CONCEPT 5

Some Proteins Are Best Cooked Twice

While home cooks tend to think of recipes as either “stovetop” or “oven,” it’s different in restaurants. Professional chefs often move food back and forth from one heat source to the other—and not just for show. The stovetop is ideal for quick browning, but with heat from a single direction it’s difficult to cook food evenly and preserve moisture. One solution is to open the oven.

When preparing meat and other proteins, we all struggle to balance flavor development with moisture retention. As a result, sometimes the use of two cooking methods is absolutely necessary. There are a couple of solutions to explore.

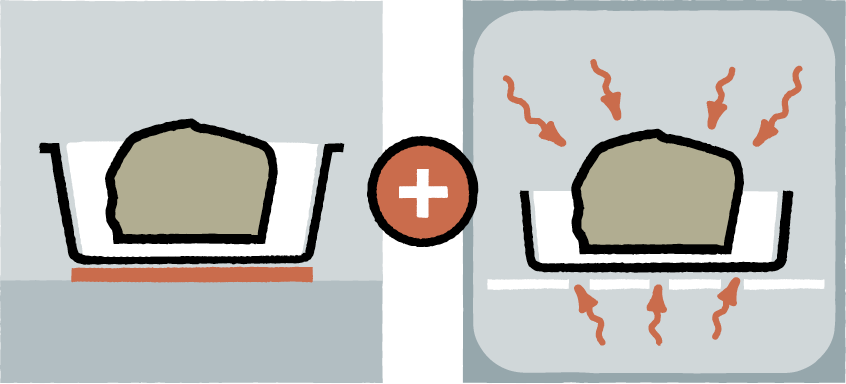

Sear and then roast is one. As we learned in the first concepts in this book, the high heat of the stovetop develops color and flavor, while the oven allows the meat’s interior to come up to temperature with ease. Coupling these techniques prevents scorching and excess moisture loss.

After all, an oven is a relatively inefficient heat conductor. A 12-inch conventional skillet set over medium-high heat on a gas burner will reach 400 degrees in less than five minutes while an identical pan heated indirectly by the air of a 400-degree oven will take 30 minutes to reach the same temperature. As a result, cooking vessels in the oven are generally cooler than those on the stovetop, and a cooler vessel means less heat transfer and therefore less moisture loss.

While it’s common to sear and then roast, it’s also possible to flip the order. Both techniques accomplish the same thing, but when cooking very thick steaks and chops it makes sense to roast before the sear. Why?

Let’s start with basic thermodynamics: When a 40-degree steak is placed in a 400-degree skillet, the temperature of the pan drops significantly. Until the temperature recovers to at least 300 degrees (necessary for rapid Maillard reaction), little browning will occur. Therefore, it can take more than four minutes per side to form a good crust on a cold, thick steak—during which time the meat beneath the surface is robbed of moisture as it swings way above 160 degrees. It’s difficult to make the pan hotter than 450 degrees when cooking with oil due to its smoke point, but you can change the temperature of the meat.

Warming meat in an oven before searing accomplishes three things. The meat doesn’t cool down a hot pan the way it would straight from the refrigerator. As a result, the pan stays hot enough for browning to commence almost immediately. Second, the oven-warming period evaporates some surface moisture, so there’s less to be converted to steam before the browning process can begin. With less time in the pan, less heat is absorbed, and the meat just below the surface is not overcooked. Finally, the gentle heat of the slow warming stage in the oven activates enzymes called cathepsins, which produce more tender meat (see concept 6 for more on this topic).

To understand how cooking method affects moisture loss, we cooked boneless, skinless chicken breasts on the stovetop and compared moisture loss in these samples to moisture loss in identical breasts cooked to the same internal temperature, but seared on the stovetop and finished in the oven. We placed three 8-ounce breasts in a large skillet (nonstick, so we could see the results on the chicken, not the pan), set it over medium-high heat with 2 teaspoons of vegetable oil, and seared the chicken until it registered 160 degrees, flipping the breasts halfway through cooking. We also seared three more 8-ounce chicken breasts using the same method, but we transferred the skillet to a 400-degree oven after flipping. We repeated the tests and averaged the results.

THE RESULTS

First off, we noticed significant visual differences. The chicken on the stovetop was much darker in color (verging on burnt) than the chicken that spent half its time in the oven. This was due to the temperature of the skillet, which we tracked for both cooking methods. While the skillet that moved from the stovetop to the oven never got above 300 degrees, the skillet on the stovetop continued to climb to over 450 degrees. Interestingly, both samples reached 160 degrees in roughly 20 minutes. This is because while the bottom of the stovetop samples received intense heat from the skillet, the side not in contact with the pan received little heat. In contrast, the samples cooked partially in the oven absorbed moderate heat from all sides. So even though the oven was set to 400 degrees, the heat transfer on the stovetop was much more focused and efficient, thus the greater degree of browning. Browning, however, is only half the story.

