3

Exploring the Meaning of the Mainstream (or why Sharon and Tracy Dance around their Handbags)

A Night of Research

Saturday, 22 September 1990. Wonderworld, London W8, 11 p.m. It’s exactly eleven and I’m waiting for Kate.* We’ve never met before, but she knows I’m researching clubs and has promised to show me ‘how to have fun’. The ‘hardcore techno-house’ of the dancefloor is just audible from here. Two women police officers patrol on foot. Mostly same-sex groups wear casual clothes and casual expressions; they walk slowly and deliberately until they’ve got past the door staff, then plunge down the stairs into the club. I feign uninterest because clubbing is the kind of activity that shuns official, parental, constabulary or even ‘square’ observation. Clubbers often voice antipathy towards the presence of people who don’t belong and come to gawk.

A few minutes later, Kate jumps out of a black cab. She’s energetic and her immaculately made up eyes gleam. Her brother runs this club, so she asks the doorwoman to ‘sort us out’. The woman takes a pack of cards and hands me a three of diamonds, smiling: ‘This will get you all the way.’ We descend a flight of steps where a bouncer inspects my card, then ushers us in. The doorwoman insisted that this club, run by ex-rave organizers in rave style, has no door policy – absolutely anyone could come in. Nevertheless, the crowd looks pretty homogeneous. They are mostly dressed in a late version of the acid house uniform of T-shirts, baggy jeans and kickers boots; they’re white and working-class. There is also a handful of Afro-Caribbean men hanging-out near the door who look as if they might be friends of the entirely black crew of bouncers.

We walk around the club. The venue is early-eighties plush, but it’s transformed for tonight’s club by large unstretched glow-in-the-dark canvases of surreal landscapes with rising suns and psychedelic snakes. A white boy, wired and talking a mile a minute, stops me in my tracks: ‘Want some “E”?’ He’s referring to ‘Ecstasy’ and he’s eating his words. The volume of the music is such that I can only catch bits of his sales pitch: ‘I got burgers and double burgers … fifteen quid.’ He is a poor advertisement for the effects of his wares. From his aggressive and jumpy delivery, I assume that he is really on some speed concoction or perhaps this is his first night on the job.

We descend more stairs to the VIP room where another bouncer gestures for my card, then waves us in. No door policy upstairs, but an exacting one down here. This room is so restricted that, at this hour, there is no one here except the barmaid. But it’s still early. We get a Coke and a mineral water and sit down. It feels private. Kate is very much at home. ‘Tell me about your research then.’ She’s genuinely interested in my work, but also probing into whether I can be trusted. Her brother is one of the original rave organizers, who began by putting on parties in barns and aircraft hangars, then went legit, organizing weekly clubs for ravers in venues around London. As Kate tells it, the police monitored all their parties from the beginning, but as soon as the ‘gutter press’ were hard up for a front-page story the scene got out of hand: ‘Kids, who shouldn’t even have known about drugs, read about the raves in the Sun and thought, “Cor – Acid. That sounds good. Let’s get some”, and loads of horrible people started trying to sell “swag” drugs.’

During our conversation, the VIP room has filled up. Kate suggests I meet her brother who is sitting at the bar with a long blonde and a bottle of Moët et Chandon on ice. He is in his early twenties and wears a thick navy-and-white jumper, something which immediately distinguishes him from those here to dance. Kate tells him that I’ve never taken Ecstasy (‘Can you believe it?’) and that we are going to do some tonight. He’s not pleased. ‘How do you know she won’t sell this to the Daily Mirror?’ he asks. Kate assures him that she’s checked me out, that I’m all right. Later, they explain that they want someone to tell the ‘true story’ of acid house and that they’ll help me do it as long as I don’t use their names.

Kate pours me a champagne and takes me aside. A friend has given her an MDMA (the pharmaceutical name for Ecstasy) saved from the days of Shoom (the mythic club ‘where it all began’ in early 1988). We go to the toilets, cram into a cubicle where Kate opens the capsule and divides the contents. I put my share in my glass and drink. I’m not a personal fan of drugs – I worry about my brain cells. But they’re a fact of this youth culture, so I submit myself to the experiment in the name of thorough research (thereby confirming every stereotype of the subcultural sociologist). Notably, there’s ‘Pure MDMA’ for the VIPs and ‘double burgers’ for the punters. The distinctions of Ecstasy use are not unlike the class connotations of McDonald’s and ‘no additives’ health food.

Millennium, London W1, 1 a.m. Millennium is the kind of club that pretends it’s not mentioned in listings magazines but is. It imagines itself as entirely VIP chiefly because it’s heavily into cocaine. At first, they won’t let us in, but Kate uses her brother’s name, and we’re admitted free. The crowd is older than average (mid-to-late twenties), dressed in designer-labels (lots of Jean-Paul Gaultier and Paul Smith), and obviously concerned about who’s who. There is a contingent of gay men by the bar and a scattering of women with handbags and high heels on the dancefloor. The music is familiar, dance-oriented pop.

The club’s organizer is famous for his early-eighties New Romantic clubs. He looks worn out. His face is pale and dry. Later, when I tell people I went to his club, they ask ‘Is he still going?’ The question seems to be written on his face. He’s a has-been in a world whose fashions last six months and old in a world that fetishizes youth. As we shake hands, he introduces me to a journalist who covers the club scene.

Mick writes regularly for a weekly music magazine and a daily newspaper. After a chat about sociology and some people we know in common, he pulls out a flyer for a rave in a church, suggesting I come along. The flyer is in the form of an elaborate card: its front cover displays a crest of a chicken dressed as a vicar holding a bible; inside are an odd mixture of quotations from the New Testament, DJs and clothing designers. It’s a charity benefit – ‘strictly invitation only’.

Cloud Nine, London EC1, 2:30 a.m. Cabs are scarce, but we’re finally in one, driving around looking at churches as the invite gives only a vague address. The driver stops and asks two police on their beat for directions. The policewoman peers into the back seat and asks, ‘Are you going to see Boy George?’ She’s heard about this event and there is trace of envy in her voice. But her partner dutifully points the way – ‘take your first left, then second right.’ This club scene sees itself as an outlaw culture, but its main antagonist is not the police (who arrest and imprison) but the media who continually threaten to release its cultural knowledge to other social groups.

St George’s is an eighteenth-century, neoclassical church on a side street. Nothing announces the club except for a few lights and a lone black doorman who, although he’s a giant, looks dwarfed between the temple’s columns. The DJ console is on the altar. The congregation dances, leans and lounges on pews. The all-male line-up of DJs are known to be trend-setters; they play records before their commercial release and influence the sound of the national club scene. Some have their own radio shows or act as record company A&R men. Others are full-fledged ‘artists’ who have produced ‘underground’ dance hits and even number-one singles.

