‘There’s nowhere to go in this country… no space. Not like in America, that’s what it’s really like to be on the road. THE road is in America.’

Kid, Another Suburban Romance

Swamp Thing inhabits a murky backwater of the DC universe, on his own far from the soaring towers of Superman’s Metropolis or Batman’s Gotham City. This was also the status of the comic book The Saga of the Swamp Thing in DC’s 1983 line-up. The character had been created in 1971 by Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson for a one-off appearance in House of Secrets #92 (1971), which had led to a short-lived Swamp Thing comic (twenty-four issues from 1972 to 1976). The movie rights were optioned in 1979 and the resultant movie, directed by Wes Craven, was released in March 1982, whereupon DC revived the comic to cash in. Alan Moore was contacted a little over a year later, and as he later summarised, ‘I was given this book called Swamp Thing which was really the pits of the industry. At the time it was just on the verge of cancellation, selling 17,000 copies and you can’t do comics beneath that level.’

Swamp Thing’s protagonist was Alec Holland, a scientist who had been caught in an explosion and stumbled out of his laboratory engulfed in flame, then fallen into the neighbouring swamp and sunk into the murky waters, where his flesh transformed into vegetation. Swamp Thing stories concerned Holland’s attempts to restore his body to human form while protecting people from other monsters and supernatural creatures. Moore knew, ‘It was a dopey premise. The whole thing that the book hinged upon was there was this tragic individual who is basically like Hamlet covered in snot. He just walks around feeling sorry for himself. That’s understandable, I mean I would too, but everybody knows that his quest to regain his lost humanity, that’s never going to happen. Because as soon as he does that, the book finishes.’

The Saga of the Swamp Thing was one of a very few non-superhero books published by DC, the only remaining horror comic in its line-up (the venerable House of Mystery had been cancelled after 321 issues in October 1983). There had been horror comics since at least the fifties, when EC Comics set the standard for short tales with a nasty twist. A moral panic about the role of comics in inspiring juvenile delinquency had led to the introduction of the Comics Code Authority (CCA) in 1954. This saw the comics industry self-regulating by agreeing to abide by a draconian set of guidelines. Even after the Code was revised in 1971 to relax many of the restrictions it still decreed, among many other things:

1. No comic magazine should use the word ‘horror’ or ‘terror’ in the title …

2. All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.

3. All lurid, unsavoury, gruesome illustration shall be eliminated.

…

5. Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead or torture shall not be used. Vampires, ghouls and werewolves shall be permitted to be used when handled in the classic tradition such as Frankenstein, Dracula and other high-calibre literary works written by Edgar Allen Poe, Saki (H.H. Munro), Conan Doyle and other respected authors whose works are read in schools throughout the world.

Although the code would be revised again in 1989, these were the standards a horror comic published in 1984 still had to follow. The production of horror comics continued, but under the aegis of the CCA the genre had been neutered and only ever traded in the same sort of tame trick-or-treat imagery as Scooby Doo.

It so happened that Alan Moore would have been perfectly suited to write EC-style stories. Thanks to his long interest in comics, he was very familiar with the original material. When Steve Moore came up with the Future Shocks format for 2000AD, it had owed a clear debt to those old EC stories, and Alan had mastered the form. There’s no indication, though, that Len Wein even knew about that part of Alan Moore’s CV. What interested him was Moore’s skilful revamping and reinvention of characters like Marvelman and Captain Britain. Wein sent Moore a set of recent Swamp Thing issues, and Moore drew up a fifteen-page document explaining what he thought the problems with the character were and how they might be addressed.

Moore decided that the key was to make it work as a ‘horror comic’ fit for the early eighties. There is no evidence he was an avid fan of the horror genre at the time, although he had read Dennis Wheatley and H.P. Lovecraft as a teenager. Steve Moore was however an aficionado, and a contributor to the Dez Skinn-edited House of Hammer, which had been running (under a number of variant titles and two publishers) since 1976. That magazine featured comic strips by artists like John Bolton and Brian Bolland, which might have piqued Alan’s interest. He would have been aware that in the late seventies a new style of horror novel had emerged, exemplified by the work of writers like Stephen King, Clive Barker and Ramsey Campbell. Nor was the trend just a literary movement; in interviews, Moore contrasted the tame ‘horror comics’ of the time with movies like Alien, Poltergeist and John Carpenter’s The Thing – ‘I’m very conscious that we’re competing for kids’ money with video, with films, and with Stephen King books – not with Tomb of Dracula or Werewolf by Night.’ As with his Warrior work, the key was to ground the story in reality. It was a lesson learned from King, whose books had all the shocks and twists the genre demanded, located in a defamiliarised small-town America:

We’re going to try and actually focus upon the reality of American horror and see if we’ve got some good material there to turn horror comics out of … I tend to think that the horror that existed in the forties with the Universal films, it’s played out, it’s a different audience now. I mean what frightens people these days is not the idea of a werewolf jumping out at them, it’s the idea of a nuclear war or any of the sort of things that we have coursing through our society at the moment. I think that to really frighten people, you have to somehow ground the horror in their own experience, things that they’re frightened of.

Moore felt it was important to return Swamp Thing to his swamp, and took pains to emphasise the setting, although he never visited Louisiana and his method of establishing a sense of location was to buy maps and guidebooks. Someone sent him a copy of a phone directory from the state so that the names in the stories sounded local.

His artists were to be Stephen Bissette and John Totleben, two friends who had joined the book shortly before Moore, with #16 (August 1983). Swamp Thing had long been Totleben’s ‘all-time favourite comic book character’, but neither artist was keen on the direction the previous writer, Marty Pasko, had taken (Pasko later reported that he had been annoyed to receive story suggestions from them). The artists were fans of Warrior, and delighted to learn Moore would be their new writer. He sent them a four-page letter outlining his plans and inviting their contributions. Straight away, it was clear that writer and artists were on the same wavelength. Unlike Moore, Bissette was an avid horror fan and keen to make the book genuinely scary. They all agreed that the protagonist had to change his appearance. Swamp Thing had been depicted merely as a large, hunched man with green skin and some roots that looked like the veins of bulging muscles. He was redesigned to emphasise, particularly in close up, that he was a mass of moss, mud and living plants, with leaves, twigs, buds, roots, shoots and even flowers protruding from him. Bissette and Totleben found that Moore would eagerly adopt their ideas for individual visual sequences or character designs, while he had a strong sense of the ‘whole network’, the direction of the running stories.

Moore faced the same problem he had dealt with when taking over Captain Britain: he had been handed an existing series – not just one with a ‘dopey premise’, but with nineteen previous issues of accumulated story and supporting cast that he was simply not interested in. He solved it the same way: with a swift cull of the characters he didn’t think were working … and, as with Captain Britain, that included the protagonist. Alan Moore’s first issue of The Saga of the Swamp Thing ends with Swamp Thing shot through the head and killed.

Moore’s vision for the series really kicks in with #21, The Anatomy Lesson (February 1984). An autopsy is performed on Swamp Thing, during which the very idea that a human can be ‘turned into a plant’ is mocked as scientifically illiterate. Swamp Thing’s ‘brain’ and ‘lungs’ and so on are functionally useless vegetable structures that only physically resemble human organs. The pathologist deduces that this wasn’t Alec Holland’s body, that the man had died in the swamp, his memories somehow being imprinted on the plant life there. While it may seem like an obscure or minor change, the entire premise of the series to that point had been that Holland was on a quest to convert himself back to flesh and blood. Now it transpired that Swamp Thing had never been Alec Holland. If – it’s a big if – Swamp Thing really is ‘Hamlet covered in snot’, then the equivalent would be for Act Two to end with Old Hamlet showing up alive and well and wondering why his son is moping around so much. The doctor’s second conclusion is a punchline delivered with perfect timing: ‘You can’t kill a vegetable by shooting it in the head’. Swamp Thing revives, learns its true nature and, in an inhuman rage, kills the man who captured it. As Warren Ellis, then an eager regular reader of Warrior, soon to be an acclaimed British writer of American comics, would put it:

This story was the first hand grenade thrown by what you might call the British sensibility in American comics. In using the surgeon’s monologue as narration, it avoids all the purple prose that otherwise characterises much of the early British work in American comics (including some of Alan’s own). Miracleman predates it, but this was the first time a wide audience in modern comics had been shown a character they knew well, and told that everything they knew was wrong. Now, it’s a cliché. Then, it was explosive.

Structurally, it’s untouchable. Perfectly paced, a complete short story, powered by hate and Moore’s sudden grasp of the possibility in the 24-page form. As a British writer, he’d been restricted to the 6 to 8-page form before now. It was like seeing a clever piccolo player suddenly get access to an orchestra.

