1

The Distinctions of Cultures Without Distinction

Introduction

Nothing could better signify the ‘complete disappearance of a culture of meaning and aesthetic sensibility,’ says postmodern cultural commentator Jean Baudrillard, than ‘a spinning of strobe lights and gyroscopes streaking the space whose moving pedestal is created by the crowd’ (Baudrillard 1982: 5). Baudrillard’s dismissal of the discotheque as the lowest form of contemporary entertainment reiterates a well-established view. Dance cultures have long been seen to epitomize mass culture at its worst. Dance music has been considered to be standardized, mindless and banal, while dancers have been regarded as narcotized, conformist and easily manipulated. Even Theodor Adorno, an early theorist of mass culture, reserved some of his most damning prose for the ‘rhythmic obedience’ of jitterbug dancers, arguing that the ‘music immediately expressed their desire to obey’ and that its regular beat suggested ‘coordinated battalions of mechanical collectivity … Thus do the obedient inherit the earth’ (Adorno 1941/1990: 312).

For many years, discotheques and dance music have even been excluded from popular music’s own canons. Rock criticism and much pop scholarship have tended to privilege ‘listening’ over dance musics, visibly performing musicians over behind-the-scenes producers, the rhetorically ‘live’ over the ‘recorded’ and hence guitars over synthesizers and samplers. Until the mid-eighties, successive genres of dance music tended to be dismissed as irrelevant fads or evoked as symbols of all that was not radical or innovative in music. Although these ideas are no longer held by as many music critics as they once were, the old rock canon persists in many spheres. For example, the following entry on disco music from the 1989 edition of the Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music typifies the opinion of the old guard:

Dance fad of the 70s with profound and unfortunate influence on popular music … it had a disastrous effect on music for two related reasons, the producers and the technology … producers, who already had too much power, used drum machines, synthesizers and other gimmicks at the expense of musical values … most disco hitmakers were virtually anonymous, and the anonymity has translated into the sameness of pop music in the 80s. (Clarke 1989: 344)

The purpose of this book is not to celebrate the creativity of dance culture (it seems to me that this needs no proving), nor to canonize dance music nor elevate the status of discotheques. In fact, except for some discussion of the taste war between disc-dancers and the Musicians’ Union in the first chapter, I don’t investigate in depth the values of people outside dance culture. Instead, I am concerned with the attitudes and ideals of the youthful insiders whose social lives revolve around clubs and raves.

Despite having once been an avid clubber, I was an outsider to the cultures in which I conducted research for several reasons. First and foremost, I was working in a cultural space in which everyone else (except the DJs, door and bar staff, and perhaps the odd journalist) was at their leisure. Not only did I have intents and purposes that were alien to the rest of the crowd, but also for the most part I tried to maintain an analytical frame of mind that is truly anathema to the ‘lose yourself and ‘let the rhythm take control’ ethos of clubs and raves.* Two demographic factors – my age and nationality – further contributed to this detachment. I began my research when I was twenty-three and slowly aged out of the peer group I was studying, acquiring increments of analytical distance with each passing year. As a North American investigating British clubs and raves, I was also, quite literally, a stranger in a strange land. Although club culture is a global phenomenon, it is at the same time firmly rooted in the local. Dance records and club clothes may be easily imported and exported, but dance crowds tend to be municipal, regional and national. Dance styles, for example, which need to be embodied rather than just bought, are much less transnational than other aspects of the culture.

‘Club culture’ is the colloquial expression given to youth cultures for whom dance clubs and their eighties offshoot, raves, are the symbolic axis and working social hub. The sense of place afforded by these events is such that regular attenders take on the name of the spaces they frequent, becoming ‘clubbers’ and ‘ravers’. The territorial affiliations of most post-war youth subcultures have been more ambiguous and numerous than club cultures, even if we envision hippies at rock festivals, skinheads on football terraces and punks at small ‘live’ gigs. Club cultures, by contrast, are persistently associated with a specific space which is both continually transforming its sounds and styles and regularly bearing witness to the apogees and excesses of youth cultures.

Club cultures are taste cultures. Club crowds generally congregate on the basis of their shared taste in music, their consumption of common media and, most importantly, their preference for people with similar tastes to themselves. Taking part in club cultures builds, in turn, further affinities, socializing participants into a knowledge of (and frequently a belief in) the likes and dislikes, meanings and values of the culture. Clubs and raves, therefore, house ad hoc communities with fluid boundaries which may come together and dissolve in a single summer or endure for a few years. Crucially, club cultures embrace their own hierarchies of what is authentic and legitimate in popular culture – embodied understanding of which can make one ‘hip’. These distinctions – their cultural logics and socio-economic roots – are the main subject of this book.

Club cultures are riddled with cultural hierarchies. My intention is to explore three principal, overarching distinctions which can be briefly designated as: the authentic versus the phoney, the ‘hip’ versus the ‘mainstream’, and the ‘underground’ versus ‘the media’. Each distinction opens up a world of meanings and values which is explored in a separate and self-contained chapter. Each chapter, in turn, excavates the sociological sources and pursues the cultural ramifications of the distinction in question. As such, the three ensuing chapters enter into slightly different debates about youth, music, media and culture. However, they are all unified by an unbroken concern with the problem of cultural status.

