‘This really sounds Dickensian, I never thought about this before.’

Alan Moore, The Comics Journal #138 (1990)

Chapter Five of Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s graphic novel From Hell (1989–98) opens by presenting us with the ‘striking juxtaposition’ that Adolf Hitler was conceived just as the Jack the Ripper murders began in London. Using the same technique, it’s a resonant chronological coincidence that simple arithmetic places Alan Moore’s conception around February or March 1953, the very time that Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood produced the parody comic strip ‘Superduperman’ for Mad magazine.

Human beings tend not to have the same neat ‘secret origins’ that superheroes do. Few of us have our lives transformed by a single event that galvanises us and leads us to destiny. That said, the summer’s day when a young Alan Moore first read a British reprint of ‘Superduperman’ was hugely formative, and an idea he had that day would end up defining his early career, transforming the superhero genre and providing a successful template for revitalising a long-running series that spread from comics to television and cinema. If we understand what it was about this eight-page comic strip that engaged Moore, what he understood about its contents and what his response to it represents, we’ll be closer to understanding Moore himself.

‘Superduperman’ originally appeared in Mad #4, published by EC Comics in April/May 1953, and was hugely popular. It was one of the first times the magazine had run a sustained spoof of a specific pop culture phenomenon, a format for which Mad would become famous. As the name suggests, ‘Superduperman’ is a parody of the Superman comic, and at one level it now looks a little hackneyed. Some of the targets are obvious, such as the spoof of Clark Kent’s penchant for changing into costume in a phone booth, while the substitution of the names ‘Clark Bent’ and ‘Lois Pain’ for Clark Kent and Lois Lane, or ‘Captain Marbles’ for Captain Marvel, is not something most adults would find terribly witty. There is far more going on in the strip than that, though. Clark Bent’s fawning devotion to Lois and his compulsive desire to sniff her perfume is far from innocent, while echoing the creepiness of the relationship of the ‘real’ Lois and Clark. By changing the ‘camera angle’ slightly, the fight between Superduperman and Captain Marbles involves everything a similar sequence in the original comics would, while portraying its ‘heroes’ as vain, stupid and violent.

Crucially, some of the jokes in ‘Superduperman’ depend on knowledge of behind-the-scenes drama. Any comics fan back then worth their salt knew that the ‘real’ Superman and Captain Marvel could never meet, because they were owned by different companies. DC published Superman, Fawcett published Captain Marvel. The two superheroes had met in court, though, with DC accusing Fawcett of plagiarism. Shortly before ‘Superduperman’ was released DC had prevailed and Captain Marvel, once the best-selling comic on the market, was forced to cease publication. The confrontation between Superduperman and Captain Marbles was, then, as much a commentary on that court battle as on the conventions of the superhero fight scene.

It matters, too, who wrote and drew ‘Superduperman’; it’s a parody that works because the creators clearly love and understand what they are mocking. The artist, Wally Wood, was one of the stars of the comics industry, and had already worked for three of the biggest names in the business: Timely, Will Eisner’s studio and EC. Harvey Kurtzman was another comics legend, the first editor of Mad, who’d go on to the Playboy strip Little Annie Fanny and was the founding father of a style of comedy now familiar from TV series like Saturday Night Live, The Simpsons and The Daily Show. As actor Harry Shearer put it, ‘Harvey Kurtzman taught two, maybe three generations of post-war American kids, mainly boys, what to laugh at: politics, popular culture, authority figures.’

At heart, what ‘Superduperman’ plays on is that anyone reading a superhero comic is exposed to two parallel narratives. The first is the colourful, escapist adventure on the pages of the magazine. The stories in superhero comics are sprawling, interconnected sagas that often seem circular in nature. The same never-ending battles are fought across decades by different individuals who are startlingly similar to those who came before. The same moves are made, the same betrayals occur, old ideas are spliced together to make new ones. The elaborate soap opera cast lists, continuity and traditions that are often baffling and off-putting to outsiders are utterly immersive for the fans. It is always possible to dig down a little deeper, make another connection, spot one more influence, coincidence or unintended consequence. Whole books have been written about the convoluted history of just one comic book character.

By the age of twelve, Alan Moore was already au fait with the tricks used to lure him back month after month:

my favourite part of the whole comic would usually be the Coming Attractions section at the bottom of the last page. They had all these demented announcements like ‘Superman marries Streaky the Supercat! Not a dream! Not a hoax! Not a Red Kryptonite delusion! Not an Imaginary Tale!’ After a while I figured out that whichever disclaimer they omitted, that was the punch line to the story. Like in the example above, since they hadn’t specifically said ‘not a robot!’ you knew damn well that on the last page of the story either Superman or Streaky, or both, would open up a plate in their chest to reveal lots of little cog wheels and SP-11 batteries.

As above, so below. Like those who consumed ‘Superduperman’, even young readers quickly become aware of comics’ second narrative, as sprawling and convoluted as anything on the page: the real-life history of the industry and the people working in it. Characters like Superman, Batman, Captain America and Captain Marvel have been around since the thirties and forties. Creative teams have come and gone, bringing different styles of artwork and storytelling choices. Mastery of this second narrative, knowing what was going on behind the scenes, is an essential part of becoming a comics fan. It is not enough to know about Superman or Spider-Man, a fan must also know about Siegel and Shuster, Lee and Ditko. Creators like Jack Kirby and Will Eisner are, to a comic fan, as ‘legendary’ as any superhero.

Alan Moore’s description of the shopping trip where he first encountered ‘Superduperman’ is instructive. As he fished through the racks, he found ‘they’d also got a load of the Ballantine Mad reprints, which included I think The Bedside Mad, and Inside Mad, which were reprinting from the Mad comics, rather than from the Mad magazines. And one of these that I picked up, possibly Inside Mad, had got Kurtzman and Wood’s Superduperman.’ At twelve, Moore was already a connoisseur, able to assess a comic’s pedigree and make minute distinctions based on only a few clues. With a limited amount of pocket money, he chose his purchases carefully, and the publisher, writer and artist of the comic were at least as important to him as which characters it starred, or whether the cover or story hook were enticing. And Moore was not unique, he was part of an emerging phenomenon, one that publishers had started to cater for: slightly older, more informed comic book fans.

On both sides of the Atlantic, since the birth of the industry in the thirties, virtually all the men and women making comic books had toiled in obscurity and anonymity. Comics were cheap and ephemeral, and anyone older than a small child reading them was assumed to be illiterate. Most writers and artists were happy to sign over all the rights to their work in return for a fairly meagre, but regular, cheque. There were exceptions: Will Eisner, creator of The Spirit, signed every strip and aggressively marketed himself and his studio. But more typical was Patricia Highsmith, who before she wrote Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr Ripley, had written comics for a number of publishers (including Fawcett), but meticulously avoided referring to the fact, even in private diaries that detailed her affairs and psychiatric problems. Mario Puzo, author of The Godfather, and Mickey Spillane also worked anonymously in comics early in their writing careers. People who worked in comics didn’t boast about it.

It’s fair to say Stan Lee changed that.

Stanley Lieber had done his share of toiling. He had started working at Timely Comics in 1939 as a sixteen-year-old office boy who filled the inkwells for the artists. He wrote his first Captain America story two years later under the pseudonym ‘Stan Lee’, as he hoped to use his real name for more respectable writing. Twenty years later, he was editor-in-chief for the same company, which had changed its name to Atlas Comics in the early fifties and had just done so again, to Marvel Comics. The company was a small one and rarely innovated, but kept a close eye on trends in the market. It had spent the previous few years producing westerns, romance and comics about astronauts.

