THE NEXT morning Joel’s mother set down a big platter of fried ham and oatcakes in front of him, as if already he were a visitor instead of family.

Joel smiled up at her. “I feel like Preacher Clapsaddle,” he said, “come to pay a call.”

“See that you stow away your food like Preacher Clapsaddle!” his mother replied, with a catch in her voice.

Then they both laughed at the remembrance of the preacher eating so heartily that he kept tucking his beard into his mouth along with the food, and had to pull it out again and pat it dry.

“How nice it is,” Joel thought, “that Ma and I can laugh even when we feel all pinched up inside.”

Mister Goss clumped in then, and breakfast became a business to be finished with dispatch. “Sniggering and tomfoolery have small place in this workaday world,” he said, shaking a forefinger. “Won’t be no such nonsense at Miller Chase’s, I kin promise you that!”

The meal was eaten in silence, with only the sounds of chewing and swallowing and Mister Goss’s pewter cup brought down sharply on the table.

At last the father wiped his mouth and stood up to go. He motioned to Joel to follow, and without a word the man and the boy marched out into the morning sunshine and set off for Chase’s Inn.

Only once did Joel turn back. His mother, looking very small, was waving her apron at him, a white flag of courage.

It was almost a mile to Chase’s Inn, and all the way Joel walked with head bent, letting dreams take over his thoughts. He made believe the colts were right behind him. Once he imagined he heard Ebenezer neighing and Little Bub sending forth his high notes which died out in that low rumble. He tried hard to listen, but Mister Goss was ranting on about the sorry condition of the Jenkses’ fence, and Joel could not be sure.

As they passed the Jenkses’ house, he hoped for a glimpse of the schoolmaster, but the only sign of life was a yellow hound pup sniffing along a hedgerow. Joel said to himself, “Little Bub hain’t going to like that hound-dog, if what Farmer Beane told us was sure enough true.”

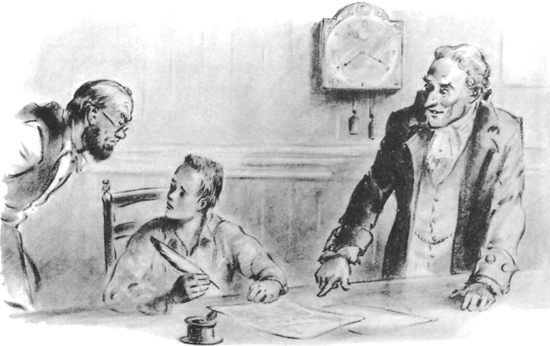

As luck would have it, Thomas Chase was alone, working on his accounts, when Joel and his father walked into the office of the inn. He paused, quill pen in hand, and looked up from under his bushy eyebrows.

“Wal,” he smiled, noting the worried look on Joel’s face, “ain’t nothing in the world so bad nor so good as it seems. Now what kin I do fer you two?”

Mister Goss wasted no time on pleasantries. He went right to the point. “I’d admire,” he said, “to have you take on my Joel as your apprentice. With a sawmill and an inn to tend, you need a stout lad to help. Joel here will be handy as the pocket on your coat!”

The miller let his cool gray eyes travel over the boy with interest. Only this morning he had received a big order for barrel staves and hoops from the West Indies. Besides, Mistress Chase had been snappish of late. A likely lad—one who could buckle down to work—might make things easier all around.

“Hmmmm,” he said, hedging for time. “It’ll take a lusty lad to work by day and go to school by night, like the law requires.”

Mister Goss thumped Joel on the back. “The boy ain’t what you’d call a strapper—that is, not to look at—but he’s tough as leather.”

“Hmmmm!” the miller said again, trying to compare this boy with an overfat one who had come to see him just last evening. He put down his pen and looked earnestly at Joel.

“Y’know, son,” he said, “’twouldn’t be no snap around here. There’s an awful lot of hand sawing to do, and Mistress Chase is mighty smart at thinkin’ up chores. A boy’d have to be strong as a bear and quick as a cat.”

“Show him your muscle, son. Make a fist and show him.”

Joel winced. His eye fell on the wall clock behind Mister Chase. The hour hand pointed exactly to seven. Below the dial the pendulum was hidden in a glass case painted with flying white doves, and the words, “Time is fleeting.”

Joel obeyed his father. What did it matter if Miller Chase laughed at his puny arm? In a few seconds it would be all over. He made his fist and flexed his muscle, while his mind repeated the words, “Time is fleeting, time is fleeting, time is . . . ”

At last he brought his gaze away from the clock. To his surprise, the miller was not laughing. His gray eyes were filled with kindness. “Boy,” he said, “I recollect when I was a youngling with no more muscle than you got. But I was full o’ spunk, and for a word o’ encouragement I could do a man’s lick of work.”

Joel smiled in relief. He heard his father cough hesitantly, then heard his voice come, oily nice. “Uh . . . Chase . . . uh . . .. ah . . . stands to reason Joel could saw a bit o’ lumber for my use if’n it didn’t interfere with his regular labors?”

