Dad calmly walked back to the car and dropped the blood-streaked bat on the floor beside my feet.

A prison shrink once told me that by the time we’re seven years old, we are who we are for the rest of our lives, and there’s usually shit-all we can do about it. Our brains are hardwired forever, and it’s too late to change anything.

Too late to go from bad guy to good, or from sinner to saint—as Father Stanley might have said. Unlike the shrink, Father Stanley thought you could change your fate in the time span of one confession.

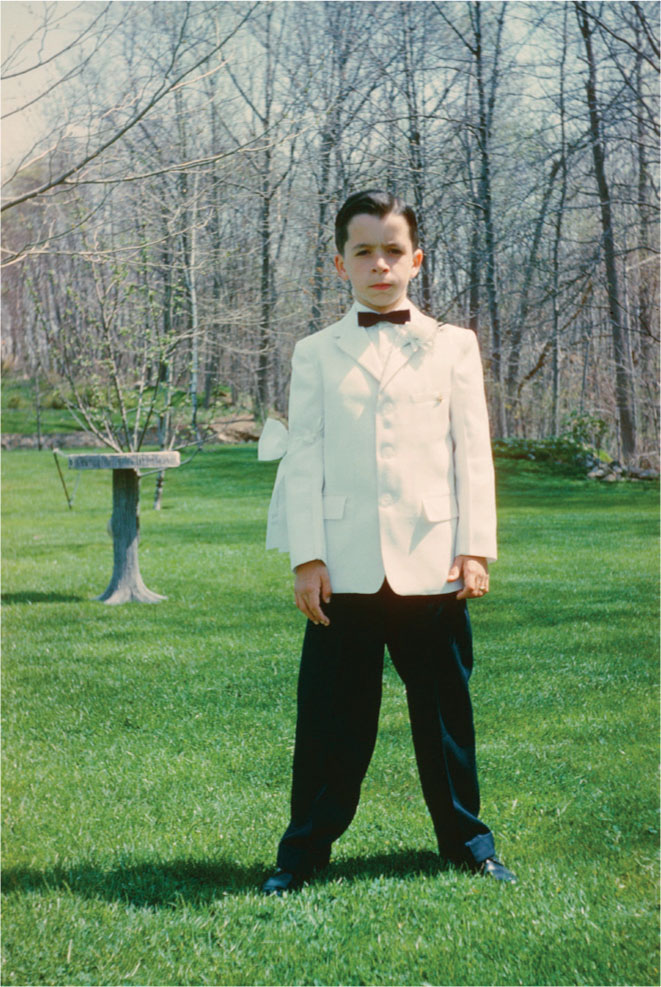

“You’ve reached the age of reason, Tommy,” he pronounced, solemnly, as I knelt in the jail-cell confines of the dreary confessional to make my very first confession, soon after my seventh birthday.

“From this day onward, you are morally responsible and accountable for all your actions. You have free will to choose your behavior.”

Well, I gotta be candid with you. If Father Stanley was delivering a message from his god, my parents and I never got the memo.

Because by 1960, the year I reached this age of so-called reason, my father had been beating the crap outta me for years and I was already an accomplished thief. So apparently the Giacomaros of North Haledon, New Jersey, didn’t do so good with this morally responsible accountability thing. Or ting. That’s how the guys I run with say it.

By my first communion I was already a crime boss.

My father, Joseph, went out bowling and card playing every Friday night. He’d return home stinking of booze and strange perfume, carrying a thick wad of bills he’d won gambling. Dad was an accountant; he was smart with numbers and knew how to get money outta people from right under their noses.

And so did I.

I’d be wide-awake when he staggered in at 4 AM—even as a kid, I slept only three to four hours a night, a habit that wore down my mother’s sanity—and listened closely as his footsteps echoed down the hall, into the den, then downstairs to the basement where he’d pass out asleep. He always slept in the basement on Friday nights so my mother wouldn’t wake up and know what time he got home.

I’d lie motionless under my blankets until I heard his floor-rumbling, boozy snoring through the floorboards directly below me.

And that’s when I’d rob the motherfucker.

Armed with a mini flashlight, I’d slip out of bed, move silently down the hall, and tiptoe into the den. I’d quietly slide a chair across the floor until it nudged against the bookcase—that’s where he stashed his wallet, on the top shelf. If I stood on the chair and stretched my arm as high as it could go and fished around, sooner or later my gloved fingers would bump into the thick leather lump. Yeah, I wore gloves when I slept—still do, but I’ll get to that later.

Hitting up dad’s wallet was like winning a lottery. It’s what we in the money-stealing business called “easy money”—the sweetest kind. It was always a sure bet. I’d peel four or five twenties from the bulging billfold and return it to the shelf. Back in my room, I’d hide the money in a hole I cut in my mattress.

