Chapter 4

Li Mi and His American Friends

Foreign Minister George Yeh and Chief of Staff Chou Chih-jou were unaware that Li Kuo-hui’s Restoration Army had moved to Möng Hsat, away from Yunnan, with orders to neither surrender nor leave Burma. Li Mi, with his typical lack of forthrightness, let that misimpression stand. Lü Kuo-chüan, still in Bangkok and not privy to Li Mi’s plans, was busily working with George Yeh to arrange for the Restoration Army to be interned in Indochina. Still, meeting Rangoon’s August 14 withdrawal deadline looked increasingly unlikely. Distancing Chiang Kai-shek’s government from the Kengtung situation, George Yeh told US officials that Li Kuo-hui’s troops had entered Burma without orders and were no longer part of Taipei’s army. He said Taipei would not object if Burma dealt with the remnants by force in accordance with international law. At the same time, he asked that Washington urge Rangoon to have patience.1

As Li Mi traveled north from Bangkok and met with Li Kuo-hui on the outskirts of the border town of Mae Sai, Lü Kuo-chüan relayed to them from Bangkok an August 11 Chou Chih-jou message ordering Li Mi to take his army into Yunnan. Li Mi’s supporters in Bangkok, including Chargé Sun, Lü Kuo-chüan, and former Tai Li intelligence officer Chiu K’ai-chi concluded that Li Kuo-hui should withdraw before Rangoon’s August 14 deadline to avoid debate in the United Nations that would undoubtedly be unfavorable to Taipei. They too appeared unaware that Li Kuo-hui had already moved most of his troops and dependents to Möng Hsat, deeper into Burma’s Kengtung state and further from Yunnan. Acknowledging Chou Chih-jou’s order, Li Kuo-hui asked for a delay until August 20.2 Meanwhile, in Rangoon, Ambassador Key told U Nu and Ne Win that Taipei had ordered Li Mi’s army to leave Burma and that involving the United Nations would be unnecessary.

The Burmese and the Thai understood that Li Mi’s army was simply moving to another part of Kengtung state. On August 23, Li Kuo-hui left two small rearguard elements west of Tachilek and led the last of his troops through Thailand and back into Burma to occupy Möng Hsat. Lü Kuo-chüan, by then part of the subterfuge, notified Taipei that his Twenty-sixth Army had left Tachilek on its way to Yunnan. He did not specify its routing.3

On August 24, with Li Kuo-hui and his army safely at Möng Hsat, Li Mi returned to Hong Kong. Two days later, Military Attaché Ch’en Cheng-hsi, complicit in the deceit, informed Taipei that there was no way to communicate with Lü Kuo-chüan’s Twenty-sixth Army because it was en route to Yunnan. Chargé Sun made a similar statement to Bangkok newspapers. In Taipei, government officials insisted to the Americans that all able-bodied troops had left for Yunnan with assurances of safe passage from unspecified Burmese officials. They claimed, however, not to have heard from Li Mi’s army since August 23 and to be unsure of its exact location. A skeptical Rankin reminded Washington that Taipei had little solid information about or influence over Li Mi and his soldiers.

Chou Chih-jou and the MND were justifiably suspicious of Li Mi’s “indirect” route to Yunnan. On September 5, by which time Li Mi was back in Hong Kong, the MND again ordered him to lead his troops into Yunnan. It reiterated that order on September 14. From Hong Kong, Li Mi replied that his army was north of Möng Hsat en route to Yunnan but was awaiting additional equipment and supplies before continuing. Dispelling confusion over the army’s whereabouts, an Associated Press (AP) story from Rangoon correctly reported it to be at Möng Hsat.4

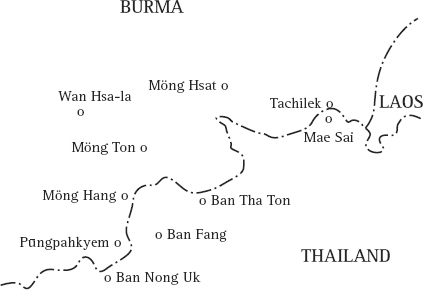

As evidenced in Map 2 above, Möng Hsat was the administrative seat for several villages located in the largest of three interconnecting valleys in southwestern Kengtung, an area many of Li Mi’s officers became familiar with during their service in the Sino-Japanese War. Li Kuo-hui’s troops conscripted local Lahu villagers to build a headquarters and officers’ barracks, as well as a small dam and agricultural irrigation system. Their new base provided easy access to a network of caravan trails linking key locations that would figure prominently in future events—Möng Hpa yak on the Kengtung-Tachilek highway, the mapang caravan center of Möng Hang, and the Thai village of Nong Uk on the border. North of Nong Uk on the primitive road to Möng Hang was P