When tasters sampled the chicken, they found samples cooked on the stovetop more flavorful. But tasters also noted that this chicken seemed drier and tougher than the chicken that finished cooking in the oven.

The before-and-after weights told the story here. Moisture loss was about 25 percent in the breasts cooked on the stovetop but 19 percent in those cooked partially on the stovetop and partially in the oven. These percentages translate into an extra tablespoon of juices in each of the combination-cooked breasts.

THE EFFECT OF COOKING METHOD ON MOISTURE LOSS IN CHICKEN BREASTS

SEARED ON STOVETOP

Weight before cooking: 7.18 ounces

Weight after cooking: 5.36 ounces

Moisture loss: 25.35%

SEARED ON STOVETOP, ROASTED IN OVEN

Weight before cooking: 7.17 ounces

Weight after cooking: 5.82 ounces

Moisture loss: 18.8%

THE TAKEAWAY

Searing is a great way to add flavor because it delivers focused heat quickly and efficiently and thus promotes a lot of browning in a minimum of time. But it also causes a lot of moisture loss. Roasting small cuts yields food with spotty browning and flavor development but higher levels of moisture retention. Combining the methods offers the best of both worlds.

BROWNING THEN ROASTING AT WORK

CHICKEN PARTS

Browning and then roasting is the ideal way to cook chicken parts, which are very thick and must be cooked to a fairly high internal temperature of 160 degrees to kill bacteria. Chicken parts need at least 20 minutes of cooking time, if not more. After all, the bones slow down the transfer of heat while the skin needs time to crisp (for more on cooking meat that contains bones, see concept 10). You could roast chicken parts entirely in the oven, but the skin won’t become super-crisp. You need the stovetop for that. But if you cook bone-in parts solely on the stovetop, be prepared for a lot of splattering and fat. In this recipe, the blast of heat at the outset renders fat and crisps up the skin before the operation—skillet and all—is moved to the oven, where you can cook the chicken as long as necessary without the risk of splattering or scorching.

PAN-ROASTED CHICKEN BREASTS WITH SAGE-VERMOUTH SAUCE

SERVES 4

We prefer to split whole chicken breasts ourselves because store-bought split chicken breasts are often sloppily butchered. However, if you prefer to purchase split chicken breasts, try to choose 10- to 12-ounce pieces with skin intact. If using kosher chicken, do not brine in step 1, and season with salt as well as pepper. For more information on brining, see concept 11.

|

CHICKEN |

|

|

½ |

cup salt |

|

2 |

(1½-pound) bone-in whole chicken breasts, split through breastbone and trimmed |

|

|

Pepper |

|

1 |

tablespoon vegetable oil |

|

SAUCE |

|

|

1 |

large shallot, minced |

|

¾ |

cup low-sodium chicken broth |

|

½ |

cup dry vermouth or dry white wine |

|

4 |

fresh sage leaves, torn in half |

|

3 |

tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into 3 pieces and chilled |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

1. FOR THE CHICKEN: Dissolve salt in 2 quarts cold water in large container. Submerge chicken in brine, cover, and refrigerate for 30 minutes to 1 hour. Remove chicken from brine and pat dry with paper towels. Season chicken with pepper.

2. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 450 degrees. Heat oil in 12-inch ovensafe skillet over medium-high heat until just smoking. Carefully lay chicken pieces skin side down in skillet and cook until well browned, 6 to 8 minutes. Flip chicken and continue to brown lightly on second side, about 3 minutes.

3. Flip chicken skin side down and transfer skillet to oven. Roast until chicken registers 160 degrees, 15 to 20 minutes.

4. Using potholder (skillet handle will be very hot), remove skillet from oven. Transfer chicken to serving platter and let rest while making sauce.

5. FOR THE SAUCE: Being careful of hot skillet handle, pour off all but 1 teaspoon fat from pan, add shallot, and cook over medium-high heat until softened, about 2 minutes. Stir in broth, vermouth, and sage, scraping up any browned bits. Bring to simmer and cook until liquid is slightly thickened and measures about ¾ cup, about 5 minutes. Stir in any accumulated chicken juices, return to simmer, and cook for 30 seconds.

6. Off heat, remove sage leaves and whisk in butter, 1 piece at a time. Season with salt and pepper to taste, spoon sauce over chicken, and serve.

