On the driveway I lined up my symbols of success: Rolls-Royces, Bentleys, Mercedes-Benzes, Ferraris, and a new addition—a big black Hummer.

Everything was gold.

The interior of our new 8,000-square-foot house on Fox Hedge Road in Saddle River was bathed in $500,000 worth of twenty-four-carat gold-leaf paint on the moldings, in the wallpaper, and running up and down the spiral staircases. Even the carpet was gold. It was like living inside a fucking jewelry box.

I had ten people on staff—nannies, housekeepers, groundskeepers, and an official shoe wiper who handed visitors a pair of hospital booties to wear after taking their shoes to be cleaned and buffed. I had someone to do every little thing for us, except move the kitchen utensils, dishes, appliances, and expensive chef knives from our previous house. I personally hand-wrapped those and drove them to the new kitchen, where I carefully unwrapped and put them away in the organized way I required. None of my kids ever did a chore in their lives, not like me having to make my bed like a Marine. I gave the staff walkie-talkies so I could reach them immediately if I saw anything amiss. This wasn’t a house; it was a gilded compound.

I had a putting green in the front yard and a 70,000-gallon swimming pool, more like a lake, in the back, filled with New York State spring well water and industrial-strength heaters to keep the temperature at ninety degrees Fahrenheit in December. Next to it was a pond filled with twelve Japanese koi at $3,000 per fish. On the driveway I lined up my symbols of success: Rolls-Royces, Bentleys, Mercedes-Benzes, Ferraris, and a new addition—a big black Hummer. Inside the perimeter of the wrought-iron fence that circled the five-acre lot, I ordered a tulip to be planted every three inches—exactly.

The backyard pond in Saddle River: $3,000 per fish

Then I bought the mansion next door, and then the one across the street—recently seized from a Colombian drug lord—and paid for both in cash. After that, I bought a mansion in Delray Beach in Florida. I just kept buying and buying, the bigger the shinier the more expensive, the better. Big Nick (whom I paid in full for his house six months after we shook on it) took care of all our house renovations, skimming a few million off the top for himself, as expected—as any mob guy would.

Baby Stephanie, my third with Dorian, was born in January of 1999 soon after we moved in, and I asked Big Nick to be godfather. That spring, 45,000 red and yellow tulips bloomed around us. Who knew garbage could smell so sweet?

Oh yeah, I was back. Again. Bigger, crazier, and richer than before. My need for other people’s money was my sickness; stealing it was my cure.

Thanks to $200 million of investor money and Allied Waste deal money, my checkbook balance on an average day was anywhere from $600 to $800 million. Seeing those numbers in my bankbook made me feverish—I needed to spend it. So what if I was using other people’s money or money I didn’t have yet to bankroll my lavish life of luxury—I’d pay everyone back when the money came in later that year. Of course I would.

“Who makes all the money, Rob?” I’d ask my assistant.

“You do, Boss!”

“And who spends all the money, Rob?”

“You do, Boss!”

