The key tool we use to create and shape our images is light itself, in all its many forms and textures. Indeed, it’s said that Sir John Herschel coined the term “photography” from the Greek words for “writing with light” in a paper read before the Royal Society in March 1839. Our dependence on the qualities of the light we use to produce our images is absolute. An adept photographer knows how to compensate for too much or too little illumination, how to soften harsh lighting to mask defects, or increase its contrast to evoke shape and detail. Sometimes, we must adjust our cameras for the apparent “color” of light, use a brief burst of it to freeze action, or filter it to reduce glare.

This chapter introduces using continuous lighting (such as daylight, incandescent, LED, or fluorescent sources). Then, I’ll cover the brilliant snippets of light we call electronic flash.

Continuous Lighting Basics

While continuous lighting and its effects are generally much easier to visualize and use than electronic flash, there are some factors you need to take into account, particularly the color temperature of the light, how accurately a given form of illumination reproduces colors (we’ve all seen the ghastly looks human faces assume under mercury-vapor lamps outdoors), and other considerations.

Continuous lighting differs from electronic flash, which illuminates our photographs only in brief bursts. Flash, or “strobe” light is notable because it can be much more intense than continuous lighting, lasts only a moment, and can be much more portable than supplementary incandescent sources. It’s a light source you can carry with you and use anywhere. There are advantages and disadvantages to each type of illumination. Here’s a quick checklist of pros and cons:

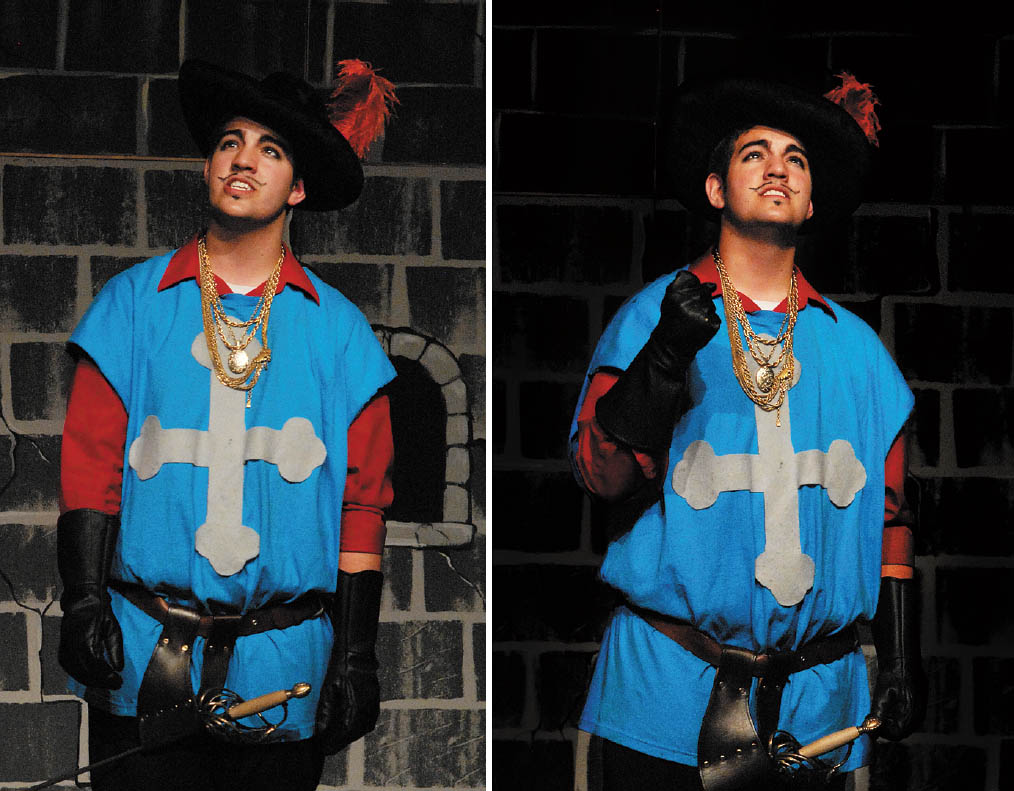

- Lighting preview—Pro: continuous lighting. With continuous lighting, you’ll always know exactly what kind of lighting effect you’re going to get, and, if multiple lights are used, how they will interact with each other. If the natural light present in a scene is perfect for the image you’re trying to capture, you’ll know immediately (see Figure 11.1, left).

- Lighting preview—Con: electronic flash. With flash, unless you have a modeling light built into the flash, the general effect you’re going to see may be a mystery until you’ve built some experience, and you may need to review a shot, make some adjustments, and then reshoot to get the look you want. An image like the candle-lit scene in the figure would have been difficult to achieve even with an off-camera battery-powered flash unit, because it would be tricky to balance the illumination of the candles with the light from the flash. While the modeling light feature offered by some Canon flash units can be helpful, it’s not a true continuous modeling light.

Figure 11.1 You always know how the lighting will look when using continuous illumination (left). Electronic flash can freeze almost any action (right).

- Exposure calculation—Pro: continuous lighting. Your 90D has no problem calculating exposure for continuous lighting, because it remains constant and can be measured directly from the light reaching the sensor. The 90D’s Spot metering mode can be used to measure and compare the proportions of light in the highlights and shadows, so you can make an adjustment (such as using more or less fill light) if necessary. If you want the utmost precision, you can even use a hand-held light meter to measure the light yourself, and then set the shutter speed and aperture to match in Manual exposure mode.

- Exposure calculation—Con: electronic flash. Electronic flash illumination doesn’t exist until the flash fires, and so can’t be measured by the 90D’s exposure sensor at the moment of exposure. Instead, the light must be measured by metering the intensity of a pre-flash triggered an instant before the main flash, as it is reflected back to the camera and through the lens.

- Evenness of illumination—Pro/con: continuous lighting. Of the continuous light sources, daylight, in particular, provides illumination that tends to fill an image completely, lighting up the foreground, background, and your subject almost equally. Shadows do come into play, of course, so you might need to use reflectors or fill in additional light sources to even out the illumination further. Indoors, however, continuous lighting is commonly less evenly distributed. The average living room, for example, has hot spots near the lamps and overhead lights, and dark corners located farther from those light sources. But on the plus side, you can easily see this uneven illumination and compensate with additional lamps.

- Evenness of illumination—Con: electronic flash. Electronic flash units, like continuous light sources such as lamps that don’t have the advantage of being located 93 million miles from the subject, suffer from the effects of their proximity. The inverse square law, first applied to both gravity and light by Sir Isaac Newton, dictates that as a light source’s distance increases from the subject, the amount of light reaching the subject falls off proportionately to the square of the distance. In plain English, that means that a flash or lamp that’s twelve feet away from a subject provides only one-quarter as much illumination as a source that’s six feet away (rather than half as much). This translates into relatively shallow “depth-of-light.” I’ll discuss this aspect again later in this chapter.

- Action stopping—Pro: electronic flash. When it comes to the ability to freeze moving objects in their tracks, the advantage goes to electronic flash. The brief duration of electronic flash serves as a very high “shutter speed” when the flash is the main or only source of illumination for the photo. Your 90D’s shutter speed may be set for 1/250th second during a flash exposure, but if the flash illumination predominates, the effective exposure time will be the 1/1000th to 1/50000th second or less duration of the flash, as you can see in Figure 11.1, right, because the flash unit reduces the amount of light released by cutting short the duration of the flash. The only fly in the ointment is that, if the ambient light is strong enough, it may produce a secondary, “ghost” exposure, as I’ll explain later in this chapter.

- Action stopping—Con: continuous lighting. Action stopping with continuous light sources is completely dependent on the shutter speed you’ve dialed in on the camera. And the speeds available are dependent on the amount of light available and your ISO sensitivity setting.

- Cost—Pro: continuous lighting. Incandescent, fluorescent, or LED lamps are generally much less expensive than electronic flash units, which can easily cost several hundred dollars.

- Cost—Con: electronic flash. Electronic flash units aren’t particularly cheap. The lowest-cost dedicated flash designed specifically for the Canon EOS cameras is about $150 (the EL-100), and it is probably not powerful enough for an advanced camera like the 90D. Plan on spending more money to get the features that a sophisticated electronic flash offers.

- Flexibility—Pro: electronic flash. Electronic flash’s action-freezing power allows you to work without a tripod in the studio (and elsewhere), adding flexibility and speed when choosing angles and positions. Flash units can be easily filtered, and, because the filtration is placed over the light source rather than the lens, you don’t need to use high-quality filter material.

- Flexibility—Con: continuous lighting. Because incandescent and fluorescent lamps are not as bright as electronic flash, the slower shutter speeds required mean that you may have to use a tripod more often, especially when shooting portraits. The incandescent variety of continuous lighting gets hot, especially in the studio. The heat also makes it more difficult to add filtration to incandescent sources. (It’s no wonder that LED illumination is rapidly becoming the go-to continuous light source for photography.)

Living with Color Temperature

In practical terms, color temperature is how “bluish” or how “reddish” the light appears to be to the digital camera’s sensor. Indoor illumination is quite warm, comparatively, and appears reddish to the sensor. Daylight, in contrast, seems much bluer to the sensor. Our eyes (our brains, actually) are quite adaptable to these variations, so white objects don’t appear to have an orange tinge when viewed indoors, nor do they seem excessively blue outdoors in full daylight. Yet, these color temperature variations are real, and the sensor is not fooled. To capture the most accurate colors, we need to take the color temperature into account in setting the color balance (or white balance) of the 90D—either automatically using the camera’s intelligence or manually using our own knowledge and experience.

