We called it “legal corruption” and everybody got a piece of the pie.

Rotting garbage, burning flesh, and a steaming pile of shit—that’s what it smelled like.

The New Jersey Meadowlands dump on Route 20 in East Rutherford burned day and night, seven days a week. If you lived or worked nearby, you got that stink in your clothes, in your hair, and shoved up your nose so deep you never got rid of it.

When I was a kid, people used to say the Mafia dumped dead bodies there after a late-night hit. By morning, whatever happened in the night was shrouded in the thick, early fog.

My first legit job out of high school in the summer of 1971 was at Maislin Transport, a trucking company with an office fifty yards from the dump. The Maislin brothers owned thousands of acres in the area, including the dump site, on which a new, clean, shiny Giants Stadium would be built five years later.

Maislin was the largest trucking company in the country at a time when trucking routes could be worth millions, before Ronald Reagan deregulated the industry in 1980. Back then a company like Maislin had the power to “run lanes”—they were awarded exclusive contracts by the government to haul specific merchandise. The international runs were the most coveted routes, and booze was the most valuable, desired merchandise to transport. The drink of choice at that time was Seagram’s Seven Crown and Canadian Club whisky. This cargo arrived in New York and New Jersey from Montreal by one carrier only—Maislin Transport.

Ever since the Maislin brothers began their business in 1945, they continued the time-honored tradition of Al Capone in the twenties—the prosperous partnership of booze, cops, transport, and organized crime. You had to pay the government and the Mafia to get the liquor contract, then pay again to keep it.

In 1971, Maislin had ties with New York’s Genovese crime family and the most corrupt labor union of all time, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters—specifically, Teamsters Local 560 out of Union City, New Jersey.

My uncle Anthony was a proud member of Local 560, and it was his idea to get me a job at Maislin after I (barely) graduated from high school. He knew an important guy who knew an even bigger guy. His idea was for me to start at entry level and work my way up to truck driver and Teamster, like him. My father was livid—he wanted me to go to college and be an accountant, like him. Plus, he knew the trucking industry was mobbed up the ass.

“Don’t get involved with these people!” my father yelled at both of us. “These are bad people!”

“Mind your fucking business,” my uncle shot back. No one else talked to my father like that and got away with it. At 6′2″, Uncle Anthony towered over my father. He had a red mole over his eyebrow and a broad, ruddy face like a real old-time ginzo, an old Sicilian.

“Tommy can’t go to college,” my uncle said. “He’s a dummy. Well, actually, he’s really smart, but he won’t do good full-time at school; he can go at night. Right now, he needs to grow up and get a job.”

The following week Uncle Anthony took me to the Tick Tock Diner in Clifton to get approved by Maislin “friend” Anthony Provenzano—aka “Tony Pro.” Tony was VP of Local 560 and, I didn’t know it at the time, a caporegime in the Genovese crime family. He’d just gotten out of jail after doing time for embezzlement and extortion. Tony Pro was powerful because of his strong ties with Teamsters Union leader and Mafia associate Jimmy Hoffa.

Both names meant nothing to me; I was clueless about organized crime except for the kind I organized myself. What I was also clueless about then, and found out later, was that my own family was “connected.”

My father’s mother, Josephine Laplaca, was related to Pete Laplaca—the capo of the Gatto crew in the Genovese crime family. Which further explained why my father flew into a rage at the thought of me getting involved with these “bad people”: they were his own flesh and blood; they were his people. Which meant they were mine, too. My family pedigree, along with Tony Pro’s vouching, is what got me the job at Maislin. I was one of their own; I could be trusted.

Before I started the job, my uncle pulled me aside to warn me.

“These are mob guys, Tommy. Be polite. You gotta be careful. Keep your mouth shut. Be respectful. Don’t give them none of your attitude. And one more thing,” he added, “whatever you’re doing in the basement stops right now, you hear me?”

I nodded. With high school over, I was losing a lot of my drug customers anyway, so I put that on hold. It was kid stuff compared to the dangerous world I was entering.

The trucking industry in New Jersey was the most mobbed-up business in the country, followed by garbage. And my new boss, Alex Maislin, a Canadian Jew from Montreal, had his hands in both. Short, bald, and chubby, Alex was a conceited, flamboyant, powerhouse of a character who wore Yves St. Laurent suits and swaggered around the office with a pearl-handled, .45-caliber chrome gun in his belt, resting against his big belly. At lunch he got bombed on vodka, then spent the afternoon chasing the secretaries in miniskirts around his desk. When he talked to you, whether you were a cop, a mobster, a union boss, an employee, or some nice-looking tomato—he talked rough, with balls as big as the one that dropped in Times Square. Alex Maislin would be my first role model for the guy I later became.