In the late fifties and early sixties DC, one of the major comics publishers, found success modernising its superhero line, revamping characters like the Flash, Green Lantern and Hawkman, created for the previous generation of children, by giving them new costumes and more modern stories with a science fiction flavour. In 1961, Lee followed the trend, and set about creating a new superhero team for Marvel. Lee and artist Jack Kirby agreed that DC’s heroes were so upright it made them a little boring. Alan Moore concurs: ‘The DC comics were always a lot more true blue. Very enjoyable, but they were big, brave uncles and aunties who probably insisted on a high standard of, y’know, mental and physical hygiene.’ So Lee and Kirby created a group that was literally a bickering family – the Fantastic Four. Moore’s experience was typical of the enthusiasm Marvel generated among its readership. In early 1962, at the age of eight, he had asked his mother to pick up a copy of DC war comic Blackhawk: ‘I told her it’s got a lot of people in it who all wore the same blue uniform. And she went out and came back with, much to my disappointment, Fantastic Four #3 … but of course I soon became completely infatuated … From that point I began to live and breathe comics, live and breathe American culture.’

The Fantastic Four were hugely popular, and were soon joined by Spider-Man, the Hulk, Thor, Iron Man, Daredevil, the X-Men and many more, all of them written by Stan Lee. As Moore put it, the difference between Marvel’s superheroes and those of their rivals was simple: they ‘went from one-dimensional characters whose only characteristic was they dressed up in costumes and did good, whereas Stan Lee had this huge breakthrough of two-dimensional characters. So, they dress up in costumes and do good, but they’ve got a bad heart. Or a bad leg. I actually did think for a long while that having a bad leg was an actual character trait.’ As he later put it, Marvel’s success was down to ‘Stan Lee’s crowd-pleasing formula of omnipotent losers’.

The stories and art were crucial, of course, but what really marked the company’s comics out was that Lee used the covers, captions, letters pages and editorial columns to vigorously and enthusiastically blow his own trumpet. The way he did so was so over the top, so hyperbolic, so reminiscent of Robert Preston’s performance as a garrulous travelling salesman in the Broadway show The Music Man, that it was clearly meant to be impossible to take seriously. So, the cover of the first Marvel Comic read by Alan Moore, Fantastic Four #3, declared itself to be

THE GREATEST COMIC MAGAZINE IN THE WORLD!!

And on the cover of Fantastic Four #41, readers were promised

POSSIBLY THE MOST DARINGLY DRAMATIC DEVELOPMENT IN THE FIELD OF CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE!’

Marvel were moreover canny enough to make sure that all these stories took place in the ‘Marvel Universe’. Spider-Man would swing past the Baxter Building, home of the Fantastic Four, note it had been damaged and speculate on the cause – a caption would helpfully inform readers which issue of Fantastic Four to pick up to find out what had happened. The wartime character Captain America was revived and put in charge of the Avengers, a team initially consisting of Iron Man, Thor and the Hulk, who already had their own monthly comics. You could just read one Marvel title … but why would you when you could read them all?

Lee not only gave the characters nicknames – the Incredible Hulk, the Uncanny X-Men, the Amazing Spider-Man – Marvel Comics were drawn by Jack ‘King’ Kirby, ‘Sturdy’ Steve Ditko, Gene ‘The Dean’ Colan, ‘Jaunty’ Johnny Romita and the like. Together they were the Marvel Bullpen, and the way Stan Lee told it, no other room on earth buzzed with as much creative energy. Not only did the cover of Fantastic Four #10 proclaim

THE WORLD’S GREATEST COMIC MAGAZINE! THE FANTASTIC FOUR. HOLD YOUR BREATH!! HERE IS … ‘THE RETURN OF DOCTOR DOOM!’

but it had a couple of other special guest stars too:

IN THIS EPIC ISSUE SURPRISE FOLLOWS SURPRISE AS YOU ACTUALLY MEET LEE AND KIRBY IN THE STORY!!!

Stan Lee’s relentless showmanship demanded and received ferocious brand loyalty from his readers; as Alan Moore has said, ‘We were wild-eyed fanatics to rival the loopiest Thuggee cultist or member of the Manson Family. We were True Believers.’ In truth, Marvel was a tiny company and Fantastic Four had been a last-ditch gamble. Yet, as novelist Michael Chabon, another Marvel acolyte, put it, ‘Lee behaved from the start as if a vast, passionate readership awaited each issue that he and his key collaborators, Kirby and Steve Ditko, churned out. And in a fairly short period of time, this chutzpah – as in all those accounts of magical chutzpah so beloved by solitary boys like me – was rewarded. By pretending to have a vast network of fans, former fan Stanley Lieber found himself in possession of a vast network of fans.’

For UK readers, the comics themselves were artefacts rocketed from a full-colour fantasyland. The Marvel Bullpen intended their version of New York to be ordinary, just the view as they saw it when they looked out of their window, a backdrop to be overlaid with daydreams of the incredible, amazing and fantastic. For Alan Moore, though, a boy living in an English town where the tallest buildings soared to the height of 115 feet, the Manhattan skyline that Spider-Man swung though, or the Lower East Side neighbourhood the Thing came from, or the Hell’s Kitchen patrolled by Daredevil were themselves all ‘as exotic as Mars. The idea of buildings of that scale, the idea of this modernity that seemed to pervade everything. This was a futuristic science fiction world.’

Merely finding DC and Marvel comics in the UK required a degree of arcane knowledge, as they had no formal distribution. They arrived on freight ships which used tied-up bundles of old magazines as ballast. The bundles were meant to be thrown away, but were sold on to traders by entrepreneurial dockworkers. Seven-year-old Alan Moore had first stumbled across copies of Flash, Detective Comics and other DC titles on a stall ran by a man called Sid in Northampton’s ancient market square, and ever since he’d been back every week.

He certainly understood that there was little chance of finding the best, most recent American comics on the annual family holiday in Norfolk. Every year, Ernest and Sylvia Moore would take their sons Alan and Mike for a week at the North Denes Caravan Camp in Great Yarmouth on the east coast of England. This was around 130 miles from home, the furthest the Moores would typically venture.

In the mid-sixties the bucket-and-spade British holiday was still in its heyday, with practically every family enjoying time at the beach at some point in July or August. One consequence of this was that seaside towns had a captive audience of millions of bored children. The British comics companies catered for them by printing Summer Specials of their titles, larger comics that often featured reprinted material or activities like colouring pages and stories involving the regular characters on holiday. Unsold stock was also retired to the seaside, ending its life fading on spinner racks and boxes in seafront shops. Moore would trawl through them hoping to uncover some unexpected treasure among the trash. It was on one such family holiday, in 1966, that he found the aforementioned collections of highlights from Mad, introducing him to ‘Superduperman’. He also came across an old hardback annual featuring the British superhero Young Marvelman, which he was less excited about, but he liked the cover and decided to buy it.

