‘When you’re at that stage of your career there is a sort of a terror that becomes associated with actually sending your first piece of work in because I think that the reasoning that’s going through your head – if you can call it reasoning – is that if I send this in and it gets rejected, I won’t even have the dream that I could’ve been a great writer or artist. Better to never send it in and never have that rejection so I’ll always have the dream.’

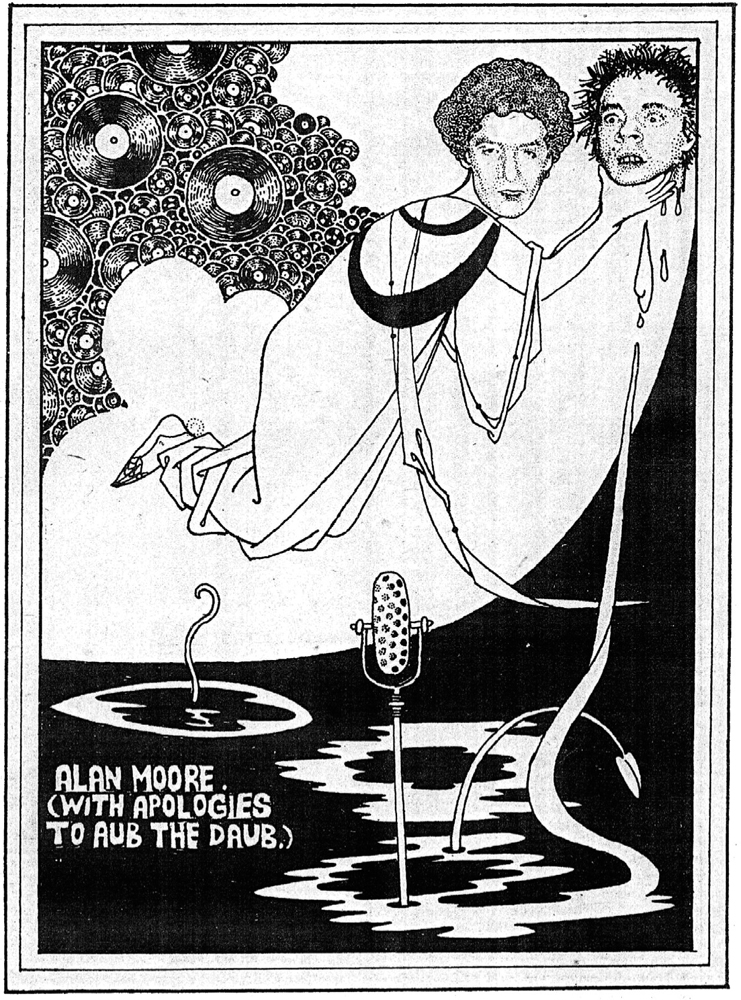

Alan Moore, Vworp Vworp #3 (2013)

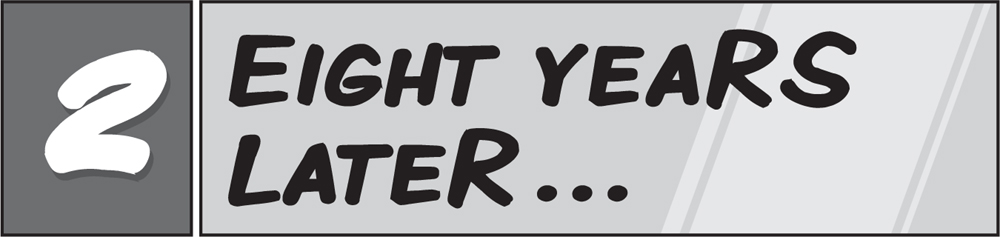

The end of Moore’s 2011 book The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century 1969 skips from the aftermath of a sunny, psychedelic pop festival to an epilogue set ‘eight years later’ in a black-and-white basement punk club. It’s a transition that sums up Moore’s feelings towards and experience of the seventies, a decade that started at the peak of the countercultural idealism that is close to his heart but ended with wholesale rejection and open hostility towards it. The time jump also matches a relatively uncharted period of Moore’s life. Having been expelled from school and consigned to the first in a series of menial jobs, in late 1971, his professional creative career began only with the publication of two illustrations for the New Musical Express in October and November 1978, and his first published work in mainstream comics did not appear until the summer of 1980, in Doctor Who Weekly and 2000AD. He’s summed up what happened in between by saying, ‘My occupation from the time I left school was in a series of thoroughly miserable jobs that I wasn’t interested in at all … I hadn’t got any ambitions other than a vague ambition to make my living by writing or drawing or by something which I enjoyed doing. Since those sorts of jobs weren’t on offer I didn’t really have any clear idea of how to go about getting one, or even if I was good enough to get one.’ His published work in the period adds up to less than two dozen pages of material for local zines and community magazines, none of which were paying jobs.

After Moore was expelled from school, almost all of his friends cut ties with him. He puts this down to their squeamishness over the jobs he was forced to take, but it’s clear that the long-haired, sullen eighteen year old who was ‘not quite in my right mind, and believed I had supernatural powers’ was a very different creature from the shaggy, drug-free sixteen-year-old Moore. Many in his circle of friends took drugs, but those who stayed on at school must have been inclined to see Alan as an example of the terrible fate awaiting them if they didn’t hunker down to work on their A-levels.

Moore did however have an oasis of continuity: the Northampton Arts Lab. About a year earlier, he had been a member of a poetry group that teamed up with the Arts Lab to run an event at the Racehorse Inn (it took place on 16 December 1970 and was advertised in Embryo #2). Soon after that, the group had merged with the Arts Lab, and from #3 (February 1971) onwards, Embryo was billed as a Northampton Arts Lab publication. This would grant Moore a social life and an outlet for his creative energies over the next few years. As he said, ‘the Arts Lab was what I was living for to a degree … because, all right, I was kind of trapped in terribly miserable circumstances with no obvious way out. In the evenings I could write something that I was pleased with and then a couple of weeks later there’d be a poetry reading – I could go along and read it; maybe do some work with some musicians reading the poems to music … And that felt like that was taking me somewhere.’

Arts Labs had sprung up across the country, following the lead of Jim Haynes, co-founder of the hippie magazine International Times. Haynes had known John Lennon and Yoko Ono before they knew each other, as well as Germaine Greer and a very young David Bowie. In September 1967, he reopened an old cinema on Drury Lane as a rehearsal room, exhibition space and hangout. The venue had quickly become a hub for London’s counterculture, and by 1969 there were more than fifty Arts Labs in towns around England. Each had its own flavour – the Brighton Combination, led by the playwright Noel Greig, for example, produced work that concentrated on gay liberation themes – but outside the Drury Lane original, the real powerhouse was Birmingham, which put on concerts of classical and rock music, made films and ran an arthouse cinema, as well as publishing numerous magazines and posters. Alumni of the Birmingham Arts Lab would go on to be early players in the punk music scene, as well as key figures in alternative comedy. They also boasted a particularly strong line of comics artists and cartoonists, including the vicious political cartoonist Steve Bell, the less vicious Suzy Varty, British underground comix mainstay Hunt Emerson and the graphic novelists Bryan Talbot and Kevin O’Neill.

In September 1969, fresh from a top-five hit with ‘Space Oddity’, David Bowie told the magazine Melody Maker:

I run an Arts Lab which is my chief occupation. It’s in Beckenham and I think it’s the best in the country. There isn’t one pseud involved. All the people are real – like labourers or bank clerks. It started out as a folk club. Arts Labs generally have such a bad reputation as pseud places. There’s a lot of talent in the green belt and there is a load of tripe in Drury Lane. I think the Arts Lab movement is extremely important and should take over from the youth club concept as a social service … We started our Lab a few months ago with poets and artists who just came along. It’s got bigger and bigger and now we have our own light show and sculptures, etc. And I never knew there were so many sitar players in Beckenham.

It’s a quote that sums up a lot of the appeal and philosophy of the movement. Music journalist Dave Thompson, who has written books about Bowie including Moonage Daydream and Hello Spaceboy: The Rebirth of David Bowie, says:

The beauty of the Arts Labs was that they truly were open to all, a precursor in many ways to punk rock – or the equivalent of an open mic night in Los Angeles, except they encompassed all the arts, and not just music. The guiding principle was that all art was valid; the organisers, at least, regarded the ‘doing’ to be of far greater value than the actual accomplishment. There was no ‘quality control’ button – if someone claimed to be an artist, a performer, a sculptor, an orator, then that was what they were, and some phenomenal talents emerged from the scene …

A lot of Arts Labs were in pubs (Bowie’s was at the Three Tuns), often utilising the same space that was a folk club a few years earlier; a blues club before that; and would become a disco a few years hence. Others used church halls, scout huts, any place where a decent space was available for a once-a-week rental, and a stage of some sort could be erected.

