I was on fire. I blared my favorite disco tune, “Crank It Up,” on the radio as I drove around with my police shield. My heart was pounding-pounding-pounding.

I wore three pairs of white Jockey underwear on top of each other—we used to call them “Superman” underwear—under my pinstriped Pierre Cardin suit. They smoothed the bunched-up Ziploc sandwich bags I had stuck against my sweaty cogliones, my balls.

I had big balls, all right—stone fucking balls.

It was my first time smuggling cocaine and I wasn’t nervous. I shaved the tops of my thighs so that I could duct-tape the bottom of my underwear to my legs to keep the coke from sliding down as I walked and boarded the flight at Newark.

It was 1979 and they didn’t stick you in body X-ray machines or sic drug-sniffing dogs on you then. Those were the good old days. I was a top executive at Deliverance, with their official logo on my Hartmann briefcase, on my way to a meeting at our Indianapolis headquarters. Who’s gonna suspect I got drugs in my crotch?

After landing I met my new coke buddy at his apartment.

“Get this fucking shit offa me!” I said, dropping my pants to my knees in his kitchen and pulling at the duct tape. We ripped off my skin and I got the glue off using paper towels soaked in liquid Carbona. For a day, my balls would stink like gasoline mixed with turpentine. As soon as my balls were covered again, he handed me a manila envelope with $18,000 in cash. Easy money, my favorite kind.

When he gave me my first hit of coke that night in Grand Rapids a few months earlier, it was the beginning of the unraveling of the new-and-improved Tom Giacomaro—the one who shot to success in the trucking world using wit, charm, smarts and finally made his mother proud. The unraveling had begun, and in the end it would reveal the Tom my father always knew I was: the fuckup. The nothing.

I woke up the next morning after that first coke hit, called in sick at Allied, and spent the next three days getting fucked and fucked up with the strippers. My next few months in Michigan were more of the same. Coke, I discovered, wasn’t like my previous shitty Orange Sunshine trip. It was fantastic—it made me into Super Tom with a perpetual hard-on in my Superman underwear. And it made the girls wanna fuck all night.

Grand Rapids was the asshole of the world, but the strip clubs were filled with rosy-cheeked college girls rebelling against their Republican, Amway-cult families. They weren’t whores, exactly. I took them out to dinner and gave them drugs, but I didn’t pay for the sex—not with money, anyway. They loved the coke as much as I did.

When I finally returned to Jersey in 1979 to join Debbie and Lauren, I arrived an official cokehead.

The first two things I did was buy my first Rolex—an eighteen-carat-gold one with a diamond-studded face, paying $12,000 cash for it. Then I went to get my new Cadillac—a black, 1979, two-door Coupe de Ville with a burgundy interior, white-and-gold gangster Vogue tires, and chrome wheels—a real guinea car—over at Brogan Cadillac. Hard to believe that eight years earlier I was stealing car radios and tires. Before I left the dealership that day, I treated myself to a second car—a black Sedan de Ville with a red interior. The salesman, Freddy Minatola, said I was his new favorite customer. Little did we know he would soon be one of mine.

Debbie, Lauren, and I settled down in a Cape Cod house in Hawthorne that I bought for $87,500, then spent $100,000 to renovate. I sent Debbie, with Lauren, to her mother’s for two months while I slept in a cot in the living room to “oversee” the renovations. In other words, I took broads there and partied all night. The coke, the coke . . . how can I explain what the coke did to me and my life?

Before I left Michigan, I was made VP and became my coke buddy’s new East Coast connection.

“You need to find someone with access to large quantities of coke,” he said, excited. “You have no idea how much money we could make with this stuff!”

I had some idea, since I saw firsthand how easy it was to get hooked on it. But I hadn’t sold drugs since my pot-dealing days in high school, and my connections were rusty. There was only one person I could think of to call—my old KGL brother Stevie Moretti.

After I defected to Maislin, Stevie continued selling pot to my connections for a while and was now studying at some hoity-toity school in upstate New York. He’d gone straight, like me—until I called. (“Just when I thought I was out,” Michael Corleone says, “they pull me back in.”)

