2

Authenticities from Record Hops to Raves (and the History of Disc Culture)

The Authentication of a Mass Medium

Authenticity is arguably the most important value ascribed to popular music. It is found in different kinds of music by diverse musicians, critics and fans, but it is rarely analysed and is persistently mystified. Music is perceived as authentic when it rings true or feels real, when it has credibility and comes across as genuine. In an age of endless representations and global mediation, the experience of musical authenticity is perceived as a cure both for alienation (because it offers feelings of community) and dissimulation (because it extends a sense of the really ‘real’). As such, it is valued as a balm for media fatigue and as an antidote to commercial hype. In sum, authenticity is to music what happy endings are to Hollywood cinema – the reassuring reward for suspending disbelief.

While authenticity is attributed to many different sounds, between the mid-fifties and mid-eighties, its main site was the live gig. In this period, ‘liveness’ dominated notions of authenticity. The essence or truth of music was located in its performance by musicians in front of an audience. Interestingly, the ascent of ‘liveness’ as a distinct musical value coincided with the decline of performance as both the dominant medium of music and the prototype for recording. Only when records began to be taken for music itself (rather than as ‘records’ in the strict sense of the word) did performed music really start to exploit the specificities of its ‘liveness’, emphasizing presence, visibility and spontaneity.

In fact, the demand for live gigs was arguably roused by the proliferation of recordings, which had the effect of intensifying the desire for the ‘original’ performer. Steve Connor contends that ‘increasingly high fidelity reproduction stimulates the itch for more, for closer reproductions, and the yearning to move closer to the original’ (Connor 1987: 130). Similarly, Andrew Goodwin argues that ‘aura’ has been transferred from the art object to its maker; it has taken up residence in the physical presence of the star (Goodwin 1990: 269). Walter Benjamin, the theorist who first explored this terrain in the 1930s, hoped that ‘the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction’ would be liberated from this kind of worship. He believed that the awe reserved for unique objects would decline in a democratized world of mass-produced cultural goods. However, he knew this process would be difficult, for ‘cult value does not give way without resistance’ and was even suspicious that it would ‘retire into an ultimate retrenchment: the human countenance’ (Benjamin 1955/1970: 227–8).

What Benjamin did not and could not foresee was the formation of new authenticities specific to recorded entertainment, for these were dependent on historical changes in the circumstances of both the production and consumption of music. Initially, records transcribed, reproduced, copied, represented, derived from and sounded like performances. But, as the composition of popular music increasingly took place in the studio rather than, say, off stage, records came to carry sounds and musics that neither originated in nor referred to actual performances. In the 1960s, with the increased use of magnetic tape, producers began to edit their wares into ‘records of ideal, not real, events’ (Frith 1987a: 65). Moreover, in the 1970s and 1980s, new instruments such as synthesizers and samplers meant that sounds were recorded from the start. Accordingly, the record shifted from being a secondary or derivative form to a primary, original one.

In the process of becoming originals, records accrued their own authenticities. Recording technologies did not, therefore, corrode or demystify ‘aura’ as much as disperse and re-locate it. Degrees of aura came to be attributed to new, exclusive and rare records. In becoming the source of sounds, records underwent the mystification usually reserved for unique art objects. Under these conditions, it would seem that the mass-produced cultural commodity is not necessarily imitative or artificial, but plausibly archetypal and authentic. These values are related to but different from the ‘mystical veil’ or ‘magic’ described by Marx in his short essay, ‘The fetishism of commodities and the secret thereof’. Commodity fetishism would seem to account accurately for the obsessions of record collectors who call themselves ‘vinyl junkies’, but it does not explain the inversion of original and copy.

The proliferation of ‘cover’ bands from the 1950s to the mid-1970s probably best demonstrates this transposition of values. These live groups reproduced the tunes of the latest hit records and were evaluated on the basis of their proximity to the original record, hence their choice of names like ‘Disc Doubles’ and ‘Personality Platters’. By the eighties, these types of rock and pop cover bands were all but defunct, being superseded for the most part by records and to a lesser extent by tribute bands which specialized in the repertoire of specific dead or disbanded acts. (For example, the Australian Abba imitators, Bjorn Again, who played more university gigs in Britain than any other live act in the 1992–93 academic year, emulate not just records but the clothing and dance styles depicted on album covers and in film and video clips.)

Changes in music consumption were also essential to the development of the new authenticities of the disc. Records were not automatically absorbed into a static system called popular culture. Nor did they simply replace performance just because they resembled and reproduced music. The public acceptance of records for dancing was slow, selective and generational. For many years, records were considered a form of entertainment inferior to performance; they were not regarded as the ‘real’ thing or as capable of delivering an authentic experience of musical community. Records had to undergo a complex process of assimilation or integration, which involved transformations in the circulation, structure, meaning and value of both records and music cultures. This gradual enculturation of records is signalled by the changing names of the institution in which people danced to discs. The record hops, disc sessions and discotheques of the 1950s and 1960s specifically refer to the recorded nature of their entertainment. In the 1970s, transition is signalled with the shortened, familiar disco. In the 1980s, with clubs and raves, enculturation is complete and it is ‘live’ venues that must announce their difference.

The ultimate end of a technology’s enculturation is authentication. In other words, a musical form is authentic when it is rendered essential to subculture or integral to community. Equally, technologies are naturalized by enculturation. At first, new technologies seem foreign, artificial, inauthentic. Once absorbed into culture, they seem indigenous and organic. Simon Frith has been most productive in analysing the discourses of subcultural authenticity crucial to music culture (cf. Frith 1981c, 1986, 1988a). Frith argues that new music technologies tend to be opposed to nature and community. They are considered false and falsifying and, as such, threaten the authenticity or the ‘truth of music’ (Frith 1986: 265). Behind the discursive oppositions, however, lurks the fact that technological developments make new concepts of authenticity possible. In the early days of the microphone, for example, crooners were said to have a pseudo-public presence and to betray false emotions. Later, however, the extended intimacies of the microphone became a guarantor of new forms of authenticity; ‘it made stars knowable, by shifting conventions of personality, making singers sound sexy in new ways … moving the focus from the song to the singer’ (Frith 1986: 270). Similarly, when electric guitars were first introduced, they were said to alienate music from its folk roots. Later, however, when they were fully integrated into rock culture, the sound of the electric guitar became the seal of rock credibility. Records have taken an analogous, if more circuitous route, to become an authentic musical instrument of club and rave culture.

In the 1990s, records have been enculturated within the night life of British dance clubs to the extent that it makes sense to talk about disc cultures whose values are markedly different from those of live music cultures. What authenticates contemporary dance cultures is the buzz or energy which results from the interaction of records, DJ and crowd. ‘Liveness’ is displaced from the stage to the dancefloor, from the worship of the performer to a veneration of ‘atmosphere’ or ‘vibe’. The DJ and dancers share the spotlight as de facto performers; the crowd becomes a self-conscious cultural phenomenon – one which generates moods immune to reproduction, for which you have to be there. This is even more pronounced when it comes to raves, the latest incarnation of the discotheque, which are conceived as one-off rather than weekly events, some of which have attained the status of unique happenings on a scale that was once the lone preserve of the live rock festival.

Subcultural authenticities are often inflected by issues of nation, race and ethnicity. Gage Averill examines the significance of being ‘natif natal’ or native born and truly national to the perceived authenticity of Haitian music (cf. Averill 1989). While Paul Gilroy considers the trans-Atlantic circulation of discourses about racial roots and ‘authentic blackness’ to the meaning of post-war popular music (cf. Gilroy 1993). So, black British disc cultures often emphasize the strength of community ties outside the dance club, seeing the ‘vibe’ as an affirmation of a politicized black identity. Sexuality similarly informs and inflects disc cultural values. In gay clubs, which have long been spaces to escape straight surveillance, the celebratory expression of one’s ‘true’ sexuality often overrides other authenticities.

