CONCEPT 26

Potato Starches Can Be Controlled

Potatoes contain a great deal of starch. Sometimes these starches work against us, causing gluey mashed potatoes. Other times the surplus starch is exactly what we need for crisp, browned home fries. We don’t leave our results up to chance, however. Taking control of the starches in potatoes is easy: Use simple steps to either remove or activate starch, depending on the dish.

HOW THE SCIENCE WORKS

We learned in concept 25 that anywhere between 16 and 22 percent of a raw potato’s weight is made up of starch. We also learned that there are two types of starch molecules: amylose and amylopectin, which act in different ways. Because each variety of potato has different amounts of starch and moisture, this means that some potatoes are best for mashing (the fluffy varieties such as russet) and others for boiling and retaining their shape (the less dense, waxy Red Bliss). In addition to choosing the best potato for the job, there are things that we can do to help control the starches in potatoes, enhancing or eliminating them with different techniques as we cook.

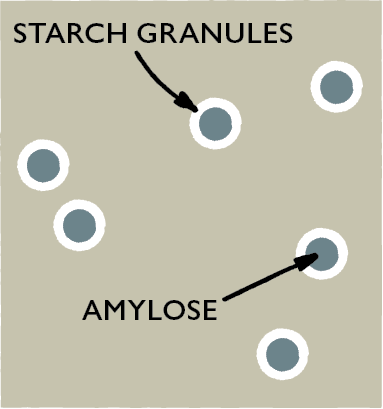

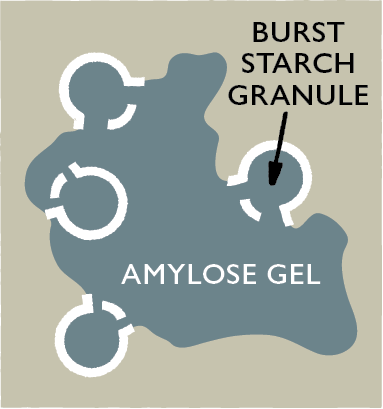

When we cook potatoes, the starch granules within the potato cells are greatly affected. These granules begin to absorb water when the temperature of the potato hits 140 degrees. They swell intensely by 160 degrees. The danger here is that the starch granules can rupture if they get too hot and absorb too much water. And when they burst, they spill out a sticky gel made of amylose. If the potato cells holding these burst starch granules also explode, this released amylose will no doubt turn potatoes into a gluey mess. This becomes a significant problem when the temperature reaches 180 degrees. At this point, pectin, which acts as a glue surrounding the cells and within the cell walls, begins to break down, becomes water-soluble, and dissolves, causing the cells to separate and the cell walls to break open, releasing the gel. Overcooked potatoes, because a large percentage of their starch granules have exploded, produce a great deal of sticky gel, making them extremely gluey, even if they are easy to mash. (These starch granules can also explode if the potatoes are overworked after cooking.)

To prevent a gluey dish, we often remove starch by rinsing it off of the cut potatoes either before, during, or after cooking. Rinsing helps remove some of the free starch that has escaped from the potato’s starch granules. With less starch, the potatoes are less inclined to become gluey and thick when cooked, and we’re left with mashed potatoes, for example, with a lighter, silkier texture.

Sometimes, however, we want to use this excess starch to our advantage. We can do this by activating the starch granules—in a controlled setting. This can be as simple as stirring or using the food processor. We use techniques like this to manipulate texture for dishes that are meant to have a more sticky, tacky texture (like some kinds of mashed potatoes), or to promote browning by activating extra starch on the surface of a slice of potato going in to roast (the starch will convert to sugar and form a nicely browned crust).

To demonstrate that how you handle a potato once it is cooked can be just as important as which potato variety you choose, we mashed batches of potatoes in two different ways. First, we made a batch of mashed potatoes by gently folding warm milk and butter into a bowl of russets that we had processed with a ricer. For the other batch, we used the fast action of a food processor blade to puree the ingredients into the potatoes for 30 seconds. We repeated the test three times.