While Canon has been valiant in its efforts to smarten up the 90D’s ability to adjust for color balance automatically, an entire cottage industry has developed to provide us additional help, including gadgets like the ExpoDisc filter/caps and their ilk (www.expoimaging.com), which allow the camera’s add-on external custom white balance measuring feature to evaluate the illumination that passes through the disc/cap/filter/Pringle’s can lid, or whatever neutral-color substitute you employ. (A white or gray card also works.) Unfortunately, to help us tangle with the many different types of non-incandescent/non-daylight sources, Canon has provided the 90D with only a single White Fluorescent setting (some competing models offer more than a half-dozen different presets for fluorescents, sodium-vapor, and mercury vapor illumination). When it comes to zeroing in on the exact color temperature for a scene, your main tools will be custom white balances set using neutral targets like the ExpoDisc, and adjustment of RAW files when you import photos into your image editor.

The only time you need to think in terms of actual color temperature is when you’re adjusting using the Color Temp. setting in the White Balance entry of the Shooting 3 menu, as described in Chapter 7. It allows you to dial in exact color temperatures, if known. You can also shift and bias color balance along the blue/amber and magenta/green axes, and bracket white balance.

In most cases, however, the Auto setting in the Shooting menu’s White Balance entry will do a good job of calculating white balance for you. Auto can be used as your choice most of the time. Use the preset values or set a custom white balance that matches the current shooting conditions when you need to.

Remember that if you shoot RAW, you can specify the white balance of your image when you import it into Photoshop, Photoshop Elements, or another image editor using Adobe Camera Raw, or your preferred RAW converter. While color-balancing filters that fit on the front of the lens exist, they are primarily useful for film cameras, because film’s color balance can’t be tweaked as extensively as that of a sensor.

White Balance Bracketing

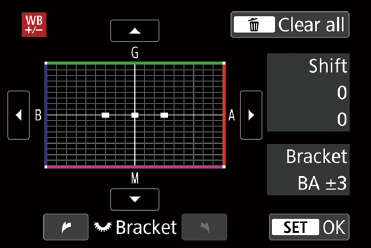

When using WB bracketing, the 90D takes a single shot, and then saves multiple JPEG copies, each with a different color balance. It’s not necessary to capture multiple shots, as the camera uses the raw information retrieved from the sensor for the single exposure and then processes it to generate the multiple different versions. When you select White Balance Shift/Bracketing from the Shooting 3 menu, the bracketing adjustments are made on the blue/amber axis when you rotate the Quick Control Dial in the clockwise direction; to bracket along the magenta/green axis, rotate the QCD in the counter-clockwise direction. (See Figure 11.2.)

Figure 11.2 White balance bracketing can be done along the blue/amber or magenta/green axes.

Electronic Flash Basics

Until you delve into the situation deeply enough, it might appear that serious photographers have a love/hate relationship with electronic flash. You’ll often hear that flash photography is less natural looking, and that the built-in flash in most cameras should never be used as the primary source of illumination because it provides a harsh, garish look. Available (“continuous”) lighting is praised, and flash, especially using the built-in flash, seems to be roundly denounced.

In truth, however, the bias is against bad flash photography, the kind produced when you elevate the built-in flash, or clamp an external flash on top of the camera and point it directly at your subject. In that mode, you’ll often end up with well-exposed (thanks to Canon’s e-TTL II metering system), but harshly lit images. Yet, in other configurations, flash has become the studio light source of choice for pro photographers, because it’s more intense (and its intensity can be varied to order by the photographer), freezes action, frees you from using a tripod (unless you want to use one to lock down a composition), and has a snappy, consistent light quality that matches daylight. (While color balance changes as the flash duration shortens, some Canon flash units can communicate to the camera the exact white balance provided for that shot.) And even pros will cede that an external flash has some important uses as an adjunct to existing light, particularly to illuminate dark shadows using a technique called fill flash. Moreover, creative photographers can use their 90D’s built-in flash or an external Speedlite in remarkably creative ways, especially in wireless and multiple flash modes (which I’ll explain in Chapter 12).

How Electronic Flash Works

The bursts of light we call electronic flash are produced by a flash of photons generated by an electrical charge that is accumulated in a component called a capacitor and then directed through a glass tube containing xenon gas, which absorbs the energy and emits the brief flash. For a typical external flash attached to the 90D, such as the top-of-the-line Speedlite 600EX II-RT, the full burst of light lasts about 1/1000th of a second and provides enough illumination to shoot a subject 12 feet away at f/16 using the ISO 100 setting.

Because the duration of the burst is so brief, if the external flash is the main source of illumination, the effective exposure time is short, typically 1/1000th to 1/50000th second, freezing a moving subject dramatically. These short bursts can also be repeated, producing multiple-exposure/stroboscopic effects, as described later in this chapter.

An electronic flash is triggered at the instant of exposure, during a period when the sensor is fully exposed by the shutter. The 90D has a vertically traveling shutter that consists of two curtains. The first curtain opens and moves to the opposite side of the frame, at which point the shutter is completely open. The flash can be triggered at this point (so-called first-curtain sync), making the flash exposure. Then, after a delay that can vary from 30 seconds to 1/250th second (with the 90D; other cameras may sync at a faster or slower speed), a second curtain begins moving across the sensor plane, covering up the sensor again. If the flash is triggered just before the second curtain starts to close, then second-curtain sync is used. In both cases, though, a shutter speed of 1/250th second is the maximum that can be used to take a photo (unless you’re using high-speed sync, discussed later in this chapter).

Figure 11.3 illustrates how this works. At upper left, you can see a fanciful illustration of a generic shutter with both curtains tightly closed. (Your shutter does not actually look like this, as you can confirm by removing your lens when the camera is powered off and the shutter closes to protect the sensor.) At upper right, the first curtain begins to move downward, starting to expose a narrow slit that reveals the sensor behind the shutter. At lower left, the first curtain moves downward farther until, as you can see at lower right in the figure, the sensor is fully exposed.

Figure 11.3 A focal plane shutter has two curtains, the upper, or first curtain, and a lower, second curtain.

When 1st Curtain is used, the flash is triggered at the instant that the sensor is completely exposed. The shutter then remains open for an additional length of time (from 30 seconds to 1/250th second), and the second curtain begins to move downward, covering the sensor once more. When 2nd Curtain is activated, the flash is triggered after the main exposure is over, just before the second curtain begins to move downward.

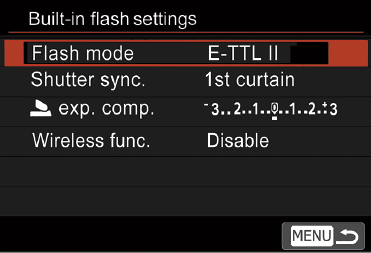

Ghost Images

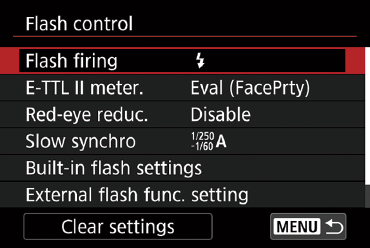

The difference between triggering the flash when the shutter just opens, or just when it begins to close might not seem like much. But whether you use 1st Curtain (the default setting) or 2nd Curtain (an optional setting) can make a significant difference to your photograph if the ambient light in your scene also contributes to the image. You can set either of these sync modes in the Flash Control entry of the Shooting 1 menu. The adjustment is available for both the 90D’s pop-up flash (tucked away as the Shutter Sync. option in the Built-in Flash Settings entry) and for external flash mounted on the camera and powered up (under External Flash Function setting). (See Figure 11.4.)

Figure 11.4 Choose 1st Curtain or 2nd Curtain from the External Flash Function setting in the Flash Control menu.

At faster shutter speeds, particularly 1/250th second, there isn’t much time for the ambient light to register, unless it is very bright. It’s likely that the electronic flash will provide almost all the illumination, so 1st Curtain or 2nd Curtain isn’t very important. However, at slower shutter speeds, or with very bright ambient light levels, there is a significant difference, particularly if your subject is moving, or the camera isn’t steady.

In any of those situations, the ambient light will register as a second image accompanying the flash exposure, and if there is movement (camera or subject), that additional image will not be in the same place as the flash exposure. It will show as a ghost image and, if the movement is significant enough, as a blurred ghost image trailing in front of or behind your subject in the direction of the movement.

As I noted, when you’re using 1st Curtain, the flash’s main burst goes off the instant the shutter opens fully (a pre-flash used to measure exposure in auto flash modes fires before the shutter opens). This produces an image of the subject on the sensor. Then, the shutter remains open for an additional period (30 seconds to 1/250th second, as I said). If your subject is moving, say, toward the right side of the frame, the ghost image produced by the ambient light will produce a blur on the right side of the original subject image, making it look as if your sharp (flash-produced) image is chasing the ghost. For those of us who grew up with lightning-fast superheroes who always left a ghost trail behind them, that looks unnatural (see Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5 1st Curtain produces an image that trails in front of the flash exposure (top), whereas 2nd Curtain creates a more “natural-looking” trail behind the flash image.