PAN-ROASTED CHICKEN BREASTS WITH SWEET-TART RED WINE SAUCE

This sauce is a variation on the Italian sweet-sour combination called agrodolce.

Add 1 tablespoon sugar and ¼ teaspoon pepper along with chicken broth. Replace vermouth with ¼ cup each red wine and red wine vinegar and replace sage with 1 bay leaf.

PAN-ROASTED CHICKEN BREASTS WITH ONION AND ALE SAUCE

Brown ale gives this sauce a nutty, toasty, bittersweet flavor. Newcastle Brown Ale and Samuel Smith Nut Brown Ale are good choices.

Substitute ½ onion, sliced very thin, for shallot and cook onion until softened, about 3 minutes. Add 1 bay leaf and 1 teaspoon brown sugar along with chicken broth. Replace vermouth with brown ale and sage with 1 sprig fresh thyme. Add ½ teaspoon cider vinegar along with salt and pepper.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Pan-roasting is a great way to cook chicken parts. In the oven, the skin never seems to crisp up enough. That’s because chicken parts cook much faster than a whole bird. Our solution is simple: Brown chicken parts in a skillet until the fat has rendered and the skin is really crisp, then transfer the skillet to the oven so the chicken can finish cooking through.

START SKIN SIDE DOWN The skin benefits the most from the searing portion of the recipe, so make sure the chicken goes into the pan skin side down. You want to render as much fat as possible from the skin and jump-start the browning process—and the stovetop, rather than the oven, is the place to get this done.

PUT SKIN SIDE DOWN AGAIN Once the skin is browned, we flip the chicken and sear it lightly on the second side. We then flip the chicken skin side down and put the skillet in the oven. Keeping the skin in direct contact with the hot skillet ensures that the skin emerges crackling crisp from the oven. Once the hot skillet is placed in the oven the skillet will begin to cool down to the same temperature as the oven, slowing the cooking process and reducing the loss of moisture.

DON’T TOUCH THAT PAN Once the chicken is done, it can be set aside on a platter and you can prepare a pan sauce based on the flavorful browned bits in the pan. Just be careful—the skillet handle is very, very hot. Since most cooks are accustomed to holding the skillet handle when it sits on the stovetop, we suggest leaving a potholder on the handle to remind yourself of the risk. Just make sure the potholder is well away from the burner: You don’t want to prevent one problem but cause another.

USE THE FOND The Maillard reaction is the source of deep flavors in meat (see concept 2). Some of the browned bits of meat end up sticking to the pan. The French call these browned bits fond, and they are a source of great flavor in quick pan sauces. Once the chicken has been removed from the pan, you can sauté an aromatic (shallot, garlic, or onion) and then add liquid (broth, wine, cider, or beer) and scrape the pan bottom with a wooden spoon to loosen those browned bits. The fond will dissolve into the sauce, adding complexity and depth. The liquid is reduced to concentrate the flavors of the sauce, and a little butter is whisked into the reduced sauce to give it some body.

ORANGE-HONEY GLAZED CHICKEN BREASTS

SERVES 4

We prefer to split whole chicken breasts ourselves because store-bought split chicken breasts are often sloppily butchered. However, if you prefer to purchase split chicken breasts, try to choose 10- to 12-ounce pieces with skin intact. When reducing the glaze in step 4, remember that the skillet handle will be hot; use a potholder. If the glaze looks dry during baking, add up to 2 tablespoons of juice to the pan. If your skillet is not ovensafe, brown the chicken breasts and reduce the glaze as instructed, then transfer the chicken and glaze to a 13 by 9-inch baking dish and bake (don’t wash the skillet). When the chicken is fully cooked, transfer it to a plate to rest and scrape the glaze back into the skillet to be reduced.

|

1½ |

cups plus 2 tablespoons orange juice (4 oranges) |

|

1⁄3 |

cup light corn syrup |

|

3 |

tablespoons honey |

|

1 |

tablespoon Dijon mustard |

|

1 |

tablespoon distilled white vinegar |

|

1⁄8 |

teaspoon red pepper flakes |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

½ |

cup all-purpose flour |

|

2 |

(1½-pound) whole bone-in chicken breasts, split through breastbone and trimmed |

|

2 |

tablespoons vegetable oil |

|

1 |

shallot, minced |

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 375 degrees. Whisk 1½ cups orange juice, corn syrup, honey, mustard, vinegar, pepper flakes, 1⁄8 teaspoon salt, and 1⁄8 teaspoon pepper together in medium bowl. Place flour in shallow dish. Pat chicken dry with paper towels and season with salt and pepper. Working with 1 chicken breast at a time, coat chicken with flour, patting off excess.

