The room had a cement slab to sleep on with four posts on it, in case they needed to chain you down.

They try to break you in prison.

They try to destroy your mind until your sense of self shatters into a billion pieces. If you’re especially obstinate, they give you a dose of what they call “Diesel Therapy.”

It goes like this: For a month they move you from prison to prison every two or three days—pulling you from sleep in the middle of the night or pulling you off the toilet when there’s still shit coming out of your asshole; they don’t care. The goal is to keep you moving and never let you feel settled in any one place.

They stick you in a holding area before they move you, and all you have is the orange jumpsuit you’re wearing; you can’t even take a toothbrush. You’re a number, not a person—you don’t own anything. Then they shackle you and put you on a bus, chaining you together with a dozen others like animals, and drive you for five hours, seven hours, eight hours; you can’t be sure how long and don’t know where you’re headed.

No food or water. Two guards stand watch in the bus with shotguns. The toilet is in a little cage out in the open but most guys end up pissing and shitting themselves before they can get to it.

When you arrive at your new temporary prison, you’re thrown into another holding area. You’d be lucky if, at that point, they toss you a moldy cheese sandwich. After a few hours, the correctional officers (COs) take you to a new cell or bunk that you’re sharing with a 6′6″ savage named Bubba, whom you’ve just woken up and he’s really mad. He wants to kill you. He probably has a shiv under his dirty blanket. I learned early how to handle guys like Bubba:

“Listen, you fat motherfucker,” I’d say right away, giving them a crazy-eyed look as soon as the officer left.

“Maybe your arms are as big as my legs. But don’t fuck with me. Because eventually you’ll fall asleep, see, but I never sleep. And you’ll wake up with me on top of you biting your ears and nose off, biting your entire face off. So leave me the fuck alone.”

“You’re the craziest white guy I’ve ever met in my life,” they’d say.

I got the nickname “the Italian Hannibal Lecter” without ever having to actually chew off someone’s body part. They were scared of me, and that kept me safe.

![]()

But let me back up a bit.

Three weeks after that New Jersey Star-Ledger article was published, terrorists flew planes into the World Trade Center.

It was exactly thirty years earlier that I made secret money deliveries for Mr. Alex there, while the towers were being built. My career was on the rise as those towers went up, and my world collapsed as those towers fell down. Years later, Tina would describe the fall of the Wellesley empire very much like the tragedy across the river: “There were so many dead bodies,” she said, “it was catastrophic.”

The news article in the Star-Ledger that August was instigated by several of my beleaguered investors and scorned partners, including the Quirks, who got zero help or results after trying to sue me and after reporting me to the FBI. So they went to the press.

The story detailed everything—my looting and bankrupting of the trucking industry, the lawsuits against me, the millions I stole from Wellesley, the questionable ethics of the FBI and US Attorney’s Office, the pension fund, Cambridge, Allied Waste, and more. It named names—Camino, Kapralos, Barnetas, Frankie Cam, David Lardier, Michael DeBlanco, Michael Chertoff, and Keith Moody.

The reporter called me a “con man” and “quintessential salesman” who “used Wellesley bank accounts as a personal slush fund to pay his family’s prodigious bills, from lawn care to electric service to the $87,000-per-month mortgage on a Bergen County property . . .”

On the way to court, January 14, 2002

Photo by Aris Economopoulos/The Star-Ledger

Not only was I in hot water but so was the US Attorney’s Office and the FBI—who were bombarded with furious calls from Washington: What do you mean he was on the docket for six years and you didn’t sentence him? What do you mean he was scamming and looting while working as our informant? What do you mean Harry Mount now works for him?

Joe Sierra was immediately asked to resign and so were a few others. In a hasty attempt to do damage control and save face in front of the public, Judge Wolin quickly set my long-awaited sentencing date.

“Giacomaro is going to get fried for this,” he told my attorney, Cathy Waldor, in chambers before my sentencing. “I’ve had hundreds of calls about him from people insisting we open up a new investigation, which we are. I knew all along that he was just playing us. The government let this happen,” the judge told Cathy, “not me.”