Being part of an Arts Lab was a social activity as much as it was about producing finished work. It encouraged people to be jacks of all trades, rather than concentrating on just painting or poetry or playing an instrument. Or, as Alan Moore put it, the ‘ethos of the Arts Lab was that you could do whatever you wanted, that you didn’t have to limit yourself to one particular medium, that you could jump about, you could blend media together and come up with new hybrids. This was of course all mixed in with the general soup of sensations that was the 1960s.’ There was no formal network of Arts Labs or central leadership. The only things linking them were a newsletter that went to every group and the occasional conference. Some Arts Labs managed to get funding from local government, and applied for grants from the Arts Council, but most were self-funding.

The Northampton Arts Lab was small and particularly ramshackle, consisting at its height of no more than a couple of dozen people, with more men than women. They met every Tuesday evening at 8 p.m. in a hired room at the Becket and Sargeant Youth Centre, and put on poetry readings, light shows and dramatic performances at various other venues. They produced roughly bi-monthly magazines, Rovel and Clit Bits, which were electrostencilled, hand-stapled, and looked a lot like Embryo, the zine Moore put together himself at school. Moore was part of the Northampton Arts Lab for two or three years and – as well as producing three issues of Embryo under its aegis – contributed at least one illustration and two-page comic strip to the third issue of Rovel. He did learn some of his craft at the Arts Lab: ‘That was where I first started writing songs, or song lyrics at least, working with musicians, which gives you a certain sense of the dynamic of words that you don’t get from any other field of endeavour. It was where I started writing short sketches and plays, which, again, is very, very useful. It teaches you about the dynamics of setting scenes up, resolutions, stuff like that. All of these things – poetry teaches you something about words and narrative; performing plays: creating different characters, different voices; writing songs … although they seem miles away from comics, all of them taught me things that have been incredibly useful since, even though I didn’t know it at the time.’ He concedes that ‘none of the art we were producing was wonderful, and so I can’t say that I learned at the feet of any great masters. What it did teach me was a certain attitude to art, an attitude that was not precious, that held that art was something you put together in fifteen minutes before you went on stage and performed it … it was messy – no lasting work of art emerged from it. What did emerge from that period was a certain set of aspirations, feelings, an idea of possibilities more than anything.’ It was also a forum that stressed performance – Moore couldn’t just write a poem, he was encouraged to recite it. He found he had a particular talent: ‘If you’d have seen me back then, you might have thought I was good at reading poems, I could engage an audience, I was a decent performer. I’m not saying the poems themselves were any good, but I was increasingly aware of what an audience responded to.’

The Arts Lab also provided a venue for existing artists. Moore was particularly impressed by the Principal Edwards Magic Theatre, a dozen-strong group who lived in a commune in Kettering, just up the road from Northampton. He saw them as ‘a model of the sort of thing that I wanted to do’, and what they were doing was described by the Observer in 1970:

A group of young people, mostly from Exeter University, are at present touring the country giving what they call mixed-media entertainment under the name of Principal Edwards Magic Theatre. They perform songs, dance, present light shows, intone semi-mystical poetry and enact masques. There are 14 members in all and they have just released an LP of some of their music, called, appropriately, Soundtrack.

But perhaps the main benefit Moore got from the Arts Lab was that he acquired a new group of friends, people like Richard Ashby, ‘one of my all-time heroes … Rich would overcome his own lack of talent in certain areas by thinking up some way to get around the difficulty, and it would usually be simple, ingenious, elegant. He had a mind which I really admired; he had an approach to art which I really admired. That was an influence that stayed with me every bit as much as the influence of people like William Burroughs, Brian Eno or Thomas Pynchon.’

Moore, Ashby and their friends wore their hair long, and they smoked dope on camping trips to Salisbury Plain, Scotland and Amsterdam. Arriving in Holland, on his first trip abroad when he was eighteen or nineteen, Moore was told by a Dutch customs official that his long hair made him look like a girl. So he began growing a beard.

It was through the Arts Lab that Moore met the Northampton-based folk musician Tom Hall, who took him under his wing. The two would remain friends (and occasional artistic collaborators) until Hall’s death in 2003. Hall was the first full-time professional artist Moore got to know. He remembers Mick Bunting, a leading member of the Arts Lab, saying once, ‘“If Tom Hall can’t live by his music he can’t live.” Which was the first time I’d actually heard that spelled out. I remember thinking that was awesome. That that’s what I wanted to be: somebody who could be completely themselves, who did not have a master or boss and who subsisted entirely upon the fruits of their own creativity. Tom was a real formative idol.’

But the countercultural movement had already peaked. California and London had moved on, and while the provinces lagged a little behind, the Northampton Arts Lab fizzled out around August or September 1972. As Moore explains, ‘The reasons are very similar to those that caused the demise of similar groups everywhere – lack of money, public support at gigs, really good usable premises and equipment, and the general frustration of not getting very far, all of which caused general disillusionment. After around four years the people involved no longer seemed to feel the need for “organised” group activities any more. Many felt they could work better on their own, or with a few friends than in a “big” group; others just seemed fed up.’

Within six months, a successor organisation had formed: the Northampton Arts Group, which was active for around eighteen months from spring 1973. This was a loose association of about twenty people, many of whom had previously been published in Embryo or Rovel. Moore has said he only had ‘some involvement’ with the Arts Group, and he appears on one list among those who ‘on occasions we’re helped by’, rather than as a member of the group, but in terms of finished results, it was more fruitful for him than the Arts Lab had been. The group published three electrostencilled zines in 1973 – Myrmidon, Whispers in Bedlam and The Northampton Arts Group Magazine #3 – and Moore drew the covers for all of them, as well as contributing pieces like ‘The Electric Pilgrim Zone Two’ and ‘Letter to Lavender’ and internal illustrations. He was an ‘inevitable’ presence at poetry readings, performing ‘ever popular’ pieces like ‘Lester the Geek’ and ‘Hymn to Mekon’. Neither of those was ever published, but a couple of Moore’s Arts Group pieces would go on to have convoluted afterlives.

Moore’s cover for the third magazine, which he titled ‘Lounge Lizards’, stuck with him. He first used it as the basis of his pitch when he entered a talent competition run by the comics company DC Thomson: ‘My idea concerned a freakish terrorist in white-face make-up who traded under the name of the Doll and waged war upon a totalitarian state sometime in the late 1980s. DC Thomson decided a transsexual terrorist wasn’t quite what they were looking for … Thus faced with rejection, I did what any serious artist would do. I gave up.’ Nearly ten years later, however, elements of this idea would provide some inspiration for V for Vendetta, and a quarter of a century on, the Doll showed up as the Painted Doll, a major villain in Moore’s series Promethea (1999–2005).

Moore also wrote a performance piece, ‘Old Gangsters Never Die’, which would resurface in a number of places in different forms over the years. He has joked that as it was a spoken monologue set to music about gangsters, he therefore invented gangsta rap. He was proud of the piece: ‘The language in that, and the rhythms, that was the pinnacle of my style of writing at that time and I’d written it to perform. I realised it had great emotional effect, it had a got a lot of punch, especially with a little bit of music in the background. I also realised it didn’t mean anything, other than evoking this rich material about gangsters. It didn’t say anything. I started to think the best thing to do would be stuff with the same command of language, but if it means something as well, I might get somewhere.’

As with the Arts Lab, a legacy of the Arts Group was that Moore formed a number of long friendships and industry contacts. These included Jamie Delano, who would follow him into a successful career in British and American comics; Alex Green, who would go on to be the saxophonist for a number of bands, including Army; and Michael Chown, known by the nickname Pickle, with the stage name Mr Liquorice, who Moore would later describe as a ‘new wave composer, entrepreneur, and Adolf Hitler lookalike’.

And it was on the way home from an Arts Group poetry reading in late 1973 – they were both taking a shortcut through a graveyard – that Moore met Phyllis Dixon. Another Northampton native, Phyllis was small and slim, a honey blonde. The two soon moved into a small flat in Queens Park Parade together. Within six months they were married, had moved to a bigger flat on Colwyn Road and had acquired a cat called Tonto. By this point, Moore had an office job at Kelly Brothers, a subcontractor for the Gas Board.