The name Marvelman enables us to make one of those connections that demonstrate how small the world of comics often is. The Captain Marvel strip was reprinted in the UK by publisher L. Miller and Co, and one consequence of the lawsuit parodied in ‘Superduperman’ was that Miller had to find new material once Fawcett ceased publication of Captain Marvel in the US. Their solution was to create an almost identical character. Captain Marvel had been a young boy, Billy Batson, who would say the magic word ‘Shazam!’ and be hit by a bolt of magic lightning that transformed him into an adult who had super strength and could fly. Artist Mick Anglo created a ‘new’ character, Marvelman, a young boy, Mickey Moran, who would say the magic word ‘Kimota!’ and be hit by a bolt of atomic lightning (‘kimota’ is, give or take, ‘atomic’ spelled backwards) that transformed him into … an adult who had super strength and could fly. Where Captain Marvel had a young sidekick called Captain Marvel Jnr, Marvelman had the sidekick Young Marvelman. Their adventures were published for nine years from 1954 to 1963 and amassed a total of 722 issues and 19 hardback annuals.

Even at twelve, Alan Moore knew Marvelman to be a rather cheap knock-off, but when he read the stories in the annual, he found them more charming than he had expected. His awareness of the history of the character sparked an idle thought: ‘I knew that Marvelman hadn’t been printed for about two or three years and that Marvelman had vanished … It occurred to me then “I wonder what Marvelman’s doing at the moment?” three years after his book got cancelled. The image I had in my head was of an older Mickey Moran trying to remember the magic word that would change him back to Marvelman.’ Like all good origin stories, the events of that day have been recounted numerous times over the years, and perhaps tidied up a little to make for a better tale. Moore gave the definitive account in an interview in 2010:

I remember I was reading these two very disparate books back in the caravan, and somehow there was a kind of a cross-fertilisation – well, it wasn’t even that much of a cross-fertilisation. I read the ‘Superduperman’ story, and thought, ‘Oh, I’d really like to do a story like that, that was so funny,’ and I thought, well, you couldn’t do it about Superman, because they’ve already done it. Could you do a story like that about this British superhero, Marvelman, that I was aware of? And so I just started to think about it – I think at the time I was even planning to submit it to the school magazine, which was the only publishing outlet that was available to me back then. It never got any further than just the idea, but I can remember that I thought it would be kind of funny to have Mickey Moran grown up and become an adult, who’d forgotten his magic word. And, yeah, at the time, that was seen as a satirical, humorous situation, but the idea just stayed in my mind, and over the next twenty or something years, fifteen years, it obviously percolated until it became my version of Marvelman.

Throughout his career, Moore has acknowledged ‘Superduperman’ as being a huge influence on his work, and the links to ‘Superduperman’ are often pretty concrete. As he implies in that interview, Moore would eventually write his Marvelman story (1982–9), and it culminates with, essentially, the battle from ‘Superduperman’ played straight: the hero does a vast amount of damage to the city he is meant to be protecting and finally defeats his equally powerful opponent only by tricking him; in addition, one of Moore’s last pitches to DC Comics was Twilight (1986), a series that, had it been made, would have featured an epic battle between Superman and Captain Marvel.

Moore’s most substantial debt to ‘Superduperman’, though, has nothing to do with specific characters or plot points. It relies on his own formulation of how the story fits into the history of comics, and the philosophy it encapsulates: ‘The way that Harvey Kurtzman used to make his superhero parodies so funny was to take a superhero and then apply sort of real world logic to a kind of inherently absurd superhero situation … It struck me that if you just turn the dial to the same degree in the other direction by applying real life logic to a superhero, you could make something that was very funny, but you could also, with a turn of the screw, make something that was quite startling, sort of dramatic and powerful.’ Moore has identified a desire to mimic the density of information in each panel of ‘Superduperman’ and its cynical take on heroism as the seed of Watchmen, but the idea he credits to Kurtzman of applying ‘real world logic’ is at the core of almost all of his early stories.

The family holiday over, the Moores returned home to their three-bedroom terraced council house at 17 St Andrew’s Road, in the Boroughs area of Northampton, opposite a large railway station (then Northampton Castle, later renamed Northampton). Alan lived with his parents Ernest, a labourer at a brewery, and Sylvia, who worked at a printer’s, his maternal grandmother, Clara Mallard, and younger brother Mike. The family had lived in the same house for thirty or forty years. Just before Alan was born, it had also accommodated uncle Les, aunt Queenie and their baby Jim (who slept in the wardrobe drawer), as well as another aunt, Hilda, her husband Ted and their children, John and Eileen. Life in such a crowded house had been tense although, as Moore noted at the time, he ‘was employed as a foetus and was thus spared the worst effects’.

The Boroughs – now Spring Boroughs – area of Northampton remains one of the most deprived areas of the United Kingdom. The town’s main industry had for centuries been boot and shoe manufacturing. The houses were a hundred years old, with outside toilets and no running hot water, although the Moores’ house was considered luxurious compared with many in the neighbourhood because the council had installed electric lighting. Ernest Moore earned around £780 a year, when the national average was about £1,330, and once told Alan that £15 a week wasn’t enough, and he hoped one day his son might earn £18. This was not abject poverty – the family may have used tin baths filled with water heated in a copper boiler, but that wasn’t so uncommon at the time, and they never went hungry. The Moores had a television when Alan was growing up, and every week he was given a little pocket money.

Alan was born in St Edmund’s Hospital on 18 November 1953, blind in his left eye. At first he had red hair, a family trait (there were people alive in 1953 who remembered his great-grandfather, Mad Ginger Vernon). He was baptised into the Church of England at the local church, St Peter’s, and with both his parents at work, he was raised by his grandmother, ‘a working class, Victorian matriarch. She was a deeply religious woman who never said very much but then didn’t need to because everybody obeyed her implicitly’. Moore doubts she ‘ever travelled more than five or ten miles from the place she was born’. (While his grandmother was devout, Moore did not have a religious upbringing, and has claimed he learned the basics of morality from reading Superman.)

In 1967, Jeremy Seabrook wrote The Unprivileged, the first book in a long career charting poverty throughout the world. It was an oral history of the working class of Northampton. The portrait he painted was of a community only a few generations away from agricultural peasantry, locked into old rituals of speech, family behaviour, deference to their social superiors and plain superstition: ‘The real fear in which their superstitions held them – and at least fifty common phenomena were considered certain forerunners of death – was a grim and joyless feature of their lives … Their irrational beliefs were like an hereditary poison, which, if it no longer manifests itself in blains and pustules on the surface of the skin, nonetheless continues its toxic effects insidiously and invisibly.’ This is echoed in Moore’s description of his grandmother, who had a ‘nightmarish array of sinister and unfathomable superstitions … she managed through sheer force of will to involve the entire household in her system of Juju and Counter-Juju. Knives crossed upon the dinner table, as an instance, heralded the forthcoming destruction of the house and its immediate neighbourhood by a rogue comet. To avert this peril, the catastrophically crossed cutlery had to be struck forcibly by yet a third knife.’ Seabrook concluded that attitudes like this left people insular and ill-equipped to deal with a world that was changing rapidly, that they were ‘exposed to an overwhelming sense of loss, seeing the certainties of a lifetime take on a bewildering and terrifying relativity … the life of the streets had a devitalising effect and did not allow of any departure from a rigidly fixed pattern of behaviour and relationships.’

