4

The Media Development of ‘Subcultures’ (or the Sensational Story of Acid House)

The Underground versus the Overexposed

The idea that authentic culture is somehow outside media and commerce is a resilient one. In its full-blown romantic form, the belief suggests that grassroots cultures resist and struggle with a colonizing mass-mediated corporate world. At other times, the perspective lurks between the lines, inconspicuously informing parameters of research, definitions of culture and judgements of value. Either way, theorists and researchers of music and youth culture are among the most tenacious holders of the idea. This chapter, however, contends that the distinctions of youth subcultures are, in many cases, phenomena of the media.

Every music scene has its own distinct set of media relations. ‘Acid house’, a dance club culture which mutated into ‘rave’ after sensational media coverage about drug use, is particularly revealing of the cultural logics involved. In considering this case, I argue that there is, in fact, no opposition between subcultures and the media, except for a dogged ideological one. I do not uncover pure origins or organic homologies of sound, style and ritual, nor vilify a vague monolith called ‘the media’. Instead, I examine how various media are integral to youth’s social and ideological formations. Local micro-media like flyers and listings are means by which club organizers bring the crowd together. Niche media like the music press construct subcultures as much as they document them. National mass media, such as the tabloids, develop youth movements as much as they distort them. Contrary to youth subcultural ideologies, ‘subcultures’ do not germinate from a seed and grow by force of their own energy into mysterious ‘movements’ only to be belatedly digested by the media. Rather, media and other culture industries are there and effective right from the start. They are central to the process of subcultural formation, integral to the way we ‘create groups with words’ (Bourdieu 1990: 139).

The term ‘underground’ is the expression by which clubbers refer to things subcultural. More than fashionable or trendy, ‘underground’ sounds and styles are ‘authentic’ and pitted against the mass-produced and mass-consumed. Undergrounds denote exclusive worlds whose main point may not be elitism but whose parameters often relate to particular crowds. They delight in parental incomprehension, negative newspaper coverage and that best blessing in disguise, the BBC ban. More than anything else, then, undergrounds define themselves against the mass media. Their main antagonist is not the law which might suppress but the media who continually threaten to release their knowledges to others.

Like ‘subcultures’, undergrounds are nebulous constructions. They can refer to a place, a style, an ethos, and their crowds usually shun definitive social categorization. Mostly they are said to be ‘mixed’ but, although the subcultural discourses I describe do cross lines of class, race and sexuality, their holders are less likely to physically cross the relevant thresholds (see previous chapter). Generally, underground crowds are attached to sounds. As one label manager put it: ‘There are records out there that are more radical and, at this moment, have a more radical audience – a smaller, more selective audience – but the sounds in that area will be the next generation of sounds we’re all used to … That’s what I mean by underground’ (Select July 1990: 57).

The logic of the underground is aptly symbolized by its attitude to two product types. Its distinctive format is the ‘white label’ – a twelve-inch single produced in a limited edition without the colourful graphics that accompany most retailed music, distributed to leading disc jockeys for club play and to specialist dance record shops for commercial sale. The rarity of white labels guarantees their underground status, while accumulating them can contribute to their owner’s distinction. (The size of a man’s record collection has long been a measure of his subcultural capital!) At the other end of the spectrum, the format with the least credibility is the television-advertised compilation album of already charted dance hits. One fanzine writer ranted against amateur ravers who buy such albums: ‘Wise up sucker, get hip to musical freedom, stop investing in K-Tel compilations with titles like Nonstop Mental Mega Chart Busting Ravey Rip Off Hits Vol 234516’ (Herb Garden December 1991). While these hit compilations may contain music that was on a white label only six months earlier, the sounds are corrupted by being accumulated and packaged.

The underground espouses a fashion system that is highly relative; it is all about position, context and timing. Its subcultural capitals have built-in obsolescence so that it can maintain its status not only as the prerogative of the young, but the ‘hip’. This is why the media are crucial; they are the main disseminators of these fleeting capitals. They are not simply another symbolic good or indicator of distinction, but a series of institutional networks essential to the creation, classification and distribution of cultural knowledge.

Before going on to survey relations between the dance ‘underground’ or subculture and various media, I should explain that this part of my work is based on several different methods of research. First, it derives from my ethnographic research in clubs; I was careful to pay heed to passing comments, and to question clubbers, about their use of and attitudes towards diverse media. So, rather than a study of reception per se, this chapter offers an analysis of the larger site of media consumption. Second, it draws on interviews with professionals in the field – particularly club organizers, journalists and record company PR and promotions people. Finally, it is based on a extensive textual analysis of the media under consideration. This unorthodox combination of methods was necessary to give a fuller picture of the myriad relations between club cultures and the media.

I should also clarify how my approach is indebted to and critical of four existing accounts of the relationship between youth, music and media. First, it diverges on several key points from the cultural studies associated with the Birmingham tradition. In the Introduction to Resistance through Rituals, Clarke et al. suggest that their consideration of post-war youth subcultures will ‘penetrate beneath [the] popular constructions’ of the mass media (Hall and Jefferson 1976: 9). When they come to define ‘subculture’, they position the media and its associated processes outside, in opposition to and after the fact of subculture. In so doing, they omit precisely that which clearly delineates a ‘subculture’, for labelling is crucial to the insiders’ and outsiders’ views of themselves as different. By discarding this key symbolic interactionist insight, their classification of subculture is indeterminate (cf. Becker 1963). Subcultures are said to have a ‘distinctive enough shape and structure to make them identifiably different’; they are ‘focused around certain activities, values … territorial spaces’ and can be either ‘loosely or tightly bounded’ (Hall and Jefferson 1976: 13–14). This definition could be applied to many cultural groups.

The Birmingham tradition tended to study previously labelled social types – ‘Mods’, ‘Rockers’, ‘Skinheads’, ‘Punks’ – but gave no systematic attention to the effects of various media’s labelling processes. Instead, they described the rich and resistant meanings of youth music, clothing, rituals and argot in a miraculously media-free moment when an uncontaminated homology could be safely identified. Moreover, the Birmingham tradition frequently positioned subcultures as transparent niches in an opaque world as if subcultural life spoke an unmediated truth. They were insufficiently critical of subcultural ideologies, first, because their attention was concentrated on the task of puncturing and contesting dominant ideology and, second, because their theories agreed with the anti-mass media discourses of youth music cultures. While youth celebrated the ‘underground’, the academics venerated ‘subcultures’; where one group denounced the ‘commercial’, the other criticized ‘hegemony’; where one lamented ‘selling out’, the other theorized ‘incorporation’.

Sociologies of ‘moral panic’, a second academic tradition that addresses the subject of youth cultures and the media, contrast with the cultural studies on several key points (cf. Cohen 1972/1980; Young 1971; Cohen and Young 1973). While the subculturalists depict full-blown subcultures without any media intervention, scholars of ‘moral panic’ assume that little or nothing existed prior to mass media labelling. So, in his classic Folk Devils and Moral Panics, Stanley Cohen suggests that there were few antagonisms between Mods and Rockers, nor even thoroughly articulated stylistic differences, before reports of their seaside scuffles (cf. Cohen 1972/1980). Also, while the subculturalists are implicitly indebted to the youth-oriented music and style press, the ‘moral panic’ scholars often seem unaware of their existence. In Cohen’s book, for instance, the media is synonymous with local and national newspapers, while magazines which might have been read by his subcultural subjects are ignored (i.e. the Mod girl’s Honey or the Mod boy’s Record Mirror).*

Sociologies of ‘moral panic’ offer important theories of deviance amplification, self-fulfilling prophecies and composite stereotypes called ‘folk devils’, but they do not take a sufficiently sweeping look at associated processes of cultural production and consumption. According to Cohen, ‘folk devils’ are ‘unambiguously unfavourable symbols’ but a devil in the tabloids is often a hero or, more commonly, an idiot in the youth press (cf. Cohen 1972/1980). The negative tabloid coverage of acid house, for example, was subject to extensive analysis by the music and style magazines. The writers were fascinated by their own representation and, however much they condemned the tabloids, they revelled in the attention and boasted about sensational excess. What could be a better badge of rebellion? Mass media misunderstanding is often a goal, not just an effect, of youth’s cultural pursuits. As a result, ‘moral panic’ has become a routine way of marketing popular music to youth.