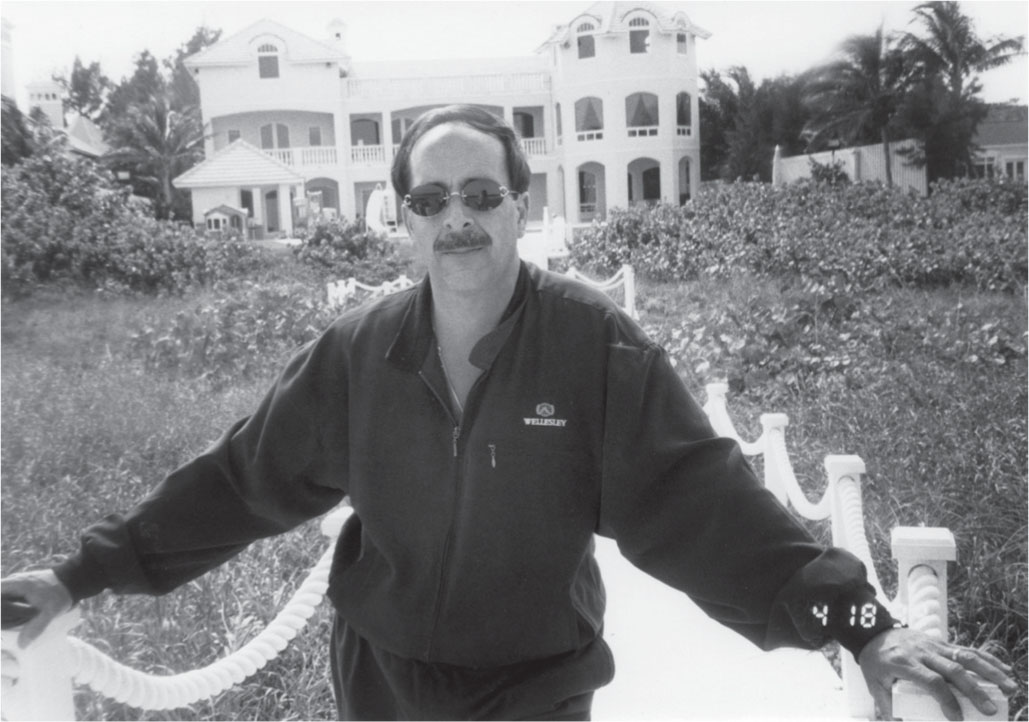

Wearing my Wellesley jacket at the mansion in Delray Beach, Florida

![]()

Damn right. I moved Wellesley out of the funeral home and into a $5 million, 87,000-square-foot office in Montvale, where my weekly cost for upkeep was $1.2 million. I hired 160 new employees in the first three months and fed them well.

Every day I gave my staff free breakfast, lunch, and dinner from the gourmet kitchen. Fridays were extra special—that was “Mob Day” at Wellesley, inspired by Mr. Alex and his Friday “Police Day” lunches. On those days, I arrived at the office at 1 AM wearing my monogrammed TJG chef outfit and met Freddy there to open up the kitchen. The crew arrived close behind with the goods—tomatoes, corn on the cob, ground sirloin, basil, sausages, garlic, peppers, onions, fresh pasta, filet mignon, prime rib, turkey breasts—and we’d start chopping, peeling, marinating, simmering, and seasoning. Fat Pauly and The Nickys would arrive around 6 AM with fresh mozzarella and thirty loaves of Italian bread fresh from the oven and start on the pizzas. I had four Bakers Pride pizza ovens brought in special from the Bronx. Cooking dinner, whether it was on Sundays at home or Fridays at the office, was one of the few moments I felt a sense of family happiness—a leftover from my childhood.

Wayne, my newest muscle-bound driver-bodyguard, drank coffee and stood guard as we worked. A former Newark cop, Wayne was my kinda nuts and had a temper, a good combination for a bodyguard but not so much for a sous-chef. The one time I asked him to stir the sauce he told me to go fuck myself. Say it a second time, and I’d be forced to kill you with my best Suisin high-carbon-steel Japanese Gyutou chef ’s knife. And that would be a waste of a good knife.

By 10 AM, as the tables were being set to seat 150, I went out to the parking lot to inspect the company cars. I had an outside service come in once a week in panel vans to hand-wash them—thirty BMWs, thirty Mercedes-Benzes, thirty Lexuses, and ten Lincolns.

At noon, before we served, my kitchen help and I started on the Grey Goose vodka before the staff, cops, and mob guys arrived to eat—they came in from Staten Island, Brooklyn, NYC, and Connecticut.

The final touch was to outfit my guys in white chef jackets for serving. A few more shots of Grey Goose and we put on Sinatra over the sound system. The setup was spectacular.

By 3 PM everybody was stuffed and ripped-up drunk. The cafeteria turned into a social club with all different factions of the Gambinos, Genovese, and Colombos—many of them packing guns—playing poker and blackjack. The music turned from Sinatra to disco, and the pretty receptionists from upstairs danced on the tables. On a Friday afternoon, it was the party of the week to be at.

