Chapter 25

Postscript

Thailand’s government rewarded the KMT for their service against the country’s communist insurgents. On October 17, 1975, the government instructed the Defense and Interior Ministries to develop a plan under which KMT-affiliated refugees would receive resident alien status en route to accelerated naturalization. Six months later, in April 1976, the Cabinet approved suspension of the country’s yearly quota for naturalization of foreigners. After that seemingly good start, however, it would be another two years before the RTG bureaucracy agreed upon necessary legal steps for naturalizing the KMT soldiers and their families. In the meantime, KMT soldiers that had fought communist insurgents in Chiang Rai continued to die as they protected strategic road construction projects in that province and elsewhere in North Thailand. Finally, in the summer of 1978, with Kriangsak Chomanan as prime minister, the RTG began to implement the 1976 Cabinet decision giving citizenship to the former Nationalist Chinese soldiers and their families.

In a series of decrees between August 1978 and May 1981, the Cabinet approved citizenship for four large increments of KMT refugees—5,179 soldiers and family members that had participated in anticommunist operations in north Thailand. Priority was given to families of those that had fallen in the Khao Kho and Khao Ya campaigns.1 On Supreme Command recommendation, the Cabinet approved permanent alien residence status for a larger, fifth group of 8,549 soldiers and family members that had not been directly involved in the above operations. Most members of that fifth group were, over time, granted Thai citizenship on a case-by-case basis.

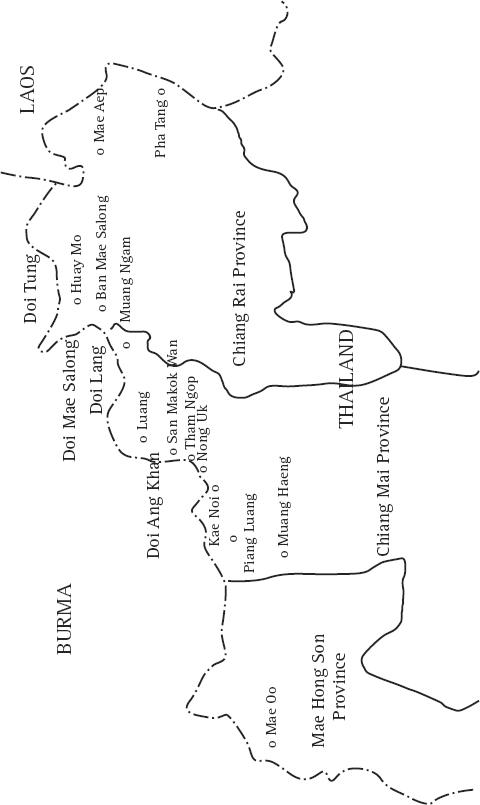

In February 1984, Supreme Command transferred its security responsibilities for the KMT to the Royal Thai Army. In April, the RTA established Task Force 327, headquartered at Mae Rim, to manage security and socio-economic development in KMT resettlement villages like those shown in Map 14. In June, the naturalization program was transferred to the Ministry of Interior, which promptly reinstated the former 200 per year quota for new citizens and reverted to the government’s cumbersome pre-1978 administrative procedures, thereby prolonging the naturalization process.2

Allowing for population growth after 1984, perhaps 20,000 KMT soldiers and dependents of the Third and Fifth Armies at some point became eligible for naturalization. Removing from that number the 13,728 given citizenship between 1978 and 1983, in 1984 there remained 6,272 KMT persons (1,281 former soldiers and 4,991 dependents) awaiting naturalization. At the rate of 200 every year, it would require at least 31 years to naturalize all of those not covered by the 1978–1983 actions. At the end of 2010, 25 years had passed. While awaiting citizenship, however, the former KMT are legal resident aliens able to own land, travel freely, and earn livelihoods anywhere in Thailand.

Over the years, many KMT refugees, especially those who did not immediately gain Thai citizenship, moved to Taiwan to study, look for jobs or rejoin relatives. Those able to establish Mainland China as their birthplace generally received ROC citizenship. Others, such as Sino-Burmese and stateless hill tribe residents of the tri-border region were not eligible for ROC citizenship but were allowed to reside permanently on Taiwan. Among those remaining in Thailand, many of the younger generation have married ethnic Thai or Sino-Thai and social integration between refugees and native-born Thai is well along.4

The ROC did not forget its soldiers. In 1997, Taiwan belatedly approved monetary compensation for its former soldiers and their families in North Thailand. If the soldier was deceased, the money was to go to his family. According to Kung Ch’eng-yeh,5 the former Free China Relief Association representative in Chiang Mai, some 2,400 people were scheduled to receive ROC payments for their service, and presumably did.6

Detracting from the overall success story of the KMT remnants in Thailand was their continued involvement in illicit drug trafficking. Into the 1990s, KMT Third and Fifth Armies and affiliated groups remained among the preeminent Golden Triangle trafficking organizations. Beginning in the late 1980s, however, Chang Ch’i-fu (by then known as Khun Sa) and his Shan United Army eclipsed the KMT trafficking groups, in part by defeating them in a series of fights inside Burma. Over time, the aging KMT armies were demobilized and Southwest Asia largely replaced Southeast Asia in the world heroin trade. Illegal narcotics remain a commercial pursuit for some of the former Nationalist Chinese in North Thailand but on a smaller and more manageable scale for Thai authorities.

Nationalist Chinese soldiers that entered the Golden Triangle in 1950 eventually blended into North Thailand’s society. As of the year 2000, Thai authorities estimated that as many as 20,000 people with some tie to the KMT lived in 84 villages in six districts along the Burmese and Lao borders in Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Mae Hong Son provinces. Today, those descendants of Chiang Kai-shek’s wartime army are Thai, in name as well as spirit.7

Their parents, however, paid a high price for the children’s prosperity. There are various memorials in North Thailand to Nationalist Chinese soldiers who lost their lives fighting communists for the Royal Thai Government. Near Khao Kho there is a monument to those killed while working as security guards for road building. A Third Army cemetery is in Tham Ngop and the Fifth Army buried its dead at Mae Salong. At the Ban Hua Wiang cemetery near Chiang Khong, a monument is dedicated specifically to the 172 KMT soldiers killed while fighting under direct RTG control. Those include the 81 lost in the 1970–1973 operations on Doi Luang, Doi Yao, and Doi Pha Mon and soldiers killed while providing security for road construction. Added later were the names of the 26 KMT killed in action during the Khao Ya operation and the names of Thai soldiers who fell while fighting alongside the Nationalist Chinese.8

1. Royal Thai Army, Task Force 327, Former Chinese Nationalist Military Refugees, pp. 110–112.

2. Royal Thai Army, Task Force 327, Former Chinese Nationalist Military Refugees, pp. 48–49.

3. Ban Piang Luang, Ban Muang Haeng, Ban Kae Noi, Ban Nong Uk, Ban Tham Ngop, and Ban Luang.

4. Lo Chiu-chao (Mrs. Chin Yee huei), presentation sponsored by the Study Group on Overseas Chinese, Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, Taipei, 9/1/2009.

5. Kung Ch’eng-yeh joined Li Mi after his family’s murder by communist officials. In Chiang Mai, he carried out economic development programs in CIF refugee villages.

6. Kung Ch’eng-yeh int. by Richard M. Gibson, 8/13/1997, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

7. Bangkok Post (internet version), 7/1/2000.

8. Kanchana Prakatwuthisan, The 93rd Division: Nationalist Chinese Refugee Soldiers on Pha Tang Mountain, pp. 169 and 197.