Ethnographies of music scenes, like subcultural studies, tend to see the media as outside authentic culture (cf. Finnegan 1989; Cohen 1991). They depict internally generated culture, disclose local creativity and give positive valuation to the ‘culture of the people’ but only at the cost of removing the media from their pictures of the cultural process. When media are theorized by traditional ethnographies, they are generally seen as akin to the ethnographer’s own representational practice, as depicting and disseminating the culture in question (cf. Clifford and Marcus 1986). But media sights, sounds and words are more than just representations; they are mediations, integral participants in music culture. Needless to say, there are no primordial pre-media cultures in Britain today. Even when a youth culture defines itself against the overexposed entertainments of the Sun or the prime-time pleasures of Top of the Pops, its identity and activities are conditioned by the desire to be part of something that is not widely distributed or televised.

This is not to posit the reverse, postmodern ‘ecstasy of communication’ proposition, in either its euphoric or mournful incantation. Visions of endless mediascapes are as wilfully one-sided as the anthropologist’s dream of pure culture. Iain Chambers’s cruise through ‘the communication membrane of the metropolis’, for instance, does little to clarify the concrete relations between youth and music cultures and their various media. When we are said to have screens for eyes and headphones for ears, then communication is automatic, indiscriminate and total (cf. Chambers 1986). But access to information is restricted at every turn. We are not all plugged in, so to speak, and certainly not into some central bank of sight and sound. In fact, being ‘hip’ or ‘in the know’ is testimony to the very selective nature of contemporary communications; ‘subcultural capital’ is defined against the supposedly obscene accessibility of mass culture (cf. Baudrillard 1982).

To understand the relations between youth subcultures and the media, one needs to pose and differentiate two questions. On the one hand, how do youth’s subcultural ideologies position the media? On the other, how are the media instrumental in the congregation of youth and the formation of subcultures? The two questions are entwined but distinct. Youth’s ‘underground’ ideologies imply a lot but understand little about cultural production. Their views of the media have other agendas to fill. Like other anti-mass culture discourses, they are not always what they purport to be, i.e. politically correct, moral or vanguard. As discussed in the previous chapter, subcultural ideologies are a means by which youth imagine their own and other social groups, affirm their distinction and confirm that they are not just ‘attention spans’ to be bought and sold by advertisers.

Similarly, the second question about how the media do not just represent but mediate within youth culture can only be fully understood in relation to club cultural ideologies. For the positioning of various media outlets – prime-time television chart shows versus late-night narrowcasts, BBC versus pirate radio, the music press versus the tabloids, flyers versus fanzines – as well as discourses about ‘hipness’, ‘selling out’, ‘moral panic’ and ‘banning’ are essential to the ways young people receive these media and, consequently, to the ways in which media shape subcultures.

Mass Media: ‘Selling Out’ and ‘Moral Panic’

Scholars all too often make generalizations about the media based on an analysis of television alone. In the mid-nineties, however, mass media are in decline and the dominance of television – or at least broadcasting – is in question. We are in an age of proliferating media, of global narrowcasting and computer networks where anyone on-line is ‘nearby’. To make sense of the complexity of contemporary communications, it is necessary to divide the media into at least three layers. From the point of view of clubbers and ravers, in particular, micro, niche and mass media have markedly different cultural connotations. Moreover, their diverse audience sizes and compositions and their distinct processes of circulation have different consequences for club cultures. With mass media, for instance, affirmative coverage of the culture is the kiss of death, while disapproving coverage can breathe longevity into what would have been the most ephemeral of fads. In this section, I examine these dynamics of ‘selling out’ and ‘moral panic’ in relation to three national media: prime-time television, national public service radio and mass circulation tabloid newspapers.

Although the situation is changing, most British homes still receive only four television channels; cable and satellite TV’s audience share hovers just under eight per cent (in 1995): MTV Europe has so few British viewers that it generally refuses to release figures, saying only that the number of homes connected is three and a half million (and sixty-one million for all of Europe). Of the terrestrial stations, the public service BBC1 and commercial ITV account for almost seventy per cent of all television viewed. Television in Britain is therefore, for the time being, a mass medium in the old sense of word: there is relatively little regional or local programming and niche targeting is a recent entreprise which tends to operate well only outside prime-time. As a result, the only regular prime-time music show occupies a key position within the symbology of the underground.

Having been on the air for over twenty-five years, Top of the Pops has close to universal brand recognition; it is seen as the unrivalled nemesis of the underground and the main gateway to mass culture. This half-hour programme combines ‘live vocal’ performances attended by a free-standing studio audience with video clips – both of which are introduced according to their current position in that week’s top forty. The show is considered so domestic, familial and accessible that the ultimate put-down is to say a club event was ‘more Top of the Pops on E than a warehouse rave’ (i-D June 1990). Moreover, it is assumed that ‘for dance music to stay vital, to mean more than the media crap we’re fed from all angles, it has to keep Top of the Pops running scared’ (Mixmag December 1991).

This disdain for Top of the Pops is tied up with a measure of contempt for the singles sales chart. Clubbers have a general antipathy to what they call ‘chartpop’ (or occasionally ‘chartpap’), which does not include everything in the top forty but rather the ‘teenybop’ material identified with girls between eight and fourteen (who are most likely to buy seven-inch singles).* However, when it comes to dance music, clubbers and ravers seem concerned less with actual sales figures than with concomitant media exposure – the ancillary effects of chart placement on television programming, radio playlists and magazine editorial policies. This is perhaps best demonstrated by the fact that clubbers and ravers tend to have deep admiration for tracks that got into the top ten without any radio or video play – simply on the strength of being heard in clubs, covered in the specialist press and bought on twelve-inch by clubbers alone.

Top of the Pops, rather than the singles chart per se, is seen as a key point of so-called ‘selling out’. For instance, a member of a techno dance act (called LFO) with a single in the charts warns, ‘don’t expect to see us on Top of the Pops. We might let them show the video, but we [won’t] have people pointing at us, regarding us as sell-outs. LFO is purely underground stuff… We hate all those false and fake people in the charts. We only like the hard stuff (NME 28 July 1990). If one were to take this discourse about ‘selling out’ at face value, one might see it as anti-commerce or resistant.

Dick Hebdige theorizes ‘selling out’ as a process of ‘incorporation’ into the hegemony. He describes this recuperative ‘commercialization’ as an aesthetic metamorphosis, an ideological rather than a material process whereby previously subversive subcultural signs (such as music and clothing) are ‘converted’ or ‘translated’ into mass-produced commodities (Hebdige 1979: 97). But as the popular rhetoric of ‘selling out’ assumes that records with low sales aren’t ‘commercial’ (even though they are obviously products of commerce) and validates the proliferating distinctions of consumer capitalism, this fusion of populist and Marxist discourses is wistful.

Within club undergrounds, it seems to me that ‘to sell’ means ‘to betray’ and ‘selling out’ refers to the process by which artists or songs sell beyond their initial market which, in turn, loses its sense of possession, exclusive ownership and familiar belonging. In other words, ‘selling out’ means selling to outsiders, which in the case of Top of the Pops means those younger and older than the club-going sixteen-to-twenty-four-year olds who do not form the bulk of the programme’s audience, partly because they watch less television than any other age-group. (The ratings of Top of the Pops are generally highest amongst twelve-to-fifteen-year-olds, followed by those between twenty-five and thirty-four, then the thirty-five to forty-four age-group.)

Despite several academic arguments about the opposition of youth subcultures and television culture (implicit in the Birmingham work, explicitly argued by Attallah 1986 and Frith 1988a). British youth subcultures aren’t ‘anti-television’ as much as they are against a few key segments of TV that expose youth subcultural materials to everybody else. The general accessibility of broadcasting, in the strict sense of the word, is at odds with the esotericism and exclusivity of club and rave cultures; it too widely distributes the raw material of youth’s subcultural capitals. Other music-oriented television programmes which tie into club culture like MTV Europe or ITV’s Chart Show have not accrued the connotations of Top of the Pops. First, these programmes are sufficiently narrow-cast to escape negative symbolization as the overground. Second, they have high video content – a form which is somehow seen to maintain the autonomy of music culture and has credibility amongst clubbers.

