‘Working for Quality Comics is great! It’s cartoon heaven.’

Alan Moore, Fantasy Express #5 (1983)

In its May 1981 edition, the editor of the newsletter of the Society of Strip Illustration, David Lloyd, posed a series of questions to ‘five of the most respected and reputable strip writers in British comics’: Angus Allan, Pat Mills, Steve Moore, Steve Parkhouse and Alan Moore. The other four writers were stalwarts of the British comics scene: Allan, perhaps the least well known today, had been in the business since before Moore was born, and at the time of the interview he was writing virtually all the strips in Look-In, a children’s magazine that ran comic-strip versions of ITV shows like The Tomorrow People and Worzel Gummidge – and sold twice as many copies as 2000AD. Moore was very much a newcomer (this was his earliest published interview), but Lloyd had no hesitation inviting him to the ‘round table’ discussion (they weren’t in the same room – Lloyd had posted the same questions to each writer and collated the responses): ‘He became very famous and well known very quickly. He just happened to be brilliant, and accepted as brilliant, and everyone knew he was brilliant when they met him … There was no surprise with Alan reaching that position because everyone recognised how brilliant he was.’

Moore was twenty-seven years old, married, the father of two daughters, and the family had just moved across Northampton into a old-fashioned brick council house on Wallace Road. He was now freelancing for 2000AD and Marvel UK, but was yet to work on a regular series for either of them. It is clear from the interview that he was enjoying his job: ‘I find writing comics to be staggeringly easy … on an average day, working at a fairly leisurely pace, I can turn out a complete five-page script. On a tough day, I can turn out a couple and still be finished by the early evening … I love my work, although having previously been employed in cleaning toilets, this is perhaps less than surprising … I think I’m adequately payed [sic]. Actually, just between you and me, I’m grossly overpaid … I can turn out a four or five-page script in a single day and get a return of somewhere between sixty and ninety quid for my efforts. On top of this I get to buy ludicrous amounts of comics each month.’

We learn, too, that his 2000AD editor, Steve McManus, had set him the challenge of telling a story without wordy captions; Moore clearly relished the task, but felt the artist had ruined the final product. The artist in question was Walter Howarth, drawing ‘Southern Comfort’ for the 2000AD Sci-Fi Special (July 1980). This early in his career, Moore would have been keen to rack up as many credits as possible, but significantly the strip went out under the pseudonym ‘R.E. Wright’. Moore cited the forthcoming ‘Bax the Burner’ (2000AD Annual 1982, published August 1981), as a particular favourite, praising the artist Steve Dillon, and noting: ‘I was pleased inasmuch as the story was the only one in which I’ve hung the plot around a strong emotional content and not had the whole thing come off as being incredibly trite and sentimental.’

Moore was ambitious – ‘one day I’d like to have a crack at writing novels, short stories, TV and film scripts, stage plays, kiddie porn and all the rest of that stuff’ – but ‘at this point I can’t see comics as ever becoming anything less than my principal area of concern’. That ambition was not solely personal. His love of comics shines through, and for the first time – but by no means the last – he set down why: ‘To me the medium is possibly one of the most exciting and underdeveloped areas in the whole cultural spectrum. There’s a lot of virgin ground yet to be broken and a hell of a lot of things that haven’t been attempted. If I wasn’t infatuated with the medium I wouldn’t be working in it.’

This was not what most people working in the British comics industry saw. Twenty or so years later, fellow round-table contributor Steve Parkhouse would say:

IPC Juveniles were simply regurgitating ideas that were fifty years old. Recycling was the name of the game. Editorial staff were paid next to nothing, installed in draughty old buildings with creaking office furniture and expected to co-exist with the rats, the debris and the general malaise of Farringdon Street and its depressing environs. It was a cottage industry inhabited by middle-aged men in cardigans who smoked pipes. You could see them in the works canteen, spooning down vast quantities of jam roly-poly and custard while discussing the latest developments in model aircraft design.

Pat Mills was perhaps the highest-profile participant in the SSI round table. By any standards he was an energetic and innovative figure, someone who’d fought against the staid, complacent comics industry. Mills had written the acclaimed Charley’s War, a long-running series in the comic Battle, which followed an underage working-class lad into the trenches of the Somme without flinching from depictions of either brutality or the political context. It was he who had launched first the controversial, violent war comic Action, as well as 2000AD and its fellow SF title Starlord. For each of these comics, he had created, co-created, developed or written early scripts for virtually all the running characters (including Judge Dredd). At the time of the interview, Mills was working on the experimental, satirical, not to mention downright strange Nemesis the Warlock, a regular series for 2000AD with artist Kevin O’Neill. When asked the question ‘What ambitions do you have for strips as a whole?’, though, Mills’ reply was curt and practical: ‘Albums, rights – the usual thing. But I don’t see it happening. Publishers in this country like things the way they are and I don’t see anyone or anything altering their outlook.’

Moore was far more expansive. At the beginning of the eighties, he described the battlefield on which he would be fighting for the next decade, one he reasoned would involve changing the attitudes of publishers, editors, creators, readers and even society as a whole. It practically amounted to a manifesto:

There’s such a lot of things I’d like to see happen to comics over the next few years that it’s difficult knowing where to start.

I’d like to see less dependence upon the existing big comic companies. I’d like to see artists and writers working off their own bat to open up space for comic strips in magazines which might not have considered them before.

Secondly, I hope that kids’ comics in the eighties will realise what decade they’re in and stop turning out stuff with an intellectual and moral level rooted somewhere in the early fifties. Stories concerning the daring escapades of plucky Nobby Eichmann, Killer Commando decimating the buck-toothed Japs with his cheeky cockney humour and his chattering stengun don’t have a lot of immediate relevance to kids whose only exposure to war is the horribly grey mess that we’ve got in Northern Ireland. I’d like to see an erosion of the barrier between ‘boys’ and ‘girls’ comics. I’d like to see the sweaty, bull-necked masculine stereotype and the whimpering girly counterpart pushed one inch at a time through a Kenwood Chef.

I’d like to see, and this is purely whimsy, a return to old-fashioned little studio set ups like Eisner/Iger had in the thirties and forties. This would give the artists and writers a greater autonomy, since they’d be selling stuff to the company as a sort of package deal. It would give them a stronger [sic] the merchandising royalties. And I should imagine that some editors might be quite pleased to save time in commissioning one complete job rather than hassling round trying to commission two or three separate people.

I’d like to see an adult comic that didn’t predominantly feature huge tits, spilled intestines or the sort of brain-damaged, acid-casualty gibbering that Heavy Metal is so fond of.

In retrospect, it is striking how Moore’s frame of reference is purely the British comics scene. The ‘big comic companies’ he referred to were the UK’s IPC and DC Thomson, not American giants DC and Marvel. Will Eisner was invoked as a legendary creator from before Moore was born, not as the man who had just written and drawn Contract With God, the comic that was the first to have been described as a ‘graphic novel’. It does not even seem to have occurred to Moore that he might work for the American industry.

But Moore did have one more ambition: ‘My greatest personal hope is that someone will revive Marvelman and I’ll get to write it. KIMOTA!’ Of all the things he said in the interview, it was this throwaway line which would change the course of Moore’s career, and ultimately the direction of the British and American comics industries.

Alan Moore had just said the magic word.

Moore’s account of what happened next is that ‘Dez Skinn got in touch with me and said by a remarkable coincidence, he had been planning to revive Marvelman, and would I be interested in writing it?’ In reality, as ever, things were a little more complicated.

