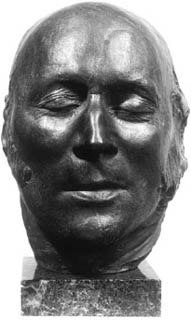

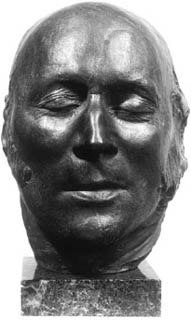

Constable’s death mask

WITH THE NEW Year past, it was back to the easel. The canvas Constable worked on was to be called Arundel Mill and Castle. Mills never ceased to interest him and perhaps as he painted he heard the wheel going round, the rush of river water, the stones grinding within. While staying with the George Constables in July 1835 he had sat on the banks of Swanbourne Lake near Arundel and sketched this ancient powerhouse,1 which was far older than the stage-set castle. In 1836 he had borrowed back the sketch – a gift to George Constable – saying young John wanted him to make a painting of it, but The Cenotaph had come first.2 In mid-February 1837 he wrote to the Arundel brewer telling him he was indebted to him for the new work, ‘a beautiful subject … It is, and shall be, my best picture.’ He had six weeks before the Academy exhibition and felt easy about completing it in time. In the Mill and Castle he used a scene which he had told Leslie several years before was a wonderful natural landscape – ‘the trees are beyond everything beautifull’. One can see in the painting hints of his early addiction to Gainsborough, but even more, and less happily, reverberations from his other old hero, Rubens, to whom many of the painterly effects seem indebted. Not only Arundel Castle but the Chateau de Steen looms over Arundel Mill. There are of course Constable motifs – the boys fishing in a little creek at the lake’s edge remind us of other boys fishing in the Stour. Yet in recovering such things he gave the impression of trying too hard to improve on his old works, to improve the unimproveable, and the result was unnatural. The Swiss art historian J. Meier-Graefe later wrote that Constable, in his last larger pictures, ‘felt expression slipping away from him, and tried to indemnify himself by exaggeration of method’. Consequently he lost the freshness that existed in his sketches.3 The word ‘mannered’ once again came to mind. Even Constable began to have doubts about his ‘best picture’. On 25 February he told Leslie that he had been ‘sadly hindered … my picture is not worth any thing at the moment’.

Titian, not Rubens, was in Constable’s thoughts as he set up a scene for the Academy’s Life students to draw. He took over from Turner as Visitor at the end of February, and he wrote to Leslie that he would be ‘engaged with the “Assassin” all the following week’ – that is, with the figure of the murderer in Titian’s St Peter Martyr. A man named Fitzgerald was to be his model for the assassinated Dominican and another named Emmott the fleeing murderer, ‘an obliging well behaved man … who is anxious for a turn at the Academy’. He had to hand a print of the same subject based on a painting by Jacobello del Fiore, done five years before the Titian. He had made a point in his landscape lectures of the Titian’s significance in the process by which landscape painting unlinked itself from history painting and became an independent branch of art.

Constable’s tour of duty lasted until 25 March. He looked after the Life students from five p.m. until nine p.m. every evening in front of a model lit by oil lamps. The scene he set to follow the Assassination required a young woman. Etty, naturally interested in helping out, sent a note which amused the recipient:

Dear Constable,

A young figure is brought to me, who is very desirous of becoming a model. She is very much like the Amazon and all in front remarkable fine.

The apprentice model was seventeen. For her, Constable put aside a more experienced female named Welham who had been promised the job but had in some way misbehaved; moreover (he told Leslie) she was ‘a sad story teller, and gossip, & old and worn out in figure’.4 Clearly not remarkably fine.

