KIDS OF KABUL

LIVING BRAVELY THROUGH

A NEVER-ENDING WAR

DEBORAH ELLIS

GROUNDWOOD BOOKS / HOUSE OF ANANSI PRESS

TORONTO BERKELEY

Text copyright ©2012 by Deborah Ellis

Published in Canada and the USA in 2012 by Groundwood Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

This edition published in 2012 by

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

www.houseofanansi.com

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Ellis, Deborah

Kids of Kabul : living bravely through a never-ending war / Deborah Ellis.

eISBN 978-1-55498-203-5

1. Children—Afghanistan—Juvenile literature. 2. Children and war—

Afghanistan—Juvenile literature. 3. Afghan War, 2001- —Children—Juvenile literature. I. Title.

HQ792.A3E55 2012 j305.235092’2581 C2011-906638-6

Front cover photo: Gilles Bassignac / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Back cover photo: Paula Bronstein / Getty Images

All other photos are courtesy of the author.

Design by Michael Solomon

![]()

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF).

To the next generation of survivors

Introduction

I am a feminist, which means I believe that women are of equal value to men. I am from Canada, a country not without its struggles but where women and girls are not limited — in theory — by the fact that they are female. When I heard about the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 1996, and the crimes they perpetrated against women and girls, I decided to get involved.

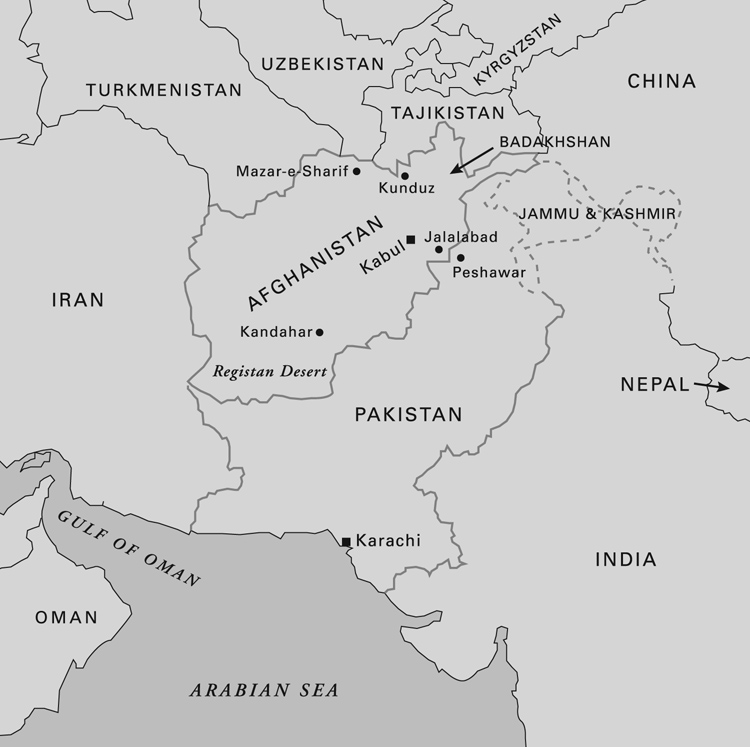

This started me on a journey that has taken me from Afghan refugee communities in Canada to the muddy tent camps in Pakistan and the decrepit Soviet workers’ holiday hotels outside Moscow that, ten years ago, served as encampments for Afghan and other refugees. It is a journey that has spawned four books: an adult book (Women of the Afghan War) and three novels about children under the Taliban, the last one published in 2003.

And now I’ve gone back.

Afghanistan has been at war for decades. It has been used by the world’s great powers in their struggles against each other. One such struggle produced the Taliban government, which, at an earlier stage of the war, had been supported by the United States. Among other things, the Taliban regime was brutally repressive toward women. The Taliban also harbored al-Qaeda, the terrorists who were responsible for the September 11th attacks on the United States in 2001. The war that followed initially overthrew the Taliban government but has continued for the past eleven years.

The real losers are the Afghan people, especially the women and children. Their daily lives are still threatened by suicide bombings, armed conflict and other forms of violence, and even Kabul, the capital city, is not secure. Tens of thousands of Afghans have died since 9/11 — many, many more than died in the twin towers. People have been injured, maimed, displaced and terrorized. People are hungry, people are fleeing, and families are separated from their homes and from each other. Refugees who left their homes as long as twenty years ago live in informal camps where they have no services other than those offered by one or two NGOs. This means there are still millions of internally and externally displaced Afghans living in miserable conditions without water, plumbing or electricity. The billions and billions of dollars spent on the war, which might have been spent on education, health care, housing and rebuilding a civil society, have been spent on weapons.

So has anything been gained?

For some young people life has improved, and they are grabbing hold of every opportunity with both hands. Though more than half the children in Afghanistan still have no access to schooling, those who do study hard. When they are allowed to play sports, they play hard. The lucky ones who have money and who live in Kabul and a few other cities are reaching out to each other and to the world, using social media and new technologies. Some institutions are bringing them into contact with music and art. And they are finding ways to take their considerable energies and talents into public life to move their country forward.

The interviews in this book were conducted over the weeks I was in Kabul early in 2011. Many of the young people spoke only Afghan languages, so their words were translated into English for me by an interpreter — the same interpreter for many of the interviews.

Children’s playground in a park just north of Kabul.

Although I usually travel alone, this time I traveled with Janice Eisenhauer and Lauryn Oates from Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan. Many of the places I visited were involved with projects funded by Women for Women. Due to the security situation, I did not travel beyond Kabul.

It is possible to read the interviews in this book and come away feeling hopeful about the future of these kids and the future of their country. It is good to be hopeful, and if the future could be in the hands of this generation of young people, with their eagerness, openness and determination, then Afghanistan could indeed be a garden again.

Sadly, the old way of doing things — the way of corruption and killing and suspicion and venal international interests — seems to be gaining the upper hand. But there is no question that we must reach out and support these young people and the Afghan organizations that work with them. Only through work at the grassroots level can the patient day-to-day of rebuilding take place.

We have to stand together to move forward. Anything we can do to connect with Afghan people, to appreciate what they have been through and what they are capable of, and to assist them in getting the education they need to rebuild their own country will be a step away from madness and pain, and a step toward the sunshine.

Deborah Ellis

2012

Faranoz, 14

During the Taliban regime, schools for girls were closed, and women were forbidden from attending university. Extreme poverty coupled with decades of war and chaos have left the country with high rates of illiteracy. According to the United Nations Human Development Report of 2008, only 28 percent of Afghan adults can read and write. That number drops to 13 percent for women.

Since the fall of the Taliban, the international community has partnered with the people of Afghanistan to raise literacy levels and encourage education for all. It is an uphill struggle — one undertaken at times with enthusiasm and at times with suspicion. In addition to regular schools, literacy classes have been introduced into non-traditional spaces to make them as accessible and acceptable as possible.

A small house in a rundown area of Kabul is a gathering point for widows and their daughters. The women have all experienced trauma brought on by the war and related violence. After receiving counseling for a few months, they take part in literacy classes. Each step forward gives them more power over their own lives.

The women crowd into a low-ceilinged room with walls decorated with the handicrafts they have made. They sit on toshaks along the walls, and when those are filled, they move into any available space on the floor. A small woodstove takes the chill out of the winter air.

Faranoz comes here with her mother. She has seven sisters and three brothers.

Everyone says I have too much intelligence. They laugh when they say it, so it is a joke, but they are right. I am very smart.

A year ago, I could not read anything at all, but now I can read all sorts of things — books, poems, everything. I can write, too. This proves I am smart.

I live in a poor area of Kabul. My father died thirteen years ago. No one in this room has a father or husband. The men died in the war or from sickness or they were murdered. Husbands and fathers die for all sorts of reasons. Some get shot. Sometimes there are road accidents. Some fathers go to Iran or to Pakistan to look for work and don’t come back.