Dez Skinn was a key figure of British comics at the time, and certainly the most colourful. Only two years older than Moore, during the course of the seventies he had progressed from writing comics fanzines like Eureka and Derinn Comic Collector to working at IPC and Warner Publishing (where he devised the successful House of Hammer), and launching Starburst magazine. Having sold Starburst to Marvel UK he had become an editor there, revamping and launching numerous titles like Conan and Hulk Comic as well as Doctor Who Weekly. Along the way he had worked with just about every writer and artist on the British comics scene. Ever ambitious, Skinn had come to understand both that the audience for comics was getting a little older, and that many of the younger generation of creators were frustrated with how hidebound the industry was.

Bernadette (Bernie) Jaye remembers Skinn as ‘a blond-haired guy who was on a high, brimming with abundant energy and enthusiasm’. Jaye was a sociology student who had shown up at Marvel UK just to take a look around an art studio, but Skinn hired her on the spot as a freelance colourist before employing her fulltime. Soon to become an editor herself, in which capacity she was eventually to work with Moore, she remembers: ‘It was an incredible atmosphere. Working at Marvel was fun in the main. Most of the staff were aged twenty-something. We were often in the office late into the night meeting ridiculous deadlines or in the local pub … I hadn’t met any “creators” before and I certainly hadn’t met people with a passion for a medium that dated back to their childhood. To have viable status in this arena you needed to have a comics collection, an obsession for the historic details and to have contributed to fanzines. I hadn’t had any of these experiences, couldn’t contribute on any of these levels and as a female I had missed out on all sorts of rites of passage. I never swapped comics in the playground, hunted down comics on my bicycle, made my own comics or had my mother throw some of my comics collection away. What I could do was be supportive of the creators. I had appreciated the freelance work I received from Dez and could offer this opportunity now to others even though it was on a small scale.’

Most Marvel UK titles relied on reprints of American material. Skinn envisioned a comic that would be an anthology of half a dozen all-new strips, ranging across various genres, such as SF, sword-and-sorcery and superheroes. It was to be a showcase for British talent, and a launchpad for new characters. He planned to call it Warrior. Skinn has said he would have edited the comic for Marvel, but couldn’t get his bosses interested in a showcase for the emerging generation of writers and artists. As Jaye explains, ‘I don’t think providing work for creators was ever fully supported by the management. They didn’t have any history with comics and there was always the feeling it was tolerated rather than enjoyed and promoted. I always felt we were getting by on the blind side.’

So Skinn left Marvel to produce Warrior under the aegis of his own company, Quality Communications. In April 1981, just before the SSI roundtable was published, he began putting together the first issue, a process that would end up taking about a year. Pragmatically, he wanted the strips in Warrior to be as close as possible to the most popular strips in his old Marvel titles: ‘So instead of Captain Britain, we had Marvelman. Instead of Night-Raven, we had V for Vendetta. Instead of Abslom Daak … we had Axel Pressbutton. And instead of Conan we had Shandor.’ To that end, Skinn was talking to artists and writers he had worked with at Marvel. Many of the small band of established British comic-book freelancers were keen to work for Warrior, and over the next few years they were to do so.

Skinn wanted a superhero as part of the mix, and had already decided that would be Marvelman – the old character had fallen into obscurity since his titles were cancelled in 1963, but he was a British superhero and fans Skinn’s age would at least remember the name. Skinn originally hoped Steve Moore or Steve Parkhouse would write it, with Dave Gibbons or Brian Bolland drawing. But all four declined the opportunity, although they would all work on other strips for Warrior. Gibbons says Marvelman ‘appealed, but I was too busy’ and this was almost certainly the main reason Bolland declined as well.

For the writers, meanwhile, a factor in their decision to turn down Marvelman may have been that Warrior was going to allow writers and artists to retain the rights to characters they created. Traditionally, comic book publishers on both sides of the Atlantic had treated creators as hired hands. In 1938, when the American writer/artist team of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster sold all rights to the character Superman along with the first strip featuring him, they had been paid just $130. Forty years on, Superman was big business: Warner Communications now owned DC Comics, the publisher of Superman comics, and their movie division had released the blockbusters Superman: The Movie (1978) and Superman II (1980). Yet the corporation had been shamed into giving Siegel and Shuster pensions and on-screen credits only when it came to light that they were practically destitute.

There were no millions to be made or blockbuster movie adaptations in British comics, and creators enjoyed no glory for their efforts. Slowly, though, things were beginning to change: soon after 2000AD launched, it had started to put credits on stories, and this revolutionary move had quickly become standard practice. Even so, all the revenue from foreign and domestic reprints, merchandise and other spin-offs remained with the publishers. With Warrior giving writers and artists the luxury of retaining the rights to any new creations, it would make far more sense for them to work on their own characters rather than revive someone else’s.

Another factor was that superheroes had never caught on in the UK. Since the heyday of Dan Dare in the fifties the most popular British adventure comics had consistently been science fiction. The popularity of 2000AD, the arrival of Star Wars and a spike of popularity for Doctor Who – both the subject of weekly comics published by Marvel UK – had only cemented that in the late seventies. It was science fiction character Axel Pressbutton who would feature on the cover of Warrior #1 – which proclaimed ‘He’s Back!’, although the character’s very first appearance had been all of three years before and he was still appearing every week in Sounds – and it was Pressbutton who Dez Skinn assumed would be Warrior’s signature character. The strip would be written by Steve Moore (using his ‘Pedro Henry’ pseudonym), and abandoned the ‘underground comix’ sensibility of Pressbutton’s previous appearances. Instead he would star in an action series in a very similar vein to Steve Moore’s Abslom Daak, using the same artist, Steve Dillon. Except for having a little more violence and bare skin, Warrior’s version of Pressbutton would not have been out of place in 2000AD.

Dez Skinn says that when Steve Moore turned down the opportunity to write Marvelman, he mentioned he had a friend who ‘would kill for the chance’. Alan Moore has suggested that Skinn ‘must have seen the thing in the SSI Journal’, and would later recall that when David Lloyd was asked by Skinn to create another series, a ‘new thirties mystery strip’ for Warrior, Lloyd ‘suggested me as writer’. Taken together, these varying recollections leave the actual sequence of events unclear, but all parties agree that Moore was involved with Marvelman before the mystery strip. Skinn says that Lloyd’s recommendation came ‘perhaps a month later’ than Steve Moore’s, and ‘when David suggested Alan … I’d already seen his first Marvelman script’; Lloyd states that Moore ‘had already said yes to doing the Marvelman update’.

Skinn had been keen to work only with people he knew, but was surprised to find he already had Alan Moore’s name in his address book. Around eighteen months before, Moore had drawn a couple of pages of single-panel Christmas-themed gags for Frantic, a Marvel title Skinn had been editing. And Moore knew all about Dez Skinn. He had subscribed to Skinn’s fanzines a decade before, and had ‘seen him then, although I probably hadn’t necessarily met him’ at various comics marts and conventions. He thinks he first met Skinn when he hand-delivered his art to Frantic, but Skinn doesn’t recall this, and we should probably concede his point that most people who meet Alan Moore remember doing so.

Moore was not an old colleague, or anything like as seasoned as the rest of the creators being lined up for Warrior, but if he was as well-known in the industry as David Lloyd said, shouldn’t Dez Skinn have heard of him? Skinn did not remember Moore’s Frantic work, and says at the time he wasn’t reading Doctor Who Weekly or 2000AD, where strips by Moore were now appearing. Steve Moore was talking to Skinn about using the Pressbutton character. Wouldn’t Skinn have been aware of Alan from the Sounds strip Pressbutton appeared in, given that he was its artist? ‘You’d expect so, but to me Alan had been very much an “underground” one-off contributor (to Frantic). I’d even put such after his name in my mammoth address book so I’d remember who he was (failed though!) … Steve Dillon was to draw the strip, so Alan’s relevance was purely historical, no more than Mick Anglo and Marvelman.’