The Arts Lab movement had proved short lived, and virtually all of them had vanished by 1975. The only exception was the Birmingham Arts Lab, which survived until 1982, most likely because it owned its own premises, had always been run with relative professionalism and had secured Arts Council funding. Moore put the end of the movement down to the zeitgeist: ‘The tone of the times was changing, that sort of very spontaneous approach to art was something that could only have happened in the late sixties and didn’t survive very long into the early seventies. The economic climate was changing, people were changing.’ Moore was acutely aware that the sixties were over. The broad utopian vision that global consciousness was expanding and the Age of Aquarius was dawning had been scaled back to a few people living in communes and advocating ecological positions like self-sufficiency. Countercultural and ‘underground’ art styles became subsumed into the cultural mainstream. The Beckenham Arts Group might have ended, but David Bowie had the consolation prize of seeing Ziggy Stardust go platinum.

Maggie Gray has noted that ‘the prevalent narrative of this period … asserts an absolute and definitive split between contradictory but previously co-existent sections of the counterculture, usually categorised as its cultural and political wings’. The movement appeared to split into two factions: those who sought radical social change through political activism, and those had come to see the counterculture purely as a mode of art and music. In 1975, Moore found what looked like the perfect vehicle to square that circle. This was the Alternative Newspaper of Northampton, which started as a newsletter concerned with grass-roots politics, particularly charting the problems caused by the rapid expansion of the town. Issue #2 boasted of ‘Featuring trade unions, household fuel, welfare rights, citizens’ advice, arts, community information, education, housing’. Moore’s own experiences made him highly sympathetic to ANoN’s aims and he took up political cartooning; in the event, though, this effort wasn’t entirely successful. He diagnoses the problem as the venue: ‘ANoN was a very tame, very very tame, local alternative newspaper who asked me to do a comic strip for them. I did the rather anodyne Anon E. Mouse, which is not one of the high points of my career, but even that was apparently too inflammatory for the sensibilities of the editors and so I withdrew the strip.’

The sum total of Anon E. Mouse is five four-panel strips, published in ANoN #1–5, December 1974 to May 1975.

The first strip consists of four almost identical panels in which Anon E. Mouse and Manfred Mole are depicted sitting at a bar bemoaning the fact that people only sit around, they never do anything. The second (reproduced here) starts with Anon E. Mouse ‘laying it on the line with the Reverend Cottonmouth’. In the third, Anon E. Mouse rejects the idea of being a movie star after seeing a washed-up Mickey Mouse, while the fourth has Anon E. Mouse and Manfred falling out on the day of the revolution over the colour of the flag they’ll be flying on the barricades. The fifth is based around a pun – cartoonist Kenyon the Coyote tells Anon E. Mouse that he’s going to try ‘biting humour’; ‘if you don’t humour me, I’ll bite your throat out’. And that is it.

There’s nothing specific to Northampton or particularly topical, but perhaps most damning – and far harder to pin on editorial policy – Moore does nothing very interesting with the medium. The art is stiff. The ‘repeated image’ of the first strip exposes just how inconsistent the drawings are. Most panels are straightforward talking heads and all five strips are simple conversations between two characters. There’s no visual invention or much in the way of background detail. It’s early work, and there’s very little of it, but Anon E. Mouse is not a good place to look for glimmers of Alan Moore’s nascent genius.

Around this time, perhaps at least partially out of frustration with ANoN, Moore began planning his own magazine. Having decided on a title, Dodgem Logic, he wrote a letter with a list of interview questions to Brian Eno, and received a very thoughtful ten-page set of answers. Moore has remained an aficionado and it’s not hard to see why. Eno thinks very hard about a supposedly ephemeral art form like pop music, he’s concerned about the purpose of art, about the process of making it, and his work is often collaborative. His influences are science fiction and surreal comedy as much as they are other musicians. In his own words, however, Moore was not ‘together enough’ to complete an issue of the magazine, and spent a great deal of time doing little more than drawing the cover. Thirty years later, given the chance to interview whoever he liked for an episode of BBC Radio 4’s Chain Reaction, Moore chose Eno, and took the opportunity to apologise that his earlier attempt never saw print.

In 1976, Moore collaborated on a musical play that must count as his first major completed work: ‘Another Suburban Romance was a surrealist drama, I’m not even sure what it was about, or if it was even about anything. It involved a number of characters that were moving through this series of scenarios that involved meditations upon politics, sex, death and all of the other big issues.’ Among Moore’s contributions were three songs: ‘Judy Switched Off the TV’, ‘Old Gangsters Never Die’ (which, as noted, he had written about three years before) and the finale, ‘Another Suburban Romance’. (A surviving copy of the script – which was made on Moore’s typewriter – has handwritten annotations by him indicating where musical cues should go.)

While a 29-page script was completed, the piece was never performed in full, and it remains unpublished (although the songs were visualised as comic strips, without reference to the original play, by Avatar in 2003). Alex Green, one of the participants, says it was ‘a cross between Beckett and Peyton Place, had been written by Alan and Jamie Delano and was then in rehearsal. Glyn Bush and Pickle wrote an incredibly complex score which was exhaustingly perfected and mostly recorded only for the project to founder when a couple of actors dropped out.’

Another Suburban Romance has four scenes, and five characters: Kid, Gangster, Whore, Politico and Death. It was designed to be performed to an elaborate taped backing track, with a number of ambitious lighting effects, and features several long monologues and pieces of beat poetry. Scene One opens in a coffee bar where Kid is lamenting how bored he is when Gangster arrives, and – after he gives a rendition of ‘Judy Switched Off the TV’ – tells Kid he is looking for the mirror Bela Lugosi was using when he died cutting himself shaving. Gangster then performs ‘Old Gangsters Never Die’. Kid decides to track down Whore, who might know where the mirror is.

Scene Two starts with an elaborate mimed routine in which Whore accosts Politico, then Gangster and finally Death. She performs a monologue that starts ‘Torn stockings, crumpled silk, lipstick and Benzedrine’ then Kid catches up with her. After comparing hard luck stories, they are joined by Gangster and decide to visit Politico. At the opening of Scene Three, Politico is giving a long right-wing diatribe, before Kid enters. Politico is annoyed by Kid and doesn’t know anything about Lugosi’s mirror, but becomes excited at the thought it might be valuable. Gangster now enters, and reports that he has killed a number of Politico’s enemies, as ordered.

Scene Four begins with a long diary entry from Death. The arrival of Kid and Whore interrupts him, and Death goes on to explain the afterlife: you only go to Heaven if you still have your tonsils, and Heaven’s located on Pluto. Politico is now looking to cut a deal with Kid to acquire the mirror. Death has the mirror, and shows it to each of them in turn. Whore performs ‘Whore’s Poem’ that starts ‘I heard men say she loved a lantern fish’. As they look in the mirror, Kid sees himself in a vast landscape, while Politico sees the Virgin Mary in a mansion. The Gangster arrives, and Kid, Whore and Politico learn that they are to die and depart for the afterlife. Gangster – who reveals himself to be another of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Pestilence – now performs ‘Another Suburban Romance’, after which Death pays Gangster for delivering the other three to him.

We can see here hints of Moore’s interests in Americana. There is also a seedy cabaret vibe that recurs in a number of his other works. But Another Suburban Romance is an early piece, designed to play to the strengths of specific performers. Moore seems to have written the part of Gangster for himself to perform: we know he wrote the character’s songs, as he received sole credit for them in the Avatar adaptation, while Gangster has a similar persona (and gruff American accent) to the narrator of Brought to Light (1989), which Moore would later adapt into a performance piece. From the fact that Scene Four is longer than the others, twelve pages out of a total of twenty-nine, and shifts the focus from Gangster to Death, we might speculate that although Moore wrote the majority of the first half of the play, Delano was responsible for the second.

Soon afterwards, Moore and Alex Green started a band, taking a name from a Wallace Stevens poem, The Emperors of Ice Cream. Once they had an album’s worth of material – a process that apparently took around a year – they advertised for musicians in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo in October 1978. One respondent was David J. Haskins, who met Green but had to decline the opportunity to become a member as he had just joined another band. This was Bauhaus, now usually considered the earliest goth group, whose debut single ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ quickly led to a session on John Peel’s Radio One show. Moore did not meet David J until a little later, but theirs would prove to be a lasting creative partnership. The Emperors of Ice Cream, however, neither performed nor recorded. Alex Green has referred to the project as ‘the dream band that never got beyond rehearsals’.

In the summer of 1979, another friend of Moore’s from the Arts Group days, Mr Liquorice, opened the Deadly Fun Hippodrome, an afternoon venue for local and visiting musicians. David J has said Moore was ‘partly behind’ the venture, and described it as ‘a mad anarchic surrealist cabaret … all the eccentric artists in Northampton would crawl out of the woodwork and turn up for this event … It was held in an old Edwardian pavilion in the middle of the Northampton race course.’ According to Moore, ‘over the single summer of its brief duration it built up a loyal audience of, literally, dozens’. One afternoon, there was a gap in the schedule, and Moore formed an impromptu band consisting of himself, David J, Alex Green (who by now had the stage name Max Akropolis) and Glyn Bush (aka Grant Series, from the Birmingham band De-go-Tees). They called themselves the Sinister Ducks, played for half an hour and ‘didn’t rehearse or even speak to each other’ for another two years afterwards. The spirit of the Arts Lab clearly lived on, with Moore and his mates having fun creating impromptu cabaret-style shows that were evidently more of an elaborate private joke than anything akin to a workable public performance.