THE RESULTS

While the folded batch of mashed potatoes was fluffy, the sample out of the food processor was sticky, a sign of burst starch granules. Tasters unanimously preferred the folded potatoes, which were described as “light.” Tasters found the potatoes made in the food processor to be “too thick” and “gluey.”

THE TAKEAWAY

Because potatoes have so much starch, which can drastically alter the texture of the finished dish, it’s important to handle them with care.

As our experiment shows, the texture of potatoes run through a food processor is sticky and gummy—and, unless we’re making Aligot, this is everything we don’t want in a classic mashed potato dish. Why is the texture so different? Because a food processor, with its sharp blade, is a full-contact tool, using one is an especially rough method of creaming a vegetable. It slices through many—if not all—of the already-expanded starch granules and cells in the potatoes, causing them to burst and release the sticky amylose strands. This creates a gel that turns the potato dish into a substance closer to glue than mashed potatoes.

The potatoes we barely touched, however, kept their starch granules and cells intact. Without the rough handling, the starch granules were not punctured or split, and a good deal of the amylose remained within the intact cells, allowing us to finish with a light and fluffy mashed potato.

In conclusion: The method of handling your potatoes will affect the texture of your final dish. Pay careful attention to how much—or how little—you process your spuds. It could mean the difference between a puddle of glue and a dish so fluffy it resembles a cloud.

RINSING AWAY STARCHES AT WORK

MASHED POTATOES AND ROESTI

To control the levels of sticky starch glue released from potatoes in such recipes as Mashed Potatoes and Root Vegetables (next) and Potato Roesti, we rinse it away. This helps prevent the finished dishes from becoming heavy and dense.

MASHED POTATOES AND ROOT VEGETABLES

SERVES 4

Russet potatoes will yield a slightly fluffier, less creamy mash, but they can be used in place of the Yukon Gold potatoes if desired. Rinsing the potatoes in water reduces starch and helps prevent the mashed potatoes from becoming gluey. It is important to cut the potatoes and root vegetables into evenly sized pieces so they cook at the same rate. This recipe can be doubled and cooked in a large Dutch oven. If doubling, increase the cooking time in step 2 to 40 minutes.

|

4 |

tablespoons unsalted butter |

|

8 |

ounces carrots, parsnips, turnips, or celery root, peeled, carrots or parsnips cut into ¼-inch-thick half-moons, turnips or celery root cut into ½-inch dice (about 1½ cups) |

|

1½ |

pounds Yukon Gold potatoes, peeled, quartered lengthwise, and cut crosswise into ¼-inch-thick slices, rinsed and well drained |

|

1⁄3 |

cup low-sodium chicken broth |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

¾ |

cup half-and-half, warmed |

|

3 |

tablespoons minced fresh chives |

1. Melt butter in large saucepan over medium heat. Add root vegetables and cook, stirring occasionally, until butter is browned and vegetables are dark brown and caramelized, 10 to 12 minutes. (If after 4 minutes vegetables have not started to brown, increase heat to medium-high.)

2. Add potatoes, broth, and ¾ teaspoon salt and stir to combine. Cook, covered, over low heat (broth should simmer gently; do not boil), stirring occasionally, until potatoes fall apart easily when poked with fork and all liquid has been absorbed, 25 to 30 minutes. (If liquid does not gently simmer after a few minutes, increase heat to medium-low.) Remove pan from heat, remove lid, and allow steam to escape for 2 minutes.

3. Gently mash potatoes and root vegetables in saucepan with potato masher (do not mash vigorously). Gently fold in warm half-and-half and chives. Season with salt and pepper to taste; serve immediately.

MASHED POTATOES AND ROOT VEGETABLES WITH BACON AND THYME

Cook 4 slices bacon, cut into ½-inch pieces, in large saucepan over medium heat until crisp, 5 to 7 minutes. Using slotted spoon, transfer bacon to paper towel–lined plate; set aside. Pour off all but 2 tablespoons fat from pan. Add 2 tablespoons butter to pan and continue with step 1, cooking root vegetables in bacon fat mixture instead of butter. Substitute 1 teaspoon minced fresh thyme for chives and fold reserved bacon into potatoes along with thyme.

MASHED POTATOES AND ROOT VEGETABLES WITH PAPRIKA AND PARSLEY

This variation is particularly nice with carrots.