Sure enough, Stevie knew a guy who knew a guy. Within a few days, we were back in the drug-dealing business together in my mother’s basement.

I started off buying six ounces, once a week. I was our main buyer and Stevie bought his stash from me at a discount. Within a few weeks I upped the amount to eight ounces, then ten. Two months into it, I was buying and selling kilos. That’s when I bought my second Cadillac from Freddy—an Eldorado Biarritz with a beige interior.

Our drug dealer brought the coke to my office on Route 46 in Clifton—a mile from my old office at North American Van Lines—in a plain brown paper bag. He was a degenerate kinda drug dealer, nothing fancy. But his Peruvian coke was pure and gorgeous. So good, that by month four I was buying seven kilos at a time. That’s when I went to see Freddy again for my third Cadillac, a black Seville with a beige interior.

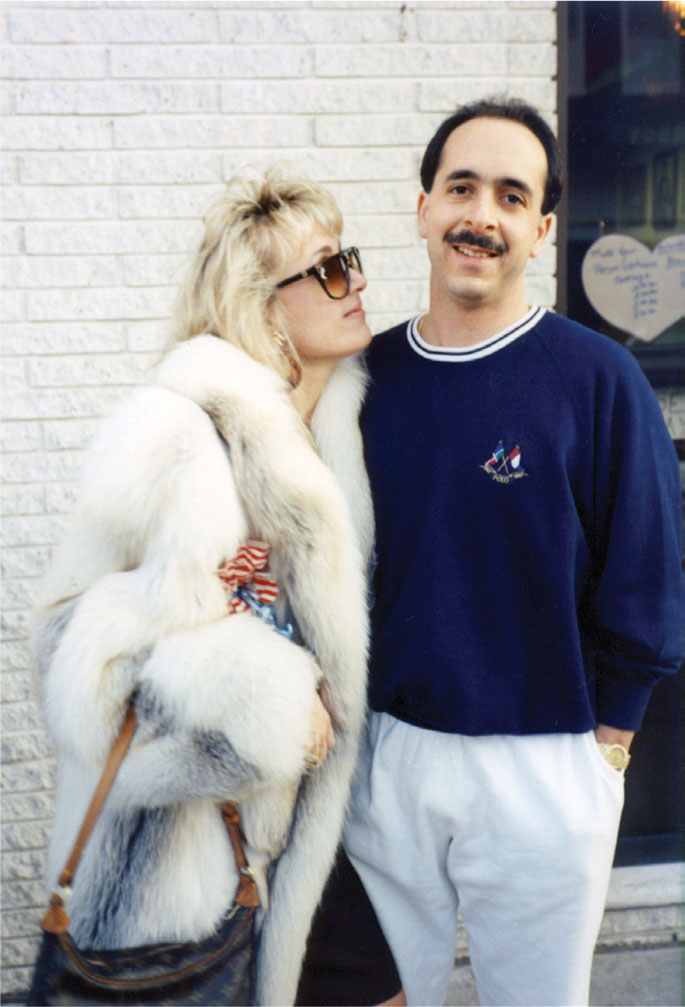

The coke dealer’s wife always gets a fur coat—with Debbie

Stevie stored the drugs for us in a rented safe house in West Paterson, but my mother’s basement is where we performed the smashing, cutting, weighing, and packaging ritual.

While my father was at work, we cleared the papers off his table where he did his accounting and tax work and lay down a cheap, plastic tablecloth—the kind old-fashioned Italians used on Thanksgiving and Christmas to protect the nice one underneath. Then we placed the coke in the middle of the table and covered it with a towel, so it wouldn’t fly all over the place when we smashed it. It looked like a big brick of hard cheese. Using an eighteen-inch-long machete I’d smash it until it crumbled, then pour it into a spaghetti strainer and grind it against the wire mesh with my fingers until it was the consistency of baby powder.

In a ceramic bowl, we cut it fifty-fifty with a powdered vitamin we got at the health food store—inositol hexanicotinate (IHN), a form of niacin. It looked like coke and was tasteless. When we were done, it was a big sand dune of white dust.