Meanwhile, Moore was still following comics. Fifteen years on from the launch of Fantastic Four, Marvel had continued to mature with their audience. DC had responded, and American superhero comics were now vehicles for complex running stories with a smattering of social conscience. Future novelists Jonathan Lethem and Michael Chabon – both around ten years younger than Moore – were among those inspired by the Marvel and DC comics of the seventies. In his book of essays Manhood for Amateurs, Chabon waxes lyrical about comics of his youth, and particularly Big Barda, a character from DC’s Fourth World (1970–3). This was Jack Kirby’s infectiously bizarre space-age reinterpretation of folklore archetypes that explored cosmic war between good guys called Highfather and Lightray, and evil personified by beings with names like Darkseid and Virman Vundabar. In 2007, Marvel would publish Lethem’s take on their equally weird, equally cosmic character from the seventies, Omega the Unknown (1976–7).

Moore continued to read American superhero comics – ‘by the time I was in my middle twenties, I was still occasionally reading the odd Marvel or DC comic just to see if anything interesting was happening’ – but had all but stopped attending comics marts and conventions. He agreed with Steve Moore that fandom was becoming obsessed with the past, when it should be striving to improve the quality of storytelling in new comics, and tellingly he didn’t contribute to any fanzines. He did, however, identify the Fourth World titles as a highlight: ‘We were all really thrilled by them. I remember at the comic convention where I actually saw some early copies of Jimmy Olsen work, just how excited everybody was just to see them coming out … we were all absolutely devastated when the books seemed to finish without a proper ending.’ This interest continued throughout the seventies – Moore has noted, ‘I remember reading Frank Miller’s first stuff on Daredevil, and thinking, “Oh, this was worth buying all those crap comics for; this is something interesting, I can follow this”.’ Miller’s run on Daredevil began in May 1979, and introduced a noir sensibility to what had been a run-of-the-mill series about an acrobatic superhero.

Two comics in particular spurred Moore on to become a comics creator, not just a reader. The first was Arcade: The Comics Revue (1975–6), edited by prominent members of the San Francisco underground scene, Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith, and designed as a showcase for the best in comics for adults. Moore discovered back issues in the London shop Dark They Were and Golden-Eyed and quickly concluded that the lavish magazine contained ‘a collection of comic material that swiftly elevated Arcade: The Comics Revue to the Olympian reaches of my Three Favourite Comics Ever In The History Of The Universe. As is usually the way when I encounter something I’m really fond of, my condition escalated rapidly from good natured boyish enthusiasm to an embarrassing display of slobbering hysteria.’ Over twenty years later, Moore would explain that he felt ‘Arcade was perhaps the last of the original wave of underground comix, as well as their finest hour … As well as showcasing new and radically different artists, Arcade also seemed somehow to encourage work from underground artists of long standing that ranked amongst the best they’d ever done.’ Arcade #4 included Stalin by Spain Rodriguez, which Moore ‘ranks as one of my favourite single comic strip pieces of all time’. He was spurred on to write an effusive fan letter to the editors and, in late September 1976, received the following reply from Bill Griffith:

Alan,

Thanks for the entertaining letter. Seeing as it was of such a high intellectual calibre, we’ll most likely print it in our next issue … You almost found us too late. No 7 is just out and No 8 (out in 6–10 months) will be our last as a magazine. After that we go annual, in paperback form. I’m afraid we’re a bit too avant-garde for the Mafia.

Tally ho,

Griffy.

In the event, though, #7 was the last.

In 1984, Moore wrote ‘Too Avant Garde for the Mafia’, an essay for the fanzine Infinity which surveyed the seven issues of Arcade and their contributors. He concluded:

Arcade was an almost perfect culmination of the whole idea of Underground Comix. Granted, there have been worthy individual efforts by the various Arcade contributors since then, but somehow without the same flair … Balance is what Arcade achieved, in a nutshell. It balanced Griffith’s metaphysical slapstick against Spiegelman’s thirst for self-referential comic material and ground their more explosive experiments with a solid anchor of Robert Crumb’s simple and unadorned storytelling. It pushed the medium in all sorts of new directions, the vast majority of which still remain to be properly explored almost ten years later. Anyone seriously interested in seeing what directions comics might go in the future could do a lot worse than checking out just how far they’ve been in the not too distant past.

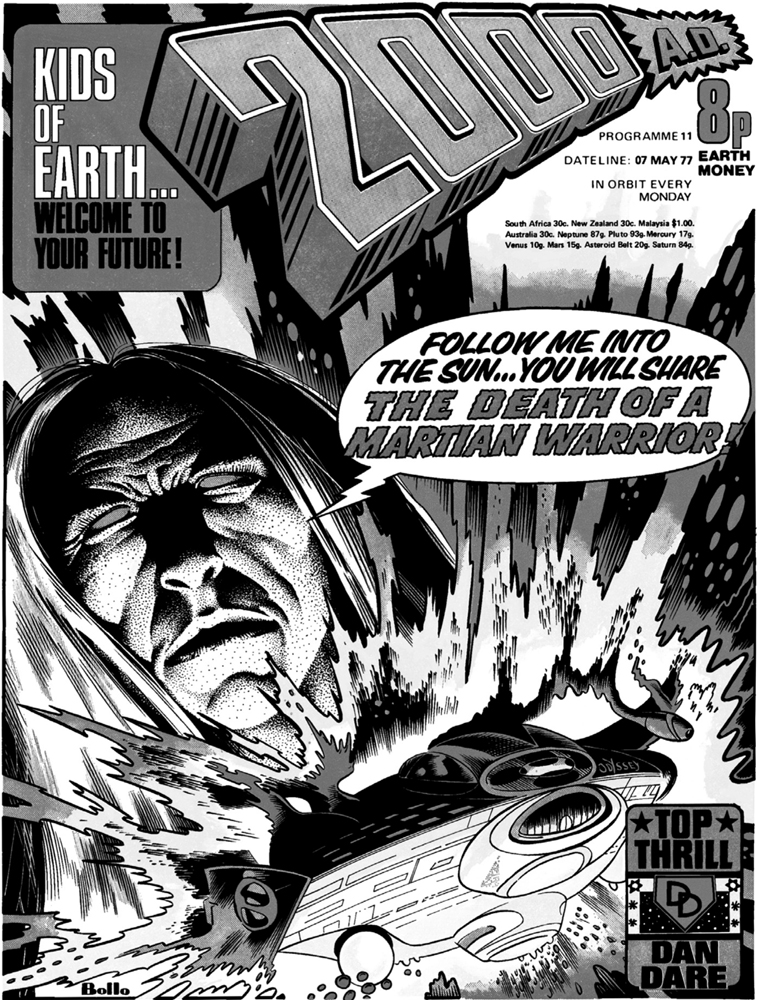

On the face of it, the second comic to inspire Moore could not have been more different. 2000AD was a weekly science fiction comic for boys that launched in February 1977 (and is still running today). It was published by IPC, publishers of children’s comics like Whizzer & Chips and Roy of the Rovers, and the early issues came with free gifts like a ‘space spinner’ and stickers. It had evolved, though, from Action, a comic first published the previous February, then abruptly cancelled after tabloid outrage at the violence of strips like Look Out for Lefty, about football hooligans, and Hellman of Hammer Force, whose protagonist was a Nazi tank commander. Over the next few years, 2000AD would thrill its audience with action-packed (i.e. violent) stories featuring characters like Dan Dare, Rogue Trooper, Strontium Dog, Nemesis the Warlock and Slaine – and, towering over all of them, future lawman Judge Dredd.