Horror fans would gradually learn about Moore’s work on Swamp Thing, and he would manage the virtually unheard-of task of persuading older readers who were fresh to comics to buy a monthly ongoing series. Early on, though, Moore understood he needed to entice existing comics fans. He made a calculated attempt to locate the series in the wider DC Universe. An early story showed the Justice League of America – the team that includes all DC’s big names like Batman, Wonder Woman and Green Arrow – watching helplessly as the plant life of the Earth rebels, then demonstrating how Swamp Thing can fight that threat in a way that Superman and Green Lantern can’t. His stories were set in the same fictional space as all the DC superhero comics, but would be covering different territory. That point made, Moore would bring in as guest stars a large number of existing DC ‘supernatural’ characters, like the Demon, the Spectre, Dr Fate, Zatara and the Phantom Stranger. Some were well-known and were appearing in other comics at the time, like the magician Zatanna, a member of the Justice League; others, such as the minor demons Abnegazar, Rath and Ghast, were obscure to all but the most obsessive fan. Moore set about integrating the disparate characters, created over six decades by many different writers and artists, into a broadly consistent narrative framework.

Editors at DC were astonished by what Moore, Bissette and Totleben had managed to make out of such unpromising material. An editorial that ran across all DC comics in late 1984, ‘Spotlight on … Swamp Thing’, declared that ‘if any book could be called a sleeper or, in this case, a buried treasure, it’s The Saga of the Swamp Thing’. Bissette talked about the nature of the support DC were giving them: ‘Being more positive about the work. Letting Alan, John and me have this exchange of energy and letting it pretty much go. We’re free to work with each other and work these things out, and we’re pretty much trusted with what we’re doing. Plus, they’re putting the PR machine behind us now. We’re going to be doing some ads. They’re doing a new DC Sampler this year, that free comic with just double page ads for all their characters, and they gave us the centre spread which is a pretty choice position. So they’re really starting to showcase Swamp Thing.’ Another piece of evidence that the title was starting to make waves was that Bissette made those comments in The Comics Journal #93 (September 1984), the ‘Swamp Thing Issue!’ with a painted cover by himself and Totleben, and long interviews with the team. By the end of 1984, the efforts of the new team had led to a sales increase of about 50 per cent.

Len Wein met Moore when he visited England in early 1984. Wein was soon to move on, though, and Moore gained a new editor, Karen Berger, from #25 (June 1984). If anything, this proved to be an even more fruitful partnership. To Moore’s eternal delight, Berger defended his corner when Swamp Thing #29 (October 1984) fell foul of the CCA. As he explained when interviewed in 1986 by a young journalist called Neil Gaiman:

For anyone who doesn’t know what the Comics Code is, back in the Fifties, when America was in the throes of all kinds of witch hunts, a man called Frederick [sic] Wertham produced a book called The Seduction of the Innocents [sic]. He said that disturbed kids he had treated had all read comics at some time or another – he could probably have drawn the same conclusions about milk. He printed panels from comics out of context: one, for example, showed a tight close-up of Batman’s armpit, so it’s just a triangle of darkness – Wertham managed to imply that this was a secret picture of a vulva the artist had put in to titillate his younger readers. Reading Batman must have been an endlessly enriching erotic experience for Wertham … I mean, if you can get that much out of an armpit! Well … As a result of the book, the comic’s publishers imposed a code of practice on themselves.

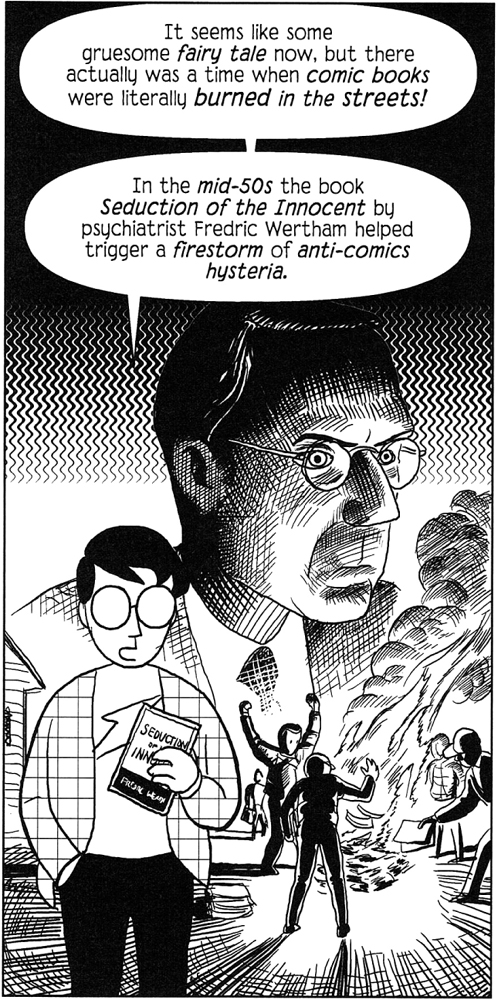

Moore’s generation of fans grew up regarding Frederic Wertham as the comics industry’s equivalent of Joe McCarthy and the Comics Code Authority as akin to the Hollywood Blacklist. Seduction of the Innocent had roughly the same connotations as Mein Kampf. This is not an exaggeration: comics historian Mark Evanier has described Wertham as ‘the Josef Mengele of funnybooks’; comics publisher Cat Yronwode claimed ‘probably the single individual most responsible for causing comic books to be so reviled in America is our good friend and nemesis Dr Fredric Wertham … We hate him, despise him … he and he alone virtually brought about the collapse of the comic book industry during the 1950s.’ The normally level-headed comics scholar Scott McCloud depicts Wertham as an almost demonic, bookburning figure (see right).

The spectre of a return to those dark days hung over the industry for decades, along with the nagging fear that any attempt to produce a comic an adult might be interested in would somehow fall foul of authority.

There are huge problems with this version of events, particularly with the depiction of Wertham, a non-practising Jew who had fled Nazi Germany and who was ahead of his time in raising issues like media depictions of the female body and racial stereotyping. An article he wrote criticising segregation in American schools was cited in Brown v Board of Education, the 1954 landmark case that found the practice unconstitutional. He was no foam-mouthed anti-comics zealot: his last book, The World of Fanzines (1973) praised the imagination and expertise of fandom, seeing the creativity and active engagement of the participants as a model for young people.

That said, there’s clearly some truth in the ‘standard account’ of the Seduction of the Innocent affair. The whole subject of censorship is complex and eternally sensitive, but we can generalise that freedom of speech is a good thing and that the urge to ban books is a bad thing. There was a moral panic in the mid-fifties around comic books and juvenile delinquency, and at its heart was an absurd confusion of correlation and causation: most teenage hoodlums had indeed read comics as children, but only because at the time 90 per cent of all children did. Articles by Wertham reached huge general audiences in Reader’s Digest, Collier’s and Ladies’ Home Journal. There were two Senate Sub-committee hearings run by Democratic Senator Estes Kefauver, an ambitious politician looking to pick opportunistic fights on ‘values’ issues. The Comics Code was established as a result and it did become all but impossible to sell crime or horror comics.

There were those in the comics industry who asserted that the Comics Code Authority stifled the industry’s creativity and it was therefore the prime reason the medium remained in a state of arrested adolescence. This reeks a little of scapegoating though. The CCA was not a vast government agency: in the early eighties it consisted of a man called J. Dudley Waldner and his wife. With hundreds of comics published every month, they could not carefully scrutinise every word and line. As Dick Giordano, vice-president of DC Comics, explained in 1987: ‘The two of them read the same things differently, because there are no real standards. It’s basically how they feel on that given day. So, for example, and this is what caused us to take Swamp Thing from the Code, one part of a two-part story that had bodies in it and flies flying around in it was approved, the second part of the two-part story which had the same elements in it was disapproved, simply because it had been read by two different people.’

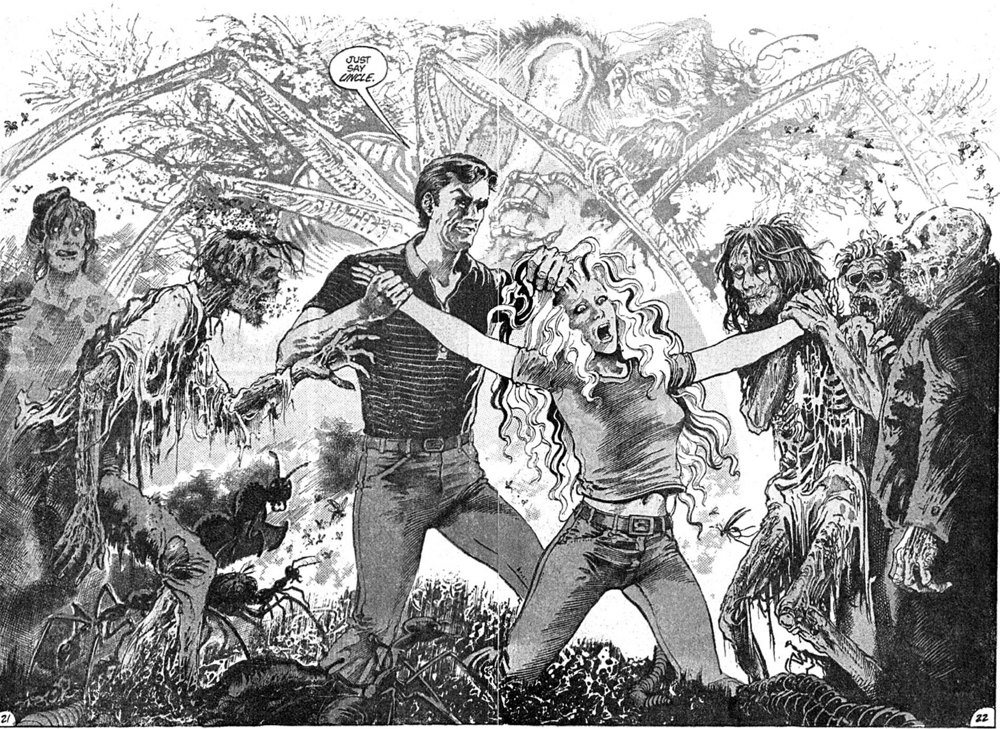

What tipped them off was this double spread at the end of The Saga of Swamp Thing #29:

Once alerted, they went back and read the issue more carefully. The zombies in question were moving because their insides were masses of insects, which is pretty unpleasant. The real problem, though, was that the story involves the female lead, Abby Cable, learning that her husband Matt has been possessed by the spirit of the series’ arch-villain, Arcane. A casual glance at the comic would lead the reader to think that Abby was traumatised by that simple fact. A more careful reading would reveal that Arcane is Abby’s uncle, that Abby and Matt have recently slept together, and so the story is about a woman suffering a sexually abusive, incestuous relationship.

DC – initially in the form of Berger, then her boss Giordano – stood by the story, and took the almost unprecedented step of publishing it without Code approval. Swamp Thing #29 appeared in comic shops and on news-stands alongside the other DC titles. When asked how he felt about that, Moore savoured his victory, answering, ‘Well, given the insufferable size of my ego, what do you think I think of it? It’s something that gives me immense pleasure and an overwhelming feeling of smugness every time it crosses my mind.’

From #31, the decision was made to publish The Saga of the Swamp Thing without Code approval. Moore, Bissette and Totleben didn’t look back. The series became a venue for crawling body horror and disturbing images, yoked to a political consciousness that, while mostly shared by Bissette and Totleben, was distinctly Alan Moore’s worldview. Swamp Thing became a champion of environmentalism, but that is a description that sells the content short. Moore and his artists did not adopt a simplistic approach to the material: it was difficult, personal work. As Douglas Rushkoff put it,

Swamp Thing was an ideal conduit for Moore’s memes … Swamp Thing is totally dependent on the condition of his environment, but maybe, as the comic implies, so are the rest of us who are just as dependent on the plant kingdom for food, air and a balanced biosphere. The psychedelic agenda is presented in equally bold strokes. Many psychedelic users believe that the drugs function by giving human beings access to ‘plant consciousness’ … in Alan Moore’s hands Swamp Thing became a media virus to promote this pro-psychedelic, pro-plant kingdom agenda.

Swamp Thing #34 featured ‘The Rite of Spring’, the consummation of Swamp Thing’s relationship with Abby. She ingests a tuber she plucks from his body, and goes on an LSD trip where they form a perfect, orgasmic union. In the American Gothic sequence (beginning with #37, June 1985), Swamp Thing began touring America, fighting supernatural creatures who symbolised the rot Moore saw affecting the country: racism, misogyny, gun violence, corporate pollution, the nuclear industry.

Not everything in the garden was rosy, however. Stephen Bissette would later confess: ‘I hated the intrusion of superheroes into the pages of Swamp Thing (and said so, apparently with enough vigor for Len to tell me it was his idea, a white lie told to me so I wouldn’t direct my ire at Alan, who was the real catalyst for the coming of the Justice League into Swamp Thing with #24), and even having bucked and shucked the Comics Code with SOTST #29, we were still working under mainstream comics restrictions. That forced us to be inventive with our subversion, but the necessary (to my mind, essential) evolution of horror comics required something more radical and unfettered.’

As ever, one of the more prosaic restrictions of a monthly comic was the necessity to work to a rigid timetable. Moore could write a comics script quickly, but now he was being called on to do so quite frequently. Swamp Thing #19 was already complete and heading to the printers when he was commissioned for #20. Various other production bottlenecks meant that, for example, the script for #29 had to be written in three days, that the ‘inventory’ issue he wrote to be used as a fill-in for use in an emergency was used immediately (#32), and that Moore had to come up with a way to dress up a reprint of the first Swamp Thing story with a new framing sequence (#33).

The biggest problem was that Swamp Thing was subject to what senior DC figure Paul Levitz once called ‘the worst contract DC has ever made’. In the early eighties, the company led the way in improving the deal for creators. Previously – and at Marvel, this was still the case for many years afterwards – the publisher could turn, say, a cover illustration into a poster or T-shirt without any further payment to the artist. That had changed under DC’s new president, Jenette Kahn (appointed in 1981), and now creators received a cut of the revenue from any exploitation of characters they created or artwork they had drawn. One exception, though, was Swamp Thing. The 1979 movie option included the right to use any or all of the characters and situations created for the series, as well as the merchandising rights. The main practical effect was that DC could not market posters or T-shirts based on Bissette and Totleben’s art, or any of the toys or badges that other DC characters enjoyed, let alone pass on a share to the creators.

Even so, working for DC was lucrative for Moore. Only four years before, he had considered himself a success for being paid £45 a week for his writing. Now his earnings from Swamp Thing alone were equivalent to the average UK salary: DC paid $50 a page, so Moore was earning $1,150 an issue. Due to fluctuating currency rates in 1984, this would convert to anywhere between £810 and £890 a month. Perhaps the most salient exchange rate is that Moore got paid more for his first issue of Swamp Thing than for all the work he had done on Marvelman in the three years to that point.

Moore had come to DC’s attention because of his British work, but his two best-regarded series for 2000AD started after his Swamp Thing debut.

The first was DR & Quinch. The characters had been created by Moore and Alan Davis for a Time Twister that appeared when Moore had been about halfway through writing Skizz (#317, May 1983). That was intended as a one-off, but the reaction to it was so positive that the characters were given their own series, which proved wildly popular when it debuted in January 1984. DR & Quinch was – by Moore’s own admission – a rip-off of OC & Stiggs from National Lampoon. Two teenage delinquents, aliens with a flying hotrod, create havoc wherever they go – whether they’re chasing a girl, being drafted into the army or attempting to make a Hollywood movie. Davis was pleased, saying, ‘I’m very proud and fond of them; they’re easy to draw, they look funny no matter what they are doing, and it was fun to see what they could do and how far I could push them.’

Moore was less keen: ‘DR & Quinch are probably the comic strip that I shall ask to have eradicated and destroyed upon my deathbed. What DR & Quinch are is a continuation of the Great British comic tradition of making heroes out of juvenile delinquents. If you imagine Dennis the Menace with a thermonuclear capacity, you’re probably pretty close to the idea of DR & Quinch. Maybe it’s a sign of the times, I don’t know, but certainly in this country they are probably the most popular creations I’ve come up with.’ He later clarified his position: ‘It makes violence funny, which I don’t think is right. I have to question the point where I’m actually talking about thermonuclear weapons as a source of humour …’ He admitted, however, ‘There were a lot of good things about DR & Quinch. I think Alan Davis and I both put a lot of nice work into it and some of it is amusing. But it has no lasting or redeeming social value as far as I am concerned.’

Moore was a lot happier with another new creation for 2000AD. The Ballad of Halo Jones was a story about an ordinary young woman in a vast science fiction landscape. The artist was Ian Gibson, who had brought his fluid, cartoony style to numerous strips for 2000AD, most notably Judge Dredd and Robo-Hunter. He was keen to work with Moore and was introduced to him by 2000AD editor Steve MacManus at a party. Gibson suggested they could work on a story with a female lead, and they quickly agreed she should be ‘a totally unexceptional character, somebody who could just be the girl next door’, a celebration of the triumphs and tragedies of everyday life. Moore’s preferred technique was to meticulously build up his worlds through little details, and he found a kindred spirit in Gibson, who Moore credits with ‘providing as many of the main concepts and small touches as myself’. It was Gibson who provided the basic idea for the story of Book One: ‘I told Alan that the best way to get to know a place is to go shopping in it. And it seemed like an ideal “girl” story – without being too chauvinist, I hope. I remember saying to Alan “Imagine what it is like if going shopping is like a military expedition, requiring planning ahead of time. If there is a hostage situation in Sainsbury’s and a fire bombing of Tescos etc.” He turned my suggestion into a very fine tale!’