My mother has no job, so we are very poor. My oldest brother is in charge of us. He is the one who said I should not go to school, so that is why I spent so many years not knowing how to read. I don’t know why he said no school for me. Does he have to give a reason? Maybe he doesn’t think I am smart enough for school. Maybe he is afraid I would end up smarter than him, and then how would he be able to tell me what to do? The women in this class have all been through bad times in the war. I was very small when the war ended but I hear everyone talk about it.

Our lessons are supposed to last one and a half hours, but they often go longer because the women want to talk about their problems. But that was more in the beginning. As they become better at reading they want to talk more about reading and less about the things that make them sad.

This meeting room is really just a room in a woman’s house. The woman used to be married to a man who belonged to the Taliban. He was a very bad man. He beat her and made her be with other men, a very disrespectful thing. But she was very brave. She went to the Supreme Court and got a divorce. I don’t know when this was. Sometime after the war. This is her brother’s house. She lives here and he lets her have this room for us to meet.

Our teacher is a lawyer as well as a teacher. She has told us about how she defended women who were being beaten or treated badly. She says important people have offered her important jobs, but she prefers to be here in this room with us, because we are important, too.

The first day of classes, many women were crying because their lives are so hard and no one ever asks them about that. They don’t get to just come and sit and talk with other women. They are expected to just live their lives and be quiet. But the teacher here started to ask them and that’s when they started to cry. Some would not talk at all at first. Even I was too afraid to shake the teacher’s hand or even to look at her. I was afraid that she would see that I was not smart. But now I know I am smart, so I am not afraid anymore.

After a year of learning to read, we are all different people. We can stand up straight and read out the words we have written in loud clear voices. We laugh more than we cry.

Even though I am young, I know many things. Sometimes the older women forget I’m in the room, and they talk as if I’m not here. I hear all about their lives, about their children who died or their husbands who hit them.

I know that some women did not tell their families they were coming here. They said they were going to the market or to a clinic, or they only came to class when no one was at home to stop them. Only after many months had passed did they tell them, and by then they could read some things, so their families said, “You are using your time well, you are learning something, you are happier, okay, you can continue to go.”

The courtyard of a home where literacy classes are held.

The books we most like to read are about law, the constitution and about religion. Through these books we learn that we have rights. And if our families disagree, we can point to the book and say, “Here! It is written down! The law must be respected!” Religion does not give men the right to beat us, and now we can prove it.

Some of the stories are funny now, because we know better, but they weren’t funny when they happened. One woman says she got a prescription from the doctor and she got it mixed up with other papers, and what she took to the pharmacy was not the prescription, it was the electric bill! Women talk about how they used to be like blind, but reading has made them able to see.

I used to think, if only I could read, then I would be happy. But now I just want more! I want to read about poets and Afghan history and science and about places outside Afghanistan. Many of us write our own stories, and we decorate the borders of the pages with drawings of flowers and designs, because that is the Afghan tradition.

My brother lets me come here because it’s not really a school. More just a place where women get together to learn. My mother was the first to come, and when he saw that she felt better and seemed happier, he said, okay, it would not be bad if I came with her. There are only women here, so he thinks I won’t get into trouble and make him look bad.

I hope he lets me go to a proper school one day because I like to be around books and I would like to be a doctor one day. I think I would be a good doctor. What else can I do with so much intelligence!

Liza, 16

A tradition of Islamic art — or art created in the Islamic world, regardless of the religion of the creator — involves creating a sense of balance and harmony. One part of the tradition is to focus on patterns rather than representations of living creatures. The magnificent tile work on mosques and public spaces throughout the Middle East is a testament to the grandeur of this style of work.

Other traditions, such as the one led by the great Afghan miniaturist of the sixteenth century, Kamal al-Din Bihzad, created spectacular illuminated books of illustrated poetry and legends, with people and even the Prophet Muhammad represented in full-face drawings.

The first national Afghan school of fine arts was established in 1921, with other schools coming along as the decades passed and leaders changed. When the Taliban took power, art was one of the many forms of self-expression they crushed. They even destroyed many of Afghanistan’s artistic and cultural treasures, such as the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan (magnificent giant statues carved into the side of a cliff and deliberately dynamited by the Taliban in 2001). Most forms of art were against the law.

In one of the many attempts to rescue and rebuild the cultural life of Afghanistan, a women’s art center was established by the Centre for Contemporary Arts Afghanistan (CCAA). Since 2006 it has trained hundreds of young Afghan women in painting, photography and filmmaking. After living in a time when their voices were silenced, having ability in the arts allows women and girls like Liza to express themselves in new and daring ways.

I live with my mother and one sister. My father died from an untreated illness some time ago. When he got ill, there was no doctor and no medicine. We could see he was sick and suffering, and we did what we could to try to keep him warm and comfortable, but the pain was bad and we watched him die. We were all helpless.

To lose a father in Afghanistan is a dangerous thing because it is very hard for a woman to earn enough money on her own to support herself and her children. She has to rely on someone to help her — an uncle, a brother — and that makes her like a beggar.

For my family it has been very hard. I was seven when my father died. He used to work in a shop selling carpets. I remember visiting him there to take him some lunch. It was the time of the Taliban, so my mother could not go outside with any safety. The Taliban would beat her if they saw her. It was a little safer for me because I was a little child, and they usually ignored very little children. The shop was near to where we lived and I would run there and back. I ran because I was afraid of them. But I was glad to get out.

Except for taking the lunch, we just sat inside. No school, no playing. Nothing. The days were long and we would argue just for something to do. When you are locked up with someone, everything they do can quickly become annoying, because you can’t get away from it. Every day is the same.

Before the Taliban fell there was a lot of fighting and shooting. It was terrible. But then it stopped and things are better now. I am about to start grade ten. I study very hard in school. We are on school break now for the winter. Instead of going to regular school classes I come here every day to work on learning art.

After the Taliban, my family was really hopeful. People would come to visit and I’d hear them talk. “The dark period is over,” they’d say. “We can all breathe again.” But it’s not really like that. We can do some things, but we never know who is watching and who will try to stop us with violence or by saying bad things. I try not to think about it. I prefer to think about art.

A sculpture in the courtyard of the women’s art center.

I am just beginning to learn about it. I’ve been learning about colors and shapes and how to use light and shadow. When I look around at some of the work done by women who have studied for a while, I think, “How can they do that?” Then I think that one day a new student will ask the same thing about my work, because I will be so good at it.

Many girls paint their memories or their thoughts about their memories. How do they feel when they remember this thing? That’s what they paint. So when you see their painting, you get their feeling.

The older artists paint sadder, darker pictures than the younger artists like me. Of course, we are still learning technique and have a long way to go in our studies, but I think we are looking more to the future than to the past. I have heard many sad stories, and I know there are many more, too many more. I want to think about happier things and put my mind and my art to making work that will give people a good feeling instead of a dark feeling. We all have things inside us that need to come out. It can be dangerous to speak, or maybe you are too shy to speak. But you can draw your feelings, in private, and let them out.

We have all lost things because of the war. Losing things and people is normal for Afghans. We have had enough of that. It is time to plan for good days and before you can do that, you have to fill your head with thoughts that are hopeful.

That is why I like to paint the ocean. I have never seen the ocean for real. One day I will, when I travel the world as a famous artist. I paint it because when you look at the ocean, nothing gets in your way. There are no obstacles. You can see forever.

This is what we want for Afghanistan — no more obstacles!