Toast 1½ teaspoons smoked or sweet paprika in 8-inch skillet over medium heat until fragrant, about 30 seconds. Substitute parsley for chives and fold toasted paprika into potatoes along with parsley.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Root vegetables like carrots, parsnips, turnips, and celery root can add an earthy, intriguing flavor to mashed potatoes, but despite being neighbors in the root cellar, root vegetables contain more water (80 percent to 92 percent) than russet potatoes (about 79 percent), the test kitchen’s first choice for mashing. Root vegetables also have less starch (between 0.2 percent and 6.2 percent wet weight) than potatoes (about 16 to 22 percent). Finally, many root vegetables are either noticeably sweet or slightly bitter—traits that can overwhelm mild potatoes. So knowing that treating root vegetables and potatoes the same way can create a bad dish, adding up to a watery, lean, or saccharine mash, we played with the ratio, caramelized the root vegetables, and braised them all in chicken broth. But to avoid a gluey texture we hit the sink.

USE THE RIGHT RATIO You need to use far fewer root vegetables than you think for this recipe. The usual 1:1 ratio of root vegetables to potatoes in other recipes proves to be too thin because of the extra moisture in the root vegetables. We found that a 1:3 ratio is much better.

BROWN, BABY, BROWN Because we use fewer root vegetables, however, it’s imperative to enhance their flavor. Browning them in butter (not oil) does the job.

MAKE IT A ONE-POT WONDER With the vegetables being browned in one pot, why dirty a second pot just to boil the potatoes? We add the raw potatoes to the pot with the browned root vegetables and braise them. We prefer chicken stock to water as the liquid for extra flavor. Once they are tender, we mash the root veggies and potatoes right in the butter.

RINSE AWAY STARCH When boiling peeled chunks of russets, you wash away the excess starch as part of the cooking process. Braising, however, means the finished dish will contain all that starch. Switching to Yukon Golds helps, but to further cut down on starch you need to rinse the sliced potatoes before adding them to the pot. (Rinsing will even make russets an acceptable—if slightly less fluffy—choice.)

USE HALF-AND-HALF After cooking the root vegetables, the butter is already in the pot, so we just need to add the dairy. As usual, we prefer half-and-half.

POTATO ROESTI

SERVES 4

The test kitchen prefers a roesti prepared with potatoes that have been cut with the large shredding disk of a food processor. It is possible to use a box grater to cut the potatoes, but they should be cut lengthwise, so you are left with long shreds. It is imperative to squeeze the potatoes as dry as possible. A well-seasoned cast-iron skillet can be used in place of the nonstick skillet. With the addition of fried eggs, bacon, or cheese, roesti can be turned into a light meal for two.

|

1½ |

pounds Yukon Gold potatoes, peeled and shredded |

|

1 |

teaspoon cornstarch |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

4 |

tablespoons unsalted butter |

1. Place potatoes in large bowl and fill with cold water. Using hands, swirl to remove excess starch, then drain.

2. Wipe bowl dry. Place half of potatoes in center of kitchen towel. Gather ends together and twist as tightly as possible to expel maximum moisture. Transfer potatoes to bowl and repeat process with remaining potatoes.

3. Sprinkle cornstarch, ½ teaspoon salt, and pepper to taste over potatoes. Using hands or fork, toss ingredients together until well blended.

4. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in 10-inch nonstick skillet over medium heat. Add potato mixture and spread into even layer. Cover and cook for 6 minutes. Remove cover and, using spatula, gently press potatoes down to form round cake. Cook, occasionally pressing on potatoes to shape into uniform round cake, until bottom is deep golden brown, 4 to 6 minutes longer.

5. Shake skillet to loosen roesti and slide onto large plate. Add remaining 2 tablespoons butter to skillet and swirl to coat pan. Invert roesti onto second plate and slide it, browned side up, back into skillet. Cook, occasionally pressing down on cake, until bottom is well browned, 7 to 9 minutes. Remove pan from heat and allow cake to cool in pan for 5 minutes. Transfer roesti to cutting board, cut into 4 pieces, and serve immediately.