The techno artist quoted above differentiates between appearing on Top of the Pops in person (which amounts to ‘selling out’) and appearing in video (which is considered a legitimate promotion). This is a common distinction of the underground.* Frith argues that ‘the rise of pop video has been dependent on and accelerated the decline of the ideology of youth-as-opposition’ (Frith 1988a: 213). But many dance acts seem to think that videos help them resist ‘selling out’. A couple of factors might contribute to this attitude. First, videos allow the band to present themselves (with the help of the marketing and promotions departments of their record company) in a controlled manner closer to their own terms. Videos enable them to avoid being tainted by the ‘naff context of Top of the Pops. The artists protect their authentic aura by refusing to make a physical appearance (see above, pp. 27, 80–4). Second, the practice of lip-synching and acting out songs which have no ‘live’ existence undermines the creative credibility of these artists. With few lyrics and few performers per se, much contemporary dance music (particularly house and techno) is still in the process of developing an effective style of ‘live’ presentation. As discussed earlier in the book, much of this elaboration does not centre on the performer as much as on technology (like bringing the studio and new visual forms to the audience) so it tends not to make the most gripping television.

Videos are considered by many to be an appropriate visual accompaniment to a music which is quintessentially recorded. This is particularly the case with dance videos that use animated or computer-generated graphics and abstract visuals which forego depicting the artist. It is now often forgotten that the music video had its debut in discos in the seventies and is still a feature of many clubs. In fact, in 1977, ninety per cent of the video cassette sales were to discos (Music Week 24 September 1977).

Dance acts must nevertheless occasionally negotiate ‘live’ Top of the Pops appearances. For, as one television promotions manager put it, ‘underground or not, major labels encourage their dance acts to appear because Top of the Pops shows hardly any videos, unless you’re U2 or a breaker and then you only get twenty seconds’ (Loraine McDonald, EMI: Interview, 2 September 1992). Two basic strategies for maintaining an underground sensibility and immunizing oneself against the domesticity of Top of the Pops are disguise and parody; dance acts frequently hide their faces with sunglasses, hoods and hats and / or go ‘over the top’ in their performance. Nothing is less ‘cool’ than taking Top of the Pops seriously.

The other TV programme crucial to youthful conceptions of the national club scene during the 1988–92 period was The Hitman and Her. When house music became too popular for its early aficionados, it was deplored as being ‘Hitman and Her fodder’ (letter to Herb Garden April 1992). Though similarly denigrated, this late-night low-budget show was caught in a different cultural logic from Top of the Pops. The show was shot on location in dance clubs, rather than television studios, featured a local club crowd rather than a studio audience and revolved around a DJ-presenter (the Hitman) and his assistant (Her). The closest American equivalent to The Hitman and Her might have been a programme like Club MTV which was shot at the Palladium in New York City. But the MTV show was hosted by a black British woman with a young ‘hip’ image (‘Downtown Julie Brown’), the dancers were vetted and video clips were used to relieve the viewer from the monotony and embarrassment of watching non-professionals dance.

The Hitman and Her offended underground sensibilities in at least three ways. First, the show’s reception was entangled with the cultural positioning of its DJ-presenter, Pete Waterman, who was also a producer with Stock and Aitken of many chart hits. After many consecutive pop hits, but particularly after the success of Kylie Minogue, a soap opera actress-cum-singer with a large female teenybop audience, Stock/Aitken/Waterman came to be considered as manufacturers of sentimental ‘chartpap’ to the extent that their music was frequently cited as evidence of the cultural bankruptcy of the major record companies even though they put out much of their work on Waterman’s independent label, PWL. Stock/Aitken/Waterman signified the low end of popular music even more than Top of the Pops.

Worse still, as a DJ, Waterman was seen as someone who preferred to ‘fill a club to the rafters with 2,000 of the biggest wallies than have it half empty with the coolest trendies’ (Clubland March 1992). This was the second reason for clubber difficulties with The Hitman and Her – the crowds in these televised clubs were not remotely underground. They were as close to the imagined ‘Sharons and Tracys’ as television could provide. The following statement amends the stereotype to include the men depicted on screen and damns the show with faint praise:

Despite coming from the No Jeans, No trainers, Soul in a Basket optional end of clubland, there is something perversely enticing about this programme… Pleasure can be gleaned from the sight of 2,000 Herberts and Tracys dancing around their beer and handbags at La Discothèque… The appeal of The Hitman and Her lies in its honest approach, its admittance of the ‘so bad, it’s good’ theory. (Soul Underground April 1989)

Even with a new presenter and a different crowd, The Hitman and Her would not win subcultural capital, not that it didn’t try. In 1992, Pete Waterman set up a techno label called PWL Continental featuring acts like 2 Unlimited, Capella and Opus III, and the television programme was transformed into a ‘mental rave night’ called Not the Hitman and Her (DJ April 1992). However, the act of putting bright lights on the crowd as opposed to the dance acts – the process of illuminating a culture that is supposed to take place in the dark – usually destroys the atmosphere that is the linchpin of club authenticity.

Documentarists of club and rave culture repeatedly use techniques like slow motion, rapid and rhythmic editing, extremely high and low camera angles, continuously moving cameras, computer-generated blurs and high grain celluloid stocks in their attempt to capture the frissons of a ‘hip’ night out. (See, for example, the following hour-long documentaries: Club Culture 1988, Ibiza: A Short Film About Chilling 1990 and Madchester 1990.) Borrowing from promotional video rather than documentary traditions, these televisual techniques protect the dancers from the harshest of the camera’s demystifying glares. They create a new televisual atmosphere rather than trying to capture a club one.

Research repeatedly finds that young people have more respect for adult-orientated programming than for shows made specifically for their age-group. The ‘so bad, it’s good’ index of appreciation is often the best that non-video youth programming can hope for. Channel 4’s The Word and BBC2’s DEF II programmes often fall into this category. According to some market researchers, ‘TV programmes made for a young audience are not always the most effective way for youth advertisers to reach their market … Fashion advertisers are better off avoiding The Word if they want to target trend setters who think the show is naff’ (Music Week 15 April 1993).

As a medium of image, print and sound which fills more leisure hours than any other form of communication, television is in a unique position to violate the esotericism and semi-privacies of club culture. Nevertheless, clubber and raver discourses about television programmes are intricate and full of discrepancies. They relate to the audience at home because undiscriminating exposure to outsiders is a betrayal. They concern the people depicted who can become objects of ridicule rather than points of identification, seeming incarnations of an ideological other. Underground discourses also involve issues of format and aesthetics in so far as music video and its stylistic practices are valued as means by which music culture can be televised but somehow preserve its rhetorical autonomy and authenticity.

Though these are the prevailing ideologies of club culture, they are not all determining nor without loopholes. For example, a Top of the Pops appearance is often seen by the dance act’s original fans as an affirmation of their taste as well as something to be viewed with suspicions of ‘selling out’. Ironically, nothing proves the originality and inventiveness of subcultural music and style more than its eventual ‘mainstreaming’. Similarly, subcultures that never go beyond their initial base market are ultimately considered failures. Moreover, programmes like Top of the Pops are important for the recruitment of fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds to youth subcultures as its eclectic playlists frequently offer glimpses of other-worldly cult music cultures.

The betrayals of broadcasting and the aesthetics of atmosphere are but two cultural logics of club undergrounds. Negative coverage in the form of either well-publicized omissions from programmes like Top of the Pops (sometimes characterized as censorship) or television news features on club and rave culture as a serious social problem (often framed as ‘moral panic’) are also important to the relationship between media and youth subcultures. Even though they are relevant to television, I will discuss these issues in relation to radio and tabloids where they constitute a more commanding dynamic.

