South Africa had no extradition laws or treaties with the US, so I could disappear there forever behind my walls of stone.

Outside the gates of my villa near Johannesburg, hundreds of homeless squatters slept in urine-soaked, rat-infested cardboard boxes. Behind the gates, I was living like an American king.

My seven-bedroom, palazzo-style home had a tennis court; a 50,000-gallon cascading waterfall swimming pool; two brand-new 750Li BMWs in the driveway; and a stone fortress surrounding it. At the snap of my fingers, maids dressed in pink, ruffled uniforms brought me vodkas by the pool.

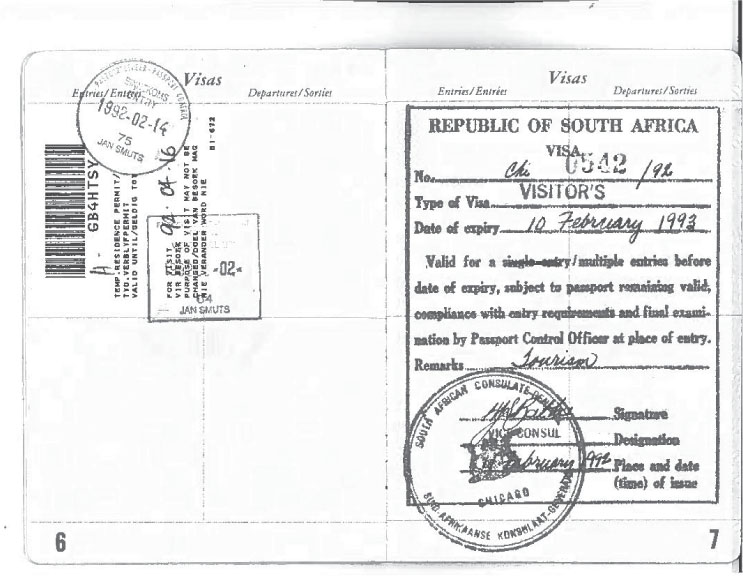

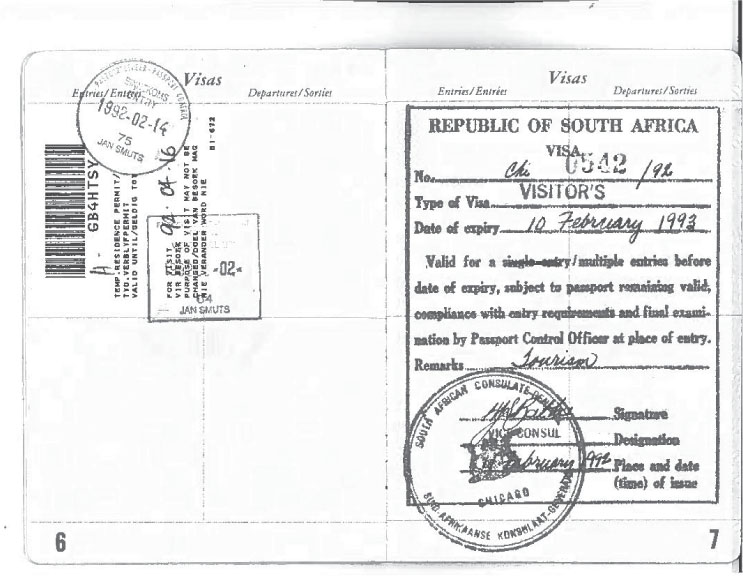

I arrived in South Africa on Valentine’s Day 1992, a wanted but filthy-rich man.

Half the twenty-one suitcases I packed were stuffed with hundred-dollar bills. And there were the millions I’d been secretly moving out of the country for years. I was The Worm, but I was also prepared just in case my ass was ever nailed to the wall. I had set up my exit strategy as soon as I started making shitloads of money selling coke, when I’d returned from Michigan a decade earlier.