The Unprivileged was a study of Seabrook’s own upbringing. He was born just a few streets away from the Moores’ house, fourteen years before Alan. He recalls:

As far as working-class Northampton of that time is concerned, it was definitely separated by districts – Far Cotton and Jimmy’s End were different from the Boroughs, which were, in any case, in the process of being demolished in the late fifties, early sixties. The boot and shoe industry was also being eclipsed – it was one of the earliest occupations that were victims of de-industrialisation. The most remarkable thing was the sameness of people’s lives – the almost regimented coming and going to work, the predictability of life – the pub, factory, maybe chapel, the pictures, the young people walking up and down Abington Street, the slightly louche places like Becket’s Park (clandestinely gay) and around the Criterion and Mitre (prostitution). The arrival of the bus from the American base in the market square on Saturday night was a weekly event.

In the mid-sixties, Seabrook was teaching at the local grammar school, where he was Alan Moore’s first-form French teacher the year before he wrote The Unprivileged. He doesn’t recall Moore specifically, but when he describes the prevailing character of the area, he uses at least some of the same words that have been used to describe Moore over the years: ‘The shoe people were generally narrow, suspicious, mean, self-reliant, pig-headed, but generally honourable and as good as their word.’

Moore could not have known as a boy that many of the early comic book writers and artists had grown up in an even more deprived place than fifties Northampton – the Depression-era New York slums. It would be some years before comics fans turned their attention to the history of the ‘Golden Age’ of the 1940s, and it’s perhaps only in the twenty-first century that studies of the period have gone beyond the anecdotal. But Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000), Gerard Jones’ book Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book (2005) and Michael Schumacher’s biography of Will Eisner, A Dreamer’s Life in Comics (2010) paint a consistent picture of the genesis of the industry and of the superhero genre, revealing a pattern of the young sons of immigrants exploited by companies formed and run using highly dubious business practices … often by other young sons of immigrants.

Much later, some of the Golden Age creators would write overtly autobiographical works, like Eisner’s A Contract With God (1978) and Life, In Pictures (2008). Although it was not always so obvious, their superhero work in the 1940s often drew from personal experience as well. Many comics were power fantasies about confronting bullies – from a crook on the corner to Hitler himself. Comics historian Mark Evanier, a friend and former assistant to artist Jack Kirby, has described Fantastic Four member The Thing as ‘an obvious Kirby self-caricature’. The Thing is a gruff and pugnacious brawler who was a member of the Yancy Street Gang as a kid. Jack Kirby had been a member of the Suffolk Street Gang, and had frequently fought running battles on the streets and rooftops of the Lower East Side in turf wars with the Norfolk Street Gang:

I had to draw the things I knew. In one fight scene, I recognised my uncle. I’d subconsciously drawn my uncle, and I didn’t know it until I took the page home. So I was drawing reality, and if you look through all my drawings, you’ll see reality.

Like all artists, the creators of comic books draw on what they know. The life stories of comic book writers and artists are often far darker, stranger and more troubled than those of their creations. There’s no contradiction here. Who is going to have the strongest urge to enjoy creating escapist fiction? Someone with a life they want to escape from.

Moore, however, has corrected interviewers seeking to portray his early life as particularly squalid, saying on one occasion ‘this is not a tale of extraordinary poverty by any means … I had a very happy childhood’ and explaining ‘I never really thought much about material luxury. That was kind of where I was starting from. My family never had anything. It was never as grim as it sounds because it was normal, in [the] context of what I was used to.’ This doesn’t mean he waxes lyrical about his background, either. While he remains committed to his roots, and sees much of value – far more than Seabrook does – in the culture found in the terraced streets of Northampton, now and then, there are, Moore concedes, ‘things I personally find very sad about the working class. You know, a lot of them are a bunch of racists, a bunch of idiots. They’re in these awful social traps that they can’t get out of. They blunder through life.’

Moore was reading by the time he was four or five, with his parents – who, unlike many of their neighbours, valued literacy – encouraging him at every turn. They read little themselves (his father occasionally read pulp novels and some anthropology, and Moore suggested once that the second thing he had ever seen his mother read was one of his Swamp Thing collections) but Alan quickly became omnivorous. He already had a taste for fantasy stories, and the first book he picked out when he joined the library at the age of five was called The Magic Island. He soaked up mythology and folklore.

‘I was looked after and cared for and all the other things that a child should be, but in terms of my inner life, or my intellectual life, I was largely left to my own devices. Which suited me just fine. I knew where the library was; I knew where I could find information if I wanted it.’ He was an imaginative, precocious child at Spring Lane, the primary school two or three minutes’ walk from his home. The school took in boys and girls from the streets around Moore’s house, and so he knew every one of his fellow students from his first day there. When he was about ten, he started drawing his own comics in a Woolworths jotter, branding them all as Omega Comics. He charged a penny a read of tales of The Crimebusters, Ray Gun (featuring a character with a ray gun whose secret identity was Raymond Gunn) and Jack O’Lantern and the Sprite. He said at the time it was to raise money for UNICEF, but later admitted it was mainly done in a failed attempt to impress a girl called Janet Bentley. Throughout his early school career he was something of a star pupil.

This was not an idyllic childhood. Moore has talked about how children would attack each other, often in ways that were genuinely dangerous. In one case ‘they hanged me from a tree branch by my wrists with string’; in another ‘they caved the underground den in on top of me’, leaving him ‘crawling like a lugworm through the smothering black dirt’. But, on the whole, Moore was happy. Tall for his age, he ‘thought I was a miniature god. They made me the head prefect at Spring Lane. I was the brainiest boy in the school and the world was my oyster.’

This idyll was abruptly ended when Moore sat his Eleven Plus.

The intention of the 1944 Butler Education Act had been to level the playing field for all schoolchildren. At the end of their primary education, around the age of eleven, every child sat an examination which measured skills in arithmetic, writing and problem solving. Those who passed – around a quarter of students who sat it – went to prestigious grammar schools for a full academic training; those who failed were consigned to secondary moderns and a more rudimentary preparation for working life. The lion’s share of the resources went to the grammar schools, so the secondary moderns, and those who attended them, quickly came to carry the stigma of failure. The theory was that the Eleven Plus was entirely meritocratic, a way to grant a free top-class education to all those who would benefit from it, regardless of background. The system was designed, in large part, to identify and reward intelligent working-class children. In practice, middle-class pupils had many advantages – their parents could, for example, afford to send them to preparatory schools specifically designed to get students through the exam. Some parts of the country had insufficient places for all the pupils who passed; this problem was particularly acute for girls.

The Eleven Plus, then, was crude and in many ways formalised the inequalities it was designed to eradicate, but it worked exactly as it was meant to for Alan Moore. He passed, and was sent to Northampton School for Boys, known locally just as ‘the boys’ grammar school’ (there was a girls’ grammar school nearby). It was on the other side of town, and took around 500 pupils from the whole of the local area. It was a shock to the system for Moore: ‘Call me naïve, but entering grammar school was the very first time I’d actually realised that middle-class people existed. Prior to that I’d thought that there were just my family and people like them, and the Queen. I had really not been aware that there was a whole stratum of society in between those two positions.’ According to Moore there were only ‘two or three’ other working-class boys at the school and he hardly knew anyone there.