Youth resent approving mass mediation of their culture but relish the attention conferred by media condemnation. How else might one turn difference into defiance, lifestyle into social upheaval, leisure into revolt? ‘Moral panics’ can be seen as a culmination and fulfilment of youth cultural agendas in so far as negative newspaper and broadcast news coverage baptize transgression. Whether the underground espouses an overt politics or not, it is set on being culturally radical. In Britain, the best guarantee of radicalism is rejection by one or both of the disparate institutions seen to represent the cultural status quo: the tempered, state-sponsored BBC (particularly pop music Radio One) and the sensational, sales-dependent tabloids (particularly the Tory-supporting Sun).

Although their audience share has declined markedly due to increased competition from newly licensed local stations, during the period in which I did the bulk of my research, Radio One was listened to by over thirty per cent of the British population every week – and notably more women than men. Unlike Top of the Pops (and contrary to common perception), the radio station did not limit its output to the top forty, but played an average of 1100 different titles a week, including dance catalogue, particularly from the more melodic end of the genre. Although it had specialist dance shows (like Pete Tong’s Friday night ‘Essential Selection’), the dance-oriented press tended to alternate between complaining that the station gave short shrift to dance music, and admiring genres like acid house and techno for not being radio musics. Either way, Radio One represented the accessible and safe mainstream.

Being ‘banned’ from Radio One was therefore a desirable prospect. It acted as expert testimony to the music’s violation of national sensibilities and as circumstantial evidence of its transgression. Being banned was consequently the most reliable way to gain what is in theory a contradiction in terms, but in practice a relatively common occurrence – namely an underground smash hit. The Beatles’ ‘A Day in the Life’ (1967), Donna Summer’s ‘Love to Love You Baby’ (1976), The Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save The Queen’ (1977), Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s ‘Relax’ (1984), George Michael’s ‘I Want Your Sex’ (1987) and The Shamen’s ‘Ebeneezer Goode’ (1992) were all banned because of their references to sex, drugs or politics. All of them either became hit singles or were hit singles which went on to spearhead hit albums. In the case of tracks featuring the word ‘acid’, several climbed from the bottom forty to the top forty as a result of rumours alone.

For example, in October 1988, the first explicitly acid track to enter the top twenty, D-Mob’s ‘We call it Acieeed’, caused some commotion. Radio One denied allegations, which emerged from the D-Mob’s record company, of having banned the record, explaining that the single was not on the playlist because ‘it wasn’t right for the mood of some programmes such as the breakfast show’. However, as the Radio One playlist functioned only at peak times, the single had received fourteen plays from individual producers outside the playlist system, more times, in fact, than the Whitney Houston track that was number one that week. In other words, Radio One insisted that they had imposed no ban on acid house in the strict sense of the word, that is, they were not censoring acid house. However, the record company kept suggesting that the music was ‘banned’ in the conveniently loose sense of the word, namely that acid house was not playlisted. The subcultural consumer press favoured the more sensational record company line – it made better copy and kept things friendly with a main advertiser – and few clubbers took note of the story’s sources or distinguished between the two kinds of ‘banning’.

The BBC is conscious of the curiosity generated by anything alleged to be censored. As the executive producer of the station at the time explained, ‘Radio One, as part of the BBC, is seen as the establishment … and anything considered anti-establishment has a head start as far as teenagers are concerned’ (Stuart Grundy, Interview: 26 August 1992). As a result, the BBC tries to keep their gatekeeping low profile and if that fails it attempts to play down the offending issues. With reference to the ‘acieeed’ lyrics of the D-Mob single, a BBC spokesman stated that the radio service understood the song to be anti-drugs: ‘it expresses the ideal sentiments for our forthcoming Drug Alert campaign’ (NME 29 October 1988). Meanwhile the then Radio One DJ Simon Bates gave interviews asserting that ‘Acid is all about bass-line in the music and nothing to do with drugs’ (Daily Mirror quoted by NME 12 November 1988).

Back in January 1988, however, London Records (a subsidiary of Polygram) had successfully launched acid house as a genre on the coat-tails of its drug-oriented potential for scandal. The sleeve-notes to The House Sound of Chicago Volume III: Acid Tracks described the new music as ‘drug induced’, ‘psychedelic’, ‘sky high’ and ‘ecstatic’ and even concluded with a prediction of ‘moral panic’: ‘The sound of acid tracking will undoubtedly become one of the most controversial sounds of 1988, provoking a split between those who adhere to its underground creed and those who decry the glamorization of drug culture.’ In retrospect, this seems remarkably prescient, but the statement is best understood as hopeful. ‘Moral panics’ are one of the few marketing strategies open to relatively anonymous instrumental dance music.

While the BBC conducts its ‘bans’, the logic of ‘moral panic’ operates most conspicuously within the purview of the tabloids. Britons have a choice of eleven national daily newspapers which range between ‘quality’ broadsheets and ‘popular’ tabloids. Unlike papers like National Enquirer or USA Today, the British tabloids are read by over half the British population every day. They cover political issues in dramatic, personal and often sexual terms (hence the biggest selling Sunday paper, News of the World, is nicknamed News of the Screws). They take a regular interest in youth culture which they tend to treat as either a moral outrage or a sensational entertainment, often both. In fact, in line with their interest in gaining and maintaining young readers, the Sun’s favourite ‘moral panics’ would seem to be of the ‘sex, drugs and rock’n’roll’ variety – stories about other people having far too much fun – which allow their readers to vicariously enjoy the transgression one moment, and then to be shocked and offended the next. As Mark Pursehouse writes, one of the key pleasures in reading the Sun is the process of making a judgement about which parts of a story are true, which parts invented (Pursehouse 1991: 108). Despite questions of credibility, the tabloids have a swift domino effect: their ‘shock! horror!’ headlines frequently make the news themselves, are relayed by television, radio and the quality newspapers and generate much word-of-mouth, so that one often knows what’s going on in the tabloids without having read them.

Mods, rockers, hippies, punks and New Romantics have all had their tabloid front pages, so there is always the anticipation – the mixed dread and hope – that a youthful scene will be the subject of media outrage. Disapproving tabloid stories legitimize and authenticate youth cultures. In fact, without tabloid intervention, it is hard to imagine a British youth movement. For, in turning youth into news, the tabloids both frame subcultures as major events and also disseminate them. A tabloid front page, however distorted, is frequently a self-fulfilling prophecy; it can turn the most ephemeral fad into a lasting development.

Following London Records’ sleeve-notes, the subcultural press repeatedly predicted that a ‘moral panic’ about acid house was ‘inevitable’. In February 1988, a good six months before a daily paper ran a story and a few weeks after the compilation’s release, the three main music weeklies ran stories about a new genre called ‘acid house’ that was liable to cause ‘moral panic.’ As one of them put it: ‘I wonder how long it will be before our moral guardians start claiming that promoting the music is helping to promote drug-taking among the young?’ (Record Mirror 20 February 1988).

Some months later, innuendo about drug use in British clubs started to appear in the style and music press, but it was left to two music weeklies experiencing flagging sales (and with little feeling of responsibility to this particular club scene) to expose domestic drug-taking. In July 1988, New Musical Express (NME) ran several stories under the Timothy Leary slogan ‘Tune in, Turn on, Drop Out’ which exposed and investigated Ecstasy use in British clubs. Although they admitted that it was ‘hardly a matter for public broadcast’, they explained the appeal of the drug (it gave one the energy to dance all night and reduced inhibitions). They also offered proof of its prevalence (the names of London’s house clubs signalled the chemical nature of their attraction, while the packed dancefloors and deserted bars suggested that alcohol was not the preferred substance) and they listed the possible negative effects like nausea and recurring nightmares, emphasizing however that the worst effect was ‘making a complete and utter embarrassment of yourself by babbling E-talk and intimate confessions to whoever happens to be in earshot’ (NME 16 July 1988). Melody Maker followed with stories like ‘Ecstasy: a Consumer’s Guide’ which rated batches of MDMA. The legendary ‘yellow capsules’, they said, induced ‘feelings of having being ripped off and a buzz akin to trapping your toe in the door’, while the ‘New York tablets’ were the ‘most … reliable Ecstasy … the lasting sensation being one of unbruisability and general bliss’ (Melody Maker 20 August 1988).