Moore had finally achieved his ambition of creating a running space opera for 2000AD. Now, Halo Jones is regularly cited as a high point of the magazine’s long history. Then, it was a different story. Every week the magazine polled its readers on their favourite strips, and Halo Jones was notably unpopular during its first run (#376–385, July–September 1984). Moore accounted for this as follows:

Naturally, given its nature, the strip wasn’t really for everyone. Some found our decision to dump the reader straight in at the deep end with a totally alien society and let them figure it out for themselves to be merely confusing and irritating. Then, of course, there were those readers who complained that very little happened in the strip. Personally, I think what they actually meant was that very little violence happened in the strip, but it was their 24p a week and they had every right to be bored if they damn well want to be. In short, for numerous reasons, not everybody liked Halo Jones Book One. But we did. And the people at 2000AD did.

Meanwhile, another project that had been among Moore’s earliest writing ambitions was coming off the rails. Warrior #21 (August 1984) saw the last appearance of Marvelman. Artist Alan Davis has offered the most succinct reason why: ‘By the time I had given up on Marvelman it was really a bit of a snake pit of egos.’ Five years later, Moore would pass both the writing duties and his stake in the character on to Neil Gaiman with the words ‘this may well be a poisoned chalice’. Marvelman became the focus of a great deal of ill will, much – but by no means all – of the animosity being between Moore and editor Dez Skinn. As Moore explained: ‘I was not on the best of terms with Dez Skinn by the end of the Warrior experience. I didn’t trust the man, and my opinion – for what that is worth – is that there was knowing deceit involved in the Marvelman decision.’

The dispute over Marvelman would have subsequent implications for Moore’s work for Warrior, Marvel UK and 2000AD. Earlier in his career, he had stopped working for Doctor Who Monthly in solidarity with Steve Moore, and there’s some evidence of friction over editorial changes to work for ANoN and Sounds. The dispute with Skinn, though, was the first of several truly spectacular fallings-out Moore would have with his publishers, disputes which have tended to conform to a pattern.

Moore’s understanding of the dynamic between himself as a writer and his editor/publisher has always been that he (and his artists) should be trusted with total creative freedom and that his publisher’s job is to deal with the commercial side of things: marketing, rights issues, legal matters, merchandising and so on. In 1983, Moore had said: ‘The major benefit of working for Warrior is that we’re all allowed to do more or less what the hell we like. Dez knows we’re all competent professionals and tends to trust in our judgement on aesthetic matters. From the response we’ve had I don’t think we’ve let him down so far. If anything I think Warrior has benefited immensely from the diversity and outlandishness of much of its content. It sets us apart and makes us different. It enables us to make artistic progressions of a sort that the major companies are too nervous to even contemplate.’

Generally speaking, Moore’s editors are initially very impressed by his enthusiasm and the level of thought that has gone into his scripts, and tend to leave him alone. Inevitably, though, at some point, an editor will suggest some change to a script that Moore disagrees with. When asked about Warrior in 1986, Moore told interviewer Neil Gaiman that the promised ‘creative freedom was only gotten after a lot of arguments with the editor’ and Skinn had said, even in happier times, in the pages of Warrior itself: ‘Alan and I have such arguments you wouldn’t believe. He cares about his characters with a passion that’s quite unbelievable. It can make an editor’s life hell! … But the alternative, of not caring, merely hacking the scripts for unknown artists, and never looking at the end product is far more frightening to me.’

There had been a number of specific disputes. In On Writing for Comics, Moore related: ‘I have had at least one editor within the field tell me that there was no point in risking the alienation of even one reader, the solution being to soften the dialogue of the sentence in question until it had no teeth left with which to maul even the most sensitive member of the audience … there is such a thing as being offensively inoffensive.’ The editor in question was Skinn. Comics journalist Pádraig Ó Méalóid asked them both about the incident. Skinn’s side of the story is: ‘For Alan, I think things got tarnished when I suggested we edit out such words as “chocolate” (about [black character] Evelyn Cream), “virgin” (in the context of a twelve-year-old boy) and “period” (about Liz missing hers) – all from the same Marvelman script (#7, I’ve just checked specifics). We’d lost W.H. Smith only a few weeks earlier because somebody’s mum had complained about the “adult nature” of the Zirk strip in #3 … I couldn’t afford a trade backlash against us.’

Moore elaborated on the consequences:

Warrior was aimed at a fairly intelligent readership, we hadn’t had any complaints, and I tended to think that this was a hangover from Dez Skinn’s days at Marvel, and he mentioned lots of things – ‘Why offend even one reader?’ – to which I responded, ‘Because the alternative is to gear your entire product to the most squeamish and prudish member of the audience’. I said that I’m not happy going along with that. Eventually, the argument got down to, well, if I’d just change one of them, and it didn’t matter which one it was. At which point I said, so, basically, they’re all alright to go in, but you want me to change one of them? And Dez Skinn had said, yes, and that it was a matter of him not losing face, at which point I said, no, that’s an even more ridiculous reason … Probably the breaking point came in a meeting in the New Cross offices. We were arguing over some other issue, at which point I had reminded Dez [about this]. At which point he said, ‘That never happened, Alan.’ This was calling me a liar about something we both knew was true in front of, I suppose, Garry Leach and Steve Moore. At this point I was halfway across the office, and Steve Moore and Garry Leach were saying, ‘Leave him, Alan, he’s not worth it,’ and at that point I ceased my work for Warrior.’

Note that the original dispute was over the script for Warrior #7, which would have been a couple of months before its publication in November 1982. Yet Moore’s last Marvelman appeared in #21 (August 1984) and the last V for Vendetta was written for #27 (unpublished at the time, it was scheduled for publication in March 1985), so the fisticuffs took place at least two years after the initial incident. A year after that, Moore would contrast Skinn’s squeamishness over the word ‘period’ with Karen Berger’s willingness to run a Swamp Thing story ‘entirely about menstruation without the slightest qualm’.

The corollary of Moore’s position is that if an editor starts interfering with his storytelling, Moore feels authorised to start finding fault with their business skills. Moore was not the only person disillusioned with the way Warrior was being run by the time it had entered its third year of publication. As was normal, after a peak at launch, sales of the magazine had levelled out and eventually started to drop. The prospect of sharing profits had evaporated, with Warrior racking up losses of around £20,000. When many of the creators started prioritising better-paid work elsewhere, it triggered a vicious circle that cut the frequency of Warrior’s publication to bimonthly, and so halved its already fairly meagre income. Many of the later strips were little better than filler material, with reprints and new strips written by Skinn himself, while he continued to pay flat page rates to all his creators. Alan Davis has indicated that there was frustration among some of the Warrior writers and artists: ‘There was a situation where the most successful strip was carrying the book and the other strips weren’t earning their way … it started to be an issue that various creators thought they deserved more because their work was receiving more attention than other people’s work. And so it just got pretty nasty.’ Davis had his own reason to be upset:

When I was first asked to pencil Marvelman I never regarded myself as Garry’s long-term replacement – I was only asked to pencil two issues for Garry to ink. I believed I was simply doing some donkey work to help Garry make up time on deadlines … When it was finally made clear that Garry was going to quit Marvelman, to work on Warpsmith, I said I would only agree to continue drawing Marvelman if I was given an equal percentage of the trademark and character copyright Dez, Garry and Alan claimed to own. Each gave me a percentage that made me an equal quarter partner. Remember, Warrior was paying £40 per pencilled and inked page as opposed to £80–£95 from Marvel UK or 2000AD, so working for Warrior was a gamble to secure an equitable, or enhanced, payscale through royalties.

The issue of who owns what rights to Marvelman has been highly contentious for a long time. We can say with confidence that at this point Moore and Leach understood that they had equal shares and that either Dez Skinn or Quality Communications also had a share (there are differing accounts of the size of Quality’s share). To recognise his contribution, Davis was cut into the deal, ending up with the same share as Moore and Leach, with Quality Communications also retaining a share.

Moore had clearly lost his enthusiasm for Warrior. He was no longer pitching new series, writing one-off strips or contributing articles. He stuck with V for Vendetta simply because he had always seen that story as being finite, and as it was two-thirds complete, he felt an obligation to his readers and artist David Lloyd to finish. Lloyd in contrast was more than happy to keep working: ‘Other artists had to go off and do other things to make more money. I was very happy to keep doing it because Dez was still paying me money. And I was doing other work … I don’t know if Alan felt as much loyalty to it as I did, though he probably did. He was doing other things, but it was very important to me. That was fantastic, a great character, I had sympathy for the character. Nothing was more important to us … it was ours. And we could do what we liked with it … We could talk about things we couldn’t talk about anywhere else, because we had that control. I’m not saying I’d have kept doing it if I hadn’t been paid … but we would have still done it.’

Nor did Alan Davis have any complaints about Skinn at this point. ‘Various people had warned me off about working with Dez, because he had a bit of a reputation at the time. Again I don’t know how he warranted that because Dez never ever did anything to me.’ Everyone knew that Warrior, never awash with cash, was in trouble, and tensions were clearly fraying. Davis felt ‘there was no heroic melodrama or valiant struggle for creators’ rights, just practical business decisions muddied by ego and legacy building. Dez had invested heavily in Warrior and was struggling to keep it alive.’