The dancers are aged eighteen to twenty-two, mostly white and ‘beautiful’. Typically, the girls have dressed with more attention and elaboration than the guys. A handful sport this week’s fifteen-minute fashion, sixties-style bouffants. Thick black eyeliner and pale lipstick stare at you with studied blankness from every direction. I believe this is the straight hairdressers and fashion retail crowd, with a few models and art school students mixed in for good measure. But it is often difficult to tell. Questions about work are taboo in this leisure environment. You could have a long conversation in the toilets with a woman who tells you she’s taken two ‘E’s, just been jilted by her boyfriend and is sleeping with his best friend for revenge, but ask her what she does for a living and she may well stop in mid-sentence at this insulting breach of etiquetté. It is rude to puncture the bubble of an institution where fantasies of identity are a key pleasure.

Determining social background can be just as tricky. Obviously, one cannot inquire about parental occupation. Accents can offer some indication, but it is relatively common for upper-middle-class Londoners to adopt working-class accents during their youth and vice versa. However, in their pursuit of classlessness, they are still interested in being a step ahead and a cloud above the rest. Like disco before it, acid-house-cum-rave supposedly democratized youth culture. Now, the ‘everybody welcome’ discourse lingers at some clubs and is emphatically out at others. But whether they are ‘no door policy’ or ‘invitation only’ events, the composition of their crowds generally has some coherence. The seemingly chaotic paths along which people move through the city are really remarkably routine.

Sometime after 4 a.m. – time seems to be standing still – we venture into the VIP room in the minister’s office behind the altar. It is white-walled and spartan, with a desk, fireplace and bookshelves. The room is full of men who know each other – mostly DJs and club organizers – who are talking about the quality of recent releases and club events. Around another corner, I’m introduced to the operator of a Soho venue with a long-standing reputation for the hippest DJs, music and crowd. He tells me he’s been running clubs since 1979, then snorts some coke off the corner of a friend’s Visa card. His blue eyes actually dart about like whirling disco spotlights and his conversation is a chaotic compilation of non sequiturs. Ecstasy turns banal thoughts into epiphanies. I see how club organizers, DJs and journalists – the professional clubbers – get lost within the excesses and irresponsibilities of youth. With no dividing line between work and leisure, those in the business of creating night-time fantasy worlds often become their own worst victims.

The lights come on. All of a sudden, it’s 6 a.m. The party’s over. The remaining dancers mill about, saucer-eyed, confused about what to do with themselves. We bump into the ‘official photographer’ of the event who tells us that Boy George never turned up and the church has to be cleaned for mass at ten o’clock. The press weren’t allowed in, but the church wanted some documentation on the fund-raiser, so they hired him. ‘Hilarious,’ says Mick, ‘what religion will suffer to stay in business.’ The photographer tells us he has a few shots the Sun would pay dearly for, but he won’t yield to temptation – it would be ‘bad faith’.

Academic Accounts of the Cultural Organization of Youth

Sociology has to include a sociology of the social world, that is a sociology of the construction of world views, which themselves contribute to the construction of the world.

Bourdieu 1990: 130

One of the prices paid by subculturalists and sociologists of youth for neglecting issues of cultural value and hierarchy is that they have become inadvertently ensnared in the problem. When investigating social structures, it is impossible to avoid entanglement in a web of ideologies and value judgements. Nevertheless, it is important to maintain analytical distinctions between: empirical social groups, representations of these people and estimations of their cultural worth. Academic writers on youth culture and subculture have tended to underestimate these problems. They have relied on binary oppositions typically generated by us-versus-them social maps and combined a loaded colloquialism like the ‘mainstream’ with academic arguments, ultimately depicting ‘mainstream’ youth culture as an outpost of either ‘mass’ or ‘dominant’ culture. In this chapter, I explore the organization of club culture by comparing the social worlds portrayed in clubber discourses with the social worlds I observed as an ethnographer. This reflexive methodological approach enables a double interrogation the meaning of the ‘mainstream’ and the social logic of youth’s subcultural capitals. In this way, I attempt to offer a fuller representation of the complex stratifications and mobilities of contemporary youth culture.

Before this, however, it is worth considering the ways in which the cultural world of youth has been previously constructed by British academics. Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979), one of the most influential texts in the field, is heavily dependent on the mainstream as the yardstick against which youth’s ‘resistance through rituals’ and subversion through style is measured. But Hebdige’s mainstream is abstract and ahistorical. For example, he compares punk apparel, not to disco attire or other contemporary clothing, but to ‘the conventional outfits of the man and woman in the street’ (Hebdige 1979: 101). He contrasts punk ‘anti-dancing’ with the ‘conventional courtship patterns of the dancefloor’ (Hebdige 1979: 108). One could point out, however, that the influence of ‘conventional courtship patterns’ has been decreasing since the Twist. Although end-of-night ‘slow dances’ linger at school discos and are occasionally subject to ironic revival, they have been marginal to club culture for almost thirty years.

Each reference to the ‘mainstream’ in Subculture points in a different direction, but if one added them up, the resultant group would be some version of the ‘bourgeoisie’ whose function within Hebdige’s history is, of course, to be shocked. While this framework complements his repeated characterization of subcultural youth as ‘predominantly working-class’, it hardly does justice to the bulk of young people who are left out of the picture. Hebdige’s multiple opposition of avant-garde-versus-bourgeois, subordinate-versus-dominant, subculture-versus-mainstream is an orderly ideal which crumbles when applied to historically specific groups of youth.

Inconsistent fantasies of the mainstream are rampant in subcultural studies. They are probably the single most important reason why subsequent cultural studies find pockets of symbolic resistance wherever they look (cf. Morris 1988). Rather than making a clear comparison, weighing the social and economic factors, and confronting the ethical and political problems involved in celebrating the culture of one social group over another, they invoke the chimera of a negative mainstream.

When academics turn their full attention to the mainstream (and don’t just infer it from their discussion of subcultures), the results may also turn out to be reductive. Geoff Mungham’s article ‘Youth in pursuit of itself is based on research done at a Mecca dancehall in an unnamed town. Despite the singular site of his research, Mungham contends that his study is not about any particular dancehall, but about the ‘scenario of the mass dance’ which is the ‘forum for what might be called mainstream working-class youth’ (Mungham 1976: 82). In order to make this dancehall stand in for the mainstream, Mungham doesn’t rationalize its representativeness but, rather, strips it of its differences and specificities by refusing to mention details of occupation and location and by avoiding cultural references altogether. In fact, according to Mungham, the cultural aspects of the ‘mass dance’ are insignificant to its real meanings:

While the music may change, while shifting fashions and tastes may chase after new stars and performers, social relationships inside the dance hall stay unchanged. There is an order and youth partakes of it gladly. Respectable working-class youth, on its nights out, is largely quiescent and conforming. (Mungham 1976: 92)

Mungham searches for the normal, the average, the routine and the mundane. He positions his study as a counterbalance to sociology’s orientation toward the conspicuous and bizarre, repeatedly straining to emphasize the conformity, conservatism and ‘sheer ordinariness of this corner of youth culture’ (Mungham 1976: 101). In the end, Mungham describes the dance as a ‘mechanical configuration’ and as a ‘Mecamization of the sexual impulse’ (Mungham 1976: 92). Despite his ethnographic observation, he projects a ‘Mass Society’ style vision on to the Mecca dancers, portraying them in a way not unlike Adorno depicted jitterbug dancers of the 1940s as ‘rhythmically obedient … battalions of mechanical collectivity’ (Adorno 1941/1990: 40).