Picking up an early issue because he liked Brian Bolland’s cover (see following page), Moore was pleasantly surprised by the contents. He instinctively understood what 2000AD was trying to do, and recognised that it was attracting the top British comics talent. More than that, many of the contributors were writers and artists Moore had known for years. ‘When I was getting into comics, I’d recognised Dave Gibbons and Brian Bolland’s work in 2000AD, I’d recognised those names and those styles from the underground magazines of ten years before. Ian Gibson, he’d done some stuff in Steve Moore’s Orpheus fanzine. So a lot of these names, I recognised them from fandom, or from the underground.’ But that wasn’t what drew him to the comic. As he explained elsewhere: ‘You’d got really funny, cynical writers working on 2000AD at that time. This was mainly Pat Mills and John Wagner, who had previously spent eleven years working on the British girls’ comics. And they had grown cynical and possibly actually evil during this time.’ Wagner, continued Moore, had once written a script called The Blind Ballerina, in which the title character would find herself in increasingly dire situations:

At the end of each episode you’d have her evil Uncle saying, ‘Yes, come with me. You’re going out on to the stage of the Albert Hall where you’re going to give your premiere performance’ and it’s the fast lane of the M1. And she’s sort of pirouetting and there’s trucks bearing down on her … hell, they were funny even in the girls’ comics. But when John got a science fiction comic to play with he could really amp up the humour. I saw this stuff and thought these people were intelligent, there’s satirical stuff, I could maybe write something that would play to this audience and would also be interesting for me to write.

Moore understood that the creators were sneaking in political and subversive material. Broad satire, to be sure, but Judge Dredd routinely took ‘tough policing’ firmly into the realms of police brutality, if not fascism, and the strip made clear that, in large part, the endemic crime in Mega-City One was a result of social injustice. More to the point, the editors needed to fill pages every week. Finally, there was a venue for the sort of stories Alan Moore wanted to write, and they were hiring new writers.

Alan Moore was twenty-four the year 2000AD launched. He’d switched employers from Kelly Brothers to Pipeline Constructors Ltd – another office job processing paperwork for a company that supplied and fitted pipes for the Gas Board – while he and Phyllis had moved to a brand new council house in Blackthorn. In the autumn of 1977, Phyllis Moore was pregnant. This represented a decision point for Alan: ‘I was married and we had our first child on the way. I always had a vague idea that it would be nice at some point in the future to actually make my living out of doing something that I enjoyed rather than something I despised which was, like, everything other than comics. So, I figured that my wife was pregnant, if I didn’t give up the job and make a stab at some kind of artistic career before the baby was born that, I know the limits of my courage, I wouldn’t have been up for doing it after I’ve got these big, imploring eyes staring up at me. So, I quit.’

With the benefit payments Alan and Phyllis Moore received amounting to £42.50 a week, ‘the bare minimum they needed to live on’, Moore determined that he would measure his success by his ability to earn more through his writing. So he buckled down to the task of becoming a professional comics writer, embarking on a space opera with the projected title Sun Dodgers which he thought he could write and draw for 2000AD, ‘an epic that I could’ve easily filled 300 pages with. A massive story that made Lord of the Rings look like a five-minute read’.

It was all in my head … there was a group of superheroes in space, with a science fiction explanation for each of these characters. They were a motley crew in a spaceship, probably going back the kind of strips Wally Wood was doing in witzend and The Misfits … I can remember somebody looked a bit like a futuristic samurai. A humanoid robot thing with a big steel ball for a head, which probably surfaced later as the Hypernaut in 1963. There was a half-human, half-canine creature who ended up as Wardog in the Special Executive. Thinking back, there was a character whose name was Five, and my vague idea was that he was a mental patient of undefined but unusual abilities who had been kept in a particular room, room five, that might have been an element which fed into V for Vendetta.

Moore got very little of this down on paper. ‘I think about six months later I’d got one page half pencilled, some inks. I just thought, “Why am I doing this?” I realised it was because I was never going to finish it.’

He sought practical advice from Steve Moore, who by this point was making a living selling comic scripts, and who gently explained that 2000AD wouldn’t just give a new writer a regular series. Writers and artists were expected to start their careers with one-off, self-contained pieces that were typically two to five pages long. Most British comics had slots for stories of this type, not because they allowed editors to test new talent so much as because they allowed for a far more flexible schedule than a roster of regular titles. In 2000AD these shorter pieces were published in the series Future Shocks and Time Twisters. Future star writers like Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison and Pete Milligan would all start at 2000AD by writing Future Shocks; it was how most writers and artists got their break for the magazine. The original idea, and name, for Future Shocks is usually credited to Steve Moore himself, and he certainly wrote the first story to appear under that banner (‘King of the World’ in #25, 13 August 1977), although such stories had a venerable heritage dating back at least as far as the EC Horror and SF comics of the fifties. Wherever they appeared, the strips tended to be fairly generic tales with a very limited repertoire of twist endings – most concluded with the protagonist dying because he wasn’t careful what he wished for, or his greed had led him to walk into a trap, or he didn’t realise his world was merely a simulation, or he was rude to someone who was secretly some kind of monster.

Abandoning his space opera, Alan wrote instead a thirty-panel Judge Dredd script, ‘Something Nasty in Mega-City One!!’, complete with design sketches. Steve Moore gave him advice about formatting the script and warned of common mistakes: a writer shouldn’t have overlong dialogue; captions aren’t needed to convey information shown in that panel’s picture; one panel can’t (usually) convey a sequence of events or even motion, much of the skill is in deciding which exact moment will appear in every panel. The Dredd script was rejected by 2000AD assistant editor Alan Grant, but he encouraged Moore to submit further ideas.

In an article for Warrior published five years later, Steve Moore described his own rise, ‘the long way … joined Odhams Press as an office boy, way back in 1967 … then worked my way up through sub-editor. Started on Pow! and Smash! … ended up at IPC’. The new generation of British comics writers – people like himself, Alan Grant, Steve Parkhouse and Pat Mills – had all started out as junior editors on the staff of comics companies in the late sixties, spending a decade learning their craft and the trade, mainly by reading lots of scripts, networking and seeing the commissioning process from the editor’s point of view. Steve Moore noted that ‘the other way is how Alan Moore came into the business … by bombarding people with scripts from outside’. Moore says: ‘I don’t think Steve was saying that through gritted teeth, so much as noting he’d never actually seen it done that way before.’ He has described his method of breaking into the comics industry as ‘a matter of going round the back, poisoning the dogs and going over the fence’.

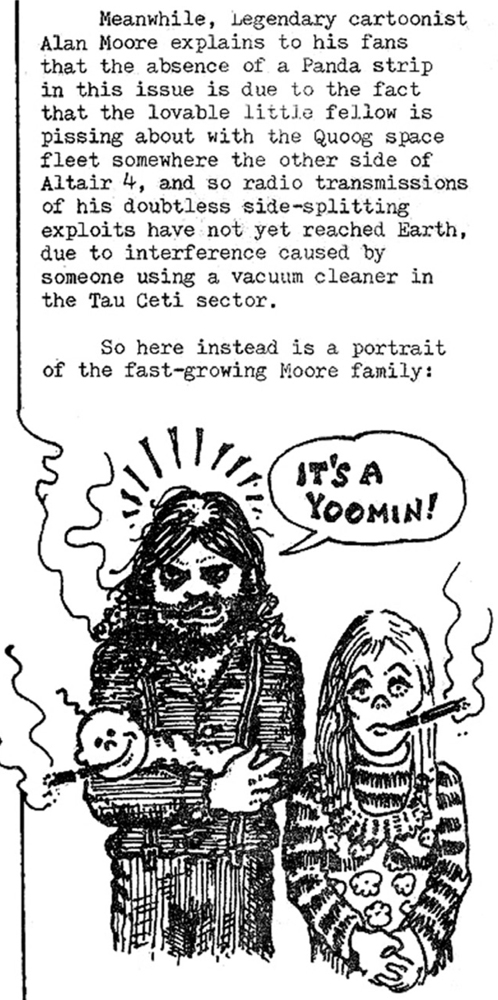

Moore was not looking to write only for 2000AD. He cast his net anywhere he found that published comic strips – places like newspapers, underground zines and the music press. And his persistence started to pay off. He was contacted by Dick Foreman, editor of The Back-Street Bugle, a fortnightly, Oxford-based alternative paper, who’d been told about Moore by a couple of Arts Lab alumni who’d moved to the town, Ant and Jackie Knight. Moore was offered a full-page strip, and came up with St Pancras Panda. This series is usually described as a pastiche of the children’s character Paddington Bear, but in fact it is basically a pretext for Moore to be increasingly mean to a sweet little panda. The tone is set in the first part, where our hero is rounded up along with Winnie the Pooh, the Dandy’s Biffo the Bear and Dougal from The Magic Roundabout and consigned to a furrier’s. ‘I was still drawing benefits and I still hadn’t really got around to submitting anything professionally, but working on the strip I did for The Back-Street Bugle, St Pancras Panda, I was able to meet deadlines, I was able to find how much time I needed to get the strip looking the way I wanted … So that was quite an important magazine, and it was uncovering dirty doings at the local council, it was covering local rock gigs, local alternative activities, very entertaining, very informative.’