So, Canon uses 2nd Curtain to remedy the situation. In that mode, the shutter opens, as before. The shutter remains open for its designated duration, and the ghost image forms. If your subject moves from the left side of the frame to the right side, the ghost will move from left to right, too. Then, about 1.5 milliseconds before the second shutter curtain closes, the flash is triggered, producing a nice, sharp flash image ahead of the ghost image. Voilà! We have monsieur Speed Racer outdriving his own trailing image.

Avoiding Sync-Speed Problems

Using a shutter speed faster than 1/250th second can cause problems. Triggering the electronic flash only when the shutter is completely open makes a lot of sense if you think about what’s going on. To obtain shutter speeds faster than 1/250th second, the 90D exposes only part of the sensor at one time, by starting the second curtain on its journey before the first curtain has completely opened, as shown in Figure 11.6. That effectively provides a briefer exposure as a slit, narrower than the full height of the sensor, passes above its surface. If the flash were to fire during the time when the first and second curtains partially obscured the sensor, only the slit that was open would be exposed.

You’d end up with only a narrow band, representing the portion of the sensor that was exposed when the picture is taken. For shutter speeds faster than 1/250th second, the second curtain begins moving before the first curtain reaches the bottom of the frame. As a result, a moving slit, the distance between the first and second curtains, exposes one portion of the sensor at a time as it moves from the top to the bottom. Figure 11.6 shows three views of our typical (but imaginary) focal plane shutter. At left is pictured the closed shutter; in the middle version you can see the first curtain has moved down about 1/4 of the distance from the top; and in the right-hand version, the second curtain has started to “chase” the first curtain across the frame toward the bottom.

Figure 11.6 A closed shutter (left); partially open shutter as the first curtain begins to move downward (middle); only part of the sensor is exposed as the slit moves (right).

If the flash is triggered while this slit is moving, only the exposed portion of the sensor will receive any illumination. You end up with a photo like the one shown in Figure 11.7. Note that the band across the bottom of the image is black. That’s a shadow of the second shutter curtain, which had started to move when the flash was triggered. Sharp-eyed readers will wonder why the black band is at the bottom of the frame rather than at the top, where the second curtain begins its journey. The answer is simple: your lens flips the image upside down and forms it on the sensor in a reversed position. You never notice that, because the camera is smart enough to show you the pixels that make up your photo in their proper orientation. But this image flip is why, if your sensor gets dirty and you detect a spot of dust in the upper half of a test photo, if cleaning manually, you need to look for the speck in the bottom half of the sensor.

Figure 11.7 If a shutter speed faster than 1/250th second is used, you can end up photographing only a portion of the image.

I generally end up with sync-speed problems only when shooting in the studio, using studio flash units rather than my 90D’s Canon-dedicated Speedlite. That’s because if you’re using a “smart” (dedicated) flash, the camera knows that a strobe is attached, and remedies any unintentional goof in shutter speed settings. If you happen to set the 90D’s shutter to a faster speed in Tv or M mode, the camera will automatically adjust the shutter speed down to 1/250th second. In Av, P, or Scene Intelligent Auto modes where the 90D selects the shutter speed, it will never choose a shutter speed higher than 1/250th second when using flash. In P mode, shutter speed is automatically set between 1/60th to 1/250th second when using flash.

But when using a non-dedicated flash, such as a studio unit plugged into a PC/X adapter (an accessory that fits into the flash shoe and provides a “dumb” flash connector), the camera has no way of knowing that a flash is connected, so shutter speeds faster than 1/250th second can be set inadvertently. Note that the 90D can use a feature called high-speed sync that allows shutter speeds faster than 1/250th second with certain external dedicated Canon flash units. When using high-speed sync (HSS), the flash fires a continuous serious of bursts at reduced power for the entire exposure, so that the duration of the illumination is sufficient to expose the sensor as the slit moves. High-speed sync is set using the controls on the attached and powered-up compatible external flash. I’ll explain HSS later.

Determining Exposure

Calculating the proper exposure for an electronic flash photograph is a bit more complicated than determining the settings by continuous light. The right exposure isn’t simply a function of how far away your subject is (which the 90D can figure out based on the autofocus distance that’s locked in just prior to taking the picture). Various objects reflect more or less light at the same distance so, obviously, the camera needs to measure the amount of light reflected back and through the lens. Yet, as the flash itself isn’t available for measuring until it’s triggered, the 90D has nothing to measure.

The solution is to fire the flash multiple times. The initial shot is a pre-flash that can be analyzed, then followed by a main flash that’s given exactly the calculated intensity needed to provide a correct exposure. If the main flash is serving as a master to trigger off-camera flash units, additional coded pulses can convey settings information to the slave flashes and trigger their firing. Of course, if radio signals rather than optical signals are in play, the sequences may be different. I’ll cover various radio and optical wireless flash modes in Chapter 12; this chapter just explains the basics.

Because of the need to abbreviate or quench a flash burst in order to provide the optimum exposure, the primary flash may be longer for distant objects and shorter for closer subjects, depending on the required intensity. This through-the-lens evaluative flash exposure system is called E-TTL II, and it operates whenever you have attached a Canon-dedicated flash unit to the 90D.

Guide Numbers

Guide numbers, usually abbreviated GN, are a way of specifying the power of an electronic flash in a way that can be used to determine the right f/stop to use at a particular shooting distance and ISO setting. In fact, before automatic flash units became prevalent, the GN was used to do just that. A GN is usually given as a pair of numbers for both feet and meters that represent the range at ISO 100. For example, consider the Canon Speedlite 270EX II, the least powerful of Canon’s current external flash units (aside from the mini 90EX, primarily intended for use on Canon’s non-dSLR models). The 270EX II has a GN of 89 at ISO 100. That Guide Number applies when the flash is set to the 50mm zoom setting (so that the unit’s coverage is optimized to fill up the frame when using a 50mm focal length on a full-frame camera body). (The effective Guide Number is just 72 when the flash is mounted on a “cropped” sensor camera like the EOS 90D.) If you’re using the 270EX II set to the 28mm zoom position, the light spreads out more to cover the wider area captured at that focal length, and the Guide Number of the unit drops to 79.

Of course, the question remains, what can you do with a Guide Number, other than to evaluate relative light output when comparing different flash units? In theory, you could use the GN to calculate the approximate exposure that would be needed to take a photo at a given distance. To calculate the right exposure at ISO 100, you’d divide the guide number by the distance to arrive at the appropriate f/stop. (Remember that the shutter speed has no bearing on the flash exposure; the flash burst will occur while the shutter is wide open and will have a duration of less than the time the shutter is open.)

Again, using the 270EX II as an example, at ISO 100 with its GN of 89, if you wanted to shoot a subject at 11 feet, you’d use f/8 (89 divided by 11). At approximately 16 feet, an f/stop of f/5.6 would be used. Some quick mental calculations with the GN will give you any electronic flash’s range. You can easily see that the 270EX II would begin to peter out at about 32 feet, where you’d need an aperture of roughly f/2.8 at ISO 100. Of course, in the real world you’d probably bump the sensitivity up to a setting of ISO 400 so you could use a more practical f/5.6 at that distance.

You should use Guide Numbers as an estimate only. Other factors can affect the relative “power” of a flash unit. For example, if you’re shooting in a small room. Some light will bounce off ceilings and walls—even with the flash pointed straight ahead—and give your flash a slight boost, especially if you’re not shooting extra close to your subject. Use the same flash outdoors at night, say, on a football field, and the flash will have less relative power, because helpful reflections from surrounding objects are not likely.

So, today, guide numbers are most useful for comparing the power of various flash units. You don’t need to be a math genius to see that an electronic flash with a GN of, say, 197 (like the 600EX II-RT) would be a lot more powerful than that of the 270EX II. You could use f/12 instead of f/5.6 at 16 feet. That’s slightly more than two full f/stops’ difference. As a Canon 90D owner, we can safely assume you’ll be using one of the more powerful flash units in the Canon line (or perhaps a similar unit from a third-party vendor).

Getting Started with Electronic Flash

The Canon 90D’s built-in flash is a handy accessory because it is available as required, without the need to carry an external flash around with you constantly. External flash offer more flexibility and additional power. The next sections explain how to use both.

Flash in Other Modes

When you’re using Scene modes, Scene Intelligent Auto, P, Av, Tv, B, or Manual exposure modes, pop up the built-in flash by pressing the button on the left side of the pentaprism housing, or attach an external flash and turn it on. The behavior of the flash varies, depending on which exposure mode you’re using:

- Scene Intelligent Auto/Scene modes. When the 90D is set to these modes, the flash will fire automatically, if it is attached and powered up.

- P. In Program mode, the 90D fully automates the exposure process, giving you subtle fill-flash effects in daylight, and fully illuminating your subject under dimmer lighting conditions. The camera selects a shutter speed from 1/60th to 1/250th second and sets an appropriate aperture.

- Av. In Aperture-priority mode, you set the aperture as always, and the 90D chooses a shutter speed from 30 seconds to 1/250th second. Use this mode with care, because if the camera detects a dark background, it will use the flash to expose the main subject in the foreground, and then leave the shutter open long enough to allow the background to be exposed correctly, too. If you’re not using an image-stabilized lens, you can end up with blurry ghost images even of non-moving subjects at exposures longer than 1/30th second, and if your camera is not mounted on a tripod, you’ll see these blurs at exposures longer than about 1/8th second even if you are using IS.