Both Hebdige and Mungham define subcultures and mainstreams against each other. Their antithesis partly derives from the high cultural ideologies in which both formulations are entangled. Hebdige perceives his mainstream as bourgeois and his subcultural youth as an artistic vanguard. Mungham sees his mainstream as a stagnant ‘mass’, only their deviant others are, by implication, creative and changing. Although assigned different class characteristics, both ‘mainstreams’ are devalued as normal, conventional majorities.

In her article ‘Dance and social fantasy’, Angela McRobbie questions the basis of these value judgements but still preserves their binary structure (cf. McRobbie 1984). McRobbie maintains the opposition between mainstream ‘respectable city discos’ and ‘subcultural alternatives’, but instead of exclusively celebrating the latter, she suggests that dancing offers possibilities of creative expression, control and resistance for girls and women in either place. In several essays, McRobbie has explored the substantial complications that gender poses to these distinctions, but she stops short of disputing the dualistic paradigm (cf. McRobbie 1991).

The mainstream-subculture divide is not the only dichotomy to which the musical worlds of youth have been subject. Other sociologists contrast the culture of middle-class students with that of working-class early school-leavers. For example, Simon Frith outlines a split between a mostly middle-class ‘sixth-form culture’ of individualists who buy albums, listen to progressive rock and go to concerts and a working-class ‘lower-fifth-form culture’ of cult followers who buy singles, listen to ‘commercial’ music and go to discos (cf. Frith 1981a). He links these research findings to a broader distinction between rock culture and pop culture:

the division of musical tastes seemed to reflect class differences: on the one hand, there was the culture of middle-class rock – pretentious and genteel, obsessed with bourgeois notions of art; on the other hand, there was the culture of working-class pop – banal, simple-minded, based on the formulas of a tightly knit body of business men. (Frith 1981a: 213–14)

Frith admits that this conception of two worlds is a simplification in so far as ‘pop culture’ is both younger and predominantly female in addition to being working-class. But a further problem arises. The sixth-formers of his study do espouse this us – them binarism; they ‘differentiated themselves from the masses as a self-conscious elite by displaying exclusive musical tastes’ (Frith 1981a: 208). His lower-fifth-formers, however, seem to embrace a more plural vision of music audiences – one in which the sixth-form ‘hippies’ become just one among many youth cultures. As one fifth-former says, ‘I don’t know what youth culture means. I think it means what you are – Skin, Greaser, or Hairy. I am none of these’ (Frith 1981a: 207). Frith seems to view the terrain of music crowds through the eyes of his middle-class student interviewees – the result of a ‘natural’ and, perhaps, not quite conscious identification.

In his paper ‘Nightclubbing: An exploration after dark’, Stephen Evans similarly universalizes the outlook of the students who now frequent dance clubs and distinguish themselves from a mainstream of working-class Mecca disco attenders (cf. Evans 1989). Accordingly, Evans finds two distinct nightclub cultures in Sheffield: one ‘commercial’, the other ‘alternative’. The commercial culture takes place in ‘glitzy palaces’ which play top forty chart music and are populated by white, early school-leavers of working-class origin. The ‘alternative’ culture, by contrast, is situated in darkly lit ‘dives’ which focus on the newest developments in dance music and are attended primarily by students.

There are certainly differences between the leisure cultures of early school-leavers and higher education students, but this is only one measure of difference – and not the one privileged by the working-class ‘glitzy palace’ crowd. Even in a small city like Sheffield, this schema necessarily omits specialist music club nights as well as the city’s gay and rocker clubs. It could certainly not cope with the highly differentiated activities of a metropolitan centre like London or the complex cultural axes of the national club scene.

Dichotomies like mainstream/subculture and commercial/alternative do not relate to the way dance crowds are objectively organized as much as to the means by which many youth cultures imagine their social world, measure their cultural worth and claim their subcultural capital. Hebdige, Mungham, McRobbie, Frith and Evans uncritically relayed these beliefs and, with the exception of Frith, got caught up in denigrating or, in the case of McRobbie, celebrating the ‘mainstream’.

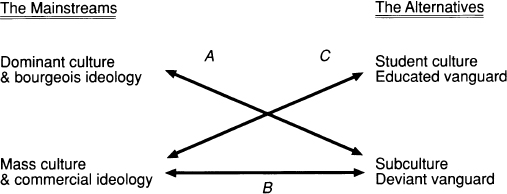

Interestingly, the main strands of thought on the social structure of youth amongst these British scholars contradict one another. One positions the mainstream as a middle-class, ‘dominant’ culture, while the other describes it as a working-class, ‘mass’ culture. Some, then, see the alternative as (middle-class) student culture, others as (working-class) subculture. (In figure 3, Hebdige and the Birmingham tradition espouse axis A; Mungham and McRobbie embrace B; Frith and Evans advocate C.) Moreover, each tradition has tended to subsume, rather than properly deal with, the contradictions raised by the other. For example, the subculturalists address the complications posed by student culture by arguing that it is not really a ‘subculture’ but a diffuse ‘milieu’ within the dominant culture (cf. Clarke et al. 1976). While sociologists, like Frith, have pointed to the student origins of many ‘working-class’ subcultures (cf. Frith and Horne 1987). These discrepancies might equally have been used to prise open the dichotomies themselves.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, when the study of popular culture was just beginning, these formulations represented important forays into mapping the social organization of music culture. In the 1990s, however, one needs to draw a more complicated picture which takes account of both subjective and objective social structures as well as the implications of cultural plurality. North American exponents of cultural studies have begun to take up the latter task. In his ‘The politics of music: American images and British articulations’, Lawrence Grossberg begins by asserting that subcultures and the mainstream have ‘fluid boundaries’ which are a ‘matter of degrees and situated judgements’ (Grossberg 1987: 147–8). Later, he goes further, contending that subculture and mainstream are indistinguishable: ‘the mass audience of pop, the mainstream of style, is the postmodern subculture’ (Grossberg 1987: 151). Grossberg does so by imploding polar opposites. For him, the centre is ‘a floating configuration of marginality’, and homogeneity is ‘a social pastiche’; conformity is the pursuit of individualism and authenticity is really co-optation (Grossberg 1987: 147–8).