Back then you could waltz into any top bank in Manhattan with your ID and without filling out reams of paperwork, open up numbered bank accounts in international branches in Sweden, England, Germany, Italy, France, and Switzerland. It was all so easy, so easy. In the years leading up to South Africa, I moved out $600–$800 million in total, the government wrote in their files later. Give or take ten million. Once I knew Kate had friends in South Africa and that’s where we were headed, I wired money there from my European banks. South Africa had no extradition laws or treaties with the United States, so I could disappear there forever behind my walls of stone.

Kate and I landed in Amsterdam from Detroit, then boarded a flight to Nairobi. When we arrived in Kenya we had to go through customs. The airport was swarming with security guards armed with machine guns, and there was the matter of my suitcases full of cash. I slid my Rolex from my wrist and dangled it in front of the security guy in charge. His eyes lit up.

“Come with me,” he motioned with his hand, quickly pocketing the watch. It don’t matter where you are in the world, the language of money is universal. In Swahili, he ordered several guards to transfer us with our luggage directly to the plane to Botswana, bypassing customs and security checks. From Botswana, we took a small plane to Johannesburg. Within a few days we were lounging by the cascading waterfall in the backyard of my new villa, downing Absolut on ice and sitting pretty under the hot sun.

My first few weeks there, I tried not to think about the giant fucking mess I’d left behind in Jersey. I distracted myself from the disaster I’d made of my life and everyone else’s by staying drunk and playing tennis with Kate’s friends, Mitch and Dina, a couple who owned the a chain of restaurants in South Africa.

Meanwhile, back home in the dead of winter, all hell was breaking loose.

I finally called my mother after two weeks to let her know I was alive, and she was relieved, but panicked.

Passport stamped at Jan Smuts International Airport in Johannesburg, February 1992

“Tommy, the FBI are all over the place turning everybody and everything upside down,” she whispered. “They’re investigating all of your friends. They’re watching me and your father.”

I wasn’t sure if she was whispering so my father wouldn’t hear, or because she thought the phone was tapped. I’m sure my father was beating the shit out of her more than usual because of the new, even bigger shame I’d brought on the family.

In the year leading up to my Valentine’s Day massacre, I’d left those 20,000 people out of work and billions of dollars missing from all over the place. Now, the FBI descended and grabbed anyone associated with me—asking questions and gathering testimonies. All my friends and colleagues were calling my mother, she whispered—Teddy Duanno, Patsy Giglio, Stevie Moretti, Tina, Miguel the driver, Maggie my bookkeeper . . . the list went on and on. I hadn’t told anyone I was leaving; I just vanished. After I left, any business I was still connected to collapsed.

Like Tina said once, it was like a napalm bomb had detonated.

Everyone was looking for me and screaming at each other: Is he dead? Where is he? What is going on?

But mostly, my former colleagues and the FBI wanted to know: Where the fuck was all that money?

“I don’t know!” my mother answered, over and over, to every question. “I don’t know, I don’t know!” And it’s true, she didn’t. Except for the suitcases of cash I’d hidden in the basement.

I sat back in my subtropical paradise eight thousand miles away, drunkenly looking at my waterfall, and for the first time in a long time I felt regret—mostly for myself. I’d been on top of the dog-shit pile with Zitani and I’d let it all collapse. Why?

Then I worried that everyone was gonna rat on me and fry me. I had set up Camino, Barnetas, and Kapralos to do the dirty work, and their names were on all the official paperwork. But by now, after a year of surveillance, the FBI would know I was, as always, the mastermind behind all the bullying, buying, looting, and busting. Enzo taught me, but I was a student who surpassed his master. I manipulated them all, and that’s what they’re all gonna fucking say when they rat.

Maggie was the only one who knew about my overseas accounts and where I kept the file with my meticulous, handwritten records. When the FBI brought her in and interrogated her, she wasted no time telling them where all the money was and, yes, she’d show them everything if it meant saving her own ass. But when she went to look for the file in the Clifton office, it wasn’t there—I’d cleaned everything out weeks before I left. Now Maggie looked the dummy and she made the FBI look like dummies, too. Humiliating the FBI was the worst thing you could do. They fried her for it.

