FOOD, FAMILY, AND FRIENDS OF OURS

For a few minutes, we coulda been just a bunch of guys eating linguine on Mulberry Street.

My mother died of a broken heart on Easter Sunday in 2006, waiting for me to get out of prison. Not that we ever had such a great mother-son relationship, but we were all each other had. After a lifetime of getting beat on by her husband, then watching her only child go to prison, then seeing her first grandchild dying young in such a horrific way, she’d had enough. She drank more and more to ease the pain and fell on Good Friday, went to the hospital, then died that Sunday. I think she gave up.

With her death I lost all connection with my blood family. Uncle Anthony had died years before. My cousin Anthony Bianco, who did the books for me at Wellesley, wasn’t allowed to talk to me.

I’d been writing letters and cards to my children for years without getting a reply. When I telephoned Dorian’s or Debbie’s, my calls were either not accepted or blocked. So after my mother died, I gave up, too. I shut off what small part of my heart I had kept alive for them and started creating friends and family on the inside. You have to, to survive.

And in my case, I also met up with old friends—a lot of them.

At the beginning of 2008 I was sent to Allenwood low-security prison in Pennsylvania. It was one of the nicer ones and even got the “Best Prison in the Country” award one year. The living quarters were an open area with private cubicles with two bunk beds and lockers where you kept your stuff.

One day I was in my cubicle obsessively organizing my stuff when I heard a familiar voice behind me.

“You don’t remember me, do you?”

I turned around and nearly shit myself. It had been about seventeen years. Fucking Enzo Camino.

“Don’t worry, don’t worry,” he said, waving his hand and giving me a hug. “I know you talked to the Feds about me. But now we’re together again, and you’re gonna make up for that and help get me out. We’re family, after all.”

We were in the same unit; he was only five bunks down. There was no way the Feds and the US Attorney’s Office knew about this; it must have been a total fuckup in the system. To put me five beds down from the guy I stole with and then gave information about? Enzo had been in prison ever since Harry’s triumph in court a dozen years earlier, but he still looked great, the son of a bitch—still had that slick Tony Bennett look about him.

And now that I was living twenty feet away from him—a captive audience, so to speak—he was going to make the most of it.

He wanted out and was in the middle of yet another appeal and he had a scheme.

“I want you to concoct a story for me to use in my appeal,” he said one day, as we ate egg sandwiches on my bunk. He was bribing me with food to cooperate, and it was working. Food was the most important thing in prison because it was so hard to get, and everyone was desperate for it. After my mother died, I didn’t have anyone giving me commissary money anymore so Enzo gave me some of his, and he set up a few kitchen helpers to smuggle us a dozen egg sandwiches every few days, hidden in their clothing. Once a week, they’d bring us hamburgers. Other days, they’d bring us raw chicken pieces.

“You can say that the FBI set me up. Say the government lied and they made you lie and they trumped up the charges against me. I want you to reverse everything you said about me; I want you to recant.”

I would have admitted to anything at that point just to get those egg sandwiches and raw meat, and I did for a while. I went along with it. I signed his documents that said I lied. When I didn’t want to be pressured anymore, I knew how to get out of it quick. I wrote a letter to Chris Christie’s second in command, Assistant US Attorney Ralph Marra (who took over for Joe Sierra), and mentioned that my old buddy Enzo Camino was my new jail mate. The next day four cops showed up, handcuffed me, and got me out of that unit. No matter how bad I’d been, the government always protected their people, and as a trained informant, I was their people.

But they didn’t know what to do with me or where to put me so they stuck me in the hole. I was paired up in the same cell as a young member of the Aryan Brotherhood with a shaved head and a Nazi swastika tattooed on his forehead.

This guy was a killer. He slashed someone’s throat in chow hall and did it again to someone in the hole. Fortunately, he thought I was a character. So much so that he gave me a nickname: “Old-School.”

“Hey, Old School!” he’d say, with a punch on my shoulder. “Since you’re an old man from the olden times with an old-man hip replacement, I’m gonna have mercy on you and give you the bottom bunk.”

Everyone else was afraid of him but I wasn’t. I was used to crazy guys; I was one myself.

Stabbing someone in the neck was apparently the murder method of choice in the prison. I saw a lot of neck stabbings when I passed through the maximum-security prison in Canaan. One time when I was waiting in the holding area, an inmate stabbed another—a child molester—in the neck and threw him off the second-floor tier onto the table where I was eating dinner with a bunch of mobsters. We were eating spaghetti and meatballs when his body splatted right on the table. The sirens went off and the unit went on lockdown, but we kept eating. It ain’t so easy to make spaghetti and meatballs in a high-security prison, so we weren’t gonna waste a good meal.