In 1990s Britain, many have opted for a similar vision of plural subcultures. For example, a detailed commercial report on youth culture researched by the British Market Research Bureau and compiled by Mintel claimed that a mass of teenage consumers no longer exists: ‘Marketers and advertisers should be constantly aware that the young are not a broadly homogeneous group taking part in a mass event called the late 1980s (as was to some extent the case in the 1960s or early 1970s). In the UK, youth culture, if it exists at all, is made up of a highly diverse mixture of subcultures’ (Mintel 1988c).

Although Grossberg’s argument is in many ways appealing, two problems arise for those concerned with understanding the distinctions of youth (in both Britain and North America). First, Grossberg shuns notions of social structure in favour of plurality without pattern or design. He ultimately pictures youth as an undifferentiated mass – homogeneous in their heterogeneity and indifferent to distinction. Second, Grossberg ignores the social significance of the concept of the ‘mainstream’ to youthful maps of the cultural world – which are arguably stronger in Britain, but still influential and active in the States (cf. Christenson and Peterson 1988).

Rather than painting an omniscient picture of the social organization – or disorganization – of youth culture, I investigate the mainstream as an important feature of the ‘embodied social structure’ of youth. Popular discourses about dance crowds have the crucial function of anchoring and orienting their beholders in the social world, but they do not offer a value-free account of that world. So, while it is important to take up youth’s perspectives and grant credibility to their views (cf. Becker 1967), it is also vital to contextualize, compare and contrast their outlooks. In the following sections, I shall explore some of the ideological functions and social ramifications of the mainstream. I’ll then consider some of the methodological and epistemological problems involved in researching and representing the social organization of club culture.

The Social Logic of Subcultural Capital

‘Clubland’, as many call it, is difficult terrain to map. Club nights continually modify their style, change their name and move their location. Individual clubbers and ravers are part of one crowd, then another, then grow out of going out dancing altogether. The musics with which club crowds affiliate themselves are characterized by a fast turnover of singles, artists and genres. Club culture is faddish and fragmented. Even if the music and the clothes are globally marketed, the crowds are local, segregated and subject to distinctions dependent on the smallest of cultural minutiae.

For these reasons, many clubbers would say it is impossible to chart the patterns of national club cultures. Nevertheless, they constantly catalogue and classify youth cultures according to taste in music, forms of dance, kinds of ritual and styles of clothing. They carry around images of the social worlds that make up club culture. These mental maps, rich in cultural detail and value judgement, offer them a distinct ‘sense of [their] place but also a sense of the other’s place’ (Bourdieu 1990: 131). So, although most clubbers and ravers characterize their own crowd as mixed or difficult to classify, they are generally happy to identify a homogeneous crowd to which they don’t belong. And while there are many other scenes, most clubbers and ravers see themselves as outside and in opposition to the ‘mainstream’.

When I began research in 1988, hardcore clubbers of all kinds located the mainstream in the ‘chartpop disco’, specifically the Mecca disco. ‘Chartpop’ did not refer to the many different genres that make it on to the top forty singles sales chart as much as to a particular kind of dance music which included bands like Erasure and the Pet Shop Boys but was identified most strongly with the music of Stock, Aitken and Waterman (the producers of Kylie Minogue, Jason Donovan, Bananarama, Kim Appleby and other dance-oriented acts). Although one is most likely to hear this playlist at a provincial gay club, the oft-repeated, almost universally accepted stereotype of the chartpop disco was that it was a place where ‘Sharon and Tracy dance around their handbags’. This crowd was considered unhip and unsophisticated. They were denigrated for having indiscriminate music tastes, lacking individuality and being amateurs in the art of clubbing. Who else would turn up with that uncool feminine appendage, that burdensome adult baggage – the handbag? ‘Sharon and Tracy’ were put down for being part of a homogeneous herd overwhelmingly interested in the sexual and social rather than musical aspects of clubs. Many clubbers spoke of ‘drunken cattle markets’, while one envisioned a scene where ‘tacky men drinking pints of best bitter pull girls in white high heels and Miss Selfridge’s miniskirts.’

Towards the middle of 1989, in the wake of extensive newspaper coverage of acid house culture, clubbers began to talk of a new mainstream – or rather, at first, it was described as a second-wave of media-inspired, sheep-like acid house fans. This culture was populated by ‘mindless ravers’ or ‘Acid Teds’. Teds were understood to travel in same-sex mobs, support football teams, wear kickers boots and be ‘out of their heads’. Like Sharon and Tracy, they were white, heterosexual and working-class. But unlike the girls, the ravers espoused the subterranean values proper to a youth culture (like their laddish namesakes, the Teds or Teddy Boys of the fifties) at least in their predilection for drugs, particularly Ecstasy or ‘E’.

However, when the culture came to be positioned as truly ‘mainstream’ rather than just behind the times, it was feminized. This shift coincided with the dominance of house and techno (with titles like Hardcore Ecstasy, Awesome 2 and Steamin! – Hardcore ‘92) in the compilation album top twenty throughout 1990, 1991 and 1992. By the end of this period, talk of ‘Acid Teds’ was superseded by disparagement of raving Sharons and ‘Techno Tracys’. The music genre had even come to be called ‘handbag house.’ As one clubber explained to me, ‘The rave scene is dead and buried. There is no fun in going to a legal rave when Sharons and Tracys know where it is as soon as you buy a ticket.’ Consumer magazines ran spoof columns, ‘Six of the best ways to be a Techno Tracy’, which advised readers to ‘discard your 25-carat gold chains in favour of a crystal pendant’ and ‘laugh at the girls you’ve left behind at the local disco, because “they just don’t understand good music”‘ (Face November 1991).

Some clubbers and ravers might want to defend these attitudes by arguing that the music of Stock/Aitken/Waterman, then acid house-cum-techno, respectively dominated the charts in 1987–8, and then in 1989–91. But there are a couple of problems with this reasoning. First, the singles’ sales chart is mostly a pastiche of niche sounds which reflect the buying patterns of many taste cultures rather than a monolithic mainstream (cf. Crane 1986). Moreover, buyers of the same records do not necessarily form a coherent social group. Their purchase of a given record may be contextualised within a very different range of consumer choices; they may never occupy the same social space; they may not even be clubbers.

Second, whether these ‘mainstreams’ reflect empirical social groups or not, they exhibit the burlesque exaggerations of an imagined other. Teds and Tracys, like lager louts, sloanes, preppies and yuppies, are more than euphemisms of social class and status, they demonstrate ‘how we create groups with words’ (Bourdieu 1990: 139). So, the activities attributed to ‘Sharon and Tracy’ should by no means be confused with the actual dance culture of working-class girls. The distinction reveals more about the cultural values and social world of hardcore clubbers because, to quote Bourdieu again, ‘nothing classifies somebody more than the way he or she classifies’ (Bourdieu 1990: 132).

