The less I reacted, the harder he hit; but nothing he did could make me even flinch. And I refused to stay down.

I was born on January 30, 1953, in Paterson, New Jersey, and grew up in the leafy, upper-class suburb of North Haledon. My parents were also born in Jersey and so was one grandparent, while the other three stepped off the boat from Sicily.

When I was a baby, my mother used to tie my hands to the high chair while she fed me so I wouldn’t make a mess—in handcuffs at six months! As soon as I could walk, she tied me to the backyard clothesline with a ten-foot rope so I wouldn’t escape the confines of our yard.

I was so hyperactive that I barely slept, and I got worse depending on the lunar calendar.

“You’re possessed!” my mother used to say, “and it’s worse during a full moon.”

I couldn’t figure out if I was born bad, like my father insisted, or if I became that way. Did he hit me because I was bad, or did I act out because he hit me? This I would try to figure out as I sat on the rock in the woods. More than a few shrinks tried to pick my brain to untangle the mess in there, too. I do know that around the time my father began beating me, I started getting into trouble.

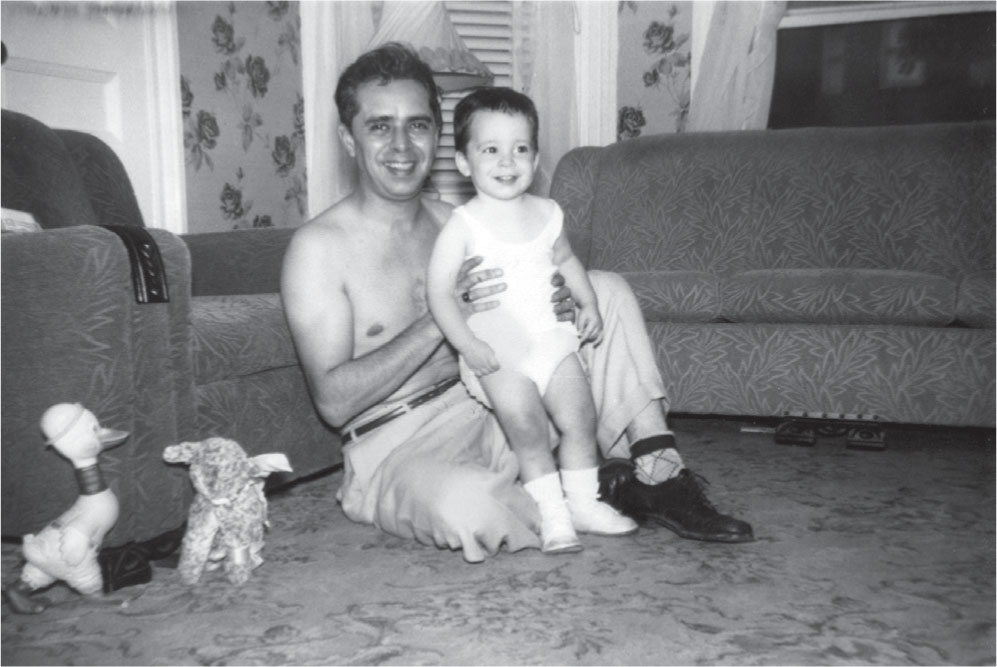

With my father, before the hitting started

In kindergarten at St. Paul’s elementary school, I refused to nap like the other kids or stand and put my hand on my heart to pledge allegiance to the flag—not because I didn’t love my country, but because I couldn’t stand being told what to do. I also couldn’t sit or stand still, never mind sleep in the middle of the day. No one talked about attention deficit disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder back then so instead of getting help from a school counselor or being pumped full of Ritalin, as they do today, I was simply labeled A Bad Kid.

Sister Ann patrolled the rows of desks like a gestapo officer. She was in her eighties and wore a heavy black habit and a starched-white cornette that projected from her head like Satan’s horns. During her rounds, she often found good reason to stop at my desk and yank my hair or jab my head with her ruler—her version of the bayonet. It wasn’t the pain that bothered me—I got it way worse at home. It was the humiliation I felt in front of my classmates when I’d put my head down on my desk and sob. A bunch of those kids bullied me for years.

When one ferocious ruler attack left a gash across my ear, my father saw it and recognized it wasn’t his own work. He marched into the rectory, dragging me with him, to confront Father Stanley—it was one of the few, perhaps only, times he ever stood up for me. Apparently it was okay for him to beat his kid until he was black and blue, but goddammit there was no way in hell anyone else could lay a hand on me.