The last, great hope for a lifeline was the prospect of Warrior material being licensed to the lucrative American market. Skinn had been actively pursuing this since early 1983, and initially ‘everybody was cool to let me go with my gut instinct, it had got us this far, so it made more sense than a dozen or more writers and artists all pitching individually. Outside of the expense for them to all fly to the States, not many of them were really that used to negotiating US contracts or pitching and bartering!’ At the 1984 San Diego Comic Convention, over the weekend of 28 June to 1 July 1984, he talked to representatives of the ‘Big Two’ US publishers, Marvel and DC, and was invited to pitch to both companies in New York. The flagship strip of Warrior, Marvelman, was in the paradoxical position of being precisely what the American comic publishers were looking for – a critically acclaimed, adult superhero book, by a writer who was a rising star – but which was also unpublishable by either DC or Marvel because its name contained the word ‘marvel’. Skinn says Jim Shooter, editor-in-chief at Marvel, ‘definitely didn’t want Marvelman, for a quite logical reason. Despite the name, which would make it sound like a figurehead for the company, what we were doing with the character didn’t really represent where Marvel overall was heading. Dick [Giordano] laughed at the thought of publishing Marvelman. They’d had a bad enough time with Captain Marvel! Of course this wasn’t much of a surprise. We realised that Marvelman would be a major stumbling block for anybody.’

The obvious solution would be simply to change Marvelman’s name. There were two options. The first was what DC had done with Captain Marvel for many years: comics starring Captain Marvel were named Shazam!, after his magic word. The comic in which Marvelman appeared could simply be named Kimota!, after his magic word. Alternatively the name of the character could change: as Marvelman has an MM insignia on his costume, the name would have to begin with an M (while speech balloons could easily be edited, correcting art would be far more complicated, and trademarks would also be affected).

Moore had in fact jokingly referred to changing the name to ‘Miracleman’ as far back as the original pitch to Warrior. He and Davis had shown (and quickly killed off) Miracleman, a character who looked just like Marvelman, in a Captain Britain episode featuring superheroes from a parallel universe. In early 1984, however, Moore told Comics Interview ‘I’m not prepared to change the name’, and had already told Skinn and Davis the same thing. Skinn was furious: ‘With Marvelman, we’d all poured our souls into making it work. For Garry Leach, Alan Davis and me, this was where we’d get some financial return for our efforts. We really didn’t care what America wanted to call it. So long as they’d print it and pay us that rare beastie in comics called a royalty. But Alan felt it would somehow destroy the property if the name was changed. That he couldn’t continue writing it as anything other than Marvelman. Great, he’d already made it to big payer DC, on Swamp Thing. Everybody else was still waiting for the call and could use the money. I seem to remember it took almost a year to get him to see sense.’

It’s a characteristic aspect of the pattern of his disputes with publishers that once Alan Moore starts losing patience with them, he adopts a point of principle that seems, to the other side, at best eccentric or self-defeating. This principle is usually straightforward and the logic behind it coherent, but it can come out of the blue. While there’s invariably a noble philosophical cause at stake, it is also clearly a tactic which has the effect of forcing the publisher into bending over backwards to keep him happy.

Skinn had many other Warrior properties to offer. Giordano and DC’s publisher Jenette Kahn were keen on Zirk and Pressbutton; across town, Archie Goodwin at Marvel’s ‘adult’ line Epic also reportedly wanted to publish Pressbutton. Skinn, though, had a sticking point of his own: he wanted a publisher to commit to reprinting every strip from Warrior. He envisaged a range of titles, ideally co-branded with Quality Communications, and had prepared dummy issues using photocopies of Warrior pages and reusing painted cover art: ‘I wouldn’t let them cherry-pick! DC loved Zirk and Pressbutton I remember … But we’d had a very democratic way with Warrior, everybody was an equal, so I felt it unfair to dump any strip in favour of getting a deal with some of the others. I was going the movies-on-TV route, where to get Jaws you’d have to agree to take a few of Universal’s other maybe less sellable movies as part of a bundle. We hadn’t known who’d be our Judge Dredd/Tank Girl when we started, but the magazine wouldn’t have worked without everybody pulling together so I certainly wasn’t about to dump anybody now we could see who the front-runners were. Instead, I put the shorter-run strips or the less flavour-of-the-month ones into US anthologies, with titles like Challenger and Weird Heroes. Only Marvelman and Pressbutton had their own titles.’ This was not something either Marvel or DC were interested in. Skinn returned to the UK empty-handed, and began preparing pitches to smaller American publishers.

Marvelman now ground to a halt. Moore told Skinn he would not be writing any more Marvelman scripts for the time being. This was no problem in itself – he had already delivered scripts for several future issues – but now Alan Davis joined in, withholding his artwork because he hadn’t been paid for his last batch. Skinn was prompted to explore at least one other avenue: a young Scottish writer named Grant Morrison had submitted a spec Kid Marvelman script, and Skinn sounded him out about becoming the regular Marvelman writer. Many years later, Morrison would recall:

I didn’t want to do it without Moore’s permission, and I wrote to him and said, ‘They’ve asked me to do this, but obviously I really respect your work, and I wouldn’t want to mess anything up, but I don’t want anyone else to do it, and mess it up.’ And he sent me back this really weird letter, and I remember the opening of it, it said, ‘I don’t want this to sound like the softly hissed tones of a mafia hitman, but back off.’ And the letter was all, but you can’t do this, you know, we’re much more popular than you, and if you do this, your career will be over, and it was really quite threatening …

For Moore, this is a version of events that ‘as far as I know has no bearing upon reality at all’. He remembers Morrison’s script and that ‘Dez had rather sprung it on me out of the blue, and it didn’t fit in with the rather elaborate storyline that I was creating … I can only imagine that Dez Skinn told Grant Morrison what I’d said. As far as I remember, and this would be quite a serious aberration if I’d forgotten something like this, but I am almost 100 per cent certain that I never wrote any kind of letter to Grant Morrison, let alone a threatening one. Of course, if you were able to produce this, I would be willing to think again.’ In a 2001 interview, Skinn implied he had been the one to pass the news to Morrison – ‘Alan’s reply was, “Nobody else writes Marvelman.” And I said to Grant, “I’m sorry, he’s jealously hanging on to this one”’ – but he says now ‘I do remember the situation. I never saw or asked to see the letter Grant got, though … I enthusiastically sent Grant’s wonderful little cameo story up to Alan Moore, ill-aware of his growing possessive paranoia (for want of better terminology). But I quickly became aware of (and surprised by) how jealously he was guarding his position.’

Whatever the rancour in the air, Skinn clearly bore Alan Davis no ill will, assigning him a three-part Pressbutton story. For his part, Davis made it clear he wanted nothing more to do with Marvelman, and returned his stake to Garry Leach.

Alan Moore wasn’t only losing patience with Dez Skinn and Warrior in the summer of 1984, he had also severed ties with Marvel UK. Two reasons were stated: first that the company’s accounts department had become slow to send out cheques; second that his favourite editor, Bernie Jaye, had left the company. He also decided to end DR & Quinch, ‘a Frankenstein monster that got out of hand. I was going to do a one-shot story … It went on beyond the point where I would rather have finished it off.’ The net effect was that he had abruptly stopped working with Alan Davis on all three strips they’d been collaborating on at the start of the year. Their last regular DR & Quinch appeared in #367, in May 1984; their last instalment of Captain Britain appeared in June; their last Marvelman was published in August. For the moment at least, however, they remained friends. Davis continued to draw Captain Britain and DR & Quinch, with Moore’s recommended successor, Jamie Delano, his old pal from the Arts Group days, writing the scripts for both.

While Moore claimed he had left Warrior and Marvel UK on principle, Davis notes that he ‘clearly quit both Captain Britain and Marvelman at virtually the same time but claims external, unconnected reasons for both. Isn’t it simpler to accept that with Swamp Thing and new offers from DC – which were far better paid – the volume of work increased to a point where choices had to be made? I know I, amongst many other creators, was hoping for a call from DC.’ Moore continued to work in British comics – not just on Maxwell the Magic Cat, but for 2000AD and a variety of smaller publications – but whatever was motivating his choices, his American breakthrough had clearly changed things. Barely a year before, he had been happy to let Dez Skinn try pitching to US publishers; now he was in direct contact with senior management at DC. They were keen for him to take on more projects with them, and offered lavish production values and generous deadlines. It wasn’t just the promise of jam tomorrow: DC were publishing Swamp Thing every month without fail. He was now a star name at DC Comics, with Dave Gibbons only half joking when he referred to him as DC’s ‘golden boy’.