2. Heat oil in ovensafe 12-inch skillet over medium heat until shimmering. Add chicken breasts skin side down; cook until well browned, 8 to 14 minutes, reducing heat if pan begins to scorch. Flip chicken skin side up and lightly brown other side, about 5 minutes. Transfer chicken to plate.

3. Pour off all but 1 teaspoon fat from pan. Add shallot and cook until softened, 1 to 2 minutes. Increase heat to high and add orange juice mixture. Simmer, stirring occasionally, until syrupy and reduced to 1 cup (heatproof spatula should leave slight trail when dragged through glaze), 6 to 10 minutes. Remove skillet from heat and tilt to one side so glaze pools in corner of pan. Using tongs, roll each chicken breast in pooled glaze to coat evenly and place skin side down in skillet.

4. Transfer skillet to oven and bake until chicken registers 160 degrees, 25 to 30 minutes, turning chicken skin side up halfway through cooking. Transfer chicken to platter and let rest for 5 minutes. Return skillet to high heat (be careful—handle will be very hot) and cook glaze, stirring constantly, until thick and syrupy, about 1 minute. Remove pan from heat and whisk in remaining 2 tablespoons orange juice. Spoon 1 teaspoon glaze over each breast and serve, passing remaining glaze at table.

APPLE-MAPLE GLAZED CHICKEN BREASTS

Substitute apple cider for orange juice and 2 tablespoons maple syrup for honey.

PINEAPPLE–BROWN SUGAR GLAZED CHICKEN BREASTS

Substitute pineapple juice for orange juice and 2 tablespoons brown sugar for honey.

This recipe is traditionally prepared entirely in the oven. The skin never really becomes crisp and the glaze does not adhere very well. Using the skillet accomplishes two things—it renders fat quickly from the skin so it becomes browned and crisp, and it allows the glaze to reduce and thicken both before and after the roasting portion of this recipe.

FLOUR THE CHICKEN In general, we don’t flour meat before browning it. For instance, when browning meat for stew, we find that flour interferes with the complex taste of browned meat (instead you taste browned flour). In this recipe, however, the flour gives the chicken breasts a thin, crisp crust that serves as a good grip for the glaze.

REALLY RENDER THE FAT Cooking the chicken breasts skin side down over medium heat for 8 to 14 minutes gives the fat plenty of time to render and ensures that the skin will be crisp, even when glazed.

FORGET SUGARY GLAZES Most glazed chicken recipes rely on jam, honey, brown sugar, or maple syrup as the base for the glaze. The results are predictably sweet. We prefer using orange juice, which we reduce in the skillet once the chicken has been browned and set aside. A little honey, along with some Dijon mustard, vinegar, and red pepper flakes, creates a complex glaze with pantry ingredients. We also reserve some orange juice and add it to the finished glaze for a final hit of fresh orange flavor.

USE CORN SYRUP TO ADD MOISTURE While we dislike glazes that are all sweetener, we need something to thicken our glaze. A little honey helps, but adding more honey makes the glaze saccharine. We experimented with other sweeteners and tasters proclaimed corn syrup the winner. It turns out that corn syrup contains about half as much sugar as other sweeteners. Also, the sweeteners in corn syrup are mostly glucose and larger sugar molecules that are much less sweet than table sugar. An added benefit—when we added corn syrup to the glaze the chicken seemed moister. The concentrated glucose in corn syrup has an affinity for water, which means it helps to hold moisture in the glaze, making the overall dish seem juicier. That same glucose also thickens and adds a gloss to the glaze.

BROWNING THEN ROASTING AT WORK

FISH STEAKS

Most fish can be cooked completely on the stovetop. But if you have large halibut steaks, weighing 1¼ pounds and measuring 1½ inches thick, the exterior of the fish will dry and burn long before the interior comes up to 140 degrees, the temperature to which white fish are best cooked. A combination cooking method is ideal. We use a similar technique when preparing the Skillet-Roasted Fish Fillets.

PAN-ROASTED HALIBUT STEAKS

SERVES 4 TO 6

Prepare the vinaigrette (recipe follows) before cooking the fish. Even well-dried fish can cause the hot oil in the pan to splatter. You can minimize splattering by laying the halibut steaks in the pan gently and putting the edge closest to you in the pan first so that the far edge falls away from you. Make sure to cut off the cartilage at each end of the steaks to ensure that they will fit neatly in the pan and diminish the likelihood that the small bones located there will wind up on dinner plates.

|

2 |

(1¼-pound) skin-on full halibut steaks, 1¼ inches thick and 10 to 12 inches long |

|

2 |

tablespoons olive oil |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

1 |

recipe Chunky Cherry Tomato–Basil Vinaigrette (recipe follows) |

1. Rinse halibut steaks, dry well with paper towels, and trim cartilage from both ends. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 425 degrees. When oven reaches 425 degrees, heat oil in 12-inch ovenproof skillet over high heat until oil just begins to smoke.