It is precisely because the social connotations of the mainstream are rarely examined that the term is so useful; clubbers can denigrate it without self-consciousness or guilt. However, even a cursory analysis reveals the relatively straightforward demographics of these personifications of the mainstream. Firstly, the clichés have class connotations. Sharon and Tracy, rather than, say, Camilla and Imogen, are what sociologists have tended to call ‘respectable working-class’. They are not imagined as poor or unemployed, but as working and aspiring. Still, they are not envisaged as beneath ‘hip’ clubbers as much as being classed full stop. In other words, they are trapped in their class. They do not enjoy the classless autonomy of ‘hip’ youth.

Age, the dependence of childhood and the accountabilities of adulthood are also signalled by the mainstreams. The recurrent trope of the handbag is something associated with mature womanhood or with pretending to be grown-up. It is definitely not a sartorial sign of youth culture, nor a form of objectified subcultural capital, but rather a symbol of the social and financial shackles of the housewife. The distinction between the authentic original and the hanger-on is also partly about age – the connoisseur deplores the naive and belated enthusiasm of the younger raver or, conversely, the younger participant castigates the tired passions of the older one for holding on to a passé culture.

Young people, irrespective of class, often refuse the responsibilities and identities of the work world, choosing to invest their attention, time and money in leisure. In his classic article ‘Age and sex in the social structure of the United States’, Talcott Parsons argues that young people espouse a different ‘order of prestige symbols’ because they cannot compete with adults for occupational status (Parsons 1964: 94). They focus less on the rewards of work and derive their self-esteem from leisure – a sphere which is more conducive to the fantasies of classlessness which are central to club and rave culture. In Distinction, Bourdieu identifies an analogous pattern solely for French middle-class youth. ‘Bourgeois adolescents,’ he writes, ‘who are economically privileged and (temporarily) excluded from the reality of economic power, sometimes express their distance from the bourgeois world which they cannot really appropriate by a refusal of complicity whose most refined expression is a propensity towards aesthetics and aestheticism’ (Bourdieu 1984: 55).

A refusal of complicity might be said to characterize British youth culture in general. Having loosened ties with family but not settled with a partner nor established themselves in an occupation, youth are not as anchored in their social place as those younger and older than themselves. By investing in leisure, youth can further reject being fixed socially. They can procrastinate what Bourdieu calls ‘social ageing’, that ‘slow renunciation or disinvestment’ which leads people to ‘adjust their aspirations to their objective chances, to espouse their condition, become what they are and make do with what they have’ (Bourdieu 1984: 110–11). This is one reason why youth culture is often attractive to people well beyond their youth. It acts as a buffer against social ageing – not against the dread of getting older, but of resigning oneself to one’s position in a highly stratified society.

The material conditions of youth’s investment in subcultural capital (which is part of the aestheticized resistance to social ageing) results from the fact that youth, from many class backgrounds, enjoy a momentary reprieve from necessity. According to Bourdieu, economic power is primarily the power to keep economic necessity at bay. This is why it ‘universally asserts itself by the destruction of riches, conspicuous consumption, squandering and every form of gratuitous luxury’ (Bourdieu 1984: 55). But ‘conspicuous’, ‘gratuitous’ and ‘squandering’ might also describe the spending patterns of the young. Since the 1950s, the ‘teenage market’ has been characterized by researchers as displaying ‘economic indiscipline’. Without adult overheads like mortgages and insurance policies, youth are free to spend on goods like clothes, music, drink and drugs which form ‘the nexus of teenage gregariousness outside the home’ (Abrams 1959: 1).

Freedom from necessity, therefore, does not mean that youth have wealth so much as that they are exempt from adult commitments to the accumulation of economic capital. In this way, youth can be seen as momentarily enjoying what Bourdieu argues is reserved for the bourgeoisie, that is the ‘taste of liberty or luxury’. British youth cultures exhibit that ‘stylization of life’ or ‘systemic commitment which orients and organizes the most diverse practices’ that develops as the objective distance from necessity grows (Bourdieu 1984: 55–6).

This is true of youth from all but the poorest sections of the population, perhaps the top seventy-five per cent. While youth unemployment, homelessness and poverty are widespread, there is still considerable discretionary income amongst the bulk of people aged 16–24. The ‘teenage market’, however, has long been dominated by the boys. In the 1950s, 55 per cent of teenagers were male because girls married earlier, and 67 per cent of teenage spending was in male hands because girls earned less (cf. Abrams 1959). In the 1990s, the differential earnings of young men and women have little changed – a fact which no doubt contributes to the masculine bias of subcultural capital.

Although clubbers and ravers loathe to admit it, the femininity of these representations of the mainstream is hard to deny. In fact, consistently over the past two decades, more girls have gone out dancing than boys. This is particularly marked amongst the sixteen-to-nineteen age-group because girls start clubbing at a younger age. Dancing is, in fact, the only out-of-home leisure activity that women engage in more frequently than men. Men are ten times more likely to attend a sporting event, twice as likely to attend live music concerts and marginally more inclined to visit the cinema (Central Statistical Office General Household Surveys 1972–86). When it comes to preferences rather than the practices, gender is again decisive; the first choice for an evening out for women between fifteen and twenty-four is a dance club whereas the most popular choice of men the same age is a pub (Mintel 1988b).

Girls and women are also more likely to identify their taste in music with pop. Over a third of women (of all ages), compared to about a quarter of men, say it is their favourite type of music. Women spend less time and money on music, the music press and going out, and more on clothes and cosmetics (Mintel 1988c; Euromonitor 1989). One might assume, therefore, that they are less sectarian and specialist in relation to music because they literally and symbolically invest less in their taste in music and participation in music culture.

In their American study, Christenson and Peterson found marked gender differences in attitudes to the ‘mainstream’ amongst American youth. Their research suggested that men regarded the label mainstream as ‘essentially negative, a synonym for unhip’ whereas women understood it as ‘another way of saying popular music’ (Christenson and Peterson 1988: 298). Their women respondents were more likely to say that they used music ‘in the service of secondary gratifications (e.g. to improve mood, feel less alone) and as a general background activity’. They conclude by describing the male use of music as ‘central and personal’ and the female orientation to music as ‘instrumental and social’ (Christenson and Peterson 1988: 299). These American findings about women’s use of music correlate with British clubbers’ assumptions about the mainstream.

The objectification of young women, entailed in the ‘Sharon and Tracy’ image, is significantly different from the ‘sluts’ or ‘prudes’, ‘mother’ or ‘pretty waif frameworks typically identified by feminist sociologists (cf. Cowie and Lees 1981; McRobbie 1991). It is not primarily a vilification or veneration of girls’ sexuality (although that gets brought in), but a position statement made by youth of both genders about girls who are not culturally ‘one of the boys’. Subcultural capital would seem to be a currency which correlates with and legitimizes unequal statuses.