I poured it on a triple-beam scale using flour scoopers for weighing, then divvied it into separate Ziploc baggies, one ounce per bag. We rolled up and burped each baggie to get the air out, then double-bagged them.

The entire production took four hours, and by the end, we were high as kites. In prison more than two decades later, I found out why. As we handled the coke with our bare fingers, we absorbed it into our bloodstream through our pores. Who knew?

The final task after we removed our equipment was to scrub my father’s desk clean. The son of a bitch would have noticed one speck.

![]()

As we got our drug cartel off the ground, Stevie and I started another side business, buying a dumpy little travel agency in Paterson. The owner, Joan Reiser, was married to the chief of detectives for Passaic County, Oatsie Reiser. It was a connection we knew would come in handy in our new line of work. Oatsie was good friends with all the New Jersey politicians and cops, and if there was one thing I learned from Mr. Alex, it was to be nice to cops—really nice. Oh, yeah.

We kept Joan on as manager and kept the name, Reiser Travel Agency, so that everyone could see we had the law on our side. We used the front part of the office for the travel agency and hired pretty girls in tube tops and jumpsuits to answer the phones. The back part we used for Deliverance and our drug business.

Buying the travel agency was just a way to get closer to the cops and buy them. I’d seen Mr. Alex do it with his briefcases full of cash and “gifts” of booze, and now it was my turn. I wanted one of those gold-and-blue police shields to put by my car’s back windshield so cops wouldn’t pull me over and so I could park wherever I wanted.

“Ya gotta make a ‘donation’ to the Jersey State PBA—the Policemen’s Benevolent Association,” Stevie said.

The next time I saw Oatsie at his club, I did. The Reiser Social Club was kind of like John Gotti’s Ravenite Social Club in Little Italy, but a guy cave for the noteworthy Democrats in the area—firemen, detectives, state police, senators, and congressmen. Stevie and I went on Sunday mornings to get chummy with the cops and politicians so they’d keep their mouths shut about our cocaine business. We donated generously to the club, to their political election campaigns, and to the Benevolent Association. Sometimes, we donated directly to Oatsie, if you know what I mean.

“For the Benevolent Association,” I’d say, handing him an envelope with a $25,000 check.

I got my police shield immediately. As long as we “donated” on a regular basis, we never got into any trouble. And so, we expanded our business.

![]()

While my Indiana buddy sold coke to buyers there, Stevie and I developed our own client networks in Jersey. Stevie reconnected with our old “roach coach” vendors parked at the local factories, and I gathered a group of friends to sell to: Freddy Minatola, who sold me my Cadillacs, became a regular customer. So did a few of my childhood buddies. I also sold to the waiters and restaurant owners in North Jersey, who sold to their patrons. In the mid-to late seventies, cocaine was the big high and everybody wanted it, everybody was doing it. Walk into any bar or club and people were doing lines in the bathroom.

By month eight of our cocaine business, I was grossing $200,000 a week and I was on fire. I blared my favorite disco tune, “Crank It Up,” on the radio as I drove around with my police shield. My heart was pounding-pounding-pounding and my days ran at fast-forward speed.

We recruited a team of “runners”—friends, freight salesman from conventions, guys we partied with—who became our airport mules. We were transporting so much coke out of town that Stevie and I taped the pouches of drugs under their armpits as well as in their underwear. We sent our mules to Detroit, St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Des Moines. It was helpful to own a travel company so we could get airline tickets on the cheap.

By month ten, Stevie and I had a dozen safe houses all over North Jersey. We stored drugs in walls and ceilings of townhouses and in boxes of refrigerated iceberg lettuce in restaurants. Coke absorbs scents, so packing lettuce around it keeps it smelling clean.

The more coke we bought, the more coke I snorted, the more my pulse raced, and my life crumbled.

At first, I used it mainly as a party drug. It was the death rattle of disco and Stevie and I did lines and then went to Studio 54. I’d slip the doormen and bouncers hundred-dollar bills and we’d walk past the long lines waiting behind velvet ropes. I wore silk shirts unbuttoned to my navel, with my 18K gold chain and cross against my chest. And a Rolex, always a Rolex—by then I’d bought five more.