“You’re gonna be my gopher,” Mr. Maislin told me at our first meeting in his office. “And you’re gonna go for this and go for that. And I’m gonna to start you off at $145 per week.”

That was double the usual salary for a job like that. I looked over at his gigantic bodyguard, Rocco, hovering in the corner, his thick arms crossed. Antonino “Argentina” Rocca was a former Hall of Fame wrestler who sang opera around the office, but never talked. He was like a mountain—big and immovable; he was Alex Maislin’s version of Corky Quant.

“All right, Mr. Maislin,” I said, in my polite voice. I could do polite.

“No, no, noooo. Tommy. Call me Mr. Alex.”

For the job I wore a tie and stuffed my shoulder-length hair under a Yankees cap. In my light-blue Super Beetle Volkswagen (I traded in my Chevy), I picked up lunches for the staff and dropped off Mr. Alex’s dry cleaning and picked up sports tickets; whatever Mr. Alex asked me to do, I did. I picked up groceries to stock his fridge in his mansion in Fort Lee, and drove his wife to the beauty parlor. When she interrogated me about Mr. Alex’s nineteen-year-old girlfriend at the office, I lied for him.

“He don’t have no girlfriend, Mrs. Maislin,” I’d say. “He’s a good man.”

I was already learning omertà—the Mafia’s code of silence. Uncle Anthony said to keep my mouth shut, so I did—especially about what I saw down at the loading docks late at night. Sometimes when I was walking through the terminal, I’d see a black Cadillac speeding past the security post and drive to the back. Two guys would drag a screaming guy out from the trunk and beat the shit out of him. In the middle of the Meadowlands, surrounded by acres of eight-foot wetland cattails, you could scream your lungs out and no one’d hear you. Just like the torturing of the frat dogs in the woods. It was the perfect place to whack someone. And, conveniently, the dump was right there to get rid of a body.

Mr. Alex loved me for my discretion and because I was fast, smart, immaculate, and never late. He told me to come in at 8 AM so I was there before 7 AM—setting up the ledgers, organizing his office, and laying out his booze. Every other day I took his 1972 Fleetwood Brougham black-on-black Cadillac with XXX license plates to the car wash and did the detailing myself—wiping the mats and the inside of the windows. Mr. Alex hugged me and kissed my cheek hello every morning and goodbye every night.

“You’re doin’ good, kid,” he’d say, slipping me a fifty-dollar tip. He kept three-inch-thick wads of C-notes and fifties in his pockets, held together with rubber bands.

My favorite task was to drive Mr. Alex and Rocco to Frankie & Johnnie’s Steakhouse in Manhattan, where they’d meet Frank Sinatra for dinner. I’d wait in the car playing “Nice ’N’ Easy,” with a smile, knowing Sinatra was just inside with my boss.

Sitting out there one night, I decided that I wasn’t gonna steal from Mr. Alex. I could have easily pinched the joint good; I had the keys to everything—the offices, the warehouses. I could have called up my old crew to bring their vans to the loading docks and fill them up—TVs, stereos, washing machines, musical equipment, lawn mowers, and furniture. My hands got itchy just thinking about it.

But the money Mr. Alex gave me got so good so fast, I didn’t need to. There was big money to be made at Maislin if I played my cards right. And Mr. Alex would shoot me with his .45 if I ever stole from him.

One afternoon in a drunken rage, he went after one of the dockworkers when he thought the guy had ogled Mr. Alex’s teenaged goomah.

“I’m gonna kill that sonofabitch!” he said, storming through the terminal with his gun to find the guy.

“Mr. Alex!” I ran after him with Rocco. “Calm down! You don’t need to shoot this guy. Fugghetaboutit.”

It was a phrase I first heard at Maislin, which was immortalized in the movie Donnie Brasco twenty-five years later. All the Maislin guys were saying it, and I was learning to speak their language. Hey, youse guys got da ting wit da ting wit da ting?

I even started getting my hair cut by the barber to the mob, Marty, who had a shop in Paterson. They all loved him because he was quiet and they’d sit in his chair and spill their guts and he never ratted. Every two weeks I was Marty’s first appointment of the day at 6:30 AM for a trim. No more hippie hair for me; he slicked it back like a real mob guy.

Mr. Alex calmed down about the dockworker and didn’t remember a thing the next day. The guy lived. Mr. Alex was so impressed with how I handled him that he offered to pay my tuition for night classes at Bergen Community College and William Paterson University, where I had just signed up to study business administration. He had big plans for me, he said.

Four weeks into the job on a hot and sticky August afternoon, I was summoned to his office. He was in his usual vodka-induced stupor with his loaded .45 dangling over his belt.