Seabrook suggests that the system had a clear agenda for boys like Moore: ‘The grammar school was, for working-class boys, primarily a door to the middle class. Its unacknowledged curriculum was advanced snobbery and social climbing. It separated those who might, at another time, have been leaders of the working class, politicians or trade unionists, so in that sense, while it advantaged the individuals concerned, it could be said to have impoverished the communities. The school was modelled on public school to some degree, but many of the boys resisted the ethos, although perhaps not consciously.’ Seabrook had noted in The Unprivileged: ‘The public boast that “they make proper little gentlemen of ’em at the grammar school” often conceals shame and perplexity when the proper little gentlemen return home, impatient and critical of the way their parents live. They marvel at the remote and inaccessible places in which their children’s minds move, and as they leaf timidly through a book left on the kitchen table they wonder who this Go-eth can be and whether it is he who is responsible for their son’s alienation.’

There is no indication that Moore’s parents felt that way, but Moore himself certainly did. For the first time, he was embarrassed to take his friends home. He found the school’s all-male atmosphere uncomfortable and did not share any particular enthusiasm for sports. The emphasis on authority and rules simply didn’t suit his style of learning. ‘The school was an odd mixture of strange Dickensian customs and normal, everyday mid-sixties modernism. It was an unusual environment; it was a school I never liked. The Northampton Grammar School was impersonal and cold and incredibly dull and authoritarian.’

A more direct blow to Moore’s ego came at the end of the first term, when grades were assigned. He had plummeted from star pupil at primary school to nineteenth in a class of around thirty in the first term at grammar school. He was twenty-seventh in the class by the end of the next term. Some of this was down to his classmates benefitting from the advantages of a better primary education, already having been taught Latin and algebra, subjects Moore had never encountered. Some was a consequence of Moore having been a big fish in a small pond at Spring Lane: ‘I thought I was a genuine intellectual light. I hadn’t realised that actually, no, I was just about the smartest of a pretty crap bunch!’

Moore gave up academically. ‘I decided, pretty typically for me, that if I couldn’t win, then I wasn’t going to play. I was always one of those sulky children who sort of couldn’t stand to lose at Monopoly, Cluedo or anything. So I decided that I really wanted no more of the struggle for academic supremacy.’ This was not a case of Moore giving up on learning. Instead he became an autodidact, pursuing his own inner life, and he is clearly proud he ventured off the beaten path in his reading. Most of the books seem to have been fiction – he was particularly fond of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, he went through a Dennis Wheatley phase, a Ray Bradbury phase and an H.P. Lovecraft phase. He would soak up what he read, which was eclectic and idiosyncratic. Even at grammar school, he was reading at a slightly more advanced level than his peers, and occasionally found – for example with Mad or, later, Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds magazine – that he was reading things he was a little too young to fully appreciate.

Less than a handful of his fellow pupils shared his interest in comics, and he failed to impress anyone at the grammar school with his Omega strips, and soon stopped producing them. But Moore continued to read comics. By the late sixties, there was a new batch of Marvel titles like Silver Surfer, Nick Fury: Agent of SHIELD and Doctor Strange for slightly older readers, starring characters who were not quite straightforward superheroes in stories inflected a little towards introspection. The storytelling could now be more stylised and impressionistic, and there were innovations like silent sequences and psychedelic spreads. Moore noted, ‘Probably the most remarkable thing that Stan Lee achieved was the way in which he managed to hold on to his audience long after they had grown beyond the age range usually associated with comic book readers of that period. He did this by a constant application of change, modification and development. No comic book was allowed to remain static for long.’ These titles did not challenge the sales supremacy of Archie or DC’s Superman and Batman titles or become the dominant style of mainstream comics, but they found an avid audience among teenage readers who were starting to respond to the medium in a more sophisticated, knowing way. Comics fans were also beginning to talk to each other.

Alan Moore judges that British fandom began to ‘catch fire’ in 1966, a couple of years later than in America. While their American counterparts tended towards nostalgia, virtually everything was new to British fans, who celebrated the latest American imports alongside material from the forties and fifties that had not previously shown up in the UK, ‘so we applauded people like Jim Steranko, Neal Adams; people who were actually pushing the medium forward, trying to make it do things that it hadn’t done before. We went berserk when we discovered Eisner, through the Harvey Spirit reprints that were done in the mid-sixties. And EC Comics. But it wasn’t a nostalgia for Eisner or EC – these were things we were discovering for the first time.’

One of the most prominent of the British comics fans was Steve Moore. He is four years, five months older than Alan, and by the late sixties was working for Odhams, a publisher reprinting Marvel strips for the British market and replicating the Stan Lee formula so slavishly that he was referred to in editorials as ‘Sunny’ Steve Moore. Along with fellow editor Phil Clarke he also published two issues of what is thought to be the first British comics fanzine, Ka-Pow, and organised the earliest British comics conventions. Alan Moore was buying Odhams’ Fantastic, mainly for its only original strip, Johnny Future – written by Alf Wallace and drawn by Luis Bermejo – the adventures of a surviving missing link between modern human and Neanderthal who falls into a nuclear reactor to become a super-evolved being capable of great feats of strength and astral projection. And Alan didn’t just subscribe to Ka-Pow, he began corresponding with both Steve Moore and Phil Clarke.

Alan Moore and Steve Moore have been friends ever since, and, as we will see, Steve’s influence on Alan’s life cannot be overestimated. Alan has described him as ‘the most influential figure in my life in many ways, this was the guy who taught me how to write comics, got me into magic and is in many ways responsible for completely ruining my existence’. Steve Moore appears unassuming, particularly when standing next to his namesake, but Alan has worked hard to disabuse people of this notion, writing a short story, Unearthing, a candid biography that starts at the moment of his friend’s conception and encompasses the wide variety of weird encounters he has had. Steve Moore admits to being ‘bewildered by all the attention it’s getting … the whole thing has rather surprised my friends and relatives!’, possibly because Unearthing includes details of his erotic relationship with the moon goddess Selene.