yak on the Kengtung-Tachilek highway, the mapang caravan center of Möng Hang, and the Thai village of Nong Uk on the border. North of Nong Uk on the primitive road to Möng Hang was P ngpahkyem, where in 1951 Li Mi would open his Yunnan Anticommunist University. Another trail led from Möng Hsat to Wa

ngpahkyem, where in 1951 Li Mi would open his Yunnan Anticommunist University. Another trail led from Möng Hsat to Wa n Hsa-la, an important Salween River ferry crossing that would be the scene of a major Nationalist Chinese battle with the Burma Army.5 From the Thai-Burma border, good roads led to North Thailand’s commercial centers of Lampang and Chiang Mai, from where KMT agents supplied military equipment to Möng Hsat by way of Chiang Dao and the Haw Chinese6 trading center at Ban Fang. Möng Hsat had a small, unpaved auxiliary airfield that the Japanese had built during World War II. It would require major renovation for its neglected runway to handle aircraft but it and the surrounding valley floor offered a parachute drop zone useable most of the year due to Möng Hsat’s relatively light rainfall.7

n Hsa-la, an important Salween River ferry crossing that would be the scene of a major Nationalist Chinese battle with the Burma Army.5 From the Thai-Burma border, good roads led to North Thailand’s commercial centers of Lampang and Chiang Mai, from where KMT agents supplied military equipment to Möng Hsat by way of Chiang Dao and the Haw Chinese6 trading center at Ban Fang. Möng Hsat had a small, unpaved auxiliary airfield that the Japanese had built during World War II. It would require major renovation for its neglected runway to handle aircraft but it and the surrounding valley floor offered a parachute drop zone useable most of the year due to Möng Hsat’s relatively light rainfall.7

Möng Hsat’s Burmese-appointed administrator was a distant relative of Che’li’s t’ussu in Yunnan and well disposed toward the Nationalists when they arrived on August 29.8 Given their general antipathy toward Rangoon and ethnic Burmans, local residents may have initially welcomed the Chinese newcomers without realizing they would become long-term residents. By November 1950, however, any welcome was wearing thin. The newly opened American Consulate Chiang Mai9 reported 2,000 Nationalist Chinese at Möng Hsat looting and otherwise abusing local residents. In December, Li Kuo-hui’s troops arrested Möng Hsat’s administrator and established military rule.10

Some Perspective in Retrospect

Rangoon initially showed only modest discomfort over the presence of armed Nationalist Chinese at Möng Hsat. By late 1950, however, Li Kuo-hui’s growing flirtation with Burma’s Karen and Mon insurgents raised concern in Rangoon. When he refused to hand over a senior Mon insurgent to government authorities, Burmese aircraft bombed Li Kuo-hui’s encampment on November 26. They caused little damage but Li Kuo-hui called them a violation of prior GUB assurances.11

Although the record is not clear, there appears to have been some understanding with Ne Win as Nationalist Chinese troops moved from Tachilek to Möng Hsat. Li Kuo-hui makes that claim in detail and veteran officers from Li Mi’s army have told the authors that they had left Tachilek under a deal with Ne Win that allowed them to remain in a remote part of Kengtung if they stayed out of sight and did not draw Peking’s attention. In return, Ne Win could claim victory over them.12 Such an agreement would explain the apparent lack of serious concern over Li Ko-hui’s troops re-entering Burma after leaving Tachilek for Thailand. It could also have been a basis for the September 6 claim made to Rankin by ROC officials that unspecified Burmese authorities had assured Li Mi’s troops that they could transit Burmese territory en route to Yunnan, despite Rangoon’s public warnings to the contrary.

