Chapter 10

Coming Into Port – Week Seven: Looking After Your Own Wellbeing

In This Chapter

Being proactive in your own treatment and restoration

Being proactive in your own treatment and restoration

Handling everyday negative experiences

Handling everyday negative experiences

Bringing enjoyment into your life

Bringing enjoyment into your life

Protecting yourself

Protecting yourself

No doubt you know just how easily you can get caught up in the whirl of daily duties and activities, leaving no time for yourself. And when you do get a moment to relax, the temptation is to spend it in non-productive or even unhealthy ways, such as slumping in front of the goggle-box. As a result, you need to ensure that you create time that’s quite deliberately reserved for your wellbeing, because if you put things off until time appears miraculously, you’re going to have a long, long wait!

The key aim of this chapter is to encourage you to reconnect to activities and interests in your life that you may have given up or put on hold in order to create more space for work and responsibilities. I ask you to review your daily activity and work schedule, decide which actions drain and which recharge you, spend a few minutes each evening on those that positively benefit you and work on accepting that you’ve no reason to beat yourself up just because you’re taking a little time for yourself. I also provide some great practical exercises for dealing with everyday hassles and problems and encourage you to have fun and enjoy mindful living throughout the day.

If you feel resistance – perhaps thinking that you’ve no time to spare and can barely fit in your daily meditation as it is – please don’t give in to the urge to avoid reading any further or to drop this book accidentally into the bath or leave it on the bus! This chapter is an essential part of your mindfulness practice, so remember to observe any such reactions mindfully so that you can catch yourself before you make any rash decisions.

Getting Your Bearings on the Course

If you started your mindfulness programme because it seemed the ‘in-thing’ to do and looked straightforward, by this point in the eight-week course you no doubt know that mindfulness isn’t as effortless and uncomplicated as you thought. Your mind wants to keep busy all the time and tends to lean towards and connect to pointless ruminations. A wise American psychologist once said that ‘negative thoughts are like Velcro and positive thoughts are like Teflon’: you attach to the negative thoughts all too easily! The problem is that these ruminative patterns rarely concern themselves with the joy and adventure of life.

For this chapter to yield the best results, you should already trust in mindfulness enough to implement it into your life, because only regular practice allows you the chance to feel equanimity and peace. As part of this preparation, I suggest that you:

Design and set up a personal, designated, conducive meditation space, as I describe in Chapter 4, in which you can feel calm and be left undisturbed. Also, find and stick to the best time of the day to meditate for you.

Design and set up a personal, designated, conducive meditation space, as I describe in Chapter 4, in which you can feel calm and be left undisturbed. Also, find and stick to the best time of the day to meditate for you.

Become familiar with the idea of ‘non-doing’; in other words just being with the breath and scanning your body mindfully (see Chapters 4, 5, and 6).

Become familiar with the idea of ‘non-doing’; in other words just being with the breath and scanning your body mindfully (see Chapters 4, 5, and 6).

Read Chapter 7 and work on gaining an understanding of stress and how mindfulness can combat it.

Read Chapter 7 and work on gaining an understanding of stress and how mindfulness can combat it.

Taking Positive Steps to Look After Yourself

What you do with your time, moment to moment, can affect your general welfare and your ability to respond competently to the challenges you inevitably come across in the course of your life. Amazingly, many people truly believe that they don’t have time to pamper themselves or look after themselves as they would look after a friend, child or pet. I’m not talking about ruining yourself through excessive gratification or reckless over-indulgence, but instead that common belief that you shouldn’t do something you enjoy doing – at least not too often. Often, this belief causes guilt to arise when you do something you want to do.

Evidence shows that mindfulness helps people to recover from burn-out and illnesses of both body and mind. This evidence is why the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines and the Mental Health Foundation (UK) promote and encourage people to develop mindfulness skills, so that they can prevent illness or help themselves to heal more quickly (check out the sidebar ‘Ahhh, that’s NICE!’ for more details).

