We were more than a fraternity; we were a mini-mob.

Sometime after my sixteenth birthday, I snapped.

My dad came at me with his hand raised and his face twisted, and I fought back. I didn’t hit him, no. My Sicilian blood prevented me from decking my own father; it was too disrespectful. And a small part of me still clung to my childhood image of him as my hero—I wasn’t ready to completely kill that. Besides, the son of a bitch was two inches taller than me and a trained killer.

But what I lacked in height and training, I made up for with anger. I had learned rage from him, but I was smarter than he was. I knew where to attack to cut him the deepest without laying a finger on him: his perfectly ordered world. I was going to wreck his house.

He had me cornered in the dining room again. As he geared up to swing, I picked up a chair and hurled it across the room, aiming for my mother’s beloved Hammond M3 organ and hitting it.

“C’mon Dad, let’s go!” I yelled. He stared at the organ in horror, then at me, shocked. His arm was frozen in the air.

“You want to hit me all the time? You know how many times you’ve hit me, you motherfucker? Fucking hit this.”

I moved to the organ, picked up the bench, and smashed it against the carefully polished cherrywood—gouging the top panel and music stand and breaking a bench leg. My mother rushed into the room and screamed.

“You ruined the bench!”

“Yeah, fuck you, Ma. You love your furniture more than you love your son. I took beatings all my life. Now your organ is taking one, what do you think of that?” I reached for another dining room chair. “How about I start breaking everything in the fucking house?”

Their faces were as white as a New Jersey blizzard in February. I looked at my father: “You beat me one more time, and I’ll destroy this place. You wanna see crazy? I’ll show you who’s fucking crazy.”

My father put his arm down and my parents backed away. It was the last time he ever raised his hand to me.

I taught my parents a lesson that day, oh yeah; now I was the one not to fuck with. The following week the furniture repairman fixed the leg on the organ bench, but the deeply etched grooves and scratches on the wood would remain forever—an everyday reminder to us of the time I staged my coup and seized power in the house.

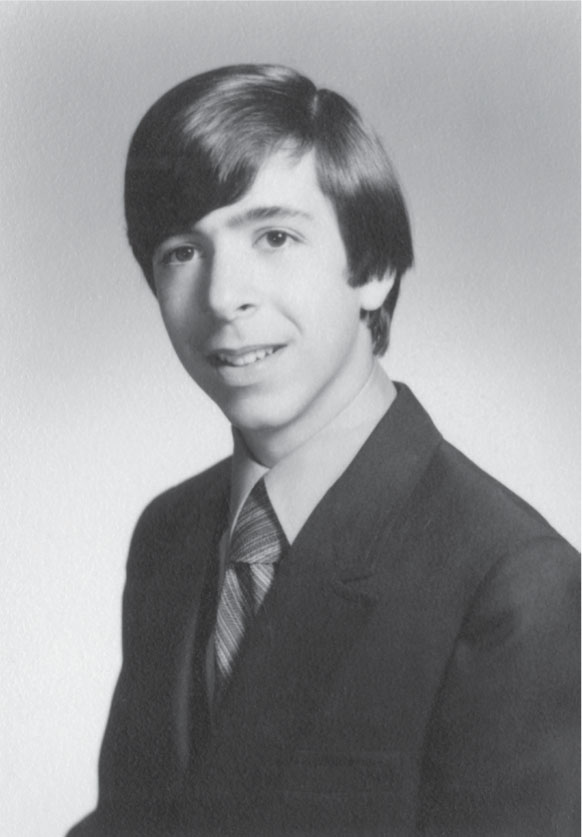

My high school yearbook photo, just before I took over the school

I took that new attitude with me to Manchester Regional High, and in my junior year became boss there, too.

In the late sixties and early seventies, high school fraternities in Jersey were basically gangs who tortured and beat up each other. We had Kappa Gamma Lambda (KGL), Omega Gamma Delta (OGD), and Alpha Beta Sigma (ABS)—they were all mostly jocks—and Sigma Kappa Delta (SKD), who were street thugs.

Hell nights were brutal. SKD called their pledges “dogs” and KGL called theirs “moose.” They stripped the guys in the woods (where no one could hear them scream) and gave them seventy whacks with a wooden paddle until they were bruised from ass to thighs. Assuming the pledges survived that, they then had their balls smothered in chili sauce and deep heat until the skin fell off. Lastly, the frat would pelt the pledges’ heads with eggs until their skulls pounded. This went on for eight to twelve weeks.