By the time Maggie and the FBI saw that my files were missing, I was liquidating into diamonds all the money I’d wired and carried with me. In South Africa, they let you bring in millions of dollars—they encouraged it as an investment in their economy. When I wired my money, I got a 1:4 ratio conversion for every US dollar to the South African rand. Once the money was in the country, though, they didn’t want you to take it out. They had a $20,000 limit to how much money you could leave with.

But they didn’t mind if you bought a few of their homegrown trinkets to take away. South Africa was rife with underground and open-pit diamond mines and had been diamond crazy ever since the largest gem-quality diamond—over three thousand carats—was found in one of their mines in 1905. It just so happened that De Beers had its world headquarters in Johannesburg. And it furthermore just so happened that Kate’s buddy, Mitch, knew a VP there at De Beers who’d help me buy more diamonds than your average tourist.

I didn’t consider myself a tourist; I planned to stay in the country and make a fresh start. After a few weeks of drinking and tennis, my brain couldn’t stand being idle anymore and I was ready to get back to work plotting and scheming. I was going to take over the trucking business in South Africa, I’d decided.

I was delusional, of course. Thinking I could re-create my life with a new company, a new country, another big house, another beautiful girl, another expensive car—and not have to go back and answer for the mess I’d left behind. Extradition treaty or not, there was no way someone wasn’t gonna come after me sooner or later.

But for a while at least, I was able to convince myself I was safe behind my walled-in paradise.

![]()

The reality outside my mansion gates was a whole other chaos.

After twenty-seven years in prison, political revolutionary Nelson Mandela had been released, and two months before I arrived in Johannesburg, he’d given a speech at the Johannesburg World Trade Center in front of 228 delegates from nineteen different political parties to denounce current president de Klerk’s regime. South Africa was shifting from an apartheid government to a democratic one, and I saw the country transform before my eyes.

One afternoon I was doing some banking downtown and I left the building using the wrong door. I stepped into the street and into a crowd of thousands of South Africans marching. I was swept up, engulfed, and pulled forward with the throng and couldn’t get out. Military trucks were moving in, and men with swords and shields started hosing people with water to get them to disperse. It was a matter of minutes before the guns would come out and shooting would begin. I got soaked, but was able to slip into an alleyway and run.

Thinking as I do, I intended to use the political upheaval to my advantage and got to work wooing the people around Mandela. It didn’t take much to lure them. The black people in South Africa would finally be free to make money and attain positions, and they were about to take over the banks and the economy. I was a white businessman with millions of dollars to spend, ready to start up my company and pay them more money than they’d ever seen. What was not to like? Again, since this was before the internet, they couldn’t go online yet and find out about my past in America.

I zeroed in on the black guys prepping to be in Mandela’s administration and did my usual—took them to expensive dinners, got them drunk, partied with them, promised them big salaries and VP titles, and I slipped them cash. One of the guys, Magabi, later became a big official in South Africa. I could see his potential and made it a point to get especially friendly with him.

Every few weeks, I called home to Jersey to talk to my mother and Lauren and check in with my lawyer in DC. The calls were always the same: Lauren would cry and beg me to come home; my mother whispered about strange cars parked outside the house; and my lawyer warned me I was in big, big trouble. The FBI was issuing arrest warrants, he said, and he strongly suggested I come back and do damage control. Enzo Camino was all over the newspapers that month trying to get a new trial and get out of prison. There was a chance, my lawyer warned, that they’d find out where I was and come get me.

“It’s better if you go to them, Tom,” he advised. “You’ll be in a position of more power.”

I didn’t want to think about it.

Kate and I took off to Botswana for a few days with Mitch and Dina to have some fun. The capital city, Gaborone, was like Vegas. It had a long strip in the city’s center bustling with restaurants, casinos, and tourists. To get there, we drove along dirt roads through a maze of thatched grass huts, thorn trees, and donkeys roaming around the city’s outer edge—real backward, third-world stuff. As Mitch drove, I stared out the car window, and people stared back at me as we passed. Some had painted faces and wild eyes and they looked stoned out of their minds. I heard faint snippets of chanting coming from the huts.