These mainstreams also point to the relevance of Andreas Huyssen’s arguments about how mass culture has long been positioned as feminine by high cultural theorists, but here the traditional divide between virile high art and feminized low entertainment is replayed within popular culture itself (cf. also Modleski 1986a and Morris 1988). Even among youth cultures, there is a double articulation of the lowly and the feminine: disparaged other cultures are characterized as feminine and girls’ cultures are devalued as imitative and passive. Authentic culture is, by contrast, depicted in gender-free or masculine terms and remains the prerogative of boys.

The refusal of parental class and work culture goes some way towards explaining why young people seem to borrow tastes and fashions from gay and black cultures. Jon Savage has argued that the camp and kitsch sensibilities of gay male culture have been repeatedly taken up by British youth (cf. Savage 1988). Stephen Lee has argued that, in an American context, the trendy club scene often maintains its esotericism by hiding in gay clubs and drawing from gay cultures which threaten the college ‘jocks’. More often noted (and arguably more relevant to club cultures in this period) is British youth’s habit of borrowing from African-American and Afro-Caribbean culture – often with a romantic, ‘orientalist’ appropriation of black cultural tropes (cf. Hebdige 1979; Said 1985). Even the word ‘hip’ is said to have its origins in black ‘jive talk’ where the phrase ‘to be on the hip’ initially meant that one was an opium smoker but was later generalized to mean simply being ‘in the know’ (Polsky 1967).

Subcultural capital is the linchpin of an alternative hierarchy in which the axes of age, gender, sexuality and race are all employed in order to keep the determinations of class, income and occupation at bay. Interestingly, the social logic of subcultural capital reveals itself most clearly by what it dislikes and by what it emphatically isn’t. The vast majority of clubbers and ravers distinguish themselves against the mainstream. In the final section of this chapter, I discuss some of the methodological problems involved in mapping the cultural organization of clubs, given the specific social agendas to which clubber representations of the clubworld are put.

Participation versus Observation of Dance Crowds

One complication of my fieldwork resulted from the fact that the two methods that make up ethnography – participation and observation – are not necessarily complementary. In fact, they often conflict. As a participating insider, one adopts the group’s views of its social world by privileging what it says. As an observing outsider, one gives credence to what one sees. In this case, the results of the two methods contrasted dramatically. The ‘mainstream’ was a perennial point of discursive reference, perpetually absent from view.

This methodological contradiction between participation and observation is best understood within the larger epistemological conflict which Bourdieu discusses in terms of subjectivism and objectivism. As John Thompson aptly summarizes, subjectivism is an ‘intellectual orientation to the social world which seeks to grasp the way the world appears to individuals within it’; it explores people’s beliefs and ignores the unreliability of their conceptions. Objectivism, by contrast, is an approach to the social world which ‘seeks to construct the objective relations which structure practices and representations’; it explains life in terms of material conditions and ignores the experience individuals have of it (Thompson 1991: 11). According to Bourdieu, both modes of thought are too onesided to describe adequately the social world. On their own, neither approach can come to grips with the double nature of social reality. On the one hand, social life is determined by material conditions but, on the other, these conditions affect behaviour through the intercession of beliefs and tastes. In the previous section, I investigated the subjective social worlds of clubbers and ravers; in this one, I pursue a more objectivist line of inquiry.

Between 1988 and 1992, I acted as a participant observer at over two hundred discos, clubs and raves and attended at least thirty live gigs for comparative purposes. In the course of these four years’ ethnographic research, I was unable to find a crowd I could comfortably identify as typical, average, ordinary, majority or mainstream. Not that I didn’t witness people dancing to ‘chartpop’ or to techno music at raves. On the contrary, I observed all sorts of different configurations of these crowds. Several times, I even observed the old and the new mainstreams together in the same room. At a Glasgow club in the spring of 1989, for example, the music alternated between Stock/Aitken/Waterman and what had just ceased to be called ‘acid house’ (because of mass media overexposure). The population and practices of the dancefloor fluctuated according to the shift of genres, going from being almost entirely female to mostly male, from soulful free-form dancing in pairs to ecstatic trance-dancing in groups of six and eight. But I also observed a multitude of other cultural configurations. To apply the label ‘mainstream’ to any of these would have run the risk of denigrating or normalizing the crowd in question. I could always find something that distinguished them – if not local differences, then shades of class, education and occupation, gradations of gender and sexuality, hues of race, ethnicity or religion.

Ethnography is a qualitative method that is best suited to emphasizing the diverse and the particular. The mainstream, by contrast, is an abstraction that assumes a look of generality and a quantitative sweep. Participant observation is not equipped to establish whether a particular dance crowd is nationally dominant unless, of course, it is mass-observation proposing to collect and quantify the work of many researchers. (For this reason, as mentioned above, it is rather incredible that Mungham (1976) professes to offer an ethnography of mainstream dancing by doing research in a single dancehall.) My method was one of ethnographic survey, rather than the more common ethnographic case study, which meant that representativeness was a particular concern. I consulted government statistics and market research but because their data on dancing tends to be either incomplete or very general, I was unable to construct a convincing random sample of clubs. Nevertheless, I did discover material that helped me to assemble a more objectivist picture of club culture, particularly with regard to the site that has been consistently identified as the location of the mainstream by dance crowds and academics alike – the Mecca disco.

In 1990, Mecca owned fifty-eight out of an estimated four thousand nightclubs in Britain. Publicly listed leisure corporations own just five per cent of British clubs – a situation dramatically different from that of, say, the record industry where the five majors are generally responsible for seventy per cent of annual sales. Unlike other nightclub operators, Mecca (which has since been taken over by Rank Leisure) promoted its clubs under four hierarchically ranked brands: their two main chains, Ritzy and 5th Avenue, their so-called ‘smaller, more intimate and exclusive brand’, Cinderella Rockerfellas, and their flagship venue, The Palais in Hammersmith. In 1992, however, they came to realize that their branding policy was backfiring. Marketers in other kinds of business are usually keen to be perceived as ‘mainstream’; they are particularly intent for their brand name to become generic for all products of the same kind – in the manner of, say, Biro, Hoover or Kleenex. However, as Mecca-Rank discovered rather belatedly, generics are anathema to club culture. Their active branding had actually facilitated their negative positioning as the mainstream. As Mintel reported it, ‘Rank does not see any advantages of nationwide branding in this market’, so the company abandoned the unifying brands’ concept and renamed each of their venues individually (Mintel 1992).

Although big business is often aligned with mass culture, the empirical grounds for the association in this case are slim. Mecca ‘chartpop’ disco culture would seem to be yet another niche culture – one positioned as the norm, partly because of Mecca’s long history and its misguided business strategies. Moreover, the youth cultures housed by Mecca clubs are not, and have never been, homogeneous. Despite their centralized operations, Mecca dancehalls have long been the home of traditional spectacular subcultures. For example, Tottenham Mecca was a key Teddy Boy hang-out in the 1950s and Blackpool Mecca was one of the main hubs of the Northern Soul scene in the 1970s. In the late eighties, the Hammersmith Palais frequently played host to Banghra events.