Another time I was playing cards in a cell with four guys; one was scheduled to testify against John Gotti Jr. three days later. Another guy started an argument with the Gotti witness and accused him of cheating.

“I don’t think he was cheatin’,” I said. Didn’t matter.

The guy accusing him of cheating got up and stabbed the Gotti witness in the throat, over and over. The coroner later said it was ninety-two times. Then he wrapped a towel around the guy and sat him up in the bunk to let him bleed out into the towel. Me and the other guy didn’t say nothing. We gathered the cards and carefully and quickly left the jail cell.

For three days, that guy stayed there dead like that, honest to god. Every day at the counts, the cops went by to check that we were in our cells, and the stabber would stand the dead body up next to him and turn him sideways a little so they saw two bodies in there, but they didn’t notice one of them wasn’t breathing. It wasn’t until the smell of the dead body got so bad and other inmates complained that the COs realized there was a rotting body somewhere.

After Allenwood, they put me behind the wire at Loretto prison in Pennsylvania. Being at Loretto was just like being at a big mob sit-down.

My roommate for my first six months was Anthony “Fat Tony” Rabito, the consigliere of the Bonanno crime family—in for racketeering and extortion. Fat Tony and I used to walk around the track together outside to pass the time, him with his cane and me with my bad hip. He was in his mid-seventies and was a smart, funny, happy guy—even in prison. I was still fucked up about what I’d done to myself, and resistant to prison life. Fat Tony tried to give me fatherly advice.

“Look at the mess I got myself into, Anthony,” I’d say.

“Tommy, this is the life we chose,” he’d say, thumping his fist against his chest with his free hand, the way mob guys do in the movies. “We chose this mob life, you and I. You could have been a legitimate businessman, but you chose this. We can’t have regrets.”

We ate every meal together and he bought me commissary stuff. Whenever he had bags to carry, I carried them. I carried his tray in chow hall, too. I showed the proper respect for a man like him, you know? Every month I cut his hair with prison scissors, the kind little kids used in kindergarten with rounded edges and rubber tips on the ends. And I’d shave the little hairs from his ears—my grandfathers, both barbers, would have been proud.

Under Tony’s wing I had the full protection of the Bonanno crime family while I was in prison, even though I was Genovese. We talked about our families, both personally and professionally. Fat Tony didn’t have any kids and looked on me as a son. Still, I was shocked when he suggested I do the unthinkable and impossible—ditch my association with the Genovese family once I got out and become a made man in the Bonanno crime family, by his side.

“Nah, Anthony. I don’t want to get involved like that.”

“Think about it, Tommy. You’re gonna be huge again when you get out.”

Jesus. A quarter century later and they were still trying to make me. I’d stayed unmade this long, why would I change that now?

One by one, Fat Tony and I gathered more family members together at Loretto. We were in our cell one afternoon when someone knocked on our door and opened it.

“Tom! How ya doin’?”

In walked the towering Nicky Glasses to give me a bear hug and two kisses on the cheeks. The good news was that he wasn’t in the pen ’cause of me, he said. But he had to be careful about being seen with me because the association could get him in more trouble than he already was.

“Listen, Tommy. Don’t talk to me in front of everybody on the compound. I don’t want nobody to know we know each other. But you’re wit us here. We’ll make sure you’re taken care of.”

Seems I was wit all of them, once again.