We stayed at a casino-hotel owned by an American hotelier, and in the bar the next night over dinner I knocked back vodka after vodka, nervous about the FBI at home. I was also jittery because it had been three months since I’d snorted coke and I was jonesing for the devil’s drug. I didn’t take the chance of bringing any with me and hadn’t found a local drug contact yet. I thought about the wild-eyed, stoned-looking tribesmen we’d passed. From the casino window, you could see the tops of the thatched roofs.

“What the fuck is going on in those huts?” I asked our friends.

“That’s the Bakgatla tribe,” Mitch said. “They do ceremonies and rituals to get the evil spirits out of you.”

“Exorcisms?” Kate asked, interested. Tina and my mother weren’t the only ones who’d told me I was “possessed”—Kate had said it, too.

Mitch and Dina nodded. The exorcisms performed in the huts, they explained, were common practice in the country and part of the natives’ religion and culture. Everyone did it, tourists too. The belief was that everyone was possessed in some way or another and the only way to get unpossessed was through one of these exorcisms.

“There are evil spirits all around us,” Mitch said, ominously.

“You fucking believe in that shit?” I asked him, laughing, while downing another vodka. All three of them looked at me, dead serious.

“All right, let’s fucking go.” I stood up, unsteady. “I wanna do it.”

My whole life I’d been hearing there was something seriously wrong with me, from a lot of people. Maybe they were right; maybe I was possessed. Maybe a tribal ceremony on the other side of the world with people dancing around chanting mumbo jumbo would cure me of who I was. Or, maybe it was the six straight vodkas talking.

![]()

Mitch and Dina stayed behind, and Kate and I drove along the dirt roads until we reached a hut that seemed like the kind of place that gives a good exorcism. It looked creepy, silhouetted by the moon. I looked up. Great. A fucking full moon.

Kate waited outside and I paid a woman $500 before she led me inside.

The hut was decorated with candles and masks that sprouted grass and leaves— “They are gods,” said the woman, with a heavy accent. She pointed to a straw mat on the floor and told me to lie down. Another woman entered the room carrying something that was burning and stank to high heaven. At first I thought it was incense, until I felt that familiar high school feeling of being stoned. Ha! It had been so long! A few minutes on the ground and I was high as a kite.

The two women, black as night, were smoking something on their own as they painted me with a mixture of . . . did she say chicken’s blood? Oh, yeah. This oughta scare those evil spirits out of me. Jesus Christ. I let my mind drift as my two exorcists started dancing and chanting. I saw images all blurred together of Lauren crying and homeless people in cardboard boxes and piles of stolen money falling from the sky and my father’s demented face.

The image of his face made me vomit, literally. I puked into a bucket by the mat, and puked and puked so much, I thought I was gonna choke on the regurgitated vodka and steak coming out of me.

Then came the sweats and hallucinations, in which I thought I saw a black shadow leave my body, slide along the dirt floor, and slip under the wall of the hut to the outside where Kate was waiting for me, smoking a cigarette. I passed out.

When I woke up, I was out of the hut in the cool night with Kate. She was shaking me and trying to get me into the car.

“Bad Tom is all gone,” I slurred, as I lay down in the back seat and Kate drove us back to the house. “We’re safe now.”

![]()

But we weren’t.

A few days later at the start of the US Memorial Day weekend, I was sitting by the pool still recuperating from my exorcism when one of my three-hundred-pound maids in pink handed me the phone—it was my lawyer. The FBI put a trace on Debbie’s phone and knew where I was because of my calls to Lauren.

“Tom, you gotta get out of South Africa—fast. You’ve got to come back. They’re coming to get you with a burlap bag. Never mind extradition papers. They’ll kidnap you and smuggle you back to the United States. You’ve got about eight hours to get out of there; they’re on their way.”

I knew all about that burlap bag. They throw a potato sack over your head, handcuff you, and suddenly you’re in the cargo area of a US Air Force plane chained to the wall. It’s what they did to former Panama dictator and drug lord Manuel Noriega. These people don’t play around.