To disable use of a slow shutter speed with flash, access the Slow Synchro option in the External Speedlite Control entry in the Shooting 2 menu, and change from the default setting (Auto) to either 1/250-1/60sec. auto or 1/250sec. (fixed).

- Tv. When using flash in Tv mode, you set the shutter speed from 30 seconds to 1/250th second, and the 90D will choose the correct aperture for the correct flash exposure. If you accidentally set the shutter speed higher than 1/250th second, the camera will reduce it to 1/250th second when you’re using the flash.

- Av. In this mode, you can specify shutter speed, aperture, and ISO sensitivity either manually or automatically, and the 90D will adjust the remaining parameters. That means when using flash, the camera will behave as if it were in Program mode (if you don’t choose a shutter speed or aperture manually), Tv mode (if you select only a shutter speed), Av mode (if you choose only the aperture), or M mode (if you select both).

- M/B. In Manual or Bulb exposure modes, you select both shutter speed (30 seconds to 1/250th second) and aperture. The camera will adjust the shutter speed to 1/250th second if you try to use a faster speed with a flash. The E-TTL II system will provide the correct amount of exposure for your main subject at the aperture you’ve chosen (if the subject is within the flash’s range, of course). In Bulb mode, the shutter will remain open for as long as the release button on top of the camera is held down, or the release of your remote control is activated. If you use the Bulb timer, you can specify long exposures.

Flash Range

The illumination of the 90D’s flash varies with distance, focal length, and ISO sensitivity setting.

- Distance. The farther away your subject is from the camera, the greater the light fall-off, thanks to the inverse square law. Keep in mind that a subject that’s twice as far away receives only one-quarter as much light, which is two f/stops’ worth. (See Figure 11.8.)

- Focal length. The built-in flash “covers” only a limited angle of view, which doesn’t change. So, when you’re using a lens that is wider than the default focal length, the frame may not be covered fully, and you’ll experience dark areas, especially in the corners. As you zoom in using longer focal lengths, some of the illumination is outside the area of view and is “wasted.” (This phenomenon is why some external flash units, such as the 600EX RT-II, “zoom” to match the zoom setting of your lens to concentrate the available flash burst onto the actual subject area.)

- ISO setting. The higher the ISO sensitivity, the more photons captured by the sensor. So, doubling the sensitivity from ISO 100 to 200 produces the same effect as, say, opening up your lens from f/8 to f/5.6.

Figure 11.8 A subject that is twice as far away receives only one-quarter as much illumination.

Red-Eye Reduction and Autofocus Assist

When Red-Eye Reduction is turned on in the Flash Control entry of the Shooting 1 menu (as described in Chapter 7), and you are using flash with any shooting mode except for Landscape, Sports, Panning, Food, HDR Backlight Control, or Movie), the red-eye reduction lamp on the front of the camera will illuminate for about 1.5 seconds when you press down the shutter release halfway, theoretically causing your subjects’ irises to contract (if they are looking toward the camera), and thereby reducing the red-eye effect in your photograph. Red-eye effects are most frequent under low-light conditions, when the pupils of your subjects’ eyes open to admit more light, thus providing a larger “target” for your flash’s illumination to bounce back from the retinas to the sensor.

Another phenomenon you’ll encounter under low-light levels may be difficulty in focusing. Canon’s answer to that problem is an autofocus assist beam emitted by the 90D’s built-in flash, if elevated, or by any external dedicated flash unit that you may have attached to the camera (and switched on). In dim lighting conditions, the built-in flash will emit a burst of reduced-intensity flashes when you press the shutter release halfway, providing additional illumination for the autofocus system. The AF-assist beam is emitted only during viewfinder shooting, or when using AI Focus or AI Servo AF.

The AF-assist beam settings entry of the Shooting 6 menu has four options:

- On (Enable). The AF-assist beam will fire when required. If an external flash’s AF-assist beam Custom Function is set to Disable, the beam will not fire. If you’re using the built-in flash instead of an external flash, elevate the flash by pressing the Flash button.

- Off (Disable). Turns off the AF-assist beam.

- Enable External Flash Only. The beam will fire only when an external flash is mounted and powered up. If the external flash’s AF-assist beam Custom Function is set to Disable, the beam will not fire. When shooting in live view mode with a Speedlite offering a built-in LED movie lamp, the lamp will be used for the AF-assist function.

- IR AF-assist beam only. Enables a less obtrusive (non-visible) infrared AF-assist beam available from external Speedlites that include that feature, such as the Speedlite 600EX II-RT.

Flash Exposure Compensation and FE Lock

If you want to lock flash exposure for a subject that is not centered in the frame, you can use the FE lock (the * button) to lock in a specific flash exposure. Just center the viewfinder on the subject you want to correctly expose and press the * button. The pre-flash fires and calculates exposure. The 90D remembers the correct exposure until you take a picture, and the FEL indicator, a lightning bolt with an * next to it in the lower-left corner of the display, is your reminder. If you want to recalculate your flash exposure, just press the * button again. When you’re ready to shoot, recompose your photo and press the shutter down the rest of the way to take the picture.

You can also manually add or subtract exposure to the flash exposure. When using Program AE, Aperture-priority, Shutter-priority, or Manual exposure modes, you can access flash exposure compensation (FEC) in four different ways.

- Set FEC on the external flash. Consult your Speedlite manual to see if you can set flash exposure compensation on the flash. See the sidebar which follows. Note that when you specify FEC on the flash, you cannot change it using the camera’s controls.

- Quick Control screen “fast” setting. Press the Q button to access the Quick Control screen. Highlight the FEC icon, located second from the right in the second row (see Figure 11.9, top) when Flash Exposure compensation is highlighted. Then rotate the Main Dial to add or subtract flash exposure. Use this method when you’re in a hurry.

- Quick Control screen “scale” setting. Press the Q button to access the Quick Control screen. Highlight the FEC icon, and press SET or the multi-controller. A screen like the one seen at the bottom of Figure 11.9 appears. You might want to do this if you preferred to use the touch screen to make your adjustments or needed the extra legibility the larger screen provides.

Figure 11.9 The built-in flash’s Flash Exposure Compensation can be set from the Quick Control Screen (top); a scale is also available (bottom).

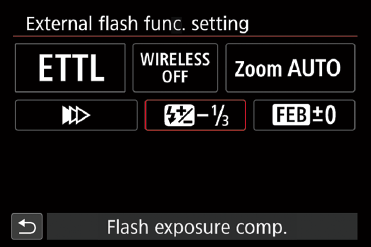

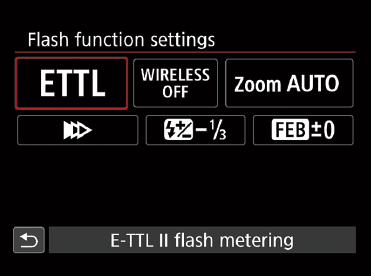

- Access Flash Control. Find it in the Shooting 1 menu and press SET. You can then select Built-in Flash Settings (to access a scale that lets you adjust plus or minus three stops) or External Flash Function Settings. If you have an external flash attached and powered up, the External Flash Function Settings entry produces a screen like the one shown in Figure 11.10. Then navigate to the Flash Exposure Compensation icon in the second row of the screen and press SET to access this sliding scale. You might go this route if you were making multiple settings, including FEC, from that screen.

Figure 11.10 Flash exposure compensation can be set from the Shooting 1 menu’s External Speedlite Control options.

SETTING FEC ON THE FLASH

While setting flash exposure compensation within the camera is usually most convenient, with some Canon Speedlites (such as the 600EX II-RT), you can set exposure compensation on the external flash instead. With the 600EX II-RT, in ETTL, M, or MULTI modes, press the #2 button to highlight the +/- FEC indicator, then rotate the flash’s Select dial to set the specific amount. Press the Select/SET button to confirm your choice.

If you want to avoid accidentally changing the FEC value on the flash, say, while making other adjustments, use either flash unit’s C.Fn-13 setting (not to be confused with the 90D’s own Custom Functions). When set to the default, 0, rotating the Select dial specifies the amount; change to 1, instead, and you must first press the Select/SET button before rotating the dial.

Flash exposure compensation can work in tandem with non-flash exposure compensation, so you can adjust the amount of light registered from the scene by ambient light even while you’re tweaking the amount of illumination absorbed from your flash unit. As with non-flash exposure compensation, the compensation you make remains in effect for the pictures that follow, and even when you’ve turned the camera off, remember to cancel the flash exposure compensation adjustment by reversing the steps used to set it when you’re done using it.

TIPIf you’ve enabled the Auto Lighting Optimizer in the Shooting 3 menu, it may cancel out any EV you’ve subtracted using flash exposure compensation. Disable the Auto Lighting Optimizer if you find your images are still too bright when using flash exposure compensation.

More on Flash Control Settings

I introduced the Shooting 1 menu’s Flash Control settings in Chapter 7. This next section offers additional information for using the Flash Control menu. The menu includes seven options (with six of them shown earlier in Figure 11.4): Flash Firing, E-TTL II Metering, Red-eye Reduction, Slow Synchro, Built-in Flash Settings, External Flash Function Settings, and External Flash C.Fn Settings. There is also a Clear Settings option to return the settings to their default values.