St Pancras Panda looks sumptuous compared with Anon E. Mouse, although Moore put this down to a simple trick, rather than any improvement in his ability to draw: ‘I used to cover each picture in tiny stippled dots. For some reason editors love stippling. They buy your work every time. I think, personally, that this is because they feel sorry for you’. He used ten to fifteen small panels per instalment, packing each panel with detail, including Kurtzman-style sight gags. St Pancras Panda made its debut in The Back-Street Bugle #6. This was published only a few days after the Moores’ first daughter, Leah, was born on 4 February 1978, an event Moore would mark with an illustration for the Bugle.

Moore’s first professional work came in late 1978, when he submitted illustrations to Neil Spencer at the New Musical Express (NME). Spencer had been an associate of the Northampton Arts Lab and paid Moore £40 each for pictures of Elvis Costello (published 21 October 1978) and Malcolm McLaren (11 November 1978).

This did not lead to regular work for NME; a third illustration depicting Siouxsie and the Banshees was rejected (Moore then submitted it to the Back-Street Bugle, and there’s a note in #24 saying they hadn’t got room to run it). Having the NME on his CV, though, Moore was able to get his foot in the door in other parts of the music press.

Dark Star was a British magazine that had started in 1975 by covering west coast music, but had come to embrace British bands like The Teardrop Explodes and Echo and the Bunnymen, and was – a little anachronistically by the end of the seventies – rooted in the underground magazine aesthetic: reporting on Moore’s success, The Back-Street Bugle described it as ‘a magazine for ageing hippies’. Moore was commissioned to write and draw a series called The Avenging Hunchback, a broad parody of Superman (‘our saga begins upon the planet Krapton, a gigantic boil on the bum of the galaxy’), the first episode of which appeared in #19 (March 1979). When the second instalment was lost – the editor’s car having been stolen with the original artwork inside – Moore could not face redrawing it and instead was allowed to produce a series of one-off stories. The first was Kultural Krime Comix (#20, April 1979) – a strip he also starred in, appearing in ‘the vast Alan Moore Studios’ alongside a crowd of his creations, such as Anon E. Mouse and St Pancras Panda, lamenting the loss of the second Avenging Hunchback chapter. He then teamed up with Steve Moore for Talcum Powder (#21) and the more substantial Three-Eyes McGurk and his Death-Planet Commandos (#22–25), the latter a four-part strip drawn by Alan, written and inked by Steve. It included the first appearance of the character Axel Pressbutton, a psychotic cyborg who would end up in his The Stars My Degradation (1980–3) and Steve Moore’s Laser Eraser and Pressbutton (1982–6). Moore had designed a bald character with one eye bigger than the other, Lex Loopy, to be the villain of The Avenging Hunchback, but instead used the design for Pressbutton.

Again, the work for Dark Star was unpaid, but it was in a nationally distributed magazine and so appeared in newsagents around the country. In April 1981, Three Eyes McGurk and his Death-Planet Commandos would become his first piece to be published in America, when it was reprinted in Gilbert Shelton’s underground anthology, Rip-Off Comics #8.

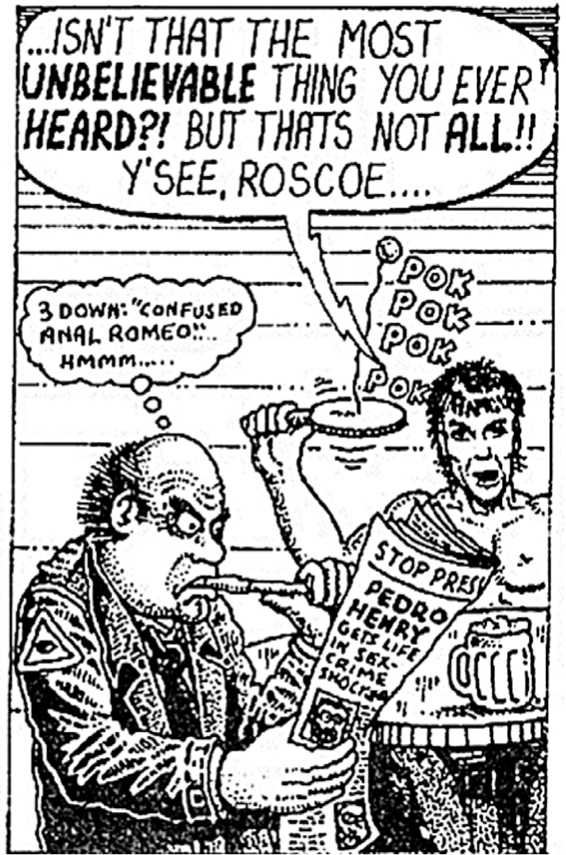

Very shortly after starting work for Dark Star, Moore finally secured a regular job that paid. This was Roscoe Moscow, a half-page strip for the weekly music magazine Sounds.

Something just happened in my head one day and I did two episodes of a strip called Roscoe Moscow, which was a surreal private eye strip that owed more than a little to Art Spiegelman’s Ace Hole. What I owed to it was the idea of a self-referential private eye who talks in the third person, somebody who talks in self-conscious Chandlerese, if you like. I sent in the first two episodes of that and got a telegram back – because we weren’t on the telephone at that point – saying that they’d like me to do it as a regular strip … Sounds was a crummy British rock music weekly; it was quite low-minded in its way, but it did have an interesting array of cartoonists working for them. Savage Pencil had been their mainstay for a long time and he’d been doing half a page a week. Pete Milligan, Brendan McCarthy and Brett Ewins were working upon a punk science fiction nihilist-type rock comic strip for a number of weeks before I applied with Roscoe Moscow. Apparently, they’d run out of enthusiasm for their strip or something – I’m not sure of the entire story – but for one reason or another their strip was ending. Sounds had a gap for another comic strip and I just happened to send in Roscoe Moscow at the right time.

The first instalment appeared in the 31 March 1979 issue of Sounds. The paper had a reported circulation of 250,000 copies a week, which if true would mean it was bought by more people than any other publication featuring Moore’s work – in either Britain or America – until he wrote for Image in the early nineties. The £35 a week Moore got for writing and drawing Roscoe Moscow was not quite enough to live on, though, and he adopted a pseudonym to hide his earnings. For the next few years, ‘Curt Vile’ would prove to be prolific and multi-talented, also writing reviews and interviews, drawing spot illustrations for Sounds, contributing to other publications, and even appearing on a single by the Mystery Guests.

And Roscoe Moscow saw another leap in quality. While there is a nugget of truth in Moore’s assessment that he ‘was barely capable of drawing even simple objects in a way by which they might be recognised’, he never let that get in the way of an ambition to stretch the medium. In Roscoe Moscow he comes up with a number of imaginative panel designs and progressions. The main recurring joke, that the protagonist is delusional, allows Moore to contrast the first-person narration with what the reader can see, and he milks a lot of material from this. There are in-jokes in Roscoe Moscow so obscure that Moore could have expected literally only one or two other people to get them. With the benefit of hindsight and a few decades of Moore scholarship, it is fun to spot the cameo by St Pancras Panda, the blatant plug for the Bauhaus single ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ and a joint credit for a Christmas boardgame given to ‘Curt + Phyllis Vile’. In this panel, Moore both reveals his secret identity in a crossword puzzle and namechecks Steve Moore’s pseudonym.

Moore gained a certain cachet by having his own weekly comic strip. The Back-Street Bugle were clearly proud of him, even though he had to scale back his work for them. St Pancras Panda ended in March 1979 (#25), but Moore (or rather Curt Vile) would go on to contribute another dozen or so illustrations. The Bugle even marketed the very first piece of Alan Moore-related merchandise: #26 (April 1979) had an advert for a silkscreened poster ‘tastefully printed in lurocolor’ and sold for 50p. August’s #30 also ran a short feature on Moore’s Sounds work, ‘Roscoe Moscow’s St Pancras Panda’, announcing that two more instalments of St Pancras Panda were planned and that the series might be collected into a comic book.

Early in his career, Alan Moore was happy to identify himself as coming from underground comix roots. In 1982, he would tell artist Bryan Talbot that collaborating with him ‘will be the first time I’ve worked with an artist whose background is as solidly rooted in the underground as my own is’. But even by 1988, he was backtracking a little, framing his Sounds work as a way to sneak into the profession ‘by entering an area of comic book work that really didn’t have an awful lot going for it and wasn’t terribly popular’. In 2004 he said he had been ‘a kind of sub-underground cartoonist’; in 2010, ‘you can look at my early work and see for yourself. I was an average, undergroundish cartoonist who was just making things up from week to week and hoping that the glaring flaws wouldn’t be too apparent.’ Whatever his feelings about the context in which he was operating, though, Moore has never been keen on the work itself. In 1984, he said he regarded it ‘in the same way that anyone who’s served their apprenticeship in public would do. For the most part, I see it as a lot of poorly executed drivel’. In the early nineties, he observed: ‘There’s a lot of repulsive bilge in there; and an awful lot of honest effort in there as well. It’s not terribly memorable work, those first strips. It didn’t teach me anything about drawing. Well, it taught me that I couldn’t draw, which was a useful thing to know before I carried on too far with it …’ He does admit that ‘there were a couple of odd little episodes in there where it was nicely drawn, nicely conceived, there was a nice little gag or a nice little concept’, but its value was largely elsewhere: ‘it kept me alive for two or three years, and it gave me a hands-on education in comic strips.’

