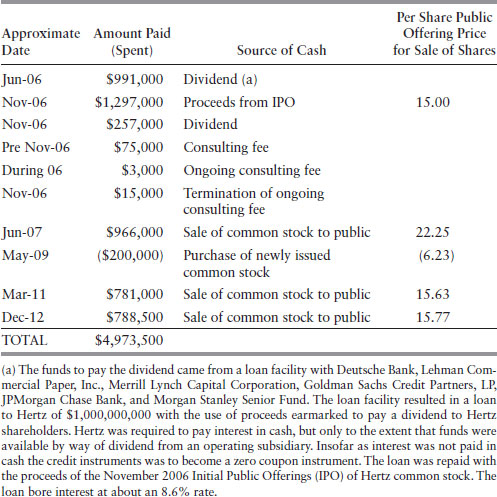

The ultraskillful use by the sponsors of capital markets is demonstrated in Table 25.4, which summarizes cash payments to sponsors and sponsors-controlled investment funds from 2006 through December 2012.

Table 25.4 Cash Payments to Sponsors and Controlled Investment Funds (000)

The $1,000,000,000 loan provides strong evidence of the sponsors’ ability to access credit markets on super-attractive terms. The lenders were a blue chip group of financial institutions and the terms—especially the possible deferral of cash interest payments—was quite attractive for Hertz. Such borrowing capacity does not seem achievable by almost any individual outside passive minority investor (OPMI) or group of OPMIs.

After extracting nearly $5 billion from Hertz and the public market, investment funds associated with CDR, Carlyle, and Merrill Lynch still owned about 26 percent of the outstanding common stock capitalization. At a price of 16.24 at the time of this writing, the market value of the Hertz shares held by the investment funds was over $1.8 billion.

We have not seen any of the private placement memorandums (PPMs) of the various investment funds. Therefore we do not know the terms of the relationships between the sponsors (i.e., general partners [GPs]), and the investors (i.e., limited partners or LPs or OPMIs). However, even assuming a high level of compensation to the GPs—say a 2 percent management fee plus a 20 percent profit carry plus all fees paid by Hertz going to the GP, Hertz seems to have been a super-attractive deal for the LPs. This super-attractiveness does not seem to trace to any achievements by Hertz as an operation in the last six and a half years. Rather it seems attributable to the talents evidenced by the GPs in accessing capital markets. This skill is not exclusive to CDR, Carlyle, or Merrill Lynch. We think it exists for among others, Brookfield Asset Management Private Partnerships, Vestar, and Leonard Green.

SPONSORS CONTROL OF HERTZ

The sponsors are in firm control of Hertz even though a majority of the Hertz board of directors have been “independent directors” since August 2011. CDR has two seats on the board, one of whom is chairman, and Carlyle and Merrill Lynch each have one seat. Directors now receive annual retainers of $210,000 of which $85,000 is paid in cash and $125,000 in equity. Additional cash compensation of $25,000 is paid to the chairman of the audit committee and other members of the audit committee receive $10,000. For service on the compensation, nomination and governance committee the chairman received $15,000 and other members $10,000. In addition after serving for 5 years, a director receives, among other things, free worldwide rentals for 15 years thereafter.

Other benefits accruing to the sponsors and investment funds include demand rights of registration for the sale of Hertz common stock and indemnification agreements. The reputation of the sponsors is probably a principal reason why Hertz common enjoys such a good aftermarket on the New York Stock Exchange most of the time despite the mediocre performance of the Hertz business since 2006. The really poor price performance of Hertz common occurred during the 2008–2009 economic meltdown. Otherwise Hertz common seems to be selling most of the time at very high P/E ratios and large premiums over book value. Table 25.5 summarizes the price history of Hertz common.