Looking after the Life class was a strenuous job after a day’s painting. It was a long winter, with deep snow in Charlotte Street, the fogs thick with coal smoke. There was much influenza about and Constable advised Samuel Lane to keep his children at home because of the bitter weather – ‘nothing breeds whooping cough so much’. His own family escaped illness although he worried about young John, ‘the most tender of us all’, still working hard for his Cambridge entrance. His girls were all well and happy at ‘that excellent woman’s, Miss Noble’, where Mrs Roberts went to see them from time to time. He attended the first RA general meeting to be held at ‘the new house’. Many thought William Wilkins’s building too low-key and by no means big enough for the National Gallery (in the west half) and the Royal Academy (in the east), crammed in together.5 But Constable called it ‘very noble’. His last Life class session took place in Somerset House on 25 March, a Saturday. He treated it to his usual humorous interjections. Richard Redgrave, who was there along with Etty, painting from the model, said that Constable ‘indulged in the vein of satire he was so fond of’.6 At the end of the evening – not just his last evening as Visitor but the last such get-together in the old house – he gave a brief talk to the students about what caused the arts to prosper or fail. One factor that led to success was the right sort of instruction; one that led to disappointment was trust in false principles. The Academy had advantages as the cradle of British Art; students shouldn’t rush to European schools instead. The best school of art existed where the best artists lived, not where the largest number of old masters were displayed. Some people thought the French were best at drawing. Yet remember what Stothard had said: ‘The French are very good mathematical draughtsmen, but life and motion are the essence of drawing, and their figures remind us too much of statues.’ Constable asked the students to show in their work that they had imbibed the Academy principles which would honour the new establishment and their country, then he thanked them for their diligent attention during his Visitorship. At this the students stood and cheered him heartily.7

After this he had a busy few days. Among his visitors in Charlotte Street was a recent Academy student, Alfred Tidey, who had watched him working on The Cenotaph. Tidey became a painter of miniature portraits, his subjects including Minna and Charley. On 28 March Tidey found Constable happily absorbed in his Arundel Mill and Castle. He gave it a touch here and there with his palette knife and then stepped back to judge the effect, saying, ‘It is neither too warm nor too cold, too light nor too dark, and this constitutes everything in a picture.’ Constable asked Tidey to stay to dinner and answered questions about the Academy’s new quarters by sketching a rough floor plan.8 On the following day Constable wrote to Lucas about the Salisbury Cathedral mezzotint; he was particularly pleased with the rainbow, which they had been fussing over. He said that he was planning to go to a general assembly of the Academy the next evening, Thursday, and would dine on Saturday with John Fisher’s father at the Charterhouse, the school and almshouse in a former City monastery.9

On the Thursday Constable met Leslie at the Academy and after the assembly walked part of the way home with him. It was a fine night but very cold. In Oxford Street they heard a child crying and Constable crossed the street to see what was wrong. It was a little beggar girl who had hurt her knee. Leslie watched as Constable gave her a shilling and some sympathetic words. These, Leslie said, ‘by stopping her tears, showed that the hurt was not very serious’. As they walked on, Constable – perhaps thinking about the giving of money – complained about some losses he had had recently, small enough but a nuisance because the people involved took advantage of his good feelings. Constable had gone well out of his way for Leslie but they parted cheerfully at the west end of Oxford Street to take their separate routes home.10

On the last day of March he worked on Arundel Mill and Castle; it would soon have to go to the Academy exhibition. Several people who called in Charlotte Street had the impression Constable wasn’t well, but put the malaise down to his being cooped up in his painting quarters, worried about his picture. In the evening he went out on an errand for his favourite charity, the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution. He got home about nine and ate a good supper. At bedtime, however, he said he felt chilly. He asked for his bed to be warmed; the maid thought this was unusual for him. From ten until eleven he read in bed as he always did. On this occasion he was reading Robert Southey’s Life and Letters of Cowper – William Cowper, poet of religion and nature, as far as Constable was concerned a fellow spirit, author of ‘John Gilpin’s Ride’ and ‘The Task’ (which Constable particularly liked). In a letter to his friend the Reverend John Newton (3 May 1780) Cowper wrote:

I draw mountains, valleys, woods, and streams, and ducks, and dabchicks. I admire them myself, and Mrs. Unwin admires them; and her praise, and my praise put together, are fame enough for me … I amuse myself with a greenhouse which Lord Bute’s gardener could take upon his back, and walk away with; and when I have paid it the accustomed visit, and watered it, and given it air, I say to myself – ‘This is not mine, it is a plaything lent me for the present; I must leave it soon.’