Early Saturday morning I’d knock on Eddy LaSalle’s door to come out and spend the ill-gotten loot with me. Eddy’s dad had some important job as a business executive in Hoboken. In looks and personality, Eddy and I were exact opposites. I was dark, wiry, frenetic, and never shut up; Eddy was tall, shy, blond, and stocky. But we understood each other, Eddy and me. We both had trouble at home and there was shit-all either one of us could do about it.

But on Saturday mornings with my dad’s twenties burning a hole in my pocket, we hadn’t a care in the world. Back then Bazooka chewing gum cost a penny a piece, and I was a kid with a hundred bucks to blow. I was a fucking millionaire.

First we’d go to the Rendezvous, a nearby shopping emporium that sold girlie magazines and comic books, and stock up on Superman. Two doors down was Jay’s Luncheonette, where we’d hoist ourselves onto the counter stools and order deluxe cheeseburgers, French fries, and all the Coke we could stomach.

I loved the feeling of importance and power that the money gave me. Contrary to Father Stanley’s little morality lesson, I had no remorse about stealing from my father’s wallet. In fact, I was pretty confident that it was my moral responsibility to do so.

I ate fast, wolfing down the food like I was starving, and I was. But it wasn’t a physical hunger. I was feeding emptiness, stoking a burning anger, and numbing a pain inside of me with the stolen money and fast food. Every bite I took was a conscious fuck you to my father.

“This’ll show him,” I’d say, as we sat stuffing our faces. Eddy would shove ketchup-drenched fries in his mouth and nod. He knew exactly what I meant.

I was five years old when I first saw my father’s fierce Sicilian temper. We were driving home from a relative’s house on a beautiful spring afternoon. My mother, Yolanda (“Lonnie”), was in the passenger seat and I was sitting in back reading a comic book. Even my father seemed in a rare good mood—that is, until the driver next to us swerved in front and cut him off. That driver obviously didn’t know my father was the last person in the world you want to fuck with, and until that day, neither did I.

Joseph Thomas Giacomaro had been a technical sergeant in the US Marine Corps and had seen combat in both World War II and Korea. At a lean 5′8″, he was neither tall nor beefy, but that didn’t matter when you were a trained expert in hand-to-hand combat.

He returned from Korea after being discharged in 1954 with a trunk load of combat memorabilia: his banged-up canteen; a utility belt with a leather holster for a sidearm; two standard-issue field blankets; his camo-green Marine Corps jacket (which he wore once a week when he mowed the lawn); and his prize possession, a menacing, black-handle bayonet with a ten-inch blade. He kept the bayonet locked up in a closet and once, just once, he demonstrated how it was used.

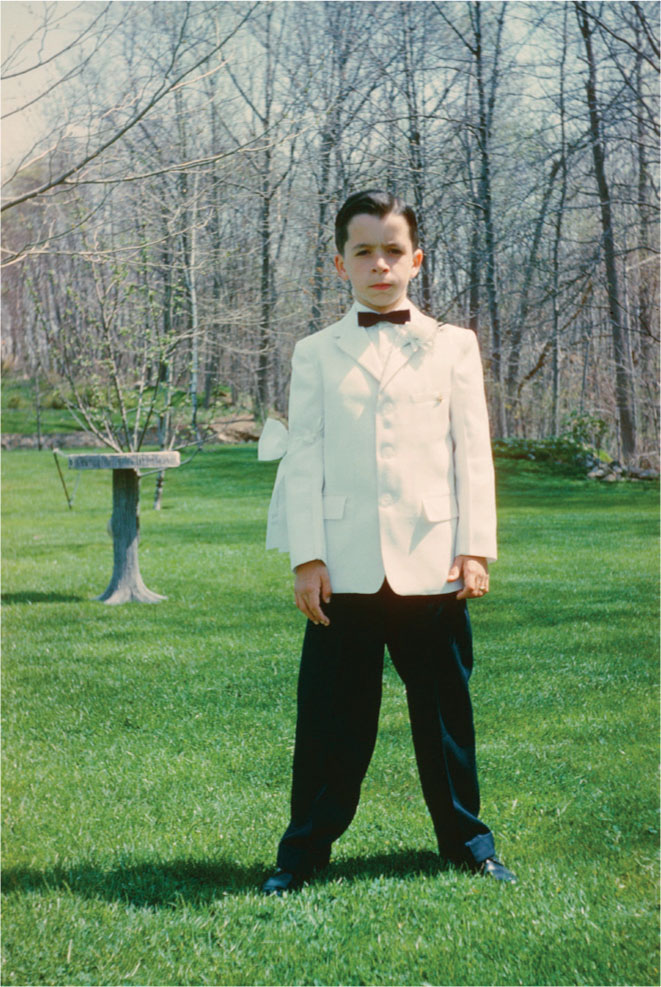

My father in his US Marine Corps uniform

My mother and I were in the kitchen, and she was showing me how to make tomato sauce. From an early age, she taught me how to cook and sew.