Taking a break: Fixing your focus mindfully

Throughout this book I describe a good number of meditations and daily mindfulness exercises for you to practise in your everyday life. Rather like brushing your teeth, having a shower or eating regularly, the need to engage in your chosen mindful routines is important.

Here’s an extended version of the ten-minute mind-movie viewing meditation in Chapter 6, which you can do anywhere, at any time, in any position. This time, I invite you to choose something that initially appears to have no particular interest, such as a blank wall, a curtain with a repetitive pattern or a piece of rubbish like an old cloth. These viewing objects do not present any beauty or interest at first, but see what you can really make out when you look more deeply. Even if you find nothing outstanding, check whether your body sensations or emotions vary from the beginning of the practice to the end of it. Consider thinking about whether the simple act of watching something can change the experience of the present moment and the energy flow in your body.

When you feel ready, please:

1. Ground yourself by feeling into your body. Focus on three points of contact: your big toe, the little toe and your heel, which together act like a strong tripod of safety. Bring your awareness to your body sensations and emotions and mentally note down what you find there. Are you calm or excited, joyful or irritable? Are you feeling tension anywhere in your body or do your muscles feel loose? Remember that no right or wrong way of being exists. Simply acknowledge what you find without attaching any value or judgement to it.

1. Ground yourself by feeling into your body. Focus on three points of contact: your big toe, the little toe and your heel, which together act like a strong tripod of safety. Bring your awareness to your body sensations and emotions and mentally note down what you find there. Are you calm or excited, joyful or irritable? Are you feeling tension anywhere in your body or do your muscles feel loose? Remember that no right or wrong way of being exists. Simply acknowledge what you find without attaching any value or judgement to it.

2. Locate a window frame, a plant or an object at home or in your office; or stop in front of a shop window, a tree, bush or any other interesting item. Now resolve in your mind that for the next few minutes you’re going to gaze only at this one chosen viewpoint.

3. Resolve not to let your eyes wander. See how much detail you can find in this one area of focus. Sometimes things change within the frame much more that you may expect (for example, when you look out of a window frame, different visitors come and go). Even if you choose an empty white wall, you can still find little cracks, dots, shadows and so on. Bring patience and curiosity to this practice and don’t force your eyes to deal with an overload of information.

4. Re-ground yourself before finishing the exercise. You may well feel more grounded and connected to life and in yourself. You may even experience a sense of solidity, a tingling sensation or feel as if you’ve had a weight lifted off your shoulders.

This meditation can be an important step to caring better for yourself. Taking a few minutes to allow your sense of seeing to rest on a small detail of life relieves your eyes from the relentless overload of technology and visual stimulation.

Maintaining and developing your practice for your benefit

Your mind wants to keep continually busy with thoughts and worries, and so on. But these ruminations often revolve around what you have to do or think you have to do, the things that went wrong and the things that may go wrong. Regular mindfulness practice offers you a whole new experience of life; a kind of childlike curiosity and connectedness with being alive and a moment-to-moment encounter with tiny little aspects of life.

Regular practice is crucial here, as is noting down in your mindfulness diary what changes you observe in your daily life, behaviour, thinking patterns, use of language, and so on. For some examples, take a look at the sidebar ‘Noting progress for motivation’. Let these examples inspire and motivate you. Write down a list of your own ideas about changing everyday behaviour and actions by applying mindfulness to them.

Beginning your day with a treat

In Chapter 6, I suggest that you start your day with a delicious mindfulness breakfast with your favourite options and your own ingredients. To help you generate ideas, peruse my personal idea of a mindful breakfast:

1. Prepare the coffee, making sure to smell the ground powder before adding hot but not boiling water to it. Breathe in deeply and enjoy!

2. Heat the milk (semi-skimmed or full cream) and just before it boils, take it off the stove.

3. Put the croissant on top of a toaster and keep turning it over so it gets crusty but doesn’t burn; continue until it smells lovely and irresistible.

