CONCEPT 15

A Panade Keeps Ground Meat Tender

Let’s put the big, juicy, home-ground burgers aside. After all, it’s relatively easy to keep a rare burger tender and moist (see concept 14). It’s when ground beef is cooked through that the meat, no matter how lovingly handled, turns gray and you’re left with a dinner of dense, dry hockey pucks. But sometimes you need to fully cook beef: like the occasionally well-done burger (for kids, especially), not to mention in dishes like meatloaf or meatballs. So how do you cook ground beef until well-done? It’s amazing what a simple bread-and-milk paste can do to help.

HOW THE SCIENCE WORKS

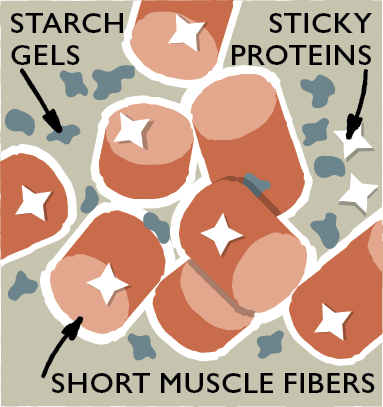

A panade is a mixture of starch and liquid. It can be simple (white bread and regular milk), or it can be complex (panko or saltines; buttermilk or yogurt or even added gelatin). But it always has the same set of goals: to keep ground meat moist and tender, and to help meatballs and meatloaf hold their shape. How does it work?

As we learned in concept 14, meat is made of long fibers of protein that run parallel to each other, producing bundled strands encased in sheaths of connective tissue. The length of individual muscle fibers can range from several to tens of centimeters. The collection of long fibers encased in tough connective tissue shrinks during cooking and therefore can be difficult to bite through. But when meat is ground and mixed, these proteins are cut into much smaller pieces. In the process, they exude a sticky mass of soluble proteins that glue the whole lot of it together in a tangled web. Upon cooking, this web of proteins can shrink as much as 25 percent, squeezing out excess moisture and, as a result, making burgers and meatballs that are dry and tough.

But all is not lost. That’s where the panade comes in. This mixture, most commonly of bread and milk, works in two ways. First, its liquid adds moisture to the ground meat. Second, the molecules of starch in the bread actually get in the way of the meat proteins, preventing them from interconnecting too strongly.

In addition, starches from the bread absorb liquid from the milk to form a gel that coats and lubricates the protein molecules in the meat, much in the same way as fat, keeping them moist and preventing them from linking together and shrinking into a tough matrix.

Starch from bread works in the same way as cornstarch when it is used to thicken a sauce or gravy. Starch granules absorb water and swell with heat, making the liquid thick and viscous. It takes little cornstarch to thicken a sauce, and so it also takes relatively little panade to keep ground meat from becoming tough and dry. Although plain water will work, milk adds more depth of flavor by contributing protein and lactose, a sugar, which combine to produce extra browning and flavor via the Maillard reaction.

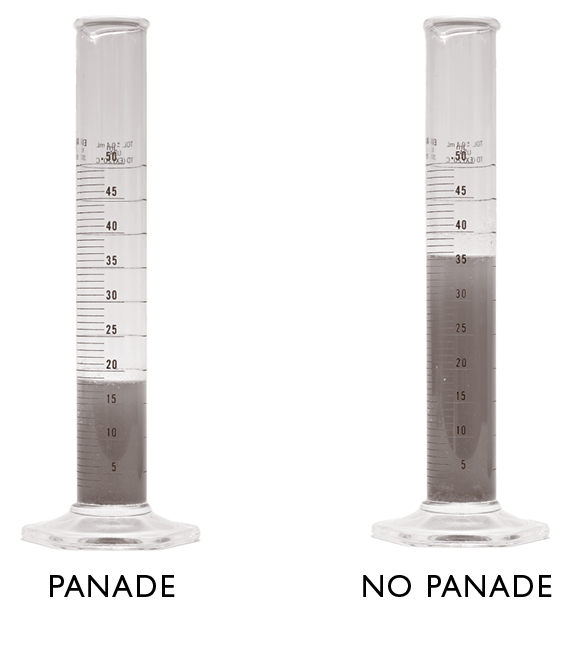

To test the effects of a panade in ground meat, we mixed up two batches of burger meat. One batch contained 12 ounces of 90 percent lean ground beef, half a slice of white bread, 1 tablespoon of milk, and ½ teaspoon of salt while the other had only the meat and salt. We made four 3-ounce (85-gram) patties from each batch and sealed each burger individually in an airtight bag. We then placed all of the burgers in a temperature-controlled hot water bath set to 160 degrees (the temperature of a well-done burger) and let them cook for 30 minutes (ample time for the burgers to reach 160 degrees throughout). After letting them cool for five minutes, we opened the bags and recorded the amount of liquid that had pooled around the burgers.