Flash Firing

This menu entry has two options: Fire and Off. It can be used to activate or deactivate the built-in electronic flash and any attached external electronic flash unit. When disabled, the flash cannot fire even if you accidentally elevate it, or have an accessory flash attached and turned on. However, you should keep in mind that the AF-assist beam can still be used. If you want to disable that, too, you’ll need to turn it off using the entry in the Shooting 6 menu.

Here are some applications where I always disable my flash and AF-assist beam, even though my 90D won’t pop up the flash and fire without my intervention anyway. Some situations are too important to take chances. (Who knows, maybe I’ve accidentally set the Mode Dial to SCN?)

- Venues where flash is forbidden. I’ve discovered that many No Photography signs actually mean “No Flash Photography,” either because those who make the decisions feel that flash is distracting or they fear it may potentially damage works of art. Tourists may not understand the difference between flash and available-light photography, or may be unable to set their camera to turn off the flash. One of the first phrases I learn in any foreign language is “Is it permitted to take photos if I do not use flash?” A polite request, while brandishing an advanced camera like the 90D (which may indicate you know what you are doing), can often result in permission to shoot away.

- Venues where flash is ineffective anyway. We’ve all seen the concert goers who stand up in the last row to shoot flash pictures from 100 yards away. I tend to not tell friends that their pictures are not going to come out, because they usually show me a dismal, grainy shot (actually exposed by the dim available light) that they find satisfactory, just to prove I was wrong.

- Venues where flash is annoying. If I’m taking pictures in a situation where flash is permitted, but mostly supplies little more than visual pollution, I’ll disable or avoid using it. Concerts or religious ceremonies may allow flash photography, but who needs to add to the blinding bursts when you have a camera that will take perfectly good pictures at ISO 3200? Of course, I invariably see one or two people flashing away at events where flash is not allowed, but that doesn’t mean I am eager to join in the festivities.

E-TTL II Metering

The second choice in the Flash Control menu allows you to choose the type of exposure metering the 90D uses for electronic flash. You can select the default Evaluative (Face Priority) metering, which selectively interprets the metering zones in the viewfinder to intelligently classify the scene for exposure purposes, using face detection to locate and accommodate your human subjects. That setting’s near-twin is the Evaluative option, which performs the same function without searching for faces. Alternatively, you can select Average, which melds the information from all the zones together as an average exposure. You might find this mode useful for evenly lit scenes, but, in most cases, exposure won’t be exactly right, and you may need some flash exposure compensation adjustment.

Red-eye Reduction

Here you can enable or disable use of the 90D’s red-eye reduction feature, described earlier in this chapter.

Slow Synchro

You can select the flash synchronization speed that will be used when working in Aperture-priority mode; choose from Auto (the 90D selects the shutter speed from 30 seconds to 1/250th second) to a range embracing only the speeds from 1/250th to 1/60th second, or fixed at 1/250th second.

Normally, in Aperture-priority mode when using flash, you specify the f/stop to be locked in. The exposure is then adjusted by varying the output of the electronic flash. Because the primary exposure comes from the flash, the main effects of the shutter speed selected is on the secondary exposure from the ambient light on the scene. Your choices include:

- Auto. This is your best choice under most conditions. The 90D will analyze your scene and choose a shutter speed that balances flash exposure and available light. For example, if the camera determines that a flash exposure requires an aperture of f/5.6, and then determines that the background illumination is intense enough to produce an exposure of 1/30th second at f/5.6, it might choose that slow shutter speed to provide a balanced exposure. As you might guess, the chief problem with Auto is that the 90D can choose a shutter speed that is slow enough to cause ghost images, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Don’t use Auto if the ambient light is bright and your subject is far from the camera—that combination can lead to large f/stops and slow shutter speeds. (Use a tripod in such situations.) On the other hand, if your subject is fairly close to the camera—10 feet or closer—Auto will rarely get you into trouble. (See Figure 11.11.)

Figure 11.11 At left, a shutter speed of 1/60th second was used, allowing ambient illumination to brighten the background. At right, a 1/250th second shutter speed produced a black background.

- 1/250–1/60 sec. auto. If you want to ensure that a slow shutter speed won’t be used, activate this option to lock out shutter speeds slower than 1/60th second.

- 1/250 sec. (fixed). This setting ensures that the 90D will always select 1/250th second. You’ll end up with pitch-black backgrounds much of the time, but you won’t have to worry about ghost images.

Built-in Flash Settings

There are four main settings for this menu choice, which normally appears as shown in Figure 11.12. You cannot select Built-in Flash Settings if an external flash is attached to the accessory shoe. A message will pop up explaining that this menu option has been disabled.

However, that does not mean that you can’t use an external Speedlite at the same time as the built-in flash; your add-on flash unit must be used off-camera and not attached to the 90D’s accessory shoe. Indeed, this menu entry has additional settings that apply when using an off-camera wireless external flash, such as Channel and Firing Group, which I’ll address in the sections on external flash.

Figure 11.12 Four entries are available from the Built-in Flash Functions menu.

Here’s a quick summary of the main built-in flash selections, plus additional options that appear when you change the Built-in Flash setting to one of the two wireless flash modes. I’ll explain each in more detail in the sections that follow this one, and in Chapter 12.

- Flash mode. This entry allows you to choose automatic exposure calculation with E-TTL II, or Manual flash.

- Shutter sync. Available only in E-TTL mode, you can choose 1st Curtain, which fires the pre-flash used to calculate the exposure before the shutter opens, followed by the main flash as soon as the shutter is completely open. This is the default mode, and you’ll generally perceive the pre-flash and main flash as a single burst. Alternatively, you can select 2nd Curtain, which fires the pre-flash as soon as the shutter opens, and then triggers the main flash in a second burst at the end of the exposure, just before the shutter starts to close. (If the shutter speed is slow enough, you may clearly see both the pre-flash and main flash as separate bursts of light.) This action allows photographing a blurred trail of light of moving objects with sharp flash exposures at the beginning and the end of the exposure. This type of flash exposure is slightly different from what some other cameras produce using 2nd Curtain.

If you have an external compatible Speedlite attached, you can also choose High-speed sync, which allows you to use shutter speeds faster than 1/250th second, using the External Flash Function Setting menu.

- Flash exposure compensation. You can use the Quick Control screen (press the Q button) and enter flash exposure compensation. If you’d rather adjust flash exposure using a menu, you can do that here. Select this option with the SET button, then dial in the amount of flash EV compensation you want using the directional buttons. The EV that was in place before you started to make your adjustment is shown as a blue indicator, so you can return to that value quickly. Press SET again to confirm your change, then press the MENU button twice to exit.

- Wireless functions. Additional choices appear below this entry when you’ve enabled wireless operation. If you’ve disabled wireless functions here, the other options don’t appear on the menu. I’m going to leave the explanation of these options for Chapter 12, which is an entire chapter dedicated to using the 90D’s wireless shooting capabilities.

Using Flash Mode

Here’s some additional detail on choosing the Flash Mode from the Built-In Flash menu. As mentioned earlier, you can select E-TTL II or Manual flash.

E-TTL II

You’ll leave Flash Mode at this setting most of the time. In this mode, the camera fires a pre-flash prior to the exposure, and measures the amount of light reflected to calculate the proper settings. As noted earlier, when you’ve selected the E-TTL II Flash mode, you can also choose Evaluative (Face Priority), Evaluative, or Average metering methods.

Manual Flash

Use this setting when you want to specify exactly how much light is emitted by the flash units, and don’t want the 90D’s E-TTL II exposure system to calculate the f/stop for you. When you activate this option, the two flash exposure compensation entries are replaced by internal and external flash output scales (the built-in and external flash units are represented by icons). You can select from 1/1 (full power) to 1/128th power for the built-in flash. A blue indicator appears under the previous setting, and a white indicator under your new setting, a reminder that you’ve chosen reduced power. Here are some situations where you might want to use manual flash settings:

- Close-ups. You’re shooting macro photos and the E-TTL II exposure is not precisely what you’d like. You can dial in exposure compensation or set the output manually. Close-up photos are problematic, because the power of the built-in flash may be too much (choose 1/128th power to minimize the output), or the reflected light may not be interpreted accurately by the through-the-lens metering system. Manual flash gives you greater control.

- Fill flash. Although E-TTL II can be used in full daylight to provide fill flash to brighten shadows, using manual flash allows you to tweak the amount of light being emitted in precise steps. Perhaps you want just a little more illumination in the shadows to retain a dramatic lighting effect without the dark portions losing all detail. Again, you can try using exposure compensation to make this adjustment, but I prefer to use manual flash settings. (See Figure 11.13.)

- Action stopping. The lower the power of the flash, the shorter the effective exposure. Use 1/128th power in a darkened room (so that there is no ambient light to contribute to the exposure and cause a “ghost” image) and you can end up with a “shutter speed” that’s the equivalent of 1/50000th second! Of course, with such a minimal amount of flash power, you need to be close to your subject.

Figure 11.13 You can fine-tune fill illumination by adjusting the output of your camera’s built-in flash manually. If shadows are too dark (left), fill flash can brighten them (right).