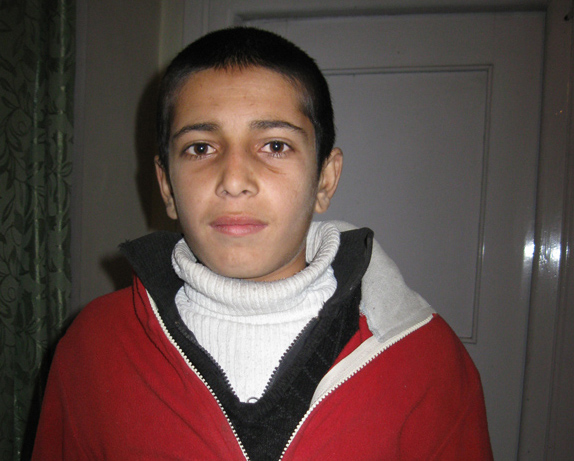

Aman, 16

Poverty and child labor go together. War creates poverty. War creates situations where families are so desperate for food and shelter that children must work to provide these necessities, especially if their parents have been killed or maimed by the conflict. War also destroys schools, and when schools are destroyed, opportunities for a way out of bone-grinding poverty are destroyed.

In Afghanistan, children are engaged in all sorts of work, from water-carrying to sheep-herding to carpet-weaving and working in shops. The money they earn goes to basic necessities like bread, and a hard day’s work nets them barely enough to keep starvation at bay. And if they don’t work, they don’t eat.

Aman is one of the lucky ones. He landed at a school that educates child workers and others from very poor families. The school is down a chopped-up, muddy alley in a slum district of the city. It is surrounded by high walls. It looks shabby compared to schools in North America, but inside it is a safe haven, a powerhouse of young minds reaching for something better.

I lost fifteen members of my family to the Taliban, including my parents. We were living in Kabul. Not in a rich neighborhood. Lots of poor families. The Taliban came and said to my father, “What is your name?” He told them and then they killed him. Then they killed my mother. Then they kept on killing until fifteen members of my family were dead. I am alive and my little sister and my grandfather are alive. My grandfather is disabled and lives a very poor life. So I live here at this school with my sister.

I am now in grade nine and I am at the top of my class. I want to be a doctor, of course. This is the dream of many Afghans because we have seen so much death and suffering.

I did not begin school at the correct time in my life because I had to work. When I was young I was a shepherd and looked after sheep that belonged to someone else. My job was to keep the sheep together in the street and take them from one garbage dump to another so they could rub their noses through the plastic bags and things people threw away. That was how they would eat. They had to eat garbage because we have no grass in Kabul except in the parks and they were far away from where I lived and they don’t allow sheep. Everything else is dust and rock.

A computer room at a school for impoverished and working children.

It isn’t a hard job, looking after sheep, but I was very small at the time. It seemed hard to me then. The sheep were bigger than me! I was always afraid they would not go where I told them to go. If I lost one, it would have gone very bad. It doesn’t matter whether I liked it or not. It was my job and I had to do it.

If I wasn’t able to go to school that might still be my life, taking sheep from one garbage place to another. So I study hard and I work hard. I have no free time. Every hour is busy.

I help teach the younger boys here. Most of them also have jobs. This one is a mechanic, this one goes through garbage, this one helps out in a shop. They work in the morning. Then they come here for a free lunch and stay for classes. Many of the boys here earn money to support their whole families, so they have to work. If they don’t work, no one eats. The free meal they get here at the school for lunch makes their family feel better about them spending the afternoon at classes instead of at more work.

When I miss my family, so much that my chest hurts and everything hurts, I try to calm myself by thinking of my future, because I think it could be a good future if no one comes in and starts killing again. Look at what I’ve learned in just a few years! When I first came here I was afraid all the time. I had too many dark, sad things in my head. I thought there would never be room there for anything else. Then I learned how to read and write and even to use a computer. So now I have many good things to think about.

I don’t know why the Taliban killed my family. My family were innocent. They were not important, fancy people. They were nobody’s enemies. The Taliban killed my family just to show their power. They did a lot of that, killing whole families. You can see it when you go into a graveyard. Big groups of family members all buried on the same day. Like they are on a picnic. Only they are dead.

Karima, 14

Women need economic power. Economic power means having ownership over enough money to create their own lives, to live without being dependent on men for food, shelter and the other necessities of life. This is true for women everywhere.

In North America there are laws to protect the rights of women and, just as important, there are strong social customs to back those laws up. When Canadian and American women are beaten by their male partners, there are shelters for them to go to with their children, and the police can arrest the men for assault. The system doesn’t always work the way it is supposed to, and each year women are still murdered by their male partners. But the ideal we strive for is that no one has the right to make anyone else live in a state of fear. And since women in North America have the right to earn their own money — and decide how to spend it — they can learn to make the types of choices that will help them avoid or get away from abusive men.

In Afghanistan social customs make it very difficult for women to have independent economic power, and without that, they must depend on men for their survival. Very often this turns out fine, as the vast majority of Afghan men — like men anywhere — are kind and strive to do the right thing. But when a woman is forced to be dependent on an abusive man, her choices are often limited. She can suffer through it and hope things get better, she can commit suicide, she can escape the home and hope she is not found and killed for “dishonoring” her family, or she can kill the abuser and be executed or spend the rest of her life in prison.

Karima and her mother face this situation every day of their lives.

My father has been dead for ten years. He died of a brain attack. My mother washes clothes for people in the neighborhood, and they give her a little money. It is not enough to live on. We live in a poor area and the neighbors can’t pay a lot.

I have three sisters and one brother. My brother is seven and the youngest. We live with my mother’s brother, my uncle. He has just a small house — one room we share with his family. There are too many of us in that small space, but where else can we go?

There are not enough mats for us all to sleep on, so my family sleeps on the floor. There is a rug but it is thin, and the floor is a cold and hard place to sleep. The house has no electricity. None of the houses in the area do. When it becomes dark outside it becomes dark inside. I have no way to do my homework.

My uncle has oil lamps and candles, but when I try to use one to study he says, “Why are you sitting there with books? Why do you just sit while I have to work to feed you? You should not be going to school. Your job is to get a husband, not to sit around with books, using up the candles.”

I am lucky, though, because my mother stands up to him on this matter. She tells me to go to school, to study hard and make a good future for us.

My mother never had the chance to go to school. She cannot read or write. She has no experience of these things. But she knows how hard her life is, and she thinks that education might be the way to an easier life.

My great ambition is to one day work in a bank. It is a job that a woman can do where she will have good responsibility and where people will treat her with respect.

I cry sometimes because my uncle is very cruel to my mother and brother and me. He hits us. He says insulting things to us because he does not want to have us around, but we have nowhere else to go. When I get my job at the bank I will make a good salary and take us all to live in another place, far away from my uncle. But that is still many years from now.

We don’t know what will make him angry. If we did, then we wouldn’t do it. I think he is just angry when we breathe, and we can’t do anything about that. My brother is a boy and can run outside, but my sisters and I can’t just leave the house when we want to. It’s not safe for us outside, either.

My uncle keeps threatening to find me a husband. I know that will be my fate, that one day he will marry me off to someone and I won’t be able to disobey. But I hope I get to live part of my life for myself.

So I come to school a lot because school is a nicer place than home. After I finish regular classes I stay at school for special courses, like English, tailoring and computers. All classes are free at my school, as long as you do your work. You cannot just come and not work because someone else would make better use of your space.

When I do go home I spend most of my time taking care of my little brother and helping my mother wash clothes. My favorite food is spaghetti. Sometimes we have it here at school for lunch. I have one good friend, a girl in my class. She has a hard life, similar to mine, so we understand each other very well.

We both work hard in school. We hope one day to have a life.

Sharifa, 14

One of the legacies of decades-long war in Afghanistan has been the bombing, land-mining and burning of orchards and farmlands. Afghanistan used to grow enough food to feed itself. War changed that.