“You and your people,” he said to the priest, “keep your fucking hands off my fucking kid.” My father was not a religious man and he harbored no reverence for nuns and priests.

![]()

My parents moved me to a public school with no ruler-wielding nuns—Memorial School in North Haledon—but I got in trouble there, too. Pranks like putting tacks on kids’ seats or shooting spitballs made me a regular in the principal’s office.

“What did you do this time, Thomas?” the principal would ask.

“I didn’t do it!”

“What didn’t you do?”

“I dunno. Whatever it was, it wasn’t me!”

I was excellent at convincing him there’d been a misunderstanding, or that I was the innocent victim of some other kid’s scheme of the day. As I convinced him, I convinced myself, too. Yeah, yeah, that’s what happened. It’s the truth! Or maybe the principal was a soft touch because he’d seen the bruises peeking out from under my shirtsleeves. Whatever the reason, he felt sorry for me and I played to his sympathy.

“The teacher picks on me,” I’d say, eyes downcast.

“Okay, Tommy. You can stay in the office for the rest of the day. Go sit in the corner.”

Only I couldn’t sit still there either. So I ran errands and organized files for the secretaries, who hugged me and fed me cookies. I learned an important lesson by being sent to the principal’s office: that my bad behavior would be richly rewarded. Hanging out with the secretaries was a vacation next to the rigid structure at home, where my parents—both undiagnosed obsessive-compulsives—ran our house like a military boot camp.

After my father was honorably discharged from the Marines, he began working full-time as an accountant for a highfalutin firm in Clifton. He was so smart, number savvy, and precise that he could make any ledger line up like the blades of grass along the edge of our driveway. He’d lie down on the front lawn in the evenings and clip each individual blade of grass by hand to make sure their heights were uniform. His own father was like that, too. Grandpa Sal owned a barbershop in Paterson and he’d trim each hair on people’s heads until it was just so—one strand at a time. (My mother’s father had a barbershop, too. Later on, I learned that one of them was a front for a numbers racket.)

At night, my father was in high demand to balance the books for local mob-owned restaurants and meat and produce markets. They knew he’d keep his mouth shut about the money they pulled in off the books, and with the extra cash he could buy his Cadillacs and Oldsmobiles. He used to hand-wash his four-door, white 1958 Oldsmobile, a real mob car, in the driveway, and I was not allowed to touch it or play in it.

My mother was an old-fashioned Italian mom, devoutly Catholic, and a germaphobe who kept every stick of furniture in our home hermetically sealed in industrial-strength plastic, as though humans didn’t live in our house. If she could have boiled the living room couch in rubbing alcohol to sterilize it, she would have. She painstakingly dusted her Hammond M3 organ in the living room every day using a special yellow cloth, then waxed it with canned butcher’s wax.

I don’t know how they found each other. Together, my parents made the world’s most anal-retentive couple, and I was their dysfunctional protégé and whipping boy.

My parents on their wedding day

My mother ordered me to wash my hands every hour with Lava soap—the kind used by coal miners, oil-rig workers, and auto mechanics. It burned and ripped the skin off my hands so badly that at night she’d slather them with Vaseline and give me cotton gloves to wear as I slept. Those gloves summed up my life: I lived in a home I couldn’t touch, with people who didn’t touch me (except in the wrong ways). Even at night when I acted the stealthy cat burglar, ripping off my father’s money, I left no fingerprints behind.

I slept beneath Dad’s Marine-issued blankets—they were woolen and itchy but warm as hell. He taught me how to fold them and make my bed like a proper Marine.

“Hospital bed corners, like we do in the corps!” he’d say at inspection time every morning, and toss a coin onto the bed to make sure it bounced.

Each room in the house had to be organized to my parents’ exact specifications—the canned goods in the kitchen were lined up by height with labels facing forward. Ever see the movie Sleeping with the Enemy? That was my father. The socks in my drawers were lined up by color and the rows couldn’t touch each other. Even my toy soldiers had to be put away in proper formation, standing at attention and at the ready.

It was a sickness: my parents desperately needed order; there was no room in their lives for chaos. My misbehaving, that was a mess. Affection or hugging, that was messy. Even at five years old, I could see that other families weren’t like mine. I watched Leave It to Beaver and My Three Sons on our black-and-white TV and saw how they talked nice at dinner, and how June and Ward asked Wally and Beaver about their day. Sometimes, I’d pretend to be like those TV families. I’d hold my mother’s hand mirror up to my face and kiss my reflection.