External Flash Function Setting

The Shooting 1 menu’s Flash Control entry has an External Flash Function Setting sub-menu that’s available only when an external flash is attached and powered up. The External Speedlite control menu offers six options (see Figure 11.14). The next sections will explain your choices.

Figure 11.14 The External Speedlite control menu has six options.

- Flash mode. This entry allows you to set the flash mode for the external flash, from E-TTL II, Manual flash, MULTI flash, CSP, and External A, External B. The last four options appear only when a flash compatible with those features is mounted, such as the Speedlite 600EX RT-II.

- Wireless functions. These functions are available when using wireless flash and will be explained in Chapter 12. This setting allows you to enable or disable wireless functions. You can choose Wireless: Off, Wireless: On (Optical Transmission), or Wireless: On (Radio Transmission). The last choice is shown and available only when using a radio-capable triggering device or flash, such as the 430EX III-RT or 600EX RT-II.

- Flash Zoom. Some flash units can vary their coverage to better match the field of view of your lens at a particular focal length. You can allow the external flash to zoom automatically, based on information provided, or manually, using a zoom button on the flash itself. This setting is disabled when using a flash like the Canon 270EX II, which does not have zooming capability. You can select Auto, in which case the camera will tell the flash unit the focal length of the lens, or choose individual focal lengths including 24mm, 28mm, 35mm, 50mm, 70mm, 80mm, and 105mm. The 600EX-RT offers an additional setting of 200mm.

- Shutter synchronization. As with the 90D’s internal flash, you can choose 1st Curtain, which, as I mentioned earlier, fires the flash as soon as the shutter is completely open (this is the default mode). Alternatively, you can select 2nd Curtain, which fires the flash as soon as the shutter opens, and then triggers a second flash at the end of the exposure, just before the shutter starts to close. If a compatible Canon flash, such as the Speedlite 430EX III or 600EX-RT is attached and turned on, you can also select High-speed sync. and shoot using shutter speeds faster than 1/250th second. HSS does not work in wireless mode, as I’ll explain in Chapter 12.

- Flash exposure compensation. You can add/subtract exposure compensation for the external flash unit, in a range of –3 to +3 EV. Dial in the amount of flash EV compensation you want using the directional buttons. The EV that was in place before you started to make your adjustment is shown as a blue indicator, so you can return to that value quickly.

- Flash exposure bracketing. Flash Exposure Bracketing (FEB) operates similarly to ordinary exposure bracketing, providing a series of different exposures to improve your chances of getting the exact right exposure, or to provide alternative renditions for creative purposes.

If you enable wireless flash, additional options appear in this menu (I’ll cover these in more detail in Chapter 12):

- Channel. All flashes used wirelessly can communicate on one of four channels. This setting allows you to choose which channel is used. Channels are especially helpful when you’re working around other Canon photographers; each can select a different channel so one photographer’s flash units don’t trigger those of another photographer.

- Master flash. You can enable or disable use of the external flash as the master controller for the other wireless flashes. When set to enable, the attached external flash is used as the master; when disabled, the external flash becomes a slave unit triggered by the 90D’s built-in flash.

- Flash Firing Group. Multiple flash units can be assigned to a group. This choice allows specifying which groups are triggered, A/B, A/B plus C, or All. The 600EX-RT offers additional groups when using radio control mode, Groups D and E.

- A:B fire ratio. If you select A/B or A/B plus C, this option appears, and allows you to set the proportionate outputs of Groups A and B, in ratios from 8:1 to 1:8, as explained in Chapter 12.

- Group C exposure compensation. If you select A/B plus C, this option appears, too, allowing you to set flash exposure compensation separately for Group C flashes.

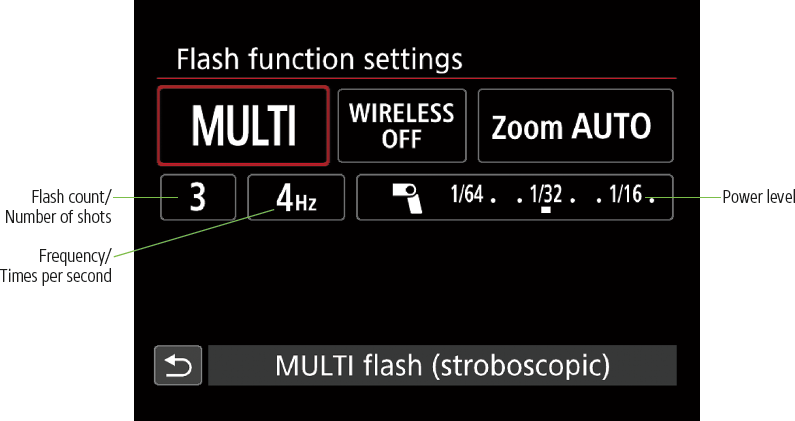

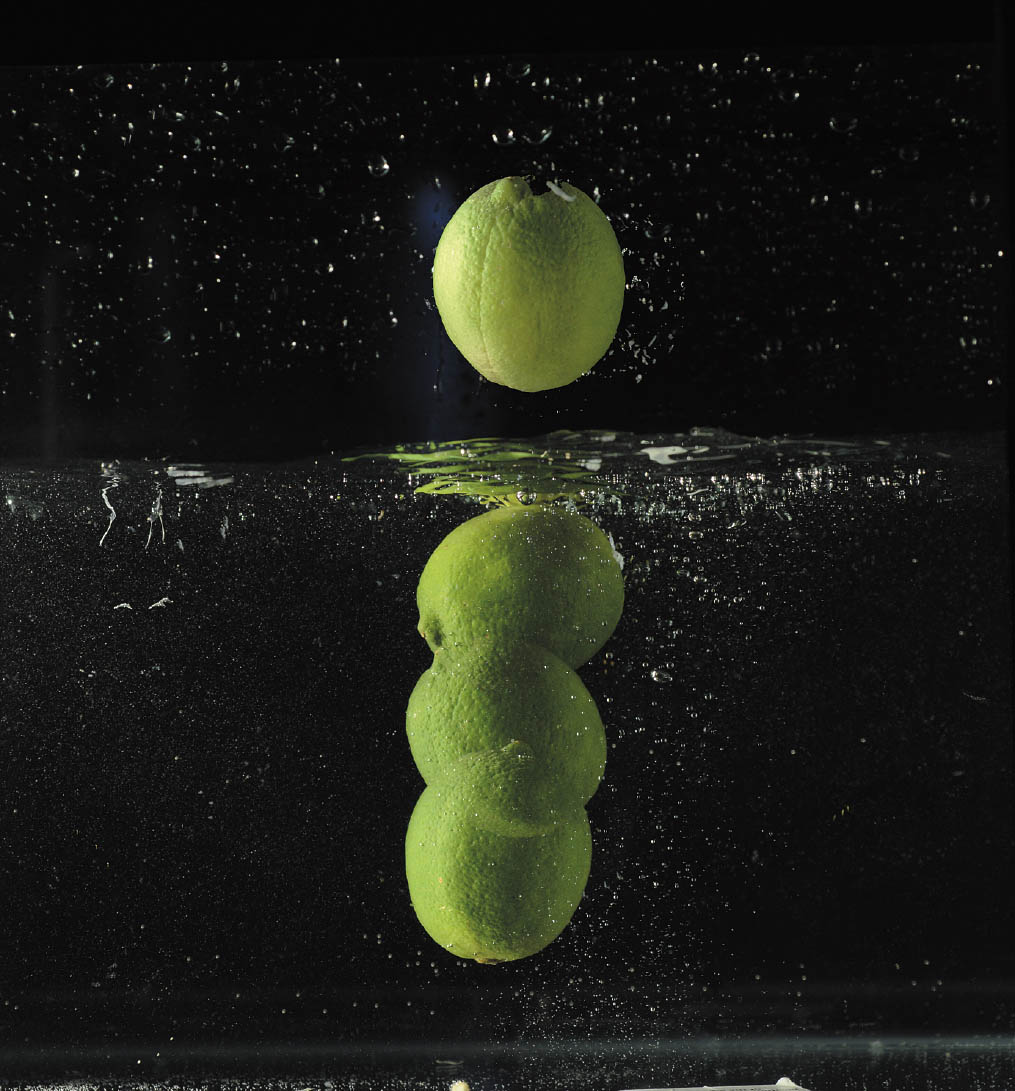

Learning about MULTI Flash

The MULTI flash setting, available with some flash units, makes it possible to shoot cool stroboscopic effects, with the flash firing several times in quick succession. You can use the capability to produce multiple images of moving objects to trace movement (say, your golf swing). When you’ve activated MULTI flash, three parameters appear on the External Flash Function Setting menu, as shown in Figure 11.15.

Figure 11.15 MULTI flash can be specified when an external flash is attached.

- Flash count/Number of shots. This setting determines the number of flashes in a given burst and can be set from 1 to 50 flashes.

- Frequency/Times per second. This figure specifies the number of bursts per second. With the built-in flash, you can choose (theoretically) 1 to 199 bursts per second. The actual number of flashes produced will be determined by your flash count (which turns off the flash after the specified number of flashes), flash output (higher output levels will deplete the available energy in your flash unit), and your shutter speed.

- Power level. Adjust the output of the flash for each burst, from 1/4 to 1/128th power.