2. Meanwhile, sprinkle both sides of halibut steaks with salt and pepper. Reduce heat to medium-high and swirl oil in pan to distribute; carefully lay steaks in pan and sear, without moving them, until spotty brown, about 4 minutes. (If steaks are thinner than 1¼ inches, check browning at 3½ minutes; thicker steaks of 1½ inches may require extra time, so check at 4½ minutes.) Off heat, flip steaks using 2 spatulas.

3. Transfer skillet to oven and roast until steaks register 140 degrees, flakes loosen, and flesh is opaque when checked with tip of paring knife, about 9 minutes (thicker steaks may take up to 10 minutes). Remove skillet from oven. Remove skin from cooked steaks and separate each quadrant of meat from bones by slipping spatula or knife gently between them. Transfer fish to warm platter and serve drizzled with vinaigrette.

CHUNKY CHERRY TOMATO–BASIL VINAIGRETTE

MAKES ABOUT 1½ CUPS, ENOUGH FOR 1 RECIPE PAN-ROASTED HALIBUT STEAKS

|

6 |

ounces cherry or grape tomatoes, quartered |

|

¼ |

teaspoon salt |

|

¼ |

teaspoon pepper |

|

6 |

tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil |

|

3 |

tablespoons lemon juice |

|

2 |

shallots, minced |

|

2 |

tablespoons minced fresh basil |

Mix tomatoes with salt and pepper in medium bowl; let stand until juicy and seasoned, about 10 minutes. Whisk oil, lemon juice, shallots, and basil together in small mixing bowl, pour over tomatoes, and toss to combine.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Halibut steaks this big will become very dry if cooked strictly on the stovetop. Roasting the fish produces moister results but there’s not enough time for browning. The stovetop part of this recipe browns the fish and builds flavor, while the oven portion of the recipe finishes cooking the fish through while preserving as much moisture as possible.

BROWN JUST ONE SIDE Even with its stint in the oven, we found that the fish dried out if we browned both sides. Instead, we browned just one side of the fish, flipped the steaks, and then immediately transferred the skillet to the oven, letting the second side brown more slowly in the oven, where the rate of moisture loss was lessened. Make sure to use two—not one—thin metal spatulas to flip the fish, and make sure to use 2 tablespoons of oil to prevent the fish from sticking.

MAKE A SEPARATE SAUCE While beef steaks will create significant fond in a skillet, the proteins in fish don’t create fond. Unlike beef, fish contains very little natural glucose, which is required to undergo the browning reaction with proteins. As a result, there’s no benefit to making a pan sauce. We prefer to make something more potent, like a chunky vinaigrette. If you prefer, serve the pan-roasted fish with your favorite compound butter.

BAKING THEN BROWNING AT WORK

STEAKS AND CHOPS

For steaks and chops in excess of 1½ inches we like this method because it raises the temperature of the meat before it is seared. Given the different final temperatures desired, 120 to 140 degrees for beef and 145 to 150 for pork, the steaks spend less time in the oven than the chops but the effect is the same.

PAN-SEARED THICK-CUT STRIP STEAKS

SERVES 4

Rib eye or filet mignon of similar thickness can be substituted for strip steaks. If using filet mignon, buying a 2-pound center-cut tenderloin roast and portioning it into four 8-ounce steaks yourself will produce more consistent results. If using filet mignon, increase the oven time by about five minutes. When cooking lean strip steaks (without an external fat cap) or filet mignon, add an extra tablespoon of oil to the pan.

|

2 |

(1-pound) boneless strip steaks, 1½ to 1¾ inches thick, trimmed |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

1 |

tablespoon vegetable oil |

|

1 |

recipe Red Wine–Mushroom Pan Sauce (optional) (recipe follows) |

1. Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 275 degrees. Pat steaks dry with paper towels. Cut each steak in half vertically to create four 8-ounce steaks. Season steaks with salt and pepper; using hands, gently shape into uniform thickness. Place steaks on wire rack set in rimmed baking sheet; transfer baking sheet to oven. Cook until meat registers 90 to 95 degrees (for rare to medium-rare), 20 to 25 minutes, or 100 to 105 degrees (for medium), 25 to 30 minutes.