At Skinn’s request, Moore prepared an eight-page pitch document for Marvelman, which outlined the main characters and the backstory in some detail. Moore was clearly not in the loop at Warrior at this point: at the end of the pitch, he suggested Dave Gibbons or Steve Dillon as suitable artists, unaware Gibbons had already turned down the opportunity, and that there were other plans for Dillon. But the pitch led to a phone conversation, which persuaded Skinn to request a full script for the first instalment, although he made it clear that this was ‘on spec’ – in other words, Moore wouldn’t get paid if Skinn didn’t like it.

One of the first things Skinn had done when he started putting Warrior together was approach David Lloyd asking him to create a ‘Night-Raven-type’ series. Night-Raven was a prime example of why Skinn had been frustrated at Marvel UK. A Marvel comic from America was, and still is, typically a monthly printed in full colour, with around twenty-two pages of one story featuring one character (Captain America, say) or one team (such as The X-Men). A typical British title was a black-and-white weekly with larger pages and around half a dozen short strips, each featuring a different character. Some comics were padded out with text features – articles about the characters, prose fiction. Marvel UK’s comics were mostly straight reprints of American material (often broken up into shorter instalments, and always in black and white), but there would also occasionally be new material by British writers and artists featuring Marvel’s American characters like the Hulk. There were even some original characters. British readers were treated, for example, to the all-new adventures of Captain Britain.

Night-Raven was one of these characters. Created in 1979 for Marvel UK’s Hulk Comic by Skinn and assistant editor Richard Burton, it was written by Steve Parkhouse, drawn by Lloyd, and saw a masked vigilante take on gangsters in the 1930s. It owed a clear debt to venerable characters The Shadow and The Spirit, but had a distinct identity of its own, and while the stories notionally took place in the same ‘Marvel Universe’ as Fantastic Four, Iron Man and the rest, the series was set fifty years in the past, so it could plough its own furrow. Night-Raven was the favourite strip of many people working for Marvel UK. Despite this, Marvel’s American publisher, Stan Lee, insisted on changes after only a few months. He disliked Lloyd’s ‘blocky’ drawing style, and so John Bolton became the new artist. Lloyd was kept busy on other projects, including Star Wars, Doctor Who and an adaptation of the movie Time Bandits. The Night-Raven story was moved forward to the present day and the violence was toned down. Skinn saw this as symptomatic of the problems with the industry and, keen for Warrior to be a place where writers and artists would not be forced to make such compromises, he invited Lloyd to come up with a new series. Lloyd ‘knew it would be a much better piece of work if Alan was on board. I would have been happy to do something, but it would have had nothing like the depth that Alan would add to it.’ Many of the foundations of this ‘thirties mystery strip’, including its artist, had therefore been in place before Alan Moore was involved. Yet it would evolve into one of the series he is best known for: V for Vendetta.

Only two years later, when Moore wrote a ‘behind the scenes’ feature about the origins of V for Vendetta, he admitted that when he and Lloyd were asked where they got their ideas from, ‘we don’t really remember’. Once Skinn set them to work, however, they quickly had numerous telephone conversations and ‘voluminous correspondence’; both were clearly on the same wavelength and throwing a lot of ideas around. It was a true collaboration, with the artist working on some of the key story points and the writer putting a lot of thought into the visual style. ‘“Alan and I were like Laurel and Hardy when we worked on that,” Mr Lloyd said. “We clicked”.’

Recalling the ‘freakish terrorist in white face make-up who traded under the name of the Doll’ he had come up with for a DC Thomson competition about five years before, Moore suggested to Lloyd that the series could be about a character called Vendetta, along the lines of the Doll, rooted in a ‘realistic thirties’. This plan was quickly vetoed by Lloyd, who knew from experience that he would not enjoy the level of research and other restrictions this would entail. Lloyd had recently been approached by Serge Boissevain, a French editor who was preparing his own lavish adult comic for the English market, pssst! and Lloyd had come up with a single page for a proposed strip called Falconbridge. ‘The editor was crazy, he was this Frenchman and it was great he wanted to recruit people, but he had this rebellious attitude, and he would say “heroes are dead, so we’re not having heroes in my magazine” … So Evelina Falconbridge I just imagined would be an urban guerilla fighting these future fascists … It was just that one page. I sent it in as a sample, I did it in a kind of French style, used a shading technique on it that was a bit sub-Moebius. It didn’t work out.’

Moore and Lloyd agreed that, like Falconbridge, the series would be set in the 1990s, in a future totalitarian state. The writer, artist and editor were all keen to have a British setting, rather than an Americanised one. The initial idea ‘had robots, uniformed riot police of the kneepads and helmets variety’. Lloyd began coming up with character sketches for a rogue ‘future cop’ called Vendetta, incorporating the letter V in the costume. Vendetta would conduct a series of ‘bizarre murders’ in a plotline reminiscent of the Vincent Price movie The Abominable Dr Phibes. Lloyd was unhappy they hadn’t settled on a motive for their protagonist, and felt that without knowing what made him tick, it was impossible to come up with the right ‘look’ for him.

The world of the series had been devastated by nuclear war, but there wouldn’t be mutants or radioactive deserts. Not only were these clichéd, but the main issue was that 2000AD mainstay Judge Dredd was a future cop living in a corrupt post-apocalyptic city. While Skinn was keen for his characters to mirror existing successes, this would have been a little too close for comfort. But as V for Vendetta became less ‘futuristic’, more austere and Orwellian, it began instead to resemble another early 2000AD strip, Invasion!, about Bill Savage, fearless resistance leader of a near-future Britain invaded by a very thinly disguised Red Army. Most new comics series are built around combinations of old ideas, but Moore and Lloyd knew they needed to find a way to make their series more distinctive.

Getting to this stage had only taken a couple of weeks. A planned holiday at the end of June to the Isle of Wight with Phyllis, Leah and five-month old Amber now became a working break. Moore wrote the first Marvelman script and, as he put it in a handwritten comment on his covering letter to Skinn, a ‘rough synopsis for The Ace of Shades. This is only a first draft. It will hopefully have shaped up into something more complete by the time Dave gets my first script.’ Not even Moore liked the new title, which did not survive long. While he was writing up his notes, Skinn and his business partner Graham Marsh – not knowing that Moore and Lloyd had previously tossed around the title Vendetta – twisted the Churchillian slogan ‘V for Victory’ to come up with the title V for Vendetta. A memo by Skinn dated 24 June 1981 outlined the plans for Warrior and referred to ‘V for Vendetta, written by Alan Moore, drawn by David Lloyd. Set in a future Britain, around 1990. A totalitarian government, Big Brother sort of system. A mystery figure, Vendetta, takes on the system.’

In his ‘rough synopsis’, Moore had come up with a detailed backstory for the series, directly grounded in contemporary politics. A few months later, he would explain his working method to fellow artist and writer Bryan Talbot: ‘A sort of experiment I’m trying is to try and build the story from the characters upwards. This means that before I start on the actual script, I have to know who all the characters are and have a more or less complete life history for each one firmly established in my head.’ He would later tell the fanzine Hellfire, ‘what I did first was sit down and work out the entire world, all the stuff I’m never going to use in the strip, that you never need to know … once I’ve worked out the politics of the situation, how the government works and all the details like that, I can start thinking about the actual plotlines for individual episodes.’

