‘At his fortieth birthday party, he declared himself a magician. He wasn’t of course. He couldn’t even do balloon animals. Not long after that, he started worshipping a snake. You can see how we might have worried about him.’

Leah Moore, Introduction to The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore

On 18 November 1993, Alan Moore announced to his friends and family that he would be devoting his time to the study and practice of magic – and early the following year, he declared that he had become a devotee of the snake god Glycon. Since then, much of his work has been inspired by his exploration of magic, even ‘subsumed within magic’, while the art itself represents ‘communiques from along the trail’ of his progress.

Most interviews with Moore and articles about him have made a point of touching on the subject of his belief system. His pronouncements contain clear elements of showmanship and bullshitting – he once told the NME ‘I am a wizard and I know the future’, and fobbed off another interviewer with the reply ‘since the Radiant Powers of the Abyss have personally instructed me to prepare for Armageddon within the next twenty years, this is all pretty academic. Next question’ – but this theatricality is entirely consistent with his brand of magic, indeed is a vital part of the process.

Moore is a magician who is more than happy to explain what he is doing and what he hopes to achieve: ‘I’m prepared to lay it on the line: if I do something … I’m quite prepared for people to say “Well, that isn’t magic”. Or, “That isn’t any good”,’ he says with a chuckle. ‘I’m prepared to do it in the open, on a stage, in front of hundreds of strangers and they can decide whether it’s magic or not. That seems to me to be the fairest way. Not to put yourself above criticism by only performing in darkened rooms with a couple of initiated magical pals. Do it in the open, where people can see what you have up your sleeve. Where they can see the smoke and the mirrors. And where they can see the stuff that appears authentic.’ Regular revelations in interviews and essays along the lines that he had advanced so far as to be exploring the sixth of ten Sephira of the Tree of Life, or that he had on 11 April 2002 ‘acceded to the grade of Magus, the second highest level of magical consciousness’ have led numerous critics, readers and colleagues (although, tellingly, few friends or family) to wonder if Alan Moore has gone at least a bit mad.

Since walking away from DC, Moore had worked on Big Numbers, From Hell and Lost Girls, all projects defined both by great artistic ambition and a vicious circle of massive delays and funding issues. He had been writing his prose novel, Voice of the Fire, but this was also proving to be slow going. Nothing came of his plan to illustrate Steve Moore’s Victorian-set graphic novel Endymion. And though a book recommended to him by Neil Gaiman – Richard Trench and Ellis Hillman’s London Under London – inspired plans for Underland, a graphic novel for older children set in a magical subterranean kingdom beneath London populated by weird fantasy characters, this was scuppered when Moore learned Gaiman himself had a very similar project underway, which became the prose novel and TV series Neverwhere.

As the publisher of Big Numbers, Moore had sunk his own money into the series, including $20,000 to the artist Bill Sienkiewicz, but its publication had ground to a halt after two issues. In an interview published in November 1993, Moore described it as ‘a catalogue of misfortune from start to finish. I have written about 200 pages of it. Five episodes. Bill Sienkiewicz, after completing three episodes, felt defeated and was unable to continue it … Al Columbia stepped up. I believe Al completed one issue, but I’m not sure what happened to that … I seem to be leaving these artists as smouldering wrecks by the fire.’ With nothing to sell, Mad Love could generate no money. This frustrated Moore: ‘We were selling tons! For a black-and-white book that isn’t about superheroes, the first issue sold 65,000 copies, which is better than most DC titles, I believe. There was a potential there for establishing alternative comic publishers as a real force … but unfortunately the perception will be that Big Numbers isn’t out anymore so it must have been a commercial failure. It was by no means a commercial failure. It was a massive success that earned me more money than any other comic I’ve ever done.’

From Hell and Lost Girls both featured in the horror anthology Taboo, published in America by Moore’s friend and Swamp Thing artist Stephen Bissette. Taboo had begun publication in 1988, and attracted top talent from the worlds of both comics and horror like Ramsey Campbell, Moebius, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Charles Burns, Dave Sim, Clive Barker and Neil Gaiman. Yet it was soon mired in similar problems to Big Numbers, and only seven issues were published in five years. Moore had agreed to split a fee of $100 per page with his artists for his work on the anthology, but to pay even that Bissette and his family were forced to exist on a diet of macaroni and cheese.

To add insult to injury, the mainstream comics industry had boomed, and a lot of freelancers who had stuck to writing superheroes were making unprecedented amounts of money: there were rumours that X-Men writer Chris Claremont had bought his mother a private jet. The artist on that series, John Byrne, would later testify in court that Marvel had paid him around $5 million in the eighties, that he had made ‘a couple million dollars doing Superman’ and ‘four or five million doing the Next Men’ (a creator-owned series published through Dark Horse starting in 1991). Grant Morrison was another to benefit: he wrote Arkham Asylum, DC’s first original hardback graphic novel, a Batman story with fully painted art by Dave McKean which came out in time for Christmas 1989, the year Tim Burton’s Batman movie was the biggest summer blockbuster and then the best-selling videocassette. On the basis of pre-orders alone, DC were able to cut Morrison a cheque for $150,000, and royalty payments quickly bumped that up to half a million. It remains the best-selling original graphic novel of all time.