4. Start frothing the milk in the small pan – always start with the top layer and work your way down.

5. Pour the coffee into your favourite mug, add sugar if you want and then, spoon by spoon, add the milk into the mug, stirring it in gently and at the end add the frothy part on the top.

6. Add a crown of powdered or grated chocolate on top of the frothy peak if you desire.

7. Find a perfect seat in the kitchen or dining area and bring in the café au lait and croissant.

8. Dunk the croissant mindfully into the coffee, let it soak up a bit of the brew and immediately bite off a chunk soaked in frothy coffee and still crusty at the top.

9. Chew and soak up the flavours of coffee, sugar, frothy milk and crispy croissant.

10. Really taste each bite – it’s a heavenly concoction; enjoy the smell and notice how you’re feeling in your body while engaging in this joyous ritual.

If you can start every day with a mindful breakfast – joyfully engaging with it, using all your senses and tasting it in an unrushed way – the likelihood is that you can take this sentiment and energy into the rest of your day. Yes, maybe you need to get up 15 minutes earlier, but it really is worth it.

Please don’t forget to write down your experiences in your diary.

Rebalancing Your Daily Life

Sometimes you can have sincere intentions of introducing a new idea into your life, but fate seems against you. Hindrances of all different kinds can prevent you from practising mindfulness effectively. Well, here’s the good news! There’s no right or wrong way of doing it, only your way!

Mindfulness is so adaptable that you can use it to rebalance your life more positively and even to remove the hindrances that get in the way of you practising mindfulness. How convenient!

Identifying your daily drainers and possible rechargers

Often you can feel listless because all your energy is invested in the things that ‘matter’: work, status, bonuses, and so on. From time to time, you may ask yourself, ‘is this really it?’

In all likelihood, you always feel like you’ve too much to do in too little time. People nowadays have longer working hours, longer commutes and still have to deal with everything concerning the family home (in the past people often lived in union with grandparents, aunts, uncles, and so on and everybody chipped in). The relative wealth in monetary terms has a high cost in relation to day-to-day living. You’re also constantly challenged by technological advances which, although assisting you in many ways, require you to use more time and energy in order to use them effectively than you’re likely to save.

And the best place to start changing is right here with the person who’s known and cared for you all your life: you! (Have you met?)

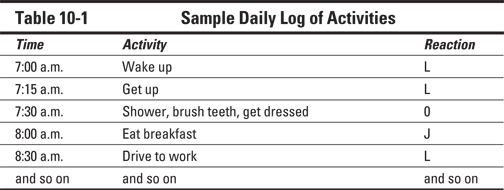

1. Write down on a sheet of paper or in your mindfulness diary a list of your daily activities, including the time of day that you performed them (be as specific as possible). Begin with waking up in the morning, continue through your day at work and go all the way through to the evening when you go to bed. Please try to keep this daily log of activities to no more than 20 entries.

2. Draw an image or a symbol next to each activity, indicating whether you like it and find it nourishing, feel neutral about it, or feel negatively about it or that it depletes you of energy and positivity. For example, J for positive, L for negative and 0 for neutral – use whatever symbols make the most sense to you.

3. Go back and mindfully ask yourself which negative activity (or indeed neutral one) you can change into a positive one without too much effort. For example, perhaps you can make waking up more enjoyable: count your blessings, think about something you’re grateful for, and go to the window and open it, taking a few mindful breaths of fresh air.

4. Think about what other mindful activities you can implement to increase the nourishing aspects of your day. You can perhaps decide to walk to work mindfully, and let any sound be the sound of mindfulness inviting you to stop and take a mindful breath. Or you may be able to have a proper lunch break in silence or take a co-worker with you and explore nearby lunch options. A brief walk, fresh air, natural light and actually eating when you’re supposed to be eating can be a real mood-lifter.