I love you, Tommy, I’d say to myself.

There was something else that happened when I was age six or seven that wasn’t quite right. It was a potential mess that had to be hidden away, and even though I have a photographic memory about everything else in my life, this I remember in a blur of images.

For six months or so, my mother went away. I didn’t know why, but I remember my father signing papers and my mother leaving in an ambulance. I remember him taking me to visit her on Sundays in a big gray building, surrounded by people wearing white coats. She’d beg to come home but my father would shake his head. During those months, Dad took me to his sister’s house, Aunt Millie’s, instead of school. I played with my cousin, Anthony Bianco. We were the same age, but he was a nerdy, smart bookworm with thick glasses. Aunt Millie would take us to the Jersey Shore and we’d run up and down the beach all day long. Then one day, Uncle Anthony went and signed papers and my mother came home.

If it wasn’t for Charlie and Midge next door, I’d have turned out crazier than I did. Or I’d be dead. The Gerhardts were our neighbors from the day we moved into the house in North Haledon. They didn’t have kids of their own. Charlie owned a sporting goods store in Paterson, and Midge worked for New Jersey Bell Telephone. They were my parents’ best friends and to me, they provided my first “safe house.” If I knew they were home, I’d run to them instead of the rock after my father’s beatings. I’d get into their house through the back door, which they left unlocked for me, and stand in the middle of their kitchen, silent.

“Tommy . . .” Midge would say, pulling me into a hug. She knew.

Charlie would come over to me and put his hand on my shoulder, shake his head, and mumble something under his breath.

After hamburgers and fries with Eddy on Saturdays, I’d go to the Gerhardts’ for hours and play with their kitchen gadgets and make a mess in the sink. Charlie let me drive his red 1957 Chevy up and down his driveway with the radio blasting. He was a kind, soft-spoken, easy-going man. He brought me baseball gloves and footballs from his store and signed me up for Little League when I was nine years old and took me to all the practices. He tried to make things better between my father and me, but it never worked.

On the night of my first Little League game, Charlie convinced my father to attend with him to surprise me. I’m sure it took a few vodka martinis. When I got to bat, I scanned the bleachers and saw Charlie’s smiling, encouraging face . . . and my father’s scowl next to him.

Holy shit.

I kicked the dirt and got into position. This was my chance to make my father proud, to show him I could be something, that I wasn’t nothing. But the first pitch was so fast and far inside, it hit my left shoulder and knocked me off my feet. And just like in kindergarten, I burst into tears. The coach led me back to the bench to put ice on my shoulder, and I caught sight of my father’s face on the way: pure disgust. Nothing Tommy had struck out and I stayed benched for the rest of the game. Charlie tried to console me in the car as we drove home, but my father wouldn’t even look me in the eye.

I never played baseball—or any sport—ever again. And after that day on the field I never cried again, either—not for another forty years.

![]()

At home, I found small pockets of happiness. Sunday was a special day regardless of what violence had taken place in our home during the week. I seldom got hit on Sundays. My mother cooked roast beef or leg of lamb, and my father let me watch the New York Giants with him if I kept quiet and out of his way. We also played chess; my father learned it in the Marine Corps barracks and was so desperate for an opponent that he taught me how to play. I took to it immediately, maneuvering the men on the chessboard, knowing instinctively how to see the best moves several plays ahead and win the game, which infuriated my father.

When I was alone, I imagined escaping my world. I was obsessed with The Wizard of Oz and wished that I, too, could go to a fantasyland far away.

Every year after the Labor Day weekend, I’d start counting down the days to Christmas. I’d take out my Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, and Dean Martin Christmas tapes, which I’d recorded off the transistor radio, and play them while pretending to do homework. Schoolwork bored me, but Christmas music made me feel happy—it sounded hopeful. And even though I still got beaten at Christmas, my mother would decorate her dining room mahogany furniture with cotton so it looked like snow—so at least I got beaten with a festive background. Starting in early September, I played the crackling tapes over and over:

Jingle bells, jingle bells, jingle all the way . . .

My father would bang on my bedroom door.

“It’s September, dammit! Stop playing those goddamn Christmas carols!” Whatever attention I lacked from my parents in some areas, they overcompensated in others. (Overcompensated—a useful word I learned later in prison therapy.) I was the best-dressed kid in school—wearing green-and-blue silk Nicky Newark guinea chinos, leather shoes, and Italian knit shirts when other kids wore junky dungarees and turtlenecks. And up until I was ten, my mother insisted on tying my shoes for me. After school, she’d be waiting to drive me home at 3 PM.