Plate 5 Front-page coverage of the rave scene, June 1989. The caption read: ‘Night of Ecstasy … thrill-seeking youngsters in a dance frenzy at the secret party attended by more than 11,000’ (Reproduced by kind permission of the Sun)

By the end of August, many music and style magazines were wondering why the tabloids were ignoring the issue. Ecstasy, some complained, had ‘received little of the gutter press scare treatment afforded Crack yet the latter drug has yet to make any real inroads into British drug culture’ (NME 13 August 1988). Others seemed amazed that the acid house scene was ‘in many ways … still an underground movement’ but, confident of eventual ‘moral panic’, went so far as to project possible headlines:

It’s not hard to imagine the angle the tabloid press will choose if they ‘report’ on the acid house scene. Its supposedly symbiotic relationship with psychedelic drugs will make banner headlines of shock-horror proportions, along the lines of ‘London Gripped by Ecstasy!’, ‘Drug Crazed New Hippies in Street Riot’ or ‘Yuppies On Acid!’ The clubs will be portrayed as drug dens, the music will be ‘mind-numbing’ and the clubbers ‘hooligans’. It could be the ideal Silly Season story once Fergie’s little Princess has left the front page. (Time Out 17–24 August 1988)

When the ‘inevitable’ ‘moral panic’ ensued, the subcultural press were ready. They tracked the tabloids’ every move, reproduced whole front pages, re-printed and analysed their copy and decried the misrepresentation of acid house by what they variously called ‘moral panic’, ‘media hysteria’, a ‘gutter press hate campaign’ and a ‘moral crusade’. However much they condemned the tabloids, clubbers and club writers were fascinated by their representation and gloried in the sensational excess. As one journalist admitted, ‘The irony is that whilst [the Sun] runs acid stories, I buy the paper everyday, just to see what they dream up next’ (Soul Underground July 1989).

Even well after the waves of tabloid coverage, dance magazines and fanzines compiled top ten charts of ‘ridiculous platitudes’ used by the popular press – ‘Killer Cult’, ‘In the grip of E’, ‘Rave to the Grave’ (Herb Garden June 1992). Others ran spoof scandals about millions of kids ‘hooked on a mind bending drug called A’ (for alcohol) or stories about the designer drug ‘T’ which was ‘openly on sale in supermarkets and supplied in a small perforated bag’ (Herb Garden June 1992; Touch February 1992). Impressed but not surprised, the club press had their explanations. As i-D, a magazine whose reader-profile brags that it is, according to the Economist, ‘painfully hip’, wrote:

Every sub-culture breeds its own moral panic, every moral panic is stereotyped by its own devil drug. Think of all those headlines from the past which have screamed themselves hoarse: mods on speed, freaks dropping LSD, punks sniffing glue, blacks smoking dope, even cocaine-crazed yuppies. Gay bikers on acid just about sums it up. (i-D June 1990)

In 1991, however, when the negative stories had lost their news value, the tabloids started publishing positive articles with headlines like ‘Bop to Burn: Raving is the Perfect Way to Lose Weight’, ‘High on Life’ and ‘Raves are all the Rage’. Needless to say, clubbers and their niche press were outraged. How could the tabloids about-face and ignore the abundant use of drugs? How did they think ravers stay up till 6 a.m., if it weren’t for the numerous amphetamines inside them? The music press attacked these affirmative tabloid stories with unprecedented virulence. For example, Touch magazine wrote:

‘10,000 DRUG CRAZED YOUTHS’ This was the headline carried by the Sun newspaper during the summer of 1988. It was part of an uncompromising effort to bring disrepute and destruction upon the rave scene that was growing at a rapid rate across the country … Now three years after that headline was printed, the Sun has launched ‘Answers’ – its so called comprehensive guide to weekend raving … What audacity! How dare they? On approaching the Sun about their change in attitude we were informed by some clueless dimwit that the rave scene is now, in their opinion, a respectable, clean and drug-free zone. Anyone who has been to the major clubs recently knows that drugs are still very much a part of the club rave culture. We’re not saying this is a good thing, but it does prove that the Sun knows absolutely fuck all about what’s happening on the Rave scene, just as they knew fuck all in 1988 and 1989. The truth is that the Sun is run and staffed by a bunch of hypocritical, no good, Tory, band-wagon jumping wankers. (Touch December 1991)

Although negative reporting is disparaged, it is subject to anticipation, even aspiration. Positive tabloid coverage, on the other hand, is the subcultural kiss of death. In 1988, the Sun briefly celebrated acid house, advising their readers to wear T-shirts emblazoned with Smiley faces, the music’s coat of arms, in order to ‘dazzle your mates with the latest trendy club wear’, before they began running hostile exposés. Had the tabloid continued with this happy endorsement of acid house, it is likely the scene would have been aborted and a movement would not have ensued. Similarly, rave culture would probably have lost its force with this second wave of positive reports had it not been followed by further disapproving coverage (about ravers converging on free festivals with ‘travellers’, namely, nomadic ‘hippies’ and ‘crusties’ who travel the countryside in convoys of ‘vehicles’).

Cultural studies and sociologies of ‘moral panic’ tend to position youth cultures as innocent victims of negative stigmatization. But mass media ‘misunderstanding’ is often an objective of certain subcultural industries, rather than an accident of youth’s cultural pursuits. ‘Moral panic’ can therefore be seen as a form of hype orchestrated by culture industries that target the youth market. The music press seemed to understand the acid house phenomenon in this way, arguing that forbidden fruit is most desirable and that prohibition never works. The hysterical reports of the popular press, they argued, amounted to a ‘priceless PR campaign’ (Q January 1989). Perhaps the first publicist to court moral outrage intentionally was Andrew Loog Oldman who, back the mid-1960s, promoted the Rolling Stones as dirty, irascible, rebellious and threatening (cf. Norman 1993). Rather than some fundamental innovation, Malcolm McLaren’s management of the image of the Sex Pistols in the 1970s followed an already well-trodden promotional path. In the 1980s and 1990s, acts as disparate as Madonna, Ice-T and Oasis have played with these marketing strategies, for ‘moral panic’ fosters widespread exposure at the same time as mitigating accusations of ‘selling out’. (Hence, the usefulness of ‘Parental Advisory’ stickers in marketing certain kinds of acts in the US.)

‘Moral panic’ is a metaphor which depicts a complex society as a single person who experiences sudden groundless fear about its virtue. Although the term serves the purposes of the record industry and the music press well by inflating the threat posed by subcultures, as an academic concept, its anthropomorphism and totalization mystify more than they reveal. It fails to acknowledge competing media, let alone their reception by diverse audiences. And, its concept of morals overlooks the youthful ethics of abandon.

Popular music is in perpetual search of significance. Associations with sex, death and drugs imbue it with a ‘real life’ gravity that moves it beyond lightweight entertainment into the realm of, at the very least, serious hedonism. Acid house came to be hailed as a movement bigger than punk and akin to the hippie revolution precisely because its drug connections made it newsworthy beyond the confines of youth culture. While subcultural studies have tended to argue that youth subcultures are subversive until the very moment they are represented by the mass media (Hebdige 1979 and 1987), here it is argued that these kinds of taste cultures (not to be confused with activist organizations) become politically relevant only when they are framed as such. In other words, derogatory media coverage is not the verdict but the essence of their resistance.

So far the discussion has focused on mass media such as prime-time television, national radio and tabloid newspapers whose audiences, aesthetics and agendas are generally contrary to underground ideology. But, what about those micro and niche media which are more directly involved in the congregation of dance crowds and the formation of subcultures? What kind of reputation do they have amongst clubbers and ravers? How do they circulate and control the flow of the crowd?

Micro-Media: Flyers, Listings, Fanzines, Pirates

Flyers, fanzines, flyposters, listings, telephone information lines, pirate radio, e-mailing lists and internet archive sites may not at first seem to have much in common. An array of media, from the most rudimentary of print forms to the latest in digital interactive technologies, are the low circulating, narrowly targeted micro-media which have the most credibility amongst clubbers and are most instrumental to their congregating on a nightly basis. Club crowds are not organic formations which respond mysteriously to some collective unconscious, but people grouped together by intricate networks of communications. Clubbers elect to come together by making decisions based on the information they have at hand at the same time as they are actively assembled by club organizers.