Table 10-1 shows what your daily activities log may look like.

This exercise can help you re-evaluate those activities that you may consider necessary but for which you can pay the high price of stress, depression and burn-out, and immune disorders and other physical forms of illness. I describe the physical illnesses in more detail in Chapter 7.

Alleviating feelings of anger

Accepting such negative emotions as part of you may be a little odd, but the truth is that humans become angry and bad-tempered. In a recent interview, the Dalai Lama admitted that he’d occasionally been trapped by anger and bad-temper. He was still his usual self and laughing when he explained that his team knew well how he sometimes displayed these destructive emotions. Perhaps he laughed because he’s so very much aware of his humanity.

So before you can accept something and then respond wisely, the first step is always to know that it exists. Then, if anger and bad-temper occur more regularly than usual, you can take it as a sign that you’re stressed or mildly depressed. Allow your awareness to use these emotions as a guide, and then mindfully search for alternatives within your heart.

Just For Me

What if a poem were just for me?

What if I were audience enough because I am,

Because this person here is alive, is flesh,

Is conscious, has feelings, counts?

What if this one person mattered not just for what

She can do in the world

But because she is part of the world

And has a soft and tender heart?

What if that heart mattered,

if kindness to this one mattered?

What if she were not distinct from all others,

But instead connected to others in her sense of being distinct, of being alone,

Of being uniquely isolated, the one piece removed from the picture

All the while vulnerable under, deep under, the layers of sedimentary defence.

Oh let me hide

Let me be ultimately great,

Ultimately shy,

Remove me, then I don’t have to. . .

be . . .

But I am.

Through all the antics of distinctness from others, or not-really-there-ness, I remain

No matter what my disguise

Genius, idiot, gloriousness, scum

Underneath, it’s still just me, still here,

Still warm and breathing and human

With another chance simply to say hi, and recognise my tenderness

And be just a little bit kind to this one as well,

Because she counts, too.

—Anon

Stabilising your mood

In order to (re)balance your mood, you really need to balance your daily activities: ask yourself how you can take care of yourself, limit activities that bring you down and accept areas in your life that, at least for now, you simply can’t change. Here are a few other suggestions for those difficult moments:

When you feel overwhelmed by demands, follow the coping breathing space meditation from Chapter 8.

When you feel overwhelmed by demands, follow the coping breathing space meditation from Chapter 8.

Ground yourself when your brain seems to shut down. Feel your feet firmly rooted; sense three points of contact – your big toe, your little toe and your heel. This grounding helps to give you a sense of steadfastness and solidity. You’re likely to feel much clearer in your thinking and more in control of the situation.

Ground yourself when your brain seems to shut down. Feel your feet firmly rooted; sense three points of contact – your big toe, your little toe and your heel. This grounding helps to give you a sense of steadfastness and solidity. You’re likely to feel much clearer in your thinking and more in control of the situation.

Ask yourself, when the going gets rough, how will I feel about this situation tomorrow, in a month in a year from now. Perspective is a great healer.

Ask yourself, when the going gets rough, how will I feel about this situation tomorrow, in a month in a year from now. Perspective is a great healer.

Book a home treatment (such as massage, Pilates or reflexology, for example) or personal training session – many complimentary therapists and personal trainers are nowadays perfectly happy to come to your home. It can be so lovely not having to go out again after a treatment or training session, particularly if you’ve a long commute to work. You can stay put and yet still engage in a healthy activity.

Book a home treatment (such as massage, Pilates or reflexology, for example) or personal training session – many complimentary therapists and personal trainers are nowadays perfectly happy to come to your home. It can be so lovely not having to go out again after a treatment or training session, particularly if you’ve a long commute to work. You can stay put and yet still engage in a healthy activity.

Call, or even better, invite round a friend. Humans are pack animals and socialising and meeting others is important.

Call, or even better, invite round a friend. Humans are pack animals and socialising and meeting others is important.