“Overpossessive” was another term I heard later in therapy. My mother literally—and I do mean literally—wiped my ass for me right up until my tenth birthday. I’d call her from the bathroom after I was done pooping.

“Ma, I’m done!” A few seconds later she’d be running up the stairs with a warm, wet towel in her hand to finish the job.

“Bend over,” she’d say.

Meticulous. Germaphobe. Obsessive. And more than a little anal-retentive, that was my mom. She even flushed for me. Why did I let her do this? I knew it was warped, but it was as close to physical affection and love that I got. Freud woulda had a field day with that one, a fucking wet dream.

I went to my first psychiatrist around the age of eight. My parents were worried because my acting out in school was getting worse and my marks were plummeting. They really had no idea what could possibly be troubling me. Neither, it seems, did the headshrinker.

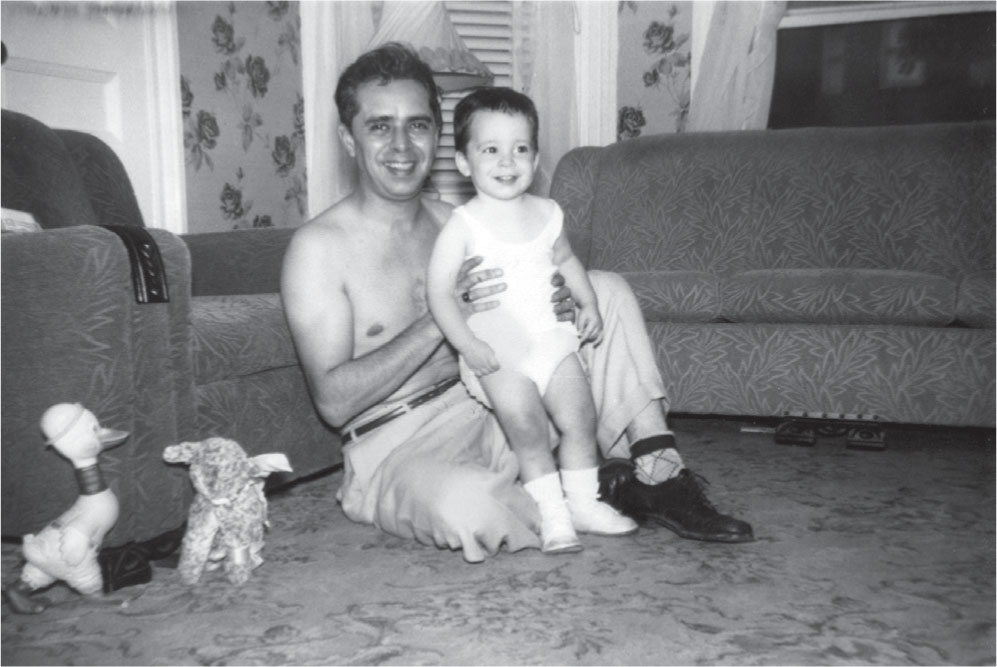

In the backyard playing with the sheath of my dad’s bayonet

My mother waited in the Cadillac as I sat in his mildewy office twice a month for four months, answering the same questions each visit.

“How are you feeling, Tommy?”

“I’m all right.”

“How are things at home?”

I stared at the heavy, dusty drapes on the window. No wonder my mother wouldn’t come in.

“Like I said, my father beats me.”

After which he’d talk to my parents, and they’d explain I got spanked for misbehaving, and all three would unanimously agree that I was A Bad Kid. My father now had official confirmation from a professional of the diagnosis he’d reached on his own years before!

The doctor gave me a multiple-choice IQ test to determine if I was dumb as well as bad. But as it turned out, I was very, very not dumb. The first time I took the test I scored 159; he looked at the results and said, “This can’t be right.” I took the test again and scored even higher—189—which landed me somewhere between “very superior” and “genius.” The doctor looked baffled but didn’t ask me to take it a third time. I don’t know if he told my parents about the scores, but if he did, they said nothing to me.

Needless to say, my first shrink wasn’t any help, and by the time I reached age ten, my stealing had gotten worse—or better, depending on your point of view. Already the little businessman, I decided to expand beyond the regular looting of my dad’s wallet and diversify. Every good thief knows the importance of a diversified portfolio.