No one wanted to take any blame, but they were all willing players in my con game—all of them.

![]()

In January 2002 Judge Wolin sentenced me to eighteen months for the embezzlement of $1.2 million from the Majestic Carrier pension fund, the sentencing I’d been ducking for ten years. It didn’t matter that I’d already paid the money back (thanks to Harry’s urging).

Three days after my sentencing, Mary Higgins Clark—who still held a mortgage on my Saddle River home—gave an interview to the New York Post about my con artistry: “I was shocked,” she said. “Shocked is the only way you can describe it. I may have a great imagination, but I never could have invented [Giacomaro].”

I took that as a compliment.

I started my prison term at the end of February at Fort Dix camp in Jersey. Camps were the lowest security you could get in a prison—it was a sissy-la-la camp full of white-collar criminals and kids caught with pot. It had little “out of bounds” signs around the perimeter, and you could come and go from your unit all day long, twenty-four hours a day.

Still, it was a shock to my senses. I went from sleeping in a $25,000 canopy bed to sleeping on a dirty mattress in a metal bunk bed. From dining on filet mignon and champagne to white rice with soy sauce, which I had to stand in line for hours in the cold and snow to get. From wearing $2,000 Canali suits and Bruno Magli alligator shoes to prison khakis and ten-dollar boots with steel toes. From having maids to clean every speck of dust to me mopping the barrack floors.

I had no idea how to do jail. I was in complete denial and pissed off and had no intention of adapting. I refused every program offered to me on how to “better” myself and wouldn’t look at the TV or read newspapers because I didn’t want a reminder of the real world. It made my new reality too impossible to endure. Besides, why do I need to change? It’s only eighteen months, I kept telling myself. As long as I don’t fuck up I’m out in six!

The sleeping quarters at Fort Dix were like military barracks, a giant room with bunk beds lined up against the walls. I had my own locker near the bed, which I kept perfectly organized. I made my bed until it was coin-toss Marine tight. I washed my hands on the hour in the dirty communal bathroom. Every morning, I borrowed an iron and ironing board from the COs so I could press my cheap, used, stained khaki uniform and crease the sleeves and slacks. With commissary money that my mother deposited every month for me, I was able to buy some extras like pasta, sweat pants, socks, a pair of sneakers, and instant ramen noodle soup that everybody called “crackhead” soup because at ten cents a cup, it was the cheapest item at the commissary.

Three days after I arrived at Fort Dix, I got a collect call from Dorian. Before going in I’d found a way to secretly leverage $25 million to her so she could take care of herself and the kids while I was gone, but it wasn’t enough to keep them.

“You just lost your beautiful wife and your beautiful family,” she said. “I’m divorcing you.” Click.

Lauren and my mother were the only two who visited me the first few months, coming together every Saturday. Lauren was comforted to learn that I’d probably be home for Christmas, and we tried to cheer up my mother, who was skinnier and more nervous than ever, with that. Now that Dorian and the kids had left me, I wasn’t sure where I’d be.

“With me, Dad,” Lauren said, giving me a reassuring hug.

But as the days and weeks went by, I was less reassured.

In April and May 2002, the New Jersey Star-Ledger published two follow-up features on me:

EXTRAVAGANCE GONE UNCHECKED

THE MAN WHO STOLE $80 MILLION WHILE WORKING FOR THE FBI

One afternoon at that time when I called my mother from the prison pay phone, she sounded frightened.

“There are people here. A lot of people.”

It took some time to figure out what she was trying to tell me; the FBI was there and they were searching the house and taking everything.

“Ma, did they go downstairs?”

They did. And when they opened the air-conditioning ducts in the ceiling, they got hit in the head with my falling suitcase filled with a million bucks.

![]()

One by one, and quickly, I lost everybody.