POTATO ROESTI WITH FRIED EGGS AND PARMESAN

SERVES 2 AS A MAIN COURSE

Slide 2 fried eggs onto finished roesti, sprinkle with ½ cup grated Parmesan cheese, and season with salt to taste.

POTATO ROESTI WITH BACON, ONION, AND SHERRY VINEGAR

SERVES 2 AS A MAIN COURSE

Cook 3 chopped slices bacon in 10-inch skillet over medium-high heat until crisp, 5 to 7 minutes. Transfer bacon to paper towel–lined plate and pour off all but 1 tablespoon fat from skillet. Add 1 thinly sliced large onion to skillet, season with salt and pepper, and cook until onion is softened, about 5 to 7 minutes, topping finished roesti with bacon and onion and sprinkling with sherry vinegar to taste before serving.

CHEESY POTATO ROESTI

SERVES 2 AS A MAIN COURSE

While not traditional, sharp cheddar, Manchego, Italian fontina, and Havarti cheeses are each a good match for this potato dish.

Sprinkle ½ cup shredded Gruyère or Swiss cheese over roesti in step 5 about 3 minutes before fully cooked on second side.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Roesti—a broad, golden brown cake of simply seasoned grated potatoes fried in butter—is hugely popular in Switzerland. We set out to master a stateside recipe with a crunchy, crisp exterior encasing a tender, creamy interior; one with good potato flavor, rich with butter. The goal here is to control the starch and the moisture, which tend to make roesti heavy and gluey. Some roesti are made with cooked potatoes, which makes these issues easier to control. However, we wanted a weeknight recipe that could be made with no advance planning so raw potatoes were a must. Rinsing and wringing out the potatoes helps.

SHRED, RINSE, AND SQUEEZE Excess starch and moisture in the potatoes will cause roesti to cook up gummy in the middle. The best way to remove both the excess starch and moisture is to shred the raw potatoes (we like the flavor of Yukon Golds best), rinse them, and then squeeze them dry in a kitchen towel. Even without rinsing, you can extract ¼ cup of liquid from 1½ pounds of potatoes.

ADD A LITTLE CORNSTARCH While rinsing away starch helps reduce gumminess, if you remove too much starch the potato cake isn’t cohesive and it will fall apart when sliced. Our solution is simple: Rinse the potatoes and then add a little cornstarch along with the salt and pepper. (This is much easier than trying to extract some of the potato starch from the rinsing liquid, as recommended in other recipes.) The added cornstarch also helps to crisp and brown the exterior of the potatoes.

COVER AT THE OUTSET Since you’re using raw potatoes, you need to make sure they are fully cooked by the time the exterior of the roesti is browned. Using the cover for the first few minutes traps steam and actually yields a lighter potato cake than leaving the cover off the whole time. (Loosely packing the potatoes into the pan is important—you need to give the steam a way to exit the roesti.)

DO THE FLIP While certain expert chefs may think nothing of flipping over a piping-hot skillet to turn a potato roesti out onto a plate, it can be a scary endeavor for mere mortals. A slipped grip or faltering wrist can send dinner crashing to the floor. Fortunately, there is a safer and less intimidating way to turn something over in a large skillet. Working with two plates, slide whatever you wish to flip onto one plate and top it with the other. Then, holding the two plates together, flip them over and slide the inverted food back into the pan to finish cooking.

ACTIVATING STARCHES AT WORK

ALIGOT, ROASTED POTATOES, HOME FRIES

We don’t always want to rid our dishes of starches. Sometimes we want to activate them—for cheesy mashed potatoes with an elastic texture, or roasted potato slices with great exterior browning. Some recipes call for manipulation to develop the starches in potatoes. By stirring, or simply roughing up the surface of our potatoes, we make the starch work to our advantage.