I had a plan, but I had to move fast and be efficient.

I ran upstairs into the bedroom with a needle and thread, a pair of white Ralph Lauren dress socks, and a small mountain of flawless, sparkling 2.5- and 5.5-carat diamonds—worth $10,00 to $100,000 each—on the bed. Kate was running around emptying drawers into suitcases. She was a pampered princess; she wouldn’t know how to use a needle and thread to save her life. But I did, thanks to my mother. “You never know when it’s going to come in handy,” she used to say, when she taught me how to baste and cross-stitch when I was a kid.

I chopped off the elastic tops from three socks and carefully poured in my diamonds, evenly distributing them among the socks. Then I expertly sewed the tops of the socks back together until I had three, perfect, two-inch-wide balls lined up on the bed. They looked just like a plate of fresh mozzarella. In the bathroom, I shaved my thighs, then slid on two pairs of briefs and ever so carefully placed the three diamond balls into my briefs, under my privates. That made five balls, I noted—I was a numbers guy, after all.

Over that, I slipped on a third pair of underwear and, using surgical adhesive, taped down the bottom edges of my briefs onto my hairfree thighs. Unless someone slipped their hand under the waistband to spontaneously gave me a hand job, those diamonds weren’t going fucking nowhere. I practiced walking back and forth in the room, trying to look like I didn’t have millions of dollars in my crotch. I was known for having big balls, but this gave a whole new meaning to the phrase “family jewels.”

Within hours of my lawyer’s call, Kate and I pulled up to Johannesburg’s Jan Smuts Airport (as it was called at the time) where I parked my BMW and tossed the keys into the trash.

I left everything—the house, the cars, the new company I was building, and at least $7 million in the bank I didn’t have time to clean out. My government friend, Magabi, called in a favor at the airport and arranged for our luggage to be checked in ahead of us so we wouldn’t cause suspicion, and booked us on a 2 AM flight to Nice, France. Our next hideout destination: Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, where Kate had a “very rich and very crazy” friend.

“The FBI could land on the tarmac and pull you off,” Magabi warned. “There might even be a passport hold on you. We won’t know until you get to the airport and try.”

I got through security and onto the plane, but until it took off, I was as nervous as a whore in church. During the ten-hour flight I barely moved. All I could think was: You can cut glass with diamonds and I’m sitting on a small mountain of them under my balls.

I didn’t breathe until we landed in Nice.

Not only had we eluded the FBI, but I found out soon after landing that we narrowly missed one of South Africa’s most brutal, bloodiest outbreaks of violence during the revolution—the Boipatong massacre, in which forty-five people were murdered in a township twenty-five minutes from my house.

In Nice we crashed with Kate’s hottie heiress friend, Karen, in her villa overlooking the Mediterranean. She came from a billionaire family that made money in newspapers and copper mining and gave her a $40,000-a-month allowance. She was into pot and coke and knew the hottest clubs and the most powerful people in Europe—my kinda girl.

For the next month we lived the good life with Karen in the little fishing village—one of “the pearls on the French Riviera,” as people called Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. It was my first time in France and I loved walking along the cobblestoned streets and bartering with the butcher, the fishmonger, the fromagerie guy, and the florist. Soon I knew everyone in the outdoor markets and cafés.

Every morning before the girls woke up, I’d walk to the boat docks at 5 AM and sit with “Frenchie,” the owner of a little café. He’d be drinking wine with his two red poodles at his side and arguing about politics and soccer with his friend Pierre, a French-Lebanese arms dealer who sold contraband weapons to the Arabs. Pierre had a 110-foot Ferretti yacht in the marina worth $9 million and guys on deck guarding it with machine guns. He was a real bad dude, but no one bothered him about it because he was so rich. That’s what money can buy you, the freedom to do whatever bad thing you want and people will still suck your dick in Macy’s window.

He was just the kind of guy I was looking for to help me liqui-date my diamonds and the twenty-five Rolex watches I’d brought with me. Frenchie made us omelets and brought us wine and cheese, and we argued and laughed and I gave him jewels and watches for money. Karen also had a jewelry contact a twenty-minute drive away in Monaco that I made use of.