Mister Chase was listening with only half his mind. Suddenly he wanted this boy. He had always hoped for a son of his own and there was something about Joel, not just the gangly growing look, but something about the eyes that he liked. A kind of awareness, like a startled deer. Yet there was trust in them, too. Yes, here was a lad he would be proud to look upon as his own. “If the boy be willing,” he said slowly, thoughtfully, “it would very well suit me to take him.”

“Ahem . . . Chase . . . and about that free lumber?”

The miller waved his hand impatiently. “Yes to that, too. Now let’s step over to the Justice of the Peace and have him draw up the papers all proper-like.”

“What papers?” a high, sharp voice demanded. It belonged to Mistress Chase, who swept into the room wearing a red wrapper and a scowl that said, “Ain’t nothing goin’ to happen around here without my say-so.”

Thomas Chase turned around. “This boy,” he explained to his wife, “is ready to be parceled out. He’ll be considerable help to both of us.”

To the man’s amazement, his wife nodded vigorously, and the white flounces on her cap went up and down like waves billowing. “Aye!” she agreed. “The skinny ones be quicker.”

All this while the big hand on the clock had moved but five minutes. Joel swallowed hard. In five minutes he had lived a whole lifetime! In five minutes he had grown from boy to man.

Woodenly he followed along after his father and the miller as they walked through the public room of the inn and out of doors and down the road to the small weathered house of the Justice of the Peace.

The office of the Justice was a crowded-in place—the desk too big for the room, and the chairs set at awkward angles, so that Joel stumbled over one and almost fell flat. There was a clock here, too, a big one, very plain, without doves or cupids or words of wisdom. Its tick was loud and doleful as it tolled the seconds.

The Justice, a black-frocked spider of a man, listened to Mister Chase’s story and began at once to fill in the blank spaces on a printed sheet. After some time he peered over his spectacles at Joel and said in a whiny voice, “Boy! Repeat after me: I, Joel Goss . . . ”

“I, Joel Goss . . . ” came the frightened voice.

The whine went on, “ . . . of my own free will, and by the consent of my father . . . ”

“Of my own free will, and by the consent of my father . . . ”

“Doth put myself apprentice to . . . ”

“Doth put myself apprentice to . . . ”

“Thomas Chase of Randolph, Innkeeper and Miller . . . ”

Joel turned white. He felt as if his whole body were going through the sawmill, being ground into bits. He grabbed at his father’s sleeve. But Mister Goss stood straight and unmoving, as if no more than a fly had lit on him. A sob meant to be a silent one escaped the boy as he repeated:

“Thomas Chase of Randolph, Innkeeper and Miller . . . ”

The voice of the Justice twanged on: “ . . . . until the full term of seven years be compleat and ended.”

“Seven years!” Joel cried. And “Seven years! Seven years!” the clock tolled. The boy stared at the clock. Things were happening to him. Without a hand touching him, he was being shoved down the years.

“During the aforesaid term,” the Justice was saying, “I, Joel Goss . . . ”

“During the aforesaid term, I, Joel Goss . . . ”

“Shall never absent myself day or night without leave . . . ”

Joel imagined he saw his mother’s face now, wiping away a tear. He saw her crying into Little Bub’s mane, just as he had done. His words came without his willing them.

“Shall never absent myself day or night without leave . . . ”

“But shall always . . . ”

“But shall always . . . ”

“Obey my master’s commands . . . ”

“Obey my master’s commands . . . ”

“And keep his secrets.”

The Justice stopped to scratch his ear with the goose-quill pen. Then he quickened his pace and went on without pausing now for Joel. “Said master shall teach said apprentice the art or mystery of a sawyer, and shall provide for him sufficient meat, drink, apparel, lodging, and washing befitting an apprentice, and shall send him to school every winter at night.”

He took a deep breath, then plunged rapidly on, chanting the familiar words until they ran together without meaning. “At the completion of said term, the master shall provide for the apprentice one new suit of apparel, four shirts, and two neckletts.

“In witness whereof Philip Goss, Thomas Chase, and Joel Goss have put their hands and seals this twenty-fifth day of September, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-five.”

A spidery hand held out the goose-quill pen to Joel. And the whiny voice said, “Now, boy, sign here, in the presence of your father and Thomas Chase. and before me, Jacobus Spinks, Justice of the Peace for the village of Randolph in the County of Orange in the State of Vermont.”

“Sign here!” ticked the clock. “Sign here! Sign here!”

Again Joel turned to his father, eyes imploring: “Do I have to, Pa?”

But again there was no answer. Mister Goss’s arms were folded across his chest and his gaze held to a fixed spot on the ceiling.

At last Joel picked up the pen and curved his thumb and fingers about it. He sat down on the chair that the miller pulled up for him, and put his arm on the desk. His eye followed the black-nailed finger pointing to a dotted line.

“Yes, Mister Spinks,” he murmured, “I see the place you mean.” And with trembling hand he wrote in his round childish scrawl:

Joel Goss