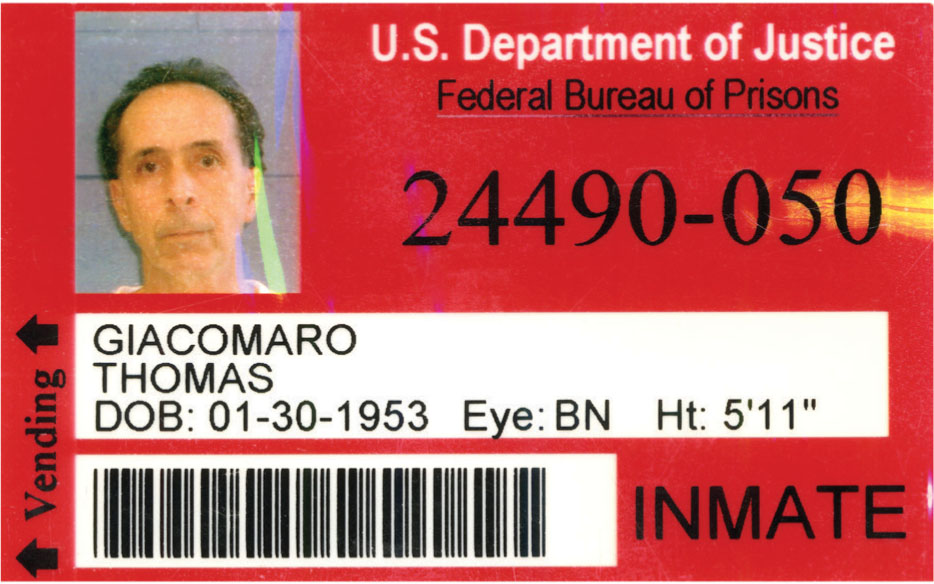

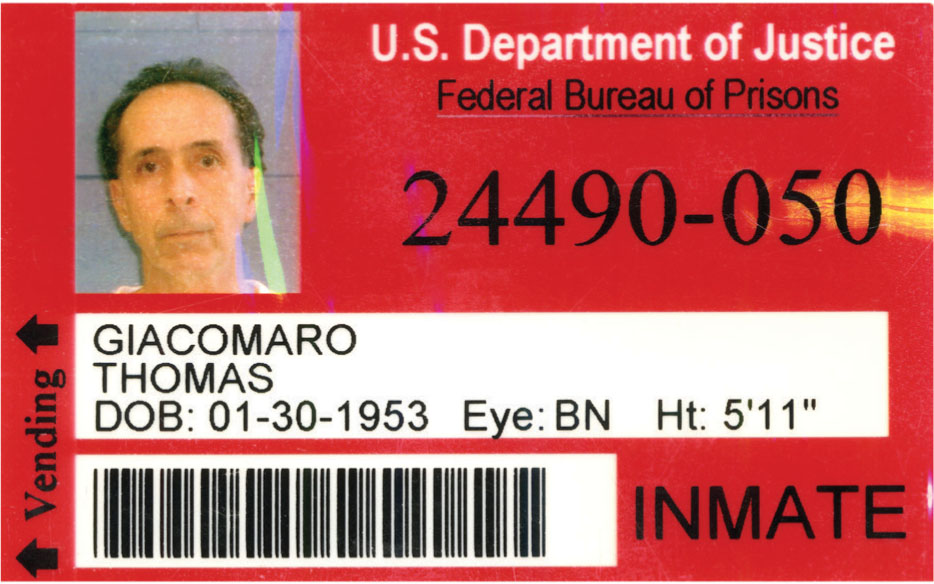

My prison ID . . . I was just a number

For breakfast, lunch, and dinner we had a mob table in the chow hall where a dozen of us sat together, guys from the Bonanno, Genovese, Lucchese, Gambino, and Colombo families—we were just one family in here. We’d meet at the entrance and walk in together like a high school gang and then sit down at our table together. All the other inmates knew not to sit at our table. It was a multigenerational, multifamily sit-down for the country’s top organized criminals—many whose names I can’t mention here, or I’ll have myself a big problem.

We only had fifteen minutes to shove the shitty food in our faces. When we were done, we got up in unison and left together.

Because the food was crap, we often made pasta in our cells. This was an essential, jerry-rigged art form every Italian in prison had to learn if they were going to get their required spaghetti. There were a few ways you could do it. I got a guy working in the plumbing department to smuggle me two electrical cords with the ends cut off. Then I got a guy in the shop department to smuggle me a metal coil. I wrapped the exposed ends of the wires around the ends of the coil and now I’ve got a homemade “stinger.” When you plugged it in and put it in a garbage can filled with water, you got boiling water.

From the commissary, we bought pasta, cheese, and sauce. From the kitchen, we stole garlic and hamburger meat. You put each item in plastic garbage bags and dunk them in the boiling water. I used to line up three garbage cans with three stingers in a row in my cell, like simmering pots on a kitchen stove—one had the pasta, one had the sauce and garlic, one had the meatballs.

Fat Tony, Nicky Glasses, and one or two other key Italians would be invited to my cell for dinner that night and we’d eat on stolen plates and cutlery from the kitchen. It felt good. For a few minutes, we coulda been just a bunch of guys eating linguine on Mulberry Street.

One night over dinner, I told the guys about how I duped Mary Higgins Clark. A few days later, one of the older, wiseguy Genovese guys showed up at my cell with a present from the commissary.

“It’s for you to send to your friend . . . that writer, Mary,” he said. He held up a little card with powder-blue raised lettering on it: “Thinking of You.”

“Why don’t you send it to her! Ha-ha!” laughed one of the other guys. “It can be your way to make it up to her!”