“Fuck that,” I said to Eddy and Danny and my new buddy, Billy Stone. I wanted the power of being in a gang, but on my terms.

“We’re going to start our own fraternity,” I announced. “And we’re going to get big. And it’s going to be the most powerful one of all.”

That’s how I talked now, in blustering hyperbole. I had the idea for ten seconds and was already plotting expansions and takeovers. I dubbed us Gamma Sigma Delta and ordered sweatshirts and sweaters in navy and gold to wear under our leather jackets.

I began with a crew of twelve—like a bunch of badass apostles and their false messiah. I was the president, treasurer, boss, and brains of the outfit. We didn’t stay twelve for long because I had a talent for luring, organizing, and convincing others to join and do what I wanted. I moved people around like pawns on a chessboard, like when I played with my father—thinking a few steps ahead of the game with the grand plan to win, be the biggest, be the most powerful.

Our first stop to recruit new frat members was the toughest high school in South Jersey—Paterson Tech. That’s where the biggest, meanest black guys went, and no fraternity had dared recruit there before. To me, they were fresh meat, potential marks, and an untapped market. Eddy and I hopped into my secondhand, light-blue metallic 1965 Chevy Impala and crashed their after-school dance the following Friday. We intended to leave that crepe-papered gym a few hours later with either broken noses, new frat brothers, or their women . . . or all the above.

I arrived with Eddy, my official bodyguard, at my side. At seventeen he was now 6′2″ and a lean, mean basketball star at Eastern Christian High School. Like me, he also had a screw loose in his brain and a rage from his own father beating him. Eddy could turn into a lunatic in one second if provoked, ideal bodyguard material. As soon as we got on the dance floor, a circle of big black guys surrounded us.

“Who are you?” the biggest one asked me.

“We’re Gamma Sigma Delta, that’s who we are,” I said. “And we want to bring you into our fraternity. I’ll give you your own chapter. You’ll make a lot of money. And all the girls will want you. And you,” I said to the biggest one, “you’re going to be president of your chapter.”

I was no dummy and neither were they. They wanted power, too, and they knew it came in numbers. I also knew these guys sold drugs, and they were at that moment tabulating in their minds how many new customers they’d inherit by joining a fraternity.

I needed them and they needed something from me. And that, in a nutshell, is the art of the deal. I sweetened the pot by describing the girls, the money, and the cool sweaters, and in one hour I’d added forty of the toughest guys within a fifty-mile radius to our gang.

The following Friday we crashed a dance at Paterson Catholic, where I had an even bigger deal in mind.

Kappa Gamma Lambda had been around since the fifties and had the most jocks—it was new compared to the older frats OGD (established in the early 1900s) and SKD (established in the 1920s). I knew KGL guys would be at the dance, so when we got there, I zeroed in on one of their members, Stevie Moretti, and gave him my pitch. Stevie’s job was to bring in new members, but what I suggested was heretical.

“I want a merger,” I told him. “You need us delinquents for your fights with those SKD street thugs.” Stevie nodded, and said he’d take me to his leader.

A few weeks later I was standing in front of KGL’s grand president, Dennis Greenwood, in his parents’ basement in Hawthorne. That’s where frats often held meetings—in their mommy and daddy’s finished basements, complete with wet bar, dartboard, and an original edition of Twister, circa 1966.

Dennis was a blond, WASPy-looking kid headed for prep school, no doubt, and the whole damn football team surrounded him that night. Next to them, Billy, Danny, Eddy, and I looked like a bunch of long-haired hoodlums in leather jackets, bandanas, and knives hidden in our boots.

“How many guys you got?” Dennis asked. We had fifty-three.

“We got a hundred guys,” I lied. The falsehood slid off my tongue effortlessly, like butter sizzling across a hot skillet. It came so naturally, I didn’t see it as lying at all: I was telling the truth as it could and would be. Alternative facts, you might call it. I could get another fifty guys no problem so in my mind it was already done.

“We want to merge with you,” I continued, “but we’re not doing no regular hell night or taking seventy shots on the ass and getting messed up. You want us? My top three guys here and me will do three shots each to show our loyalty and that’s it. We’ll give the KGL oath to the rest of our guys.”