Within the year, by the end of 1980, I was carrying around a vial of powder in my pocket and dipping into it every hour with a little gold spoon I bought at a head shop. My respiratory and nervous system rode a continuous roller coaster—up and down, up and down, pounding-pounding-pounding—with one ride leading seamlessly into the next.

John Lennon died and I barely noticed. I was doing coke all morning, then started drinking at 3 PM to bring myself down enough to have business dinners with my Deliverance clients—vodka became my poison, just like Dad. I took clients to a hotel in West Orange where Connie Francis and Liza Minelli performed, and they came by our table to say hello. I wanted to tell Liza that The Wizard of Oz saved my sanity when I was a kid but I was too fucked up to say the words. I think I said something like: “Toto . . . home . . . man behind curtain . . .” and that was pretty much it.

At my Deliverance dinners I’d invite Ira from Toys “R” Us, Tom from Samsung, Joe from Emerson Quiet Cool, and their various wives, girlfriends, or mistresses. I’d call out to the waiter:

Bring us eight bottles of Château Lafite Rothschild!

And Dom Pérignon!

And Louis XIII cognac!

Money was no object on my limitless expense account, especially after I’d excused myself a few times to go to the bathroom and do more coke.

When my business dinners were over, Stevie and I did more coke before hitting the nightclubs and strip joints to pick up broads to bang. At 6 AM, as the sun rose, I’d finally get home. This went on almost every night.

After I made it up the circular stairway at home, I’d stop by Lauren’s bedroom door and peek in. Sometimes I went in and watched her sleep. She was there; she was safe. She was the only good, pure thing about me.

The only way I could get to sleep was with quaaludes. They made me crash for two days, and my Indianapolis buddy had to cover for me with the big bosses there. He didn’t care what shape I was in as long as I kept our top accounts going (I did) and kept the coke coming (I did).

He didn’t care, and Debbie didn’t realize how bad it was getting. But I did.

I was starting to get paranoid, thinking everyone was watching me or following me or looking at me funny. I was jittery; I couldn’t breathe. I could hear my heart pounding against my ribs the skinnier I got.

One afternoon I drove my Cadillac northward to Seven Lakes Drive in the Hudson Valley, winding up to Bear Mountain, where my father had taken me as a kid once and we’d had a good day. I’ll be able to breathe there, I thought. I drove up as high as the road would take me, parked, and sat on a rock overlooking the valley. The day before, Debbie had told me she was pregnant again.

“What am I doing to myself?” I asked out loud, to no one.

![]()

Tom Jr. was born in June 1981 and again, I was in the delivery room. When he came out, I held him in my arms and kissed his forehead, speechless once more. I knew I’d never be home for him either, but I wanted kids—lots of them. I wanted the big family I never had as a lonely, only child, and I wanted them to have each other. I felt protective over them and, yes, I did love them. I just had no idea how to love them or how to be a family man.

I knew how to make money. By the fall of 1982 I was raking in $300,000 a week in cocaine sales alone. My salary at Deliverance, now $150,000 a year—I got a raise after bringing in Zenith and RCA—was pocket change in comparison. Debbie and I moved to a big house in Wyckoff—I paid cash. She bought furs and wore Jackie O sunglasses.

I had so much cash I didn’t know what to do with it. I started storing it in shoeboxes in the basement. I’d put $10,000 in each box, duct-tape them shut, and stack them. At one point I had eighty boxes in the basement, that’s $800,000.

I wasn’t even thirty yet, but I was worth millions. And that made me the cockiest, most arrogant fuck you’d ever meet. Which is how I walked into Gaspar’s Nightclub one night with Stevie, tossing hundred-dollar bills at the staff. Gaspar’s was the hottest place in Jersey and I knew the owners well. It was hopping with broads and a haven for selling drugs. I had my own table and made drug deals downstairs in the basement.

That night, in the fall of 1982, I walked in with my cocky attitude and noticed a hot blonde and two mob guys at the table next to us drinking and doing coke on the sly using snuff bullets. I’d seen them around and they’d seen me.