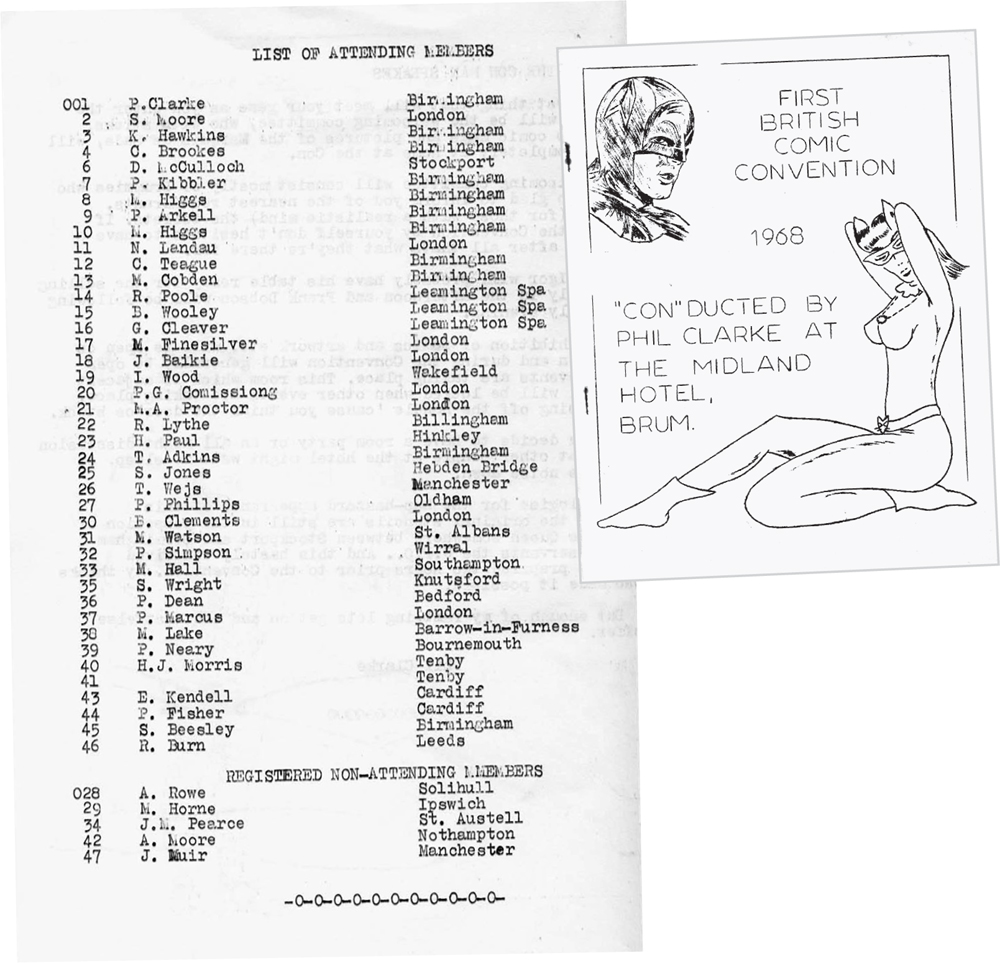

Alan Moore was a ‘supporting member’ of the first British comic convention, Comicon, at Birmingham’s Midland Hotel in August 1968. He did not attend (he was only fourteen), but helped it financially by buying a fundraising magazine, and his name appeared in the convention booklet alongside those of many people who would go on to work in the British comics industry, either creatively, in editorial or by running comics shops and distributors (see next page).

He was, however, present at the second Comicon, the following year at the Waverley Hotel in London: ‘There were sixty or seventy people there and that as far as we knew was the entire number of people who were remotely interested in comics in the British Isles.’ The convention was the first time that Alan and Steve Moore met, after a year or so as penpals. Alan also encountered Frank Bellamy, who’d drawn strips like Dan Dare and Fraser of Africa for the Eagle (the veteran artist was a little taken aback to learn that people discussed his work). The main guests were two British artists who had worked for Marvel in the US: Steve Parkhouse – who remembers their meeting: ‘I was struck by Alan’s demeanour. He was very, very young – but very, very funny. He was undeniably a performer’ – and Barry Windsor Smith, who the following year would start an acclaimed run on Conan the Barbarian (a comic avidly read by a young Barack Obama). Comicon became an annual event. At this and subsequent conventions, as well as through reading and contributing to fanzines, Alan Moore would come to know (if not always actually meet) many people a little older than him who were starting what would be long careers in the comics industry, and who would end up working with him in the eighties – people like Jim Baikie, Dez Skinn, Kevin O’Neill, David Lloyd, Brian Bolland and Dave Gibbons.

Moore’s fascination with America, and his avid reading of material like Mad, meant he became aware of the counterculture a number of years before it was given that name. He liked what he saw. When asked, ‘So would you say the sixties was a really important time for you in terms of your political development?’, Moore answered: ‘For me it was absolutely formative, if I hadn’t have been growing up during that time I certainly wouldn’t be the same person that I am today.’ Sixties culture, he said,

seemed to have blossomed from nowhere … it was a convergence of several different social trends, there was an awful lot of increase in technology that took place during the war; there was an economic boom after the war; there was a massive generation, the biggest human generation that has ever existed was born in the wake of the war; and all of these things came together in around about the early sixties, so there was this fairly unprecedented explosion of ideas and I think initially the counterculture, as we referred to it then, it was left-leaning but it was it was a very radical take upon even leftist ideas. It tended to reject all kind of authoritarianism and it was much more pleasure based, much more centred upon joy, ecstasy, it was very enlightened in my opinion.

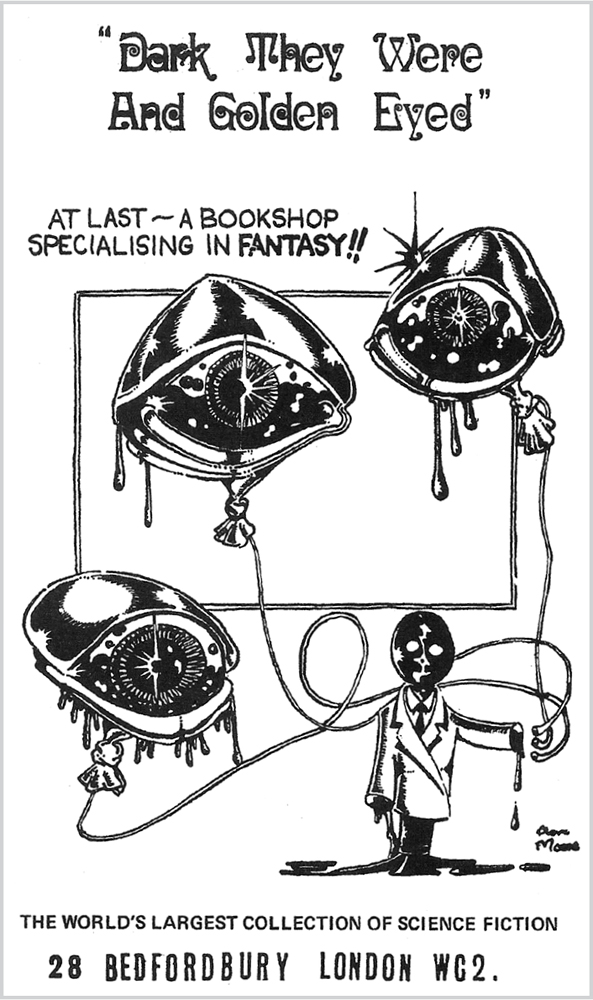

Alan was ‘relatively drug-free, fresh-faced and squeaky clean’ in 1969 when he first met Steve Moore, but there was a distinctly psychedelic tinge to the comics scene. ‘Most of those early English comic fans were hippies, or at least proto-hippies or would-be hippies. They were all hanging out at the only comic and science fiction shop in Britain, which was called Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed, named from a Ray Bradbury short story’s title.’ Alan’s first published work (outside school magazines) was an advert for the shop, an illustration that appeared in the September 1970 issue of the magazine Cyclops. He wasn’t paid.

Others attending Comicon went on to open comic shops and mailorder businesses. Many published fan magazines, usually fairly eclectic publications that included essays, short stories, illustrations and cartoons about whatever interested them. The print runs of these fanzines very rarely reached three figures: they were almost all made on mimeographs, small machines that used an electric spark to burn type into a wax stencil (hence the alternative name for the device, the electrostenciller). Most schools, churches and offices used them to produce newsletters or flyers. Once they were printed, the editor would collate and hand-staple the result.

Moore contributed to a number of titles. He ‘spent a hell of a long time gathering material’ for an essay about pulp character The Shadow for Seminar (1970). He made a couple of contributions to Weird Window: a book review, various illustrations of monsters and the poem ‘To the Humfo’ appeared in #1 (Summer 1969); #2 (March 1971) had an illustration of a Lovecraftian Deep One by Moore and a prose story, ‘Shrine of the Lizard’ (‘I’d just read Mervyn Peake’s excellent Gormenghast books at the time, so all the characters have names like Elly Blacklungs and Toziah Firebowels’). An eleven-word letter by Moore appeared in Orpheus #1 (March 1971) and he contributed to the horror fanzine Shadow.