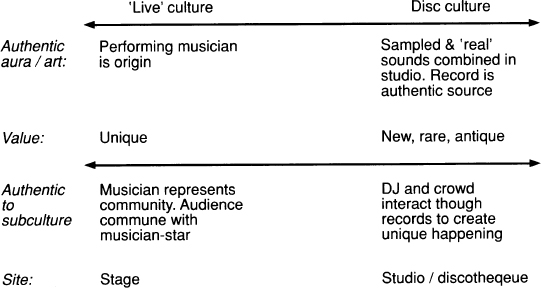

Between the production and consumption of records discussed here, two kinds of authenticity are at play. The first sort of authenticity involves issues of originality and aura; this value is held most strongly by DJs. The second kind of authenticity is about being natural to the community or organic to subculture; this is the more widespread ideal. These two kinds of authenticity can be related to two basic definitions of culture: the first draws upon definitions of culture as art, the second relates to culture in the anthropological sense of a ‘whole way of life’ (cf. Williams 1961 and 1976). With live music ideologies, the artistic and subcultural authenticities collide (and are often confused) at the point of authorship. Artistic authenticity is anchored by the performing author in so far as s/he is assumed to be the unique origin of the sound, while subcultural authenticity is grounded in the performer in so far as s/he represents the community. Within disc cultures, however, the two authenticities diverge. The record is an authentic source and the crowd makes it a ‘living’ culture. DJs bridge the gap in that they are professional collectors and players of ‘originals’ as well as mediators and orchestrators of the crowd, but not to the extent that they seem to embody authenticity (like live music performers).

Live and disc authenticities, though distinct, still have a lot in common. Both emphasize the cultural importance of being genuine and sincere and both seek to elevate their cultures above the realm of mass culture, media and commerce. Moreover, much popular music is entangled with both sets of values. Bands like the Rolling Stones are caught up in the logic of disc culture even if the dominant strains of their myth are about Mick Jagger as dramatic performer, Keith Richards as virtuoso guitarist and a legacy of gigging and live stadium shows. Similarly, even hardcore disc cultures, like house or techno, sometimes espouse residual variants of live ideology, celebrating star producer-DJs and singing divas. Some clubs and raves include ‘personal appearances’ (or ‘PAs’) by these dance ‘stars’, while others have made a purist selling point of the fact that they have ‘no PAs’. Live and recorded authenticities are therefore not mutually exclusive categories, but part of a continuum.

The development of disc cultures, the enculturation of records for dancing and the cultural ramifications of the supremacy of recording are the key issues addressed in this chapter. Most academic work on recording technology examines its effects on music production, in either its industrial or artistic guise. The main currents of debate consider whether it is democratizing or hierarchizing, rationalizing or disruptive of production processes, commodifying or challenging to legal definitions of property, inhibiting or enabling of new creativities and sites of authorship.* While this chapter touches upon these issues, it concentrates on the less investigated relationship between recording technology and consumption.

The following chapter is divided into five sections, each of which recounts the history of the enculturation and ultimate authentication of records from a different angle. The first section is a political economy (an analysis of the production of music consumption) which traces the economically-determined routes by which records entered the field of popular entertainments, tracking the rise of records and decline of performance in certain kinds of time and place. It also considers the obstacles put in the path of this ‘industrial revolution’ by the Musicians’ Union, with its exploitation of rights’ legislation and campaign to keep music live’.

The rest of the chapter considers the integration of records into music culture from more social and cultural perspectives. The second section examines how the social spaces of dancing changed to accommodate recorded music. It considers how the new social alliances and architectural designs contributed to the eventual subcultural authenticity of records. The third focuses on how record formats were modified in response to their increasing public use, detailing the formatting experiments of the 1960s, the development of twelve-inch singles in the 1970s and finally concentrating on the changing status of the DJ. The fourth section explores the specificities of recording and the kinds of music most at home with the medium. It considers how changes in the way popular music was recorded and disseminated contributed to transformations in the meaning and value of records and ponders why certain music genres came to be perceived as quintessentially and authentically recorded while others did not. The final section looks at changes to the shape and meaning of the live gig during the period in question. It identifies two seemingly contradictory tendencies. On the one hand, performances increasingly exploit those features which might distinguish them from records, retrieving spontaneity, making a theatrical happening, magnifying the presence and personality of the star. On the other hand, many performers adopted high technologies, pre-recording and even lip-synching to entertain the massive audiences they had accumulated through records, radio and other media.

Until recently, media scholars tended to overlook enculturation. Marshall McLuhan, for instance, does not identify the process per se because he sees media technologies as already cybernetic ‘extensions of man’. His analysis starts with the natural and human qualities attributed to technologies once they are fully enculturated, but doesn’t problematize them (cf. McLuhan 1964). Jean Baudrillard, to give another example, ignores the distinct statuses and effects of techniques of reproduction because he assumes that technologies which simulate are not in need of any form of assimilation. Although well-known in anthropology, the issue of enculturation is relatively new to Media Studies, having been put on the agenda by the collection, Consuming Technologies, which addresses the integration of media and information technologies into the home (cf. Silverstone and Hirsch 1992). In their opening essay, Silverstone, Hirsch and Morley identify four overlapping phases in the process of a technology’s integration into the home: appropriation (by ownership); objectification (within the decorative space of the home); incorporation (into the temporal structure of everyday lives); and conversion (into topics of conversation and cultural bonds) (cf. Silverstone et al. 1992). These categories can be used, by analogy, to clarify important dynamics in the enculturation of records into the public sphere of dancing. For example, I examine something akin to ‘incorporation’ into temporal structures (in discussing the development of new kinds of dance event) and ‘objectification’ in spatial structures (in relation to the interior design of discotheques). Moreover, their category of ‘conversion’ is an important dimension of what I include under the more encompassing historical but more specifically aesthetic category of ‘authentication’.

One needs to be wary of superimposing models generated by study of domestic contexts on to the public domain, particularly in light of the fact that one of the main hypotheses about recording technology is that it necessarily privatizes or domesticates music consumption. In his book The Recording Angel, for example, Evan Eisenberg reduces his otherwise compelling argument about the art of ‘phonography’ because, for him, ‘a record is heard in the home’ and its tendency is essentially private (Eisenberg 1987: 99). Shuhei Hosokawa’s discussion of the Walkman, for another example, slips into positioning the personal stereo as the culmination of recording’s relentless logic of individuation (cf. Hosokawa 1984). By ignoring broader contexts, these theorists fail to see the contradictory effects of music technology and the diverse significance of recorded music. Recorded music is as much a feature of public houses, shops, factories, lifts, restaurants and karaoke bars as it is an attribute of the private home.

Another hypothesis against which this chapter offers substantial evidence is that records engender cultural homogeneity. Recording technology informed Theodor Adorno’s conviction that popular music was characterized by a standardization that aimed at standard reactions (Adorno 1968/1988). While disciples of Adorno, like Jacques Attali, continue to contend that mass-reproduced music is ‘a powerful factor in consumer integration, interclass levelling, cultural homogenization. It becomes a factor in centralization, cultural normalization, and the disappearance of distinctive cultures’ (Attali 1985: 111). However, the discotheque is an institution which caters for neither individual nor mass consumption, but the collective consumption of the small group. Rather than homogenizing tastes, dance clubs nurture cultural segmentation.

Authenticity is regularly mentioned in studies of popular music but (other than the studies already cited) it tends to be discussed in terms of nebulous free-floating beliefs. Even when it is subject to thorough examination, it can still be indeterminate and unanchored. But these cryptic cultural values have material foundations; they relate to the economic, social, cultural and media conditions in which they were generated. The main aim of this chapter is, therefore, to ground the changing values of authenticity in transformed processes of music production and consumption.