The results of this cogitation were soon apparent. Moore sent Lloyd a detailed extrapolation of the consequences of a future Labour government unilaterally disarming the UK’s nuclear weapons; the Soviet Union was thus emboldened, leading to a nuclear war that left only the UK and China standing. The document got no closer to establishing their main character, though – Lloyd wrote on the sketch of ‘Vendetta’: ‘Just got your notes (28th June) so that makes all this redundant, but my general thoughts and opinions on the character remain unchanged. I’ll buzz you at the weekend,’ and sent it to Moore. The two of them were acutely aware that they were on to something. Moore had a list of things he wanted the strip to be like – including Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Shadow and Robin Hood – while Lloyd was coming up with a radical visual style for the series. Each panel would be a regular size, and pictures wouldn’t ‘bleed’ from them. It was a more extreme version of the ‘blocky’ art that Stan Lee had disliked so much. They were tantalisingly close, but still the strip was failing to crystallise.

Marvelman was proving far more straightforward. Moore submitted the first script to Dez Skinn, along with a cover letter apologising for ‘all the errors of typing, grammar and basic literacy that one must expect from a truly great artiste such as myself’, as well as for the fact that the story was a page longer than agreed, the ending was a little rushed and ‘some of the frames are a little word-heavy’. Skinn read the script on the bus and thought it was ‘stunning’. It followed the idea that had occurred to Moore back when he was a teenager: the boy Mike Moran had forgotten the magic word which allowed him to transform into Marvelman. Moran, now middle-aged, ended up in the middle of a heist to steal plutonium from a power station, whereupon he remembered his magic word, transformed into Marvelman and saved the day almost as an afterthought before flying off proclaiming his return.

It was a little under a year before Warrior #1 debuted, and when it did, the introduction to Marvelman was practically unchanged from Moore’s spec script: the main plotlines and most of the details were in place before the artist was assigned. Skinn assigned another relative newcomer, Garry Leach, to draw the story, showing Leach the completed first script to persuade him to come on board. Leach did a lot of work redesigning the costume and thinking through the ‘look’ of the strip; he modelled Marvelman on Paul Newman and Liz Moran on Audrey Hepburn. Leach has said ‘Alan never objected to you pitching an idea in if it was relevant or enhanced the story’, and Moore was very happy to adopt some of the suggestions Leach had for improving the visuals – Marvelman acquired a glowing force field that allowed Leach to play with lighting effects, Leach had detailed thoughts on an early fight sequence, and he would call the writer whenever he felt he had other good ideas.

It’s fair to say Marvelman was less of a collaborative effort than V for Vendetta. This isn’t to diminish Leach’s contribution, but the idea of how to revamp Marvelman had been brewing in Moore’s mind for fifteen years, and the initial pitch document contained material that would carry the strip for over a year. Leach reorganised a few of the images, but left Moore’s captions and dialogue intact. There were only very minor changes: someone exclaims ‘Christ!’, when it’s ‘Jesus!’ in the script; a caption description of ‘cold granite’ dawn has become ‘cold grey’. Moore asked the artist to establish that the Morans didn’t wear anything in bed, and to ‘make it really casual and no big deal, so as to avoid that sort of faintly smelly Conan-type voyeurism’: Leach has a full-length image of Liz Moran naked, with her back to us. Overall, he does a superb job of bringing a complicated script to life, and squaring the circle of having a flying man in a sparkly leotard appear ‘realistic’.

The artist doubled up as art director for Warrior, so he worked in the same office as Skinn and they would discuss plot points, but there is no evidence of Moore having the same the lengthy back-and-forth discussions with Leach that he had with David Lloyd and many subsequent collaborators. Leach received a script every month, and when it arrived, ‘I’d brew up a coffee, sit back and have a damned good read because they were too dense to skim’.

The decision that the title for the mystery strip would be V for Vendetta concentrated Moore and Lloyd’s minds, as did the 10 July 1981 deadline all Warrior’s writers were set for #1 scripts. The main question became a simple one: what was the motivation for the character’s ‘vendetta’? Moore now decided that their hero was an escapee from a concentration camp out for revenge. But there remained the issue of what their protagonist looked like. Moore credits Lloyd for finding the solution: ‘The big breakthrough was Dave’s, much as it sickens me to admit it … this was the best idea I’d ever heard in my entire life.’ This was that Vendetta should be a ‘resurrected Guy Fawkes’. Lloyd included a sketch that’s identical to the final V, but with a pointy hat (though he also suggested, ‘let’s scrub V for Vendetta. Call the strip Good Guy.’) Lloyd’s notes also have the prescient comment that ‘we shouldn’t burn the chap every Nov 5th but celebrate his attempt to blow up Parliament … we’d be actually shaping public consciousness in a way in which some Conservative politicians might regard as subversive’.

Moore was enthusiastic: ‘There was something so British and so striking about that iconic image, and it played well into the kind of thinking that was already starting to develop on the strip.’ This was a reference to both Moore and Lloyd latching on to another Vincent Price movie in a similar vein to Phibes: Theatre of Blood (1973), which featured Price as a hammy Shakespearean actor who kills off a series of his critics.

In the same letter he suggested the Guy Fawkes look, Lloyd also explained that he wanted to avoid the use of thought balloons and sound effects captions. The idea terrified and excited Moore. Although not unprecedented, it was extremely unusual in mainstream comics and he suspected Lloyd had suggested it ‘almost as a joke, I don’t think he expected me to go along with it’.

Things moved rapidly from this point. V’s mannerisms now took on a more overtly theatrical, Jacobean flavour to match his Guy Fawkes appearance. Moore was able to make this more than a gimmick. In the first chapter, the mentality of the two sides in the battle is efficiently contrasted when a policeman concludes from the odd way V speaks that he ‘must be some kinda retard got out of a hospital’, failing to recognise that his opponent is quoting from Macbeth.

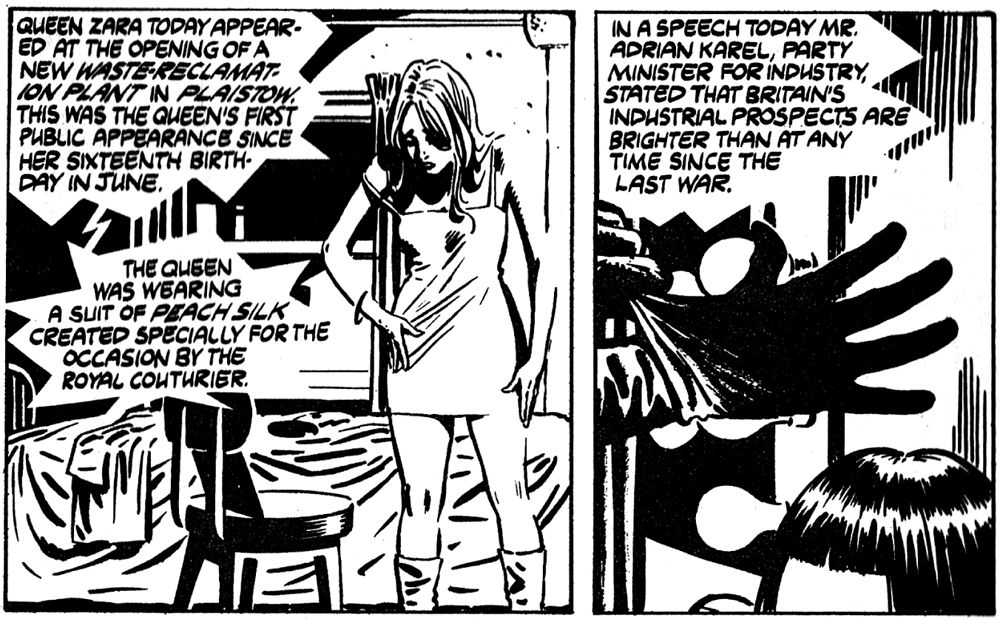

Moore and Lloyd had started out with a series about a vigilante fighting generic totalitarian forces, but the 1997 setting was not very far in the future and Moore had got there by extrapolating current headlines. While most British comics were set in imaginary places like Melchester, Northpool or Bunkerton, V for Vendetta was rooted in a Britain with real place names and even some real people. A telling detail is a one-off mention of Queen Zara in the first instalment – Zara Phillips was born in May 1981, only a few months after Amber Moore. As one letter to Warrior later noted, something catastrophic must have happened to the royal family if Princess Anne’s second child was now on the throne (Zara was sixth in line when she was born, tenth in the real 1997).