A safe passage agreement, if it did exist, could also have been a factor in Ne Win’s September 11 resignation from the cabinet, ostensibly in order “to concentrate on military matters.” Ambassador Key surmised that U Nu wanted to intern the CNA remnants to burnish Rangoon’s credentials with Peking. The more pragmatic Ne Win, on the other hand, wanted to get on with fighting Burma’s domestic insurgents. A deal with the Nationalist Chinese would allow the general to concentrate on Rangoon’s internal enemies. Under that scenario, U Nu pushed Ne Win out of the cabinet upon learning that his “victory” at Tachilek left open the possibility of future problems with Peking.13

Li Kuo-hui recounts in his memoirs that he, on Li Mi’s orders, sent a letter proposing a truce to Ne Win during an August visit to Mae Sai. Under his nom de guerre “Li Chung,” Li Kuo-hui assured the Burmese that he would not make trouble if allowed to remain in Burma, thereby leaving the Tatmadaw free to deal with its domestic insurgents. Ne Win allegedly agreed, telling Li Kuo-hui to relocate west of the Kengtung-Tachilek highway, away from the Chinese border, and stay out of sight. Ne Win would then announce that the Nationalist Chinese had broken into small units pursued by the Tatmadaw. Li Kuo-hui claimed to have, again on Li Mi’s orders, accepted Ne Win’s terms on August 22, telling his staff that the deal was to remain a closely guarded secret.14

In light of Taipei’s subsequent duplicity on the subject of its army in Burma, Chiang Kai-shek’s government may have been deliberately misleading Washington regarding the whereabouts and intentions of the Restoration Army as it moved away from Tachilek. As Chargé Rankin suggested, however, Taipei probably did not fully understand what the independent-minded Li Mi was doing. There would have been no reason to expect Li Mi’s troops to be able to fight their way into Yunnan, nor was Li Mi ready to see his troops surrender and accept internment. He needed instead a “temporary” refuge where he could build an army able to survive inside Yunnan.

With the 1950 communist victory in China, American policymakers were at first tepid in their support of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists. After Pyongyang’s June 25 invasion of South Korea, however, the Truman administration found itself reluctantly propping up Chiang Kai-shek’s regime. Peking’s October 1950 open intervention in Korean fighting encouraged Washington’s interest in supporting ROC guerrilla operations against the Chinese Mainland. Only a year after being driven onto Taiwan, the Nationalists claimed, although with considerable exaggeration, to have hundreds of thousands of guerrillas still active on the Mainland. If properly supported, Taipei argued, its guerrillas could tie down PLA forces otherwise available to fight in Korea. To that end, Washington and Taipei soon developed a major program supporting ROC guerrilla operations against the Mainland.

American support for those guerrilla operations came primarily from the CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), which set up shop in East Asia in mid-1949. Specializing in paramilitary operations, OPC’s Far East Division quickly became the largest CIA contingent in East Asia.15 As cover for OPC’s Taiwan-based operations, the CIA registered a proprietary company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Named Western Enterprises, Incorporated (WEI), it was ostensibly an import-export company. Former Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Lt. Col. William R. “Ray” Peers opened WEI’s doors on Taiwan in March 1951.16 By June, its personnel were busy in Taipei as well as at a paramilitary training facility at Tamsui, an hour’s drive north of the capital.

To work with the OPC station, the ROC in January 1951 established its Ta-lu-Kung-tsou-ch’u, or Mainland Operations Department (MOD), under Cheng Kai-min’s 2nd Department (Intelligence) of the Ministry of National Defense. One of the new MOD’s responsibilities was controlling guerrilla forces in Yunnan and elsewhere in southern and southwestern China’s border areas. That mandate had previously been a preserve of Mao Jen-feng’s Pao-mi-chü, or Secrets Preservation Bureau (SPB). Mao Jen-feng resisted the raid on his bureaucratic turf, but when the dust settled, Cheng Kai-min’s MND 2nd Department had gained clear authority over both the SPB and the MOD. The SPB retained operational authority over guerrilla forces while the MOD supported them logistically.

The largest joint MOD-WEI operations supported troops on the offshore islands that remained in Nationalist hands near Fukien province. Headquartered on Quemoy Island, those troops were known as the Fukien Anticommunist Army of National Salvation and their commander was simultaneously designated as Fukien’s governor.17 A similar covert CIA/OPC paramilitary operation would soon support Li Mi in his dual capacities as commander of the Yunnan Anticommunist Army of National Salvation (YANSA) and governor of Yunnan.18

Civil Air Transport, the CIA’s Airline in East Asia

As the Office of Policy Coordination was establishing itself in East Asia, Civil Air Transport (CAT), a largely American-owned but Nationalist Chinese-registered airline, faced bankruptcy as communist advances steadily eliminated its commercial routes and revenues. In May 1949, retired Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault, chairman of CAT’s Board of Directors, was in Washington. He warned of the “domino effect” and lobbied strongly for large-scale US economic and military aid to pro-Nationalist elements holding out in Yunnan and the Muslim provinces of northwest China. Chennault claimed that warlord governors of those provinces had large armies loyal to Chiang Kai-shek and that an airlift of US military assistance and advisors would enable them to resist communist advances.