Moore’s second project for DC was a short Green Lantern Corps story, drawn by Gibbons (Green Lantern #188, May 1985), but characteristically, he had plenty of plans for the future. He worked with Kevin O’Neill on developing Bizarro World and The Spectre, and at least considered reviving the Demon (who had made a couple of appearances in Swamp Thing). By December 1983, he had pitched a Lois Lane series and expressed interest in the Metal Men. He and Gibbons also talked about revamping science fiction series Tommy Tomorrow, although they seemed motivated solely by their amusement that the lead character wore shorts. Meanwhile Moore wrote one-off strips for Green Lantern, The Omega Men, Green Arrow and Vigilante. And DC signed up Moore and Brian Bolland to produce a Batman/Judge Dredd crossover series: as Bolland explained in October 1984, ‘the whole premise would have been that Judge Dredd is an organ of the law whereas Batman represents justice, and the story revolved around the conflict between these two, and the misunderstandings that would arise from the two completely different ways of looking at how society is run.’ The project fell through, Bolland claimed, when IPC could not be convinced ‘that Batman was a viable character’. By the beginning of 1985, Moore and Bolland had moved on to start work on a story that pitted Batman against the Joker.

Moore’s Swamp Thing editor, Karen Berger, was delighted with his work and encouraged him to take risks, backing him up when he did so. Or, as Moore rather pointedly put it, speaking at a 1985 convention: ‘Karen’s great. She’s really nice … She reads the stories, and she supports us. I think one of the problems we have in Britain is that editors feel they’ve got to edit. It’s like policemen who don’t get promoted until they’ve made a certain number of arrests … They want to deliberately change something just so that they can say, “Yeah, I edited this”.’

While DC were not able to publish Marvelman, they were interested in other stories from Moore that applied real-world logic to superheroes. The DC Universe was a playground full of interesting characters, but permanent change was not possible – a writer couldn’t blow up New York or have a nuclear war, or even age the characters. So Moore began drawing up plans for a superhero story set in its own self-contained world. Originally, he used the Archie Comics superheroes the Mighty Crusaders, but when he was told that DC had bought the characters previously owned by defunct publishers Charlton, he decided they would be ideal for his story, and started referring to it as The Charlton Project. The heyday of the Charlton heroes had been a period in the late sixties when characters like the Peacemaker, the Question and Blue Beetle had appeared in a coordinated line of superhero titles created by writers and artists like Steve Ditko, Jim Aparo, Denny O’Neill and Dick Giordano. Part of the appeal for Moore was precisely that the characters were so generic. He drew up a proposal for a six-part limited series, Who Killed The Peacemaker?, a story in which the Question investigates the murder of one of his colleagues, only to uncover a conspiracy to destroy New York with a faked alien attack.

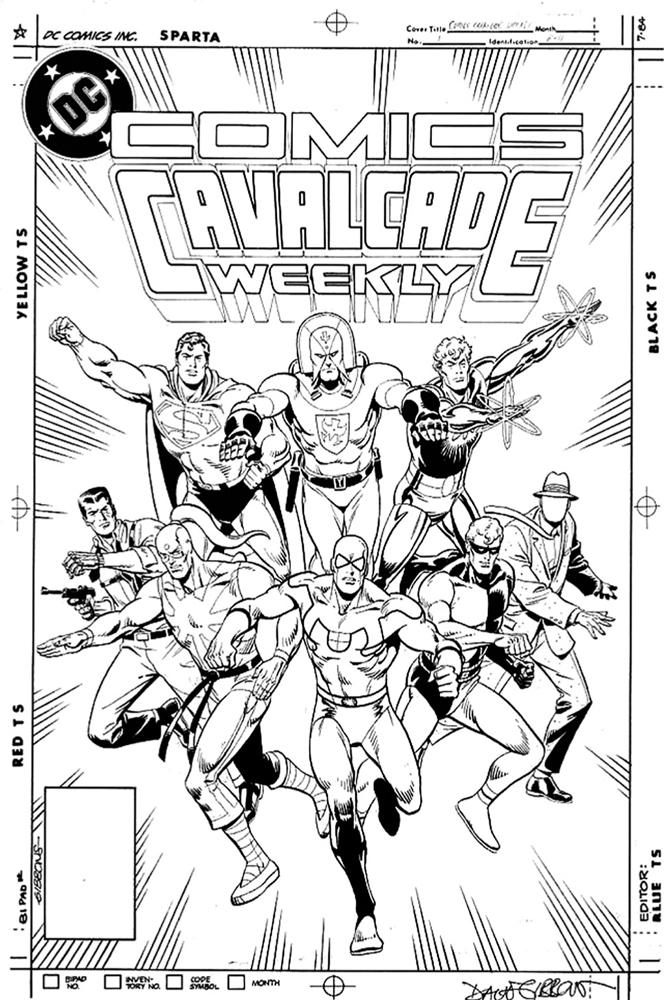

Dick Giordano received the unsolicited proposal in early 1984. His first instinct had been to encourage Moore to take the characters further into ‘adult’ territory, but he balked when he saw just how far Moore wanted to go. Dave Gibbons had successfully lobbied to become the artist on the project at a comics convention in Chicago (and, while there, also persuaded long-time Superman editor Julius Schwartz to commission a Superman Annual from himself and Moore). A few years later, Gibbons produced a mock-up cover of Comics Cavalcade Weekly, featuring the Charlton superheroes as a prototype for a weekly anthology comic:

This had been what DC had in mind for the Charlton characters – an integration into the DC Universe’s superhero community (note the presence of Superman). Giordano telephoned Moore and persuaded him, after some initial reluctance, that he should rework the story with original characters. The Charlton characters were given to other creators, and over the next few years books like Blue Beetle, The Question and Captain Atom showed up. Moore and Gibbons were surprised how much creative freedom using new characters gave them, but the biggest consequence was that they were offered a contract that classified their series as ‘creator-owned’, meaning they would own the rights and would be given a share of the merchandising and other licensing deals. This progressive approach appealed to Moore, as it represented exactly the same ideal that Warrior had aspired to: a free hand for the creators, a savvy business operation getting the finished product out to readers, and everyone sharing the rewards. Moore and Gibbons spent many months discussing the project, writing notes and making sketches. After one Westminster Comic Mart, they finalised the look of their new characters.

Warrior had acted as a talent showcase – as did 2000AD – but American editors proved to be far more interested in the creators than their creations, and could bypass the middleman, getting in touch directly with the writers and artists who interested them. Moore was only the most prominent British comics writer who was now working for American publishers. In the wake of his success, DC in particular would send senior editors to London to headhunt creators. Tellingly, in Warrior #26 Dez Skinn characterised this mass recruitment as an ‘American attack on UK talent’. Just two years after the launch of Warrior, it was Alan Moore, another fan-turned-pro, one who’d barely had a professional credit in mainstream comics when Skinn commissioned him, who was reaping the rewards. Moore’s take on the situation is ‘I think it was that Dez Skinn … wanted to be Stan Lee. He wanted to be the person who got all the credit, whose name was on the whole package – Dez Sez, back in Hulk Weekly – and that’s how he saw himself … I think that the fact that Warrior was mainly attracting attention for the artists and the writers, and specifically for me, that might have been the root of the problem – I’m only guessing.’

Nevertheless, Skinn did find a US publisher interested in republishing the whole Quality Communications range: Pacific Comics. ‘It was the whole lot or nothing,’ he says. ‘I didn’t want any of the gang left out. So Pacific became the only game in town. Obviously until I had a deal in place there was nothing to tell the creators.’ Pacific were a small company, but they published Jack Kirby’s new series Captain Victory and – to great critical acclaim – Dave Stevens’ The Rocketeer, and were known for their high production values and commitment to creators’ rights. Skinn helped prepare mock-ups of issues. Proceeding as though it was a done deal, in the late summer of 1984 Pacific sent an order form to shops advertising eight comics that they planned to release in September. One of these was Challenger:

This was clearly premature. Moore and Lloyd knew Skinn had been negotiating with Pacific, but both were very hazy on the details, and nothing had been signed. Lloyd admits, ‘There was no clear agreement or we’d have run it … It was a very foggy area for me … Dez did all that. He was effectively agenting it.’ It also proved academic – at the end of August 1984, employees at Pacific were told that the company was winding down, and the following month they declared bankruptcy.

Shortly after that, Moore went to the United States for the first time – at DC’s expense – to attend the Creation Convention. A limousine whisked him from JFK airport to DC’s Fifth Avenue offices. He was greeted by Paul Levitz, then the vice-president of the company, with words that confused Moore: ‘“So, Alan Moore. You are my greatest mistake”. Sort of ambiguous to say the least. I just figured it was a kind of neurotic, American business thing that I didn’t quite understand.’ Moore met Karen Berger, John Totleben and Steve Bissette on the first day, and a number of other esteemed comic book creators (including Marv Wolfman, Walt and Louise Simonson – Walt showed Moore his new gadget, a ‘word processor’ – Rick Veitch, Howard Chaykin, Len Wein, Frank Miller and Lynne Varley) over the remainder of his visit. He participated in a Swamp Thing panel at the convention, then met Julius Schwartz, the legendary editor of the Superman books he had loved as a child, now seventy and still very much in charge of the character. Moore ‘knew his name before Elvis Presley’s … being a megalo-star of some stature myself, I obviously feel awed by very few people, and Julius Schwartz happens to be one of them … we hit it off immediately’. They discussed the Superman Annual Moore would be writing, and when Moore flicked through Schwartz’s scrapbook of souvenirs and mementoes he was astonished to catch sight of a letter from H.P. Lovecraft, and to learn that Schwartz had been Lovecraft’s literary agent.