In the first part of the book, I explore the distinction between the authentic and the inauthentic, the ‘real’ happening and the non-event, original dance records and formula pop. Although the authenticities of ‘live’ performance have been comprehensively researched, little has been written about the new authenticities attributed to records and recorded events. Even though they enjoy many affinities, club cultures espouse dynamics of distinction sufficiently different from those of live music cultures to justify coining a new term and discussing them as disc cultures. For example, within disc cultures, recording and performance have swapped statuses: records are the original, whereas live music has become an exercise in reproduction. Club cultures celebrate technologies that have rendered some traditional kinds of musicianship obsolete and have led to the formation of new aesthetics and judgements of value. Producers, sound engineers, remixers and DJs – not song-writing guitarists – are the creative heroes of dance genres. As a result, when a ‘performance’ is called for, it may entail hiring a model and dancers to lip-synch to the sampled vocals while the track’s composer prances behind a computer keyboard or DJ console at the back of the stage. The clubber consensus is that these kinds of appearance are often laughably inauthentic attempts to visualize something which is usually best left in its pure sonic state.

The history of these shifting authenticities between the ‘live’ and the quintessentially recorded is primarily dependent on changing modes of music consumption. The story goes back to the ‘record hops’ of the 1950s and involves the rise of the discotheque and the decline of live music for public dancing. Discotheques institutionalized the practice of dancing to discs; they were crucial to the enculturation of records, the material process upon which their authentication is predicated. This history therefore entails not just sounds, but changing finances and labour relations, novel locations and transformed architectural environments, new ‘youth’ audiences and new music professions. I explore these in order to grasp the issue of musical authenticity not just as a vague sensibility or aesthetic, but as a cultural value anchored in concrete, historical practices of production and consumption.

The second distinction I investigate is one principally discussed as that between the ‘hip’ world of the dance crowd in question and its perpetually absent, denigrated other – the ‘mainstream’. This contrast between ‘us’ and the ‘mainstream’ is more directly related to the process of envisioning social worlds and discriminating between social groups. Its veiled elitism and separatism enlist and reaffirm binary oppositions such as the alternative and the straight, the diverse and the homogeneous, the radical and the conformist, the distinguished and the common. The mainstream is a trope which, once prised open, reveals the complex and cryptic relations between age and the social structure.

The mainstream is the entity against which the majority of clubbers define themselves. Can the mainstream be a majority? What is its exact status? Is it a minority, a myth, neither or both? More to the point, how does the ‘mainstream’ function for those who invoke it? What are the social differences implied by clubber discourses about the mainstream? And, what problems or possibilities does the belief pose for researchers investigating the cultural organization of youth?

To some degree, the mainstream stands in for the masses – discursive distance from which is a measure of a clubber’s cultural worth. Youthful clubber and raver ideologies are almost as anti-mass culture as the discourses of the artworld. Both criticize the mainstream/masses for being derivative, superficial and femme (Huyssen 1986). Both conspicuously admire innovative artists, but show disdain for those who have too high a profile as being charlatans or overrated media-sluts. Of course, they differ in many ways. Crucially, rather than the artworld’s dread of ‘trickle down’, the problem for underground subcultures is a popularization by a gushing up to the mainstream. These metaphors are not arbitrary; they betray a sense of social place. Subcultural ideology implicitly gives alternative interpretations and values to young people’s, particularly young men’s, subordinate status; it re-interprets the social world.

In the final section of the book, I examine the distinction between the ‘underground’ and ‘the media’ which encompasses a series of further contrasts including the esoteric versus the exposed, the exclusive versus the accessible, the pure versus the corrupted, the ‘independent’ versus the ‘sold out’. Club undergrounds see themselves as renegade cultures opposed to, and continually in flight from, the colonizing co-opting media. To be ‘hip’ is to be privy to insider knowledges that are threatened by the general distribution and easy access of mass media. Like the mainstream, ‘the media’ is therefore a vague monolith against which subcultural credibilities are measured.

But the relations between various media and club cultures – as well as clubber and raver discourses about individual media – are complex and varied. To make any sense of their dynamics, one needs to differentiate between micro, niche and mass media, then to consider the disparate consequences of affirmative or critical, explicit or allusive coverage within each of these spheres. For example, disapproving ‘moral panic’ stories in mass circulation tabloid newspapers often have the effect of certifying transgression and legitimizing youth cultures. How else might youthful leisure be turned into revolt, lifestyle into social upheaval, difference into defiance? Approving reports in mass media like tabloids or television, however, are the subcultural kiss of death. Nevertheless both kinds of coverage tend to lead to a quick abandonment of the key insignia of the culture. For example, Smiley-face T-shirts were cast off as uncool and the word ‘acid’ was dropped from club names and music genre classifications as soon as ‘acid house’ became a term familiar to general readers of national newspapers.

Disparagement of the inauthentic, the mainstream and the media is prevalent amongst all kinds of club cultures. Interest in authenticity and distinction would seem to be the norm. Nevertheless, the subcultural ideologies I investigate are those of predominantly straight and white club and rave cultures. Similar ‘underground’ discourses operate in gay and lesbian clubs but, as the alternative values involved in exploring sex and sexuality complicate the situation beyond easy generalization, I concentrate on their heterosexual manifestation. Moreover, ‘campness’ rather than ‘hipness’ may be a more appropriate way to characterize the prevailing cultural values of these communities (cf. Sontag 1966; Savage 1988).* And, although I did substantial research in Afro-Caribbean and mixed-race clubs, the book more thoroughly (but not exclusively) analyses the cultural worlds of the white majority. Despite the fact that black and white youth cultures share many of the same attitudes and some of the same musics, race is still a conspicuous divider.