In distributing my participant observation, I was certain to attend Mecca venues and mixed-genre ‘chartpop’ clubs, but I also did my best to explore a balance of black and white, gay and straight, student and non-student clubs and raves. I was concerned to investigate a broad range of musical styles: from rock’n’roll revival through classic disco to new age cyberpunk clubs; from clubs with reggae, rare groove and hiphop playlists to ones featuring indie, industrial and rock music. Nevertheless, the balance of my research was tipped in favour of the house–techno–rave continuum which did seem to eclipse other club sounds during the period in question. My study also had a distinct urban bias. Most of my research was carried out in London, with substantial preliminary research conducted in Glasgow. Although I visited clubs around the country, from the Haçienda in Manchester to Bobby Brown’s in Birmingham, this work was complementary rather than core.

As I mentioned in the Introduction, being foreign had some research advantages. It was easier to approach and to obtain information from strangers, particularly in as much as they were more likely to explain the obvious. Moreover, British ideologies about the mainstream baffled me where they might have been taken for granted by a British researcher. They were a puzzle that I was determined to resolve. After much questioning, it turned out that many clubbers who disparaged the mainstream confessed that they had never attended such a dance club. Moreover, their use of a limited repertoire of cultural details, metaphors and metonyms suggested that their knowledge of these other crowds was mostly second-hand, either heard along grapevines or gathered from media sources. Both mainstreams were, in fact, closely associated with specific media texts. The ‘dancing around handbags’ crowd was imagined principally as an enthusiastic audience of Top of the Pops (for over twenty-five years, the key point of television exposure for the singles sales chart); as one clubber put it, these clubs were full of people who ‘think Top of the Pops is trend-setting’. This crowd was also identified with a late-night programme called The Hitman and Her presented by Pete Waterman of the production trio, Stock/Aitken/Waterman; as another clubber explained, ‘chartpop’ discos were ‘full of the Hitman and Her elements’. (It is worth noting that many of Pete Waterman’s Hitman and Her television shows were shot on location in Mecca venues and that Waterman-produced artists, Kylie Minogue and Jason Donovan, did their initial national ‘public appearance’ tours in Mecca discos.) Acid Teds and Techno Tracys, by contrast, were often characterized as Sun readers (the widest-read daily paper in the world, with a circulation which hovers around four million).

In contemporary Britain, the media are bound to be an important source of information about other social groups and, consequently, a means of orientating oneself in the social world. Like its ancestor the ‘mass’, it would seem that the mainstream is, to a large extent, read off media texts. Theodor Adorno associated the worst tendencies of mass culture with the ‘radio generation’ much as David Riesman defined his indiscriminate majority as ‘the audience for the larger radio stations and the hit parade’; so club crowds conceive their mainstreams with the aid of national television and tabloids (Adorno 1941/1990: 40; Riesman 1950/1990: 8). This process maybe common to other interest groups, but it is inflected by the youthful commonsense that club culture is the inverse of broadcasting’s domestic accessibility and that it is the antithesis of widely disseminated tabloid talk.

The concept of the mainstream grows out of the inextricability of the media and lived culture. For this reason, it is no wonder that the consensus in North America is that the mainstream is a cluster of subcultures (cf. Crane 1986; Grossberg 1987; Straw 1991). The size, ethnic diversity and proliferation of local, regional and niche media in the United States weaken the myth of the ‘mainstream’. Whereas, in the United Kingdom, the ‘mainstream’ is a more powerful idea to youth and academics alike not only because of a predominately white and Anglo-Saxon population, but also due to the primacy of national mass media centralized in London. (This is explored in depth in the next chapter.)

So how are club crowds objectively organized? First, it is worth emphasizing that ‘crowd’ is the word used by clubbers and ravers to describe the collections of people who go out dancing. It is an appropriate term for it implies a congregation of limited time and unity, but leaves the exact structure open to further definition; crowds may contain a nucleus of regulars, degrees of integration and clusters of cliques. Unlike the ‘mass’, they are local and splintered. Crowds are the building-blocks of club cultures and, until the day when communications media offer multi-sensory interaction in the form of a fully virtual reality nightclub, it is likely that such congregations will be important to many kinds of music scene, community and culture.

Pre-eminently, crowds act as a concrete reminder that any analysis of the cultural organization of youth needs to take into account the social groups to which they belong. In subcultural studies, the spatial and social existence of youth cultures have often been lost under the symbolic weight of their clothes and their consumer habits. Despite scholars’ claims that subcultures are ‘not simply ideological constructs’, empirical social groups have often been elided. (Clarke et al. 1976: 46) This is true not just of 1970s subcultural studies, but of recent work in the field. In his otherwise compelling article, ‘Systems of articulation, logics of change: Communities and scenes in popular music’, for example, Will Straw maps out two communities – the North American dance music and heavy metal scenes – with little reference to the people who inhabit or imagine them. Whether the people actually gather is irrelevant. Despite use of the term ‘community’, the communal is all but ignored. Even the nature of the differences between the communities as subjectively imagined and objectively practised is eclipsed by an implicit notion that it is all discourse.

One function of a disparaged other like the mainstream is to contribute to the feeling of community and sense of shared identity that many people report to be the primary appeal of clubs and raves. As clubbers and ravers explain:

It is so wicked to go somewhere and be surrounded by loads of people your own age and into the same stuff – the last time you had that it was at school, but that wasn’t through choice!

The appeal of clubs comes down to people who you would like to surround yourself with. Being with people who are similar to yourself creates a feeling of belonging …

The thrill (and it really is a thrill) of going to clubs is the communal experience, the feeling of sharing something with other like-minded people.

The feeling of belonging can override obvious social differences. A straight woman who goes dancing only in gay men’s clubs writes:

I tell my [boyfriend] that this is my private – among two thousand people – freak out session… I do not want him to come with me when I go out dancing… this is one place that is my place… I love to wander around the club and feel unthreatened by being female.

Many clubbers talk about the rightness and naturalness of the crowds in which they have had good experiences. They feel that they fit in, that they are integral to the group. The experience is not of conformity, but of spontaneous affinity. ‘Good’ clubs are full of familiar strangers who complement that ‘well developed leisure activity, the discovery of self’ (Dorn and South 1989: 179).

Despite being ‘similar’ and ‘like-minded’, when asked to describe the social character of the crowd at the clubs they attend, clubbers are inclined to say they are ‘mixed’. Just as other crowds are assumed to be homogeneous, so their own crowds are perceived as heterogeneous. Nevertheless, most clubs have observable ‘master statuses’. In his article, ‘The dilemmas and contradictions of status’, Everett Hughes argues that race, sexuality, class and professional standing take on different precedence in different contexts (cf. Hughes 1945). So, different clubs contextualize social differences in different ways: in one sexual identity is primary; in another racial or occupational identity unify the crowd.