Industrial Forces, Musician Resistance and ‘Live’ Ideology

Records were selectively enculturated into music culture: they moved from the private to the public sphere, from background accompaniment to specially featured entertainment, from minor occasions to momentous events, from modest locations to prominent places. Their movement is partly explained by an economic logic by which they replaced performance in the times and places with the youngest patrons and lowest budgets. Their progressive colonization of public spaces, however, was actively fought by the Musicians’ Union which was the first (and for a long time the only) body to see the practice as a serious cultural development. At the outset, the Union wanted to eradicate the practice; then it was satisfied with regulating it; later, it was appeased by receiving a percentage of the millions of pounds accrued in performance rights; finally, it resigned itself to the fact that recorded music was what many people wanted. Throughout this forty-year period, however, the Union reinforced its legislative efforts with ‘propaganda’ about the superiority and authenticity of live music. Where live music used to animate social occasions and cultural events of all kinds, recorded music now often performs the function. As a result, musician performances have declined in number, and appeal to a much smaller segment of the population than they once did.

When sound recording technology was introduced in the late 1870s, Thomas Edison proposed many uses for the new invention, few of which suggested its entertainment value. His recommendations revolved around the notion of a ‘talking machine’ which could facilitate dictation, record telephone messages, make books for the blind or create family albums for posterity (cf. Read and Welch 1976). Edison mentioned, but did not give much credence to, the phonograph’s potential as a ‘music box’. Within thirty years, however, music would be the staple noise of recording. Dance crazes, in particular, stimulated the early record business and repeatedly revived it in times of recession. In the 1910s, for example, dance instructors like Vernon and Irene Castle were important advisers to record company Artist and Repertoire departments (known as ‘A&R’, the division which decides who to sign and what material to record). They supervised records catering to the mania for tangos, one-steps, waltzes and walking dances. Even on the eve of the First World War in 1914, Columbia’s and Victor’s dance cylinders and discs were selling well (Gelatt 1977: 189).

From its inception, then, one of the main activities of the record industry was the provision of music for dancing, but it was mainly devised for home consumption, for practising dance steps and throwing parties in the private sphere. Throughout the 1920s, sound quality improved, particularly as a result of the introduction of electrical recording. This, combined with the increasing variety of musical material, singers and orchestras offered on record, made the medium more attractive. In the United States, the public performance of records on coin-operated phonographs or ‘juke-boxes’ kept the industry afloat when domestic sales dried up during the Depression. To ‘juke’ or ‘jook’ is an Afro-American vernacular expression meaning ‘to dance’ (cf. Hazzard-Gordon 1990). That the coin-operated phonograph took this name illustrates the importance of dancing to American out-of-home record-play at this time. In the UK, however, where the Depression took a different form, the juke-box did not significantly penetrate the public sphere until the fifties and sixties, and recordings did not tend to be an attracting feature of out-of-home entertainment.

During the twenties, radio quickly became a dominant source of music, most of which was broadcast live. The most popular programmes featured big dance bands who played for an audience of ballroom dancers at the same time as playing for those at home (cf. Frith 1987a). Record companies saw radio as a problem of competition and so did not send their recordings to stations for promotional purposes. When the first BBC radio programme devoted to records began in July 1927, however, its impact on sales was so obvious that record companies began to actively pursue air-play to the extent of buying plays on commercial continental stations like Radio Luxembourg. By the 1930s, argues Frith, radio was central to the new processes of record-selling and star-making which came with the shift in the commodity status of music:

The form of that commodity was irrevocably altered from live to recorded performance, from sheet music to disc, from public appearance to public broadcast – and its control passed from one set of institutions (music publishers, music hall and concert promoters, artists and agents) to another (record companies, the BBC, stars and managers). (Frith 1987a: 288)

While it is undeniable that recording took over from publishing as the leading arbiter of musical taste and style, some qualification is required of a historical shift ‘from public appearance to public broadcast’. Radio unseated the primacy of the family piano rather than challenging the dance hall; it rearranged domestic consumption (in a way the gramophone had not done) rather than instigating a massive withdrawal into the home.

During the thirties, recorded music was peripheral to out-of-home entertainment with one crucial exception – the cinema. Before the ‘talkies’, a large portion of Britain’s professional musicians were employed to accompany silent films. But within eighteen months of the box-office success of The Jazz Singer (1927, the same year as the BBC’s first record show), most of these musicians were out of a job and performance had received its first great blow. The development was crucial for the record industry as movies would become a vehicle for the international promotion of records. In the fifties, for example, the cinema would bring rock’n’roll attitudes and music to Britain with the film Blackboard Jungle and its closing track ‘Rock around the Clock’ by Bill Haley and the Comets. By the late fifties, the mutual marketing of movies and discs would be so entrenched that the album charts would be full of film soundtracks. As 45 singles were the format bought by youth in the fifties, the soundtrack albums were not predominantly rock’n’roll. The biggest sellers – South Pacific (1948), Love Me or Leave Me (1955), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1962) and The Sound of Music (1960) – still tended towards ‘family entertainment’. In the sixties, a fair portion of both Elvis Presley’s and the Beatles’ albums were marketed as ‘original soundtracks’ e.g. Elvis’s GI Blues (1960) and Blue Hawaii (1961), the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help (1965). By the end of the sixties, the best-selling soundtracks would also be youth-oriented owing to the juvenilization of film audiences (cf. Doherty 1988). and the rising popularity of the album format amongst youth. The success of Simon and Garfunkel’s sound track for The Graduate in 1968 might be seen as the turning-point here.

Aside from cinemas, recorded music could be heard in pubs, restaurants and coffee bars. As early as the 1930s, the record industry began to take a financial interest in the public performance of its product. The Copyright Act of 1911 was regarded as protecting manufacturers against the unauthorized copying, as opposed to playing, of their sounds; it established a reproduction, but not a performance, right. Nevertheless, in the early thirties, record companies started to affix labels stating that the record should not be publicly performed and in 1934 they sued Cawardine’s Tea Rooms in Bristol for copyright infringement, winning the rights to the sound contained in their recordings, and set up Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL) to license the broadcast and public performance of their records.

Until the Second World War, records tended to provide background accompaniment to leisure activities; they were rarely the main entertainment at large public events. Owing in part to further improvements in technology, but primarily to the devastated condition of the British economy, the public performance of records increased dramatically during and after the War. The Musicians’ Union (MU) was particularly concerned about the use of records for dancing as the bulk of its membership worked in dance bands. In 1949, the cover of its in-house journal, Musicians’ Union Report, bore the watchwords ‘Recorded Music or You!’ and inside the Secretary General warned:

Probably the greatest threat from recorded music to the employment opportunities of our members exists in the field of casual dance engagements. There is abundant evidence that in recent years more and more dance promoters have availed themselves of the services of the public address engineer. In almost every town the man who runs the radio shop, or specializes in the provision of public address equipment, will undertake to supply recorded music for dances or other social events at a small proportion of the fee a good band would charge. (Musicians’ Union Report September-October 1949)

At about this time, the Musicians’ Union came to the first of many agreements with Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL) to attempt to combat the public use of records. As musicians were hired to perform by dancehall operators and to record by record companies, the Union was able to impede the use of records by the former through the exploitation of rights’s agreements with the latter. Since its formation, PPL had been authorizing the use of its records simply in exchange for a licence fee. From 1946 on, however, it began licensing establishments on the condition that ‘records not be used in substitution of a band or orchestra or in circumstances where it would be reasonable to claim that a band or orchestra should be employed.’ (Musicians’ Union Conference Report 1949).*