Farmers came back from war or exile to find that their land could not be used. But they still had families to feed. So they turned to a crop that can grow in rocky, dry soil — opium poppies.

Opium poppies produce a gummy substance that is the raw material for heroin, an illegal, addictive drug. The opium itself can be smoked. It is a painkiller, producing a heavy stoned feeling in those who smoke it.

Afghanistan now produces more than 90 percent of the world’s heroin. It is used by addicts in Russia, Europe and North America. The trade is controlled by warlords and other criminals — and the Taliban — who have no interest in human rights or the well-being of children. The money they get from selling heroin buys them more guns and more power.

The poppy farmers are generally poor families growing poppies on small plots of land that will not support any other crops. They often have to borrow money to buy the seed. If their poppy crop is destroyed by foreign troops to prevent the heroin from being sold in their home countries, the farmers cannot repay the debt. So they may give in payment the only thing they have — a daughter. These girls who are forced into marriage — a form of rape and slavery — are called Opium Brides. Farmers who don’t pay their debt have also been tortured and killed.

Heroin is a bad business.

In the absence of proper medicine, opium is used to get rid of pain, including the pain of hunger. Parents give it to babies who have earaches and to children whose bellies are empty. For adults, smoking opium eases the pain of long hours of back-breaking work, and it blocks out the memories of trauma from the war.

The number of opium addicts in Afghanistan is estimated at 1.5 million. In a country of thirty million people, that works out to one of the highest rates of addiction of any country in the world. Treatment options are very few.

Anyone who has lived with or known an addict knows the kind of chaos and havoc they create around them.

Sharifa has an addicted father.

My brother is one year younger than me. We live with our mother. I hear from other girls how their family members sometimes argue, but we don’t have that problem. The three of us have to pull together if we are to manage, and even then it is very hard. So we have no energy to waste in arguments. What would be the point? Our lives would still be hard, no matter who won the argument.

My mother washes clothes for neighbors and also does cooking jobs when she can, not as a formal cook but as a helper. My brother does odd jobs to help out, whatever he can, carrying things or helping someone out in their shops. He gets paid very little. He works hard, but people think he is young so they don’t need to pay him much.

I wish there was a job I could do to earn money, but for Afghan girls it is very difficult.

My father is still alive, I think, but he does not live with us. As far as I know, he is in Karachi staying with relatives, but I can’t be sure.

He is addicted to opium. He has been addicted for ten years. He used to be a shopkeeper. He kept up this job even while he was addicted, but then his health became too bad. He took more and more opium and he stopped working.

It was hard to live with him. Our house always smelled of opium smoke. My clothes, too, would hold the smell. When I went to school other children would call me names because of the smell on my clothes. I tried to keep clean but there was no place to hang clothes away from the smoke.

My father had many moods when he lived with us, all bad except when he had smoked a lot of opium. Then he just lay on the floor and didn’t bother us. He had a lot of bad memories from the war, my mother said, and was in pain a lot of the time from injuries that had no proper treatment. Opium took away his pain and his memories.

When he didn’t have opium, he would smoke hashish. When he could not get these things, then he would be in a very bad mood. He would yell and say bad things for hours and hours, mean and insulting things. We all lived in one room and there was no way to get away from the insulting things he said. And there was no way to make him feel better.

Finally, it got so bad my mother asked his relatives in Pakistan to take him in. I don’t know how she came up with the money or how she got him to go. But he went away and now it is just the three of us.

I try to remember that my house is not me. Where we live it is very, very bad. We have no clean sheets, no beds. We sleep on the floor. We try to keep it clean but there is mud when it rains and dust when there is no rain.

We have no electricity, just a little oil lamp that we light to do our homework, but we must work quickly and not waste the oil.

I like to have fun, and at school that can happen sometimes with my friends and classmates. We all work hard, but we can’t be serious all the time! We are not old yet!

I have decided not to be married. I want to be a doctor, and I don’t want a husband that I have to take care of. I want to do good work and make a better life for me and my family.

Sadaf, 12

One of the great Islamic traditions is the discipline of memorizing the entire Qur’an, the Islamic holy book. This tradition may spring from the days when books and literacy were less widespread than they are now. Memorizing and reciting the Qur’an was a way to pass on the words from one person to another.

A person who has accomplished this phenomenal task is called a hafiz. It is a revered title, one worthy of respect. The Qur’an is more than 86,000 words long, and it takes, on average, three to four years to memorize the whole thing. Anyone who has tried to memorize a poem for school will understand the concentration and dedication such a task takes! The children who accomplish this are said to be an extra special blessing to their parents.

Becoming a hafiz is a goal of Sadaf’s.

I live with my mother and three sisters. My father was killed in a rocket attack a few years ago.

We were in our village, which has the name of Kolach. It was an ordinary place, not a special place.

My father liked to pray outside. He liked being under the sky instead of under a roof. So he was outside of the house, kneeling on his prayer mat, saying his prayers. And a rocket came down and killed him.

The rocket blew my whole house apart. There was nothing left of it. Maybe scraps of things. Nothing we could use. Nothing of value.

I was in my grandfather’s house at the time, with my mother and sisters. My grandfather’s house was right beside my house, so when the rocket hit my house, we felt it at Grandfather’s.

It was very, very bad, so bad that you cannot even imagine it, like a nightmare. But worse than a nightmare. When you are next to a rocket exploding, you see it, you feel the ground shake, you hear the noise like a big animal roaring, and you smell it, too, the fire, the dust.

I did not want to believe that my father had been killed. I wanted to dig through the yard, through everything that was broken, to see if we could find him. But my grandfather took me away. It would not have helped. Of course he was dead.

I don’t know who fired the rocket. Maybe it was the Taliban. Maybe it was the foreign soldiers. You think they would tell me? You think the Taliban would come to me and say, “Oh, we killed your father but we didn’t mean to. The rocket went the wrong way.” No, they don’t do that. Nobody explains anything.

My father was a good man, a kind man. He liked his daughters to be smart and to learn things. He was proud when we learned how to read.

After the explosion my uncle took us away to another village to live with him. He is my mother’s brother. We lived with him for a few years. My grandfather was too poor for us to stay with him. Now we are here in Kabul, trying to make a new life.

My two older sisters are married now, and they share everything with my mother and me. When they get some food, we get some food. My mother is jobless. She gets a bit of money from her brother, but not a lot. He is a laborer and does not make a lot of money.

The thing I most like to do is study the Qur’an. My father was killed while he was praying, and I think that makes his death holy in some way. I like to think so, anyway. By studying the Qur’an I feel that he is not so far away from me.

It is my dream to one day memorize all of the Qur’an. It was the wish of my father that all his girls be able to do this. I want to become a hafiz, which is what people will call me when I have memorized the whole Book of Allah.

It will be a big job. The Qur’an has 114 surahs [chapters] and over six thousand verses. But others have done it and I will be able to do it. Then the message of the Prophet will be inside me, and I’ll always have it, even if all the Qur’ans disappear. And when I have a problem, I can know what part of the Holy Qur’an will help me solve it.

I haven’t started to memorize it yet. I am still learning to read it, and I make a lot of mistakes. When I stop making mistakes, then I will start to memorize.

There is a television show on Afghan TV called Qur’an Star, for those who memorize the Qur’an, a kind of competition. I want to go on this program and do well. That is one good way I can help my family. The last winner was a sixteen-year-old girl. She won 150,000 afghanis ($3,000 US). My family will be helped a lot with that much money.

My mother says that when it is her turn to die, it will be my responsibility to recite the prayers over her body. She says that praying over her will be more important than crying over her, so I should practice the prayers and have them easy in my mind to get to when the time comes.

I hear that Kabul is a nice city, with parks and gardens and big shops and even a zoo, but I haven’t seen any of that. All I have seen is this area, and it isn’t very nice. It doesn’t really matter, though, if you live in an ugly place. If you have beautiful thoughts in your head then it’s like you are living in beauty.