Although no one social difference is paramount in all clubs, the axis along which crowds are most strictly segregated is sexuality – a fact which betrays the importance of clubs as a place for people to meet prospective sexual partners whether they are gay or straight. This separation was perhaps more extreme between 1988 and 1992 than in other periods. The New Romantic, ‘gender-bending’ clubs of the early 1980s were reported to be sexually mixed. The late 1980s saw a decline in clubs where gay, bisexual and straight people socialized perhaps because of the rise of AIDS and anti-gay legislation like Clause 28 and 29 which led to both increased separatism on the part of the gay community and also to intensified homophobia on the part of young heterosexuals. However, a vogue for cross-dressing clubs like Kinky Gerlinky in 1991–2 and a mildly sexually experimental mod revival in 1993–4 were signs that this was again shifting. Nevertheless, sexuality is a perennial divider. Most listing magazines catalogue dance clubs together in a single section, except for gay and lesbian clubs which are put in a completely different part of the magazine under rubrics like ‘Gay’ or ‘Out in the City’.

After sexuality, the second most important factor determining who congregates where is taste in music. Clubbers and ravers generally explain their attendance at particular events in terms of their love of the music played. The centrality of music is further indicated by the fact that amongst the information on flyers promoting clubs, music is the only cultural attribute that is almost always mentioned. Usually the music is specified by a short generic list: for example, ‘techno, hardcore, alternative, trance’ or ‘ragga-hiphop-jungle’. The music is also invoked by naming DJs who are associated with certain sounds and crowds. (In the case of indie clubs, which experience their apogee elsewhere at gigs and revolve around bands, the music is often specified by an exhaustive catalogue of the artists played, e.g. ‘The Charlatans, Happy Mondays, Farm, Stone Roses …’ or ‘Blur, Pulp, Suede, Oasis’ etc.) By whichever means the music is conjured, it relates directly to the promised crowd because taste is not, of course, an individual matter.

Musical preference has a complicated and contingent but unmistakable relation to the social structure. As George Lewis succinctly explains, ‘we pretty much listen to, and enjoy, the same music that is listened to by other people we like or with whom we identify’ (Lewis 1992: 137). Bourdieu argues that next to taste in food, taste in music is the most ingrained. Aesthetic appreciation is passionate (people love their music) and aesthetic intolerance violent (they hate that noise) perhaps because aural experiences take firmer root in the body than, say, visual ones. Although socially conditioned, musical taste is experienced as second nature. It is felt to be involuntary, instinctive, visceral. As a deep-seated taste dependent on background, music preference is therefore a reasonably reliable indicator of social affinity.*

Although taste usually ensures that the appropriate crowd turns up at the right venue on a given night, door policies also regulate the crowd. Here, the first set of differences crucial to admission relate to the body. Policies that involve age, gender and sexuality are often explicitly administered. Door staff will tell people waiting outside a club that three men and a woman are more likely to get into a straight club than an all-male group and that women in general are favoured. The staff will also inform punters that they are too old or occasionally too young for the place, while doormen at gay clubs will warn or question men whose body language appears too heterosexual. Refusing entry to a gay man at a straight club, however, is likely to employ the excuse of dress, just as discrimination against youth of African or Asian descent is never openly acknowledged. Ratios of black to white patrons are often carefully managed, frequently by black bouncers. (For an analysis of the way clubs employ black bouncers to implement racist door policies, cf. Mungham 1976.) Usually the alibi here is clothes. For example, in the summer of 1989, a trendy house music club in a black neighbourhood conducted a strict ban on trainers (running shoes) which had the effect of admitting the Doc-Martens-wearing white kids and excluding the Nike-wearing Afro-Caribbean kids at a moment when white youth were less likely to sport a hiphop-influenced wardrobe.

Self-selection is the first principle in the organization of club crowds; routes of communication (discussed in the next chapter) is the second; door policy is the third. Door people put the finishing touches to the composition of the crowd. They style the club’s internal image and contribute to its cohesive total environment. As such, they are key readers and makers of the ‘meaning of style’. Most analysts of subcultural style have de-contextualised clothes and overlooked the role of the situated viewer (cf. Hebdige 1979; Wilson 1985). Rather than privileging their own free-wheeling interpretations, these critics could keep the clothes in situ and anchor their discussions of sartorial meaning in key social interactions like those of the club.

Some clubbers liken getting through the door to passing an exam: one needs to study the look, prepare the body and stay cool under pressure. This does not mean that club crowds are stylistically or superficially similar rather than substantially alike. Clothing is a potent indicator of social aspiration and position; as Tom Wolfe once put it, ‘fashion is the code language of status’ (Wolfe 1974: 23). As forms of objectified subcultural and economic capital, clothes frequently act as metonyms for larger social strata. ‘Blue collar’ and ‘white collar’ are euphemisms for class, just as references to stilettos and handbags are roundabout ways of saying that a social group lacks subcultural capital.

Conclusion

Whatever its exact status, the mainstream is an inadequate concept for the sociology of culture. References to the mainstream are often a way of deflecting issues related to the definition and representation of empirical social groups. Sometimes, it signals an unquestioning acceptance of youth’s point of view or rather the universalization of the embodied social structure of a particular group. On other occasions, the binary thinking which accompanies references to the mainstream is entangled in a series of value judgements, political associations and journalistic clichés which hardly do justice to the youth cultures in question. Their schemas (like the youthful ideologies they reproduce) mix and match oppositions such as the following:

| US | THEM |

| Alternative | Mainstream |

| Hip /cool | Straight / square / naff |

| Independent | Commercial |

| Authentic | False / phoney |

| Rebellious / radical | Conformist / conservative |

| Specialist genres | Pop |

| Insider knowledge | Easily accessible information |

| Minority | Majority |

| Heterogeneous | Homogeneous |

| Youth | Family |

| Classless | Classed |

| Masculine culture | Feminine culture |

Popular ideologies about dance crowds are riddled with implied statuses, refined echelons and subcultural capitals. Rather than subverting dominant cultural patterns in the manner attributed to classic subcultures, these clubber and raver ideologies offer ‘alternatives’ in the strict sense of the word, namely other social and cultural hierarchies to put in their stead. They may magically resolve certain socio-economic contradictions, but they also maintain them, even use them to their advantage. For many youthful imaginations, the mainstream is a powerful way to put themselves in the big picture, imagine their social world, assert their cultural worth, claim their subcultural capital. As such, the mainstream is a trope which betrays how beliefs and tastes which ensue from a complex social structure, in turn, determine the shape of social life. This is the ‘double nature’ of social reality.