Over the past few decades, there has been much productive inquiry into the divide between high and popular culture. Some work has attempted to deconstruct the elitist assumptions that lie behind high theorists’ denigration of ‘mass culture’ and has considered the problem in the light of debates about modernism and postmodernism (cf. Huyssen 1986; MacCabe 1986). Other studies have traced the upward or downward mobility of artistic figures and forms, like the transformation of Shakespeare from a people’s playwright into a cultural deity or the process by which jazz was ‘elevated’ from being a music of nightclubs to one of university music departments (cf. Levine 1988; Ross 1989). Some research has examined the relation between cultural hierarchies and social ones, attempting to demonstrate that personal taste is not the result of an individual’s immanent nature, but of family background, education and class (cf. Gans 1974; Bourdieu 1984). Still other investigations have found that cultural forms, previously considered trivial, actually threaten the social order in significant ways and theories of the symbolic ‘resistances’ of the popular to ‘dominant’ culture have been developed (cf. Hall and Jefferson 1976; Hebdige 1979).

Comparatively little attention, however, has been paid to the hierarchies within popular culture. Although judgements of value are made as a matter of course, few scholars have empirically examined the systems of social and cultural distinction that divide and demarcate contemporary culture, particularly youth cultured.† Feminist analyses are a general exception to this rule, but they tend to restrict their inquiry to criticizing the devaluation of the feminine and to examining the subordinate position of girls (cf. McRobbie 1991). They have not extended this insight to a general examination of the way youth cultures are stratified within themselves or the manner in which young people seek out and accumulate cultural goods and experiences for strategic use within their own social worlds. The analysis of these cultural pursuits as forms of power brokering is essential to our understanding not only of youth and music cultures in particular but of the dynamics of popular culture in general.

Studies of popular culture have tended to embrace anthropological notions of culture as a way of life but have spurned art-oriented definitions of culture which relate to standards of excellence (cf. Williams, 1976 and 1981). High culture is generally conceived in terms of aesthetic values, hierarchies and canons, while popular culture is portrayed as a curiously flat folk culture. One is depicted as vertically ordered, the other as horizontally organized. Of course, consumers of popular culture have been depicted as discerning, with definite likes and dislikes, but these tastes are rarely charted systematically as ranked standards.

In Britain and to a lesser extent North America and Australia, studies of popular culture – particularly studies of youth subcultures – have been dominated by a tradition associated with the 1970s work of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham, England. Given that so many years have passed, it should come as no surprise that this study is indebted to their work but is nevertheless distinctly ‘post-Birmingham’ in several ways. First, this book doesn’t adopt their theoretical definitions of ‘subcultures’ for the main reason that I found them to be empirically unworkable (cf. chapter 4). Instead, I use the term ‘subcultures’ to identify those taste cultures which are labelled by media as subcultures and the word ‘subcultural’ as a synonym for those practices that clubbers call ‘underground’.

In this respect, my work harks back to the studies of Chicago School sociologists whose concern for researching empirical social groups always took precedence over their elaboration of theory. In fact, Howard Becker offers a compelling analysis of ‘distinction’ under another name in his study of a ‘deviant’ culture of musicians in the 1940s (published in Outsiders, 1963). The white jazz musicians in Becker’s study saw themselves as possessing a mysterious attitude called ‘hip’ and dismissed other people, particularly their audience, as ignorant ‘squares’. Similarly, in the early sixties, Ned Polsky researched the social world of Greenwich Village Beatniks, finding that the Beats distinguished not only between being ‘hip’ and ‘square’, but added a third category of the ‘hipster’ who shared the Beatnik’s fondness for drugs and jazz, but was said to be a ‘mannered show off regarding his hipness’ (Polsky 1967: 149). The overwhelming majority of Beats were neither exhibitionists nor publicity seekers but precisely the opposite. According to Polsky, ‘the cool world [was] an iceberg, mostly underwater’ (Polsky 1967: 151).

Second, the classic Birmingham subcultural studies tended to banish media and commerce from their definitions of authentic culture. In Resistance Through Rituals, the authors position the media in opposition to and after the fact of subculture (cf. Hall and Jefferson 1976). In Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Dick Hebdige sees media and commerce as ‘incorporating’ subcultures into the hegemony, swallowing them up and effectively dismantling them. (Hebdige 1979). In Profane Culture, Paul Willis argues that violent acts of appropriation are necessary to transform the ‘shit of capitalist production’ into the sacred objects of authentic youth subcultures (Willis 1978: 170). By contrast, I attempt to problematize the notion of authenticity and see various media and businesses as integral to the authentication of cultural practices. Here, commercial culture and popular culture are not only inextricable in practice, but also in theory.

Third, the book does not offer a synchronic interpretation of subcultures or textual analysis of their sounds and styles, but an analysis explicitly concerned with cultural change. (For all their concern for rebellion and resistance, this tradition gave little consideration to social change!) The book explores cultural transformations in two periods: through archival research, it recounts a history of the evolving authenticities of records and recorded events since the Second World War; and through ethnographic research, it examines the complex cultural and media processes by which acid house ‘subculture’ crystallized and turned into the rave ‘movement’ between 1988 and 1992.

Finally, this book is not about dominant ideologies and subversive subcultures, but about subcultural ideologies. It treats the discourses of dance cultures, not as innocent accounts of the way things really are, but as ideologies which fulfil the specific cultural agendas of their beholders. Subcultural ideologies are a means by which youth imagine their own and other social groups, assert their distinctive character and affirm that they are not anonymous members of an undifferentiated mass. In this way, I am not simply researching the beliefs of a cluster of communities, but investigating the way they make ‘meaning in the service of power’ – however modest these powers may be (Thompson 1990: 7). Distinctions are never just assertions of equal difference; they usually entail some claim to authority and presume the inferiority of others.