Why not? Inside I scrawled, “Sorry for what I did. I didn’t really mean it,” and put it in the mail. I wasn’t trying to stick it to her, really, I wasn’t.

Three days later the prison alarms went off and the warden locked the entire prison down. I was summoned to go to SIS office (Secret Intelligence Service)—never, ever a good sign. When I arrived, a bunch of FBI guys from Pittsburgh were there with the lieutenant of SIS. Fuck, fuck, fuck.

“How you doin’?” I asked.

“Giacomaro, sit down,” the warden said. “We got an email from the FBI in West Paterson and attached here to the email is a scan of a card: ‘Thinking of You.’ It was sent to Mary Higgins Clark. And we have faxes here from the FBI in Paterson, ‘cease and desist’ letters.”

“Yeah,” I smiled. “I sent her a little note. To be nice.”

“But . . . why the . . .” The warden started to laugh hysterically.

“Mr. Giacomaro,” said one of the FBI agents, “we think it’s really nice and all that you’re thinking of her, but she’s a victim of yours—a VICTIM. Do you understand that? Do you realize who this woman is?”

“Yeah.”

“This is one of the top writers in the country,” says the other agent, sternly. “She’s personal friends with the president!”

“Yeah. Well she’s my friend, too.”

“Giacomaro,” the warden interrupted, still laughing, “just don’t do it again, okay? We have to punish you if you do.”

“I promise. Scout’s honor.”

They made me write it down on a piece of paper, too, like a little kid writing on the chalkboard after he’d done something bad in class.

I promise not to contact Mary ever, ever again.

I promise not to contact Mary ever, ever again.

I promise not to contact Mary ever, ever again.

![]()

The day Fat Tony left Loretto in the summer of 2009, I got his black jogging suit and brand-new Nike sneakers ready for him. I had the jogging suit washed and I ironed it personally and perfectly, and I laced and laid out his sneakers. The night before, I gave him a haircut. When it was time, I walked him to R&D (Receiving and Departure) and sat with him on the bench while they processed his departure paperwork.

“Don’t forget what I told you, Tommy,” he said, as we hugged goodbye. “No regrets. I know you’ll do what’s right.”

Fat Tony was one of the few good friends I’d made in my seven years in prison so far, and when you don’t have family, friends keep you sane and alive. A few months later when they sent me across the street to the Loretto sissy-la-la camp, I met another friend like that.

The Loretto camp was one of the nicest camps in the country. The barracks were immaculate, the grounds were lush, and the food in chow hall was edible. Compared to all the other prisons I’d been to before, this was paradise.

When you sat on the lawn chairs on the grounds, you could see roads of regular traffic just beyond the little “Out of Bounds” signs—freedom was close enough to touch. In fact, you could touch it. Inmates would get their girlfriends or wives to park across the street, and they’d run across for an evening quickie in between counts.

Manuto Nunez had already been at the Loretto sissy-la-la camp for a year before I arrived. He was a tall, young, good-looking jujitsu champ and Cuban drug dealer sentenced to more than a dozen years. Everybody, all the guards and inmates, loved him—he was the opposite of me in personality: nice, sunny, sensitive, like a big, handsome teddy bear. The kinds of qualities you look for in a cocaine dealer. But still.

We met while sitting in a pair of lawn chairs next to each other one afternoon, trying to get a tan. He being Cuban and me being Sicilian, that took about five minutes. But we got to talking and it didn’t take long to discover that it was Manny and his crew who used to supply me with large quantities of coke when I was at the height of my own dealing days. Small world!

We began meeting for regular afternoon talks in the sun, after Manny worked out with the rusty weights in “the shack”—the outdoor gym at the prison. I gave him advice about business and money, and he acted as my loyal bodyguard, getting me out of fights by tackling me to the ground or talking the other, bigger guy down. One day my temper was so crazy and out of control and I needed to fight, so I went after a bunch of big guys with a baseball bat that I got from the shack. Manny jumped me before I hit one of them, a guy who’d been annoying me, and took me down, taking the bat from me.

“You’re gonna kill this guy and they’ll keep you in here forever!” he said.

And yet, he was so loyal that if I told him, “Manny, go kill that piece of shit for me,” he would have.

“When we get out of here,” I promised him, “you’re gonna work for me.”

Manny had connections in the commissary and with the drivers who came into the compound so he arranged to smuggle in some designer jogging suits and half a dozen pairs of Nike sneakers for me. I kept my stash in plastic bins under my lower bunk. Manny did my laundry, and everything was meticulous and perfectly folded—he even wiped my shoes for me every day. He was my protégé.