THE RESULTS

The burgers with the bread and milk panade lost 4.5 grams of liquid on average, or just over 5 percent of their weight. The patties made without panade shed twice that amount: 9 grams of liquid, or almost 11 percent of their weight.

THE TAKEAWAY

The goal when cooking ground meat is to minimize moisture loss, even when the meat is cooked to well-done. Without a panade, the meat proteins create a dense web that contracts when the meat is cooked. As a result, ground meat without a panade will expel a lot of moisture. The addition of a panade cuts this moisture loss in half. The mixture of starch and milk forms a gel-like substance that coats the meat proteins and prevents them from interconnecting too strongly. In addition, the milk adds more moisture to the equation so the end results are juicier and more tender.

PANADES AT WORK

BURGERS

Given the real food-safety issues surrounding ground beef from the supermarket, we recognize that many backyard cooks (and test cooks) grill their burgers to medium-well and beyond—especially when kids are around (the minimum temperature to kill all bacteria is 160 degrees). Instead of accepting the usual tough, desiccated hockey pucks with diminished beefy flavor, we use a simple panade (just a mixture of white bread and milk) to retain moisture and juiciness so our well-done burgers are truly done well.

WELL-DONE BURGERS

SERVES 4

Adding bread and milk to the beef creates burgers that are juicy and tender even when well-done. For cheeseburgers, follow the optional instructions below.

|

1 |

slice hearty white sandwich bread, crust removed, cut into ¼-inch pieces |

|

2 |

tablespoons whole milk |

|

2 |

teaspoons steak sauce |

|

1 |

garlic clove, minced |

|

¾ |

teaspoon salt |

|

¾ |

teaspoon pepper |

|

1½ |

pounds 80 percent lean ground chuck |

|

6 |

ounces sliced cheese (optional) |

|

4 |

hamburger rolls, toasted |

1. Mash bread and milk in large bowl with fork until homogeneous. Stir in steak sauce, garlic, salt, and pepper. Using hands, gently break up meat over bread mixture and toss lightly to distribute. Divide meat into 4 portions and lightly toss 1 portion from hand to hand to form ball, then lightly flatten ball with fingertips into ¾-inch-thick patty. Press center of patty down with fingertips until it is about ½ inch thick, creating slight depression. Repeat with remaining portions.

2A. FOR A CHARCOAL GRILL: Open bottom vent completely. Light large chimney starter filled with charcoal briquettes (6 quarts). When top coals are partially covered with ash, pour evenly over half of grill. Set cooking grate in place, cover, and open lid vent completely. Heat grill until hot, about 5 minutes.

2B. FOR A GAS GRILL: Turn all burners to high, cover, and heat grill until hot, about 15 minutes.

3. Clean and oil cooking grate. Place burgers on grill (on hot side if using charcoal) and cook, without pressing on them, until well browned on first side, 2 to 4 minutes. Flip burgers and cook for 3 to 4 minutes for medium-well or 4 to 5 minutes for well-done, adding cheese, if using, about 2 minutes before reaching desired doneness and covering grill to melt cheese.

4. Transfer burgers to serving platter, tent loosely with aluminum foil, and let rest for 5 to 10 minutes before serving on rolls.

WELL-DONE BACON-CHEESEBURGERS

Most bacon burgers simply top the burgers with bacon. We also add bacon fat to the ground beef, which adds juiciness and unmistakable bacon flavor throughout the burger.

Cook 8 slices bacon in skillet over medium heat until crisp, 7 to 9 minutes. Transfer bacon to paper towel–lined plate and set aside. Reserve 2 tablespoons fat and refrigerate until just warm. Add reserved bacon fat to beef mixture. Include optional cheese and top each burger with 2 slices bacon before serving.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

While developing a recipe for well-done hamburgers that would still be tender and moist, we opted to pack the patties with a very basic panade, a paste made from bread and milk that’s often used to keep meatloaf and meatballs moist.