“Tommy, we got ten loads of Canadian Club coming in tonight from Montreal and the security guard called in sick. You’re gonna do security tonight.”

“What do you mean,” I asked. “All night?”

I’d overheard the dockworkers talking about overnight guards in the transport business calling in sick when they thought there’d be a hijacking. Liquor was a big target because, unlike TVs and stereos, the bottles didn’t have serial numbers.

This is how a hijacking went down: A car pulls up to the security post around 3 AM, at the same time the trucks carrying the booze arrive. The hijackers jump out with guns, order the driver out, take IDs from the driver and security guard, and say, “If you say anything, we know where you live.” Sometimes, they shoot the truck driver and the security guard. Sometimes, they died. The empty trailers were found a few days later, abandoned somewhere.

“Sit in the guard shack,” Mr. Alex continued, pouring a new drink, “and when the trucks come in, write down the trailer numbers and the times. It’s easy! I’ll pay you time and a half, and here’s an extra $100 bonus.”

I felt myself go pale. I looked over at Rocco—arms crossed and stone-faced.

“Hey, Mr. Rocco,” I whispered, “don’t you never talk?”

“What’s that, Tommy?” Mr. Alex asked.

“Oh, nothing, nothing.” Motherfucking guardhouse duty. I don’t need this shit.

“Tommy, you look a little nervous,” Mr. Alex slurred. “If you run into any trouble there’s a phone in there, call the cops,” he said. “Or . . .”

He took out his .45 and handed it to me. “Take my gun. Just start shooting.”

It was so heavy I fumbled and nearly dropped it.

I looked over at Rocco again. Now the wrestler in the corner looked nervous, too.

![]()

The guardhouse was a tiny shack fifty feet from the highway. It had a rotary phone on the wall and an air conditioner in the window, which I didn’t turn on. I wanted to make sure I’d hear the hijackers barreling down Route 20 when they arrived. I carefully placed the gun on the counter and opened the windows. Flies from the rotting-garbage-burning-flesh-steaming-shit dump rushed in. Motherfucker!

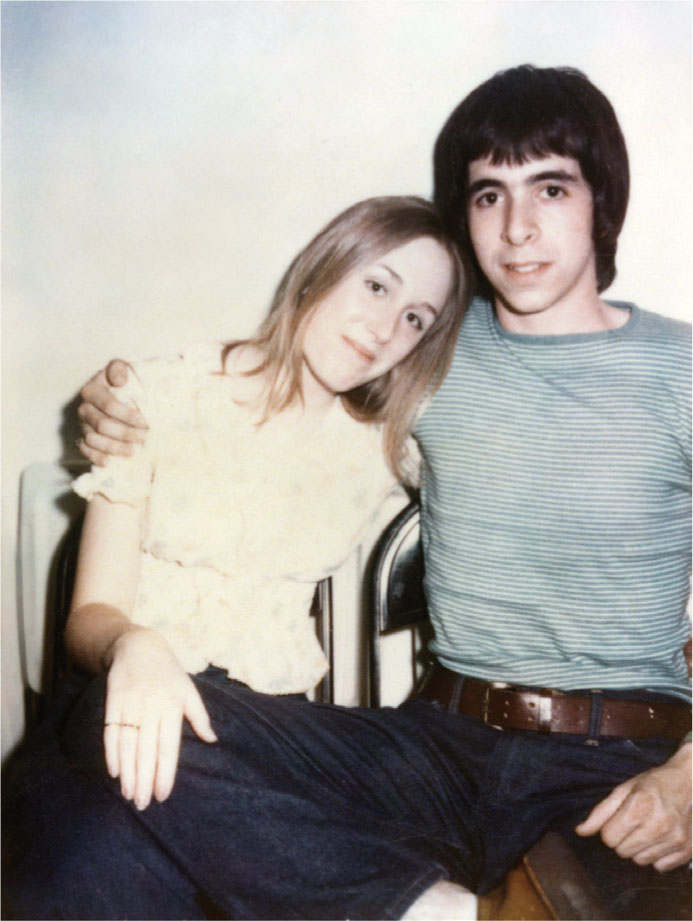

By midnight the fog began to roll in. I grabbed the phone and called my new girlfriend, Debbie Carini, a pretty blonde I’d met at the Jersey Shore on Memorial Day weekend. She walked past me in a blue string bikini and I reached out, grabbed a string, and pulled her toward me. Yeah, I was smooth with the broads all right.

“Hey, baby,” I said on the phone. “I’m scared out of my fucking mind over here.”

Deb and me, high school sweethearts

I called her every thirty minutes as the flies buzzed around me like vultures circling a soon-to-be-dead body. By 3 AM, the fog was so thick, coming in through the window, I could barely see the phone or the gun in front of me. But I could see a pair of headlights heading my way and it wasn’t a delivery truck.