Behind our house and beyond the woods, a row of split-level homes was under construction on a vacant strip of land, and the unguarded site was like catnip to my stirring criminal sensibilities. I knew there had to be something there I could steal and sell, but this wasn’t a solo job; I needed backup. I recruited my first crew—my best pal, Eddy, Mikey “The Bike” Tossellini (whom I met in catechism class), and Danny Gravano (whose father, we were told, was a cement truck driver).

I drew up the plans for our first job—we’d break into the unfinished homes and steal cases of lightbulbs, nails, plumbing supplies, and toilet bowls, and resell them to hardware stores in town at a ridiculously discounted price they couldn’t refuse. Even earning pennies on the dollar—like ten bucks for a $100 toilet—I made a small fortune. And the thrill of pulling off my organized crime gave me a total adrenaline rush.

Like with Dad’s wallet, I didn’t feel a trace of guilt or remorse over it. But since my mother made me go to confession every Saturday, I did tell Father Stanley about it. He wanted me to be accountable, after all, so I gave him a full accounting. I’d been an altar boy since I was seven and went to church with my mother on Sundays. But I had doubts about this god she worshipped. After five years of praying to him to stop my father from beating my mother and me, the beatings had gotten worse. I didn’t feel this god looking after me at all. The year I turned ten was also the year President John Kennedy was assassinated. The entire country was sobbing in the streets, and it made no sense: If this god was all-powerful, all-loving, and all-knowing, why would he let such a tragedy happen? Fuck mysterious ways. Maybe I wasn’t important enough to watch over, but President Kennedy was.

My mother, on the other hand, was certain someone or something was protecting me. She started believing this after I got into a bike accident at age six that should have killed me. I went flying down the driveway and flipped over the handlebars, slamming my head into the cement sidewalk so hard I got a major concussion and my mangled teeth were pushed up into my nose. I was rushed to the hospital and into intensive care . . . but the next day when I woke up, “It was a miracle,” my mother would say, looking heavenward, when she retold the story over the years.

“The doctors and nurses were in shock to see that he’d completely healed! You’re special, Tommy,” she told me after that. “You have a gift that saves you from trouble.”

Maybe so, but Father Stanley wasn’t buying it. He told me I was a sinner, so I lined up with a hundred other kids at the confessional. Inside, I’d start with the smaller sins and work my way up.

“I was disobedient in school,” I’d say, peering into the latticed grid. “I talked back to my mother. And me and the other altar boys drank wine from the chalice . . .”

I had inherited my parents’ genetic propensity for booze. Eddy, Danny, and I used to get into my father’s bar in the basement and mix gin, vodka, and scotch into Coca-Cola bottles and get drunk in the woods. We also siphoned off homemade wine from the barrels in the Gravanos’s garage. Getting drunk was another good way to escape my abusive world, I found.

“And, oh yeah, Father”—I’d save it for last—“I broke into a bunch of empty houses and stole everything that wasn’t nailed down.”

He yawned.

“Say twenty-five Hail Marys,” he’d say, “twenty-five Acts of Contrition, and twenty-five Our Fathers. Ego te absolvo, I absolve you from your sins. In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

I was in and out in less than a minute; he had a big line to get through before lunch. By twelve, when puberty struck, I refused to go to church anymore. If there was a god, he clearly didn’t give two shits about me.

Eddy and I had graduated from plastic toy guns and comic books to BB guns and Playboy. And something else had changed inside of me that I couldn’t articulate, but I knew instinctually: I was losing the ability to feel fear or pain.

My father had been beating me up and telling me I was no good for more than half my life, and now I felt something inside of me cross over. A decision had been made; a wall had gone up. If no one could stop my father from hitting me, then I’d stop him from hurting me. How? I would refuse to feel the pain.

The next time Technical Sergeant Joseph Giacomaro lunged toward me in the dining room for hand-to-hand combat, I didn’t put my hands up to block his blows.

“Go ahead,” I said, “beat me as much as you want.” My voice was so cold and far away, I barely recognized it.

My father hit me, again and again, until I fell to the floor. I got up.

“Is that it?” I said, smiling at him. “Give me some more.”

So he did—he kept pounding on me until my mother screamed so loud, I’m sure they heard her down at the Rendezvous. Blood and spit flew from my mouth. The less I reacted, the harder he hit; but nothing he did could make me even flinch. And I refused to stay down.

Even when he threw me against the wall and I slid to the floor, I got up and laughed in his face.

“Is that all you got?”

My mother begged me to be quiet and begged my father to stop—but neither of us did.

He was out of his mind. And I felt nothing.