The China Lobby in the United States supported this “Chennault Plan” vociferously but President Truman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson suspected Chennault’s primary motive was to save his airline from bankruptcy. Neither Truman nor Acheson had much use for Chiang Kai-shek and his corruption-ridden government and they saw no realistic chance of preventing a communist victory in China.19 Despite the administration’s misgivings, American policy began to change as fears of a combined Sino-Soviet threat to East Asia grew.20

As the CIA sought to carry out its role of countering communist expansion in East Asia, OPC wanted a civilian airline to support its covert operations. In early September 1949, as CAT neared bankruptcy, the CIA agreed to finance an operating base for that airline at Sanya, on Hainan Island. The CIA would cover operating costs and, in return, CAT would give priority to CIA missions. Civil Air Transport made its initial flight for the CIA on October 10, 1949, beginning its legendary relationship with that agency, as CAT and later as Air America.21

In March 1950, with CAT’s commercial routes and income dwindling, the State and Defense Departments approved a CIA proposal to pay off the airline’s debts, cover its operating losses, and take a purchase option. In June, three days after North Korean armies attacked the South, a CIA-front company in Delaware secretly purchased Civil Air Transport, which was still an ROC-registered air carrier, and made Chennault chairman of the board. Uneasy over Chennault’s close ties to Chang Kai-shek, the CIA assigned its own people to key positions in the airline’s management. That presence remained modest in numbers and much of the airline’s energy went into commercial flights. It was, however, the CIA’s airline in East Asia when needed.22

The presence of the wartime American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in Bangkok continued into the CIA years. Several former OSS officers from the China-Burma-India theater settled in the Thai capital as businessmen and maintained their affiliations with post-OSS interim American intelligence organizations in Thailand and with influential Thai, many of whom had been wartime comrades-in-arms in the Free Thai movement. Among those former OSS officers were two colleagues from wartime service in Kunming—Lt. Col. Willis Bird and Col. Paul Helliwell. Bird, a businessman before his friend William Donovan recruited him for the OSS, established the small import-export Bangkok Trading Company after the war. Known among his former OSS colleagues as a “con-man” and “operator,”23 he married a sister of Royal Thai Air Force (RTAF) Wing Commander Sitthi Sawetsila, who was then serving as an assistant to police chief Phao Siyanon.24 Helliwell, an attorney and Thailand’s honorary consul general in Miami, maintained his ties to the CIA and incorporated various CIA proprietary companies.25

In Bangkok, political power rested in the hands of the Thai military officers that had seized power in a 1947 coup d’état. Among the most powerful of that “Coup Group” were three army officers—RTA commander Lt. Gen. Phin Chunhawan, his son-in-law Col. Phao Siyanon, and a key Bangkok-based RTA battalion commander named Col. Sarit Thanarat. After seizing power, the Coup Group installed Field Marshal Phibun Songkhram as prime minister. Phibun, who had led Thailand’s wartime government and opportunistically collaborated with the Japanese, had a limited power base of his own but successfully played rivals Phao and Sarit (and their factions) against one another until Sarit ultimately ousted him in a 1957 coup d’état.

Early in 1950, former Free Thai and OSS officers, Coup Group members, and CIA personnel in Bangkok established a secretive group known as the Naresuan26 Committee. Its members included some of the most influential figures in Thailand’s military and political elite, including Prime Minister Phibun Songkhram, RTA Chief Phin Chunhawan, RTAF commander Fuen Ronnaphakat, future prime ministers Sarit Thanarat and Thanom Kittikachon, and American-educated Sitthi Sawetsila as the Committee’s interpreter. Willis Bird was the group’s primary link to the CIA station, bypassing American Ambassador Edwin F. Stanton. Bird’s primary Thai counterpart was Thai National Police Department (TNPD) chief Phao Siyanon, who was then a newly promoted army major general.27

In August 1950, by arrangements made through the Naresuan Committee, a CIA team traveled to Bangkok and, with State and Defense Department approval, negotiated an agreement with Phao to train members of his police force. Phao claimed to have Phibun’s approval but insisted that the prime minister not be involved in the talks. Americans had briefed Foreign Minister Worakan Bancha, another Naresuan member, during a Washington visit but Ambassador Stanton in Bangkok only learned of the project at its initiation, and then only in general terms.