2. Heat oil in 12-inch skillet over high heat until smoking. Place steaks in skillet and sear until well browned and crusty, 1½ to 2 minutes, lifting once halfway through cooking to redistribute fat underneath each steak. (Reduce heat if fond begins to burn.) Using tongs, turn steaks over and cook until well browned on second side, 2 to 2½ minutes. Transfer steaks to clean wire rack and reduce heat under pan to medium. Use tongs to stand 2 steaks on their sides. Holding steaks together, return to skillet and sear on all edges until browned, about 1½ minutes. Repeat with remaining 2 steaks.

3. Return steaks to wire rack and let rest, loosely tented with aluminum foil, for about 10 minutes. If desired, cook sauce in now-empty skillet. Arrange steaks on individual plates and spoon sauce, if using, over steaks; serve.

RED WINE–MUSHROOM PAN SAUCE

MAKES ABOUT 1 CUP, ENOUGH FOR 1 RECIPE PAN-SEARED THICK-CUT STRIP STEAKS

Prepare all the ingredients for the pan sauce while the steaks are in the oven; the sauce can be cooked while the steaks are resting.

|

1 |

tablespoon vegetable oil |

|

8 |

ounces white mushrooms, trimmed and sliced thin |

|

1 |

small shallot, minced |

|

1 |

cup dry red wine |

|

½ |

cup low-sodium chicken broth |

|

1 |

tablespoon balsamic vinegar |

|

1 |

teaspoon Dijon mustard |

|

2 |

tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into 4 pieces and chilled |

|

1 |

teaspoon minced fresh thyme |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

Pour off fat from skillet in which steaks were cooked. Heat oil over medium-high heat until just smoking. Add mushrooms and cook, stirring occasionally, until beginning to brown and liquid has evaporated, about 5 minutes. Add shallot and cook, stirring frequently, until beginning to soften, about 1 minute. Increase heat to high; add wine and broth, scraping bottom of skillet with wooden spoon to loosen any browned bits. Simmer rapidly until liquid and mushrooms are reduced to 1 cup, about 6 minutes. Add vinegar, mustard, and any accumulated steak juices; cook until thickened, about 1 minute. Off heat, whisk in butter and thyme; season with salt and pepper to taste. Spoon sauce over steaks and serve immediately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

When you’re cooking a 1-inch steak, the most likely problem is the crust, not the interior, which is why starting with a cold piece of meat is an advantage. (It gives you more time for a crust to form.) But with a thick steak, the problem is just the opposite. It will take a long, long time for the interior of a mammoth 1¾-inch steak to reach 130 degrees. Warming the steaks in the oven jump-starts this process while minimizing internal moisture loss and promoting even cooking from edge to center.

COOK LOW AND SLOW FOR TENDERNESS We noticed that, in addition to being evenly cooked, steaks prepared this way were especially tender. It turns out that meat contains active enzymes called cathepsins, which break down connective tissues over time, increasing tenderness (a fact that is demonstrated to great effect in dry-aged meat). As the temperature of the meat rises, these enzymes work faster and faster until they reach 122 degrees, where all action stops. While our steaks are slowly heating up, the cathepsins are working overtime, in effect “aging” and tenderizing our steaks within half an hour. When thick steaks are cooked by conventional methods, their final temperature is reached much more rapidly, denying the cathepsins the time they need to properly do their job. (For more about cathepsins, see concept 6.)

SEAR ON THE SIDES While most recipes instruct the cook to sear steaks on both flat sides, we found it beneficial to sear the steaks on their edges as well. We use a pair of tongs to hold two steaks at a time on their edges in the pan. The extra browning adds flavor and doesn’t overheat the steaks because the steaks are being rotated in the pan and don’t spend very long in any one place.

PAN-SEARED THICK-CUT PORK CHOPS

SERVES 4

Buy chops of similar thickness so that they cook at the same rate. If using table salt, sprinkle each chop with ½ teaspoon salt. We prefer the flavor of natural chops over that of enhanced chops (which have been injected with a salt solution and various sodium phosphate salts to increase moistness and flavor), but if processed pork is all you can find, skip the salting step below.

|

4 |

(12-ounce) bone-in pork rib chops, 1½ inches thick, trimmed |

|

|

Kosher salt and pepper |

|

1–2 |

tablespoons vegetable oil |

|

1 |

recipe pan sauce (recipes follow) |

1. Pat chops dry with paper towels. Using sharp knife, cut 2 slits, about 2 inches apart, through outer layer of fat and silverskin. Sprinkle entire surface of each chop with 1 teaspoon salt. Place chops on wire rack set in rimmed baking sheet and let stand at room temperature for 45 minutes. Meanwhile, adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 275 degrees.

2. Season chops with pepper; transfer baking sheet to oven. Cook until chops (away from bone) register 120 to 125 degrees, 30 to 45 minutes.