In the future I want to be a teacher and teach both English and Islamic studies. People who know English are more respected, and if I am a scholar of Islamic studies, I can help spread the news of the Qur’an.

War comes when there is no unity, when people look out for themselves instead of each other. But through discussion we can solve all our problems, create unity and avoid war.

Mustala, 13

Life expectancy for people in Afghanistan is, on average, forty-four years. In Canada and the United States it is about eighty. Poor nutrition, lack of access to health care and clean water, exposure to the elements, poverty-related illnesses such as tuberculosis, plus war and related violence all take their toll. Twenty percent of all children born in Afghanistan die before they reach their fifth birthday.

Many people have fled Afghanistan because of the war. Others have left in search of jobs or a better life elsewhere.

In Canada and the United States, we have an economic safety net. People over sixty-five receive a pension. People who are out of work are often eligible for unemployment insurance. For those who are too ill to work, there is another type of assistance. We have these things because the people who came before us worked really hard to make them happen. We have also never suffered the horrible destruction of prolonged war on our land.

War creates poverty. In countries like Afghanistan, where there has been prolonged war, there is no economic safety net. People go hungry. According to UNICEF, nearly 40 percent of children under the age of five are undernourished, and over half of all children under five are smaller than they would be if they had enough to eat.

Mustala’s family has been split apart by war.

I live with my grandfather and grandmother. We are really poor. My grandparents don’t work. We have no money for soap, so I am often dirty and wearing dirty clothes. I would like to be better dressed, so when people see me coming they will think, “Oh, this boy is important, look at his clothes. He must be somebody special.” No one will think that of me if I don’t have nice clothes.

My father left when I was quite small. He went to Iran to find work and also because some people here wanted to kill him. My mother got another husband and left us so she could be with him. I think she has other children now.

Classrooms and playground at Mustala’s school.

I get free food at school, which is often the only time I eat, and sometimes my grandparents don’t eat at all. When I can, I put food in my pockets at lunchtime to take back to my grandparents, but it is a thing that makes me nervous to do. I don’t want to get in trouble. So, sometimes if I am hungry for two pieces of nan, I take two, but I don’t eat them. I hide them in my jacket to take home. That’s not stealing, is it?

This whole school is filled with kids who have a hard life but who are really smart, although not all are as smart as me or as good at playing football as me! Many have lost one parent or two parents in the war or from some illness. I have not lost my parents. They are both alive. They are just not with me.

I wish my father would come back from Iran, even for a day. He would see what a smart, good boy I’ve become, and he would keep me with him. I don’t care where. I could go back to Iran with him or we could stay here. Or we could go someplace else. I would be fine with any decision.

Sometimes my mother sends my grandparents a little bit of money to help out. This way I know she hasn’t forgotten about me. Her new husband would not want me to live with him, so I don’t think about that or dream about that. When I get to be a man, maybe I can take care of my mother and she won’t have to live with him anymore. But that’s a long way off.

I was young when my father left, maybe five or six. Sometimes, when I’m playing football with my friends, a man will stop and watch us or will walk by really slowly, and I think, “Maybe that’s my father.” I play extra well then, so that he’ll take me away with him. He won’t want a son who is no good at football.

It gets very dark in our house at night, and sometimes I get afraid. When you hear things in the dark and you can’t see what they are, anybody would be afraid. It doesn’t mean I’m not brave. But if someone shoots a gun or there is yelling or a cat screams, it can get scary. When I get scared I try to think of football or I practice my English.

I think Afghanistan could be a great country, especially if I was the president. I’d help all the poor people and make sure they have food and electric light. I would make a law that everybody has to go to school. Even adults, because there are a lot of adults who have never been to school, and I think that makes them have bad tempers. If they see me going to school, they yell at me that I should be working. So I would make them to go school, too, so that they’d stop bothering me.

We need to study to make a good country out of Afghanistan. Right now we are a backwater country. At school I have learned there are better ways to do things than all this war, war, war all the time. It’s the young generation that will change that.

My generation.

Me.

Ajmal, 11

In the western part of Kabul is a holiday spot called Qargha Lake. It has guesthouses that are rented by Kabul’s elite during the summer, a beach with donkey rides for kids, a picnic area, a restaurant and even an old amusement park. Nearby is the golf course that was built by King Habibullah in 1911, occupied by Soviet tanks during the 1980s, and then planted with land mines by the Taliban. When the Taliban left, it became a place where people were trained in how to remove land mines, and now golf is played there again.

Ajmal and his younger sister, Spegmai, try to get money from Qargha’s few visitors on a cold winter day.

My sister is ten. We live in a neighborhood a little ways from here. It takes us a while to walk here. I don’t know how long. I don’t carry a clock. A while.

Both my sister and I go to school, but we don’t go every day. Sometimes the school is closed. Sometimes it is open and we go but the teacher doesn’t show up, so we leave again. Sometimes there is no food or money in our house so we have to go out to work instead of going to school.

Our mother is dead. I don’t know how she died. She was sick, I think, and we had no medicine. So she died.

Our father is also sick, but he is not dead. His sickness is in his legs. When he is feeling well he looks through garbage to find something we can eat or use. He taught us how to do that, and so we do it when we are out.

You have to pay attention. You can’t just go walk and think of other things. You have to see everything and think about if what you see is useful. I found a plastic bag on the beach this morning and put it in my pocket. A plastic bag is useful.

Today it is cold and the lake is frozen. Not many people are here, so we don’t make much money. When there are a lot of cars we stand in the street and bang on their windows.

Our work is to ask people for money, and when they give us money we burn some coal and the smoke takes away the evil spirits. We make maybe 35 afghanis a day (about 75 cents) when people are kind.

Qargha Lake holiday spot.

My sister likes this work more than I do. She is better at running than me, and she is pretty and speaks well, so people are nicer to her.

I do not run well. My legs have a kind of sickness like my father’s, and you can see I do not speak well. So people laugh at me and call me names.

If people don’t want to give us money, that’s okay. They don’t have to. We are small. What can we do to them if they don’t give? But why do they have to be mean? Why do they have to call us dogs and say bad words? That’s what I do not like about this job.

My sister likes writing the best in school and I like reading the best. I would like to become something in the future. I don’t know what, just somebody of importance. Maybe I’ll become a teacher. When I’m a teacher I will show up for work every day so my students don’t waste time sitting in an empty classroom with nothing to learn.

Amullah, 15

Cricket was made popular by Afghans who had spent time as refugees in Pakistan, where cricket is played and followed with great enthusiasm.

When the Taliban came to power in 1996, they banned the game. They allowed Afghanistan’s national cricket team to play again in 2000, but spectators were not allowed to cheer or clap. All they could do to show their enthusiasm was say “Allahu Akbar,” which means God Is Great. And the games had to be scheduled around the executions and torture that the Taliban carried out in that same stadium.

Amullah and his friends are taking advantage of a free day to work on their cricket game in the schoolyard.

My father is a farmer, or he used to be. We had to leave our land when I was small because of the war. There was shooting, bombing, people being killed for no reason. I don’t remember much about that time because I was very small, but my older brothers have told me. It got so bad that we couldn’t stay there. We moved around a lot, from place to place, trying to find somewhere safe. We ended up in Kabul.

My father now works as a shopkeeper in someone else’s shop.

I don’t remember much about the Taliban time. Like I said, I was really small. My brothers said that for them, the worst thing was that they couldn’t play sports. The Taliban wouldn’t let them. They wouldn’t let anybody play. But people would listen to games from India and Pakistan on radios they kept secret.

How could they say, “No more football, no more cricket”? Those are the best things in life! It’s a good thing I was small. If they came back into the government with those rules, I would go mad. I remember my brothers trying to play football and cricket in our house, but we had a very small house, and our mother did not like them playing ball inside.