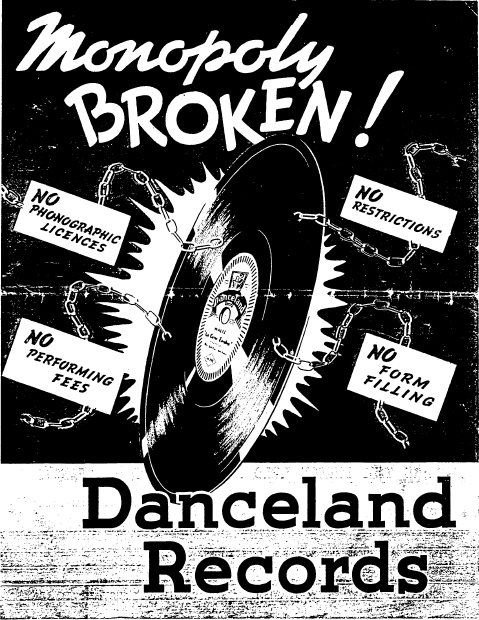

Licensing restrictions were the driving force behind one of the first examples of the production of records specifically for public dancing. In 1950–51, Danceland Records produced ballroom numbers in standard arrangements on 78s. The objective of their records was not to provide continuous music nor fill the dancefloor (which would be the case with later formats) but simply to circumvent existing copyright law. They advertised their records for use in ballrooms, hotels, theatres and skating rinks and urged proprietors of these establishments to join the fight against PPL licensing restrictions. (Musicians’ Union Report 1951). As their recording sessions were held in Mecca ballrooms, the MU suspected that the dancehall chain financed the project.

In 1956, a new Copyright Act clarified the properties of the recording. It re-enacted the rights given to the record companies, defining the copyright in sound recordings as distinct from the copyright in musical works,† and reiterated the three acts which required a PPL licence: making copies of records, playing them in public and broadcasting them. The Musicians’ Union was unhappy with the act for several reasons. First, the record companies maintained exclusive copyright and only volunteered royalties to the MU. Second, although it gave PPL the right to set up musician employment restrictions, it also established a tribunal to which users of copyright material (like broadcasters and dancehall owners) could protest. Third, the new Act permitted the free use of records ‘at any premises where persons reside or sleep’ as long as no special price was charged for admission and at non-profit clubs and societies whose main objectives were charitable, religious or educational (Musicians’ Union Report October 1956).

Plate 3 One of the first instances of records made specifically for the public dancefloor. In 1950 ‘Danceland Records’, allegedly payrolled by Mecca Ballrooms, advertised the sovereignty and savings that their releases afforded dancehall operators.

(Reproduced by kind permission of the Musicians’ Union)

Many dance clubs came to exploit these loopholes. For instance, the Whisky-a-Gogo in Wardour Street (which, in the 1980s, abbreviated its name to the WAG) claimed exemption from the licence fee on the grounds that the club was the headquarters of an international students’ association. The club’s solicitors drew up the charter of the so-called ‘Students’ United Social Association’ which included the following tongue-in-cheek objectives: ‘to promote opportunities for recreation, social intercourse and refreshment for foreign and English students … to advance … good international relations between young persons … to assist the promotion of social contacts for foreign students with English-speaking persons …’ (Musicians’ Union Report 1963).

Other small clubs dodged PPL licences or their conditions of use in a variety of ways. For example, the Saddle Room, once described as the ‘most fashionable discotheque in London’, full of people from the rag trade and ‘most noticeably, a great many fashion models’ was licensed by PPL on the condition that it hire a trio of musicians, but musicians never actually performed at the club (Melly 1970: 63). But, these individual cases were generally too difficult and expensive to prosecute, so the MU focused its attention on dancehall chains like Mecca and Top Rank where employment and licence fees could be gained en masse.

During the fifties, the Musicians’ Union started calling for a propaganda campaign against records which would attack their moral and aesthetic inferiority, draw on new notions of live music and strengthen its position with PPL. The term ‘live’ entered the lexicon of music appreciation only in the fifties. As more and more of the music heard was recorded, however, records become synonymous with music itself. It was only music’s marginalized other – performance – which had to speak its difference with a qualifying adjective.

At first, the word ‘live’ was short for ‘living’ and modified ‘musicians’ as in the following passage: ‘during and since the war, recorded music has been used more and more instead of “live” instrumentalists’ (Musicians’ Union Report 1949). Later it referred to music itself and quickly accumulated connotations which took it beyond the denotative meaning of performance. First, ‘live music’ affirmed that performance was not obsolete or exhausted, but full of energy and potential. Recorded music, by contrast, was dead, a decapitated ‘music without musicians’ (Musicians’ Union Report 1956). Second, the term also asserted that performance was the ‘real live thing’. Liveness became the truth of music, the seeds of genuine culture. Records, by contrast, were false prophets of pseudo-culture.

Through a series of condensations, then, the expression ‘live music’ gave positive valuation to and became generic for performed music. It soaked up the aesthetic and ethical connotations of life-versus-death, human-versus-mechanical, creative-versus-imitative. Furthermore, Union discussions about live music were overlaid with a Cold War rhetoric typical of the time. Records were a ‘grave threat’, a ‘serious danger’ and an ‘ever-present menace’ to the livelihood of the musician. Recording technology was a bomb – a set of inventions which could bring about professional death: ‘The musician may well become extinct and music may cease to be written’ (Musicians’ Union Report 1961). The term ‘live’ suggested that performance was fragile in its vitality and in need of protection.

The ideology of ‘liveness’ was one of the Union’s principal strategies ‘to combat the menace’ of recorded music. The Union initiated its ‘live’ music campaign in the fifties, adopted the slogan ‘Keep Music Live’ in 1963 and appointed a full-time official to oversee the project in 1965. Invoking a difficult combination of aesthetic, environmental and trade union concerns, the campaign was meant ‘to convince the community of the essential human value of live performance’ and of ‘the social good [generated when] the public has more contact with the people who make music’ (The Musician August 1971; Music Week 7 January 1978).

It is tempting to draw parallels between the views of the Musicians’ Union and Jean Baudrillard’s treatises on hyperreality and the death of culture. For both, culture is dying on the altar of techniques of reproduction. For Baudrillard, images are the ‘murderers of their own model’ (Baudrillard 1983a: 10). For live music advocates, recording is slowly killing its original, performance: ‘technology can destroy music itself’ (The Musician 1963). Just as Baudrillard describes the ‘precession of simulacra’ as the creation of images that no longer reflect the real but engender it, so musicians complained about the ability of recording to make more sounds and styles than were physically possible for a band. Baudrillard and the Musicians’ Union held similar notions of real culture but, faced with its death, the French theorist chose to write its obituary, while the British Union lobbied for protective legislation and disseminated propaganda.

The Union’s promotion of live music was tangibly hampered by the musical taste (and anti-mass culture discourses) that predominated among its members. For a long time, many members refused to pander to ‘gimmick-ridden rock’n’roll rubbish’ and couldn’t understand why teenagers didn’t appreciate ‘good jazz’ (Musicians’ Union Report 1959). The exigencies of Union taste even allowed for musicians in ‘beat groups’ to receive lower rates of pay, as their agreements with Mecca and Rank referred only to ‘musicians employed by dance band leaders’ until well into the 1960s (Musicians’ Union Report January 1965). The American Federation of Musicians (AFM), which conducted a similar ‘Live Music’ campaign, seemed to be less caught up in a canon of good music. AFM local branches, for example, offered workshops to keep musicians up-to-date with latest dance music fads (like the Frug) and experimented with event formats (like ‘Live-o-theques’) (Billboard 24 April 1965). The British Union, however, did not just champion performance over recording, it tended to promote certain kinds of music over others. Their discourses and contractual agreements actually reinforced the ‘natural’ association of certain music genres, like rock’n’roll and later soul, with records.*

The ideology of live music was eventually adopted by rock culture (cf. Frith 1981a), becoming most strident in reaction to the attention disco music brought to discotheques in the mid-seventies, when tensions erupted into what was effectively a taste war. Discos were attacked for epitomizing the death of music culture. They were said to be artificial environments offering superficial and manufactured experiences: ‘a slick moving conveyor belt of the best product from the world’s rock factories, relayed by the finest amplification, with a deejay and lights to inject further doses of adrenalin’ (Melody Maker 30 August 1975). While the American ‘disco sucks’ discourse had evident homophobic and racist motivation (cf. Marsh 1985; Smucker 1980), British anti-disco sentiments are more directly derived from classist convictions about mindless masses and generational conflict about the poor taste of the young. This has to do with the disparate audiences with which the same music was affiliated in the two countries. In Britain, discotheques and disco music had a huge straight white working-class following and were not, as they were in the USA, strongly identified with gay, black and Hispanic minorities.