And you know who else was there on the sidelines, quietly watching the mob guys play poker and the pretty girls dance? Our Harry.

As soon as he retired from the FBI, he got permission to join me at Wellesley as my Director of Security and Human Resources, with a starting salary of $150,000 and a brand-new Porsche Boxster, as promised.

At first glance, his job was to protect my crew and me.

He set up an off-duty, plain-clothes police officer to sit in the Wellesley lobby from 6 AM until I left the building at night. He installed closed-circuit TVs throughout the building and watched everyone who came and went on monitors in his office down the hall from mine, making sure no strangers approached me. I was a “high-security risk,” he reminded me, because of all the enemies I’d made, past and present. That garbage guy we threw down the fire escape at Valentino’s, for example, was one of many who didn’t have warm, fuzzy feelings for me.

“I’m sure a lot of people want you dead,” Harry said. He beefed up my security at home, installing a camera system and hiring two off-duty cops—one a lieutenant—to man the two front gates twenty-four hours a day and a third to sit in an unmarked car in front of the house. Anybody arriving for a business meeting was scanned with a metal detector to check for guns or knives before stepping in.

On the human resources side, Harry vetted and did background checks on the hundreds of job applications coming in. I was hiring twenty new employees a week to build up the accounting, due diligence, and legal departments in preparation for all the garbage deals to come in the year. I hired a lot of people to populate my chessboard; everybody had something I’d need and use at some point, even though I wasn’t sure when I hired them what that something would be.

Harry worked harder for me than he ever did for the FBI, he said. But it seemed to agree with him.

In late spring I threw a Hawaiian luau for three hundred in my backyard, complete with a twenty-one-piece band, propane tanks cooking Lomi Lomi salmon and kalua pork, waiters in white gloves, and a whole lotta poi and leis, all going on under a big tent. I was standing with The Nickys drinking vodka when we saw Harry arrive. After parking his Porsche out front, he came around back and was ordering a scotch at the bar when we spotted him, looking sharp.

“Get a load of the highfalutin Fed over there, banging down scotches,” Big Nick said, with a smirk.

“Yeah, he’s traded in his JCPenney rags for Bloomingdale’s,” I said. We watched Harry hang a lei around his neck and mingle with the crowd.

The pool in Saddle River in progress

“Now there’s a guy who was suppressed for twenty years working for the government,” Big Nick said.

“And now he’s wit us,” said Nicky Glasses.

“See what you done to this guy, Tommy?” Big Nick said. “He always wanted to be bad and you brought it out in him. You ruined him. You turned him out like making a nice girl into a whore.”

To me, Harry never looked more beautiful.

![]()

Because having a former FBI agent on my payroll gave Wellesley rock-solid credibility and looked so good in our portfolio, investors flocked to us. That was the real reason I wanted him. If this FBI guy’s on board, Giacomaro must be clean and legit! They opened their wallets. The more money they gave, the more I spent—on house renovations and expanding the office.

Having Harry on staff also meant he’d continue running interference for me with the US Attorney’s Office. Every few months he’d get that call. Lately, it was from Joe Sierra.

“Jesus, Harry. I got another call from the judge today. He says it’s time to sentence Giacomaro.”

“Nah, not yet,” Harry would say. “He’s still giving us information.”

I had it made. An FBI guy in my pocket, money flowing like Niagara Falls, and my cousin Anthony hidden away in his office laundering it for me—we had more than 117 bank accounts at Wellesley and at least fifty of them were out of the country. I was so bigheaded and self-important about who I was and what I could do, I thought I was invincible. And I was, for a very long time.

Until it all came crashing down.