In Monaco, we’d visit Karen’s friend and the heir to a famous hotel fortune who also had a villa overlooking the sea. We’d speed around in his new Bentley on the Circuit de Monaco, a street-racing circuit laid out on the streets of Monte Carlo, where the Formula One Monaco Grand Prix had been just a few weeks earlier. We raced while smoking joints and doing coke; how I’m still alive, I have no idea.

But I figured those weeks were my last taste of excess and freedom for a long time, maybe forever, so I lived them to the hilt. My days were numbered. Soon I’d have to go back to Jersey and when I did, I’d go to prison or get whacked by the mob to shut me up. This time, they wouldn’t miss.

On July Fourth weekend, Kate and I went on the run again—to London. We rented a three-floor apartment behind Harrods and spent another month living it up, until the day Lauren’s voice jolted me once again, ripping my heart to shreds.

It was mid-August and her fifteenth birthday was coming up, and she desperately wanted me to be there, especially since I’d missed the last one. But there was more. The FBI went after Debbie for the money I took and seized their house and Debbie’s bank accounts.

“Daddy, everything’s gone,” Lauren cried on one of our phone calls. “We’re in a little apartment. I want to see you! Please come home!”

Tina once called Lauren my protector; maybe she was my conscience, too.

Fuck. I hung up the phone and agonized about what to do. I’d rather be in prison or dead than to have Lauren suffer that much.

I called my lawyer.

“Make a deal with the government,” I told him. “Tell them I want to come in and talk. I’ll turn myself in.”

We arranged for me to fly into Miami at the start of Labor Day weekend and get picked up by federal agents at the airport there. My lawyer gave them my flight number and I gave Kate the kiss-off, telling her that I’d be in touch soon. We both knew that was a lie.

I didn’t fly into Miami. Instead, I flew home. I boarded a plane with those same three socks stuffed in my crotch, but significantly reduced. In September 1992 I returned to my parents’ street in a silver limo and showed up at their door unexpectedly. My mother threw her arms around me and cried, and my father glared at me as the driver unloaded my luggage into the garage.

“You lost everything, stupid! You disgraced the family name,” was the first thing he said to me. He looked older and tired, and so did my mother. I ignored his words.

“Dad, I need to hide out here for a little while until my lawyer makes a deal with the government.”

My mother looked at him pleadingly.

“You’re not going to be here very long,” he said. “Everyone’s looking for you. You’re going to jail for the rest of your life. You’re a thief and a mob guy. Like I always predicted, you amounted to nothing.”

My parents in their later years

I put my suitcases in the basement next to the accounting/cocaine-smashing table and called my lawyer to let him know I was there. I slept that night in the basement, but barely slept at all. I was trying to make a plan. First on my list was to go see Lauren. Then I had to deal with the FBI.

The next morning bright and early, they found me first. My mother picked up the phone during breakfast and I could hear the serious voice on the other end.

“Hello, is Tom Giacomaro there?”

“No.”

I almost laughed out loud. While I was gone, she’d turned into a well-trained Mafia mother.

“Look, we know he’s there,” said the voice, insistent. “This is Harry Mount from the FBI.”

I motioned to her to give me the phone. It was time. I got on the line and introduced myself.

“Hi, Tom, this is Harry Mount from the FBI.”

“Oh yeah? How do I know you’re really the FBI?” I was going to bust this guy’s balls from the get-go.

“Because, Tom, the FBI doesn’t lie.”

“Oh, I didn’t know that. That’s beautiful.”

“Tom, you have yourself a nice holiday weekend. I’ll be at your mother’s door ringing the bell Monday morning to pick you up and bring you in.”

“Yeah, well . . . Harry? I’ll be wanting to see your badge before I get into that boring, unmarked car of yours.”

He laughed. “I’ll have it ready.”

I had the FBI guy laughing already. That was a good sign, I thought, as I hung up. Already things were looking up.