Do something manual and creative such as kneading dough, arranging plants, drawing a picture or playing a musical instrument. Stimulating the creative mind balances out the overactive left hemisphere of your brain.

Do something manual and creative such as kneading dough, arranging plants, drawing a picture or playing a musical instrument. Stimulating the creative mind balances out the overactive left hemisphere of your brain.

Ask yourself whether a challenge can wait until tomorrow.

Ask yourself whether a challenge can wait until tomorrow.

Look at photographs you’ve collected over the years.

Look at photographs you’ve collected over the years.

Just take care of now – this moment is precious if you really allow yourself to think about it; the present moment is part of your life.

Just take care of now – this moment is precious if you really allow yourself to think about it; the present moment is part of your life.

Having Fun for Fun’s Sake

You can use only one of your two nervous systems (which I describe in more detail in Chapter 7) at any one time:

The sympathetic nervous system: The ‘fight-or-flight’ system that releases stress chemicals and is essential for survival.

The sympathetic nervous system: The ‘fight-or-flight’ system that releases stress chemicals and is essential for survival.

The parasympathetic nervous system: The ‘peace’ system and the one in which ideally you want to spend most of your life.

The parasympathetic nervous system: The ‘peace’ system and the one in which ideally you want to spend most of your life.

Laughter automatically switches on the second system, thus making humour a great stress releaser: you laugh and feel a little better.

Treating yourself

Have a ‘Happy Unbirthday’ (as Lewis Carroll says in Alice in Wonderland) 364 days a year. Every day is worth celebrating – as indeed is every moment.

Simple actions are a good start, like having your first hot drink in the morning and taking real time to enjoy it, while looking out into your garden if you have one. Or having a hot bath or massage, going to a movie or out for a lovely meal, or walking in the countryside.

And don’t forget being generous towards other people, such as taking time to help in a soup kitchen at Christmas or donating to a good cause. Kindness nurtures kindness.

Not overindulging

Here’s a little pinch of wisdom: looking after yourself is great, really! What isn’t helpful, however, is to make any of your chosen tension-releasing activities absolute must-haves.

If you book a massage and suddenly receive a text telling you that the masseuse is unwell, rather than feeling stroppy and letting self-pity ride you, try to be mindful of your disappointment and think of an alternative activity. Or perhaps find a simple act right there and then that gives you a sense of wellbeing, such as putting your feet up and reading a novel in the middle of the day, even if loads of housework still needs to be done. You know what? It’ll still be there in half an hour.

Furthermore, bear in mind that pastimes such as gambling with friends, video games and watching television can also become unhealthy attachments. You aren’t going to disappear in a puff of smoke if you can’t watch this one favourite TV programme, or eat the chocolate you put in the fridge that disappeared because another family member has eaten it!

Dealing with Threats to Your Wellbeing

Over time, and with continued mindfulness practice, you become more and more able to respond wisely to unexpected occurrences. Don’t worry about turning into a perfectly functioning machine (as you know, machines also malfunction), but do notice as you move beyond being a prisoner of your old patterns and fears. You can truly build enough new, compassionate, moment-to-moment patterns of thinking and behaving that can guide you in taking the right actions. Nobody else has to tell you what to do and how to respond. Your wise mind (in other words, your brain and heart in unity) guides you.

When you have even a sniff of this experience, you don’t want anything to disrupt it. So, in this section I provide tips on tackling impediments to your wellbeing.

Remembering the good

If you feel that your mental and/or physical health is beginning to deteriorate, your first point of action needs to be the coping breathing space meditation (in Chapter 8). It can help you to see deeply what’s amiss, what feels out of balance and how you may proceed.

Your next point of action, once you have started using regular mindfulness interventions, is to focus on your ‘EGS’, which stands for Enjoyment, Gratitude and Satisfaction. Ask yourself the following questions for each category:

Enjoyment: ‘What did I enjoy today?’ For example, ‘I enjoyed birdsong, a nice meal, a hot bath, making my friend laugh, a lovely sunset or rainbow’, and so forth.