The agreement called for the CIA to equip and train 350 Thai police and military personnel as a counterinsurgency force. They would operate under cover of the ostensibly commercial Southeast Asia Supply Company, known simply as SEA Supply. That CIA proprietary modeled after Western Enterprises on Taiwan, was incorporated in Miami, Florida, with Paul Helliwell handling legal chores.28 Colonel Sherman B. Joost, a former OSS officer, arrived in Bangkok in September 1950 and soon opened SEA Supply’s offices at 10 Pra Athit Road, close to key government offices and the present day Royal Hotel. Its offices later moved to the Grand Hotel, which was then in front of Bangkok’s national sports stadium. In addition to training Thai security forces, SEA Supply would support Li Mi’s secret army during its mid-1951 invasion of Yunnan.

Like WEI on Taiwan, SEA Supply equipped, trained, and advised its clients under an ostensibly commercial contract.29 Its primary mission was to develop an elite paramilitary police force that could defend Thailand’s borders as well as conduct covert anticommunist operations into neighboring countries. In addition to training Thai security forces, SEA Supply would not only support Li Mi’s secret army as it formed in Burma but participate in its mid-1951 invasion of Yunnan. Despite Phao’s legendary corruption, the Americans respected his ability to get things done and found his police more flexible and capable than their army counterparts. Phibun liked the arrangement, as it strengthened Phao’s police as a check on Sarit’s army.30

At one point, close to 300 CIA advisors were working with SEA Supply. Other than the few assigned to the police Special Branch, those advisors had little police experience and the equipment they delivered was for de facto military units, not traditional police officers. That equipment included mortars, machine guns, rifles, medical supplies, and communications equipment from stocks of World War II matériel stored on American-occupied Okinawa, Japan. Later, SEA Supply added tanks, artillery, and aircraft to the police inventory. As ambassador, Stanton was vocally uneasy over SEA Supply’s activities, especially its secrecy regarding their full extent.31

1. I Shan (Li Fu-i), “How General Li Mi Went Alone to the Border Area of Yunnan and Burma to Reorganize a Defeated Army and Counter-attack Mainland China,” pp. 57–72; Patrick Pichi Sun to MFA, Tel., 6/14 and 8/3/1950; MFA to Saigon, Tel., 8/11/1950; Chou Chih-jou to Li Mi and Lü Kuo-chüan (through Ch’en Cheng-hsi), Tel., 8/11/1950; Chou Chih-jou to Li Mi and Lü Kuo-chüan (through Ch’en Cheng-hsi), Tel., 8/13/1950, “ROC Army in Burma, June 14, 1950–January 15, 1954,” MFA Archives, Taipei, ROC. Li Kuo-hui, “Recollections of the Lost Army Fighting Heroically in the Border Area Between Yunnan and Burma,” Part 7, Vol. 14, No. 1 (January 1971), p. 44. Taipei to DOS, Tel. 234, 8/11/1950, RG 59, US National Archives. Taipei to DOS, Tel. 241, 8/11/1950, RG 84, Rangoon Embassy and Consulate, Confidential File 1950–52, Box 10, US National Archives.

2. I Shan (Li Fu-i), “How General Li Mi Went Alone to the Border Area of Yunnan and Burma to Reorganize a Defeated Army and Counter-attack Mainland China,” pp. 57–72. Patrick Pichi Sun to MFA, Tel., 6/14 and 8/3/1950; Patrick Pichi Sun to MND, Report, 9/16/1950; New York (T. F. Tsiang) to MFA, Tel., 8/11/1950 and Saigon (Yin Feng-tsao) to MFA, Tel. 8/14/1950, “The ROC Army in Burma, June 14, 1950–January 15, 1954, Vol. 1,” MFA Archives, Taipei, ROC. Bangkok to DOS, Tel. 162, 8/17/1950, RG 59 and Bangkok to DOS, Tel. 137, 8/11/1950; Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 85, 8/12/1950, RG 84, Rangoon Embassy and Consulate, Confidential File 1950–52, Box 10, US National Archives.