As Moore began drawing up a list of the fascist supporting characters, the various authority figures V was pursuing and the investigators sent after him, it made him look at the situation from their point of view. Whereas the ‘hero’ of the piece was a masked killer out for personal vengeance, the ‘bad guys’ were simply ordinary people doing what they believed was best for the country:

I didn’t want to just come into this as a self-confessed anarchist and say ‘right, here’s this anarchist: he’s the good guy; here are all those bad fascists: they’re the bad guys’. That’s trivial and insulting to the reader. I wanted to present some of the fascists as being ordinary, and in some instances even likeable, human beings. They weren’t just Nazi cartoons with monocles and University of Heidelberg duelling scars. They were people who’d made their choices for a reason. Sometimes that reason was cowardice, sometimes that reason was wanting to get on, sometimes it was a genuine belief in those principles.

All this could be read as a simple critique of the usual logic that there had to be goodies and baddies, and everyone was on one side or the other – an idea as prevalent in political discussion as in comic books. However, as Lloyd began interpreting Moore’s first few scripts and the finished product started to appear, they both came to realise they were creating something more sophisticated than they had planned.

Much of the credit can be put down to Lloyd. His most recent work, Golden Amazon and Doctor Who, had included painted wash effects and elaborate grey tones. On V for Vendetta, he chose an approach that was a visual joke: ‘David Lloyd was using this stark chiaroscuro style where you’d got no bordering outlines on the characters, you’ve got hard black up against hard white in the artwork. Whereas in the story, in the text, there was nothing but shades of grey in moral terms.’ The way characters merge into the shadows, the repeated panel compositions, use of close-ups, the intercutting with flashback scenes … all these make the reader work to see what is going on, encourage them to go back and re-read and reinterpret. Some panels almost resemble optical illusions that take a second or two to snap into place. An iconic early example occurs in the second chapter: there’s a panel of V standing on a railway bridge, his cloak flapping. Another character glances up and, like the reader, can’t quite work out what he’s looking at. This panel was later reproduced on house ads, badges and other promotional material.

It is in V for Vendetta that we see Moore’s first systematic use of what would become a trademark technique, exploiting one of the key strengths of the medium: the artistic effect to be gained by combining a picture and text.

A progression in comic art is evident here. In an unsophisticated early comic, the words would simply support or describe the picture: we might see an image of Superman with red lines coming out of his eyes that connect with a blob in the hand of a gangster and a caption saying ‘Superman melts the crook’s gun with his incredible heat vision!’ The Marvel comics of the sixties concentrated more on the inner life of their characters, revealing them to be troubled. Now we might see a picture of Spider-Man fighting Doctor Octopus, but a thought bubble saying something like ‘I hope I won’t be late for my date with Mary Jane’.

Comic art was now going beyond that, beginning to explore the far greater poetic effect to be had by using an image and text that seem to contradict each other or to have no obvious connection. It forces the reader to work out what link the creators might be implying. Moore was not the first comics creator to understand that this could add layers of meaning, as well as a degree of ambiguity, but his use of the technique has always been unusually sustained and sophisticated. Moore called it ‘ironic counterpoint’ in his first V for Vendetta script, and there is a good example on the second page of the first chapter.

The text is an announcement of ‘the Queen’s first public appearance since her sixteenth birthday’ where she wore a ‘suit of peach silk created specially for the occasion by the Royal Couturier’, while the picture is of a very young woman in a bedsit awkwardly putting on a dress. That contrast is obvious, but it’s the next page before we learn that this woman, like Queen Zara, is only sixteen years old. (It will be the third chapter before we learn the girl’s name is Evey Hammond and find out how her situation became so desperate.) The next panel juxtaposes that image of Evey in a dress that’s too small even for her slight frame with a close-up of V snapping on a glove. We’ll learn that both V and Evey are getting dressed to go out onto the London streets at night. Desperation has driven Evey to an ill-thought-through attempt to earn some money prostituting herself, whereas V will orchestrate an elaborate plan to destroy the Houses of Parliament. What Moore has understood is that the act of contrasting the words and images in one panel, then contrasting that panel with the next, creates patterns. The story can say two things, but mean a third, and the narrative can have a highly elaborate, allusive structure.

Without thought balloons giving convenient access to eloquent inner monologues of the characters, the dialogue Moore wrote and the faces Lloyd drew had to become more subtle and expressive. It was not only V who wore a mask – readers of V for Vendetta have to imagine what all the characters are thinking, and can never be certain what they really understand about those characters’ situations. A fascist government with bold slogans and fancy uniforms and equipment, the population under constant CCTV surveillance, individuals like Evey Hammond dolling themselves up – all of them are ‘putting on a brave face’.

There was yet another twist to standard conventions. While comics are full of masked figures, their masks are usually disguises. The readers are in on the secret identity of, say, Batman or Spider-Man. In a similar vein, the early instalments of V for Vendetta encourage the idea that we will eventually see the mask come off and learn that V has been one of the other characters all along – that there will be, in Moore’s words, ‘a satisfactory revelation’. This was a deliberate deception, and Lloyd says ‘we never had any intention of doing that’. The people who wrote letters to Warrior quickly came to a consensus that V would turn out to be Evey’s father, who she had not seen since he was dragged away by the authorities years before – few readers will have noticed that her father resembles Steve Moore, and like him, lived on Shooter’s Hill. When the series began in those early issues of Warrior, it was essential to keep the man under the mask an entirely mysterious figure, to the point that we can’t be entirely sure of V’s gender (while V is referred to as ‘the man in Room V’, some of the inmates were treated with hormones and changed sex).

Instead of pinning down who V is and what he really believes, the story is about piecing those things together. The other characters in the story are trying to, the reader has to. Because the narrative can’t look at V directly, we have to see him through the eyes of others. The story was presented in short chapters, and each had to remind the reader of where the story stood – but Moore and Lloyd had banned the use of lengthy captions, so they had to find a less direct way of recapping. By an alchemical combination of design, accident, genre expectation, form and the unintended consequences of storytelling choices, the result is that Moore and Lloyd tell the story as a series of vignettes. We are shown V’s world, often the same event or the consequences of that event, from a variety of viewpoints.

There is a main viewpoint character, though, and that’s Evey Hammond. She is not mentioned in the Warrior article, nor in any of the published notes or sketches, and Lloyd later stated that ‘the basic plot, and the characters involved, were all Alan’s, apart from Evey’. Lloyd also says, ‘she was a late addition to things … in Theatre of Blood, Vincent Price has a team of people helping him, and this was one of the ideas that Alan was bringing, so there was an idea that V would have an assistant that would help him in his sabotage, like the character Vulnavia in The Abominable Dr Phibes … that evolved into Evelina Falconbridge becoming Evey. It was a way of introducing Falconbridge, but not as an urban guerilla, just as this girl.’ It’s worth noting that the Falconbridge sample page features Evelina poised to save a woman from being raped by policemen, while the first chapter of V for Vendetta sees V saving Evey from the same fate.