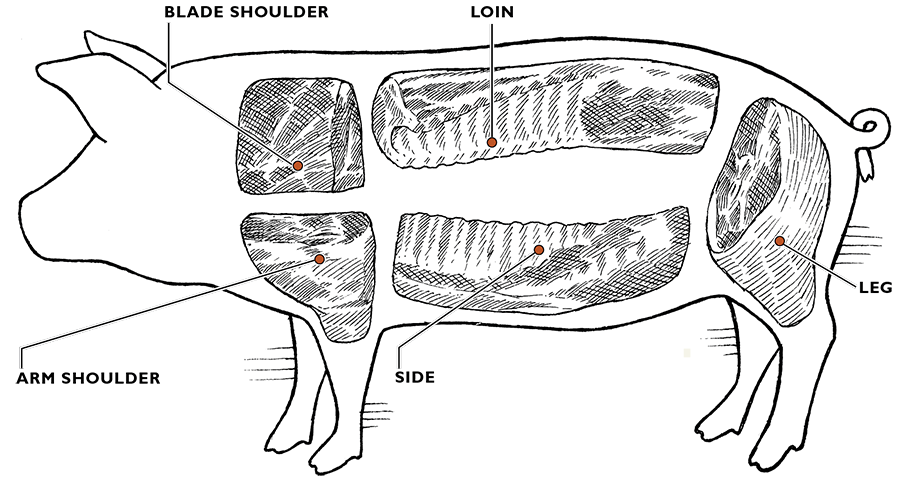

PICK YOUR GROUND CHUCK We work with supermarket ground beef here—nothing fancy. What type is best? Supermarkets sell beef according to the ratio of lean meat to fat, the three most common categories being 80 percent lean (usually from the chuck, or front shoulder), 85 percent (usually from the round, or hind legs), and 90 percent (usually from the sirloin). Our testers prefer the fattier 80 percent lean: The well-done chuck burgers are noticeably moister than the inedible versions we tried with the leaner sirloin.

SEASON AGGRESSIVELY To punch up the flavor in our well-done hamburger recipe, we add minced garlic and tangy steak sauce. This contributes to a deep, meaty flavor.

DON’T OVERWORK It’s important not to overwork these burger patties—too much handling can result in a rubbery burger. Aggressively grinding meat as they do in the supermarket, often multiple times, releases too many soluble proteins that act as a glue to stick the proteins together to form a dense, rubbery mass.

USE HIGH HEAT While cooking our burgers over a medium fire would ensure a juicier, more tender burger, it would be a burger without that flavorful sear. We cook these burgers over high heat to create great flavor. The panade helps to stem the moisture loss along the way.

PANADES AT WORK

MEATLOAF, MEAT SAUCE, MEATBALLS

When making loaves, sauces, and balls with ground meat, our panades are often tweaked from the traditional white bread and milk combination. This can range from using saltines or panko as the bread, and yogurt or buttermilk instead of milk. In a clever twist, we’ve found that adding baking powder as part of the panade can leaven meat just as it does bread, creating delicate and juicy Swedish meatballs.

GLAZED ALL-BEEF MEATLOAF

SERVES 6 TO 8

We suggest you use 1 pound of ground chuck and 1 pound of ground sirloin for the ground beef, though you may substitute any 85 percent lean ground beef. Handle the meat gently; it should be thoroughly combined but not pastelike. To avoid using the broiler, glaze the loaf in a 500-degree oven; increase the cooking time for each interval by two to three minutes.

|

MEATLOAF |

|

|

3 |

ounces Monterey Jack cheese, shredded (¾ cup) |

|

1 |

tablespoon unsalted butter |

|

1 |

onion, chopped fine |

|

1 |

celery rib, chopped fine |

|

2 |

teaspoons minced fresh thyme |

|

1 |

garlic clove, minced |

|

1 |

teaspoon paprika |

|

¼ |

cup tomato juice |

|

½ |

cup low-sodium chicken broth |

|

2 |

large eggs |

|

½ |

teaspoon unflavored gelatin |

|

2⁄3 |

cup crushed saltines (about 16) |

|

2 |

tablespoons minced fresh parsley |

|

1 |

tablespoon soy sauce |

|

1 |

teaspoon Dijon mustard |

|

¾ |

teaspoon salt |

|

½ |

teaspoon pepper |

|

2 |

pounds 85 percent lean ground beef |

|

GLAZE |

|

|

½ |

cup ketchup |

|

¼ |

cup cider vinegar |

|

3 |

tablespoons packed light brown sugar |

|

1 |

teaspoon hot sauce |

|

½ |

teaspoon ground coriander |

1. FOR THE MEATLOAF: Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 375 degrees. Spread cheese on plate and place in freezer until ready to use. Fold piece of heavy-duty aluminum foil to form 10 by 6-inch rectangle. Center foil on wire rack and place rack in rimmed baking sheet. Poke holes in foil with skewer about ½ inch apart. Spray foil with vegetable oil spray and set aside.