Moore has only ever allowed isolated examples of his underground work to be reprinted (although almost all of it can be found online), saying, ‘it will probably remain unpublished. I’m glad, it’s nice that it’s out there on the ’net. The thing is, I was doing my best at the time … I’m really glad that it’s out there, so people can see, but I’m glad that … I don’t even have to look at it!’

Moore was still searching for more mainstream opportunities, and pitched an idea to his local free newspaper, the Northants Post. This was Nutter’s Ruin, a parody of a village soap opera. He drew a half-page strip outlining the cast and their foibles; the characters included Elsie and Eric Nutter, brutal police constable Willard Turk, aristocratic Bradley and Belinda Reighley-Stupid and (in a presumably unconscious lift from Monty Python’s ‘Mr Hilter’ sketch), ‘Mr Adolph Hilton, a kindly old Austrian gent who moved to Nutter’s Ruin just after the War’.

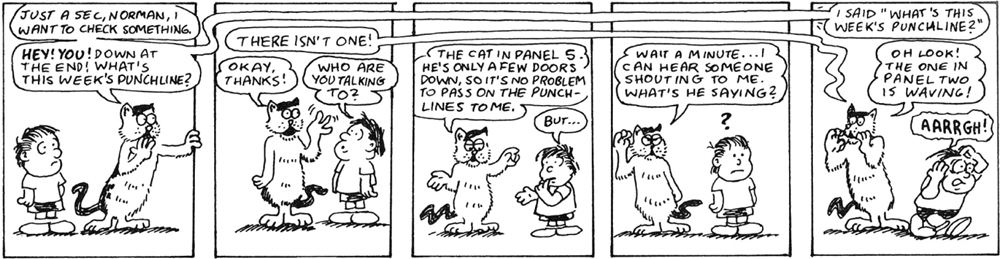

The paper’s editor liked Moore’s art but wanted something for children, and suggested ‘perhaps a strip about a little cat or something?’ So Moore came up with Maxwell the Magic Cat, basing the protagonist on his own cat, Tonto. The first strip appeared in the 25 August 1979 edition of the Northants Post. The drawing was technically primitive – more like the simple linework of Anon E. Mouse than the elaborate stippling of his Sounds work – but the jokes were funnier and more elaborate. Moore soon abandoned the idea of telling a running story and came to enjoy the challenge of coming up with a new five-panel gag week after week; because his deadline was only three days before publication, he could make the strip extremely topical. Moore chose to write the strip under the pseudonym Jill De Ray. As he has always taken great delight in recounting, Gilles de Rais was a fifteenth-century demon summoner, child molester and serial killer. Emboldened by having got that past his editor, Moore occasionally steered the strip into dark or overtly political territory, with a healthy regular dose of surrealism.

He enjoyed himself, and Maxwell the Magic Cat would continue to run until October 1986 – after the first issues of Watchmen had been published and Moore had become the most renowned writer of comics on the planet (a fact his Northants Post editors seemed blissfully unaware of). Artist Eddie Campbell’s prediction that the next generation of comics historians would reassess Maxwell and it ‘will be properly recognised as an important work’ hasn’t yet come to pass, but Campbell best explains the significance the strip holds in Moore’s canon: ‘Of all Alan’s work, Maxwell is the most immediate representation of the man’s thoughts and idle notions … they reach us without being modified by a collaborator or the complicated requirements of the big publishing houses’.

Moore was now earning £35 from Sounds and £10 from Maxwell the Magic Cat, more than the £42.50 he had been receiving in benefits. Honour satisfied, he signed off the dole and was now officially a full-time professional comics creator.

In May 1980 Sounds published a letter from reader Derek Hitchcock accusing Roscoe Moscow of being homophobic. Moore replied as Curt Vile, insisting that it was the character who was prejudiced, not the writer: ‘Curt Vile likes to think of himself as a friend to all the people, irrespective of class, colour, place of worship or whatever the hell they wish to do with their private parts’; in writing this, he wanted ‘to make absolutely sure that no impressionable adolescent ran away with the idea that I was outlining my own personal philosophy’. Since, at a number of points later in his career, Moore would worry that his audience were not spotting his ‘heavy irony’, this exchange may have been one factor that led to him begin to wind down Roscoe Moscow, its last chapter appearing in the 28 June 1980 edition. He began a new strip, The Stars My Degradation, the first instalment of which was published in July 1980. Dropping all references to the music industry, this was a broad parody of science fiction and superhero stories, the sprawling space opera that 2000AD would never have let him get away with. Meanwhile, Curt Vile had written glowing reviews of the Mystery Guests and Bauhaus, and Moore struggled with other conflicts of interest: ‘Occasionally I’d supplement my income by interviewing people like Hawkwind. Unfortunately if Nik Turner made me a cup of tea while I was interviewing them. I couldn’t write anything nasty about them. So I figured journalism wasn’t for me.’

Fortunately, there were new opportunities in mainstream comics conducive to the sort of work Moore was keen to write. Doctor Who Weekly debuted in late 1979, and was packed with articles about the popular BBC show, both the on-screen adventures of the time-travelling main character and what was going on the behind the scenes. Each issue contained two original comic strips: the first showcased adventures of the Doctor himself, the second was a shorter back-up strip featuring a parade of his old foes, like the Daleks and Cybermen. The latter had until now all been written by Steve Moore, but when from Doctor Who Weekly #35 (June 1980) he was promoted to the main strip, he tipped off Alan that they would be looking for a new writer, then passed his friend’s trial script, ‘Black Legacy’, to editor Paul Neary. It was accepted, and was published in the same issue Steve Moore took charge of the main strip. Alan was delighted to realise the artist was the same David Lloyd who, like him, had contributed to the fanzine Shadow as a teenager. ‘I felt that at the time David Lloyd’s strips as an artist were undervalued; he didn’t seem to be regarded in the same way that Dave Gibbons or even a relatively young artist like Steve Dillon would be regarded. The perception of David’s work back then seemed to be that he was a solid, meat and potato artist who you shouldn’t really expect anything spectacular from, but I saw more than that in David’s work. I saw a really powerful sense of storytelling and a starkness in his contrasts of black and white.’

Steve Moore had established a formula for the back-up strips. Generally the protagonist would venture somewhere they had been warned not to go, where they meddled with forces they did not understand – this tended to mean unleashing an old Doctor Who monster – with a nasty twist at the end when the protagonist thought they were finally safe. Alan had watched Doctor Who off and on over the years, but had not been much of a fan since William Hartnell left in 1966 (he had been twelve at the time). With ‘Black Legacy’, he followed Steve Moore’s template perhaps a little too faithfully, but once he had proved himself, he and Lloyd followed it up with the far more unsettling ‘Business as Usual’, a fast-paced story using the Autons – old monsters made from animated plastic, who infiltrated Earth by taking the form of toys and mannequins. Both stories required a degree of discipline new to Moore, but he enjoyed the challenge: ‘Two pages isn’t a lot for the reader to be able to remember even by the next week. You’ve got to kind of establish everything and have each little two-page section come to its own dramatic conclusion. It was trickier than it looked but it was a great way of learning how to write comics … the 300-page sci-fi epic was never going to work, whereas what I was now doing was actually starting from something really small.’ Each story consisted of eight pages in total, broken into four parts, with an increasingly tense cliffhanger each week, building up to the climax. ‘I’m not saying I did a great job of it but it seemed to work, and it is just the best way of learning how to write stories: start off with something that is too small, in your opinion, to tell a good story in and then find a way to tell a good story in that space.’

Alan’s last contribution to Doctor Who was what he has informally called the 4D War Cycle, stories set in the early years of the Doctor’s people, the Time Lords. This was an ambitious space opera spanning generations, with the Time Lords under attack from the Order of the Black Sun, a mysterious organisation from the future who are retaliating for some offence the Time Lords are yet to commit. The Doctor Who TV series had left the origins of the Time Lords a virtually blank slate, and Moore filled it with new characters. The stories are a short, sharp blending of high-concept science fiction and the superhero team book.