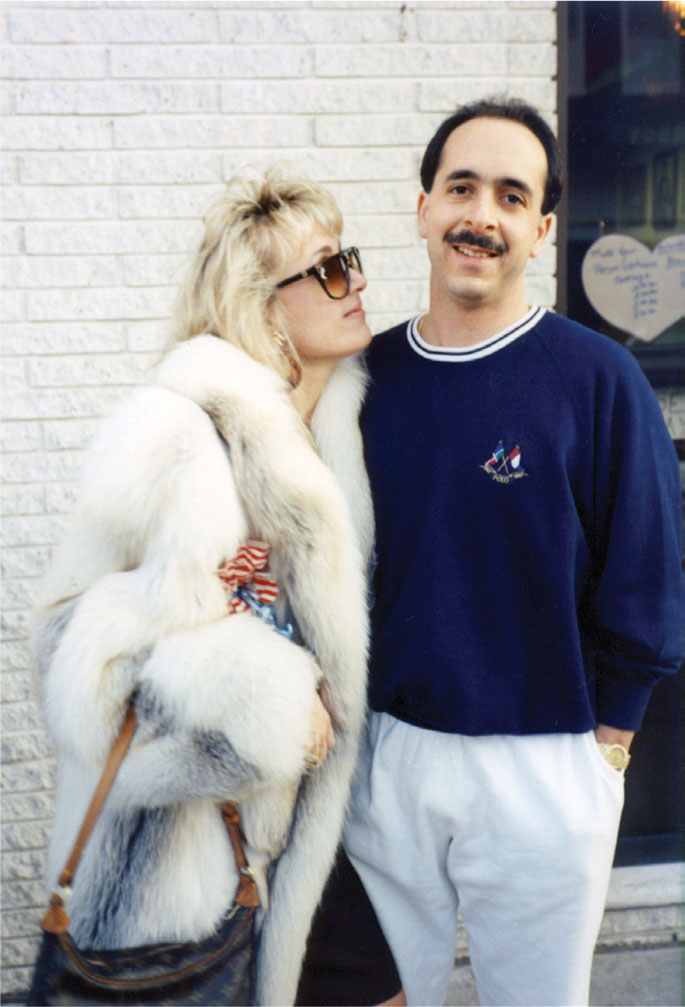

Frankie Camiscioli (“Frankie Cam”) and Joe Albino were two associates of the Genovese crime family who ran numbers and sports. Their boss was Genovese capo Lou “Streaky” Gatto, who’d taken over a few years earlier. The Gatto crew controlled illegal gambling, loan-sharking, and bookmaking rackets in the area and was known for their violent methods and shrewd business deals. The blonde was Kim DePaola, whose mother, Dotty, was married to the head of the Assassination Squad, “Murder Incorporated” for the Gambino crime family.

Frankie Cam

With one glance I could see that Frankie—loud and stocky like a pit bull—was The Muscle and Joe, a quieter, James Caan lookalike, was The Brains. Kim was The Broad. I introduced myself.

“We’re in the numbers and sports business,” Frankie said to me, over the synthesizer beat of Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love.”

“Yeah? Well I’m in the trucking business,” I said, eyeing Kim.

“Yeah? Well, it just so happens that we’d like to expand into the trucking business,” said Joe.

“Oh yeah? You got that kind of money to expand into trucking?”

“Oh, yeaaaah,” said Frankie. “We got tons of money.”

The next day I met them at Joe’s house in Clifton to talk business. I already had cops in my pocket, I was thinking. Add a few mob guys and I’d be protected across the board. Joe had put out a spread—cold cuts, rolls, this and that.

“We want to go fifty-fifty with you in a trucking company,” Joe began.

“Oh yeah? Well, I don’t see what you have to offer me,” I said. “I’m already the biggest and the best in trucking because I have all the important accounts. What do I need you for?”

“We’re organized crime,” Frankie said, proudly.

“That don’t impress me much,” I said. “No one’s more organized than me.”