2. Melt butter in 10-inch skillet over medium-high heat; add onion and celery and cook, stirring occasionally, until beginning to brown, 6 to 8 minutes. Add thyme, garlic, and paprika and cook, stirring constantly, until fragrant, about 1 minute. Reduce heat to low and add tomato juice. Cook, scraping bottom of skillet with wooden spoon to loosen any browned bits, until thickened, about 1 minute. Transfer mixture to bowl and set aside to cool.

3. Whisk broth and eggs in large bowl until combined. Sprinkle gelatin over liquid and let stand for 5 minutes. Stir in saltines, parsley, soy sauce, mustard, salt, pepper, and onion mixture. Crumble frozen cheese into coarse powder and sprinkle over mixture. Add ground beef; mix gently with hands until thoroughly combined, about 1 minute. Transfer meat to foil rectangle and shape into 10 by 6-inch oval about 2 inches high. Smooth top and edges of meatloaf with moistened spatula. Bake until meatloaf registers 135 to 140 degrees, 55 to 65 minutes. Remove meatloaf from oven and turn on broiler.

4. FOR THE GLAZE: While meatloaf cooks, combine glaze ingredients in small saucepan; bring to simmer over medium heat and cook, stirring, until thick and syrupy, about 5 minutes. Spread half of glaze evenly over cooked meatloaf with rubber spatula; place under broiler and cook until glaze bubbles and begins to brown at edges, about 5 minutes. Remove meatloaf from oven and spread evenly with remaining glaze; place back under broiler and cook until glaze is again bubbling and beginning to brown, about 5 minutes more. Cool meatloaf for about 20 minutes before slicing.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

For a tender, moist, and light meatloaf, a combination of ground beef, pork, and veal (known as meatloaf mix) is usually the way to go. But sometimes we can’t find meatloaf mix or don’t have it on hand. For an all-beef loaf that’s just as good as one made with meatloaf mix, we recommend using equal parts ground chuck and sirloin, which provide just the right balance of juicy, tender meat and assertive beefy flavor. (Simply using 85 percent lean ground beef works, too.) A panade along with frozen, grated cheese adds moisture as well as fat.

ADD A PANADE We use saltines as the bread for our panade, delivering a well-seasoned, tender loaf with good moisture. Instead of milk, which does little to tone down beef’s naturally liver-y flavor, we use chicken broth, which adds savory notes to the loaf. Powdered gelatin rounds out the panade, replacing what was lost in the ground veal of a meatloaf mix, and giving our version a luxurious smoothness.

USE FROZEN CHEESE We add cheese to this meatloaf for its flavor, moisture, and binding quality. We don’t want little pockets of cheese that ooze unappealing liquid when the loaf is cut, though. Therefore, the method to break down the cheese for this recipe is critical. Dicing and shredding leaves those undesirable hot pockets of cheese. Grated cheese proves superior, and freezing the grated cheese keeps it crumbly.

BIND WITH EGGS While the additions of frozen, grated cheese and a panade made of saltines, chicken broth, and gelatin are important steps toward binding the meatloaf together, more is required. We also add 2 large eggs to the mix. The eggs, which solidify as they cook, hold in moisture and add body to the meatloaf.

BAKE FREE-FORM Allowing meatloaf baked in a loaf pan to stew in its own juices makes for a greasy mess. We ditch the loaf pan and bake the meatloaf “free-form” on a raised rectangle we make from aluminum foil set atop a wire cooling rack. Setting the meatloaf on this raised surface not only allows the fat to drain away, preventing the meatloaf from tasting greasy, it also encourages allover browning, which adds a layer of flavor. (Because the bigger surface area and browning invite moisture loss, we add a panade.)

GLAZE LATE The almost-finished meatloaf needs its crowning glory—a glaze. But applied at the beginning of cooking, the glaze mixes unappealingly with the liquids seeping out of the loaf. Finishing with the glaze produces better results, especially when placing the loaf briefly under the broiler.