It is difficult to evaluate the effects of the ‘Keep Music Live’ campaign because, until well into the 1970s, musicians were preferred to records by most people anyway. In 1962, Kevin Donovan opened a discotheque called The Place in Hanley near Stoke-on-Trent. Although it had a capacity of five hundred, it received between ten and fifty patrons a night until Donovan started booking live bands. As the owner explains:

The good people of Stoke-on-Trent had decided there was no point in paying to hear records which were played on the wireless for nothing … We were taught our first major lesson in promotion – give the public what THEY want. If you want to advance your own ideas, these must be solidly hooked to an established and accepted aspect in order to attract any audience … The format was decided, we would become a Discotheque which also provided Live music. (Donovan 1981: 14)

In general, records infiltrated the public sphere from the least profitable to the most lucrative hours of the week. In the 1940s, it became standard for records to be played between the main band’s sets (replacing the second support band) at all but the most affluent or ‘muso’ of dance gatherings. In the early 1950s, the public use of records was facilitated by the introduction of vinyl 33 and 45 rpm records which were lighter, more portable, less breakable and had superior sound quality to 78s. This did not cause, but probably aided the proliferation of lunchtime rock’n’roll record hops. In the 1960s, most disc sessions, whether in live venues or discotheques, took place early in the week. For example, in 1963, The Scene, a well-known Mod discotheque, had exclusively recorded entertainment (‘Guy Stevens’ R&B Record Night’ and ‘Off the Record with Sandra’) only on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday nights, while they featured live bands at the weekends (New Record Mirror 2 November 1963).

In the 1970s, records began to dominate the ‘prime time’ of out-of-home entertainment on Friday and Saturday nights. Moreover, in certain circumstances, live music effectively became the interval between record sets. For example, musicians on the Northern Soul disco circuit tell of being hired to play very early or very late in the evening (when the venue was empty) to fulfil PPL licence agreements. When they did play at the height of the evening, however, patrons used the performance as an opportunity to take a break from dancing (Alan Durant in conversation, 1989). By the mid-1980s, the temporal organization of performance and recorded entertainment had been reversed: live music was relegated to the beginning of the week when profit margins were not expected to be as high, while DJs and discs were the main attraction at the weekends.

Just as dancing to discs progressed through the structure of weekly leisure time, so records were selectively assimilated by diverse premises at different rates. Records first gained a foothold in schools, community centres, youth clubs, town halls and other locations with low budgets. From non-profit premises, records moved to commercial ones – starting out small in basements, as extensions of coffee bars and as additional rooms to established venues. Only in the 1970s and 1980s, did the leisure chains start converting their ballrooms into large-scale discotheques.

By substantially cutting costs, records improved the profit margins and turnover of dance establishments internationally. Through the 1960s and 1970s, this was regular ‘news’ in relevant trade magazines: for example, when Gabriel’s Lounge in Detroit installed a discotheque, the club was able to ‘sell drinks at only a nickel above other neighbourhood tavern prices, but fifteen and twenty cents below prices charged by clubs with live entertainment’ (Billboard 20 March 1965). In fact, one juke-box manufacturer ran a hard-sell advertising campaign stating that they ‘pre-programmed profits into their records’ (Seeburg ads in Billboard 1965). In the United States, this was not much of an exaggeration. In 1965, Billboard reported that juke-box collections amounted to $500 million, half the total of television billings but substantially more than the $275 million motion picture receipts and the $237 million in radio billings (Billboard 15 May 1965). However, PPL licensing restrictions delayed investment in technology in Britain, hence, fewer juke-boxes and house sound-systems were installed and ‘mobile discotheques’ were heavily relied on until the late 1970s. But the expense of live music was not only one of musician labour, it was also one of the investment in the technologies of ‘liveness’, of instruments, amplification, MIDI and sound engineer controls, and in the crews of roadies and technicians needed to move and operate it. From this point of view, discotheques, even lavish ones, are a rational capital investment.

The big boom in investment in permanent discotheque facilities followed the top forty chart achievements of disco – a music made specifically for discotheques which signalled the extensive and durable presence of the institution. In March 1978, London’s main listing magazine, Time Out, began publishing a weekly listing of discotheques, ‘evaluating the music, the ambience, the prices and people’ (Time Out 24–30 March 1978). Much of this activity took place in the wake of the phenomenal sales of the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack album, which was the biggest selling album of all time (until 1983 when it was superseded by Michael Jackson’s Thriller). It is telling that the film premiered in Cannes, not at the film festival in May but at MIDEM, the annual international record industry convention, in January 1978. This was a music-led media package. After the non-specialist media exposure the genre received on the coat-tails of the film, discotheques were hailed as a ‘revolution’ rather than a ‘fad’ in entertainment for the first time. As Britain’s main trade paper, Music Week, wrote in 1978:

the disco revolution in America has not been equalled since rock exploded in the fifties – and it will happen here too … the rock takeover, the disco takeover … We’re in the midst of a British club boom. More discos have opened their doors in the past month, it seems, than during the rest of the year. Many are following an All-American format. (Music Week 16 December 1978)

Leisure chains (like Rank, Mecca and First Leisure) and breweries (like Whitbread) adopted rolling programmes of refitting and refurbishing (cf. Disco International 1976–84). When disco music went out of fashion, pubs and dancehalls continued to be converted and discotheques purpose-built. As the first discotheque trade magazine, which began publication in 1976, wrote: ‘It’s comforting to predict that as America’s disco dinosaur becomes extinct, the social bedrock of the British disco is as firm as ever’ (Disco International December 1979). Throughout the 1980s, the size and number of disc-dance venues continued to increase.

Developing alongside the permanent sites with their own alternative ancestries were extended versions of the mobile discotheque. With them, records became the source of music for increasingly big events, to the extent that they eventually entertained arena-size crowds of ten and fifteen thousand people at ‘raves’ in unconventional locations. ‘Raves’ grew out of the semi-legal warehouse parties organized by young entrepreneurs in reaction to the expansion of the leisure industry and perceived ‘commercialization’ of night-life in the 1980s. The warehouse events, in their turn, drew their inspiration from the Afro-Caribbean ‘sound-systems’ which had been a feature of black entertainment since the 1970s. All three incarnations of the discotheque took advantage of its flexibility and mobility, exploring new kinds of environment which contributed to novel ‘atmospheres’.

The development and spread of permanent and mobile discotheques is part of a general re-location and re-positioning of live music. Before the Second World War, the majority of Musicians’ Union members were employed to play at dances of one sort or another. Today, few British musicians make a living from dance engagements. Live dancehalls dwindled in number and deteriorated in condition; some were restored for the use of devoted ballroom dancers; many were transformed into discotheques, converted into bingo halls or less commonly into cinema multiplexes and concert halls. The economics of music is such that live music is only profitable under certain conditions – and dance venues are no longer one of them.

Despite the resilience of live ideology, the professional performance of popular music has receded. The slow transition has gone relatively unnoticed. Periodically, the threatened closure of premier venues has provoked concern about a general decline of live music. In the seventies, for example, the Rainbow Club was on the brink of closure for several years and became a symbol of the threat discos posed to live music in London (cf. Melody Maker and New Musical Express 1973–5). In the 1990s, the possible closure of the Town and Country Club spurred similar outcries: ‘Live music in London is in crisis: audiences are down, venues are changing hands at an alarming rate and many promoters are being forced to rely on club DJs instead of bands … the decline of live music is a national phenomenon … there is a whole generation out there which isn’t being encouraged to go to gigs’ (Time Out 3–10 April 1991).