Enjoyment: ‘What did I enjoy today?’ For example, ‘I enjoyed birdsong, a nice meal, a hot bath, making my friend laugh, a lovely sunset or rainbow’, and so forth.

Gratitude: ‘What am I grateful for?’ For example, ‘I’m grateful for my legs, my eyes, my home, this apple, my friends’, and so on.

Gratitude: ‘What am I grateful for?’ For example, ‘I’m grateful for my legs, my eyes, my home, this apple, my friends’, and so on.

Satisfaction: ‘What am I satisfied with?’ For example, ‘I’m satisfied with polishing my shoes, taking out the rubbish, getting rid of old clothes or newspapers’, and so on.

Satisfaction: ‘What am I satisfied with?’ For example, ‘I’m satisfied with polishing my shoes, taking out the rubbish, getting rid of old clothes or newspapers’, and so on.

Write down your regular EGSs every evening (a minimum of one per category) and immediately in times of need. Doing so helps you to incline your mind towards that which is wholesome, nourishing and energising.

I recommend that you write them down by hand in your diary because:

Writing things down by hand stimulates both brain hemispheres.

Writing things down by hand stimulates both brain hemispheres.

If you write things down last thing at night, it closes your thinking process on an optimistic note.

If you write things down last thing at night, it closes your thinking process on an optimistic note.

In an emergency, you still remember those exercises you practise most regularly (that is, the coping breathing space and EGSs).

In an emergency, you still remember those exercises you practise most regularly (that is, the coping breathing space and EGSs).

Your diary helps you to remember all the good things in your life even when life is tough. Everything passes at last and rainbows often follow storms.

Your diary helps you to remember all the good things in your life even when life is tough. Everything passes at last and rainbows often follow storms.

Finding the right response

Life is unpredictable – joy, suffering and equanimity are all available to you, but never on demand. Therefore, being with ‘what is’ is really important. Becoming disappointed about something not arriving or occurring is only natural, but chewing over the why, how, when, and so on only deepens the ruminative downward spiral towards despair.

Linking your actions to your moods

Linking your actions to your moods can only be helpful if you understand that everything is transient and passes in time. Feeling upset because your friend doesn’t show up for an arranged meeting, for example, is generally understandable. Shouting at her when she eventually manages to get in touch may prove to be the opposite of what’s helpful for gaining perspective towards what really happened. What if her mobile had run low and she was involved in an accident, hopefully only as a witness. She may not share it with you if she feels you’ve already judged her.

So let mindful action and speech be your guides. When she turns up or phones, focus mindfully on your breathing and ground yourself by feeling your feet firmly connected to the surface you’re standing or sitting on. Then listen with awareness and compassion to the story she has to tell. Thereafter decide, ideally without judgement, whether her actions make sense to you or whether you need to tell her how worried or disappointed you were. She’s likely to listen more readily if she feels you haven’t jumped to a conclusion and is likely to respond empathically to your pain if she can really hear it rather than your self-pitying tirade!

Improving how you feel through what you do

When you cope with mindfulness as your guide in all interactions with others and also yourself, you find more often than not that the heavy cloud of low, anxious or angry mood lifts and your dealings with fellow beings appreciably improves.

It does take time, but moment by moment you notice a softening towards your own flaws and those of others. With this softening, you may also observe a gentle but ongoing embrace of life’s experiences, even those you may not have handled well in the past. There’s no guarantee of significant change, but there will be a general tendency towards kindness.

Sitting with spacious awareness

Choiceless awareness may create a quality of mind that’s free from making judgements, decisions or generating commentary as it meets with sense experiences. It assists the mind to respond to each new moment without the burden of its past history or of making future projections. When the mind no longer clings to anything, not even to the idea of ‘not clinging’ (non-attachment), you may realise, suddenly or gradually, that you already are truly what you’ve been searching for.