SIMPLE ITALIAN-STYLE MEAT SAUCE

SERVES 8 TO 10

High-quality canned tomatoes will make a big difference in this sauce. We recommend Hunt’s and Muir Glen diced tomatoes, and Tuttorosso and Muir Glen crushed tomatoes. If using dried oregano, add the entire amount with the canned tomato liquid in step 2.

|

4 |

ounces white mushrooms, trimmed and halved if small or quartered if large |

|

1 |

slice hearty white sandwich bread, torn into quarters |

|

2 |

tablespoons whole milk |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

1 |

pound 85 percent lean ground beef |

|

1 |

tablespoon olive oil |

|

1 |

large onion, chopped fine |

|

6 |

garlic cloves, minced |

|

1 |

tablespoon tomato paste |

|

¼ |

teaspoon red pepper flakes |

|

1 |

(14.5-ounce) can diced tomatoes, drained with ¼ cup juice reserved |

|

1 |

tablespoon minced fresh oregano or 1 teaspoon dried |

|

1 |

(28-ounce) can crushed tomatoes |

|

¼ |

cup grated Parmesan cheese, plus extra forserving |

|

2 |

pounds spaghetti or linguine |

1. Pulse mushrooms in food processor until finely chopped, about 8 pulses, scraping down sides as needed; transfer to bowl. Add bread, milk, ½ teaspoon salt, and ½ teaspoon pepper to now-empty food processor and pulse until paste forms, about 8 pulses. Add ground beef and pulse until mixture is well combined, about 6 pulses.

2. Heat oil in large saucepan over medium-high heat until just smoking. Add onion and mushrooms and cook until vegetables are softened and well browned, 6 to 12 minutes. Stir in garlic, tomato paste, and pepper flakes and cook until fragrant and tomato paste starts to brown, about 1 minute. Stir in reserved tomato juice and 2 teaspoons oregano, scraping up any browned bits. Stir in meat mixture and cook, breaking up any large pieces with wooden spoon, until no longer pink, about 3 minutes, making sure that meat does not brown.

3. Stir in diced tomatoes and crushed tomatoes, bring to gentle simmer, and cook until sauce has thickened and flavors meld, about 30 minutes. Stir in Parmesan and remaining 1 teaspoon oregano and season with salt and pepper to taste. (Sauce can be refrigerated for up to 2 days or frozen for up to 1 month.)

4. Meanwhile, bring 8 quarts water to boil in 12-quart pot. Add pasta and 2 tablespoons salt and cook, stirring often, until al dente. Reserve ½ cup cooking water, then drain pasta and return it to pot. Add 1 cup sauce and reserved cooking water to pasta and toss to combine. Serve, topping individual portions with more sauce and passing Parmesan separately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Simmering a meat sauce all day does two things: It concentrates flavors as the liquid reduces slowly over the three- to four-hour cooking time; and it breaks down the meat, giving it a soft, lush texture. For a quick meat sauce that tastes as if it had simmered all day, we use a few tricks: Instead of browning the meat, we brown mushrooms to give the sauce flavor without drying it out. We blend a panade into the meat before cooking, to keep it tender. Finally, for good tomato flavor, we add tomato paste to the browned vegetables in our meat sauce recipe and deglaze the pan with a little tomato juice before adding canned tomatoes.

TEACH AN OLD PANADE NEW TRICKS We use a basic panade in this sauce (white bread, whole milk). Even though it’s for a sauce and not a compact construction like a burger, meatball, or meatloaf, the goal is the same: producing tender, juicy meat. Here, we mix the beef and panade in a food processor in order to help ensure that the starch is well dispersed so that all the meat reaps its benefits. The food processor also breaks the meat into tiny pieces that cook up supple and tender. When we skipped this step, the meat was chunkier—more like chili than a good sauce.

USE FLAVOR ENHANCERS We ramp up flavor in this quick sauce in a few ways. First: mushrooms. Basic white ones (browned in the pan with an onion) are enough to impart a real beefy taste. We also add tomato paste and Parmesan cheese, which are rich in glutamates (see concept 35) and add an umami, or savory, taste, along with liberal amounts of red pepper flakes and fresh oregano.

GRIND THE MUSHROOMS, TOO We process the mushrooms in a food processor until finely chopped before browning them in a pan. After all, we want the beefy flavor that the mushrooms add to the sauce but are not interested in their squishy texture. This way, the mushrooms blend right in with the ground beef.

DEGLAZE WITH JUICE We save some tomato juice from the drained diced tomatoes to deglaze the pan after browning the mushrooms. This (plus a bit of tomato paste) gives the sauce’s tomato flavor a boost.