In trying to make sense of the values and hierarchies of club culture, I’ve drawn from the work of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, particularly his book Distinction (1984) and related essays on the links between taste and the social structure. Bourdieu writes extensively about what he calls cultural capital or knowledge that is accumulated through upbringing and education which confers social status. Cultural capital is the linchpin of a system of distinction in which cultural hierarchies correspond to social ones and people’s tastes are predominantly a marker of class. For instance, in Britain, accent has long been a key indicator of cultural capital, and university degrees have long been cultural capital in institutionalized form. Cultural capital is different from economic capital. High levels of income and property often correlate with high levels of cultural capital, but the two can also conflict. Comments about the ‘nouveau riche’ or the ‘flash’ disclose the possible frictions between those rich in cultural capital but relatively poor in economic capital (like artists or academics) and those rich in economic capital but less affluent in cultural capital (like business executives and professional football players).

One of the many advantages of Bourdieu’s schema is that it moves away from rigidly vertical models of the social structure. Bourdieu locates social groups in a highly complex multi-dimensional space rather than on a linear scale or ladder. His theoretical framework even includes discussion of a third category – social capital – which stems not so much from what you know as who you know (and who knows you). Connections in the form of friends, relations, associates and acquaintances can all bestow status. The aristocracy has always privileged social over other forms of capital, as have many private members’ clubs and old boys’ networks. The notion of social capital is also useful in explaining the power of fame or of being known by those one doesn’t know, particularly when the famous consolidate their social capital in marriage (hence the stop-press news coverage of the marital merger of Michael Jackson and Lisa Marie Presley).

In addition to these three major types of capital – cultural, economic and social – Bourdieu elaborates many subcategories of capital which operate within particular fields such as ‘linguistic’, ‘academic’, ‘intellectual’, ‘information’ and ‘artistic’ capital. One characteristic that unifies these capitals is that they are all at play within Bourdieu’s own field, within his social world of players with high volumes of institutionalized cultural capital. However, it is possible to observe subspecies of capital operating within other less privileged domains. In thinking through Bourdieu’s theories in relation to the terrain of youth culture, I’ve come to conceive of ‘hipness’ as a form of subcultural capital.

Although subcultural capital is a term that I’ve coined in relation to my own research, it is one that accords reasonably well with Bourdieu’s system of thought. In his essay, ‘Did you say Popular?’, he contends that ‘the deep-seated “intention” of slang vocabulary is above all the assertion of an aristocratic distinction’ (Bourdieu 1991: 94). Nevertheless, Bourdieu does not talk about these popular ‘distinctions’ as ‘capitals’. (Perhaps he sees them as too paradoxical in their effects to warrant the term?) However, I would argue that clubs are refuges for the young where their rules hold sway and that, inside and to some extent outside these spaces, subcultural distinctions have significant consequences.

Subcultural capital confers status on its owner in the eyes of the relevant beholder. In many ways it affects the standing of the young like its adult equivalent. Subcultural capital can be objectified or embodied. Just as books and paintings display cultural capital in the family home, so subcultural capital is objectified in the form of fashionable haircuts and well-assembled record collections (full of well-chosen, limited edition ‘white label’ twelve-inches and the like). Just as cultural capital is personified in ‘good’ manners and urbane conversation, so subcultural capital is embodied in the form of being ‘in the know’, using (but not over-using) current slang and looking as if you were born to perform the latest dance styles. Both cultural and subcultural capital put a premium on the ‘second nature’ of their knowledges. Nothing depletes capital more than the sight of someone trying too hard. For example, fledgeling clubbers of fifteen or sixteen wishing to get into what they perceive as a sophisticated dance club will often reveal their inexperience by over-dressing or confusing ‘coolness’ with an exaggerated cold blank stare.

It has been argued that what ultimately defines cultural capital as capital is its ‘convertibility’ into economic capital (Garnham and Williams 1986: 123). While subcultural capital may not convert into economic capital with the same ease or financial reward as cultural capital, a variety of occupations and incomes can be gained as result of ‘hipness’. DJs, club organizers, clothes designers, music and style journalists and various record industry professionals all make a living from their subcultural capital. Moreover, within club cultures, people in these professions often enjoy a lot of respect not only because of their high volume of subcultural capital, but also from their role in defining and creating it. In knowing, owning and playing the music, DJs, in particular, are sometimes positioned as the masters of the scene, although they can be overshadowed by club organisers whose job it is to know who’s who and gather the right crowd.

Although it converts into economic capital, subcultural capital is not as class-bound as cultural capital. This is not to say that class is irrelevant, simply that it does not correlate in any one-to-one way with levels of youthful subcultural capital. In fact, class is wilfully obfuscated by subcultural distinctions. For instance, it is not uncommon for public-school-educated youth to adopt working-class accents during their clubbing years. Subcultural capitals fuel rebellion against, or rather escape from, the trappings of parental class. The assertion of subcultural distinction relies, in part, on a fantasy of classlessness. This may be one reason why music is the cultural form privileged within youth’s subcultural worlds. Age is the most significant demographic when it comes to taste in music, to the extent that playing music in the family home is the most common source of generational conflict (after arguments over the clothes that sons and daughters choose to wear) (cf. Euromonitor 1989b). In contrast the relation between class and musical taste is much more difficult to chart. The most clearly up-market genre, classical music, is also the least disliked of all types of music by most sectors of the population, hence its abundant use in television commercials to advertise products of all kinds, from butter and baked beans to BMWs.