The media venerated for epitomizing the authenticity of dance subcultures are first and foremost word-of-mouth, word-on-the-street and fanzines. Although these media are romanticized as pure and autonomous, they are generally tainted by and contingent upon other media and other business. While they are assumed to be in the vanguard, they are just as likely to be belated and behind. Though these media are said to be closest to subcultures, various social and economic factors limit and complicate their intimate relations.

Word-of-mouth is considered the consummate medium of the underground. But conversations between friends about clubs often involve flyers seen, radio heard and features read. Rather than an unadulterated grassroots medium, word-of-mouth is often extended by or is an extension of other communications’ media. For this reason, club organizers, like other marketers and advertisers, actively seek to generate word-of-mouth with their promotions. Likewise, romantic notions of the ‘street’ forget that it is a space of advertising and communication, subject to market research and given ratings called ‘OTS’ or ‘opportunities to see’. The ‘OTS’ rating considers the details of people who pass particular poster and billboard sites in cars or on foot, adjusting figures to take into account distractions such as rival sites or poor visibility. Although they do not survey illegal communications like flyposting or spray painting, we can infer a similar demographic bias of young, male and upmarket viewers. This is one reason why record companies allot marketing pounds to what they call ‘street marketing’ and why flyposting and spray-painting are effective means for rave organizations to gain a higher profile and draw a crowd. Word-of-mouth and word-on-the-street are rarely as pure and autonomous as clubbers (and academics) would like to believe.

More than any other medium, perhaps, fanzines have been celebrated as grassroots – as the active voice of the consumer and as the quintessence of subcultural communications. While the former is undoubtedly true, the latter is open to question. Rave fanzines give vent to unruly voices, local slang, scatological juvenilia, moaning, ranting and swearing. First person narratives are common, particularly ones about drug experiences which recount stories of brilliant or nightmarish times on Ecstasy, tales of having one’s ‘gear’ stolen by bouncers who then sell it back to you in the club, anecdotes about experiencing ‘aggro’ from ‘charlie casuals’ and lager louts’ (namely, aggravation from abusers of cocaine and beer).

Having small print runs and little money to lose, the fanzines often flout libel and copyright laws, if only in hope of a bit of publicity. Some make allegations about the sexual exploits of ‘high profile, coke snorting’ record company bosses (Gear 2 1991). Others ask outright: ‘Do you know a cause worth fighting or more importantly any chance of some free publicity? Write and let us know. We pay five pounds’ (Herb Garden April 1992).

Fanzines are the only place to find writing about clubbing from an explicitly female (though not always feminist) point of view. Several were edited by women (for example, Duck Call and Gear), while even the laddish Boy’s Own has the occasional ‘Girl’s Own Nightmare’ feature which discusses such problems as ‘death by sisterhood on eight tabs’, surviving the loo queue and the handbag problem. Similarly, Herb Garden ran a spoof of a woman’s magazine quiz which determined whether you were a ‘Sad Susan’ who doesn’t know a thing about dance culture, a ‘Techno Tracy’ who raves all the time but indiscriminately, or a ‘Vicky Volante’ (the name of the author of the mock quiz) who has the right attitude and knows how to have fun with style. Significantly, these fanzine articles by female writers are careful to distance themselves from dancing around handbags, Sharon and Tracy (techno or otherwise) (cf. chapter 3).

While the rave fanzines are certainly outlets for clubber debate, they are not, as is often assumed, necessarily emergent. Most of the rave fanzines appeared in the aftermath of the tabloid ‘moral panic’ and did little to contribute to the early evolution of acid house. NME tried to explain the absence of fanzines by the fact that the music did not revolve around artists: ‘That there isn’t already a massive acid house fanzine scene is partly down to the anonymity of the idiom. It’s rarely performed live, which is why the DJs who play the sounds in clubs have a higher profile than the musicians who make them’ (NME July 16 1988). But the early fanzines could have focused on DJs as did the later ones which were full of hagiographic articles with titles like ‘Seventeen things you never knew about Danny Rampling’ (Herb Garden April 1992).

All but one fanzine appeared long after British acid house had been converted into a ‘scene’ by the subcultural consumer press because before the niche media baptism, the culture consisted of little more than a dozen tracks, a few clubs and DJs. Moreover, even when the numbers of people involved swelled through the summer of 1988, it was not long before the tabloids were on the case. Professional media are generally faster off the mark, working to monthly, weekly and daily deadlines rather than the slow productions and erratic schedules of amateur media. Even after their proliferation, then, the fanzines tended to write about events that happened months prior to their publication and were well behind the consumer press.

Free from the constraints of maintaining readerships, fanzines don’t have to worry about being identified with a scene that has become passé. Much fanzine copy therefore wallows in nostalgia. Their writers reminisce about the legendary raves and hanker after the initial ‘vibe’. Conscious of lying in the wake of a historic youth movement, even when they try to avoid sentimental longing, it often prevails. For example:

My purpose is not to describe the pre-Fall idyll, some sonic paradise which we should wander as do unreconstructed hippies to Glastonbury [but] rather to lament the way clubland has so quickly become self-conscious and unspecial. Acid house was not the be-all and end-all, but it was a beginning, and something that was stamped out before it was allowed to develop. (Boy’s Own spring 1990)

To have attended any event which was given notoriety by the tabloids has its own subcultural capital. Certainly many wished they had been there – contributing to the news and taking part in youth cultural history. One of the bigger club organizations, which obtained more tabloid front pages than any other, was banking on such nostalgia when it released videos of its ‘Sunrise’ and ‘Back to the Future’ parties. Its advertisement asked, ‘Do you remember the raves of 88 and 89? Capture your cherished memories on VHS video cassettes, from the days we travelled the orbital and no town, field or warehouse was safe’ (Clubland December 1991/January 1992).

Word-of-mouth and fanzines are likely to be residual as much as emergent means of communication. The idea that subcultural scenes are seeded with micro-media, cultivated by niche media and harvested by mass media describes the exception as much as the rule. There is no natural order to cultural development. In competitive economies where sundry media work simultaneously, where global industries are local businesses and ‘all that is solid melts into air’ (cf. Berman 1983), organic metaphors about ‘grassroots’ and ‘growth’ eclipse as much as they explain. They are too unitary to make sense of the complex teleologies of contemporary popular culture. Culture emerges from above and below, from within and without media, from under- and overground.

Flyers are considered by many club organizers as the most effective means of building a crowd in so far as they are a relatively inexpensive way to target fine audience segments. Their distribution is conducted in three ways: they are mailed directly to clubbers (often members) in the form of invitations, handed to people in the street ‘who look like they belong’ or distributed to pubs, clothing and record shops in order that they might be picked up by the ‘right crowd’. While the first method uses the means of the private party, the last two trace young people’s routes through the city, exhibiting an understanding of what Michel de Certeau would call their ‘practices of space’ (de Certeau 1984). Club promoters talk about how the dissemination of flyers is a deceptively tricky business: one must be wary of printing too many and finding them littering the streets; of depositing them in unsuitable places and procuring a queue full of ‘wallies’. The dispersal of flyers influences the assembly of dance crowds; the flow of one affects the circulation of the other.

In her book Design After Dark: the Story of Dancefloor Style, Cynthia Rose celebrates flyers as ‘semiotic guerilla warfare’, likening the form to the old political handbill as well as new art forms which play with mass reproduction processes. But while flyers have clear aesthetic significance, they are more accurately seen as direct advertising rather than cultural combat. ‘Direct marketing’ is the subject of more advertising investment than either magazines or radio, but because it targets tightly, it often feels more intimate and less ‘commercial’ (Marketing 13 August 1992). Moreover, rather than contesting the status quo, flyers mainly suggest that the club whose name they bear satisfies questions like the following: ‘Where can you find the wildest, craziest, maddest, most hedonistic, HARD CORE, dance experience that takes place every Friday and Saturday night?’ (printed on Uproar flyer 1990).

Mailing lists are compiled in a variety of ways. Sometimes, advertisements in fanzines and the subcultural consumer press invite people to send ten pounds to become a member, or one can pay for membership at the door. At other times, the addresses of regulars are requested by the club organizer or, in the case of a club called Rage (held at Heaven in London), people were chosen from amongst the crowd to have their picture taken, then were issued with a photo I.D. and placed on the mailing list.