My school is on holiday today, but we all came here to practice because we have a big cricket match coming up soon against another school, and of course we want to win!

Cricket practice at Amullah’s school.

All of us, yes, we like to play, but we also want to do good things for Afghanistan, like be teachers, doctors, engineers — all of the best kind because there is so much to do.

I want to finish my schooling here, then go on to study agriculture. My father talks about his little farm, how much he loved it, and I would like to get that back for him. Probably not the same farm. That’s all gone in the war, but another piece of land, a better piece. Then I would take him and my mother out of Kabul to a place that is cleaner and quieter, and they can have some peace.

I think it is good to study agriculture because there are new ways of doing everything. All the time, people are coming up with new ideas. Some may not be good, but some may be very good. So I’ll learn all I can, then become a good farmer. Maybe even a rich one!

But first we need better security. Everyone is tired of being afraid. Here in the schoolyard everyone is playing hard and we’re having fun, but we can never really forget about the security. We see helicopters every day and military cars and trucks, and things still get blown up.

But if all that can stop, then Afghanistan will be great, because there are so many of us who want it to be great, it can’t be anything else.

Shabona, 14

Years of war and repression have left Afghanistan lacking many basic things that other countries take for granted. A country without a fully functioning education system, for instance, cannot hope to move forward. After the fall of the Taliban, Afghanistan needed everything — school buildings, books, chalk, pens and teachers. Trained teachers were in short supply. The Soviets, the warlords during the civil war and the Taliban all targeted teachers because teachers have such power to encourage independent thought — and independent thought is the enemy of despots.

Teacher training is a priority for many organizations working to help rebuild Afghanistan — especially training women, since many families don’t want their daughters to be taught by male teachers.

At a large wedding hall in Kabul, teachers from all over the area have gathered to learn new teaching methods from each other. Shabona and her classmates are taking part.

We are from a high school about an hour from the city of Kabul. We have come here today to sing for the teachers who are part of this teacher-training conference. We sang the Afghan national anthem this morning and we’ll sing something else this afternoon.

I like the national anthem. It lists all the tribes in Afghanistan, and it’s about how everyone should work together, even though they don’t.

Then we had to sit and listen to the teachers. Some of them talked too much, but some were interesting.

Some teachers sat up front in rows and pretended to be students while other teachers took turns pretending to teach math or science and other subjects in new ways to make it a better experience for the students. Some of their ideas would work better than others, in my opinion. I think it’s better to have a conversation with your students, not just talk all the time, because that can make us drift off, especially if we’re hungry.

Our school is a good school, but there is no safe place for us to run around outside. We are girls but we want to move, too! It would be nice to have some green space that is safe so we could run around without being stared at or yelled at.

I like most to study science. At my school we can study geometry, math, chemistry and biology. It’s all from books and sheets of paper and notes on the blackboard. We have two microscopes but they are very old and broken.

There are so many girls who want to come to our school. We have almost 2,500 girls! We have to go to school in shifts. I’m on the morning shift. I’d like to go to school all day but we have to make room for the others.

I was really young when the Taliban were in power, so I don’t remember a whole lot. Our teacher remembers. Whenever she thinks we are not studying hard enough, she tells us about that time. She had to leave school and was stuck at home most of the time. Her aunt had a little school for girls in her home. Not a school, just a study group, really, but it had to be very secret. Our teacher would put her schoolbooks in a basket, then cover them up with fruit so the Taliban wouldn’t find out that she was studying.

The Taliban were ignorant. They didn’t know that men and women are equals. It says so in the Qur’an.

The Taliban broke their own rules all the time, too. Our teacher’s brother was arrested by them three times. He had a little shop, a secret shop that sold satellite dishes for televisions. These were against the law, so the Taliban would arrest him. But then they would say, “You can go free if you give me a satellite dish.”

Our teacher says it was hard for her to go back to school after the Taliban because her brain wasn’t used to working. She says if studying hard becomes a habit with us, then we’ll be able to continue the habit if we are ever forced out of school again.

We joke around, but we are also serious students. We want to be doctors or journalists or members of parliament or teachers. We will have to get there through hard work because none of our families have money. Just in this group we have girls whose fathers died in the war, who have had family members injured or homes that were blown up.

I was living in an area south of Kabul. There was a lot of war there, even after the Taliban were kicked out of power. We had lots of rockets, lots of shooting, lots of explosions. It was very scary. I remember not wanting to leave my mother’s side. She would even just go into the next room and I’d scream because I was afraid I would never see her again.

We were about to go to Kabul where it was supposed to be safer. Really, we were ready to go, about to get into the car, when a rocket hit the car and it exploded. So we were stuck until we could find another car to take us.

For fun, my friends and I try on each other’s makeup and try out each other’s cellphones. We would really like a place to exercise and play sports, but we have nothing like that. We do it in a small way, inside, but it would be great to be able to just run and run and run.

Will there be another war? We hope not! Afghanistan has had too much war. If war has to happen, let it happen somewhere else. Do you have war in Canada? Maybe it is your turn, then.

Abdul, 14, and Noorina, 15

Scouting has a long tradition in Afghanistan, as it does in many countries. In 1978 it was banned by the Communists, who wanted to set up their own youth organizations. It stayed banned during the civil war and the Taliban regime. In 2003 it was started up again with the help of international donors, and now it is sponsored by the ministry of education. Afghan Scouts perform a variety of public services, from cleaning mosques to assisting firefighters.

Abdul and Noorina are very proud of what they are accomplishing in their Scout troop.

Abdul — Everyone in this Scout troop has lost at least one parent. We have come from many different provinces — Laghman, Kandahar, Daikundi, Lowgar, Badakhshan — all over. We live in a special place called Maristoon on the edge of Kabul.

Maristoon means community in Dari. The people who live here all have some special struggles. They are orphans or they are disabled, and everyone is very poor. But even with all that, we can do many things.

My own father is dead. My mother is blind. I’m not sure how she became blind. I think it was in the war. The war killed my father. My mother won’t tell me much about it.

Noorina — My father used to work at the Afghan Embassy in Moscow, under a different time. Our whole life has been back and forth from war to war. When things were dangerous for us in Afghanistan, we went to Quetta in Pakistan and lived in a refugee camp. Then when Karzai became president, my father thought Afghanistan would be safe so we went home. But it was not good. It was still dangerous. So we went back to Pakistan.

My father set up a little shop in Pakistan. Just a little place selling groceries and little things. One day he went out to the shop very early, without even having breakfast. So my mother and I decided to take him breakfast. We got some food together but when we got to the shop, there was no shop! A rocket had hit it. The whole thing blew up. But my father wasn’t killed in the explosion. Someone shot him. So maybe he got out of the shop when he heard the rocket coming and thought, “Oh, good, I’m safe.” Then someone came along and shot him. I don’t know if that’s how it happened or not. I just imagine it like that.

It wasn’t safe for us in Pakistan. So we came back to Afghanistan. I hope it will be safe this time.

Abdul — We all have stories like that. Nazifa’s father was kidnapped by the Taliban and then killed three days later. Naramullah’s father was shot. Aziz lost both of his parents in the war. He lived with his uncle, a doctor who treated people in the refugee camps around Kandahar. His uncle died of a heart attack. Lots of stories. It’s normal for us.

We belong to Scouts because it is a way to improve ourselves and improve our community. It is part of the Scout promise:

On my honor I promise to Allah that I will do my best

To do my duty to Allah, and my country Afghanistan

To help other people at all times

And to obey the Scout law.

We learn a lot in Scouts. Seeking knowledge is our whole mission. We learn how to respect elders, how to keep the environment clean, how to prevent fires. We live in a green area — well, it will be green when the spring comes. We learn how to take care of trees and land. Afghanistan has been through a lot. A lot of the country has been destroyed, but we can make it beautiful again.