Soon, though, he wanted to produce his own magazine. ‘Myself and a couple of other kids of my age, some from the grammar school that I attended, some from the girls’ schools, we decided spontaneously to put together a magazine of bad poetry basically. It was called Embryo, it was originally going to be called Androgyne, but I found that I couldn’t fit that lettering onto the cover so I shortened it. It was very ramshackle.’ Its covers were printed on coloured paper, and it sold for 5p, rising to 7p by #5. Moore produced covers, illustrations and poems for Embryo. ‘I was writing what I thought was poetry. Usually angst breast-beating things about the tragedy of nuclear war, but were actually about the tragedy of me not being able to find a girlfriend.’ While it was not a comics fanzine, the last issue featured a four-page comic strip written and drawn by Moore, ‘Once There Were Daemons’. Whatever Moore’s reservations about the quality of his verse, his work on Embryo brought him to the attention of a local poetry group, which he joined.

While Moore had been set back academically, he had never got into much trouble at school; he started smoking, and he would occasionally bunk off to ride a friend’s motorbike around the grounds of the local psychiatric hospital. His parents knew he was different, but found this easy to accept:

I was regarded almost from the outset as unusual, but this was within a family tradition where unusual people were not actually that unusual. There had been previous people in the family line, mostly on my father’s side, who were quirky, talented and in certain instances certifiable. Generally my parents seemed to be very impressed that I could draw a picture and string words together, sometimes in rhyme, in a way that they did not feel competent to … My family accepted me as, in my mum’s phrase, ‘a funny wonder’. This was an all-embracing phrase that incorporated an awful lot of things. It was something that was wonderful, but funny in the peculiar sense. Such people were not unknown in the bloodline. ‘Oh, we get one of these every hundred years or so.’ I always had an odd relationship with my family, because turning out to be someone like me did sometimes bring problems with it. It sometimes changes things, luckily with my close family I don’t think it did.

The most serious trouble he had got into was when he published a poem in Embryo #1, written by his friend Ian Fleming, that used the word ‘motherfuckers’. Moore was hauled over the coals by the headmaster, H.J.C. Oliver, and promised to apologise in the next issue. Instead he handed over the editorial to Fleming, allowing a repeat of his offence:

Also, in passing, a few words about some people’s objections to the use of certain streetwords in certain poems. (It’s a pity that all the ‘NAUGHTY’ poems were by the same naughty author.) All, except in one case, (‘Motherfuckers’, in ‘When they see us coming’, which was used partly to complete the poem’s contrasts, & partly because the word’s meaning(s) were used in context with the rest of the poem) were used, not to shock anyone, not to give anyone a cheap thrill, not deliberately, but simply because they were written down as part of the poem, as the poem was formulated, i.e. they were in perfect context.

THE REAL OBSCENITY GOES ON ALL AROUND US, UNDER MANY DIFFERENT NAMES.

(nice rhetoric, man, nice …)

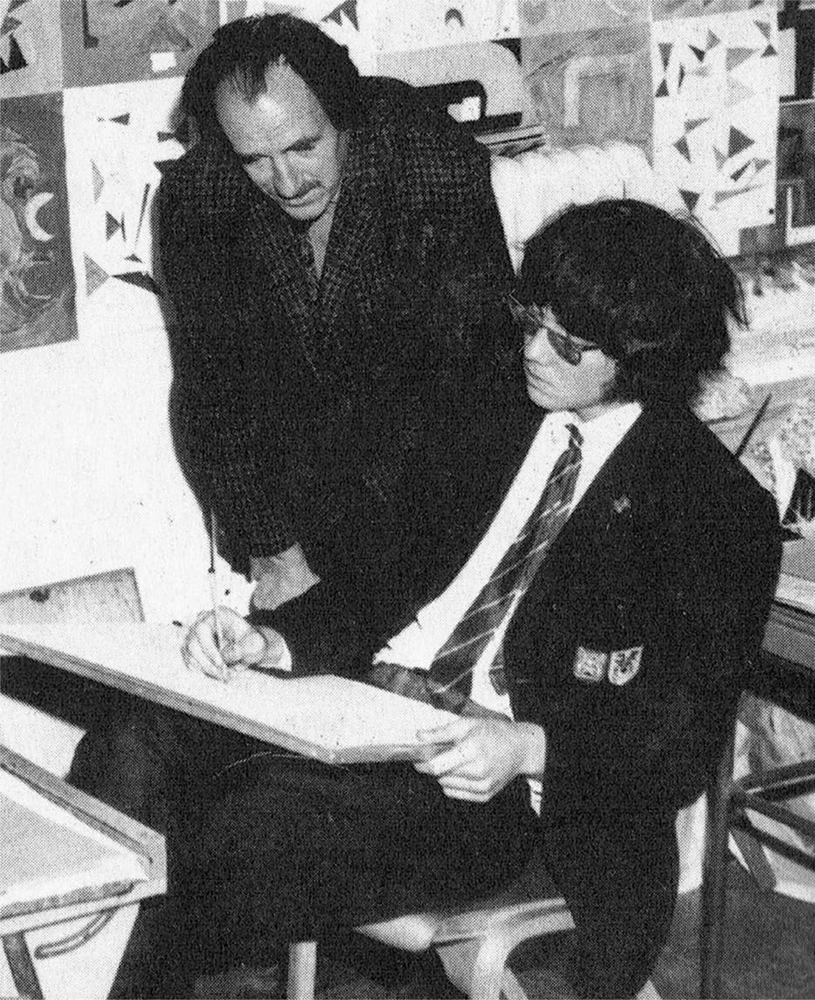

Embryo was banned, which only increased its notoriety and sales. Despite this, Moore remained in good enough standing with the school that when he was seventeen and the art department was featured in the local paper, he was the pupil chosen to appear in the photo. Moore had begun growing his hair, but it was shaggy at this stage, rather than shoulder-length. It seems clear that the school and Moore had found ways to cope with him being an artistically minded round peg in a square hole.

It was a second grand egalitarian social engineering project that would devastate Alan Moore and his family, starting in 1965 when Northampton – first settled in the Neolithic – was designated as a New Town.

Britain faced a housing crisis. Millions of Britons still lived in Victorian conditions – their houses were a hundred years old and many were now badly dilapidated. The Second World War had seen the Luftwaffe damage or destroy much of the housing stock, particularly in the cities; after the war, there had been a population boom. The British government set plans in motion to create large towns laid out with cars in mind, and with modern industrial plants, to ease pressure on the largest cities. This construction would be overseen by powerful development corporations. Northampton was part of the ‘third wave’ of such towns along with Central Lancashire, Milton Keynes, Peterborough, Telford and Warrington. Northampton is about sixty-five miles from central London, so was only about an hour away – in theory at least – by rail or via the brand new M1 motorway. The new arrivals were mainly from London, and tended to be young, aspirational working-class families.