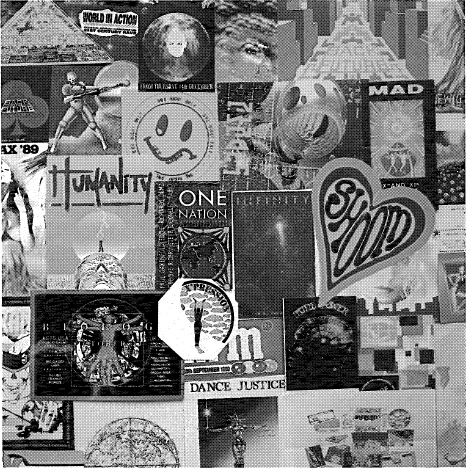

Plate 6 A selection of flyers from 1988–89

(Photograph: David Swindells)

Key recipients of flyers are local listings magazines which relay their information (along with that of accompanying press releases) to preview or review clubs for their readers. Listings magazines contain at least three gradations of exposure: the relative obscurity of the listings themselves, the discreet disclosure of a column-mention or the open exhibition of a feature in the front pages. The listings are written in a kind of clubber jargon that is often incomprehensible to those who are not already familiar with clubbing. (For example, some American students at the London School of Economics for a term told me that after scouring Time Out’s club listings, they were still bewildered about where they ought to go.) When a club is singled out for recommendation or comment in the columns which precede the listings, overviews are offered and terms are occasionally defined. When the magazine runs a feature – usually on a new scene or ‘vibe’ – labels are translated and codes revealed; the culture is exposed and explained to non-clubbing outsiders.

Published listings need to be negotiated as carefully as flyer distribution. They can stimulate or stifle interest, under- or overexpose. While a crowd needs to be assembled, too much or the wrong kind of coverage can close down a club in a matter of weeks. Just enough and the right kind of publicity, on the other hand, can reserve a place in the annals of club cultural folklore. Shoom, the club retrospectively hailed as the origin of acid house culture, offers a telling case of the cultural logics involved.

The first entry for this Saturday-night club in the London listings weekly, Time Out, read as follows:

NEW! The Shoom Club, Midnight – 5 a.m. If you’re lucky enough to get one of their invites then you’ll know the location of this underground House party in E1 which was packed and jumping at their Valentine rave and now goes weekly. DJ Danny Rampling and guest DJs the Cold Cut Crew mix the House variations and rap-dance for a very lively crowd of trendies with great decor on the walls. It’s fast becoming a legend so become a member before it’s too big for its venue. (Time Out 24 February–2 March 1988)

The implied thrills of being part of an elect and taking part in the ‘hip’ and ‘happening’ are common to club listings; therefore it is two other themes which set this blurb apart from the rest. First, although the club had yet to operate weekly, the listing predicts the club’s mythic status: it is ‘fast becoming a legend’. Like the sleeve-notes to London Records’ Acid Tracks compilation which predicted ‘moral panic’, we might ask, to what extent is this speculation idly prescient or actively self-fulfilling? The comment may only have picked up on a consensual ‘vibe’, but what if it hadn’t? Media confirm, spread and consolidate cultural perceptions – even amongst those who were there to experience the event. Their predictions have repeated if unpredictable effects.

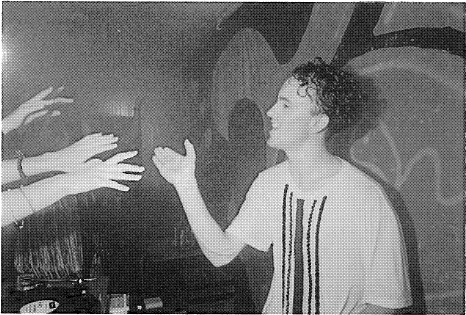

Plate 7 DJ Danny Rampling and his devotees at Shoom just after the club changed its name to Joy because it had received too much media exposure. (Photograph: David Swindells)

The second distinguishing feature of Shoom’s listing is that it publicized the secrecy of the night’s location; it promoted the club by withholding its address. Tantalizing statements like ‘if you’re lucky enough to know the location of this underground party’ candidly play on the ‘hip’ capital of being ‘in the know’. Mystery locations are one guarantee of being underground and part of the excitement of raves. As raves grew in size and number, listings would announce the event, tell the reader to look out for the flyer upon which was printed a phone number through which they could get tickets, then later get directions to the rave’s location on the day of the events. In order to avoid premature closure by the police, the organizers would indicate only the general whereabouts of the rave until the evening of the event, when they would give out directions that would become more and more specific towards midnight. Computer information phone lines were also an innovation of acid house and rave marketing: when one became a member of a club organization, one received a number to call for information about their forthcoming events.

One Shoom strategy was to refuse access to mass media like television news but to tell niche media like the subcultural consumer press all about it. (In the same way record companies occasionally issue music they know will be banned from television or radio in order to generate more print media attention.) The resulting copy was favourably superlative:

When a BBC camera crew arrived unannounced at Danny and Jenny Rampling’s Shoom night, arrogantly pushing their way to the front of the queue, expecting free entry, they were in for a shock. Jenny showed the direction of the door on the spot … Warehouse parties were all but killed off by overexposure by the media … so a big round of applause goes out to Jenny Rampling. (Soul Underground August 1988)

This event became a key moment in the written and oral history of acid house. Although the reputation of Shoom cannot be wholly explained by the way the Ramplings managed the ebb and flow of information about their club, their gatekeeping is undoubtedly a contributing factor. Like censorship and ‘moral panic’, the practice of advertising the inaccessible plays a media game which is in harmony with underground ideology. It doesn’t betray so much as reveal a mask; it doesn’t double-cross so much as indulge in double entendre. It doesn’t sell out so much as identify the people and places that are ‘in’.

One reason why Shoom did such a good job in managing their own exposure was because they had to. By many off-the-record accounts, ‘ninety per cent’ of the Shoom crowd were taking the drug Ecstasy. Club cultural media could be trusted to handle this information with care; other niche and mass media could not. For example, after Time Out’s club editor, David Swindells, had attended the club, the magazine published a different blurb which judiciously both exposed and protected the club:

Shoom … is providing the appropriate aural (not to say, astral) atmosphere for the euphoric and whooping crowd to take the idea of dancing to its outer limits, way beyond the confines of the dancefloor and the two step shuffle. It has the kind of wild, uninhibited style that you’d normally only associate with mixed-gay trendy nights. (Time Out 16–23 March 1988)

‘Astral’, ‘euphoric’, ‘outer limits’ – the rationale behind these oblique references to drugs is explained by their author in the following way:

In a job like mine, you need to be reasonably conscientious. You want to write about it but not destroy it. Scenes are fragile, bloody small and relatively insignificant. You get to know the people involved, develop a cosy relationship and maybe you don’t write as objectively or journalistically as you should. My job is to tell people what is happening without threatening the scene. (David Swindells, interview: 2 September 1992)

Listings magazines are available from any newsagent, so they manage the flow of information with degrees of cryptic shorthand, innuendo and careful omission. Their gatekeeping can often establish the boundaries of the esoteric, protect the feel of the underground and mitigate overexposure. Flyers, by contrast, follow the movement of people through the social spaces of the city, then attempt to guide them to future locations. Both are integral to the formation of club crowds.

Another micro-medium that requires discussion is pirate radio. Here, I will focus on one case which is particularly revealing of the logics of subcultural capital – the transition of KISS-FM from pirate to legal radio station, from micro- to niche medium. Until 1990, dance music radio was illegal in Britain; the only stations to offer a hundred per cent dance programming were the ‘pirates’. From sharing the same DJ staff through to club tie-ins, reciprocal promotions and overlapping audiences, pirate stations and dance clubs had been entangled in a web of financial and ideological affiliations that went back to the sixties. Before founding pirate Radio Caroline in March 1964, for instance, Ronan O’Rahilly had run the Scene, a fashionable Mod hang-out in Soho. And throughout the 1970–80s, reggae, soul then house music pirate stations organized ‘blues parties’, ‘shabeens’, warehouse parties, clubs and raves (cf. Chapman 1993).