I have both good and bad memories of the Taliban. Mostly they were very bad, but sometimes they would bring food to families who needed it. They helped my family in this way, so this is a good memory.

We see a lot of foreign troops. Scouting is a normal thing in many parts of the world. It was started by a British man in 1907. When the foreign troops hear about our Scout troop they want to come and visit us. Just last week some foreign soldiers came and took us on a hike into the hills behind Maristoon. That was a good day although not for our Scout leader. She had a hard time keeping up!

There are boys and girls together in this Scout troop. Men and women will have to work together to rebuild the country, so we learn here to be leaders. Good leaders. Leaders that people will trust. Afghanistan needs that.

Fareeba, 12

In wealthy countries, people with mental illness have a rough time, even when they are supported with resources, pensions, medication and therapy. In poor countries, people with mental illness are often at the bottom of the pile.

War creates trauma, and trauma can lead to mental illness. In 2010, the Afghan government estimated that two-thirds of the Afghan people suffer from psychological problems such as depression, severe anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Treatment options are limited, with fewer than fifty psychologists and psychiatrists in the whole country.

Without good medical alternatives, people sometimes turn to tradition and superstition. These include dropping off their loved one at a shrine. There, patients are suspected of being possessed by demons, or djinns. The patients are fed only bread and water and are kept in chains in small cement rooms. They stay this way for forty days, which is supposed to drive away the demon. The World Health Organization has started a Chain Free Initiative to try to provide medications that might be more beneficial than superstition.

Fareeba is twelve years old — maybe. She comes from Mazar-e-Sharif — maybe. She was found wandering in the streets and was brought to the mental hospital by strangers — also maybe.

Fareeba lives behind the high stone walls of the women’s mental hospital. She was dropped off at the metal gate by two people who may have been her parents but denied kinship. There is a huge stigma against people with mental illness in Afghanistan, as there is everywhere else.

Behind the walls of the women’s mental hospital, there is sunshine. The women patients are allowed to roam the grounds freely during the day. The walls keep them safe from outsiders who might want to hurt them.

Recently a volunteer from another country helped the patients plant gardens and taught them to care for the plants. Even though it is winter now and nothing is growing, two women are digging in the dirt because that is an activity they enjoy. Others sit and enjoy the sun on their faces. Others follow me around and stare in curiosity at such a funny-looking visitor.

Fareeba cannot speak. She might be able to if she had a therapist to work with her, but there is no one. Judging from her hand gestures and the way she behaves, Fareeba may have autism, but there is no way to have her properly diagnosed, and no one is trained to give her the specialized therapy she requires. There is no next step for her, no place for her to progress to. She is just here, perhaps for the rest of her life.

In many ways, Fareeba is lucky. She is in a place where she and the other patients — all adult women — are kept clean. She has a bed to sleep in with a blanket (unless she makes too much noise at night; then she is put into the room with the big cages, locked away from the others). She is fed every day, and she can go out into the yard at her own whim. The staff are compassionate and competent. No one is being mean to her.

But she has never been to school, never seen a speech therapist, never been given toys and tasks that might help her move forward. Her future is more of the present. This is her life.

Shyah, 14

As different Afghan governments persecuted people with education, trained professionals like doctors and nurses fled the country to save their lives. Under the Taliban, women could not be treated by male doctors, and female doctors were not allowed to work. People who became injured often stayed injured.

A broken leg that is not repaired does not mend on its own. Physical injuries that are not properly treated can lead to long-term difficulties.

SOLA is an organization that tries to repair some of the damage that war and the resulting poverty have caused. It arranges rehabilitative surgery in the United States for kids like Shyah, who are given a home and an education so that when their bodies are repaired, they are better equipped to make something of their lives.

I am from Shamoli, in Parwan Province. I have been at this school for two years, without my family. My mother is dead. She died soon after I was born. My father remarried, and his new wife did not take care of me very well. I can’t say she didn’t like me. I was a baby. I had no personality to like or dislike. Maybe she didn’t like babies. Whatever it was, she didn’t take good care of me.

I was six months old when my legs went all wrong. Someone in my family put me up on a high stack of mattresses and pillows. It was very high and I fell off. My legs got broken and twisted, but there was no treatment, no hospitals or clinics, so they did not heal.

With my legs in bad shape, I guess I was even harder to care for and even more of a problem for my stepmother, so my father did the best thing he knew what to do for me. He put me in an orphanage. That’s where I grew up.

It was okay there. It wasn’t a huge orphanage, just a medium one, and I think that’s better than a really big one. You could get lost in too many kids. When I got old enough I went to school for two hours in the morning, then had lunch, then I went to the mosque in the afternoon for religious studies. It was my life. It was what I knew.

Two years ago some people came to the orphanage looking for kids like me who needed help, and so I came to this school.

This is part home, where I live, part school and part waiting room. All the kids here are waiting to go to other countries for medical treatment, or they have been accepted into foreign universities and they are waiting for their visas to come through.

I have been to the United States once for surgery, and I’m waiting to go again for another operation on my legs. I was sent to Charlotte, North Carolina. I was very happy there. The people in the hospital were very kind to me — so kind that I wasn’t even afraid.

When I came out of the hospital I stayed with an American family to get my strength back. They were great. They had two sons and we all played together. It didn’t matter that they were American and I was Afghan. We played board games, computer games, video games, we went into the city to swim or see a movie. I liked it a lot.

When I was younger I was not interested in studying. My mother was dead and when my father came to see me, he didn’t encourage me. He never went to school. I don’t think he thought I could ever do anything, that my legs were bad and that would be my whole life. I would grow up to be the man with bad legs.

But since coming to SOLA, all that has changed for me. Studying is a very important activity here. All the kids are expected to take it seriously. I am the youngest student here. All the other kids think they can check up on me. “Have you done your homework?” “Don’t you have a test to study for?” There is no chance not to study! So now I am a very good student. My favorite things to study are English and the Qur’an.

There are two kinds of students who live here. Some are like me, waiting to go for medical treatment.

Najib is my friend. He is from Helmand Province. He is a little older than me. On election day two years ago he took his little brother into town on a bicycle. A rocket came. There was an explosion and a tiny piece of shrapnel went into his eye. The rocket killed his little brother.

Najib had one operation but he needs another. It is all arranged for him to go to the United States but now he is waiting for the visa.

When he was in Helmand, he worked for a mechanic and thought he would always work for a mechanic. Now, after meeting more people and learning more things, he wants to be an eye doctor. He gets great grades in sciences like biology and chemistry.

The other students have been granted scholarships to foreign universities. They are waiting for visas, too. The visa officers who work at the embassy are sometimes not helpful. One girl was all set to go away to college, but during her visa interview the officer told her, “How can you go to college when you haven’t been to high school?” But in Afghanistan, school is not regular. She has been tutored and passed the university entrance exam. But the visa officer did not understand that and denied her visa. Another girl was told, “You already have a high school education, you don’t need more than that.” And her visa was denied.

But maybe everyone’s visas will come through soon, and then we’ll go on to the next step for our futures. We are not really family in this school but we feel like family. We are from all over Afghanistan, but it’s like we are all brothers and sisters. Family.

Zuhal, 13

The Kabul Women’s Garden is a special place. In a society where women are not allowed to wander freely, to go outside to stretch their legs when they feel like some fresh air — because either the laws prevent it or customs make it very difficult — the garden gives them a place to walk, unharassed by men.

The eight acres were donated by King Zahir Shah in the 1940s. Not surprisingly, the Taliban closed the garden when they took over. They filled it with garbage and changed its name from Women’s Garden to Spring Garden. Only men went there, to attend the rooster fights that took place in the middle of the rubble.