FRENCH-STYLE MASHED POTATOES WITH CHEESE AND GARLIC (ALIGOT)

SERVES 6

The finished potatoes should have a smooth and slightly elastic texture. White cheddar can be substituted for the Gruyère.

|

2 |

pounds Yukon Gold potatoes, peeled, cut into ½-inch-thick slices, rinsed well, and drained |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

6 |

tablespoons unsalted butter |

|

2 |

garlic cloves, minced |

|

1–1½ |

cups whole milk |

|

4 |

ounces mozzarella cheese, shredded (1 cup) |

|

4 |

ounces Gruyère cheese, shredded (1 cup) |

1. Place potatoes in large saucepan, add cold water to cover by 1 inch, and add 1 tablespoon salt. Partially cover saucepan and bring potatoes to boil over high heat. Reduce heat to medium-low and simmer until potatoes are tender and just break apart when poked with fork, 12 to 17 minutes. Drain potatoes and dry saucepan.

2. Transfer potatoes to food processor. Add butter, garlic, and 1½ teaspoons salt and pulse until butter is melted and incorporated into potatoes, about 10 pulses. Add 1 cup milk and continue to process until potatoes are smooth and creamy, about 20 seconds, scraping down sides halfway through processing.

3. Transfer potato mixture to saucepan and set over medium heat. Stir in cheeses, 1 cup at a time, until incorporated. Continue to cook potatoes, stirring vigorously, until cheese is fully melted and mixture is smooth and elastic, 3 to 5 minutes. If mixture is difficult to stir and seems thick, stir in 2 tablespoons milk at a time (up to ½ cup) until potatoes are loose and creamy. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Serve immediately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

Aligot is French cookery’s intensely rich, cheesy take on mashed potatoes. These potatoes get their elastic, satiny texture through prolonged, vigorous stirring—which can easily go awry and lead to a gluey, sticky mess. We monitor our stirring with caution to release just the right amount of starch for increasing the elasticity of the cheese.

START WITH YUKON GOLDS Russets have an earthy flavor we like in mashed potatoes, but with all the stirring this recipe requires they can be way too gluey. The Yukon Golds have good flavor, but a little less starch, so they are not as sticky or tacky in the finished dish. After making aligot with different potatoes, we found medium-starch Yukon Golds to be the clear winner.

CHUNK AND BOIL In the test kitchen, we’ve found that how you cook the potatoes for a regular mash is critical to their final texture. To avoid glueyness, we’ve gone so far as to steam as well as rinse the spuds midway through cooking to rid them of excess amylose, the starch in potatoes that turns them tacky. But because the potatoes are stirred so vigorously later (rough handling also bursts the granules that contain amylose, and the potato cells, releasing the starch into the mix), such treatment doesn’t matter. It’s fine to peel and boil the potatoes in chunks.

GET OUT THE FOOD PROCESSOR We use a food processor to “mash” our potatoes here. It most closely approximates the super-smooth puree produced by a tamis, a drum-size sieve, which is the traditional French tool used for this dish.

GO EASY ON BUTTER AND DAIRY This recipe needs less butter and lower-fat dairy (milk is fine) than regular mashed potatoes because of all the fat that will be supplied by the cheese. We add the butter (and garlic) to the mix in the food processor. Once the potato starches are coated with fat, we add the milk. The coating of butter helps to make the starch more compatible with the fatty cheeses so the starch molecules are better able to combine with the proteins. If milk is added first, the starch becomes so wet it resists interaction with the fatty cheese.

ADD TWO TYPES OF CHEESE The authentic cheese in aligot is tome fraîche, a spongy and elastic cow’s milk cheese not easily found in the United States. To replace this with something more readily available, we end up with two cheeses. Mozzarella gives the dish stretch, and Gruyère gives it a nutty flavor.

But is it the cheese alone that gives this dish its stretch? No. As it turns out, there is something different about the starch in potatoes that makes it possible to form the super stretch of aligot. Unlike the starch from other plants, the molecules in potato starch contain a small number of negative electrical charges. When combined with cheese proteins, parts of which contain positive electrical charges, an electrical bond between the two is created. Therefore, when curly amylose molecules bond with cheese proteins, the combination becomes very springy and stretchy.

STIR, STIR, STIR Stirring is the key to aligot, but it’s tricky. Too much and the aligot turns so rubbery that it is reminiscent of chewing gum. Too little and the cheese doesn’t truly marry with the potatoes for that essential elasticity. Three to five minutes is the magic number. During this time the amylose, released from the starch molecules, is binding with the proteins from the melted cheese, enhancing its stretch without causing glueyness.

