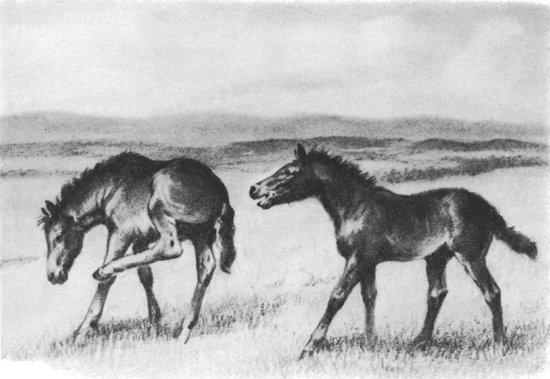

THE LITTLE reddish-brown colt stopped nibbling grass. He lifted his head high and sniffed the noonday wind. His nostrils fluttering, he sniffed again. Long, quivering sniffs. A man and a boy were coming up the road. They must have journeyed a long way, for their man-smell was almost blotted by dust.

Now the colt whinnied sharply. Instantly a bigger colt, scratching at a green-head fly, alerted. He alerted so suddenly it seemed as if his name had been called out. He trotted over to the little colt, touching noses with him. Then his ears pricked as he caught the sound of booted feet walking slowly, and of bare feet running. Now he, too, knew that strangers were coming up the road.

Wearily, wearily the man’s steps dragged. As he reached the fence, he rested his arms on the top rail and his whole body seemed to go limp. The boy leaned against the fence too, but not from weariness. His was an urgent desire to get close to the colts. The boy’s blue linsey-woolsey shirt was faded and torn, and his breeches, held up by a strip of cowhide, were gray with dust. His stubbly hair was straw-colored, like a cut-over field of wheat. Everything about him looked dry and parched. Everything except his eyes. They peered over the fence with a lively look, and his tongue wet his dry lips.

“You!” he said with a quick catch of his breath, as the littler colt came over and gazed curious-eyed at him. “I could gentle you, I could.”

The man sighed. “We’re here at last, Joel. We can put our bundles down and rest a spell before we see if Farmer Beane’s at home.”

The boy had not heard. He just stood on tiptoe, holding his bundle and gaping at the colts as if he had never seen their like before. “That little one . . . ” he whispered.

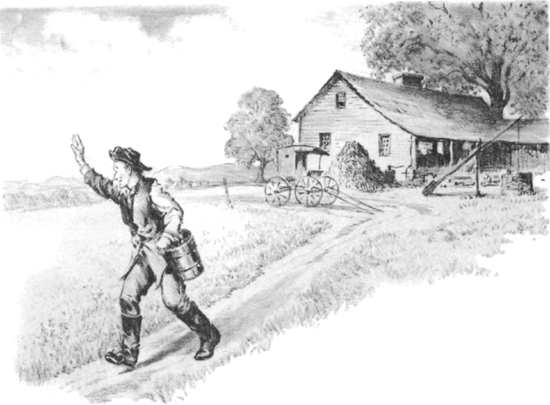

Just then a door slammed shut, and from the house beyond the meadow a farmer in his working clothes started down a footpath toward them. “How-de-do!” he called out as he came closer. Two rods from them, he shaded his eyes and stared intently.

With a whistle of surprise he stopped in his tracks. “Great Jumping Jehoshaphat!” he shouted. “If it ain’t Justin Morgan, schoolmaster and singing teacher! Why, I’m as pleasured to see you as a dog with two tails.” He set down a bucket he was carrying and shook hands across the fence. “Who’s the fledgling you got with you?” he asked, pointing a thumb toward the boy.

“This lad is Joel Goss, one of my scholars. I board with his parents,” the schoolmaster explained. “And when I mentioned that I’d be going off on a junket till school starts, I could see he wanted to traipse along. Joel,” he said, putting his hand on the boy’s shoulder, “I’d like you to meet Farmer Beane, an old neighbor of mine.”

Reluctantly Joel turned from the colts to face the farmer. He had never been introduced before. It made him blush to the roots of his sunburnt hair.

“Cat got your tongue, boy?” the farmer said, not unkindly. “Or be you smitten on the colts?” And without waiting for an answer, he popped more questions. “Where in tarnation you two come from? You hain’t come all the ways from Randolph, Vermont, to Springfield, Massachusetts, be you?”

Justin Morgan nodded.

“Sakes alive! You must be all tuckered out. Why, even as the crow flies, it’s over a hundred mile down here. You didn’t walk the hull way, I hope.”

The schoolmaster took off his hat and ran his fingers through graying hair. “Yes, Abner; that is, most all the way, except when Lem Tubbs and his team of oxen gave us a short haul into Chicopee.”

“Well, gosh all fishhooks, let’s not stand here a-gabbin’. Come in, come in! The woman’ll give us hot cakes and tea. I’ll bet Joel here could do with some vittles. He’s skinny as a fiddle string. Come in, and by and by we can chat.”