These factors work together to determine the maximum number of flashes you can string together in a single shot. The exact number will vary, depending on your settings. MULTI flash can be used to get some interesting effects, as shown in Figure 11.16.

Figure 11.16 MULTI flash stroboscopic effect.

Continuous Shooting Priority

This feature was introduced with the Canon Speedlite EL-100, and it simplifies using compatible flash in continuous shooting mode. If your flash offers this mode, the flash output will be automatically decreased by one stop, and ISO sensitivity is set to Auto. These adjustments allow you to shoot continuously if you need to and conserve your flash’s battery power in both continuous and single-shot modes. Because of the adjustments the camera makes for you in this mode, you should check your ISO settings after you stop using the flash and reset them to your preferred values if necessary.

External Automatic/External Manual (Ext.A/Ext.M)

Some current Speedlites, such as the 600EX II-RT, and older units still in widespread use (like the EX-580), include a metering sensor on the flash itself. When you specify either of those choices, through-the-lens (E-TTL II) metering is disabled, and the flash’s external sensor will be used to measure exposure instead. You’ll find in most cases that E-TTL II metering is more accurate, and preferable for applications like balanced fill flash outdoors or balancing ambient light and flash indoors when using Av or Tv modes.

While these external metering modes are often considered obsolete, some find them useful, say, when removing the flash from the camera to illuminate backgrounds or other objects—including macro subjects—from an angle. The Speedlite still needs to be connected to the 90D with a cable, such as the Canon OC-E3, but you can position the flash anywhere the cable can stretch to.

Ext.A

Choose Ext.A in the 90D’s External Flash Function Setting menu or use the Mode button on the flash. You may have to check the Custom Functions settings on your flash to make sure the feature has not been disabled. When you press the shutter release halfway, the effective flash range is displayed. When you take a photo, the flash output is adjusted according to the aperture and ISO speed you’ve chosen.

Ext.M

In this mode, you must manually tell the flash unit the aperture and ISO speed set on the camera. This manual mode allows connecting the Speedlite to the 90D using the “dumb” PC terminal on the flash and a “dumb” PC/X terminal adapter mounted on the 90D’s flash shoe. The main reason you might want to use this type of connection is because PC/X cables are available in much longer lengths than the “intelligent” OC-E3 cable. It’s a stretch, but this feature is available if you need it.

Choose Ext.M in the 90D’s External Flash Function Setting menu or use the Mode button on the flash. Next, press the flash unit’s ISO button (Function Button 3) and aperture setting button (Function Button 4) and enter the sensitivity and f/stop set on the camera.

High-Speed Sync

High-speed sync is a special mode that allows you to synchronize an external flash (but not the built-in flash) at all shutter speeds, rather than just 1/250th second and slower. The entire frame is illuminated by a series of continuous bursts as the shutter opening moves across the sensor plane, so you do not end up with a horizontal black band, as shown earlier in Figure 11.7.

HSS is especially useful in three situations, all related to problems associated with high ambient light levels:

- Eliminate “ghosts” with moving images. When shooting with flash, the primary source of illumination may be the flash itself. However, if there is enough available light, a secondary image may be recorded by that light (as described under “Ghost Images” earlier in this chapter). If your main subject is not moving, the secondary image may be acceptable or even desirable. Indeed, the 90D has a provision for slow sync in its Night Portrait scene setting that allows using a slow shutter speed to record the ambient light and help illuminate dark backgrounds. But if your subject is moving, the secondary image creates a ghost image.

High-speed sync gives you the ability to use a higher shutter speed. If ambient light produces a ghost image at 1/250th second, upping the shutter speed to 1/500th or 1/1000th second may eliminate it.

Of course, HSS reduces the amount of light the flash produces. If your subject is not close to the camera, the waning illumination of the flash may force you to use a larger f/stop to capture the flash exposure. So, while shifting from 1/250th second at f/8 to 1/500th second at f/8 will reduce ghost images, if you switch to 1/500th second at f/5.6 (because the flash is effectively less intense), you’ll end up with the same ambient light exposure. Still, it’s worth a try.

- Improved fill flash in daylight. The 90D can use the built-in flash or an attached unit to fill in inky shadows—both automatically and using manually specified power ratios, as described earlier in this chapter. However, both methods force you to use a 1/250th second (or slower) shutter speed. That limitation can cause three complications.

First, in very bright surroundings, such as beach or snow scenes, it may be difficult to get the correct exposure at 1/250th second. You might have to use f/16 or a smaller f/stop to expose a given image, even at ISO 100. If you want to use a larger f/stop for selective focus, then you encounter the second problem—1/250th second won’t allow apertures wider than f/8 or f/5.6 under many daylight conditions at ISO 100. (See the discussion of fill flash with Aperture-priority in the next bullet.)

Finally, if you’re shooting action, you’ll probably want a shutter speed faster than 1/250th second, if at all possible under the current lighting. That’s because, in fill-flash situations, the ambient light (often daylight) provides the primary source of illumination. For many sports and fast-moving subjects, 1/500th second, or faster, is desirable. HSS allows you to increase your shutter speed and still avail yourself of fill flash. This assumes that your subject is close enough to your camera that the fill flash has some effect; forget about using fill and HSS with subjects a dozen feet away or farther. The flash won’t be powerful enough to have much effect on the shadows.

- When using fill flash with Aperture-priority. The difficulties of using selective focus with fill flash, mentioned earlier, become particularly acute when you switch to Av exposure mode. Selecting f/5.6, f/4, or a wider aperture when using flash is guaranteed to create problems when photographing close-up subjects, particularly at ISO settings higher than ISO 100. If you own an external flash unit, HSS may be the solution you are looking for.

ALL HSS, ALL THE TIME

If you are using a compatible flash unit, it’s safe to enable high-speed sync all the time. That’s because if you set the camera for 1/250th second or slower, the flash will fire normally at its set power output, just as if HSS were not enabled. But once you venture past 1/250th second to a faster shutter speed, the camera/flash combination is smart enough to use HSS. However, it’s your responsibility to remember that you’ve enabled high-speed sync, and realize that as you increase the shutter speed, the effective range of the flash is reduced. At 1/1000th second, the 600EX-RT is “good” out to about two feet from the camera. (Remember, HSS does not work in wireless mode, so the flash must be attached to the camera’s hot shoe.) At 1/4000th second, the flash will illuminate subjects no more than about one foot from the flash/camera.

To activate HSS using the 580EX II, which is the most used high-end Canon Speedlite, or 600EX-RT/600EX II-RT, just follow these steps:

- 1. Attach the flash. Mount/connect the external flash on the 90D, using the hot shoe or a cable. (HSS cannot be used in wireless mode, nor with a flash linked through an adapter that provides a PC/X terminal.)

- 2. Power up. Turn the flash and camera on.

- 3. Select HSS in the camera. Set the External Flash Function Setting in the camera to HSS as the 90D’s sync mode.

- Choose Flash Control in the Shooting 1 menu.

- Select External Flash Func. Setting.

- Navigate to the Shutter Sync. Entry, press SET, and choose High-Speed (at the far right of the list). Press SET again to confirm.

- 4. Choose HSS on the flash. Activate HSS (FP flash) on your attached external flash. With the 580EX II, press the High-speed sync button on the back of the flash unit (it’s the second from the right under the LCD). (See Figure 11.17.) With the 600EX-RT/600EX II-RT, press Function Button 4 (Sync), located at the far right of the row of four buttons just under the LCD.

- 5. Confirm HSS is active. The HSS icon will be displayed on the flash unit’s LCD (at the upper-left side with the 580EX II), and at bottom left in the 90D’s viewfinder. If you choose a shutter speed of 1/250th second or slower, the indicator will not appear in the viewfinder, as HSS will not be used at slower speeds.

- 6. View minimum/maximum shooting distance. Choose a distance based on the maximum shown in the line at the bottom of the flash’s LCD display (from 0.5 to 18 meters).

- 7. Shoot. Take the picture. To turn off HSS, press the button on the flash again. Remember that you can’t use MULTI flash or Wireless flash when working with High-speed sync.

Figure 11.17 Activate High-speed sync on the flash.

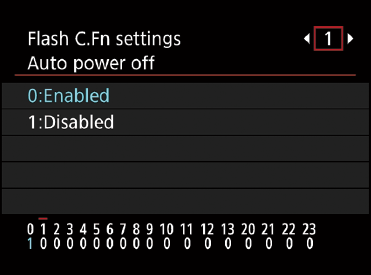

Flash C.Fn Settings

This menu entry produces a screen that allows you to set any available Custom Functions in your flash, from the camera. The functions available will depend on the C.Fn settings included in the flash unit. The EL-100 has only two Custom Functions, while the more top-of-the-line model EX600 II-RT, has 24 Custom Functions (see Figure 11.18). To set flash Custom Functions, rotate the QCD to choose the C.Fn number to be adjusted, then press SET. Rotate the Quick Control Dial again to choose from that function’s options, then press SET again to confirm.

Figure 11.18 Custom Functions for your Speedlite can be set from the camera’s Flash C.Fn menu.

Clear Settings

Select this menu entry, located at the bottom of the screen, and you’ll be asked if you want to change all the flash settings to their factory default values. You have two choices: Clear Flash Settings (the settings internal to the 90D) and Clear All Speedlite C.Fn’s, which returns all the attached Speedlite’s Custom Function settings to their factory defaults. The only exception is C.Fn-0: Distance Indicator Display, which will remain at its set value.