After Constable had fallen asleep the maid removed his candle.11

Because he had rented out much of the upstairs of the Charlotte Street house to help cover the costs of Well Walk, he and his son John were using two adjoining bedrooms in the attic.12 Young John had been at the theatre and when he got home and went to bed, he heard his father call out. Constable was in great pain and felt giddy. His son suggested a doctor be called but Constable said no. He agreed to take some rhubarb and magnesia; this made him feel sick. He then drank some warm water, which made him vomit. The pain got worse. Constable asked John to get hold of their neighbour, Mr Michele, a medical man. He moved from his bed for a while to an upright chair, then back to bed where he lay on his side. By the time Michele arrived, Constable seemed to have fallen asleep, so his son thought, although in fact he had lost consciousness. Michele said brandy was needed as a stimulant. The maid ran downstairs to get some, but she was too late. Young John heard Constable gasp several times and then, nothing – he had stopped breathing. His hands became cold. Half an hour after the onset of the pain he was dead.13

Constable’s trusted messenger Pitt came to Leslie’s house early the next morning. It was 1 April. Leslie saw Pitt from a bedroom window as he was dressing and went downstairs, expecting to be handed a note from Constable, perhaps an invitation.14 But the message was to say that Constable had died during the night. Leslie and his wife hurried to Charlotte Street. They found the painter lying in his little attic room, looking as if he were asleep, with his watch still ticking on the bedside table and a volume of the Southey Life of Cowper alongside it. Among the many engravings hung on the walls was a print near the foot of the bed that Samuel Rogers had lent him of a moonlight scene by Rubens.15

*

Constable’s death mask

Leslie remained for the rest of the day. Several death masks were made while he was there. A post-mortem was conducted by Professor Partridge of King’s College in the presence of Michele and George Young, the surgeon who had given Constable advice about how to present his Hampstead lectures. The results of the post-mortem were inconclusive. The doctors found no indication of any disease that might have killed him. His pain was thought to be from indigestion.16 Michele later told Leslie he thought that if the brandy had been given promptly it might have kept Constable alive. Nowadays we know that indigestion-like pains – ‘heartburn’ – can be signs of what is in fact a heart attack. We also know that rheumatic fever, which Constable had suffered a severe bout of, can do serious cardiac damage, can indeed be life-threatening: Dr Evans of Hampstead thought Constable never fully recovered from his rheumatic fever. Some sort of heart failure was generally suspected by commentators in the press. The Morning Chronicle’s short obituary on 3 April said the cause of death was ‘an enlargement of the heart’. The Morning Post declared that Constable died of ‘an affection of the heart’. On 9 April Bell’s Weekly Messenger said the cause appeared to be ‘spasm of the heart’. One other condition that might be taken into account was Constable’s proneness to anxiety, which John Fisher had pointed out ‘hurts the stomach more than arsenic’. He might have died of a perforated ulcer, though an ulcer should have given painful signs of its presence earlier on. He might simply have burned out his allotted store of vital spirit.17

For Leslie, the shock slowly accumulated. The suddenness of Constable’s death felt like a blow which at first stunned him and then gave him pain. He gradually learned how much he had lost in Constable, and it was more than he supposed at the time of his friend’s death.

The funeral took place in Hampstead parish church and at the tomb where Maria was buried in the graveyard. His brothers, Golding and Abram, led the mourners. Many of Constable’s friends and Hampstead neighbours were on hand. Of family members, his son John was the most noticeable absentee; he was still overwhelmed by his father’s death and too ill to attend. Perhaps as a child, close to his mother, he had lived with death too long. That most persistent of Constable’s ‘loungers’, the clergyman and amateur artist the Reverend Thomas Judkin, recited the Order for the Burial of the Dead: ‘I am the resurrection and the life … The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away … Man that is born of woman hath but a short time to live … He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower … earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust … Amen.’ Judkin wept over the Book of Common Prayer and his were not the only tears that fell. Constable’s coffin was laid in the tomb alongside Maria’s. Some of the mourners noted again the Latin lines he had borrowed from Dr Gooch and had had inscribed for her on the stone side of the tomb:

Alas! From how slender a thread hangs

All that is sweetest in life.18