All during the conversation the colts had been inching closer and closer to Farmer Beane. Now they were nipping at his sleeves and snuffing his pockets.

“These tarnal critters love to be the hull show,” chuckled the farmer, reaching into his pockets. “If I don’t bring ’em their maple sugar, the day just don’t seem right to them. Nor to me, neither.”

Justin Morgan steadied himself against the fence. “Abner,” he said, “before Joel and I sit down to your table, it seems I should tell you why I’ve come.” He paused, nervously drumming the top rail for courage. After a while he looked up and his glance went beyond the meadow and the rolling hills. “I’ve come,” he swallowed hard, “because I’ve a need for the money you owed me when I moved away to Vermont.”

There was a moment of silence. It was so still that the colts munching their sugar seemed to be very noisy about it. Joel thought of the bright red apple he had eaten last night. He wished now that he had saved it for them.

It was a long time before the farmer could answer. Then he said, “You’ve come a terrible long way, Justin, and ’tis hard for me to disappoint you. But me and the woman have had nothin’ but trouble.” He began counting off his troubles on his fingers: “Last year, my cows got in the cornfield and et theirselves sick and died; year afore that, the corn was too burned to harvest; year afore that, our house caught afire. I just hain’t got the money.”

Master Morgan’s shoulders slumped until his homespun coat looked big and loose, as if it had been made for someone else. “I’d set great store on getting the money,” he said. “I’ve got doctor bills to pay and . . . ” He took a breath. “For years I’ve been hankering to buy a harpsichord for my singing class.”

There! The words were out. He spanked the dust from his hat, then put it back on his head and forced a little smile. “Don’t be taking it so hard, Abner. I reckon my pitch pipe can do me to the end of my days.” His voice dropped. “And maybe that won’t be long; I feel my years too much.”

The farmer pursed his lips in thought. “Justin,” he said, “I ain’t a man to be beholden to anyone. Would you take a colt instead of cash?”

Joel wheeled around to see if Mister Beane was in earnest.

“Now this big feller, this Ebenezer,” the farmer was saying as he pointed to the bigger colt, “he’s a buster! He’ll be a go-ahead horse sure as shootin’. If you looked all up and down the Connecticut Valley, I bet you couldn’t find a sensibler animal.” He glanced at the schoolmaster’s set face and spoke more persuasively. “Besides, he’s halter broke! He’d be the very horse to ride to school.”

Justin Morgan shook his head. “No, Abner, I’m but a stone’s throw from school, and a colt would just mean another mouth to feed.”

“Why, bless my breeches,” the farmer laughed hollowly, “if you ain’t a-goin’ to use him, you could sell him long afore you run up a feed bill. Already the river folk got their eye on him. He’ll fetch a pocketful of money. Mebbe twice as much as I owed you!”

The schoolmaster studied his dust-covered boots as if he did not want to look at Ebenezer.

“By Jove,” the farmer added, “I’ll even give you a premium. I’ll throw in Little Bub for good measure.”

Joel tugged at the schoolmaster’s coattails. “Please, sir!” His eyes begged. “I could . . . ”

“ ’Course, he ain’t the colt Ebenezer is,” Mister Beane went on. “He’s just a mite of a thing. But there’s something about those two! They stay together snug as two teaspoons. Scarcely ever do you see one alone.” The farmer spoke more hurriedly now, as if the rain of words might convince where reasons failed. “Eb’s kind of like a mother to Bub. Why, I’ve seen Bub nip Ebenezer on the flank, and that big colt knew ’twas just in fun! He’d turn right around and nuzzle the little one. If’n you didn’t know, you’d actually think the colt was his’n!”

Master Morgan laughed a dry laugh, like wind rustling through a cornfield. “I don’t need two horses any more than I need water in my hat! They would be two more mouths to feed.”

Joel broke in timidly. “I reckon I could feed and gentle Little Bub?” he pleaded.

The schoolmaster’s eyes smiled down at the boy, ignoring the question. “In the hills of Vermont,” he said kindly, “farmers want big, strong oxen. Not undersized cobs like Bub.”

The smaller colt stood so close to the fence now that Joel reached out and touched the tremulous nose. It felt like plush.

“Ee-magine that!” clucked the farmer. “The little nipper didn’t even snort. Your Joel’s got a way with him, he has. Wouldn’t wonder if he could gentle the critter.”

He turned to Ebenezer now and picked up his feet, first one and then another. “Look-a-here, Justin, see how mannerly this feller is! As a schoolmaster, you know good dispositions from bad.” Next he pressed Ebenezer’s muscles, and then lifted his upper lip to show the strong teeth.

At last he turned to the little colt. “Ye’re right about this ’un,” he said. “Bub is only pint measure. But he’s mannerly, too. Except . . . ” He hesitated. “Yep, I may as well tell ye—’cept when he sees a dog. He can’t abide ’em! They make him mad as any hornet. He strikes out at ’em with his feet, and squeals and chases ’em until they go lickety-split for home, tails tucked clean under their bellies.”