CRISP ROASTED POTATOES

SERVES 4 TO 6

The steps of parcooking the potatoes before roasting and tossing the potatoes with salt and oil until they are coated with starch are the keys to developing a crisp exterior and creamy interior. The potatoes should be just undercooked when they are removed from the boiling water.

|

2½ |

pounds Yukon Gold potatoes, cut into ½-inch-thick slices |

|

|

Salt and pepper |

|

5 |

tablespoons olive oil |

1. Adjust oven rack to lowest position, place rimmed baking sheet on rack, and heat oven to 450 degrees. Place potatoes and 1 tablespoon salt in Dutch oven, add cold water to cover by 1 inch. Bring to boil over high heat, then reduce heat and gently simmer until exteriors of potatoes have softened but centers offer resistance when poked with paring knife, about 5 minutes. Drain potatoes well and transfer to large bowl.

2. Drizzle potatoes with 2 tablespoons oil and sprinkle with ½ teaspoon salt; using rubber spatula, toss to combine. Repeat with 2 tablespoons oil and ½ teaspoon salt and continue to toss until exteriors of potato slices are coated with starchy paste, 1 to 2 minutes.

3. Working quickly, remove baking sheet from oven and drizzle remaining 1 tablespoon oil over surface. Carefully transfer potatoes to baking sheet and spread into even layer (place end pieces skin side up). Bake until bottoms of potatoes are golden brown and crisp, 15 to 25 minutes, rotating baking sheet after 10 minutes.

4. Remove baking sheet from oven and, using metal spatula and tongs, loosen potatoes from pan and carefully flip each slice. Continue to roast until second side is golden and crisp, 10 to 20 minutes longer, rotating baking sheet as needed to ensure potatoes brown evenly. Season with salt and pepper to taste, and serve immediately.

WHY THIS RECIPE WORKS

For roasted potatoes with the crispiest exterior and creamiest interior, we had to find the right spud, the right shape, and the right cooking method. Parcooking is key, as gently simmering the potatoes draws starch and sugar to the surface and washes away the excess quickly. In the oven, the starch and sugar will harden into a crisp shell, especially after we rough up the surface of the potatoes, which helps to speed up evaporation during roasting, making the crusts even crisper.

YUKON GOLDS ARE BEST Most recipes rely on long cooking times for crisp roasted potatoes, yielding tough, leathery exteriors and dried-out, mealy interiors. With the goal of creating a really crisp roast potato with a creamy interior, we tested different types of potatoes. For velvety interiors, the ideal potato has high moisture and low starch. But the ideal potato for a crisp exterior has low moisture and high starch. Russets and red potatoes give either the exterior or the interior too much weight. Yukon Golds are the perfect compromise choice—enough moisture so the interior is creamy, enough starch for a crispy exterior.

CUT INTO DISKS We cut our potatoes into disks rather than chunks because the disks have much more surface area for maximum browning. They also flip easily, and we can be sure that each side will sit flush against the pan.

PARCOOK THE POTATOES For a potato to brown and crisp, two things need to happen, both of which depend on moisture. First, starch granules in the potatoes must absorb water and swell, releasing some of their amylose. Second, some of the amylose must break down into glucose, a type of sugar. Once the moisture evaporates on the surface of the potato, the amylose hardens into a plasticlike shell, yielding crispness, and the glucose darkens, yielding an appealing brown color. In the dry heat of the oven, this is a lengthy process because the starch granules swell slowly, releasing little amylose. In contrast, parboiled potatoes are swimming in the requisite moist heat, releasing lots of amylose on the surface of the potato. By the time parcooked spuds get transferred to the oven, they are ready to begin browning and crisping almost immediately.

HANDLE ROUGHLY Potatoes that are parcooked brown faster in the oven. But potatoes that are parcooked and “roughed up” by being tossed vigorously with salt and oil brown even faster. It’s all a matter of surface area. Browning or crisping can’t begin until the surface moisture evaporates and the temperature rises. The parcooked, roughed-up slices—riddled with tiny dips and mounds, the salt causing added friction—have more exposed surface area than the smooth raw slices and thus more escape routes for moisture.