CLASSIC SPAGHETTI AND MEATBALLS FOR A CROWD

SERVES 12

If you don’t have buttermilk, you can substitute 1 cup of plain yogurt thinned with ½ cup of milk. Grate the onion on the large holes of a box grater. You can cook the pasta in two separate pots if you do not have a pot large enough to cook all of the pasta together. The ingredients in this recipe can be reduced by two-thirds to serve four.

|

MEATBALLS |

|

|

2¼ |

cups panko bread crumbs |

|

1½ |

cups buttermilk |

|

1½ |

teaspoons unflavored gelatin |

|

3 |

tablespoons water |

|

2 |

pounds 85 percent lean ground beef |

|

1 |

pound ground pork |

|

6 |

ounces thinly sliced prosciutto, chopped fine |

|

3 |

large eggs |

|

3 |

ounces Parmesan cheese, grated (1½ cups) |

|

6 |

tablespoons minced fresh parsley |

|

3 |

garlic cloves, minced |

|

1½ |

teaspoons salt |

|

½ |

teaspoon pepper |

|

SAUCE |

|

|

3 |

tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil |

|

1 |

large onion, grated |

|

6 |

garlic cloves, minced |

|

1 |

teaspoon dried oregano |

|

½ |

teaspoon red pepper flakes |

|

3 |

(28-ounce) cans crushed tomatoes |

|

6 |

cups tomato juice |

|

6 |

tablespoons dry white wine |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

½ |

cup minced fresh basil |

|

3 |

tablespoons minced fresh parsley |

|

|

Sugar |

|

3 |

pounds spaghetti |

|

2 |

tablespoons salt |

|

|

Grated Parmesan cheese |

1. FOR THE MEATBALLS: Adjust oven racks to lower-middle and upper-middle positions and heat oven to 450 degrees. Line 2 rimmed baking sheets with aluminum foil, set wire racks in baking sheets, and spray racks with vegetable oil spray.

2. Combine bread crumbs and buttermilk in large bowl and let sit, mashing occasionally with fork, until smooth paste forms, about 10 minutes. Meanwhile, sprinkle gelatin over water in small bowl and allow to soften for 5 minutes.

3. Mix ground beef, ground pork, prosciutto, eggs, Parmesan, parsley, garlic, salt, pepper, and gelatin mixture into bread-crumb mixture using hands. Pinch off and roll mixture into 2-inch meatballs (about 40 meatballs total) and arrange on prepared racks. Bake until well browned, about 30 minutes, switching and rotating baking sheets halfway through baking.

4. FOR THE SAUCE: While meatballs bake, heat oil in Dutch oven over medium heat until shimmering. Add onion and cook until softened and lightly browned, 5 to 7 minutes. Stir in garlic, oregano, and pepper flakes and cook until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Stir in crushed tomatoes, tomato juice, wine, 1½ teaspoons salt, and ¼ teaspoon pepper, bring to simmer, and cook until thickened slightly, about 15 minutes.

5. Remove meatballs from oven and reduce oven temperature to 300 degrees. Gently nestle meatballs into sauce. Cover, transfer to oven, and cook until meatballs are firm and sauce has thickened, about 1 hour. (Sauce and meatballs can be cooled and refrigerated for up to 2 days. To reheat, drizzle ½ cup water over sauce, without stirring, and reheat on lower-middle rack of 325-degree oven for 1 hour.)

6. Meanwhile, bring 10 quarts water to boil in 12-quart pot. Add pasta and salt and cook, stirring often, until al dente. Reserve ½ cup cooking water, then drain pasta and return it to pot.

7. Gently stir basil and parsley into sauce and season with sugar, salt, and pepper to taste. Add 2 cups sauce (without meatballs) to pasta and toss to combine. Add reserved cooking water as needed to adjust consistency. Serve, topping individual portions with more tomato sauce and several meatballs and passing Parmesan separately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Making spaghetti and meatballs to serve a crowd can try the patience of even the toughest Italian grandmother. We sought an easier way and found that roasting our meatballs on a wire rack, rather than frying them in batches, makes our recipe faster and cleaner. Adding some powdered gelatin to a mix of ground chuck and ground pork serves to plump the meatballs and lends them a soft richness.

USE A MEAT COMBO Though we tried making these meatballs with beef alone—using 85 percent lean ground beef (anything less fatty would almost certainly produce a dry, bland meatball)—we found that replacing some of the beef with ground pork (we like a 2:1 ratio best) makes for a markedly richer, meatier taste.