Dennis eyed the knives in our boots and agreed to my terms. Right there in the basement, they whacked our asses with wooden paddles they’d made in woodshop class. They were two inches thick, twenty-four inches long, twelve inches wide, and the shape of a pizza paddleboard. You had to use oak or maple so the paddle wouldn’t snap when you hit a guy hard.

That night, we traded in our navy and gold colors for green and white—we were officially a chapter of KGL with me retaining my titles of president and treasurer.

Over the next several weeks, I continued my plans for expansion. I made the rounds of high schools in the nefarious regions of town with my crew—crashing dances and luring in the toughest fighters with promises of money, girls, power, and no hell night humiliation. It was good training for the mergers and acquisitions I’d do later as a salesman.

We drove from school to school in my Chevy, but I never paid for gas. I’d back my car into the driveway of someone’s highfalutin mansion late at night and send Danny out to stick a hose into their gas tank and drain it. We kept a hose in my trunk, buried under stinking sports equipment and shit-stained underwear—another one of my early, brilliant ideas. I got Stevie to put real skid marks on a bunch of ratty underwear, and we laid them across the junk in the trunk in case a cop stopped us and took a look. The entire trunk smelled like dirty ass. One glimpse and sniff of the shit-stained skivvies and the search was over.

In two months, I added one hundred more members to KGL and had big plans for how I’d play my new pawns.

One of my after-school jobs was working the cash register at the local A&P—then called The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company. Once I saw that the assistant manager on night duty was either drunk or asleep in his office, I organized my chess pieces.

During my shift, a bunch of guys would come in and load up shopping carts with steaks, chops, ribs—hundreds of dollars of meat, expensive produce, and imported tinned specialty items.

Ka-ching! I’d punch in a few items and let them by with the rest for free.

Meanwhile, I organized a whole other operation in back. Four of my guys would pull up at the delivery door in their hippie van and we’d load it up with boxes of meat out of the freezer and storage fridge. The next day we sold it to local markets, and what we didn’t sell, we’d cook and eat at our frat house and wash it down with Rheingold Beer.

We found a run-down house in Paterson and rented it for $150 a month, furnishing it with used sofas, mattresses, and a stolen jukebox. It was a top-secret man cave—no girls allowed, not even for fooling around. That’s what cars were for. Stevie and I picked up girls and made out with them in my Chevy until the cops banged on the steamed-up windows. One girl I had my eye on was the gorgeous captain of the cheerleading squad, Angela DeAngelis, who was older than me and didn’t give me the time of day until after we’d both graduated. We smoked hash, had sex, and she dragged me to radical political meetings. She urged me to rob banks with her—“not for the money,” you understand, but “as an antisocial statement.” After I lost touch with her for a year or so, I saw her face in the newspaper: she’d become a founding member of the Symbionese Liberation Army, the American terrorist group that kidnapped Patty Hearst in 1974. In May of that year, she was killed at the SLA’s safe house during a shootout with police that was broadcast live on television.

With my A&P operation, the money was rolling in. After the first month the inventory was short $43,000 and the shocked manager thought it must be a mathematical error. The second month we were short $67,000. In month three, the general manager of all the New Jersey Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Companies arrived to investigate. They didn’t have surveillance cameras back then, so he did it the old-fashioned way—by watching us. Specifically, he watched me. From the parking lot he saw me pretend to press the cash register keys while my buddies walked out with bags of filet mignon and caviar. He rushed in and grabbed my arm.

“Take off your apron and get the fuck out.”

I was fired, but so what. I had another scheme in mind. My next job was at Larkey’s, an expensive menswear shop in Paterson. Billy Stone and I worked as “pickup” guys—bagging the altered suits in the basement and running them up to the waiting customers on the main floor. It didn’t take too much of a pitch to enlist a handful of salesmen, black guys, to work with us. They had access to the merchandise on the main floor and in the stockroom. I instructed them to fill plastic garbage bags with Botany 500 suits and leave them by the dumpster for me to pick up later, promising them half the money we made selling the $500 suits for $200 to an outlet store.

This went on for six weeks, and in that time we stole forty-five to sixty suits, about sixty pairs of slacks, and shoes, making about $50,000. Until the general manager for all of Larkey’s, Guy Zoppi, hired a private investigator and planted him undercover on the sales floor—a move this chess master didn’t foresee. I recruited the spy, and a few weeks later a bunch of cops and detectives burst in and raided the place. The black kids got handcuffed, and I got sat down in a room alone for interrogation.

“You’re the kid who’s masterminding this whole thing,” one of the detectives said.