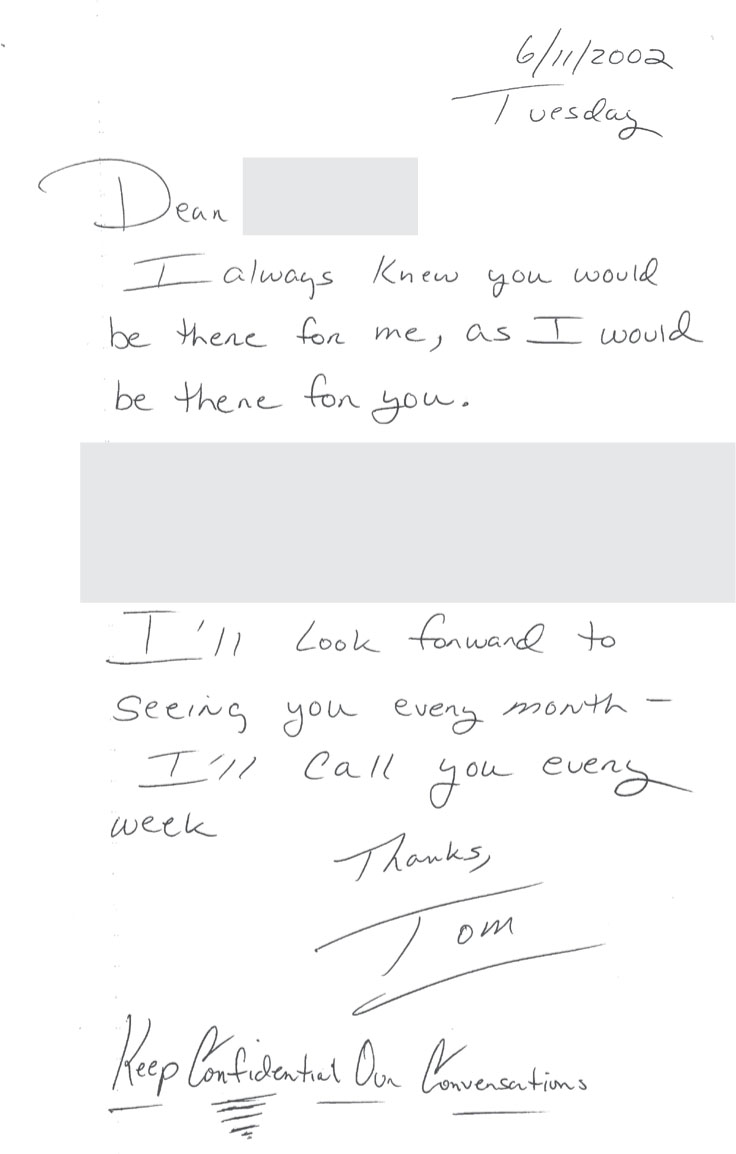

Everyone I knew except Fat Pauly stopped taking my calls—advised by their lawyers to have no contact with me. I mailed Fat Pauly a note of gratitude; he was all I had left:

June 11, 2002

Dear Pauly,

I always knew you would be there for me, as I would be there for you.

I’ll look forward to seeing you every month—I’ll call you every week.

Thanks, Tom

Writing to Fat Pauly from prison

But soon after, even Fat Pauly had to go. He came to visit me the third week of June and told me his attorneys had said the same. Sitting on the plastic chairs in the visiting room, he also gave me a warning:

“A few of the guys worry they’re targets in the investigation on you because they haven’t been spoken to yet,” he said. “They said to tell you that you better keep your mouth shut.”

“Who told you to say that?”

“It doesn’t matter who.” He cleared his throat and looked away, then met my eyes with worry. He was scared. “They said to remind you that your daughter and your mother are still out on the street so you better be careful.”

Fat Pauly and I both knew it was a real threat. I was being reminded to follow omertà, or else.

Lauren visited a few weeks later by herself on July 3rd. She was bubbly and pretty in her pink jogging outfit, excited that my mother had bought her a new Chevy Blazer from money she’d taken from the basement suitcase before the Feds got it.

“But baby,” I said sadly, “they’re probably going to take away the townhouse I bought you.” It was a gorgeous half-million-dollar townhouse she was sharing with her best friend.

“It’s okay, Dad.” She smiled. “I’m going to move in with grandma. Don’t feel bad.”