PICK PANKO For this panade we use panko, super-crunchy Japanese bread crumbs that hold on to meat juices and keep the meatballs from getting tough, along with buttermilk, which adds more flavor to meatballs than regular milk. One cup of plain yogurt thinned with half a cup of milk can be substituted for the buttermilk.

GRATE THE ONION TO REDUCE CRUNCH We grate the onion for this sauce on the large holes of a box grater. This allows us to have the onion taste without the big crunch. We don’t even have to sauté it first.

BUILD FLAVOR We chop up some prosciutto, which is packed with glutamates (see concept 35) that enhance savory flavor, and mix it in with the meat for an extra-meaty flavor. Parmesan, too, adds lots of glutamates.

ADD GELATIN We pondered adding veal to these meatballs because veal has lots of gelatin and could add suppleness to the dish. While the veal did add suppleness, another problem arose, though: Ultra-lean veal is usually ground very fine, and these meatballs lacked the pleasantly coarse texture of the beef-and-pork batch. Instead, we add 1½ teaspoons of powdered gelatin moistened in a little water to the meatballs. Works like a charm.

FLAVOR THE SAUCE Because we roast our meatballs in the oven, there are no pan drippings to add flavor to the sauce. This is why we drop the roasted meatballs into the simple marinara sauce and braise them together in the oven for an hour. With time, the rich flavor of the browned meat infiltrates the sauce. One problem we found with this technique, however, was that as the meatballs absorb the liquid around them, the sauce can overreduce in the oven. To combat this, we swap almost half of the crushed tomatoes in our marinara recipe for an equal portion of tomato juice, leaving us with a full-bodied, but not sludgy, sauce.

SWEDISH MEATBALLS

SERVES 4 TO 6

The traditional accompaniments for Swedish meatballs are lingonberry preserves and Swedish Pickled Cucumbers (recipe follows). If you can’t find lingonberry preserves, cranberry preserves may be used. For a slightly less sweet dish, omit the brown sugar in the meatballs and reduce the brown sugar in the sauce to 2 teaspoons. A 12-inch slope-sided skillet can be used in place of the sauté pan—use 1½ cups of oil for frying instead of 1¼ cups. Serve the meatballs with mashed potatoes, boiled red potatoes, or egg noodles.

|

MEATBALLS |

|

|

1 |

large egg |

|

¼ |

cup heavy cream |

|

1 |

slice hearty white sandwich bread, crusts removed, torn into 1-inch pieces |

|

8 |

ounces ground pork |

|

¼ |

cup grated onion |

|

1½ |

teaspoons salt |

|

1 |

teaspoon packed brown sugar |

|

1 |

teaspoon baking powder |

|

1⁄8 |

teaspoon ground nutmeg |

|

1⁄8 |

teaspoon ground allspice |

|

1⁄8 |

teaspoon pepper |

|

8 |

ounces 85 percent lean ground beef |

|

1¼ |

cups vegetable oil |

|

SAUCE |

|

|

1 |

tablespoon unsalted butter |

|

1 |

tablespoon all-purpose flour |

|

1½ |

cups low-sodium chicken broth |

|

1 |

tablespoon packed brown sugar |

|

½ |

cup heavy cream |

|

2 |

teaspoons lemon juice |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

1. FOR MEATBALLS: Whisk egg and cream together in bowl. Stir in bread and set aside. Meanwhile, using stand mixer fitted with paddle, beat pork, onion, salt, sugar, baking powder, nutmeg, allspice, and pepper on high speed until smooth and pale, about 2 minutes, scraping down bowl as necessary. Using fork, mash bread mixture until no large dry bread chunks remain; add mixture to mixer bowl and beat on high speed until smooth and homogeneous, about 1 minute, scraping bowl as necessary. Add beef and mix on medium-low speed until just incorporated, about 30 seconds, scraping down bowl as necessary. Using moistened hands, form generous tablespoon of meat mixture into 1-inch round meatball; repeat with remaining mixture to form 25 to 30 meatballs.

2. Heat oil in 10-inch straight-sided sauté pan over medium-high heat until edge of meatball dipped in oil sizzles (oil should register 350 degrees on instant-read thermometer), 3 to 5 minutes. Add meatballs in single layer and fry, flipping once halfway through cooking, until lightly browned all over and cooked through, 7 to 10 minutes. (Adjust heat as needed to keep oil sizzling but not smoking.) Using slotted spoon, transfer browned meatballs to paper towel–lined plate.