Evey is not a major character at the start of the story. She becomes V’s accomplice in the murder of the corrupt Bishop of Westminster, but is little seen after that in Book One. V abandons her in the opening chapter of Book Two, then she drops out of the strip for several chapters, and it is only after she returns that she becomes a central character. Evey is immediately appealing and memorable – as well as one of very few women in the story – and it is not hard to infer that Moore was thinking of her when he told Bryan Talbot a few months later he had found ‘you can spin entire plotlines out of one supporting character if your character is strong enough’.

V for Vendetta was certainly a story that evolved as it was being told. In 1988, in his introduction to the first American edition, Moore acknowledged that the series changed under them while it was being written: ‘There are things that ring oddly in earlier episodes when judged in the light of the strip’s later development. I trust you’ll bear with us during any initial clumsiness and share our opinion that it was for the best to show the early episodes unrevised, warts and all, rather than go back and eradicate all trace of youthful creative inexperience.’ One element that emerged organically was one of the most memorable chapters in the story. It starts in Chapter 11 of Book One, as David Lloyd explains: ‘Alan had written a script with V in the Shadow Gallery and said “put him wherever you like”, and I put him in a private cinema. The one thing that bothered me at that point about V was that he had no real humanity to him. He was a guy in a mask. So I had him looking at pictures on a screen, and there’s this woman and you don’t know who she is. It might be a past love or a lost sister, you don’t know who they are. And you get this panel where he covers his eyes.’

In Chapter 11 of Book Two (first published in Warrior #25, December 1984), we learn that the woman was an actress, Valerie. She is a lesbian, and following the fascist coup, that was enough to have her sent to the concentration camp at Larkhill. She was in the cell next to V and passed him a note explaining her story, and that although she knows she will die, they have not broken her will.

The woman depicted on the screen was in fact an actress Lloyd knew at the time who’d sent him some pictures: ‘I wouldn’t dream of saying her name – I asked if she minded me using the photos and she was a big fan of V. And so I used those, and that led to the Valerie sequence, which for me is the core of the thing …’ As he admits, it was ‘an accident. And there’s a lot of accidents in V. The name is an accident, the Guy Fawkes thing was an accident … It’s perfect, but it’s an absolute accident.’

Lloyd concludes, ‘One of the great things that happens to me is that going to conventions, people come up to me and say the Valerie chapter changed their lives. And that’s a great thing, that you’ve not only created a great entertaining thriller, but it’s also meant something.’

What had started out as Dez Skinn simply trying to recreate Night-Raven was becoming something quite different. While V for Vendetta was grounded in the Britain of the early eighties, Moore and Lloyd started to realise as the story developed that ‘the strip was turning out all of these possibilities for things that hadn’t been there in the initial conception, but which we could then explore and exploit … it could be a love story, it could be a political drama, it could be, to some degree, a metaphysical tale. It could be all these things and still be a kind of pulp adventure, a kind of superhero strip, a kind of science fiction strip. And I think that we were just interested in letting it grow and seeing what it turned into without trying to trap it into any preconceived categories.’

With the first chapters of Marvelman and V for Vendetta completed, Skinn was very happy with Moore’s work. Moore was now more than a voice on the phone, he was visiting the Warrior offices and being encouraged to pitch more stories. Skinn explains, ‘We’d have regular monthly meetings. In part to up the ante. When artists saw what great work the others were doing I know that made them try harder! It was also to create a feeling of community. We all wanted the same things: more mature products and greater creative rights and freedom. Keeping everybody in the picture helped enable that.’

Moore used the opportunity to build up a list of contacts. Steve Parkhouse recalls: ‘When the first few issues were in preparation, I was visiting Dez Skinn’s editorial bullpit on a regular basis. On one occasion, I walked into Dez’s office to find a very large man with a very large beard looking at some of my artwork.’ This was the first time Parkhouse and Moore had met for ten years. Moore said it would be nice to work together on something, which Parkhouse assumed was the usual pleasantry. Shortly afterwards, he was surprised to be presented by Moore with ‘a choice of three different scenarios that he had been working on’. We know Parkhouse chose The Bojeffries Saga, and that he and Moore started work on the strip shortly after Warrior launched in early 1982. The three strips Moore developed once Warrior was underway signalled major interests that would recur in his later work.

The Bojeffries Saga was the first, and it appeared in Warrior #12–13 (1983) and #19–20 (1984). Parkhouse had been the writer and artist on one of the launch series in Warrior. Originally this was to be named Dragonsong, but it mutated into The Spiral Path. Although given carte blanche by Skinn, Parkhouse had found the result – a labyrinthine stream-of-consciousness fantasy story – deeply unenjoyable to create. With The Bojeffries Saga, ‘Alan made it very easy by delivering scripts of stunning innovation. We both knew exactly what was needed and almost by unspoken agreement we didn’t interfere with each other’s processes.’

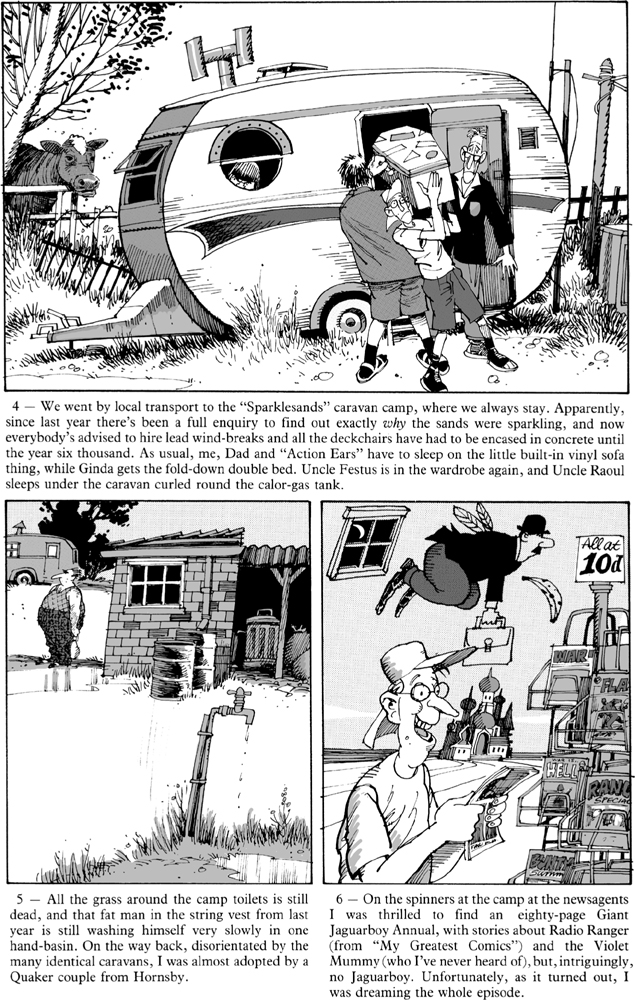

Formally, The Bojeffries Saga is a rather straightforward, even old-fashioned strip, with large panels telling a linear story. It even has the dreaded thought balloons. Moore described the series as taking place ‘in an unnamed urban mass – possibly Birmingham, possibly Northampton’, but he was consciously trying to tie it back to his upbringing. As he said in 1986: ‘Me and the artist Steve Parkhouse have been trying to get the feel of the really stupid bits of England we can remember from when we were kids … we boiled all this down into a fantasy on the English landscape in which we set these various werewolves and mutants. In a funny way it’s a lot more personal than a lot of the strips I’ve done.’ Twenty years on, he stressed the same point: ‘Bojeffries was important in that it was one of the personal things that I’ve done … it looks very surrealistic to Americans, whereas, to me, it’s a thing that I’ve done that I’ve come closest to actually describing the flavour of an ordinary working-class childhood in Northampton.’ In some places The Bojeffries Saga is simply Alan Moore’s childhood with the names changed and slight exaggeration for comic effect.