3. Heat 1 tablespoon oil in 12-inch skillet over high heat until smoking. Place 2 chops in skillet and sear until well browned and crusty, 1½ to 3 minutes, lifting once halfway through cooking to redistribute fat underneath each chop. (Reduce heat if browned bits in pan bottom start to burn.) Using tongs, turn chops over and cook until well browned on second side, 2 to 3 minutes. Transfer chops to plate and repeat with remaining 2 chops, adding 1 tablespoon oil if pan is dry.

4. Reduce heat to medium. Use tongs to stand 2 pork chops on their sides. Holding chops together with tongs, return to skillet and sear sides of chops (with exception of bone side) until browned and chops register 145 degrees, about 1½ minutes. Repeat with remaining 2 chops. Let chops rest, tented loosely with aluminum foil, for 10 minutes while preparing sauce.

GARLIC AND THYME PAN SAUCE

MAKES ½ CUP, ENOUGH FOR 1 RECIPE PAN-SEARED THICK-CUT PORK CHOPS

|

1 |

large shallot, minced |

|

2 |

garlic cloves, minced |

|

¾ |

cup low-sodium chicken broth |

|

½ |

cup dry white wine |

|

¼ |

teaspoon white wine vinegar |

|

1 |

teaspoon minced fresh thyme |

|

3 |

tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into 3 pieces and chilled |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

Pour off all but 1 teaspoon fat from pan used to cook chops and return pan to medium heat. Add shallot and garlic and cook, stirring constantly, until softened, about 1 minute. Add broth and wine, scraping pan bottom to loosen browned bits. Simmer until reduced to ½ cup, 6 to 7 minutes. Off heat, stir in vinegar and thyme, then whisk in butter, 1 tablespoon at a time. Season with salt and pepper to taste and serve with chops.

CILANTRO AND COCONUT PAN SAUCE

MAKES ½ CUP, ENOUGH FOR 1 RECIPE PAN-SEARED THICK-CUT PORK CHOPS

|

1 |

large shallot, minced |

|

1 |

tablespoon grated fresh ginger |

|

2 |

garlic cloves, minced |

|

¾ |

cup coconut milk |

|

¼ |

cup low-sodium chicken broth |

|

1 |

teaspoon sugar |

|

¼ |

cup minced fresh cilantro |

|

2 |

teaspoons lime juice |

|

1 |

tablespoon unsalted butter |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

Pour off all but 1 teaspoon fat from pan used to cook chops and return pan to medium heat. Add shallot, ginger, and garlic and cook, stirring constantly, until softened, about 1 minute. Add coconut milk, broth, and sugar, scraping pan bottom to loosen browned bits. Simmer until reduced to ½ cup, 6 to 7 minutes. Off heat, stir in cilantro and lime juice, then whisk in butter. Season with salt and pepper to taste and serve with chops.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

The oven-then-searing method is especially beneficial with pork chops today because over the years they have become so lean. (Today’s pork is at least 30 percent leaner than pork sold in the 1980s.) Overcooking pork, even slightly, yields tough results. And the window for doneness is quite narrow—lean pork chops are best cooked to 145 to 150 degrees. Also, because pork must be cooked to a higher internal temperature than beef, heat distribution is even more inequitable, especially in thick chops.

BUY BONE-IN RIB CHOPS You can generally find four different cuts of pork chops: sirloin, blade, center-cut, and rib loin. Sirloin chops, cut from the hip end of the pig, are tough, dry, and bland. For this recipe, we also decided against blade chops (cut from near the shoulder), which contain a fair amount of connective tissue and fat. Although the fat promises a juicy, flavorful chop, the connective tissue requires a long, moist cooking method to become tender. After comparing center-cut chops (cut from the center of the loin) and rib loin chops (cut from the rib section), we decided on the latter, preferring their meaty texture and slightly higher fat content. We opted to leave the bone in because it acts as an insulator and helps the chops cook gently while its fat helps to baste the meat as it cooks (see concept 10).

KEEP THEM FLAT Pork often comes covered with a thin membrane called silverskin. This membrane contracts faster than the rest of the meat, causing buckling and leading to uneven cooking. Cutting two slits about two inches apart in the silverskin around the edges of the chops prevents this problem. Make sure to cut through the fat and underlying silverskin.

SALT FOR FLAVOR Salting the pork chops draws out moisture via osmosis that, 45 minutes later, is pulled back into the meat, producing juicy, well-seasoned chops. Likewise this salt dissolves some of the meat proteins, making them more effective at holding moisture during cooking. (See concept 12 for more on salting meat.)