3. Li Kuo-hui, “Recollections of the Lost Army Fighting Heroically in the Border Area Between Yunnan and Burma,” Part 7, p. 47. Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 122, 8/23/1950, Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 155, 9/1/1950; Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 156, 9/2/1950, RG 59, US National Archives. Bangkok to DOS, Tel. 189, 8/24/1950, RG 84, Bangkok Embassy and Consulate, Confidential File, 1950–52, Box 23 and Bangkok, Memo., 9/8/1950, RG 84, Rangoon Embassy and Consulate, Confidential File 1950–52, Box 10, US National Archives. Patrick Pichi Sun to MFA, Tel., 6/14 and 8/3/1950, “The ROC Army in Burma, June 14, 1950–January 15, 1954,” MFA Archives, Taipei, ROC. Military Attaché Bangkok to War Office London, Memo., MA/311/B/50, 9/18/1950, FO 371/83113, UK National Archives. Kuomintang Aggression Against Burma, p. 213.

4. Taipei to DOS, Tel. 370, 9/12/1950, Box 9; Bangkok to Rangoon Tel. 11, 8/29/1950; Taipei to DOS, Tel. 346, 9/6/1950, Box 10, Rangoon Embassy and Consulate, Confidential File 1950–52, Box 10, US National Archives. Ch’en Cheng-hsi to MND, Tel., 8/26/1950; Bangkok (Patrick Pichi Sun) to MFA, Tel. 266, 8/31/1950; Chou Chih-jou to Li Mi, Tel., 9/5/1950; Chou Chih-jou to Li Mi, Tel., 9/14/1950; and Li Mi to Chou Chih-jou, Tel., 9/15/1950, “ROC Army in Burma, June 14, 1950–January 15, 1954,” MFA Archives, Taipei, ROC. Bangkok to DOS, Tel. 217, 9/1/1950, and DOS, Memo., 9/19/1950, RG 59, US National Archives.

5. T’an Wei-ch’en, History of the Yunnan Anticommunist University, pp. 72–73. Catherine Lamour, Enquête sur une Armée Secrète, p. 76.

6. Haw Chinese are generally Muslims, and are well-assimilated throughout North Thailand.

7. “Accessibility to Möng Hsat (20-32N, 99-16E),” CIA Database, 5/26/1953, CIARDP91T01172R000200300036-9, US National Archives.

8. Li Kuo-hui, “Recollections of the Lost Army Fighting Heroically in the Border Area Between Yunnan and Burma” Part 6, Vol. 13, No. 12 (December 1970), p. 48. Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 156, 9/2/1950, and Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 156, 9/2/1950, RG 59, US National Archives. “Chinese Nationalist Troops in Kengtung,” CIA Database, 11/1/1950, CIA-RDP82-00457R006100660010-5, US National Archives.

9. Some have suggested that the US Consulate in Chiang Mai was opened specifically to support Li Mi’s enterprise in Burma. That assumption is not supported by official documents and interviews with former State Department officers.

10. Bangkok to DOS, Tel. 573, 11/16/1950, RG 84, Bangkok Embassy and Consulate, Confidential File 1950–1952, Box 23; Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 426, 12/28/1950; Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 430, 12/29/1950, RG 59, US National Archives.

11. Li Kuo-hui, “Recollections of the Lost Army Fighting Heroically in the Border Area Between Yunnan and Burma,” Part 6, p. 48. Bangkok to DOS, Tel. 1119, 2/8/1951; Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 426, 12/28/1950; and Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 430, 12/29/1950, RG 59, US National Archives.

12. Li Kuo-hui, “Recollections of the Lost Army Fighting Heroically in the Border Area Between Yunnan and Burma,” Part 6, pp. 46–48. Catherine Lamour mentions an August 23 ceasefire but does not give details in Enquête sur une Armée Secrète, p. 45.

13. Rangoon to DOS, Tel. 179, 9/12/1950, RG 84, Rangoon Embassy and Consulate, Confidential File 1950–52, Box 8, US National Archives.

14. Li Kuo-hui, “Recollections of the Lost Army Fighting Heroically in the Border Area Between Yunnan and Burma,” Part 6, p. 47. Catherine Lamour, Enquête sur une Armée Secrète, p. 45.

15. Frank Holober, Raiders of the China Coast: CIA Covert Operations During the Korean War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000), pp. 5–7 and 72–74. John Ranelagh, The Agency: The Rise and Decline of the CIA (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1986), pp. 67–69. William M. Leary, Perilous Missions: Civil Air Transport and CIA Operations in Asia (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1984), pp. 124–125.