Although it’s deeply personal, the strip has perennially been overlooked. Partly this is because it’s been difficult to find: it took some years for the series to be collected for the American market (as The Complete Bojeffries Saga, Tundra Press, 1992, an edition that is harder to track down than the original Warriors). That cannot be the only reason for its neglect, though, as Marvelman has been even harder to come by and that has only served to inflate its status. Many readers who lapped up Marvelman and V for Vendetta, particularly in America, have a very hard time ‘getting’ the strip in the other sense of the word: it seems difficult to categorise generally and as part of Moore’s oeuvre in particular.

The main reason is simple: The Bojeffries Saga is a comedy.

In 1986, Moore described The Bojeffries Saga as ‘one of the few comedy strips I’ve done’, but from his earliest work onwards, he has written out-and-out comedy whenever he has had the opportunity. At the time he was starting work on Warrior, he was writing and drawing weekly instalments of The Stars My Degradation and Maxwell the Magic Cat. He had written the first Abelard Snazz script as a Future Shock for 2000AD, and that would become a short series. All the Future Shocks and Time Twisters, not just those written by Moore, were meant as light relief. Moore’s best-known comedy series, DR & Quinch, started as out as a one-off Time Twister (‘DR & Quinch Have Fun on Earth’, 2000AD #317, May 1983). The Bojeffries Saga, then, was part of a continuing and major strand of Moore’s work, not some aberration or slight side project.

Neither, though, was it an obvious fit for any British magazine. While it has werewolves and vampires in it, it’s not a horror strip. It’s not the sort of science fantasy 2000AD might print. One correspondent to Warrior summed up a common reaction in the letters column in #16: ‘I liked this story but it was out of place in Warrior.’ The Bojeffries Saga was featured on the cover of its debut issue, with the strapline: ‘Makes Monty Python Look Like A Comedy … a soap opera of the paranormal’. This was more confusing than accurately descriptive, as it’s not all that Pythonesque, (although Michael Palin would have made an excellent Trevor Inchmale, the Walter Mittyish rent collector who’s the viewpoint character of the first story.) In fact, with a family of supernatural creatures living in a typical home, there is a superficial resemblance to the American TV series The Addams Family and The Munsters (a comparison Moore and Parkhouse have resisted). But The Bojeffries Saga is perhaps most like The Young Ones, a TV sitcom about a houseful of unappealing students which debuted on BBC2 in late 1982 and was invariably described as ‘anarchic humour’. That show was one of the first flowerings of eighties alternative comedy on television, so it was fitting that the Tundra reprint of the series featured a foreword by alternative comedian (and comics fan) Lenny Henry.

It is more productive to analyse where The Bojeffries Saga fits in Moore’s development as a writer. The real reason it was in Warrior is that Dez Skinn trusted Moore and Parkhouse, and he knew that his readers were keen on Moore. It’s fair to say that The Bojeffries Saga was the first strip published because the writer is Alan Moore.

Moore would moreover agree with Steve Parkhouse’s assessment that ‘we never realised its full potential’. Four instalments appeared in Warrior, another six would show up in various places over the next ten years. Whereas Moore sees his other Warrior strips as done and dusted, he has shown interest in reviving The Bojeffries Saga, and for many years Top Shelf, his American publisher of choice, have listed a collected edition with new material as ‘forthcoming’. It’s an early series, but one that fits quite comfortably with Alan Moore’s current work.

Warrior #9 and #10 (January/May 1983) saw the appearance of the second of the three ideas Moore had pitched to Dez Skinn. Moore and Garry Leach’s Warpsmith was a straight science-fiction strip based on characters Moore had first devised back in his Arts Lab days. One of the Warpsmiths, an alien police force, had appeared on the cover of Warrior #4 and in that month’s Marvelman strip readers learned that the Warpsmiths would become key allies of Marvelman. In their own strip, we learn that the Warpsmiths are a race of teleporters, one whose language doesn’t even have a word for ‘distance’ because they can travel anywhere instantly. The story portrays a number of groups of aliens, all with their own distinctive jargon. It is a high-concept, grown-up science fiction idea, but it’s not rooted in the ‘realistic Britain’ Moore was basing his other Warrior strips around, and the strip did not return to the magazine. Warpsmith went on to feature in A1 (1989), an anthology title that Garry Leach would publish (the characters were the cover stars of the first issue) and played an important part in the last book of Marvelman. If Warpsmith had caught on, no doubt it would have become a soaring science fiction epic with a distinct identity. As it stands, the series is probably best considered a spin-off from Marvelman.

Moore ended up taking his third idea, Nightjar, to Bryan Talbot, a writer/artist who had been part of the Birmingham Arts Lab and had an extensive background in underground comics, but was now looking for more mainstream work. After drawing a single illustration of Adam Ant for a magazine he found, somewhat to his bemusement, that he had been ‘branded as “the Adam Ant artist” and spent most of a year producing pics and logos for various Ant publications’. Comics connoisseurs knew Talbot as the creator of the extraordinary The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, a sexy, intricate epic about a war fought across parallel universes. This had begun in 1978 in Near Myths, an Edinburgh magazine that also featured some of the earliest work by future comics superstar Grant Morrison. Near Myths, though, only ran for five issues. As Moore and Talbot started working together on Nightjar, pssst!, the magazine that had rejected David Lloyd’s Falconbridge, had just agreed to reprint and continue Luther Arkwright (starting from #2, February 1982) and Moore’s initial letter to Talbot congratulated him for that.

The letter seems to have been written just after the launch of Warrior. Moore had thought about Talbot’s strengths as an artist – his use of white space, his ‘sense of Englishness’ and familiarity with art beyond the world of comic books – and sensed a kindred spirit, because of a shared background in underground comics. The strip they were to collaborate on was to serve two purposes. First (as we might guess by now), ‘I’d like a very believable and realistic 1982 setting’. This would involve a portrayal of magic that was ‘more low-key and less pyrotechnic … I’d like to suggest a sort of magic reality by the use of coincidences and shit like that’. Moore was interested in featuring working-class magicians. Second, he envisaged ‘a vehicle for semi-experimental storytelling devices … I should imagine from the episodes of Arkwright that I’ve seen this is pretty dear to your heart as well’. He said he wanted to emulate Eraserhead, Nic Roeg and Kubrick.

Moore had a clear advantage over Talbot in his experience of what the readers of Warrior, and perhaps more pertinently its editor, would want. He told Talbot that Warrior was for ‘a 12 to 25-year-old audience’, and saw it as important that a series with a female lead should ‘educate some of the pre-teen misogynists in our audience about what women are like’. He wanted their protagonist to be unconventionally attractive, though conceded that ‘we do have to appeal to people with base sensibilities. Dez for one, 40,000 readers for another.’ Indeed, Skinn’s pragmatism looms large: Moore advises Talbot that his editor will want a ‘broad commercial approach’ and an instantly recognisable lead character, and art that can easily be coloured for foreign editions; he suggests they plan for three episodes and then assess ‘the Dez/reader reaction’. Moore visited Talbot for a couple of days at home in Lancashire before starting the script and they discussed the concept in more detail.