That live music has been marginalized is perhaps best demonstrated by the fact that in many British towns, the principal live venues have been owned, operated or subsidized by local governments and student unions. In the 1990s, venues in York, Sheffield, Cambridge, Norwich and London opened and closed their doors at the expense of local taxpayers. The largest share of middle-sized gigs, however, are hosted by university student unions who support around eight hundred venues around Britain. When the national government threatened to pass legislation preventing student unions from funding ‘non-essential’ campus activities, the importance of this subsidy became clear; if events had to be self-supporting, roughly seventy-five per cent of their gigs would have to be cut because ticket prices would be forced up beyond the reach of most students (Music Week 19 February 1994). Needless to say, college students now make up the bulk of the audience for live popular music and the live circuit is heavily dominated by a few subgenres, like alternative rock and indie music (cf. Central Statistical Office, General Household Survey 1986; EMAP Metro, Youth Surveys 1988). Another subsidizer of this scene is the record industry who give ‘tour support’ to emerging acts because they see gigs as a means of building fan bases, establishing markets and promoting records.

One live circuit which can be lucrative (but often incurs huge losses) is the arena and stadium concerts of the established pop and rock act. This sector would not exist if it were not for the massive audiences generated by records and other media. Here, tours are again sponsored by record companies, but also by advertisers of soft and alcoholic drinks, youth-oriented clothes and the like. While promoters of this sector (and there are not many in this league) make money from ticket prices, the bulk of revenue for the band often comes from the sale of merchandise such as T-shirts, posters and tour booklets. Although merchandising had been around since the 1960s, it was not until the 1980s that it became integral to the economics of touring (and part and parcel of developing an artist) to the extent that acts now often sign merchandising agreements at the same time as they sign recording contracts. The landmark legal action through which artists gained the copyright to their image was against a company producing unofficial Adam and the Ants merchandise in the early 1980s. Some indie bands like James or the Inspiral Carpets (famous for their ‘Cool as Fuck’ T-shirts) allegedly became wealthy by ‘self merchandising’ (Applause May 1991).

All this is not to argue that live music is dead, but that it no longer appeals to the broad base of the population that it once did and is no longer economical in many of the circumstances it once was. Much live music is made by unpaid amateurs and semi-professionals. Performance is an enjoyable hobby for many pub musicians, buskers, church choirs and brass bands (cf. Finnegan 1989). However, some bands in this category, who aspire to a recording contract but need to be heard in the appropriate venue first, may find themselves paying the venue for the privilege of performing. These ‘pay for play’ situations usually take the shape of ‘ticket deals’ where the band buys fifty tickets then sells them to friends.

In 1988, the Monopolies and Mergers Commission recommended that PPL completely withdraw its musician employment requirements. The Commission agreed with dance operators who argued that the live music requirements were ‘not only expensive but pointless’ for two reasons. First, they argued that the dance sound conveyed by the records ‘cannot be reproduced by instrumentalists playing direct to an audience’. Second, they maintained that ‘audiences prefer recorded sound’ (Monopolies and Mergers 1988: 41). As a result, live music (or rather the requirement to hire musicians) was not found to be in the public interest. The ruling against the Musicians’ Union is typical of the fate of much union-related legislation under the Thatcher government. However, in few countries other than Britain, did musicians enjoy such protective arrangements in the first place. Later, Musicians’ Union representatives would admit that live music ‘has ceased to be “hip”. Clubs with name DJs and the latest remixes are what appeals to people today’ (Mark Melton, IASPM conference, 19–21 April 1990).

For over forty years, the Musicians’ Union and the dancehall/discotheque operators negotiated their conflicting interests through the mediation of the record company collective body, PPL. Given their disparate financial stakes in ‘phonographic performance’, the relatively congenial relationship between the Musicians’ Union and the record companies requires some explanation. The benefits to the MU are more apparent. Because all copyrights were those of the record company, the Union’s rights’ revenue was entirely dependent on its donation by PPL. Between 1947 and 1989, PPL gave 12.5 per cent of its net royalty revenue to the MU in respect of ‘the services of unidentified session musicians’. In 1987, that percentage amounted to £1.3 million. The reasons why PPL agreed to restrictions on the use of its product are less obvious but perhaps more numerous. First, the Union helped PPL maintain its control on repertoire in so far as it forbade its members to record with non-PPL record companies. Although PPL administered the rights of ninety per cent of all commercial sound recordings in the late 1980s, its monopoly was much less secure in the 1950s and 1960s (cf. Musicians’ Union Report 1961). Second, Union members monitored record performances and copyright infringement at a local level – something PPL, with a staff of less than sixty, had never been equipped to do. It was Union members who wrote letters to local newspapers, knocked on venue doors, censured club managers and effectively enforced copyright legislation on the ground. Third, the Musicians’ Union helped legitimate the record companies’ claims to copyright as a reward and incentive for creative production. As a 1989 PPL press release explained: ‘The British recording industry is dependent upon the services of musicians for the continued uninterrupted production of excellent sound recordings. This requires a healthy broad based musical profession covering the whole spectrum of performance.’ Finally, despite the fact that the record industry does not profit directly from live performance, but rather spends substantial sums on tour support, record company executives have tended to believe that the most artistically and commercially successful music comes from live ‘working’ acts (cf. Negus 1992: 52–4). The ability of a band to perform live is seen as insurance for a strong image and long career. Since disco, the global successes of non-live dance music have led to a proliferation of in-house and satellite dance labels and to ‘club promotions’ departments (whose aim is to nurture fan bases by plugging records to key DJs). Nevertheless, the ideal of the traditional performing rock group still prevails in many record companies who see the live version of authenticity as a key selling point.

Since the 1950s, records have supplanted musicians as the source of sounds for most social dancing and contributed to the re-location and re-definition of live music in general. This section has explored the technological, economic and legal determinants of the shifting public presences of recording and performance. Musician resistance to the enculturation of records was only effective in so far as it could be seen to coincide with the ‘public interest’. When the Union eventually lost the ideological battle, it was only a matter of time before it lost the legislative one. Changes in the ideological status of recorded entertainment were dependent on several key factors which are the subject of three of the next four sections. First, records increased their allure as a result of being affiliated with the new types of occasion, new social spaces and ‘new’ social groups – all of which contributed to the increasing subcultural authenticity of records. Second, records adapted to their public use, changed their format to suit discotheques and to satisfy the exigencies of a new profession, the club disc jockey. And, third, as the studio rather than the stage became the key site for the origination of music, so recordings in certain genres began to acquire aura.

‘Real’ Events and Altered Spaces

The authentication of discs for dancing was dependent on the development of new kinds of event and environment, which recast recorded entertainment as something uniquely its own, rather than a poor substitute for a ‘real’ musical event. These new time-frames and spatial orders exploited the strengths and compensated for the weaknesses of the recorded medium. By using new labels, rubrics, interior designs and distracting spectacles, disc dances were rendered distinctive. They were effectively transformed from an occurrence into an occasion, from a migrant practice into a unique place, from a diverting novelty into an entertainment institution.

Before record hops, dancing to discs was not a cultural event in itself. The use of records was not highlighted in flyers, listings or advertisements. The Musicians’ Union protested that dances using records were advertised in such a way as to create the impression that a live band would be playing. More peculiarly, Union members often reported that audiences didn’t notice the absence of performers. In 1953, one member contended that one young dance crowd had no idea they were dancing to records: ‘Amplification was so good as to be indistinguishable from an actual band heard outside the hall; and inside, soft lights, and a quick-change of records made the absence of a band unnoticeable. [There were] about 300 teenagers jiving like mad entirely oblivious of no band being present’ (Musicians’ Union Report 1954). Similarly, another MU member claimed that he had attended a musical play in which records had been so perfectly synchronized with voice and action that the audience thought an orchestra was playing. When he told people sitting on either side of him, they allegedly refused to believe him. He concluded his report with the lesson: ‘Members will therefore appreciate that the public, unless they are properly informed, will not know whether the music they are hearing is recorded or an actual live performance’ (Musicians’ Union Report 1956).