Table 25.5 Hertz Global Holdings Common Stock Price

| Year Ended 12/31 | High | Low |

| 2006 | $17.48 | $14.55 |

| 2007 | $27.20 | $14.81 |

| 2008 | $15.85 | $1.55 |

| 2009 | $12.55 | $1.97 |

| 2010 | $15.60 | $8.36 |

| 2011 | $17.64 | $7.80 |

| 2012 | $16.50 | $10.62 |

SPONSORS ATTUNED TO THE NEEDS OF BANKERS AND THE WALL STREET UNDERWRITING COMMUNITY

It seems to us that the sponsors are sensitive to the needs of bankers and the Wall Street underwriting community. In particular the gross spreads paid to underwriters seem reasonable, and as far as we know the sponsors try to price public offerings so that aftermarket prices will be buoyant, better than the underwriting price. This is in contrast with seemingly unsophisticated issuers, such as Facebook, Inc. who negotiated for minimum gross spreads and tried to price issues at peak prices while selling as many shares as is feasible in an IPO. A comparison of gross spreads is shown in Table 25.6.

Table 25.6 Underwriting Gross Spreads

| Issuer and Date | Gross Spread |

| Hertz 11/06 | 4.25% |

| Hertz 6/07 | 3.50% |

| Hertz 5/09 | 4.14% |

| Facebook 5/12 | 1.10% |

The aggregate size for the Facebook offering was far greater than any Hertz offering so that the aggregate dollars of gross spread for Facebook of some $176 million dwarfed the comparable number for Hertz. Yet it seems likely that Facebook was a lot less sensitive to the needs and desires of the underwriting community than were the Hertz Sponsors.

QUESTIONS ABOUT LBOS

Finally, there are three questions that arise in examining LBOs that follow the Hertz pattern, as we believe most of them do:

Given LBO sponsors’ predilection toward maximizing net present values for themselves and their LPs it would appear as if the LBO phenomenon contributes little, or nothing, to either growing a target company or making it more creditworthy. In fact, much of what the sponsors demand can be negative for the target company. This is sometimes ameliorated. When Hertz was in deep trouble in 2009, a capital infusion in the form of common stock by the investment funds and the public may have been crucial in having Hertz avoid a painful restructuring, perhaps in Chapter 11.

From a financial point of view it is hard to see how LBOs aid the economy. For starters it is axiomatic that having a target pay cash to departing stockholders, makes a target company less creditworthy than would otherwise be the case. Perhaps, if sponsors can make companies more efficient operations than they would otherwise be, a case for LBOs aiding the overall economy would exist. However, we have not seen evidence that LBO sponsors are particularly adept at improving operations. To date Hertz has been a mediocre operation. LBO sponsors can help target companies by giving them superior access to all capital markets—both credit markets and equity markets. However, with the focus on net present value; that is, getting cash out of the target, all too often sponsors preempt access to capital markets for themselves and their investors rather than for the target company. This seemed to have been the case for Hertz, except in 2009.

Given such super access to capital markets, there is no question in our minds that becoming a limited partner in investment funds run by CDR, Carlyle, or Merrill Lynch is an attractive option for OPMIs. The history of investor returns while the sponsors controlled Hertz is ample evidence of this. Because LBOs weaken credit worthiness ab initio and maybe during the life of the LBO ownership, the risks of a target company failure seem to be much above average. However, we think an OPMI would probably fare quite well could he, she or it become a limited partner financing, say, four or five Hertz-like transactions.

SUMMARY

Despite mediocre operating results subsequent to the LBO, the Hertz Global Holdings Transaction seems to have been quite remunerative for the LBO sponsors and their investors. In our view, this success is attributable mostly to the fact that time and again the sponsors enabled holders of Hertz Global Holdings common stock to obtain super-attractive access to capital markets. For example, sponsors and investors received two large dividends where the funds for paying one of the dividends came from a loan with liberal covenants, and for the other, from the proceeds of an underwritten common stock offering to the public. Sponsors have proven to be very skillful resource converters who appear to be very sensitive to the needs of bankers and the Wall Street underwriting community. We briefly discuss LBOs from the points of views of investors, the company and the economy.