After the simultaneous deal in December, we continued to close them in groups of fifteen in the same way, at that same hotel, until March. That’s when I helped broker a massive deal for Allied Waste in which they bought the Houston-based waste and disposal company Browning-Ferris Industries (BFI). It was an unusual “reverse merger” because BFI was the bigger company, doing $4 billion a year, while Allied only did $1.7 billion. But I knew a way to get it done, and the move made Allied Waste the second largest company of its kind, giving it annual revenues of more than $5 billion and assets of close to $14 billion—they were instantaneously gigantic, and it was because of me.

So it didn’t make sense when my deals with Allied slowed down after that. By July, the president of Allied wasn’t returning my calls. In August, after they fully merged with BFI, I finally got him on the phone. Now that they’d gotten so big, he explained, they didn’t need my hundred garbage companies anymore.

“We’re reneging on the deal,” he said.

“What? That’s a breach of contract!” I yelled. I actually said those words. Me, the guy who never fucked anyone over, never.

“You’re leaving me no choice but to sue you,” I said.

Although Allied Waste was a legitimate, publicly listed New York Stock Exchange company, behind the scenes they were also mob linked and had no problem playing dirty. Problem was, I couldn’t just send The Nickys over to beat them up as I normally would. With my sentencing looming precariously, any attention to me would raise a red flag and could get me in the kind of trouble Harry might not be able to fix.

“If you sue us,” the president continued, “you’ll be showing up in court in shackles.”

My hands were tied.

Losing that deal left me with my dick in my hands and up my ass, totally fucked. I owed investors well over $250 million and they had to be paid yesterday, but I’d already spent their money. I went to see Joe Sierra at the US Attorney’s Office to explain.

“I got a problem,” I told him. “They broke the contract.”

“Well you better figure it the fuck out,” he told me. “You did this to yourself, you’ve got to undo it. You’re smart—think of something. Diversify.”

![]()

And that’s how I got back into trucking. Even though Harry had told me not to, a massive trucking deal could get me out of my mess; I was sure of it. I knew the industry and I knew the guys.

Big Nick knew the owners of the largest trucking company in the Garment District, Dynamic Delivery Corp, because it was Gambino owned.

“I want to buy it,” I told him. There was no time to waste. “Get me a meeting.” He made a few calls and days later a black Mercedes arrived at Wellesley carrying Tommy Gambino Jr., the son of Tommy Gambino Sr.—owner of Dynamic Delivery Corp and longtime capo of the Gambino crime family.

My managing director, Mario Sisco, got to work wooing the Gambinos in a series of meetings, while I researched and came up with another one of my never-been-done-before brilliant ideas.

Overnight Transportation was a nonunion trucking company based in Richmond, Virginia, that did a billion dollars a year business. They spent $100 million per year to keep the union out of their business while the Teamsters spent $100 million a year trying to unionize them. What if, I thought, I got the Teamsters to lend me the $100 million they would have spent anyway and I would take that money and leverage it into $300 million and with that, buy Overnight Transportation and unionize it. That way, the Teamsters would add tens of thousands to their membership and I’d have money to pay back my investors. It could work. And there was only one person who could help me make it happen—someone irrevocably linked to my past by way of his father.

![]()

I sent Mario Sisco to Detroit to meet with Jimmy Hoffa Jr., who had taken over as Teamster president a year earlier and already had the reputation as a leader who wanted to build and unite the union. That summer of 1999 he held solidarity rallies and created 2,000 full-time jobs for his union members. He also met with a team of investigators and lawyers to form an official probe, manned by former FBI agents, to stamp out the mob’s influence on and infiltration of the Teamsters.

I didn’t let that stop me. His father and I went way back; he was the reason I was there.

Mario met Hoffa Jr. at a hotel in Detroit to pitch him my idea. From his father, he’d heard about the scrawny kid with the baseball cap who used to bring him suitcases full of money. Since then, he’d heard my name around. Hoffa Jr. loved the idea, but there was the problem of this new legal team watching over any mob influences.

“I got another idea for Tom,” he said to Mario. “The Central States Pension Fund is worth $22 billion and I can lend you $50 million from there. Then I’ll hook you up with my guy in Chicago, and he can give you the second $50 million you need.”