3. FOR SAUCE: Pour off and discard oil in pan, leaving any browned bits behind. Return pan to medium-high heat and melt butter. Add flour and cook, whisking constantly, until flour is light brown, about 30 seconds. Slowly whisk in broth, scraping bottom of pan with wooden spoon to loosen any browned bits. Add sugar and bring to simmer. Reduce heat to medium and cook until sauce is reduced to about 1 cup, about 5 minutes. Stir in cream and return to simmer.

4. Add meatballs to sauce and simmer, turning occasionally, until heated through, about 5 minutes. Stir in lemon juice, season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve.

TO MAKE AHEAD: Meatballs can be fried and then frozen for up to 2 weeks. To continue with recipe, thaw meatballs in refrigerator overnight and proceed from step 3, using clean pan.

SWEDISH PICKLED CUCUMBERS

MAKES 3 CUPS, ENOUGH FOR 1 RECIPE SWEDISH MEATBALLS

Kirby cucumbers are also called pickling cucumbers. If these small cucumbers are unavailable, substitute 1 large American cucumber. Serve the pickles chilled or at room temperature.

|

3 |

small Kirby cucumbers (1 pound), sliced into 1⁄8- to ¼-inch-thick rounds |

|

1½ |

cups distilled white vinegar |

|

1½ |

cups sugar |

|

1 |

teaspoon salt |

|

12 |

whole allspice berries |

Place cucumber slices in medium heatproof bowl. Bring vinegar, sugar, salt, and allspice to simmer in small saucepan over high heat, stirring occasionally to dissolve sugar. Pour vinegar mixture over cucumbers and stir to separate slices. Cover bowl with plastic wrap and let sit for 15 minutes. Uncover and cool to room temperature, about 15 minutes.

TO MAKE AHEAD: Pickles can be refrigerated in their liquid in airtight container for up to 2 weeks.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Most of us know Swedish meatballs as lumps of flavorless ground beef or pork covered in heavy gravy that congeals as it sits. But when done right these main-course meatballs are melt-in-your-mouth tender, substantial yet delicate. To achieve the right texture, we combine beef, pork, a panade (a mixture of bread, egg, and cream), and a surprise ingredient, baking powder, which keeps the meatballs delicate and juicy.

STRIVE FOR SPRINGY While Italian meatballs are ideally moist and almost fall-apart tender, that’s not at all what we want in Swedish meatballs. We want them to be springy. Therefore, we still use both pork and beef, but we use cream (rather than milk) and egg along with bread for a small amount of panade. The extra fat from the cream and egg coats the starch granules, reducing the extent of hydration and swelling so the structure is springy rather than loose. The egg protein also adds both structure and springiness.

LIGHTEN WITH BAKING POWDER We don’t end our textural quest there, though. With the mixture of pork and beef, as well as our creamy panade, our meatballs still turned out a bit dry and dense. We wanted to lighten them up. Thinking of other ingredients used elsewhere to do just that, we turned to baking powder. Can it leaven a meatball the way it leavens bread? Indeed. We use a single teaspoon of baking powder to help produce meatballs with the ideal moistness, substance, and lightness.

GRATE ONIONS Just as we do in our recipe for Classic Spaghetti and Meatballs for a Crowd, we grate the onion on a box grater here. This way we have the taste of onion without its crunch.

MIX THE PORK, NOT THE BEEF We add a bit of sausagelike springiness by whipping the pork in a stand mixer along with the salt, baking powder, and seasonings until an emulsified paste forms before adding the panade and the ground beef. We whip the pork and not the beef because the pork has a higher fat content and less robust muscle structure. Whipping it finely distributes the fat into the lean meat, thus guaranteeing a juicy finished product.

USE FOND FOR FLAVOR For the gravy, we wanted a light cream sauce instead of a heavy brown one. To get this, we add a bit of cream to our stock to lighten it up and a splash of lemon juice for bright flavor. We make it in the same pan that we use for the meatballs, scraping up the browned bits, or fond, for extra flavor.

PICKLE QUICKLY Swedish pickled cucumbers are a traditional accompaniment to these meatballs. Here, we heat the vinegar with the sugar, salt, and allspice before pouring it over the cucumbers. The warm vinegar (a mild acid) with dissolved salt and sugar not only adds seasoning but quickly draws moisture out of the cucumbers, creating a texture that is more like a pickle than a crisp cucumber.