“You never know when it’s going to come in handy,” she used to say, as I stood on a chair and stirred the bubbling sauce. That’s when my father came into the kitchen with his bayonet and drew the blade out of its fiberglass scabbard. Suddenly, cooking wasn’t so interesting to me anymore.

“Did you use that to hit people?” I asked, hopping down from the chair.

“Hit people? ” he scoffed. “You don’t hit someone with a bayonet—you jab them, you poke them,” he said, gripping the weapon tightly in his hand. He lunged across the linoleum and thrust his arm out in front of him. My mother and I both jumped back.

“You jab your enemy in the guts and then twist the blade to cut him up inside. One less enemy to worry about,” Dad said to himself, smiling.

Like I said, Dad wasn’t big, but he could fight. And anyone who knew him will tell you he had a certain lunacy in his corner—when he got worked up, he was a fucking madman.

On the road that day, Dad blared his horn at the other driver and screamed out the car window: “Pull over, you motherfucker!” A couple of minutes later, we caught up to the car at a red light and two huge, very angry-looking black guys climbed out and started walking toward our car.

Before they had a chance to say or do anything, my father had grabbed the Louisville Slugger he kept under the back seat and was on top of them.

“Joe, nooooo!!! ” my mother screamed.

My father didn’t swing the bat, he lunged and poked and jabbed the two men all over their bodies—in their stomachs, their chests, their faces, and then the back of their heads after they crumpled to the ground, begging him to stop.

“Fuckin’ nigger motherfuckers,” he hissed, as he kept on jabbing them as hard as he could. The fact that they were black made their beating twice as brutal as it might have been; my father was a racist son of a bitch.

I watched through the car window, trembling, as my mother sobbed. When Dad first jumped out of the car, I was worried he’d get hurt in the unevenly matched fight. Back then, he was still a hero to me. I proudly wore his Marine Corps jacket and belt when Eddy and I played army in the woods.

But it was those towering black guys who didn’t stand a chance. When my father was done with them—it was over in a couple of minutes—they lay in the street, curled up and still, as a frightened and confused crowd began to gather. Dad calmly walked back to the car and dropped the blood-streaked bat on the floor beside my feet.

“Two less enemies,” he muttered.

He got behind the wheel and sped away. The only sound in the car the rest of the way home was my mother’s whimpering. I have no idea if those two men lived or died.

![]()

A few months later Dad started beating the shit out of me, too.

For reasons I didn’t know or understand, he’d snap—he’d fly into a sudden rage and chase me all over the house until he cornered me, usually in the dining room.

“You’re no fucking good!” he’d shout, as he hit me hard with his open hand. I’d yell for my mother to help, but what could she do? How do you stop a maniac?

“Not the head, Joe, don’t hit him in the head! Not the face!” was all she could offer. She was afraid I’d get brain damage, or that everyone in church would see my bruises. Back then, it was normal to take a swipe at your kid, and it wasn’t anyone else’s business. But even for that era, she knew what he did to me was too much.

I’d crumple to the floor just like those guys in the street, and then he’d spit out the words to me that he’d repeat for the next forty years:

“You will never, ever, amount to anything,” he’d say, looking down at me. He looked like a monster. “You. Are. Nothing! ”

When it was over, I’d run across the backyard to hide in the woods behind our house and sit on a rock and cry. I’d stay there for hours, embarrassed to go to school or play with Eddy because everyone would see the purple blotches spreading across my arms—defense wounds.

Please, god . . . make my father stop hitting me. Please help me, god.

From my rock, I’d hear him go after her. My mother was so bony, thin, and frail; her screams would travel through our open windows, rise up in the woods to reach me, then fall silent.

The next morning she’d wear a scarf to try and hide the welted handprints around her throat.

“Please, don’t call Uncle,” I’d beg her. My mother’s truck-driving brother, Anthony Foglia, was a Teamster and built like a brick shithouse. He was the only one I knew who had the balls and strength to kill my father if he wanted to. But despite the beatings my father gave us, I couldn’t stand the idea of him getting hurt. So whenever I could, I’d get in between his hands and my mother’s throat, even though that bit of heroics always cost me a second pounding.

I assume it was my father’s abuse that drove Mom to drink, just like it drove me to steal. She’d start on her wine at 5 PM—“the bewitching hour,” my father called it—in anticipation of his arrival home from work at 6 PM. As soon as he walked through the door, he’d pour himself the first of many vodka martinis or straight-up scotches of the night. But he’d hit me whether he was sober or drunk; that didn’t make a difference.

My beatings continued—two or three times a week—until I was sixteen. My mother wasn’t so lucky. Her sentence went another forty years, until my father died.

And that’s why, Father Stanley, I chose to steal my father’s money when I was seven. That’s why it was reasonable for me to take revenge on him with my small act of petty larceny without feeling the least bit guilty.

That’s when getting back at my father started.

I’m not sure it ever ended.