Moore, Bissette and Totleben met Dick Giordano to talk about their plans for further issues of Swamp Thing, and Moore recorded a fairly lengthy video interview DC planned to use to promote the series. He then went to stay with Bissette in Vermont, stopping on the way to meet Gary Groth, publisher of Fantagraphics, and editor of The Comics Journal. After a couple of idyllic days in the tranquillity of Vermont, he returned to New York, where he visited Marvel (‘I don’t seem to have an awful lot to say to Marvel and they don’t seem to have much to say to me’) before returning to Northampton, via Heathrow.

It was around this time that Moore indicated to Dez Skinn that he wanted to take V for Vendetta to DC. Skinn considered what DC were offering ‘a far poorer deal’, but he also had a different objection: ‘I know I was baffled and shocked because it was a sudden move away from our all-for-one/one-for-all approach, but I can’t put a time frame on it. V had definitely been in the dummy US titles which Garry Leach and I had put together so it was a late-on change he suddenly dropped on us … Alan Moore really was starting to be his own worst enemy. Instead of going along with the rest of us and selling a single publishing right on V for Vendetta to Pacific (ultimately Eclipse) he went with a lower page rate and sold the whole caboodle, rights and all, to DC. Outside of them being his new best buddy at the time (Marvel UK, 2000AD and my own little show having served their purpose as his springboard to America) I never could understand what made him do something so insane.’

It would be almost a year before Moore and David Lloyd finalised their V for Vendetta contract with DC. The reasons Moore signed are self-evident: he trusted DC, they would pay him the highest page rates in the industry plus a royalty, they were keenly interested in publishing anything he had to offer and making all the right noises about creators’ rights. In 1984, Moore’s back catalogue divided neatly into four categories: 1) his work for Marvel UK and 2000AD, which he didn’t control the rights to; 2) his work for Sounds, Maxwell the Magic Cat and The Bojeffries Saga, which were all unsuited to the mainstream US market; 3) Marvelman (and the related Warpsmith), which DC couldn’t publish; and … 4) V for Vendetta.

Within a month of Pacific collapsing, Warrior received another blow. On 21 September 1984, Marvel’s lawyers sent Skinn a letter objecting to the use of the name ‘Marvelman’. This had been triggered by Quality republishing a number of old Mick Anglo Marvelman strips in a one-off comic called the Marvelman Special. It was the first time the name had appeared in the title of a magazine, although in his reply, Skinn noted that Marvel UK had known all about Marvelman appearing in Warrior for years and not objected. Four more letters were exchanged, with Marvel seeking a clearer assurance that Marvelman would not reappear. The threat of legal action proved useful to Skinn, as it acted as a smokescreen for the behind-the-scenes problems with the strip. He published the correspondence in Warrior #25 and #26, gaining sympathy from fans.

It also, briefly, saw Moore on the same side as Skinn. Temperamentally distrustful of lawyers, Moore saw the legal action as something akin to an assault on the natural order: ‘Despite the fact that “Marvelman” has been a copyrighted character in England since 1954, it was feared that a certain major American comic company (not DC) might take exception to a comic entitled Marvelman being published upon its own turf. Despite the fact that the company concerned hadn’t adopted their name until the very late sixties, it was decided that corporate clout and legal muscle would be more likely to decide the issue than such comparative trivialities as the concepts of right and wrong.’ In the same issues he published the exchange of letters with Marvel’s lawyers, Skinn was able to trumpet the American reprints of Warrior material, starting with Axel Pressbutton #1 (cover dated November 1984). The small US comics company Eclipse had swiftly bought Pacific’s intellectual property in a bankruptcy sale, and this included the reprint rights to some, but not all, material from Warrior. The deal included Pressbutton, Marvelman and Warpsmith, but – for reasons about which now not even Moore, Lloyd or Skinn are entirely clear – excluded V for Vendetta and The Bojeffries Saga.

It came too late to save Warrior, though. Issue 26 (February 1985) was the last to be published. It saw the first contribution by writer Grant Morrison, an instalment of The Liberators, a new series created by Skinn. Another chapter of that, and of V for Vendetta, were complete but would remain unpublished for some time. That summer, Skinn told Amazing Heroes magazine Warrior would return, but from now on he would insist that he owned any new characters.

Meanwhile, Eclipse Comics pressed on with their plans for Marvelman. Co-founder Cat Yronwode loved the series: ‘It’s a great story. Great art. I thought it was one of the most adult – and I don’t mean pornographic – stories I had seen in comics. I loved where Alan Moore was going with the story from what I’d read in Warrior. And I knew that if he had kept it up, it would be a masterpiece.’ For the time being, though, Moore had little involvement with Eclipse. Even with each American comic reprinting four Marvelman chapters from Warrior, it would be #7 (provisionally scheduled for March 1986, eventually published in April) before any new material would be required from him.

Eclipse had aggressive plans for Marvelman; they made moves to secure the rights to the character, trademarks and the continuation of the story beyond the Warrior material, signing contracts with Quality Communications for Skinn’s company to supply them with completed pages equivalent to twelve issues of both Marvelman and Pressbutton – in both cases, the first six issues would be Warrior reprints, the next six issues all-new material. Most of the comics sold exclusively in comic shops – the ‘direct market’ – were premium products for avid collectors, with a higher cover price than the regular comics sold at news-stands. Eclipse would sell Marvelman only to the direct market, but at the same price point as a news-stand comic, 75¢. It was a conscious attempt to muscle in on DC and Marvel’s territory.

As The Comics Journal reported in February 1985, the name ‘Marvelman’ remained a sticking point whichever side of the Atlantic it appeared, and Eclipse weren’t quite sure how to proceed. Moore therefore wrote to Archie Goodwin, a senior editor at Marvel, issuing an ultimatum. Although he had already vowed not to work for Marvel UK again, he still had some leverage, as Alan Davis explains: ‘At the time Alan Moore and I were producing Marvelman and Captain Britain, UK-originated comics were not being taken seriously. There were no contracts between Marvel UK and its freelancers, and the Warrior contracts only ever covered the broad concepts of the series, not specific pages. Because we were being paid so little by both Marvel UK and Quality/Warrior, we were able to sell our work as “first English language edition only.” That is, we sold the company the right to print the work once. After that, they would have to renegotiate for further publication.’

Moore wrote Marvel a further letter in which he stated that he was denying Marvel – both Marvel UK and the American parent company – the rights to reprint any of his work, and to avoid doubt (not everything he had written had been credited to him in the comics) sent them a list of the work. It would be some months before Alan Davis, whose Captain Britain strips formed the bulk of that list, learned Moore had done this, while industry legend suggests that the result was only uncovered years later when someone was clearing out Jim Shooter’s desk. As Moore recounts: ‘Archie Goodwin had said, “Alan Moore’s not going to be working for Marvel in any way, or letting us reprint Captain Britain unless we ease up on the Marvelman deal,” and he’d said, “I suggest that you go along with him.” But Jim Shooter, who was another one of these comic book industry führers, whose will is not to be meddled with, he’d petulantly screwed this letter from Archie Goodwin up and thrown it in the bottom of a drawer somewhere.’ Moore now allowed Eclipse to rename the character ‘Miracleman’. Eclipse’s statement to The Comics Journal, reported in July 1985, that the name change was ‘suggested by Moore’ gives no hint of his mood when he did so. The first issue of Miracleman sold 100,000 copies, making it easily the best-selling Eclipse comic in the company’s history.

With apparently no behind-the-scenes drama whatsoever, Eclipse continued to publish Steve Moore’s Axel Pressbutton, relaunching the series as Laser Eraser & Pressbutton when they started printing new strips instead of Warrior reprints. As planned, twelve issues (and a 3D Special) were published, from November 1984 to July 1986. Other one-off strips from Quality occasionally appeared as back-up strips in other titles, but there was nothing like the range-within-a-range Skinn had envisioned when he was talking to Pacific.

All the while, Moore continued to keep himself busy. He had scaled back his work in British comics, but had not abandoned it altogether, saying ‘I do still want to be involved in the British comics scene, so I don’t feel like a deserter’. After vowing not to work for Marvel UK, however, and with no interest in continuing DR & Quinch, his only major British work at the time was Halo Jones. The lukewarm reaction to Book One meant there had been no guarantee of a Book Two, but it appeared a few months later (#405–415, February–April 1985). This was in part because 2000AD wanted to keep Moore working for them, and ‘both Ian and I were excited about the strip and, to their credit, the editors of 2000AD know that the best chance of getting first-rate work out of creative people is to give them something they’re excited about.’