In some cases, like Milton Keynes, the New Towns were essentially entirely new settlements (they were built on the sites of tiny villages). Northampton, however, had an existing population of 100,000 in 1961. That would rise to 130,000 in 1971, with the target of a population of 230,000 by 1981. New Town status brought a great deal of government money, some of which would be used to replace the Victorian slums now considered unfit for human habitation, and on 3 July 1967, Northampton County Borough Council passed the first of a series of resolutions that designated parts of Northampton as ‘clearance areas’. The Northampton Development Corporation began operating in 1968, opening new tower blocks in the Eastern District in 1970 and buying up private property with compulsory purchase orders. Most residents, though, were council tenants and simply received a letter saying they were to be relocated. Whole streets were bulldozed.

The Unprivileged ends with a striking image of the abandoned terraced streets; the people had gone, but left what possessions they had behind, including furniture, family photographs and even a bird in its cage. For countless people in Britain, this was a time of great social mobility and unparalleled opportunity, but according to Seabrook such euphoria did not last long:

The great clearances of the fifties and sixties were like migrations – people couldn’t get out quick enough; you can’t blame them, because the conditions into which they were moving were so much better – it is only when all the new things fell apart in their hands that people began to think twice about the meaning of change. There was in the seventies a plan for a ring road in Northampton that would have demolished hundreds of houses which people were proud of, as their ‘little palaces’ – slum clearance struck at people’s contentment with their lot. Redevelopment principally served the building, concrete and steel industries before it served the people who were being moved.

For the Moores, it was a catastrophic disruption. When he was seventeen, Alan Moore’s family was relocated to Abington, formerly a prosperous part of Northampton. His eighty-four-year-old grandmother Clara died within six months. The council moved Moore’s other grandmother, Minnie, from the house in Green Street where she had lived all her life to an old people’s home and she died within three months. Moore has no doubt what caused their deaths: ‘Being moved from the place where you got your roots was enough to kill most of those people … the place where I’d grown up was more or less completely destroyed. It wasn’t that they put anything better there; it was just that they were able to make more money out of it without all those bothersome people.’

Alan Moore was expelled from Northampton School for Boys two weeks after the death of his grandmother Clara. When asked about this in 1990, Moore would only say it was ‘for various reasons’; subsequently, one interviewer reported the offence had been ‘wearing a green woolly hat to school’, a remark Moore doesn’t remember making and suspects ‘might have been a facetious remark or it may even have been misheard, I’m not sure’. He first revealed the truth in The Birth Caul (1995): he was expelled for dealing acid. By the time he spoke to the BBC in 2008, though, it had become an anecdote for Moore the raconteur: ‘At the age of 17 I became one of the world’s most inept LSD dealers. The problem with being an LSD dealer, if you’re sampling your own product, is your view of reality will probably become horribly distorted … And you may believe you have supernatural powers and you are completely immune to any form of retaliation and prosecution, which is not the case.’ The Observer later reported that he had been taken to the headmaster’s office and confronted by a detective constable from the local drugs squad. Moore wasn’t charged or fined: ‘The expulsion was technically groundless. I was searched, but there was absolutely nothing on me and the only thing that they had was the hearsay evidence of a number of my schoolfriends who had named me – we were young then and easily intimidated by the police – and that wasn’t conclusive proof. I was expelled from school, but there were no charges brought. I have a clean record.’

Moore’s initial reluctance to spell out why he was expelled was out of respect for his parents. It was only after their deaths that he started referring to his drug dealing in interviews. At the time, he had initially told them he’d been framed, but when he later admitted the truth, they were (unsurprisingly) very upset and disappointed. As Moore would say in 1987, ‘it must be terribly difficult being my parents’.

Given Moore’s countercultural leanings, it would have been odder if he hadn’t tried LSD. Moore glosses his taking acid at the time as ‘purely for ideological reasons, believe it or not’, based on reading Timothy Leary’s essay The Politics of Ecstasy, which argued that people taking LSD were visionaries like the shamans of tradition, tasked with leading others out of the darkness. By this point, Leary was advocating the case that psychedelic experiences unlocked the next stage of human evolution, and so logically the more people who had LSD trips, the more likely it was that society could become more peaceful, harmonious and generous.

Moore had first tried the drug on 12 September 1970, a couple of months before his seventeenth birthday, at a free open-air concert in Hyde Park. It was a wet Saturday afternoon, but the music was pure Californian psychedelic rock. Stoneground opened, followed by Lambert and Nutteycombe, Michael Chapman, General Wastemoreland, and Wavy Gravy. John Sebastian played ‘Johnny B Goode’. Even The Animals, originally from Newcastle upon Tyne, had by this time moved to San Francisco – lead singer Eric Burdon celebrated his return to the UK by splitting his trousers during a performance of ‘Paint It Black’. Blues-rock band Canned Heat were the headliners. Moore bought some large purple pills from ‘some kind of shifty-looking dope dealer straight out of a Gilbert Shelton cartoon’ and had his first acid trip to the soundtrack of ‘Future Blues’, ‘Let’s Work Together’ and ‘Refried Hockey Boogie’. In the year between this event and his expulsion, Moore went on more than fifty acid trips – ‘LSD was an incredible experience. Not that I’m recommending it for anybody else, but it hammered home to me that reality was not a fixed thing.’

Taking LSD may have given Moore insight into new realms of the imagination, but it was also directly responsible for dumping him out of school in the winter of 1971. He faced the problem that while his consciousness may have expanded, ‘I found that my horizons had rapidly contracted. The headmaster who had dealt with my expulsion had, I think, taken me rather personally. He had written to all of the colleges and schools that I might have thought of applying to and told them that they should under no circumstances accept me as a pupil, because this would be a corrupting influence upon the morals of the other students. I believe that he did at one point in the letter refer to me as “sociopathic”, which I do think was rather harsh.’ Moore has, however, elsewhere described his younger self using exactly that word: ‘I did decide to get revenge. I decided that there would be some way in which I could get my own back for this upon everybody that had annoyed me. I was a monster! … Very antisocial. Sociopathic.’ He concluded that those in authority were out to get him – an idea that’s stuck with him throughout his life.

Moore continued to live with his parents on Norman Road in Abington. He soon discovered that having ‘the antimatter equivalent of references’ meant he would not be going to Northampton Arts School, though he did make one attempt to get a job where his artistic skills would be appreciated:

I noticed that there was an advert for ‘cartoonist wanted’, somebody to draw advertising … and they asked as a trial ‘give us something that would work for a pet shop’ and I did this – in retrospect – quite scary dog, and I’d used Letratone on it to show that I was au fait with sophisticated shading techniques. It was rejected of course. What they actually wanted was a smiley picture of a puppy, which I could have done, but I’d thought they wanted to see what a brilliant artist I am. No, they actually wanted to see you could follow a brief intelligently, which I was incapable of doing. So, with that, I gave up. That’s when I decided to go down to the labour exchange and take whatever was available.

Moore understood what he was in for: his father, grandfather and great-grandfather had all been labourers. The first job he took was in the Co-op skinning yard on Bedford Road. He was paid £6 a week to cut up sheep that had been soaking overnight in vats of water and their own bodily fluids. It was a place ‘where men with hands bright blue from caustic dye trade nigger jokes’. He was there for two months before being sacked for smoking cannabis in the tea room. He then worked as a cleaner in the fifty-seven-bedroom Grand Hotel on Gold Street (now the Travelodge Northampton Central), and later he worked in a W.H. Smith’s warehouse packing books, magazines and, of course, comics.

When asked about these early jobs, Moore has made the same joke on more than one occasion: ‘I tend to think of it as a long downward progression that ends as a comics writer.’