His guy in Chicago was the president of one of the Teamsters Union Locals, who was mobbed up with the Giancana family.

“Mario, I want those union memberships and I want to help Tom out of his mess,” he said, “but there’s one other thing I want in return.”

“Anything you say, Mr. Hoffa.”

“I got five guys in Kansas City, and I want you to put them on your payroll as consultants for two grand each,” he said.

“You got it,” Mario said, and they shook on that.

![]()

With the $100 million expected to come in, I started to quickly put together the Overnight Transportation deal, and just in time. By the end of 1999 my beleaguered investors were losing patience and the lawsuits were piling up.

The Quirks finally filed a lawsuit against me and so did a New York businessman, Michael DeBlanco, who’d complained to Joe Sierra three years earlier about me and nothing was done about it. I wasn’t worried about those two suits. I knew I’d have my money soon and could pay them.

The lawsuit that did derail me that year was one filed by Reme, one of the garbage companies in my first Allied Waste deal in December 1998. The owner of the company, Ray Esposito, was a mob guy I knew from the Bronx. He was a big guy, about four hundred pounds, and he’d become one of my best friends during the year I was putting together that deal. He loved me—loved me—like a son, even more. He’d also become one of my biggest investors in Wellesley, to the tune of $6 million. His businessman son, Neil, had invested $5 million.

After that December deal, I paid Ray the $100 million that I owed him for his company, fair and square, but Neil insisted I owed $20 million more. I had made Neil a verbal promise, he reminded me, that he was a partner in Wellesley—a promise I’d made to so many. I didn’t mean it, of course. But it was the only way I could get his father to agree to be in my deal.

Like Mr. Maislin, I demanded loyalty. But that didn’t mean I gave it myself.

I reneged on my promise and Neil sued me in federal court in Hartford, Connecticut. Harry was trying to get me out of it, but the Espositos were a prominent family in Connecticut and my FBI guys had less pull there.

Plus, Neil was sneaky. He had friends who worked at Wellesley and got them to sift through my garbage and piece together shredded documents to build a case against me—confidential papers about bank wires and movements of large blocks of money. His lawyers used them to convince a federal judge in Hartford to order an injunction against me to stop all Wellesley activity, and they put a monitor on the company.

I wanted to break the guy’s fucking neck.

I went up to Connecticut to meet with Ray to discuss the situation.

“Ray, your son is jeopardizing my future acquisitions here in Connecticut,” I told him. How was I supposed to pay back investors if I couldn’t work?

“I don’t know what to do, Tom,” Ray said. “I can’t control him.”

“Tell him that if he doesn’t get off my back, there’s gonna be a problem.”

Two weeks later on the night before Halloween, Neil was hosting a grand opening party at the new Henri Bendel boutique he’d just bought in Hartford. I sent The Nickys to make him sweat. They showed up looking like two goons on a casting call for The Sopranos—which had premiered on TV that year and was a big hit with my crew—and plopped a case of Cristal champagne at Neil’s feet.

“Tom Giacomaro wanted you to have this,” one Nicky said. Neil’s face went white. The Nickys hung around for a while, long enough to make him so nervous that he drank too much booze and did too much coke. But they were long gone by the time Neil hopped into his silver Mercedes 500SL (with a black interior) with his girlfriend and sped home. As he took an exit off the highway, he lost control of the car and went off the road into the woods, hitting several trees before overturning. Neil went flying through the sunroof and ended up in little pieces in the woods. At 4 AM my phone rang. It was Carmine Esposito, Ray’s cousin.

“Tom, Neil’s car went off the road tonight,” he said. “He’s dead.”

“What?” I was truly shocked.

“The word on the street is that you did it.”

“No, no way. I swear to you.”

And I didn’t, I really didn’t. At the same time, I couldn’t help but think: No more lawsuit!

The Connecticut State Police arrived at my gate on Fox Hedge Road early the next morning. After a lot of phone calls and pulling rank, Harry was able to convince them I had nothing to do with Neil’s death and to back off. The lawsuit disappeared.

But I don’t think Ray was ever convinced I had nothing to do with his son’s death. At the funeral, I sat at the family table and saw how he looked at me. His grief-stricken eyes said: You killed my son.

After that, the garbage companies in Connecticut started spreading the word that Wellesley was mobbed up and had financial problems, and it messed us up even more. I started working from home because there was too much heat on me.

The cocaine arrived just in time to ease the tension.

That year, Big Nick brought in his sister-in-law’s husband, businessman Eric Reichenbaum, as an investor. He’d just sold the family company (they made those Christmas tree air fresheners people hang inside their cars) and made $100 million in profit. Eric was liquid and a good “mark,” but also heavily into coke, which was not good for me. I’d been staying away from it so I could stay sharp for my business deals, but with the year I’d had, I didn’t need much encouragement to start up again.

At least once a week Eric and I drank too much and got coked up and rented a bunch of top-of-the-line hookers. Wayne set up the girls for us—their rate was $1,000 per hour—and we’d pick them up in a limo along with any other Wellesley investors who wanted to party with us.

The girls were nicknamed for the cities they grew up in—Albany, Berkeley, Chicago, and Cincinnati—Berkeley being my personal favorite. At the Plaza, an apartment/suite would be waiting for us. We’d do more coke and champagne before we each took a girl into a private bedroom.

In the morning, we’d meet for eggs Benedict in the suite’s dining room like a little family, go shopping at Bergdorf’s, then go back to the Plaza to do it all over again. My bill at the end of two days would be $150,000. If it was winter, we’d take hookers and strippers to my house and drink in the hot Jacuzzi while Dorian and the kids were away.

Fat Pauly had an office down the hall from me (next to The Nickys, who were next to Harry), and he was not so happy watching me stumble down the destructive path with Eric. He was a family man, a “good Catholic,” and well respected in the community. And as of late, he’d become my consigliere of sorts.

“You’ve got to calm down,” he’d say to me, after I’d drag myself into the office following two days of boozing and coke with the hookers. “This behavior is going to lead to disaster.”

Several times over the next few months, Fat Pauly would find himself at the Plaza, banging on the door of my suite because I hadn’t shown up for work.

I was spinning out of control again like I’d done years before. Even The Nickys were appalled at my behavior. As a rule, mob guys didn’t get involved with hookers or drugs, but I convinced The Nickys to come to a strip club with me around that time. I was so fucked up that night that I let a stripper suck my dick right there in the strip club in front of them, in front of everyone.

“You’re fucking repulsive, Tom!” said Nicky Glasses. “Look what you’re doing! What the fuck is wrong with you?”

He was so disgusted that he got up and left. I zipped up my pants and put my head in my hands. I didn’t know how to explain to them what was happening to me. I didn’t know how to tell them I was panicked that I wouldn’t be able to fix the mess I’d put myself in this time.

That New Year’s Eve, I stayed home with Dorian and the kids as we entered a new millennium. Every tree and shrub and the swimming pool were lit up with white lights; it was so bright it looked like daylight.

My mother came over to sit through midnight with us because she was paranoid the world would be plunged into chaos. She was caught up in the Y2K mass hysteria that everything was going to crash, and computers and clocks would go haywire, so she withdrew all her money from the bank and stored cans of food and bottles of water in the basement. She arrived at the house with a Bible.

On TV, we switched channels back and forth between the crowds in Times Square wearing funny hats, and the news that Boris Yeltsin had resigned that day and Vladimir Putin, a longtime KGB foreign intelligence officer, was the new president of Russia. He was a corrupt killer, an enemy of our country, and my mother shuddered when his face appeared on the screen.

As the clock struck twelve, my mother clutched her Bible closer to her chest and braced herself for doom and the impending apocalypse.

“I have a feeling,” she said, shivering, “that something terrible is about to happen.”