Walking around the camp together like an oddly match buddy movie—Manny with his easy smile, Latin strut, and biceps like tree trunks, and me with my arrogance and bad-hip limp—we looked like Tony Montana and his sidekick, Manny Ribera, in Scarface. Or Joe Buck and Ratso Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy.

But it was more than that. During our talks, I told him about Lauren and how my family had cut me off. He told me about losing his father, who died a few months before he came to Loretto. Somewhere in the gap of pain and emptiness where I’d lost a child and Manny had lost a parent, we forged a father-son relationship we both needed.

The thing about Manny is he knew how to do jail. He knew how to make friends with the COs and play jail politics while I was confrontational. He waved at the guards when we sunned ourselves and I scowled. He always got extra food in the chow line—two hamburgers, two pieces of chicken—because he knew how to make them like him. It’s what I knew to do and had done on the outside as a salesman, too, but not on the inside.

My first problem was that I could barely admit I was even there. In the nearly eight years I’d been in prison, I still hadn’t given in to the reality that I was a prison inmate with nothing, just like everyone else here—nothing and no one special. I’d survived the worst of it and hadn’t broken so far, and that was good; but I still hadn’t bent. It’s not that I didn’t know how to; it’s that I refused. Judge Wolin nailed it when he sentenced me: I was a “resistant, arrogant felon,” and that was still true. For the first time in my life, I was floundering.

My job at Loretto was to wipe down five fire extinguishers with a wet cloth, that’s it, and I’d be done for the day. It was a total of fifteen minutes of easy work. But I was such a pompous ass that I wouldn’t even do that. When the guards confronted me, I’d say, “I ain’t workin’ today! I’m going to go lie in the sun!”

My first few years incarcerated, I got away with not working much because I was grieving over Lauren’s death. Then, I lucked out with a warden or two who were easy on me. But at Loretto, I was expected to pull my weight and I wasn’t. Manny tried to teach me, to talk to me, because he knew it would lead to trouble.

“Tommy, you gotta give in to these people or they’ll send you away,” he’d say. His job was to mop the kitchen floor for half an hour every day.

“They come to me to ask me why I can’t talk sense into you, Tommy! Why do you keep resisting them? It’s easy. We could have it good here for the next few years!”

“I don’t want to do it,” I’d say. “Fuck them.”

He was right—we were sitting pretty, Manny and I. And I should have been more grateful, seeing that Bernie Madoff was arrested the year before and sentenced to 150 years for his Ponzi scheming. The laws changed for sentencing fraud crimes after I’d gone in and now they were massive. I don’t care how many billions he took; he didn’t take a life, yet they took his.

I was doing great in comparison. But like every other pretty deal I ever had in my life, I had to sabotage it.

A new warden came to the camp in early 2010 and when he heard I refused to work, he pulled the bins out from under my bunk during inspection and tossed my stuff into garbage bags and rusty old lockers. I was outside sunning myself at the time, like a billionaire back in my little fishing village in the South of France. When I returned and saw what he’d done, I blew a fuse. Manny wasn’t there to diffuse it. I raced downstairs where the warden was inspecting the lower barracks.

“Hey, warden, why the fuck did you destroy my clothes?”

“What did you say to me?”

“You heard what the fuck I said.”

Everybody around us was silent, staring at us. The warden didn’t reply, or even hesitate. He turned to the lieutenant next to him: “Handcuff him and put him in the fucking hole. I don’t want to ever see him again.”

Four guys came and dragged me away. Just before I was out of the building, I saw Manny running down the stairs—someone had raced to get him and tell him what was going on. We had only a fraction of a second of eye contact. In that moment, I tried to wordlessly say: We’ll find each other when this is over. But all I could think was I’m sorry, I’m sorry . . .

I was in the hole for one month. Then two months. I went two or three days at a time without food, and then maybe they’d give me half a hot dog or a few beans. Every morning, the warden would come by and bang on the glass window:

“Did they feed you last night, Giacomaro? You’re never going to get out of this hellhole!”

Then three months.

Every night, I sent a letter to the US attorney for help. The COs would hand my letters to the warden, who threw them out. I went from 185 to 150 pounds. He’s trying to kill me. They turned the cold air up and wouldn’t give me a blanket. I got sick and feverish. I laid my head against the cold cement floor and closed my eyes. I was losing my mind.

Dad, you’re going to be okay. You’ll get out.

Lauren honey? How?

One of your letters will get through. The US marshals will come and get you.

But how will I survive the rest of my time in here, baby? I can’t do it.

You’ve got to bend to them, Dad. Talk your way out. Use your smarts and charm. Play their game and beat them at it, like always.

You’ve got to con them in the way that only you can, Daddy . . .