“We got control over at the Teamsters; the union guys work for us.” Joe continued, “We’re with the Genovese crime family.”

“Oh, yeah?” I cut him off. “Well, I got my own Teamsters contacts. And I gotta be honest wit youse guys, I’m with the Giacomaro crime family.”

That shut them up for a minute. Frankie looked confused; Joe looked hesitant. And in that moment, I decided that these two dumb goons could be useful to me. They were mob, but they’d be easy to control. And starting up a new trucking company was a good idea. Deliverance couldn’t handle the amount of business I brought in; there was always a surplus and my contacts went elsewhere to pick up the slack.

“You guys know I move cocaine, right?”

“Yeah. You can’t tell anybody you do that,” Frankie said. “We’re not allowed to do coke; our boss won’t let us.”

“Fine.”

We stood up and shook hands.

“Next week, we’ll take you to meet our boss. You’re wit us now.”

Fuck. I didn’t want to meet Streaky. He’d wanna get his claws into me and my legit business and make me a “made man” and tell me what to do and fuck everything up. No way. I wanted their protection and connections, but I wanted to do things my way, as always.

“Lemme explain something to you so youse understand,” I said, still gripping Joe’s hand. “I ain’t wit you guys at all. You’re wit me.”

![]()

But there was no getting around it. The next week we set up our new corporation, Lone Star, and looked for warehouses. And I went for my first Mafia sit-down with Lou “Streaky” Gatto.

We met at Vesuvius in Newark. Streaky sat at the head of the table, flanked by his sons, Joseph and Lou Jr., and his son-in-law, Al “Little Al” Grecco. Streaky was a skinny little guy who barely spoke, but his ego was big enough to suffocate the entire restaurant. Little Al did all the talking and as he spoke, Streaky systematically placed hundred-dollar bills, one at a time, in between his knuckles, made a fist, and held each up in the air. One by one, waiters came up to him like moths to a flame, kissed his hand, and took a bill.

“Thank you, Don Luigi,” they said, worshipfully.

Fucking son of a bitch, what a freak show. Meanwhile, Frankie and Joe were sitting at either side of me shoving sausages, peppers, and pasta fagioli in my face. I had my usual coke-vodka-quaalude hangover so all I wanted to do was vomit.

“I don’t want to eat this fucking shit, Frankie,” I whispered. “I’m gonna throw the fuck up!”

“Just eat the fucking food,” Frankie whispered. “You’ll offend Mr. Gatto.”

While waiters kissed Streaky’s fist and I struggled to hold back my retching, Little Al began his pitch to me. As a salesman, I wanted to give him some advice: this was not the best time to suggest a merger. But I was too nauseous to even try.

“Tommy, we want you to consider being with us all the time,” he said.

“Explain to me what that means,” I asked.

Little Al raised his hands and made a gesture that looked like praying, then he pulled his hands apart.

“We wanna open up the books for youse,” he said.

Goddamn it. Can’t the guy be clear and just say it?

“You want me to become a made guy, is that what you’re saying?”

“Yeah,” said Little Al. “We got big plans for you.”

Their plans, I knew, included me giving them a percentage of my own money every week—which is what Joe and Frankie did—and them using Lone Star to launder money. It meant they’d own me.

I’d had enough and wanted to get out of there. I suddenly had less than zero patience for this. And dammit, I needed a hit.

“You must be kidding,” I said to Little Al. “What could you possibly offer me that I don’t already have?”

Frankie kicked me under the table. Streaky looked like he wanted to leap across the pasta fagioli and stab me in the eye with his fork. I didn’t care; this salesman wasn’t for sale. But I was still a salesman, so I repeated my question to Little Al, but nice.

“What I mean to say is I’ll consider what you said. Thank you very much for lunch and I’ll let you know. In the meantime, Mr. Gatto, we’re going to make you richer than you can imagine.”

His ears perked up at that. They had plans for me? Arrogant assholes. I had my own plans.

I planned to use the mob for everything they had, but never be one of them. I planned to infiltrate the world of organized crime all the way to the top, but never be made.

The only crime boss I planned to answer to was myself.