ROAST, THEN SEAR Cooking the salted chops in a gentle oven and then searing them in a smoking-hot pan has several advantages. First, chops cooked via this method are supremely tender because we keep them at a lower temperature for about 20 minutes longer than conventional sautéing or roasting methods do. This is in part because low-temperature enzymes called cathepsins (concept 6) are at work, breaking down proteins such as collagen and helping to tenderize the meat. Second, the gentle roasting dries the exterior of the meat, creating a thin, arid layer that turns into a gratifyingly crisp crust when seared.

BAKING THEN BROWNING AT WORK

BEEF TENDERLOIN

Beef tenderloin is extremely tender but fairly bland. As a result, it’s important to get a really good crust on the exterior. The problem is that it is very lean (that’s why it’s bland) and can easily dry out. Most cooks either sacrifice the browned crust (for a perfectly cooked interior) or live with a thick gray band of overcooked meat just below a nice brown crust. Baking then browning lets you have the best of both worlds—meat that is rosy pink from the edge to the center as well as a nice brown crust.

ROAST BEEF TENDERLOIN

SERVES 4 TO 6

Ask your butcher to prepare a trimmed center-cut Châteaubriand from the whole tenderloin, as this cut is not usually available without special ordering. If you are cooking for a crowd, this recipe can be doubled to make two roasts. Sear the roasts one after the other, wiping out the pan and adding new oil after searing the first roast. Both pieces of meat can be roasted on the same rack.

|

1 |

(2-pound) beef tenderloin center-cut Châteaubriand, trimmed |

|

2 |

teaspoons kosher salt |

|

1 |

teaspoon coarsely ground black pepper |

|

2 |

tablespoons unsalted butter, softened |

|

1 |

tablespoon vegetable oil |

|

1 |

recipe flavored butter (recipes follow) |

1. Using 12-inch lengths of twine, tie roast crosswise at 1½-inch intervals. Sprinkle roast evenly with salt, cover loosely with plastic wrap, and let stand at room temperature for 1 hour. Meanwhile, adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 300 degrees.

2. Pat roast dry with paper towels. Sprinkle roast evenly with pepper and spread butter evenly over surface. Transfer roast to wire rack set in rimmed baking sheet. Roast until center of roast registers 125 degrees (for medium-rare), 40 to 55 minutes, or 135 degrees (for medium), 55 to 70 minutes, flipping roast halfway through cooking.

3. Heat oil in 12-inch skillet over medium-high heat until just smoking. Place roast in skillet and sear until well browned on 4 sides, 4 to 8 minutes. Transfer roast to carving board and spread 2 tablespoons flavored butter evenly over top of roast; let rest for 15 minutes. Remove twine and cut meat crosswise into ½-inch-thick slices. Serve, passing remaining flavored butter separately.

SHALLOT AND PARSLEY BUTTER

MAKES ABOUT ½ CUP, ENOUGH FOR 1 RECIPE ROAST BEEF TENDERLOIN

|

4 |

tablespoons unsalted butter, softened |

|

½ |

shallot, minced |

|

1 |

garlic clove, minced |

|

1 |

tablespoon minced fresh parsley |

|

¼ |

teaspoon salt |

|

¼ |

teaspoon pepper |

Combine all ingredients in medium bowl.

BLUE CHEESE AND CHIVE BUTTER

MAKES ABOUT ½ CUP, ENOUGH FOR 1 RECIPE ROAST BEEF TENDERLOIN

|

1½ |

ounces (¼ cup) mild blue cheese, room temperature |

|

3 |

tablespoons unsalted butter, softened |

|

1⁄8 |

teaspoon salt |

|

2 |

tablespoons minced fresh chives |

Combine all ingredients in medium bowl.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Many recipes sear, then roast, beef tenderloin. But it takes a long time to sear a tenderloin straight from the refrigerator because a lot of surface moisture has to evaporate before any browning can occur. During this time, too much heat is transferred to the roast and you end up with a band of overcooked gray meat below the surface. Roasting the meat first ensures even cooking and evaporates surface moisture so that the searing time is just a few minutes.

BUY A CENTER-CUT ROAST A whole tenderloin is hard to handle. It’s usually covered with a lot of fat and sinew and the meat varies widely in girth. For indoor cooking, we much prefer to buy a center-cut tenderloin, also called a Châteaubriand, because it’s already trimmed and the thickness is the same from end to end. This 2-pound roast fits in a skillet and won’t break the bank either.

USE SALT AND BUTTER To add flavor to this relatively bland cut, we apply salt an hour before cooking. The salt pulls juices out of the meat, then reverses the flow, drawing flavor deep into the meat (see concept 12). For richness, we slather the roast with softened butter before cooking, then cover it with a compound butter as it rests.