Although these reports are undoubtedly exaggerated in the direction of stereotypes about mass culture and false consciousness, it does appear that many people didn’t note the absence of musicians during this period. When asked today whether they danced to records at their local dance halls and youth clubs before rock’n’roll, people tend to remember if they were dancing to a band but not if they weren’t. This may be evidence of the ability of records to ‘simulate’ in Baudrillard’s sense of the word; they do not so much imitate as ‘mask the absence’ of performance (Baudrillard 1983a: 11). However, it is also testimony to the more mundane fact that, in the reports, the music was subordinate to, first, a social event and, second, a theatrical spectacle. Given these conditions of consumption, the audience didn’t give the music the attention musicians expect and appreciate. In Benjamin’s terms, these audiences were ‘distracted’: they absorbed the music but the music did not absorb them (Benjamin 1970: 239).

Rock’n’roll record hops, however, focused favourable attention on the entertainment format. In the US, the record ‘hop’ was endorsed by the new and still glamorous medium of television with the after-school show, American Bandstand. In Britain, the American import with a distinct name brought dancing to discs into vogue for the first time. ‘Hops’ gave the activity a distinct identity, transforming it into a noteworthy event rather than simply an intermission or occurrence. Significantly, record hops were identified with youth and youth alone. Like the spate of Hollywood ‘teenpics’, they capitalized on the emergence of youth as a consumer category and cultural identity. Conveniently, youth were the group with the least prejudice about the inferiority of recorded entertainment and the one with the most interest in finding a cultural space they could call their own. More than any other cultural phenomenon of the fifties, record hops came to symbolize the new youth culture. Along with labels like ‘teenager’, they contributed to a heightened consciousness of generation and, with their large-scale collective gathering, fuelled the first fantasies of a movement of youth. Records had become integral to a public culture; they were the symbolic axis around which whirled the new community of youth.

Later incarnations of disc dances did not target only youth, but smaller demographic segments and shades of taste. In 1966 in New Society, Reyner Banham argued that the cultural formations that grew up around records were characterized by what he playfully called ‘vinyl deviationa’. One of the main social functions of records – their distribution of culture – had been superseded by radio. As a result, the gramophone became ‘a system for distributing deviant sound to the disaffected cultural minorities whose peculiar tastes are not satisfied by the continuous wallpaper provided by radio [like the] BBC’ (New Society 1 December 1966). Of course, dance clubs are not only significant for minority taste cultures, but also for class, ethnic and sexual ones (cf. chapter 3).

The enculturation of records for dancing was first fostered by the development of new kinds of event and, only second, promoted by new kinds of environment. The initial 1950s disc hops did little to transform the dancehalls and youth clubs in which they took place. The following description of a record session at the Lyceum Ballroom in the Strand, for example, contrasts the traditional architecture with the new cultural form:

The Lyceum was originally a theatre, and Mecca Dance Halls Ltd have left most of its Edwardian-baroque opulence untouched. Above, all is crimson and gold, cherubs and swags of fruit. On the band stand, a sharp young man in horn rimmed spectacles fades the records in and out on the two turntables of the enormous record player. On the floor over a thousand teenagers jive … the atmosphere is solemn and dedicated … All the dancers without exception wear the fashionable cut-off expression. (Melly 1970/1989: 68–9)

In the early 1960s, the ‘discotheque’ rendered dancing to discs fashionable in the way the record hop had done a few years before. This time, however, the institution was conceived as a French import and extended its influence to its architectural surroundings. Changes in environment were crucial to the definition of the new institution; they were meant to complement the culture of contemporary youth. La Discothèque in Wardour Street, for instance, was very dimly lit, gloomy by some accounts, with a number of double beds in and around the dancefloor. Invoking the new permissive sexual mores, the outlandish interior was an attraction in itself. The Place in Hanley near Stoke-on-Trent provides another example. It was lit by red light and decorated entirely in black with the exception of a few rooms: the entrance hall was sprayed gold, the toilets sported imitation leopard-skin wallpaper and a small sitting-room was painted white, lit by blue light and called ‘the fridge’ (cf. Donovan 1981).

The spaces of 1960s’ discotheques defined themselves against the architecture of the dancehalls whose interiors stayed the same for years and whose models of elegance were royal (hence the ‘Palais’ and ‘Empires’) or relics of nineteenth-century bids for respectability (which referenced the classical world of ‘Lyceums’ and ‘Hippodromes’). Either way, the ideologies of ballrooms did not speak to the youth of the day. Discotheques were emphatically different and self-consciously unconventional. They were lounges, rooms or simply spots; they were places with presence rather than palaces, hence names like the Saddle Room, the Ad-Lib, the Place and the Scene. The suffix ‘a-Gogo’ was also used internationally to make their existence as young urbane dancing establishments absolutely clear: London and Los Angeles had Whisky-a-Gogos, named after the Parisian club. Chicago not only had a Whisky-a-Gogo, but a Bistro-a-Gogo, Gigi-a-Gogo and a Buccaneer-a-Gogo (Billboard 6 March 1965).

But transformations in name and interior design did not stop here. The institution continually renovated and effectively rejuvenated itself in order to appeal to an ever-shifting market of youth. Late-sixties’ discotheques would embrace psychedelic and strobe lighting, slide projectors and hanging beads. Seventies ‘discos’ would become a maze of shiny futuristic surfaces, chrome party palaces of mirrors and glitter balls. Eighties ‘clubs’ abandoned mirrors: walls in black or grey were particular favourites early in the decade, while painterly postmodern or tribal styles made their appearance in the second half of the decade. Late eighties ‘raves’ took dance events outside what had become ‘traditional’ venues to unorthodox locations in industrial districts and remote rural areas. Each new version of the institution was meant to be an advance on the old – an adventurous departure into a realm which seemed to have fewer rules and regulations.

The fresh names and renovated interiors were not simply a means of rejuvenation: the discotheque’s constant search for liberation from tradition extends to the legacy of British class cultures. The early-sixties discotheque not only rejected the aristocratic fantasies of the ballroom but also effaced the hierarchical distinction between the elite nightclub and the common dancehall. The discotheque, like youth culture generally, was positioned as classless. In 1965, George Melly described discotheques as ‘those wombs of swinging London’ which were ‘virtually classless’ where ‘success in a given field is the criterion and, in the case of girls, physical beauty’ (Melly 1970/1989: 104). A few years later, Tom Wolfe took a more critical view, suggesting that these youngsters seemed to be classless because they had dropped out of the conventional job system: ‘It is the style of life that makes them unique, not money, power, position, talent, intelligence … The clothes have come to symbolize their independence from the idea of a life based on a succession of jobs’ (Wolfe 1968b: 104).

Each change in institutional identity positioned the new disc dance as significantly different from what went before. Generally, the ‘revolution’ in leisure was seen as both democratic and avant-garde. ‘Discotheques’, ‘discos’ and ‘clubs’ were all meant to be both exclusive and egalitarian, classless but superior to the mass-market institution that preceded them. Raves, in their turn, were enveloped in discourses of utopian egalitarianism: they were events without door policies where everybody was welcome and people from all walks of life became one under the hypnotic beat. But the discourse could hardly be tested, for only those ‘in the know’ could hear of and locate the party. Moreover black and gay youth tended to see rave culture as a straight, white affair.