Pirate radio stations have long been positioned as the antithesis of the official, government-funded Radio One. Despite being for-profit narrowcasters, they are cloaked in the romance of the underground. Like fanzines, they are supposed to be the active voice of subcultures and like graffiti or sampling, their acts of unauthorized appropriation are deemed ‘hip’. To a large degree, the stations did indeed cater to those culturally disenfranchised by age and race. The black music press, in particular, championed the pirates; they published listings of their frequencies (even after it had been criminalized), recounted tricks for dodging the police and berated the DTI (Department of Trade and Industry, responsible for licensing the airwaves) as the ‘Department of Total Idiots’ (Touch October 1991; Touch March 1991). Moreover, pirate radio was celebrated as ‘the bush telegraph of acid house – [it] keeps the revolutionaries informed’ (Soul Underground December 1989–January 1990).

The Broadcasting Act of 1990, however, changed a long-standing state of affairs and propelled the pirates in one of two directions. By making it a criminal offence to advertise on pirate radio, many stations were driven from partial to total dependence on revenue generated by advertising clubs and raves. As one pirate DJ explained, ‘club nights have always been our biggest money maker and they can still be advertised – they can’t hold the owners responsible and they have no way of finding the promoter’ (Touch March 1991). The ties between clubs and pirates tightened to the extent that many stations became little more than communication units of the larger club organizations. The stations even took on the names of club nights and raves; for example, in September 1990, ‘Future’ ‘Fantasy’, ‘Friends’, ‘Obsession’, ‘Lightning’, ‘Rave’ and ‘Sunrise’ were all on the air.

The course for a few other pirates, however, was legalization. In London, Manchester and Bristol, for example, pirates with sizeable audiences and sufficient legal and financial backing won licences from the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA). Changes in government policy have generally been forced by the popularity of illegal radio. Radio One was established in 1967 as a reaction to the off-shore pirates, Radio Caroline and Radio London. While the 1990 Broadcasting Act intended de-regulation, the IBA was reluctant to license a dance music station, refusing KISS FM’s first bid in favour of a jazz station to which few people tuned in. (For a detailed account of the politics of Greater London FM radio licensing, cf. Barbrook 1990.)

London’s KISS-FM was the largest and most celebrated instance of a pirate station going legal, and consideration of their transition illuminates the subcultural logic which distinguishes between the thrill of the illicit and the banality of the condoned. Founded in 1985, the pirate KISS was ranked in 1987 as London’s second most popular radio station, after Capital FM and ahead of Radio One, by a poll in the Evening Standard. With the million pound launch of KISS’s legal version in 1990, Rogers and Cowan, its public relations firm, and BBDO, its advertising agency, tried to build on this audience by maintaining what they understood to be the station’s appeal – its underground credibility and ‘street’ feel. They issued six marketing statements including ‘KISS-FM reflects the sound of the street’ and three slogans which declared that KISS was ‘Radical Radio’, ‘The Station on Everyone’s Lips’ and ‘The Voice of the Underground’. While the trade weeklies had no problem in accepting that ‘KISS has deliberately kept its pirate station feel’, most of the youth-oriented press were sure a combination of IB A restriction and business pressure would compromise KISS (Music Week 17 November 1990). Even amid the positive reviews, they repeatedly expressed doubt that the station could ‘walk the fine line between credit and credibility’ (City Limits 30 Aug.–6 Sept. 1990). KISS had always been ‘commercial’ but with licence fees, taxes and corporate backers, it would need to make more. Contrary to assumptions about the conservative role of bureaucratic bodies like the IBA, however, KISS-FM’s ‘Promise of Performance’ contract went some way toward insisting that KISS maintain its underground feel. Their licence stipulated that at least fifty per cent of their playlist be new material, that is, pre-chart, on general release but not in the top forty, pre-release or unreleased in Britain at the time of broadcast (IBA document 1990).

Nevertheless, Lindsay Wesker, KISS’s head of music and main spokesman, spent much of the station’s first year of legal operation juggling the ideological contradictions between subcultures and commerce. Wesker repeatedly told the press that KISS both maintained its subcultural feel and offered a substantial target audience attractive to advertisers, that they were both uncompromising in their search for authentic dance sounds and unswerving in their accumulation of socially active listeners between fifteen to twenty-four years. Previously, legal radio stations hadn’t bothered with ‘hip’ subcultural trappings because they enjoyed monopoly or duopoly markets. With KISS (and other incremental dance stations around the country), British radio had to confront the discursive inconsistencies for the first time. As the record and publishing industries had been successfully negotiating the knotted problems of youth niches and subcultural capital since the sixties, it is not surprisingly that KISS-FM’s main financial backers were three publishers and a leisure group which grew out of a record company.* Moreover, their first key advertiser was the American Coca-Cola Ltd. British advertisers are notoriously suspicious of radio advertising (radio then attracted only two per cent of advertising revenues), but Coca-Cola had faith in the youth niche markets delivered by radio (particularly as their main rival, Pepsi, had an exclusive contract with KISS’s main competitor, Capital FM).

Five years after its launch, KISS-FM continues to promote dance events and club nights. They have club and rave listings several times throughout the day and advertisements at night and at the weekend when rates are cheaper. KISS represents a sizeable section of the London dance scene. It gives key club DJs their own evening shows in which to play a conspicuously high number of ‘exclusives’ and promote their own club nights. It also has a substantial portion of clubbers and ravers among its listeners. To talk about certain London dance subcultures without reference to KISS would be to omit a main point of reference, source of information, assimilator of sounds and disseminator of underground ideology. Of course, every change of staff, playlist policy or mode of address is usually met with accusations that KISS is getting less and less ‘street credible’ and sounding more and more like Radio One. Although many clubbers and ravers see themselves as further underground than this ‘voice of the underground’, it is worth noting the way in which a station with a weekly reach of a million listeners employs the rhetoric of subculture and maintains so many club cultural links.

Finally, mention should be made of a new micro-medium which has come to the fore since I completed my research but has implications for the future development of music cultures: the internet. Electronic mail is an obvious improvement on traditional ‘snail mailing’ lists in so far as it is faster, cheaper and potentially interactive. The mailing list of ‘UK-Dance’ set up by Stephen Hebditch in 1993 is used by a small number of organizers to publicize clubs, by a larger number of clubbers to discuss forthcoming events and to review releases for one another, and even by a few ex-clubbers to discuss aspects of rave culture other than going out. The discussions here have the same personal flavour as the fanzines, with many being about drugs or the practicalities of dance events (like the lack of available water or the repulsive state of the portable toilets). Although this mailing list spawned an archive site, ‘UK-Dance on the World Wide Web’, the most elaborate site – and probably the first on the net – was Brian Behlendorf’s techno/rave archive. First set up at Stanford University, then on Behlendorf’s own San Francisco-based server called ‘hyperreal’, this world wide web site includes pictures of rave flyers, discographies and sound samples, as well as the opinions of its various experts and users.

Despite the preponderance of Americans on the internet, Behlendorf estimates that some forty per cent of visitors to his site come off British or European servers, undoubtedly because interest in techno music and raves is much more widespread in Europe (e-mail to author, 1994). But there is also a high percentage of non-British, particularly American, users of the ‘UK-Dance’ site. In fact, many British net surfers spend as much, if not more, time communicating with European and American ravers than with their clubbing compatriots. The internet’s quintessentially global character, its obliviousness to geographical distances and national borders, will condition the nature of its effect on music communities. As one Finnish raver on the UK-dance mailing list wrote: ‘communicating with people around the world has influenced my musical tastes … but the net hasn’t done much for me as far as supporting the local scene goes’.

All the micro-media discussed here have different influences and impacts: the most venerated are not necessarily the most actively engaged in convening crowds or shaping subcultures. Whatever their exact effects, they are more than just representations of subcultures. Micro-media are essential mediators amongst the participants in subcultures. They rely on their readers/listeners/consumers to be ‘in the know’ or in the ‘right place at the right time’ and are actively involved in the social organization of youth.

Niche Media: the Editorial Search for Subcultures