One reason why subcultural capital clouds class backgrounds is that it has long defined itself as extra-curricular, as knowledge one cannot learn in school.* As a result, after age, the social difference along which it is aligned most systematically is, in fact, gender. On average, girls invest more of their time and identity in doing well at school. Boys, by contrast, spend more time with (and money on) leisure activities such as going out, listening to records and reading music magazines (Mintel 1988c; Euromonitor 1989b). But this doesn’t mean that girls do not participate in the economy of subcultural capital. On the contrary, if girls opt out of the game of ‘hipness’, they will often defend their tastes (particularly their taste for pop music) with expressions like ‘It’s crap but I like it’. In so doing, they acknowledge the subcultural hierarchy and accept their lowly position within it. If, on the other hand, they refuse this defeatism, female clubbers and ravers are usually careful to distance themselves from the degraded pop culture of ‘Sharon and Tracy’. (This is a long story which is explored in chapter 3 on the feminization of the mainstream.)

A critical difference between subcultural capital (as I explore it) and cultural capital (as Bourdieu develops it) is that the media are a primary factor governing the circulation of the former. Several writers have remarked upon the absence of television and radio from Bourdieu’s theories of cultural hierarchy (cf. Frow 1987; Garnham 1993). Another scholar has argued that they are absent from his schema because ‘the cultural distinctions of particular taste publics collapse in the common cultural domain of broadcasting’ (Scannell 1989: 155). I would argue that it is impossible to understand the distinctions of youth cultures without some systematic investigation of their media consumption. For, within the economy of subcultural capital, the media are not simply another symbolic good or marker of distinction (which is the way Bourdieu describes films and newspapers vis-à-vis cultural capital), but a network crucial to the definition and distribution of cultural knowledge. In other words, the difference between being in or out of fashion, high or low in subcultural capital, correlates in complex ways with degrees of media coverage, creation and exposure.

The idea that concern for cultural value and status is common in popular cultures seemingly devoid of them is one which, once stated, seems obvious. However, the many ramifications of the idea are less clear and little explored. This book contributes to the shift away from stale celebrations to more critical analyses of popular culture. A great deal of extant research on youth subcultures has both over-politicized their leisure and at the same time ignored the subtle relations of power at play within them. This inquiry into subcultural distinctions – which concentrates on the three problems of the persistent value of authenticity, the useful myth of the mainstream and the symbiotic relations between cultural kudos and the media – attempts to give fuller representation to the complex politics of popular culture.

Youth and their Social Spaces

Why are discotheques, particularly their recent incarnations as clubs and raves*, so central to British youth culture? How do dance clubs fit into the larger context of youth’s social spaces and leisure activities? What exactly are the appeals of the institution? How do they fulfil youth’s cultural agendas? The following social geography of youth goes some way towards explaining the existence of club cultures. It maps the empirical terrain upon which dance cultures rest as a necessary preface to an analysis of their distinctions.

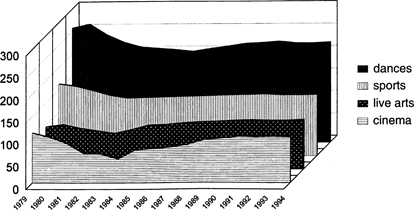

Because clubbing and raving are done by a narrow segment of the population after most other people have gone to bed, the scale of the social phenomenon often goes unnoticed. Admissions to dance events are substantially higher than those to sporting events, cinemas and all the ‘live’ arts combined. In financial terms, the value of the club market (called ‘nightclubs’ by the leisure industry to avoid the fashion connotations of words like ‘club’ or ‘rave’ and to convince shareholders that such establishments are a stable investment) was estimated as being £1,968 million in 1992 (Mintel 1992). Although data on raves is even more in the realm of the ‘guesstimate’, the value of the rave market was calculated to be £1.8 billion ($2.7b) in 1993. A survey by the Henley Centre for Forecasting found that attendance at rave events was over fifty million a year in Britain, with each person spending an average of £35 ($52) on admission charges, soft drinks and recreational drugs (Music and Copyright 10 November 1993).

Figure 1 Dance versus other entertainments 1979–94 (million admissions) (Source: Leisure Consultants)

Going out dancing crosses boundaries of class, race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality, but not differences of age. The most avid clubbers and ravers are between fifteen and nineteen, followed by those aged twenty to twenty-four. The age boundaries of clubbing are tight, framed on the younger end of the scale by practical factors such as being allowed out of the house after eleven, having enough money to pay the substantial entrance fees, and successfully negotiating a loosely enforced drinking age of eighteen. A loss of interest in clubbing coincides with moving out of the parental home, which has repercussions for young people’s desire to get out of the house and escape the family. Most importantly, however, clubbing declines when people form partnerships by either living together or marrying. Market research repeatedly finds that single people are ten times more likely to be frequent clubbers than married people (Mintel 1990 and 1992).

For a broad spectrum of British youth, then, going to dance clubs is an integral part of growing up. It is a rite of passage which marks adolescent independence with the freedom to stay out late with friends beyond the neighbourhood in a space which is relatively their own. Clubs allow their patrons to indulge in the ‘adult’ activities of flirtation, sex, drink and drugs, and explore cultural forms (like music and clothes) which confer autonomous and distinct identities.

The widespread significance of dance clubs to growing up may be unique to Britain. In America, bars and clubs are important to the gay rite of passage called ‘coming out’, but are peripheral to heterosexual adolescence. In so-called ‘Middle America’ (i.e. straight, white suburbia), acquiring a driver’s licence and access to a car offer the sense of freedom, mobility and independence that British youth find at clubs and raves. In Britain, fewer young people have a driver’s licence, let alone a car. ‘Joyriding’, which was subject to ‘moral panic’ in America in the 1950s, was considered a ‘new’ juvenile crime in Britain in the 1990s. Although car ownership is on the increase* (and ravers are dependent on cars to the extent that the events sometimes take place in remote areas of the countryside), British youth have yet to participate fully in American-style ‘driving’ or ‘parking culture’. The illicit activities of the back seat are vicariously understood from Hollywood films and American song lyrics, rather than from common personal experience.

This marginal position of the car is something that British youth cultures (in general) share with American youth cultures of the inner city (in particular). In fact, in older American cities with a surviving centre and a public transport system like New York, the dance club scenes are analogous to those of Britain. Edith Folb argues, however, that cars are a potent symbol even for American youth from low income backgrounds for whom cars are a luxury. In Afro-American youth culture, for example, cars ‘not only afford mobility and prestige, but they become total environments to themselves. They are literally like mobile homes.’ This is accentuated by the practice of ‘freaking off cars, in other words, fixing them up and lavishly decorating their interiors (Folb 1980: 84).

One can make a parallel between cars and clubs in their respective national contexts. The centrality of the car to American leisure is the main reason behind a strictly enforced legal drinking age of twenty-one. Conversely, in Britain, the drinking age of eighteen is seldom enforced – partly because British lawmakers haven’t needed to worry about commensurate road fatalities. As a result, by the age it is legal to go to clubs in the United States, youth in the United Kingdom have started to lose interest in the activity.

Just as British youth have less access to the ‘home away from home’ of the car, so they enjoy less personal space within the home itself. Britain has a lower standard of living and a higher population density. Even with the decline in family sizes, overcrowding is still standard. Moreover, due to a decline in the average youth wage and to the increased participation of youth in education or training, a greater number of young people have had to delay ‘leaving home’ (cf. Smith 1992). Although the campus (with its residences, student unions, lounges, cafeterias and other semi-public spaces) is the cultural focus of a privileged but still substantial number of Americans, it has been and still is accessible to fewer Britons.* Moreover, even though there have been great increases in the number of students in higher education, most of the new universities do not have campuses in the traditional sense and can ill afford to provide student-only space.

Not only is there limited cubic space, but the average British home enjoys less of the extensive if virtual social space afforded by the telephone. British youth are less likely to have their own extension, let alone their own line (which is becoming an upper-middle-class norm in the States) and, without that privacy, the phone is of limited social use. Moreover, because one has traditionally paid by the minute for local calls, the kind of social life where one spends hours talking to friends has been prohibitively expensive for all but the most affluent. For this reason, young people’s outgoing calls tend to be strictly regulated by their parents (cf. Silverstone and Morley 1990).

Youth often seek independence from the ‘tyranny of the home’ through their management of time (cf. Douglas 1991). Synchrony is crucial to the order and integration of the home. Youth therefore often adopt ‘anti-social’ strategies of time-use such as schedules whereby they stay up late and wake up late to avoid parental scrutiny and control. Domesticity is anathema to many youth cultures. It is not surprising, then, that youth watch less of that domestic medium, television, than any other age-group except newborn babies (cf. BBC Broadcasting Research 1990). Moreover, youth television programming follows this logic of de-synchronization. Many youth-orientated shows are scheduled before and after prime time partly because, in single television households, youth can then watch alone, but also because youth are likely to be out in the middle of the evening. In fact, youth’s absence from the home has led satellite services like MTV Europe to argue that ratings should take into account out-of-home viewing in pubs and cafés which they have tried to promote to potential advertisers as the ‘O.O.H. factor’ (cf. Broadcast 14 May 1993).

British youth spend considerable time on the street. By night, young people often congregate outside pubs and clubs, and around hubs of public transportation. In fact, because late-night buses are intermittent and tend to leave from a single square in the city centre, after-hours scenes develop at bus shelters where vendors sell hotdogs to youth on their way home under the surveillance of police, bus and taxi drivers. Eating out for British youth has long meant eating on the street, for high streets have been more likely to have fish-and-chip and kebab take-aways than sit-down fast-food restaurants. This too relates to the high cost of space. Outdoor shopping is also a norm. Youth-oriented shopping streets (like Carnaby Street and parts of the King’s Road) and weekend clothes markets (like Camden Town, said to be the largest street market in Europe) are places for the spectacular congregation of subcultural youth. But limited opening hours mean that these are daytime territories. The indoor malls, vital to the assembly of American youth, are relatively few and far between. Moreover, most close at 5.30 p.m. and are consequently less significant to British youth culture.

Young people go to more films than any other age-group, but the cinema is not central to the distinct culture of British youth (cf. Docherty et al. 1987). Jon Lewis asserts that films are the ‘principal mass mediated discourse of youth’ and positions rock’n’roll as a ‘corollary narrative’ (Lewis 1992: 2–3). This may have been true of British youth culture in the 1950s, but it is certainly not the case in the 1990s. The cinema is a significant option for an evening’s entertainment, but it only occasionally prevails over youth styles, tastes and activities outside screen time. In the United States, movies are probably more central to youth culture, first, because rates of cinema-going are higher and, second, because Hollywood depicts American youth (cf. Austin 1989). The much less prolific British film industry, however, concentrates on literary adaptations, period and ‘art’ films rather than ‘teenpics’ and, as a result, portrays British youth only sporadically and then generally in an historical setting (e.g. Absolute Beginners and Young Soul Rebels).

The cultural form closest to the lives of the majority of British youth is, in fact, music. Youth subcultures tend to be music subcultures. Youth buy more CDs and tapes and listen to more recorded music than anyone else. Youth television is to a large extent music television, while young men’s magazines are predominantly music magazines. Youth leisure and identity often revolve around music. Even market research repeatedly finds that ‘young adults are under a certain amount of peer pressure to keep abreast of trends in modern music which forms an important part of their active socializing with people of the same age group attending concerts, dances, pubs, clubs and raves’ (Mintel 1993).

One of the main ways in which youth carve out virtual, and claim actual, space is by filling it with their music. Walls of sound are used to block out the clatter of family and flatmates, to seclude the private space of the bedroom with records and radio and even to isolate ‘head space’ with personal stereos like the Walkman. The Walkman often affords a feeling of autonomy and empowerment by cutting the wearers off from unwanted communication and distancing them from their surroundings (cf. Hosokawa 1984). For this reason, portable personal stereos are used mainly by young people: 40 per cent of 15–19-year-olds and 22 per cent of 20–24-year-olds listen to Walkmans, compared to only 5 per cent of those over 35 (Mintel 1993).

Conversely, adults can get rid of young people by playing music that grates on their taste. For example, in an attempt to deter teenagers from hanging-out in their stores, the American 7-Eleven chain began playing ‘easy listening’ music from loudspeakers outside their shops. Having experimented with many tactics, they found this method to be most effective. ‘It really worked well,’ said a spokeswoman, ‘the kids found it was uncool to be anywhere near that kind of elevator music’ (The Guardian 27 August 1990). Youth tend to have specialist music tastes, with strong preferences for hiphop, indie or hardcore dance. Less than a third of 15–24-year-olds say they really like ‘pop’, which is not surprising given that it is the overwhelming favourite of children and pre-teens between eight and fourteen (Euromonitor 1989).

As meeting people is a prime motivation behind youthful leisure activities, however, communal listening is still paramount. Previously British youth subcultures might have found their consummate expression in ‘live’ music events. Although ‘live’ events still thrive in relation to certain genres, since punk, increasing numbers of British youth cultures have revolved around records rather than performance. This has a complicated history which is recounted in the next chapter. Suffice it to say here that the long-term decline of ‘live’ music and the slow rise of the discotheque in its many incarnations from record hops to raves has led to a situation whereby the majority of British music cultures could be described as disc cultures.

Comparison with that quintessentially British institution, the public house or pub, is particularly revealing about the appeal of dance clubs. Although young people go to pubs more often than any other place outside the home, pubs have not accrued the same symbolic or social significance as clubs and raves (cf. Mintel 1990). The reasons are manifold. Firstly, there is a simple legal determinant. Since 1953, having a dancefloor of a certain size specification has been the cheapest and surest way to acquire the music and dancing licence that has rendered premises eligible for a late liquor licence. As a result, dance clubs are one of the few spaces open when the pubs close at 11 p.m. in England and Wales and midnight in Scotland.

Alcohol is the most widely used intoxicant of club cultures, if only because it is legal, easily available and inexpensive.* However, ‘uppers’ like speed and cocaine have long been club drugs, while Ecstasy (sometimes pharmaceutical MDMA, often a cocktail of amphetamines and LSD) was the prototypical drug of the late-eighties/nineties rave scene. Research shows that many clubbers are often polydrug users who tend to abstain from drugs other than marijuana outside clubs and raves (cf. Newcombe 1992). Much like the hippie cultures that Jock Young analysed in the late sixties, it would seem that legal drugs like alcohol are used by clubbers to ‘symbolize the achievement of adult status’, while illicit drugs are used to signify a rejection of adult culture (Young 1971: 147).

A second reason for the popularity of clubs over pubs is that the latter are continuous with their locality and tend to use the cosy decorative rhetoric of the home (often the Victorian home). Clubs, however, offer other-worldly environments in which to escape; they act as interior havens with such presence that the dancers forget local time and place and sometimes even participate in an imaginary global village of dance sounds. Clubs achieve these effects with loud music, distracting interior design and lighting effects. British clubs rarely have windows through which to look into or out of the club. Classically, they have long winding corridors punctuated by a series of thresholds which separate inside from outside, private from public, the dictates of dance abandon from the routine rules of school, work and parental home.

In fact, so powerful are the feelings of ‘liberation’ afforded by the dance club that the most common argument about contemporary social dancing is that it empowers girls and women (cf. Blum 1966, Rust 1969, McRobbie 1984, Griffiths 1988, Gotfrit 1988). However, these studies tend to conflate the feeling of freedom fostered by the discotheque environment with substantive political rights and freedoms. Youthful discourses about clubbing and raving themselves promote this confusion. The lyrics of dance tracks, which raid the speeches of political figures like Martin Luther King and feature female vocalists singing ‘I got the power’ and ‘I feel free’, work to blur the boundaries between affective and political freedom. However, one shouldn’t forget that these records tend to be segued between tracks which incite the dancer to ‘let the music take control’ or recommend that their ultimate goal should be ‘total ecstasy’.

A third cause behind the preference for clubs over pubs is that the latter tend to cross age and style boundaries, whereas clubs target youth and keep up with their fads and fashions by frequently changing their music playlists, decor and names. Their adaptability is facilitated by the distinction between ‘clubs’, which operate on one night of the week, and their ‘venues’, the licence-holding architectural spaces which they inhabit. By these means, permanent venues attempt to cope with fast-changing fashions, try to avoid identification with any particular scene, prolong their life and defer costly refurbishment.