We’ve got the Order of the Black Sun, who are pretty clearly the Green Lantern Corps but with a different costumier. A gothic costumier. I liked the idea of the Gallifreyans established as a very, very powerful intergalactic force and it’s also not just intergalactic, it’s throughout the aeons, because they’ve mastered time travel. So that would make them very, very powerful in any possible universe full of different races. And so I thought you’re going to need somebody that is as big and powerful as the Gallifreyans if this is going to be a fair fight. So I started to think of something a bit like the Green Lantern Corps from DC’s Green Lantern comics. At that point there was no chance of me ever working for America, so it just seemed that this might be my only chance to do something that’s a bit like those American superheroes that I remember from my boyhood. So I brought in this intergalactic confederacy of different alien races who are all united under this banner of the Black Sun. And yes, I could have carried that on. I forget where I was going to take it. I presume that the battle would get bigger. Perhaps I’d get longer stories to tell it in.’

Moore had planned to write more stories in the 4D War Cycle, and believes he was next in line to write the main strip. Instead, he quit Doctor Who Monthly over a point of principle. One of Steve Moore’s strips had introduced Abslom Daak, Dalek Killer, a psychotic character ‘specifically created as a Pressbutton-style balance to the somewhat lightweight Doctor Who’: rather than offer the Daleks a jelly baby, Daak would slice them in half with his chainsword. Having first appeared in Doctor Who Weekly #17 (February 1980) and proved popular, Daak returned semi-regularly, and there was talk of a spin-off title. But when Steve Moore learned this was to be written by Alan McKenzie, he stopped working for Doctor Who Monthly and, as he says, ‘Alan Moore quit writing for the magazine too, in a wonderful gesture of support that was remarkable for someone at that early a stage in their career’. Alan’s last story was ‘Black Sun Rising’ in Doctor Who Monthly #57 (December 1981), although neither he nor Steve left Marvel UK altogether, and both picked up similar work in Empire Strikes Back Monthly.

Alan Moore had continued to send ideas to 2000AD’s editor, and ‘Alan [Grant] would write letters explaining why they were turned down. Eventually, he wrote a letter saying, “Look, if you just changed this, this and this, I think this one might be acceptable,” and on the second or third attempt, I got the form letter back which had lots of robots giving the thumbs up, which means you’ve been accepted.’

This story, ‘Killer in the Cab’ (#170, July 1980), was however beaten into print by Moore’s second commission, which appeared earlier the same month in the 2000AD Sci-Fi Special 1980. ‘Holiday in Hell’ was a five-page story with art by Dave Harwood. The story is almost a textbook iteration of the Future Shocks formula. First, the science fiction high concept: Earth of the future is ‘a world without war, without crime, without bloodshed’, but people book holidays on Mars to let off steam by attacking ‘victimatics’, perfect robot duplicates of people who ‘show terror … pain … suffering’ as they are chopped up or shot. Then we see a ‘normal’ young couple, George and Gabrielle, enjoy themselves on Mars by brutally attacking victimatics before returning to Earth. Except there’s a twist: the real Gabrielle has been replaced by a duplicate who kills George and reveals ‘we victimatics need to take a holiday every now and again, too!’ and that half the tourists who’ve returned to Earth are actually killer robots. And so the rampage begins.

With his foot in the door and a little more experience, Moore found it much easier to get commissioned by 2000AD, and his work – at this stage confined to more Future Shocks – was soon appearing in the comic roughly every six weeks. While he continued to write and draw his Sounds strip and Maxwell the Magic Cat, Moore’s contributions to Marvel UK and 2000AD were solely as a scriptwriter. Not only was he acutely aware that he lacked the technical flair of the regular 2000AD artists, there was also the practical matter that even half a page for weekly Sounds often took him most of the week to draw; he just was not fast enough to produce the page a day he would need if he were to work for 2000AD. He found he could describe a panel in a script far more effectively than he could ever illustrate it himself.

Moore had a clear ambition for 2000AD: ‘At the time, I really, really wanted a regular strip. I didn’t want to do short stories. I wanted to do regular, ongoing series that would bring in regular money. But that wasn’t what I was being offered. I was being offered short four or five page stories where everything had to be done in those five pages. And, looking back, it was the best possible education that I could have had in how to construct a story.’ Moore came to relish the challenge of developing new twists and ever more elaborate story structures: ‘I did realise that in having done a couple of years of a weekly comic strip that I had, almost incidentally, learned how to tell a serialised story … I had learned something about the mechanics of telling a story on demand every week that was at least interesting enough to keep the readers entertained and to stop the editor from replacing it with something more commercial.’ Moore got into the habit of packing his pages with information and cutting out padding. He got to work with many different artists, and was fascinated to discover the ways different people interpreted his scripts and how it led to a broad range of types of creative partnership, from full and enthusiastic collaboration to an artist wilfully ignoring the script.

It was a key shift, creatively, for Moore, and one that marked him out as a writer who was particularly enthusiastic and thoughtful. Steve Parkhouse, already established by this time as an editor, writer and artist, would go on to collaborate with Moore, most notably on The Bojeffries Saga (1983–4); he has identified Moore’s great gift as ‘the ability to write exactly what the artist wants to draw’.

Moore found he was able to create a few running stories within the one-off format: ‘I really wanted to be doing a continuing character. If you were getting regular short story work, one way of doing that was by creating continuing characters or some other form of continuity that linked up your short stories. In 2000AD I’d done a few stories about a character called Abelard Snazz, “The Double-Decker Dome”. He was based upon an optical illusion drawing I’d seen of a man with two sets of eyes which was quite a disturbing thing, visually.’ If it went down well, he thought, then he might even get a series out of it: ‘If I can come up with a popular character and maybe link up some of these short stories so that they make a bigger narrative to show that I can handle … a longer story arc, then maybe that will work out as some future work. I suppose that was the simple mercenary thinking that was behind it.’

Abelard Snazz was introduced in the fourth of Moore’s published 2000AD stories, ‘The Final Solution’ (#189–90, December 1980, art: Steve Dillon) and the character would eventually feature in eight issues spread over two years. Moore had created his first recurring character for 2000AD. Snazz was a genius who would ‘handle complex problems with even more complicated solutions’. In his first story he solved a planet’s crimewave by inventing robot policemen, who promptly established a police state; to solve this new problem, he created robot criminals who were a match for the policemen. To solve the further problem that so many civilians were then caught in the crossfire between ruthless robot police and robot criminals, Snazz’s masterstroke was to create a population of robot civilians, and the human population were forced to leave their planet.

Moore was now a visible part of the London comics scene, whose writers, artists and editors would meet up under the aegis of the Society of Strip Illustration (SSI) and compare notes. Shortly after Moore joined, his Doctor Who artist David Lloyd became chairman. As Lloyd explains, ‘it started in 1977 as something of a glorified lunch club, with a lot of the really great Fleet Street cartoonists and artists. It recruited some of the guys from 2000AD and some of the other comics out there, and it was mostly a young organisation at the time … we had meetings initially at the Press Club, which was a great, posh place on Shoe Lane just off Fleet Street … if people walked in without a tie, they were frowned upon and it was kind of ridiculous to control that, particularly with comic artists. Later on we moved to various pubs, the George at the top of Fleet Street, then we moved to the Sketch Club in Chelsea … The Sketch Club is where we were at for the longest time, and it was very good, very vibrant.’ There were about forty members, all established comics creators, with two associate members who hadn’t been published by that point: Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean. Eddie Campbell, who at the time was based in London and self-publishing autobiographical comics, scathingly depicted the SSI – and Lloyd – as ‘an association of professionals … Status Quo is the new chairman. They meet upstairs at a pub’. Moore had been welcomed into the group and was much more warmly inclined to it, later describing the SSI as ‘at its best a kind of coffee evening, or rather where you could meet up at a bar … there were some very nice people there’. These included artists Moore would work with, such as Dave Gibbons, Alan Davis, Mark Farmer, Hunt Emerson, Garry Leach, Dave Harwood, David Lloyd and Mike Collins, as well as most of the editors who commissioned their work. Moore was now firmly in the loop.

Alan Moore had begun his attempt to become a professional comic strip creator around the time his wife Phyllis learned they were expecting their first daughter, Leah, who’d been born in February 1978. When the Moores’ younger daughter, Amber, was born three years later, Moore was well on his way. But this is not how it felt at the time, either for Moore, for anyone in the comics industry, or for his readers. He may have begun to earn himself a steady stream of commissions, and was becoming well known in the industry, but he was ‘having to work hard to get every little breakthrough to win an inch of ground’. It is only with the benefit of hindsight that we can see this as the beginning of a sure-footed, meteoric rise.