It is a classic paradox that an institution so adept at segregation, at the nightly accommodation of different crowds, should be repeatedly steeped in an ideology of social mixing. The discotheque/disco/club/rave regularly re-invented itself to maintain an eternal youth and to obfuscate dated relations to class cultures. As Barbara Bradby argues, this kind of utopianism ignores the subordinate position that women occupy at most levels of rave culture (cf. Bradby 1993). The dance acts, music producers, DJs, club organizers and bouncers who structure the events are predominately male and require that women prove themselves twice over if they want to do more than sing, check coats or tend the bar. Moreover, although raves are supposed to be ‘sexless’ affairs – that is, clothing is unisex and participants are not there to get laid – it does not follow that they are necessarily sexually progressive.

The regular redecoration of the discotheque also addressed the main deficiency of recorded entertainment. Eye-catching interiors were meant to compensate for the loss of the spectacle of performing musicians. In the 1960s, the biggest global juke-box manufacturer, Seeburg, publicly lamented the machine’s ‘negative image’ (Billboard 27 February 1965). The key to improving its status, they argued, was their new high volume, minimum distortion, stereo juke-box called ‘DISCOTHEQUE’, which they hoped would be accepted ‘as a form of entertainment in much the same way as [the public] accepts films, radio or television’ (Billboard 15 May 1965). Crucially, the machine was accompanied by an ‘INSTANT NIGHT CLUB’ package of wall panels, modular dancefloor, napkins, coasters and other decorations ‘needed to transform a location into a discotheque’ (Ad in Billboard 23 January 1965). Equally significantly, the wall panels portrayed life-size white jazz musicians in the midst of a spirited jam session. Intended for the wall behind the juke-box, these panels offered a literal solution to the phonograph’s problem of having no visual focus or, as Dave Laing writes, ‘a voice without a face’ (cf. Laing 1990).

Although this sort of literalism was relatively rare, one trajectory in the changing shape of discotheques has been the proliferation of visuals. Lighting, in particular, has become an elaborate accompaniment to the music, emphasizing its rhythms, illustrating its chords. Sometimes, the roving coloured beams and flashing strobes decorate the dancers, making a better spectacle of the crowd. At other times, swishing lasers and figurative patterns of light are an optical phenomenon in their own right. Computer-generated fractals and other abstract designs of coloured light can act as visual equivalents of the instrumental sounds of house and techno music, while film loops, slide projectors and music videos punctuate the space with figurative entertainment. The discotheque bears witness to the symbolic possibilities of electric light which, since the nineteenth century, has been used to signal the consequence and difference of night-time social gatherings (cf. Marvin 1988).

In contrast to the record sessions held in old-style dancehalls, discotheques attempted to offer complete sensory experiences – ones often intensified by the use of alcohol and/or drugs, which have been mainstays of youthful dance experience since disc sessions took on their own premises. Only with the discotheque of the 1960s did the institution develop into a total environment where ‘dream and reality are interchangeable and indistinguishable’ (Melly 1970: 9). In what must be the first study of discotheques, Lucille Hollander Blum argues that their appeal results from the way they offer ritual catharsis. Discotheque dancers, she asserts, experience a ‘delirious sense of freedom’, enter a ‘state of complete thoughtlessness’ and escape from ‘present day reality’ (cf. Blum 1966). Since then, discotheques have evolved further into multimedia installations whose worlds are contiguous with the recorded fantasies of music video and the virtual realities of computer games, but are still a site of tangible human interaction. ‘Club worlds’ are markedly divorced from the work world outside. Door restrictions sharply divide inside from outside, while long corridors, inner doors and stairways create transitional labyrinths. Raves add the pilgrimage, the quest for the location, to extend the ritualistic passage. Like Alice’s rabbit hole, both convey the participant from the mundane world to Wonderland.

Disc Jockeys and Social Sounds

Discotheques have carved out distinctive times and places for recorded music. With their different senses of place and occasion, they have, as their name suggests, effectively accommodated discs. But records have also adapted to the social and cultural requirements of the evolving dance establishment, modifying their formats and formalizing the manner in which they are played. Disc jockeys have had a decisive role in conducting the energies and rearranging the authenticities of the dancefloor.

Essential to the altered space of discotheques is the enhanced acoustic atmosphere which results from high volume, continuous music. The initial popularity of juke-box-fitted coffee bars and purpose-built discotheques over the record sessions in dancehalls related not only to architectural style but also to improved sound-systems. According to one music weekly of the early sixties, La Discothèque in Streatham was ‘more than a dance hall’ because of the ‘quality and the volume’ of the records they played (New Record Mirror 19 January 1963). In the 1950s, record playback technology was not able to fill a large ballroom with high fidelity sound. Even in the early 1960s, few discotheques could provide all-around sound, highs or lows, or thumping bass.

In the mid-1960s, many juke-box manufacturers, including the three largest, Seeburg, Wurlitzer and Rowe, started to manufacture extended-play records for their dance-oriented juke-boxes – a decade before record companies extended the length of the single with the twelve-inch format. Seeburg argued that the discotheque would prevail as a form of entertainment only if it offered ‘uninterrupted music’. As a result, they issued dance music in the format of the ‘Little LP’, a recording with three titles per side, with music in the lead-in and lead-out grooves, amounting to seven and a half minutes of continuous music (Billboard 6 February 1965 and 1 May 1965). So, the practice of dancing to discs began to affect the design of the record itself.

Record companies were slow to react. At around this time, Billboard introduced a discotheque chart because they said that the discotheque was having ‘a major effect on the entire music and entertainment industry. A look at Billboard’s Hot 100 shows discotheque industry material all over the chart’ (Billboard 27 February 1965). But it was not until a decade later, with disco music, that the industry really opened its eyes to the ‘concept of transforming a routine nightclub into a catalyst for breaking records’ (Wardlow in Joe 1980: 8–9). In his extensive analysis of the introduction of the twelve-inch single in America, Will Straw argues that record company interest in dance clubs coincided with shrinking radio play-lists; promotions departments were looking for alternative means of plugging their music (cf. Straw 1990).

In the 1970s, extended twelve-inch singles became a standard product amongst American, then British, record companies. The idea came from American DJs who had been mixing seven-inch copies of the same record for prolonged play. Some began recording their mixes, editing them on reel-to-reel tapes, then playing them in clubs. When these recordings were transferred to vinyl, the extended remix was born. Record labels became involved when they realized that discotheques were sufficiently widespread to make catering to them with special vinyl product a promotional necessity.*

The new record format was better suited for playing at high volume over club sound-systems and its extended versions had instrumental breaks where the song was stripped down to the drums and bass with very little vocal in order to facilitate seamless mixing of one track into another. (Interestingly, dance bands of the 1920s and 1930s constructed dance numbers in a way not unlike twelve-inches, with extended instrumental introductions and finales and short segments of lyrics in which the vocal acted as if it were merely another instrument. Simon Frith in conversation.) These extended dance ‘tracks’ (rather than ‘songs’) helped sustain the momentum of the dancefloor and contributed to the other-worldly atmosphere of the discotheque. The constant pulse of the bass blocks thoughts, affects emotions and enters the body. Like a drug, rhythms can lull one into another state. With rave culture, this potentiality was ritualized as the ‘trance dance’ by dancers actively seeking an altered state of consciousness through movement to the music.

Pre-eminently, twelve-inch records were made specifically for DJs. The recorded entertainment at the heart of disc cultures is not automated. DJs incorporate degrees of human touch, intervention and improvisation. They play a key role in the enculturation of records for dancing, sometimes as an artist but always as a representative and respondent to the crowd. By orchestrating the event and anchoring the music in a particular place, the DJ became a guarantor of subcultural authenticity. As Daniel Hadley writes, although DJs lack absolute control over the proceedings, they are ‘still responsible for the creation of a musical space, a space which is formed according to the expectations of the crowd and the specific kinds of DJ practices in place’ (Hadley 1993: 64).