When raves moved clubs out of traditional dance venues into new sites like disused warehouses, aircraft hangars, municipal pools and tents in farmers’ fields, it was partly in pursuit of forbidden and unpredictable senses of place. An organizer of clubs and raves explains the distinction as he perceives it:

The difference between a rave and a club is the same as [that] between a holiday resort that no one goes to – you’ve discovered this beautiful place – and going back five years later to find they’ve built twenty-five high-rise hotels along the beach. Raves explore new territory, while clubs are the same old predictable places. (Leo Paskin, interview: 19 March 1993)

Finally, in addition to having the advantages mentioned above, clubs facilitate the congregation of people with like tastes – be they musical, sartorial or sexual. Clubs have larger catchment areas, narrower demographics and taste specializations than pubs. Through the use of flyers, listings, telephone lines and flyposting, club organizers aim to deliver a particular crowd to a specified venue on a given night. To a large degree, then, club crowds come pre-sorted and pre-selected. The door policies which sometimes restrict entry are simply a last measure. If access to information about the club and taste in music fail to segregate the crowd, the bouncers will ensure the semi-private nature of these public spaces by refusing admission to ‘those who don’t belong’.

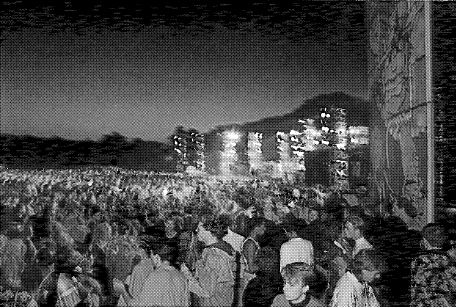

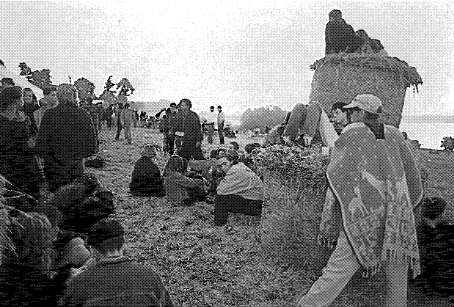

Plates 1 and 2 Two ‘mould-breaking’ raves held just ten miles apart on 26–7 August 1989. (1) Five thousand ravers at World Dance party just before sunrise (2) A few hours later eight hundred clubbers greet the dawn at Boy’s Own party near East Grinstead.

(Photographs: David Swindells)

This institutional state of affairs is arguably the precondition for that oft-celebrated experience of social harmony, the thrill of belonging afforded by clubs. In other words, although some clubbers complain about the gatekeeping practices which assemble, construct and limit the crowd, these practices are undoubtedly a problematic part of their appeal. Moreover, discriminatory admission policies are actually recommended by many local governments as a means of crowd control (and clubs need to heed their suggestions if they want to maintain their licences). For example, the now defunct, left-wing Greater London Council was one of the few local governments actually to publish a code of practice for discotheques. Despite being much out-of-date, it is worth quoting here because of its explicitness:

The type of person admitted to discos determines the standard conduct on the premises and the likelihood of violence occurring. Licensees should have a clear policy on the sort of people they want to see on their premises. Steps should be taken to exclude anyone considered to be undesirable. Management can turn anyone away without explanation. If in doubt they should refuse entry.

Management should have a clear policy on the following:

- of dress permitted

- people at the door.

- there should be an equal balance of the sexes.

- drunks and other undesirables should be excluded.

- to keep a list of barred people.

- at which admission to the premises ends.

- to adopt a price policy to discourage people who have been drinking elsewhere from coming towards the end of the disco.

- to fix a minimum age of admission.

(GLC 1979: 5; my italics)

Clubs, by popular demand and government recommendation, segregate. This segregation is sometimes condemned for being elitist or racist. At other times it is celebrated for guaranteeing subcultural autonomy and permitting subordinate social groups to control and define their own cultural space. The latter proposition was theorized by subculturalists in the Birmingham tradition as a heroic ‘winning of space’ and resistant maintenance of subcultural boundaries. In Resistance Through Rituals, for example, Clarke et al. contend that subcultures ‘win space for the young: cultural space in the neighbourhood and institutions … actual room on the street or street corner. They serve to mark out and appropriate territory in the localities’ (Clarke et al. 1976: 46; my italics). While they identify space as an important social issue, there are at least two problems with this formulation. First, ideas of ‘winning’ and defiantly ‘appropriating’ mystify more than they reveal. To a large extent, places are ‘won’ when social groups are recognized as profitable markets. Venue owners hire club organizers (or club organizers hire venues) to target, promote and advertise to both ‘rebellious’ and ‘conforming’ youth. Crucially, in the case of dance clubs and raves, their marketing has been most successful when youth feel they have ‘won’ it for themselves. Second, discotheques may house alternative cultures, but they tend to duplicate structures of exclusion and stratification found elsewhere. Black men, in particular, find themselves barred or, more usually, subject to maximum quotas. This ongoing fact should not be forgotten in the face of the utopian ‘everybody welcome’ discourses in which dance clubs are intermittently enveloped. For example, despite their discourses of liberty, fraternity and harmony, raves had distinct demographics – chiefly white, working-class, heterosexual and dominated by the lads. Raves may have involved large numbers of people and they may have trespassed on new territories, finding new spaces for youthful leisure, but they did little to rearrange its social affairs.

As a semi-private, musical environment which adapts to diverse fashions, proffers escape (sometimes with added transgressional thrills) and regulates who’s in and who’s out of the crowd, the dance club fulfils many youth cultural agendas. Like youth subcultures themselves, the institution has developed since the Second World War and multiplied in kind and style since the seventies. In accommodating the social activities of a few fleeting years of youth, discotheques have become a lasting cultural establishment. However, the popularity of the discotheque was not automatic. For years, it was considered a second-rate institution, a lowly entertainment, a cheap night out. The next chapter considers the slow process by which the discotheque distinguished itself.