Book Two sees Halo away from the hermetic world of the Hoop, working as a hostess on a luxury spaceliner. It has more action, less futuristic slang, Halo shows a lot more skin and the story finds a much larger role for her robot dog, Toby, who’d proved very popular. Moore worried at the time that this had been at the cost of fleshing out the world he and Gibson had created, and said that while he was writing it that it was ‘more of a compromise than I’d have liked … having to make concessions to the younger audience tends to blunt the edge of the strip for me’, but in his Introduction to the first collected edition he admitted that ‘looking over the current volume as one complete work, I think we just about managed to pull it off’. Book Two certainly proved extremely popular, and Moore was careful to lay down in it some hints for Book Three, which 2000AD were keen to run as soon as he had time to write it (it would appear in #451–466, January–April 1986).

His other British work tended to be obscure, and was clearly done because it entailed short pieces for friends or projects that intrigued him. Moore was far more prolific in America. He continued to write Swamp Thing, and June 1985 saw the publication of his longest single work to that point, the story For the Man Who Has Everything in Superman Annual #11. He also did a variety of one-off pieces for other companies – including his only work for Marvel US: three pages as part of the famine relief comic Heroes for Hope and a strip for glossy Epic Illustrated.

In the summer of 1985, Moore was approached by Malcolm McLaren, former manager of the Sex Pistols and now working for CBS Theatrical Productions, the feature film arm of the TV network. McLaren had recently discovered Moore’s work (naming a 1985 album Swamp Thing). They spent an afternoon together, and were joined by McLaren’s girlfriend, the model Lauren Hutton. When the impresario told Moore he had ideas for a number of movies and needed a writer, the concept that caught Moore’s eye was Fashion Beast, a retelling of the Beauty and the Beast myth channelled through a fictionalised version of the life of Christian Dior. The idea’s originator had been the writer Johnny Gems (who would go on to work with Tim Burton, notably on Mars Attacks!), while Kit Carson, screenwriter of the 1983 remake of Breathless and of Paris, Texas, had written a treatment the previous Christmas. Memno Meyjes, who’d adapted The Color Purple, had also developed a treatment. Moore completed a draft of the screenplay and was paid £30,000 for it, but CBS Theatrical Productions was closed in late November 1985, and Fashion Beast went into ‘turnaround’ – essentially it was shelved. Moore, however, clearly considered Fashion Beast to be an ongoing project for some time after this – he mentioned the movie in a March 1986 interview with the NME and it was listed as one of his forthcoming works in the collected edition of Halo Jones, published in July of the same year, while McLaren continued to shop it around, with Moore’s script attached. (Although never filmed, it was adapted for comics by Avatar in 2012–13.)

Moore made his second trip to America a year after his first, this time taking Phyllis. In early August 1985 he was a guest at San Diego Comic-Con, which was attended by about 6,000 fans. Here he met Cat Yronwode, his Miracleman editor, in person for the only time. He, Bissette and Totleben and Swamp Thing were showered with Kirby Awards, the American industry’s top accolade: Best Single Issue (Annual #2), Best Continuing Series, Best Writer, Best Art Team and Best Cover (#34). While Moore basked in such accolades, he was far more impressed that he was able to meet the man the awards were named after: Jack Kirby, artist of the issue of Fantastic Four (and so many other comics besides) that had changed Moore’s life. Moore shared a panel with Kirby and Frank Miller – he was embarrassed to hear Kirby praising him and Miller for what they had done for comics – but did not get much time with his idol, saying, ‘all I remember was that aura he had around him. This sort of walnut coloured little guy.’

Moore also held court in a solo panel; a transcript that appeared in The Comics Journal #106 was accompanied by the assertion that based on sales ‘Alan Moore may not be the most “popular” writer in comics right now, but he certainly is the most respected’. It was the first time the American convention scene had been treated to what had become a regular occurrence in Britain – a wild, bearded, surprisingly jovial figure getting an audience to eat out of his hand. Moore threw questions open to the audience and was able to talk about a huge slate of work. He had just finished Batman Annual #11 and his last DR & Quinch story, and was continuing to work on Swamp Thing and Halo Jones (which he was planning to write many more books of). He would like to do a Congo Bill story ‘because he’s a really stupid character’. He was due to start on ‘the graphic novel’ (he used the term) The Killing Joke. He was just about to sign contracts on the DC version of V for Vendetta, and had written the first chapters of Book III. ‘I’m going to be doing a Superman graphic novel, and Julie [Schwartz] wants me to do some occasional stories during his tenure on the book.’ He had also resurrected the title of his unpublished seventies fanzine, Dodgem Logic, as the title of an anthology comic for Fantagraphics, a black-and-white magazine that would feature one 48-page story per issue, drawn by a different artist. (Moore had said elsewhere of the project, ‘If I do this right I hope I’ll be able to bridge a little of the gap between what can be achieved with comics and what can be achieved with serious literature.’) He would never again work for Marvel (following their legal action against the name Marvelman). And he also took the opportunity to announce ‘I’ve ceased all contact with Dez Skinn.’

Around this time, Alan Davis was talking to Jamie Delano, now the writer of their Captain Britain series: ‘He told me about Alan being snubbed by Jim Shooter and, in retaliation, denying Marvel permission to reprint Captain Britain – nothing to do with the Marvelman name. I confronted Alan, told him to withdraw his objection to the Captain Britain reprints or I would deny Eclipse my Marvelman rights. Which I eventually did! Eclipse, Dez and Alan all ignored my protests/refusals.’

To add insult to injury, Captain Britain was an ongoing series – Moore’s writing stint fell between runs by Dave Thorpe and Delano. By blocking the reprints of the middle of the story, Moore hurt the chances of any of Davis’ Captain Britain run being collected. Davis was annoyed that Moore had taken this course of action in, as he put it, a ‘fit of anger’, but the real issue was that ‘Alan hadn’t bothered telling me … I found out, sort of like, five months after he had actually said that and just because someone assumed I already knew’. Reacting to Marvel’s intransigence over the use of the Marvelman name and the departure of Bernie Jay, Moore says: ‘I just thought that me and Alan Davis were pretty much on the same page with everything, although that may have been a misunderstanding upon my part and I perhaps didn’t do enough to make sure that was the case.’ But the relationship between the two men became strained – Moore believes Davis purposefully avoided him at a convention they attended around the time.

Davis had just had his break in the US industry. He became the artist on Batman and the Outsiders from #22 (June 1985; it sold about 140,000 copies a month compared with Swamp Thing’s 95,000), and would be promoted to the main Batman title, Detective Comics, the following year. Moore was able to block reprints of Captain Britain because he had only granted first English language edition rights, and, despite the artist having returned his stake in the character, the same applied to Davis’ artwork on Marvelman: Davis could make a very simple tit-for-tat response. On 16 July 1985, Dez Skinn wrote to Moore to inform him that Davis was refusing permission to reprint Marvelman Book Two, or to let Eclipse use his designs for characters like Evelyn Cream, Sir Dennis Archer and Marveldog. He also informed Moore that Garry Leach was happy for his work to be reprinted, but had not agreed to his designs being used in any new material (Leach’s designs, critically, included the series logos, the Marvelman insignia, Marvelman’s costume, and the main characters Mike Moran, Liz Moran and Johnny Bates). Skinn told Moore he ‘would appreciate being informed of your intentions’.

What happened next is hotly contested, and ended Moore and Davis’ friendship. Davis later said, with some regret, ‘Alan and I had a great working partnership and what I thought was a solid friendship for more than three years. We were both there at the end. We both know the truth. If his version differs from mine it becomes a matter of who you choose to believe.’

Moore does not seem to have addressed the Captain Britain issue, and did not contact Davis. Instead he concentrated on resolving the issue of Davis withdrawing his consent to use the Marvelman material. Cat Yronwode asserts that Davis ‘sold … his one-third share of Miracleman, to Eclipse’, and Moore says he ‘was told that Alan Davis had sold out his rights’. Davis’ position is a flat denial: ‘I did not give or sell anything to Eclipse. I have only ever sold a single right, to one English language publication, of any of the Marvelman pages I drew, for their first appearance in Warrior.’ Moore told Yronwode he would not contribute any new Miracleman material until he had written proof that Davis had given permission. Rumours about the dispute were inevitably to end up in the comics press: Cat Yronwode took a hard line with Davis, telling Speakeasy magazine in late 1985, ‘Dez Skinn signed a contract with Eclipse allowing us to reprint material from Warrior, and we intend to reprint that material. If Alan Davis granted Dez Skinn the power to make that contract, and has since changed his mind, that is unfortunate for Alan but he is legally bound to that contract. If Dez Skinn represented himself to Eclipse as having the power to represent Alan Davis when in fact he did not, that is a matter for Alan Davis to settle with Dez Skinn. In any event Eclipse will be reprinting the material.’

Of course, Moore was now far from happy about the idea of working with Skinn, and took active steps to ensure he would not have to. In October 1985, Skinn was in America. There mainly to liaise with Eclipse about Miracleman, he had met with DC and understood he had been offered an editorial job there. An article on Skinn’s blog explains: