MAN AND boy and colts all seemed to fit together now, and to feel at home in the green hills. On and on they went, past tiny towns perched high on mountain shoulders or nestled snug in the crook of a stream. Nearly always a church spire rose from the cluster of homes and sharpened itself against the sky.

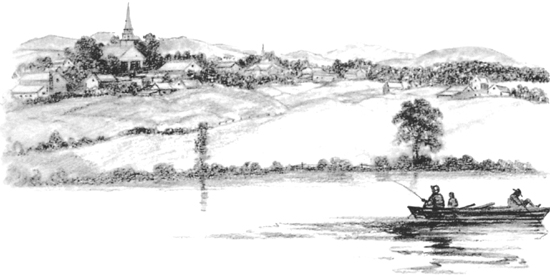

They walked in the dark of woods and in the sunlight of farm clearings. They saw pigs wearing wood collars to keep them from rooting under fences and wriggling away. They saw flying squirrels leaping from tree to tree, and black bears eating butternuts, and brown weasels scuttling in the underbrush. They saw small lakes like polished mirrors, and fishermen in boats, and hawks gliding in for a landing.

They heard the bleating of sheep, and wild geese honking, and beavers slapping their tails against the water. They heard the military music of waterfalls and the cradlesong of brooks.

They clattered over bridges with the printed warning:

WALK YOUR HORSES

“That’s all we’ve been doing!” Master Morgan would say to Joel with a smile.

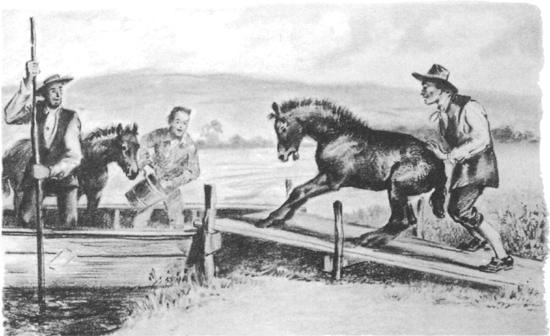

Occasionally they ferried across swift-flowing streams. Ebenezer was struck with terror at sight of a ferry. He had to be bribed with corn and pushed to get on. Then he stood stiff-legged and quivering until the trip was over. But Little Bub sauntered aboard as gaily as a youngster going on a picnic. One ferryman nudged Master Morgan and laughed, “It’ll be sixpence apiece for you and the big colt, but I’ll let the lad and the runt go over for twopence, same as a goat.”

Through deep grass, across broken country, along the gravelly bed of creeks, uphill and downhill, the little procession ate up the slow miles. Six days a week they pushed and plodded. But on the Sabbath they did not travel at all, for there was a law in Vermont forbidding it.

Instead, the schoolmaster and the boy found the nearest meetinghouse and tied the colts to the hitching rack. Then shyly they stepped inside the cool, musty building and joined the worshipers.

Crowded into a box pew, Joel tried to listen to the preacher’s voice running on, but it lulled him like the faraway droning of a bumblebee. His thoughts wandered, lifting him out of doors. He was at the hitching rack with the colts, tied alongside the work horses and oxen that had brought wagonloads of families to church. And they were all nodding and dozing in the warm sunshine as if they had known each other forever.

During one drowsy sermon, the preacher suddenly brought his fist down with a bang, and the voice that had been so low exploded in a mighty roar:

“Awake, thou that sleepest,

For the day of salvation is nigh!”

Heads everywhere in the meetinghouse fairly jolted to attention, while in the churchyard Little Bub let out a high bugle with that funny little rumble afterward.

Joel had to smother his laughter, for the tithingman stood ready with his staff to tap anyone acting unseemly.

When the service was over at last, the worshipers greeted Master Morgan and Joel and often invited them to join in the noontide meal. “We figure you folks come a-traveling a good long ways,” some motherly person would say. “You must be mighty hungry. Come! Follow us out under the elms.”

Like a flock of hungry starlings, the congregation scattered on the church lawn. From picnic hampers came thick slices of ham, homemade cheese, and brown-bread sandwiches filled with a rich layer of apple butter.

The boy and the master always ate their fill, and afterward the same motherly person would wrap up a nice cold snack of leftovers for them to take along.

It took nearly a month to walk the hundred miles and more back home. The days were growing shorter, and to Joel the sun seemed far away and choosy. It picked out the blobs of scarlet sumac and the yellow maple leaves, and then hung a misty haze over the rest of the world.

Now that the trip was almost over, the schoolmaster had little to say. He seemed to need all of his strength to put one foot ahead of the other. It was on a frosty twilight in September that they came to the junction of the Connecticut and the White rivers.

“At last, we are almost home! At last we leave the Connecticut!” the schoolmaster sighed, raising an arm in farewell. “When the Indians named it the Long River, they were right as a bonnet in church.”