Screw this! I thought. I grabbed the gun and ran blindly out of the shack to the truck terminal and crawled under a trailer. The fearless capo of Manchester High who vanquished his enemies months earlier with chains and firebombs was hiding like a sissy. Not my finest moment. But this wasn’t high school anymore; these guys were the real thing.

From the ground, I saw the wheels of a car idle in front of the guard shack, then I heard a boom-boom-boom. A few minutes later, the car was gone. I ran back to the guardhouse and called the police. When the cops showed up, I explained about the place being hijacked.

“Yeah, right kid,” they said, chuckling and getting back into their squad car, “not this place.”

The booze trucks arrived after that and everything was fine. And as the sun came up it finally dawned on me: other trucking companies got hijacked, but not Maislin—and for good reason.

The next day, I told Mr. Alex everything.

“Mr. Alex, please don’t make me do that fucking job no more. I almost had a nervous breakdown.”

“Jesus Christ, Tommy, take it easy,” he said, reaching into his pockets. “Here, take more money. You’ll feel better.”

He handed me two hundred-dollar bills. I smiled and looked over at Rocco, who grimaced in the corner. I just invented yet another way to get money—whining. Mr. Alex told me I’d passed an important test doing guard duty, proving my loyalty to him.

“I need loyalty, Tommy. I demand it,” he said, announcing I would now be promoted from gopher to runner. My new duties beginning the next day were to deliver briefcases “to certain very important people,” he explained.

One of my first regular runs was to the offices of the New Jersey Sports Authority at the new World Trade Center. In the fall of 1971 the iconic center was still under construction, but the lower half of one building was in use and already busy. The first time I stood in front of it on the street, I looked up in awe. The roof disappeared into the clouds.

Once a week I was sent to meet a man from the Sports Authority in the lobby and hand him a briefcase. I wasn’t told what was inside, but I knew damn well it wasn’t briefs. Bribe money? Several months later I went to that same lobby to fetch a big fat check from that same guy. Maislin had hit the jackpot and sold their East Rutherford property, including that stinking dump, to the Sports Authority as the site for the new Giants Stadium. The deal would make all seven of the already-wealthy Maislin brothers even more stinking rich.

Soon, another World Trade Center stop was added to my routine—the US Customs office. They were in charge of clearing the shipments that came in from Canada so, of course, the kindly customs agents received a weekly briefcase for their hard work and loyalty from their friends at Maislin Transport.

I drove my trusted Beetle to deliver money

By October, I was making out-of-town deliveries. I’d roll down the windows and play cassettes of Sinatra singing “Summer Wind” full blast in my Bug as I drove to Albany, Philly, Baltimore, and Cherry Hill to take top-secret briefcases to different Teamsters Union presidents. I was like Henry Hill in Goodfellas when he was a runner for the bosses.

Each time I left the office, Mr. Alex handed me a fifty- or one-hundred-dollar tip. Or he’d say, “Go put some gas in the car, Tommy, and keep the change.”

Why were the union presidents getting paid? Because it was their guys who drove the Maislin trucks and if they were ever to strike, your trucks stopped moving and your business was dead. An interruption in service could kill your business, so we had to keep the union bosses happy.

The only day I didn’t do deliveries was on Friday—that was State Police Day at Maislin. That’s when more than a dozen New York and New Jersey police captains, sergeants, and lieutenants came to have lunch with Mr. Alex. They had to be kept happy, too. On Friday mornings I’d go to the docks with a dolly and bring back cases of Seagram’s and Canadian Club to have ready in the office. After lunch, as they were leaving, Mr. Alex handed each one a few bottles and a briefcase.

“A little gift,” Mr. Alex would say.

It’s what kept our trucks from being pulled over by cops or hijackers, I finally understood. No one was gonna stop a Maislin truck if so many powerful people were making money off us.

I was learning the importance of bribe money, but we didn’t call it that. We called it “legal corruption” and everybody got a piece of the pie—including me.

I was making more money than I ever imagined, about $4,000 a month. For an eighteen-year-old kid, that was fucking ridiculous. Every other night I took Debbie to the Steak and Brew on 43rd Street in Manhattan, and we’d order the most expensive steaks on the menu and Blue Nun wine; we were some hotshots. After dessert, in the parking lot, we smoked the best pot that money could buy.

My father was going mental watching all this unfold.

“Where are you getting all this money?” he demanded. “What are you doing for it?”

He thought I was doing something illegal with the “bad people.”

The irony, if he only knew, was that it was the first time in my life since I was seven years old that I wasn’t stealing from someone, including him.

I was simply benefitting from other people’s corruption.