The results can be seen in the first instalment, which efficiently sets up the premise. Harold Demdyke (‘he looks like everybody’s dad after Sunday dinner’) dies in front of his young daughter, Mirrigan. Years later, her grandmother announces that he was ‘Emperor of All the Birds’, the most powerful of sorcerers, and that he died at the hands of seven other magicians. Mirrigan is to kill them and take the title for herself. We see the seven antagonists, including the current Emperor of the Birds, the MP Sir Eric Blason (‘this guy is about power on a level that drug-addled ninnies like you and I can scarcely conceive’, Moore tells Talbot). In the letters column of Warrior #8 (December 1982), Skinn was able to announce that ‘Bryan Talbot is working on a contemporary sorceress strip from an Alan Moore script’.

But by then the project was clearly on the back burner for writer, artist and editor alike. Skinn admits, ‘I was never very keen on Nightjar (hated the name) and Bryan was another slow – or busy – artist, so it would never have happened in Warrior which had to hit deadlines or there’d be no money in the kitty to pay contributors.’ By the time Warrior folded three years later, Talbot had completed just two and a half pages of the eight scripted and pencilled one other. He simply got a better offer: Pat Mills had approached him to replace Kevin O’Neill as the regular artist on 2000AD’s Nemesis the Warlock. He would follow that with stints on Slaine and Judge Dredd that would keep him occupied for the next four years (it’s worth comparing Talbot’s progress on Nightjar with the five or six pages a week he was completing for 2000AD).

Talbot’s first work for 2000AD had been a short strip written by Moore (‘Wages of Sin’, #257, March 1982), and they would soon work together on ‘Old Red Eyes Is Back’ (a Ro-Busters story for 2000AD Annual 1983, August 1982), but Talbot hasn’t drawn another Moore strip. They did work together on a video project, Ragnarok (1983). In the late eighties Talbot completed The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, with Moore writing the foreword to the second volume of the collected edition in December 1987 (‘he created a seamless whole, a work ambitious in both scope and complexity that still stands unique upon the comics landscape’). Talbot became a semi-regular artist for DC Comics in America, his most high-profile work being on Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman. From there, he returned to original graphic novels that he both wrote and drew, cementing his reputation as one of the most important and interesting British creators – The Tale of One Bad Rat (1995), Heart of Empire (1999, the sequel to Luther Arkwright), Alice in Sunderland (2007), Grandville and its sequels (2009–), and Dotter of Her Father’s Eye (2012). In 2003, William Christensen, editor-in-chief of Avatar Press, contacted Talbot about Nightjar, and Talbot was surprised to find he still had the script and pages. Avatar commissioned him to finish the first chapter, then reprinted it along with the script, the initial notes and an essay by Talbot in Yuggoth Cultures, a series dedicated to Alan Moore rarities.

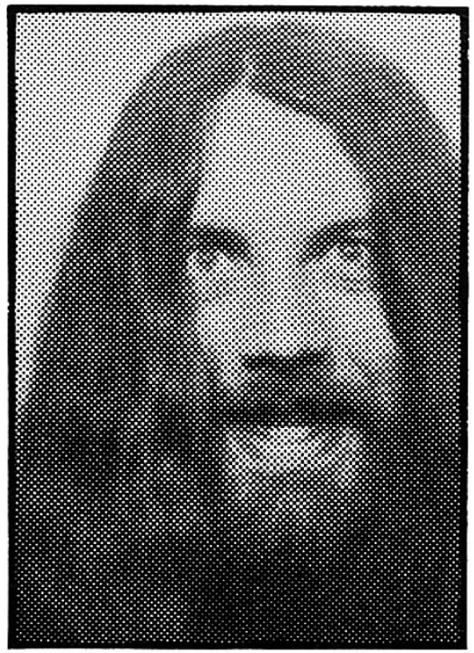

Warrior #1 appeared in newsagents in March 1982, and featured the opening instalments of Marvelman and V for Vendetta, Steve Parkhouse’s Spiral Path, and four strips written by Steve Moore: Prester John, Father Shandor, Laser Eraser & Pressbutton and A True Story (a one-off with art by Dave Gibbons). The last two pages of the magazine were dedicated to short biographies and pictures of the contributors. Alan Moore is represented by a photograph that makes him look particularly demented (see opposite page) and a profile, clearly written by Moore himself, which gave a short recap of his career to date, including the work of his pseudonyms, Curt Vile, Jill de Ray and Translucia Baboon – the latter being an identity adopted by Moore for the early eighties relaunch of The Sinister Ducks.

The second issue contained the same regular strips, with the addition of Paul Neary’s The Madman. It had a Marvelman cover and a text feature on Axel Pressbutton with contributions from Moore as Curt Vile. It also included its first letters column. The letters pages of Warrior were a vital part of the reading experience. As he had in his fanzine days, Skinn published correspondents’ full addresses, allowing comics fans to get in touch with each other directly. And the creators of the individual strips often replied directly to a specific point raised: in #6 (October 1982) Moore asked one reader who complained about the use of ‘Christ’ as an expletive why he hadn’t complained about all the violence. It is clear that the readers, at least those who wrote letters, were keen on Pressbutton, Marvelman and V in roughly equal measure, and less keen on the other stories. For his part, Skinn ‘always thought of V as a sleeper hit, like the album track which only grows on you slowly, off the back of more commercial tracks. So I very much saw Marvelman and Axel as our frontrunners.’

The first three issues of Warrior came out on time and to plan but did not sell as well as hoped, with Skinn later noting ‘if I’d been an accountant, I’d have … cancelled the magazine when I saw the returns on issue one’. While 2000AD was selling ‘a rock solid 120,000 copies a week’, sales of Warrior fluctuated but it had a reported print run of around 40,000 and, although it failed to make much of a stir across the Atlantic at first, it sold better than expected in America, with US sales accounting for a quarter of the total. Nevertheless, money was tight. Garry Leach said of his position as Warrior’s art director: ‘That sounds pretty glamorous and high powered, doesn’t it? Quality Communications ran from a sleazy little basement beneath a seedy comic shop in New Cross; a rundown low-life area just outside central London. It was festering and alarmingly cheap – which would sum up the entire operation! … Dez always had about two thousand reasons why he couldn’t pay you that week.’ It is a description which makes the ‘revolutionary’ Warrior sound remarkably like the old IPC as described by Steve Parkhouse.

Alan Moore was soon getting plenty of regular work beyond Warrior, but Dez Skinn was an editor who encouraged him. Moore was being noticed by Warrior’s readers – he was often singled out for praise by letter writers – and he retained ownership of the characters he created (he was granted part-ownership of Marvelman). Moore was learning, with V for Vendetta particularly, that the comics medium was an alchemic one, where the finished product was more than the sum of the writing and art, and that a running series could progress, adding layers of meaning and resonance.

In late August 1982, around the time Warrior #5 was published, Moore wrote to Skinn with suggestions for spin-off series. Vignettes would be set in the London of V for Vendetta but would tell ‘little Eisneresque stories about ordinary people living in a very tough world’. Untold Tales of the Marvelman Family would build on the backstory of that series, with Moore suggesting ‘we could do a story about Gargunza … maybe one describing how he came to build the FATE computer’ (FATE was the all-seeing computer from V for Vendetta, Gargunza the evil scientist who created Marvelman). At this point, Moore saw the two strips as linked, and he and Steve Moore had come up with an elaborate future history that saw ‘the Warpsmith takeover of Earth, the Rebellion against the Warpsmiths and their subsequent destruction, the Golden Age of Earth, the Superhero purges, the Exodus of the Marvelmen, the war between FATE and the Rhordru Makers, and so on and so on’. The story continued, in fact, beyond the far future seen in Pressbutton.

Only a year or so before, Alan Moore’s declaration of intent in the Society of Strip Illustration round table had seemed over-ambitious and a little naïve, but he had already achieved many of those goals. Moore’s ‘greatest personal hope’, writing a revamped Marvelman, had proved to be the quickest and easiest part of it.