I thought about Fat Pauly’s warning and told her to be careful on the roads with the holiday drivers. She and her best friend were going out that night to celebrate Memorial Day. And for the first time since the article came out and I fucked up my world and hers, I apologized to her about what I’d done.

“I’m sorry,” I told her. “I’m sorry for being so stupid and for letting this happen to us.”

“Don’t worry, Dad,” she said. “Everything will be back to normal at Christmas, after you get out.”

We made plans to see each other the following week and hugged goodbye.

The next afternoon I was in my barracks readying for four o’clock count when a CO ordered me to report to the counselor’s office. I walked in to find a group of people waiting for me: two counselors, Dr. Baruch and Dr. Jennifer Bowe; my case manager; Aziz, the chaplain; two or three cops; and the warden, an older Italian guy who liked me. He had tears in his eyes.

“We’ve got bad news for you, Tom,” Chaplain Aziz said. Jennifer took my hand.

“What? Oh, no. My mother?”

“No,” said Aziz, “it’s your daughter. Tom, Lauren was killed last night.”

My knees buckled and everything went dark.

“There was a car accident,” he continued, as Jennifer and a few others tried to catch me as I fell. “She was in the car with her friend and they were driving home. Her car veered off the road and no one knows why. They both died.”

No! No, no, no, no! Not Lauren! Of all people, not her!

“Tom, your ex-wife Debbie is on the phone,” someone said, as they put the receiver to my ear.

By now I was lying on the filthy prison floor, catatonic.

“Tom? Oh, Tom!” said Debbie’s voice from far away. “We lost our baby!”

![]()

They let me go to the funeral for a few hours, which was against usual protocol.

It was the same church in which Debbie and I got married. The place was loaded with kids, all of Lauren’s friends. My only friends to show up were Fat Pauly and Ray Esposito. Everyone else was too afraid to come. Lauren’s face was so destroyed in the accident, the casket stayed closed. Nicky, Tommy Jr., and I held hands and followed the casket out of the church. Everybody has something that will break their spirit, and for my family, this was it.

After the funeral my mother doubled down on her drinking, as if she wanted to kill herself that way, and I sunk into depression. I’m being punished, I thought. I was too greedy. I wanted too much, I had too much, and then I lost the only truly precious thing I had. I was so distraught that the old Italian warden who liked me decided to let me out early to finish the last few months of my sentence in a halfway house.

When that day arrived, my mother was waiting for me outside the prison gates with a car and driver. But apparently my situational awareness had gone to shit because I didn’t notice the cops and FBI agents hovering nearby. I walked toward the car and when I was fifty feet away, they surrounded me in golf carts. One of them was the US postal inspector and another was FBI agent Dennis Richards.

“You’re not going nowhere,” said Richards. “Your halfway house is canceled.”

Richards had been with the FBI for thirty-five years, he told me as they handcuffed me and took me back into the prison.

“And you’re gonna be my last case. You know why? Because there’s nothing more prestigious than the FBI, and yet you went out and gave us a bad name and disgraced us.”

Richards was in charge of the new investigation on me and he had news for me:

“You’re in a lot of trouble,” he said. “You’re going to be under indictment again and face new federal charges. So, you better think about how to help yourself and start talking. We’ll be back in a few weeks to see you again.”

![]()

In December 1992 I’d served two-thirds of my sentence and they took me out of sissy-la-la camp and sent me across the street “behind the wire” to the low-security prison. Here, I was in a confined area and locked down. Every hour we had “the five-minute move” when you were allowed to go from one location to the next—the laundry room, medical, the commissary, or the chapel—they were all separate buildings or units. It was like playing musical chairs but when the music stopped, if you didn’t have a chair, the doors locked and you either got shot or put in the hole.

Instead of “out of bounds” signs, the prison was surrounded by a double fence with quadruple barbed wire and trucks that drove around the perimeter day and night, carrying guys with shotguns and machine guns.