Working with External Electronic Flash

Once the capacitor is charged, the burst of light that produces the main exposure can be initiated by a signal from the 90D that commands the internal or connected flash units to fire. External strobes can be linked to the camera in several different ways:

- Camera-mounted/hardwired external dedicated flash. Units offered by Canon or other vendors that are compatible with Canon’s lighting system can be clipped onto the accessory “hot” shoe on top of the camera or linked through a wired system such as the Canon Off Shoe Camera Cord OC-E3.

- Wireless dedicated flash. A compatible unit can be triggered by signals produced by a pre-flash (before the main flash burst begins), which offers two-way communication between the camera and flash unit. The triggering flash can be the built-in flash, an external flash unit in Master mode, or a wireless non-flashing accessory, such as the Canon Speedlite Transmitter ST-E2 and radio-controlled wireless trigger, the Speedlite Transmitter ST-E3-RT, which each do nothing but “talk” to the external flashes. You’ll find more on this mode in Chapter 12.

- Wired, non-intelligent mode. If you connect a flash to a PC/X adapter attached to the hot shoe, you can use non-dedicated flash units, including studio strobes, through a non-intelligent camera/flash link that sends just one piece of information, one way: it tells a connected flash to fire. There is no other exchange of information between the camera and flash. The PC/X adapter can be used to link the 90D to studio flash units, manual flash, flash units from other vendors that can use a PC cable, or even Canon-brand Speedlites that you elect to connect to the 90D in “unintelligent” mode.

- Infrared/radio transmitter/receivers. Another way to link flash units to the 90D is through third-party wireless infrared or radio transmitters, like a PocketWizard, RadioPopper, or the Paul C. Buff CyberSync trigger. These are generally mounted on the accessory shoe of the camera and emit a signal when the 90D sends a command to fire through the hot shoe. The simplest of these function as a wireless dumb (PC/X-type) connector, with no other communication between the camera and flash (other than the instruction to fire). However, sophisticated units have their own built-in controls and can send additional commands to the receivers when connected to compatible flash units. I use one to adjust the power output of my Alien Bees studio flash from the camera, without the need to walk over to the flash itself.

- Simple slave connection. In the days before intelligent wireless communication, the most common way to trigger off-camera, non-wired flash units was through a slave unit. These can be small external triggers connected to the remote flash (or built into the flash itself) and set off when the slave’s optical sensor detects a burst initiated by the camera itself. When it “sees” the main flash (from the 90D’s attached external flash, or another flash), the slave flash units are triggered quickly enough to contribute to the same exposure. The main problem with this type of connection—other than the lack of any intelligent communication between the camera and flash—is that the slave may be fooled by any pre-flashes that are emitted by the other strobes, and fire too soon. Modern slave triggers have a special “digital” mode that ignores the pre-flash and fires only from the main flash burst.

Canon offers a broad range of accessory electronic flash units for the 90D. They can be mounted to the flash accessory shoe or used off-camera with a dedicated cord that plugs into the flash shoe to maintain full communications with the camera for all special features. (Non-dedicated flash units, such as studio flash, can be connected using a PC/X adapter.) They range from the Speedlite 600EX II-RT and Speedlite 580EX II, which can correctly expose subjects up to 24 feet away at f/11 and ISO 200, to the 270EX II, which is good out to 9 feet at f/11 and ISO 200. (You’ll get greater ranges at even higher ISO settings, of course.) There are also two electronic flash units specifically for specialized close-up flash photography.

I power my Speedlites with Panasonic Eneloop AA nickel metal hydride batteries. These are a special type of rechargeable battery with a feature that’s ideal for electronic flash use. The Eneloop cells, unlike conventional batteries, don’t self-discharge over relative short periods of time. Once charged, they can hold onto most of their juice for a year or more. That means you can stuff some of these into your Speedlite, along with a few spares in your camera bag, and not worry about whether the batteries have retained their power between uses. There’s nothing worse than firing up your strobe after not using it for a month and discovering that the batteries are dead.

Speedlite 600EX-RT/600EX II-RT

This flagship of the Canon accessory flash line (and most expensive at about $500) is the most powerful unit the company offers, with a GN of 197 and a manual/automatic zoom flash head that covers the full frame of lenses from 24mm wide angle to 200mm telephoto. (There’s a flip-down, wide-angle diffuser that spreads the flash to cover a 14mm lens’s field of view, too.) All angle specifications given by Canon refer to full-frame sensors, but this flash unit automatically converts its field of view coverage to accommodate the crop factor of the 90D and the other 1.6X crop Canon dSLRs. The latest 600EX II-RT has improved continuous flash firing rates (up to 2X faster with an optional CP-E4N battery pack).

The 600EX-RT/II-RT share basic features with the discontinued (but still widely used) 580EX II, described next, so I won’t repeat them here, because the typical veteran Canon owner is more likely to own multiple Speedlites.

The killer feature of this series is the wireless two-way radio communication between the camera and this flash (or ST-E3-RT wireless controller and the flash) at distances of up to 98 feet. You can link up to 15 different flash units with radio control, using five groups (A, B, C, D, and E), and no line-of-sight connection is needed. (You can hide the flash under a desk or in a potted plant.) With the latest Canon cameras having a revised “intelligent” hot shoe (which includes the 90D), a second 600EX-RT/600EX II-RT can be used to trigger a camera that also has a 600EX-RT/600EX II-RT mounted, from a remote location. That means you can set up multiple cameras equipped with multiple flash units to all fire simultaneously! For example, if you were shooting a wedding, you could photograph the bridal couple from two different angles, with the second camera set up on a tripod, say, behind the altar.

600EX (NON-RADIO)

If you see references to a 600EX model (non-RT), you’ll find that a version with the radio control crippled is sold only outside the USA in countries where obtaining permission to use the relevant radio spectrum is problematic.

The 600EX II-RT maintains backward compatibility with optical transmission used by earlier cameras. However, it’s a bit pricey for the average 90D owner, who is unlikely to be able to take advantage of all its features. If you’re looking for a high-end flash unit and don’t need radio control, I still recommend the Speedlite 580EX II (described next), which is still widely available and is the most-used high-end flash Canon has ever offered.

Remember that with the 600EX II-RT, you can’t use radio control and some other features unless you own at least two radio-controlled Speedlites, such as a 600EX II-RT or 430EX III-RT (described later) or one 600EX II-RT plus the ST-E3-RT, which costs about $300. Radio control is possible only between a camera that has a radio-capable flash or ST-E3-RT in the hot shoe, and an additional radio-capable flash or ST-E3-RT.

Custom Functions of the 600EX II-RT can be set using the 90D’s External Flash C.Fn Setting menu. Additional Personal Functions can be specified on the flash itself. The 90D-friendly functions include:

C.Fn-00 |

Distance indicator display (Meters/Feet) |

C.Fn-01 |

Auto power off (Enabled/Disabled) |

C.Fn-02 |

Modeling flash (Enabled-DOF preview button/Enabled-test firing button/Enabled-both buttons/Disabled) |

C.Fn-03 |

FEB Flash exposure bracketing auto cancel (Enabled/Disabled) |

C.Fn-04 |

FEB Flash exposure bracketing sequence (Metered > Decreased > Increased Exposure/Decreased > Metered > Increased Exposure) |

C.Fn-05 |

Flash metering mode (E-TTL II/E-TTL/TTL/External metering: Auto/External metering: Manual) |

C.Fn-06 |

Quickflash with continuous shot (Disabled/Enabled) |

C.Fn-07 |

Test firing with autoflash (1/32/Full power) |

C.Fn-08 |

AF-assist beam firing (Enabled/Disabled) |

C.Fn-09 |

Auto zoom adjusted for image/sensor size (Enabled/Disabled) |

C.Fn-10 |

Slave auto power off timer (60 minutes/10 minutes) |

C.Fn-11 |

Cancellation of slave unit auto power off by master unit (within 8 hours/within 1 hour) |

C.Fn-12 |

Flash recycling on external power (Use internal and external power/Use only external power) |

C.Fn-13 |

Flash exposure metering setting button (Speedlite button and dial/Speedlite dial only) |

Beep (Enable/Disable) |

|

C.Fn-21 |

Light distribution (Standard, Guide number priority, Even coverage) |

C.Fn-22 |

LCD panel illumination (On for 12 seconds, Disable, Always on) |

C.Fn-23 |

Slave flash battery check (AF-assist beam/Flash lamp, Flash lamp only) |

The Personal Functions available include the following. Note that you can set the LCD panel color to differentiate at a glance whether a given flash is functioning in Master or Slave mode.

P.Fn-01 |

LCD panel display contrast (Five levels of contrast) |

P.Fn-02 |

LCD panel illumination color: Normal (Green, Orange) |

P.Fn-03 |

LCD panel illumination color: Master (Green, Orange) |

P.Fn-04 |

LCD panel illumination color: Slave (Green, Orange) |

P.Fn-05 |

Color filter auto detection (Auto, Disable) |

P.Fn-06 |

Wireless button toggle sequence (Normal > Radio > Optical, Normal < > Radio, Normal < > Optical) |

P.Fn-07 |

Flash firing during linked shooting (Disabled, Enabled) |

Speedlite 580EX II