USE HOT OVEN, HOT BAKING SHEET Preheat the baking sheet used for the potatoes along with the oven. This allows for a shorter roasting time. A shorter time in the oven allows more retention of moisture in the potato innards, resulting in a creamier texture.

HOME FRIES

SERVES 6 TO 8

Don’t skip the baking soda in this recipe. It’s critical for home fries with just the right crisp texture.

|

3½ |

pounds russet potatoes, peeled and cut into ¾-inch dice |

|

½ |

teaspoon baking soda |

|

3 |

tablespoons unsalted butter, cut into 12 pieces |

|

|

Kosher salt and pepper |

|

|

Pinch cayenne pepper |

|

3 |

tablespoons vegetable oil |

|

2 |

medium onions, cut into ½-inch dice |

|

3 |

tablespoons minced fresh chives |

1. Adjust oven rack to lowest position, place rimmed baking sheet on rack, and heat oven to 500 degrees.

2. Bring 10 cups water to boil in Dutch oven over high heat. Add potatoes and baking soda. Return to boil and cook for 1 minute. Drain potatoes. Return potatoes to Dutch oven and place over low heat. Cook, shaking pot occasionally, until any surface moisture has evaporated, about 2 minutes. Remove from heat. Add butter, 1½ teaspoons salt, and cayenne; mix with rubber spatula until potatoes are coated with thick starchy paste, about 30 seconds.

3. Remove preheated baking sheet from oven and drizzle with 2 tablespoons oil. Transfer potatoes to baking sheet and spread into even layer. Roast for 15 minutes. While potatoes roast, combine onions, remaining tablespoon oil, and ½ teaspoon salt in bowl.

4. Remove baking sheet from oven. Using thin, sharp metal spatula, scrape and turn potatoes. Clear about 8 by 5-inch space in center of baking sheet and add onion mixture. Roast for 15 minutes.

5. Scrape and turn again, mixing onions into potatoes. Continue to roast until potatoes are well browned and onions are softened and beginning to brown, 5 to 10 minutes longer. Stir in chives and season with salt and pepper to taste. Serve immediately.

Despite the cozy image conjured by the name, few people actually make home fries at home. That’s probably because producing the perfect dish—a mound of golden-brown potato chunks with crisp exteriors and moist, fluffy insides dotted with savory onions and herbs—calls for more time, elbow grease, and stovetop space than most cooks care to devote to the project. We simplify our home fries with a super-fast precook in boiling water (with baking soda!), and some time in a hot oven.

CHOOSE RUSSETS When developing this recipe, we tested the three main kinds of potatoes: waxy, low-starch red-skinned spuds; all-purpose, medium-starch Yukon Golds; and floury, high-starch russets (see concept 25). Tasters almost universally rejected the texture of the red-skinned potatoes as too waxy for home fries. Though some praised the creaminess of the Yukon Golds, the majority preferred the earthy flavor of russets. After all, the higher starch content of russets does make for a crustier exterior—especially when manipulated.

PARBOIL WITH BAKING SODA A very quick jaunt in boiling water—with baking soda—is the secret to the success of these home fries. Because the russets are so starchy, if they are cooked all the way through before going against high heat, they will absorb all the oil before beginning to brown. The short blanch (just 1 minute) is an effective way to break down just the very exterior of the potato. This is possible because of the baking soda, which speeds up the softening process (see “Baking Soda for Brown Crusts”) and therefore exaggerates the differences in doneness between the exterior and the interior of the potatoes. The thin outer layer of blown-out, starchy potato will brown thoroughly in the oven, while the raw middle will stay moist.

SALT THE EXTERIOR Tossing the drained parcooked potato chunks with butter and salt before placing them on the baking sheet helps with the browned exterior. The coarse salt roughs up the surface of the potatoes so that moisture evaporates faster, leading to better browning.

ROAST IN THE OVEN These home fries might as well be called home-roasted potatoes, because we do just that. Unable to ignore the fact that the oven is best for large batches, we choose high-temperature roasting over making many batches in a skillet.