Buddhists believe that nature resides in everyone already. In layperson’s terms, this belief means that all you are (even the imperfect, stumbling actions you engage in) already holds the key to beauty and kindness. This concept may be an odd one to grasp, but think of it as having the intention to achieve a greater sense of spaciousness and sitting with determination, while also being open to different ‘anchors of attention/awareness’ (a concept I describe more in Chapter 4).

1. Try to let go of any specific focus of alertness – just sit with awareness.

2. Allow whatever thoughts and so on arise simply to be here, now, in this moment.

3. Notice any messages or insights that arise, and if you choose make a mental note of them without taking it any further right now.

4. Observe recurring patterns of actions and reactions of the mind (thoughts and emotions) and the body (such as aversion or tensing up).

5. Return to the breath as an anchor if your mind feels too unsettled.

6. Finish when it feels right, trusting your inner clock as to how long this meditation lasts.

Reviewing Your Accomplishments This Week

Please take a look at the following questions to help you appraise your wellbeing practices:

Have you been able to accept the importance of proactively looking after yourself and put the lessons into practice too (as I discuss in the earlier section ‘Taking Positive Steps to Look After Yourself’)?

Have you been able to accept the importance of proactively looking after yourself and put the lessons into practice too (as I discuss in the earlier section ‘Taking Positive Steps to Look After Yourself’)?

Are you continuing to practise the exercises in the earlier section ‘Rebalancing Your Daily Life’ to assist you with everyday experiences?

Are you continuing to practise the exercises in the earlier section ‘Rebalancing Your Daily Life’ to assist you with everyday experiences?

Are you managing to bring more moments of pure fun into your life (see the section ‘Having Fun for Fun’s Sake’ earlier in this chapter)?

Are you managing to bring more moments of pure fun into your life (see the section ‘Having Fun for Fun’s Sake’ earlier in this chapter)?

Do you feel more confident about protecting your wellbeing after reading the preceding section ‘Dealing with Threats to Your Wellbeing’?

Do you feel more confident about protecting your wellbeing after reading the preceding section ‘Dealing with Threats to Your Wellbeing’?

Kindness, compassion and mindful living reduce the probability of ill health and increase a sense of wellbeing, connectedness and belonging within yourself and to the world around you. The mindset I ask you to adopt in this chapter is one of nourishing and replenishing yourself with kindness, generosity and patience. Take great care of yourself, and remember that your wellbeing is vital to a great life!

Kindness, compassion and mindful living reduce the probability of ill health and increase a sense of wellbeing, connectedness and belonging within yourself and to the world around you. The mindset I ask you to adopt in this chapter is one of nourishing and replenishing yourself with kindness, generosity and patience. Take great care of yourself, and remember that your wellbeing is vital to a great life! Whatever you do, remember that anything that holds you prisoner is, in the long run, not healthy.

Whatever you do, remember that anything that holds you prisoner is, in the long run, not healthy. This exercise, which you can also listen to in Track Eight, is also often called ‘choiceless awareness’. In this practice, you don’t anchor your awareness in any particular way. It’s a free-flowing meditation, which has its own beauty and is also different every time you practise it. You can see it as allowing the mind to observe whatever surfaces during the meditation. Issues that have been deeply repressed may begin to rise to the surface, providing you with the opportunity to address them consciously. By recognising your self-destructive patterns, their power to control your behaviour diminishes.

This exercise, which you can also listen to in Track Eight, is also often called ‘choiceless awareness’. In this practice, you don’t anchor your awareness in any particular way. It’s a free-flowing meditation, which has its own beauty and is also different every time you practise it. You can see it as allowing the mind to observe whatever surfaces during the meditation. Issues that have been deeply repressed may begin to rise to the surface, providing you with the opportunity to address them consciously. By recognising your self-destructive patterns, their power to control your behaviour diminishes.