After the fall of the Taliban, Afghan women, supported by international donations, reclaimed the garden, even doing much of the manual labor required to make it beautiful again — a rare thing in Afghanistan, where the idea of women working in the trades has not really taken hold. Forty-five truckloads of trash were carried away, five thousand rose bushes were planted and all sorts of trees were added.

The Women’s Garden reopened on November 3, 2010. It is a little spot of paradise in the middle of a noisy, busy city. There are pathways, fountains, gazebos and children’s playgrounds. Women can exercise in the fitness center and on the basketball court, enjoy lunch at the restaurant and study at the computer lab or take job training. They can take a tae kwon do class, shop at the small boutiques, or just sit and have quiet for a few minutes.

The garden also has a mosque, built and maintained by women, where women can receive religious instruction from other women.

It is a safe place. The garden has high walls around it and one gate guarded by a male armed guard. After visitors pass through the gate, one of the female intelligence officers checks in bags and under burqas to make sure a suicide bomber or assassin hasn’t slipped through.

Zuhal and her friend have come to the garden to play.

My mother works at home, taking care of us. My father has a job with the government.

I am very good at school. I’m in grade eight and I get lots of praise from my teachers because I work hard and learn fast. My favorite subject to study is English because if you know English, you can get a good job.

But today is a day when there are no classes. I have come here with my friend to the Women’s Garden. My mother came with us, but she has gone inside to a literacy class and we have stayed outside to play. I like it here because only girls are allowed. It’s a place where I can relax.

The garden has a high wall around it that keeps out the noise and dirt of the city. When I am on this side of the wall, I can pretend the whole world is pretty and safe.

The security here is very good. There is a guard out front and you have to be a woman or a girl to get past him. Then there are other guards, women, inside the gate who search everyone’s bag to make sure no one is bringing a bomb into the garden. I don’t know why anyone would want to blow up a garden, but people do strange things. Once that’s over, you can just come into the garden and feel free.

Outside the walls there is a lot of noise from all the cars and trucks on the road. There is a lot of dust and dirt and it is hard to breathe.

Here in the garden, things are different. The walls block out the noise. I know that dust and noise travel, but they don’t seem to come in here. The garden is clean. The air is easier to breathe.

A rainy day in the Women’s Garden.

I don’t feel free outside the garden. Neither does my friend. It’s because of men that we don’t feel free. We feel they are watching us and judging us. They haven’t said anything directly to me or tried to bother me, but my mother tells me to be careful around them, and not to relax out there. She remembers living under the Taliban, when all men were cruel to women, not just the Taliban. She said the Taliban told men that women were bad and a lot of men believed them, and they would treat women badly even if they weren’t part of the Taliban. I try to tell her that things have changed, but she always says, “Things haven’t changed that much!”

So we’re careful when we are out in the world, but behind these walls, in this garden, we don’t have to be careful. We can play and laugh and there is no one to frown at us.

Sometimes my friend and I like to play on the swings, like we’re doing today. Sometimes we run around on all the pathways until we are breathing really hard and we can feel our hearts pounding. Sometimes we feel like being quiet and we just sit on a bench. There are shops as you just come into the garden. Did you see them? They sell dresses and things for hair and for babies. Sometimes we look in the shops or buy a treat from the tea house.

Outside the walls there are a lot of soldiers in the streets. You see them on tanks or army trucks and they carry big machine guns. Some are foreign soldiers, some are Afghan. I am not afraid of them. It’s what I have always seen, ever since I can remember. They don’t bother me because I don’t make trouble for anyone.

I don’t know what I want for the future. That’s a long way off! I guess I want good security and a nice life and a good education. But right now, I just want to swing with my friend.

Parwais, 17

Because of its location, Afghanistan has been at the crossroads for many armies and civilizations. Coins have been found there from ancient Greece and Persia, artifacts from Mongolia and statues from ancient Buddhist societies.

The National Museum of Afghanistan used to hold the most complete record of Central Asian history anywhere in the world, dating all the way back to prehistoric times. But it, too, fell victim to the war.

When the Soviets occupied Afghanistan, Kabul was relatively safe from bombing. A lot of Soviets were stationed there, and they protected the city to protect themselves. When the Soviets left, civil war broke out as the different groups that had been fighting the Soviets turned their guns on each other — each wanted to be the boss of Afghanistan. Bombs started falling on the capital city.

The museum was bombed in 1993, destroying the top floor and leaving it open to looters, who sold the treasures to private collectors all around the world. Although attempts were made to secure the rest of the collection by bolting the doors and bricking up the windows, the looting continued. Most of the collection disappeared.

Then, in March 2001, the Taliban decided to destroy many statues and art objects, including the few that had managed to survive in the museum.

Since the fall of the Taliban, a lot of effort has gone into rebuilding the museum and bringing back as much of the collection as possible. A country’s history — and the things that tell of its history — reminds its people that their present is built on something, and that they are building toward the future.

Parwais is originally from Bagram, north of Kabul. He now works at the National Museum as a cleaner.

We left Bagram during the Taliban. They were very hard to the people there, very bad. So much war, guns, shooting, killing. They killed my father. They burned so many houses and shops. I don’t know why they did these things. Just because they could. No one could stop them.

My older brother took charge of the family after my father was killed. He asked around about where it might be safer and decided to bring us all to Kabul so that we might have some kind of life.

I have never attended school. No one in my family has. It’s just not something we have had the chance to do. I don’t know if I would want to go or not. I don’t know what it means to go.

Even though I never went to school, I am still able to have a good job. I work at the Kabul museum. It is my job to clean the floors and the staircases and anything else that has to be cleaned. It is a very good job because it is inside, so even if the weather is bad, I am warm and dry. The work is not hard and the museum is quiet. Some people spend all their time lifting heavy things or carrying things through traffic, and their back hurts and they get dirty and there is always noise. So this is a very good job.

My cousin had this job before me. When he left it for another job, he suggested that I take over from him. The museum bosses said yes, and now I work hard so they will keep me on.

The best thing about this job is that I get to look at all the exhibits. We have a lot of very old objects here in this museum. Most got broken or even destroyed in the war. Some things were stolen. Some of the things that were lost were found again but they were broken, and if you look at them closely you can see where they were put back together.

The displays have cards next to them that explain what they are. I can’t read the cards — that’s one thing I would like to go to school to learn — but the people who work here explain things to me and I hear them talking to each other. I learn from listening, and it is very interesting.

I didn’t know Afghanistan was so old. I guess I never thought about it until I started working here. Who can spend time thinking about things like that on a regular day? There is too much work to do. But here, I get to think about it all the time. So many people lived here before I did, and their lives were a little bit like mine and they were also different.

I have two favorite things in this museum. One is a statue of a bird that has an oil burner inside. I like to look at it and think about who made it. Why did he think to do such a thing? What made him think it was a good idea? Did the maker use it himself or did he give it to someone else to use?

My most favorite thing is a large bowl made out of clay. It is very old and the colors on it are not fancy but I think they are beautiful. When I look at it I imagine it full of food, and a family is sitting around it having a meal together. Maybe the family that used it hundreds of years ago was not very different from my family.

These are the kinds of things I like to think about when I am doing my cleaning.

The future of Afghanistan? I hope everyone gets a chance to study. Some of us, like me, did not get that chance, but I think it would be better if everyone went to school. There is a lot I don’t know, and the country will be stronger if it is run and helped by people who know things.

The future for me? Well, I just hope I can work here at the museum for a long, long time.

Palwasha, 16

During the reign of the Taliban, the soccer stadium was a torture chamber. Every Friday they would force spectators into the seats to watch prisoners being punished. People were beaten. They had arms cut off. Some were shot in the back of the head or had their heads cut off. Others were strung up on the gallows. Terrible things happened in that stadium.