Everybody had to have a job so I got one at the chapel—Chaplain Aziz felt bad for me after Lauren’s death so he gave me an easy job as his clerk, looking after the books and accounting. Wonder what my father would have thought about that. He did the books for the mob and I did the books for god. At least I was able to steal paper towel from Aziz’s bathroom to hide in my locker back at the barracks. I needed it to scrub my filthy locker and dry my hands after their hourly washings.

At night, I lay in my bed and agonized over three thoughts while everyone else slept.

They plan to keep me in here for the rest of my life.

Someone killed my daughter and I am to blame.

My fucking father was right. I amounted to nothing—less than nothing.

![]()

I told the guards I was so upset about my daughter that I wanted to kill myself. I didn’t really, but I was hoping they’d be easier on me or send me back to the camp if I said that. It had the opposite effect.

I was immediately taken to the medical unit and put on suicide watch.

They took my clothes away and put me naked into a freezing, padded cell and assigned an inmate to watch me with my balls hanging out 24/7 through a little windowed slot. The inmate wrote down every move I made: “Inmate just took water.” “Inmate just pissed.” “Inmate just took a shit.” “Inmate’s lying down.”

The room had a cement slab to sleep on with four posts on it, in case they needed to chain you down. For five days, I lay on the slab as an air-conditioner blew cold air on me. It was a method of torture, like waterboarding, to snap you out of any suicidal thoughts. If I moved too much, the medical staff—who were also watching on camera—took it as a need to straitjacket or “four-poster” you, so I stayed as still as I could.

I tried to keep sane, to keep from breaking, but I was stripped bare—literally and figuratively—and afraid for the first time in a long, long time. I had no idea what was going to happen to me with this next indictment. I had no idea how strong I could be to handle prison life. I had no idea how to worm myself out of this jam.

So for the first time ever, since her death, I talked to Lauren out loud:

Honey, help me get through this. Help me stay calm and keep it together. Give me strength.

After five days of this, the medical team decided I wasn’t suicidal after all and let me out on the provision that I went on antidepressants and saw the staff shrink, something I hadn’t done since I was ten. I agreed. But I stuck the pills under my tongue and threw them out later.

Dr. Jennifer Bowe, the one who held my hand the day Chaplain Aziz told me about Lauren, was a pretty blonde. Even though I didn’t believe in therapy bullshit, seeing a pretty blonde for an hour twice a week at least gave me something to look forward to.

“You’re not eating, Tom.”

“My life is over,” I said, as I picked my fingernails with a toothpick until the cuticles bled. I’d lost fifty pounds in the six months since Lauren died. Sadness had a lot to do with it, yes. But so did their shitty food.

I had no intention of pouring out my soul to Dr. Bowe, but something about the softness of her voice and her eyes disarmed me.

“Why did I do this to myself and everyone else?” I asked her, and myself.

“Why? Why did I need a hundred Rolex watches? What was I trying to prove? I was so sure I could pay back all that money. All the Bentleys and the suits and the houses and the 45,000 tulips, what for? All gone. And yet, the one thing that was real, that was true . . .”

Dr. Bowe didn’t tell me then, but the doctors at Fort Dix had written down some answers to my questions in their reports: words and phrases like “bipolar” and “history of mania” and “acute anxiety” and “dysthymia” and “personality disorder with narcissistic and antisocial features” and “major depression disorders.”

“We’re going to work on it, Tom,” she said.

The next month I was shackled and taken into the US Attorney’s Office in Newark to discuss a potential plea deal for all the new criminal activity I’d done since my last plea deal—which was a lot, needless to say. The group in the conference room included US attorneys, FBI agents, state police, and state detectives from the fraud division. One of them was Agent Richards.

They showed me a three-ringed binder of FBI 302 forms containing all the interviews with my friends and coworkers, at least two hundred of them. The names were blackened out but I could still read them. They even interrogated our maids at Saddle River.

“There’s not one person here that hasn’t pinned everything on you,” they told me.

They wanted me to know who’d ratted me out, I knew that trick. Because now they would ask me to be a rat, too.

“Tell us about Nicky Ola, Nicky Calo, and Pauly Russo and all the money that disappeared. You wired hundreds of millions of dollars out of the country. We want to know where the money is, and we want to know everything about everybody.”

In exchange, they’d give me a five-year sentence, buy me a house, and put me in witness protection when I was out, somewhere nice with a good dry heat, like Arizona, or Colorado. Or Oklahoma.

“You’ll be just like Henry Hill in Goodfellas,” one of them said, laughing.

“Go fuck yourself,” I said, rattling my chains. “I’m not cooperating. I’m not giving you nothing.”

That shocked them. But they didn’t know I had my own ace up my sleeve to use as leverage.

“Okay tough guy, then we’re gonna hit you hard.”

“Oh, yeah?” I said. “How about we go to trial, huh? And the first thing I’ll do is talk about Harry Mount and then put him on the stand. I’ll say he knew about everything I was doing and that I thought I was acting as an informant on behalf of the government. And I’ll say he told all of youse guys everything. So fuck all of youse. Unless you have a better deal for me, I’m going to trial. If you think you look bad now, wait until I really smear you.”

I knew Harry could be indicted for conspiracy and corruption if I went to trial, and that’s the last thing the FBI wanted. Agent Richards was especially horrified at this thought, but he was still playing hardball.

“Giacomaro, you had power and you had money,” he said, fuming. “And now we’re going to take it all away from you.”

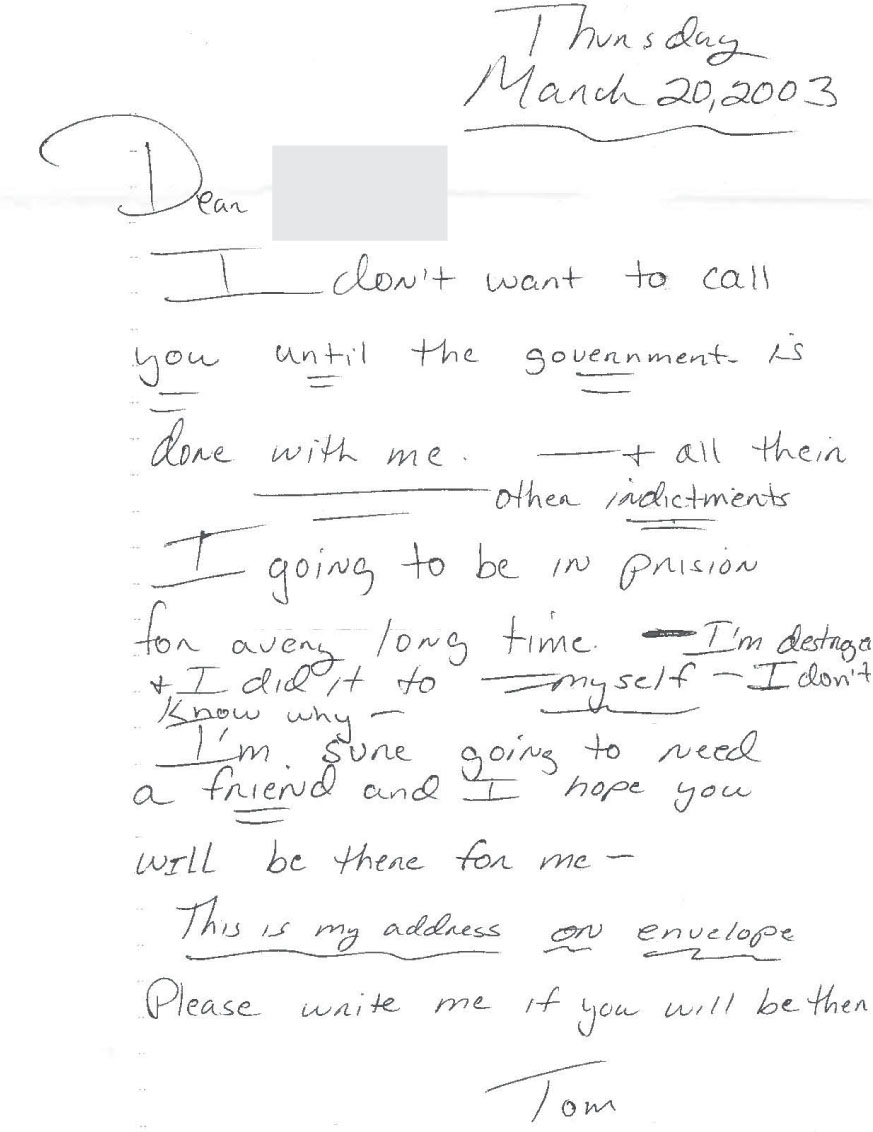

That night, in search of a friend I wrote to Fat Pauly, even if he couldn’t write me back.

Another desperate, lonely letter to Fat Pauly—my last friend

Thursday, March 20, 2003

Dear Pauly,

I don’t want to call you until this government is done with me and all their other indictments.

I’m going to be in prison for a very long time—I’m destroyed & I did it to myself—I don’t know why.

I’m sure going to need a friend and I hope you will be there for me—

This is my address on the envelope.

Please write me if you will be there.

Tom

The Feds and I met each other halfway. We struck a deal in which I didn’t have to rat, I’d get a fourteen-year sentence, and they wouldn’t indict a long list of my friends and colleagues (who had ratted on me). Also, my cousin Anthony would receive a very, very short sentence.

In exchange, I wouldn’t go to trial, and Harry and the FBI would keep their reputations and Harry would keep his pension.

Fourteen years was more time than some murderers and child molesters got. It was payback, punishment, for making the FBI look like fools. And extra time was tacked on because I was protecting my crew. I was going to do time for all of us.

(“Who does all the time, Rob?” “You do, Boss!”)

![]()

But even with our meeting of the minds, the fuckers still put me on Diesel Therapy that May, a month before I was to sign the plea agreement, just to make sure I didn’t get any ideas about changing my mind and, I’m sure, to stick it to me.

I was taken to the US penitentiary in Canaan, Pennsylvania—a maximum-security prison with electric fences and giant towers all around it. Now my neighbors were murderers, rapists, and pedophiles. It was the kind of place you had to wear boots when you went into the gated shower so that if someone comes in and tries to rape you, you can stomp and kick your way out. Maybe. Here, the biggest, meanest guys would dress up the child molesters, put ChapStick on their lips, and fuck them up the ass.

From there, they chained and bused me with thirty other inmates to a hangar at Philly International Airport and let us out in front of a row of armed guards and US marshals standing in front of a jet. It was the real-life Con Air.

They flew to Oklahoma City and kept me in a high-maximum transfer station there for two days; it was the kind of place they put psychos like the Unabomber. From there, they sent me to Michigan for a few days, then back to Philly, then back to Canaan, then back to Fort Dix in Jersey to officially get sentenced. It was all done to torment me and keep me sticking to the plan.

On June 6, 2003, FBI agents picked me up in the morning and took me to state court, where I pled guilty to money laundering. Then they took me to federal court in the afternoon to plead guilty to eighty-eight counts of mail fraud, de facto ownership, tax evasion, and much, much more. I pled in a way that would make it possible for all the Wellesley investors to get back the $69 million I took using tax credits.

“All your sentences stack up to four hundred and forty years of jail time,” one agent goaded me, “but don’t worry, you won’t get that much.”

The new US attorney for New Jersey, Chris Christie, gave an official press statement after my plea: “Unfortunately, [he] was very good at his con-artist craft,” said Christie. “The giant pyramid scheme collapsed on investors.”

Once again, I was all over the local daily newspapers. On June 7, 2003, the New York Post had these headlines:

SCAMMER MADE FBI SUCKERS

SUPER CON: FBI SNITCH ADMITS $75M SWINDLE

I wouldn’t be sentenced for another eight months so the US marshals handcuffed, chained, and transported me all over the country again. They were still trying to break me. The first prison was the barbaric Passaic County Jail, one of the worst prisons in the US.

Inside, I was waiting on a bench in the transporting area staring at the dirty floor. I was exhausted, hungry, and feeling hopeless when I felt someone standing in front of me and heard a kind, comforting voice.

“Tommy,” she said, softly.

I looked up: Tina. She was wearing a blue uniform. In the years since I’d seen my upside-down-cake girlfriend, she’d become a cop working for the Passaic County Sheriff ’s Department.

“Tina,” I said. I could barely talk.

“It’s going to be okay, Tommy.”

Passaic County was a twenty-four-hour-lockdown prison that made the others I’d been to look like the Hilton. I was put in a cell the size of a tiny bathroom and slept on a metal bed bolted to the wall. Food was a piece of meat with maggots on it slipped to you on a tray through the door. When you stepped into the showers, you stepped into people’s shit, piss, and sperm. The COs patrolled the tiers with German shepherds and if you hung your arm outside the bars, the dogs bit it off.

For the three months I was there, Tina came to my cell door every day and talked to me through a little screen.

“Are you okay, Tommy? You’re gonna be okay.”

She called my mother every day, too, to report on our meetings.

“He’s okay, Mrs. G. He’s doing okay.”

Tina told me later that she never, ever, thought I’d make it out of there sane or alive.

My sentencing in February 2004, just after my fifty-first birthday, was a spectacle.

The date, unlucky Friday the 13th, was chosen on purpose I was told, to specifically ram it up my ass. First I was taken to state court in Bergen County. The courtroom was packed with my angry victims—David Clark, Eric Reichenbaum, and others—looking like they wanted to kill me. I pled guilty to two counts of conspiracy to defraud the United States and one count of frauds and swindles. The judge sentenced me to ten years with a five-year stipulation.

“I didn’t have a Maserati!”

Photo by Christopher Barth/The Star-Ledger

“Mr. Giacomaro,” the judge asked, as she went through the documents and heard the testimony, “is there a car you didn’t have?”

My lawyer gave me a look: Don’t do it, don’t do it. But I couldn’t help myself.

“Well, your honor,” I said with a smirk, “I didn’t have a Maserati!”

The courtroom went wild and my victims flipped out.

“Strike that from the record!” the judge yelled to the court reporter. “And get him out of my courtroom! You’re despicable, Mr. Giacomaro. You’re disgusting. Get him out of here!”

A team of federal marshals escorted me out of that courtroom and took me to Newark for the next sentencing. The angry mob followed, as if they were going to witness a modern-day public hanging. Now I stood in front of Judge Wolin in my handcuffs and orange jumpsuit.

“Mr. Giacomaro, you’re back again after duping us for so many years,” he said, and turned to the group of FBI agents and US attorneys in the room, pointing at them. “And it was all of you who wanted him!”

For crimes that would normally get two to three years, Judge Wolin sentenced me to the 168 months—fourteen years—agreed upon, and said in an official press statement, “[He] is an arrogant and resistant felon.”

Four months later, Judge Wolin retired. As I said once, I was either a career maker or a career breaker. Before I went off to do my sentence, the new US Attorney Chris Christie had a final jab, as it was Friday the 13th.

“He’s an extraordinary con man,” said Christie, “but today, his luck ran out.”

I took the pinch for everyone. They led me out of the courtroom and I caught sight of David Clark as I left. His mother was the only one who came out of the whole shitstorm shining. She got her investment money back from the government, and, as I suspected, she couldn’t resist using me as fodder for her next novel.

That Christmas, Mary Higgins Clark published yet another best-selling novel: The Christmas Thief. And in a case of art imitating life, one of her lead characters was “a world-class scam artist whose offense had been to cheat trusting investors out of nearly $100 million in the seemingly legitimate company he had founded.”

The guy even looked like me: “Fifty years old, narrow-faced, with a hawk-like nose, close-set eyes, thinning brown hair, and a smile that inspired trust.”

You never can trust a writer; they’re always looking for new material. At least she was more lenient on me than Judge Wolin. Mary sentenced her fictional scam artist to four months less of a prison term than what I got.

Maybe her con man gets out early for good behavior, I sniffed. But I had no intention of behaving—or breaking.