16. Once WEI was up and running, Peers returned to the Army and fought with distinction in Korea and Vietnam.

17. Frank Holober, Raiders of the China Coast, pp. 5–7, 7–8, 13, 26, and 32.

18. It was standard MND practice to designate its guerrilla armies on the Mainland as “anticommunist national salvation armies” of the geographic areas in which they operated. Liu Yuan-lin, Eventful Records in Yunnan and Burma Border Area–Recollections of Liu Yuan-lin’s Past 80 Years, p. 104.

19. William M. Leary, Perilous Missions, pp. 67–70. William M. Leary and William W. Stueck, “The Chennault Plan to Save China: U.S. Containment in Asia and the Origins of the CIA’s Aerial Empire, 1949–50,” Diplomatic History, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Fall 1984), pp. 349–64.

20. William M. Leary, Perilous Missions, p. 104. Mike Gravel, The Pentagon Papers: The Defense Department History of United States Decisionmaking on Vietnam, Vol. 1 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1971), pp. 361–362.

21. William M. Leary, Perilous Missions, pp. 70–72, 76–78, 81–81, 84–86, and 88–89. Liu, Military History, pp. 269–70. Tong Te Kong and Li Tsung-jen, The Memoirs of Li Tsung-jen, (Boulder, CO: Westview Press), p. 546.

22. William M. Leary, Perilous Missions, pp. 105–109 and 110–113. Felix Smith, China Pilot, pp. 193–194. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on International Relations, “United States Policy in the Far East,” Vol. 8, Part 2, pp. 492–493.

23. In 1959, Congressional testimony alleged Bird had bribed a US aid official in Laos to obtain a construction contract. None of the allegations against Bird were ever proven in court but it was said in Bangkok that Bird remained in Thailand to avoid potential legal problems were he to return to the United States. R. Harris Smith, OSS: The Secret History of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), p. 273. Anond Srivardhana int. by Richard M. Gibson, 9/6/2002, Santa Clara, CA.

24. Sitthi worked closely with US diplomats throughout a distinguished career that included service as head of Thailand’s National Security Council (NSC) and as Foreign Minister. He was later named to the King’s Privy Council. Daniel Fineman, A Special Relationship, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1997), pp. 133–134. Anond Srivardhana int. by Richard M. Gibson, 9/6/2002, Santa Clara, CA.

25. R. Harris Smith, OSS, p. 326. Daniel Fineman, A Special Relationship, p. 134. William M. Leary, Perilous Missions, p. 70. Anond Srivardhana int. by Richard M. Gibson, 9/6/2002, Santa Clara, CA., p. 326.

26. Named after Thailand’s King Naresuan the Great who ruled from 1590–1610, the period of Thailand’s greatest territorial expansion.

27. Daniel Fineman, A Special Relationship, pp. 133–134. Thomas Lobe, United States National Security Policy and Aid to the Thailand Police, Monograph Series in World Affairs, Vol. 14, Book 2. (Denver, CO: University of Denver Graduate School of International Studies, 1977), p. 20. John E. Shirley int. by Richard M. Gibson, 2/18/1998, Bangkok. Anond Srivardhana int. by Richard M. Gibson, 9/6/2002, Santa Clara, CA.

28. Thomas Lobe, United States National Security Policy and Aid to the Thailand Police, p. 20. Anond Srivardhana int. by Richard M. Gibson, 9/6/2002, Santa Clara, CA. John E. Shirley int. by Richard M. Gibson, 2/18/1998, Bangkok, Thailand.

29. Daniel Fineman, A Special Relationship, p. 134. Anond Srivardhana int. by Richard M. Gibson, 9/6/2002, Santa Clara, CA. John E. Shirley int. by Richard M. Gibson, 2/18/1998, Bangkok, Thailand.

30. Anond Srivardhana int. by Richard M. Gibson, 9/6/2002, Santa Clara, CA. Daniel Fineman, A Special Relationship, pp. 133–134. Thomas Lobe, United States National Security Policy and Aid to the Thailand Police, p. 20. Jack Shirley int. by Richard M. Gibson, 2/18/1998, Bangkok.

31. Thomas Lobe, United States National Security Policy and Aid to the Thailand Police, pp. 20 and 23. John E. Shirley int. by Richard M. Gibson, 2/18/1998, Bangkok, Thailand.