“We’re going to arrest you,” said a cop.

“I’m calling your parents,” said Mr. Zoppi.

This was not good. My father would take out his humiliation and anger on my mother. In that moment, I discovered a new talent to go along with my lying—crying on cue.

“You can’t do that,” I sobbed. “My mother’s sick. She’s going through ‘the change.’ If you tell her I’ve been fired or arrested, she’ll kill herself!”

My performance was worthy of an Academy Award for Best Melodramatic Bullshitter because it worked, and it earned me my high school nickname, “The Worm,” since I could slither out of any tight spot. The other guys were arrested, but they let me and Billy go without calling our parents.

Later that night, I drove to the phone booth in front of the North Haledon Fire Department and called Mr. Zoppi at home.

“What the fuck are you calling me for?” he asked.

“Please, Mr. Zoppi, I’m sorry!” I cried again. I was on a roll. “Those black guys at the store put pressure on me to steal. They scared me! I’m just a little guy. Um . . . can I have my job back?” I had balls the size of watermelons, but Mr. Zoppi busted them.

“Kid, you ain’t ever, ever, ever coming back.”

Click.

![]()

But again, I wasn’t without a scheme for long. Everywhere I looked I saw dollar signs and easy marks. My palms got itchy when I sensed a potential big score.

When the drama department at school put tickets on sale for the annual play, I bought one and a made hundreds of counterfeits at a print shop and double sold every seat. The night of the performance was pandemonium. I managed the school store for a few weeks until the inventory came up $12,000 short the first month. The worm wiggled out of that one, too, and I talked my way out of being expelled.

Stealing car parts was another mastermind of mine. We’d hit three outdoor car lots in three different suburbs and take the radios and tires off the Super Beetle Volkswagen bugs and Triumph TR6s.

The car lots didn’t have any fences or security cameras back then—it was a different world when people just trusted strangers not to steal their stuff. We’d go to the lots after midnight and pop the side windows with a screwdriver, reach in and open the door (no car alarms back then, either), pop the latch for the trunk, and get the spare tire. To get the AM-FM radios, Eddy stuck his hand under the dashboard and unscrewed the bolts. We were fast, at a speed of one minute per car, and we’d hit twenty cars per night. At $50 per car, we’d make $1,000 in a few hours. When the lots installed security cameras three months later, we adapted and got ski masks. I was unstoppable.

We started selling drugs to other students. I bought them in Newark from a guy from the Dominican Republic who sat around playing cards in front of a coffee shop. We made the exchange in the bathroom, then transported the drugs behind the emblem on my steering wheel. We could fit about $1,000 worth of drugs in that little pocket—pot, LSD, and orange sunshine—before taking them to my basement, where we sorted them out into little plastic bags.

Soon, I expanded our business distribution network and started selling to the guys who owned the “roach coach” lunch trucks parked outside the manufacturing plants in the area. “You wanna provolone sandwich?” they would ask their customers. “You want any pot with that?” Those blue-collar guys needed a little escape from their shitty, humdrum lives.

As treasurer, I kept the money we made in a metal cash box on the floor of my bedroom closet. We were more than a fraternity; we were a mini-mob. And I was its High School Capo.

With drugs came rock ’n’ roll, and the world was changing. Apollo landed on the moon in the summer of 1969 and Woodstock happened.

I drove up with Danny and another friend, Stan Parrot, on the Saturday night of Woodstock weekend, but a few miles from the stage, traffic came to a standstill. We pulled over and started walking in the rain and through the mud with thousands of others kids, getting high along the way. A mile from the concert, we could see the lights bouncing off the stage and hear the Who singing, Sometimes I wonder what I’m gonna do . . . ain’t no cure . . . summertime blues . . .

After Jefferson Airplane finished the night with “White Rabbit,” we slept in the car, soaking and stinking, and left in the morning inspired.

In junior year, Danny and I started our own band, the Sound Effect. Out of the petty cash in the metal cash box, I bought myself a Farfisa electronic organ and a Leslie 147RV speaker and got Danny a rhythm guitar. We practiced Hendrix, Cream, Vanilla Fudge, and the Who in Danny’s muddy backyard barn and performed at high schools and birthday parties. The kids came to hear music and to get stoned or fucked up, and we provided all three—a diversified portfolio, remember?

But with drugs come drug wars. And with drug wars comes violence. I wasn’t worried. I was building more than a crew; I was building a fucking militia.