If not so awash with cash, the British comics scene was equally fevered. When Alan Grant, John Wagner and Simon Bisley signed copies of a Judge Dredd/Batman comic at the Virgin Megastore in Oxford Circus, they proved to be the store’s biggest ever attraction, beating the record set by David Bowie. Extra police had to be drafted in to manage the crowd. The big success story, though, was Viz. A scatological parody of kids’ comics like the Beano and Dandy, Viz had started life as a photocopied fanzine sold in Newcastle pubs and record shops. By 1985, 4,000 copies of each issue were sold and it came to the attention of Virgin Books, who began distributing the magazine in Virgin stores nationwide. Three years later it was selling half a million copies a month; by 1990 sales had doubled again and it was the fourth best-selling magazine in the country. It spawned many short-lived imitators like Poot, Smut and Zit, as well as Brain Damage, which used veteran underground comix creators like Hunt Emerson and Melinda Gebbie, and Oink!, a deceptively smart, rude children’s comic. Viz was a true phenomenon, in the way Mad magazine had been in America in the fifties.

Watchmen acted as the spearhead that encouraged every bookshop to dedicate a shelf or two to comics, but Moore had failed in his attempt to define the ‘graphic novel’ in terms of technically complex, personal work like Big Numbers and A Small Killing. Instead, it came to refer to paperback albums collecting around half a dozen comic books, and comics companies adjusted their business plans – although not always their contracts – to factor in such reprints.

Thanks to deals that gave him royalty payments for Watchmen, V for Vendetta and The Killing Joke, all of which remained bestsellers, Moore did not suffer the fate of the comics creators of previous generations. He also benefited from the many comics shops which had opened, establishing a vast number of outlets for Big Numbers and Taboo, with almost every customer aware of Moore’s name. And although he had sworn off appearing at comics conventions, Moore continued to be interviewed by both the booming comics press and the mainstream media. As one might, he grew increasingly resentful of other people’s material success, especially as much of it was achieved by copying his methods (even John Byrne’s Next Men had followed the lead of V for Vendetta and Watchmen in abandoning thought balloons and sound effects), but his main frustrations seemed to be artistic rather than financial: ‘I could see stylistic elements that had been taken from my own work, and used mainly as an excuse for more prurient sex and more graphic violence … I felt a bit depressed in that it seemed I had unknowingly ushered in a new dark age of comic books. There was none of the delight, freshness and charm that I remembered of the comics from my own youth.’

Despite the money pouring into the industry from graphic novels, many creators working for the big comics companies continued to conclude that the terms on offer did not give them a fair slice of the pie or enough creative freedom especially in Britain. By failing to offer high page rates or royalties, 2000AD had suffered a huge talent drain; as the eighties drew to a close, they were simply unable to retain even the services of new writers and artists unless they had a sentimental attachment to the magazine. Warren Ellis, for example, wrote one Judge Dredd story before beginning a lucrative career in US comics. Conversely, in America, some creators were able to thrive within the existing corporate structure. When his Sandman series proved to be a mainstream hit, writer Neil Gaiman managed to convince DC to extensively renegotiate his contract, retroactively granting him co-ownership of the characters and licensing rights, as well as improved royalty rates on the graphic novel collections of the series.

It wasn’t lost on some commentators that this was exactly what Alan Moore had asked for and not received with Watchmen. Stephen Bissette drew a direct connection:

Neil takes good care of himself. He’s very pragmatic in his company dealings. Believe me, there were plenty of times in the past when DC crossed the line with Neil. He was always diplomatic; he did not give ground, but he would allow them room to ‘save face’, as he put it. Things went better for Neil and Dave McKean and Grant Morrison and Michael Zulli, who is now doing a lot of work with Vertigo. I think DC learned an important lesson with Alan. When Alan walked, they couldn’t quite believe it. I think pressure came down from Warner on some level. This is all supposition on my part, but there had to be a point at one of those board meetings where somebody upstairs said ‘When’s the next Watchmen coming out?’ and they had to admit that they had lost Alan.

Bissette would later quote Gaiman as saying: ‘I saw an interview with Ice-T … and he pretty much summed it up by saying something like “If a creative person is a whore, then the corporation is the pimp and never think your pimp loves you. That’s when a whore gets hurt. So just get out there and wiggle your little bottom” … I’m a whore and a very good one at that. I make my living selling myself … DC doesn’t love me and I don’t love them. So we work together just fine.’

The contrast with Moore’s attitude could hardly be starker. With a career that has neatly segued into novels, movie scripts and television, Gaiman has stated that he learned the art of writing comics from Alan Moore, but it seems just as fair to say that when it comes to the business side, he’s thrived by doing the exact opposite. Or, as Gaiman put it, talking about his dealings with the movie industry, ‘You can learn from your experience, but you can also learn from your friends’ experience, because your friends are walking through the minefield ahead of you and you go, “Ah-ha, don’t tread on that”.’

When the revolution came, though, it was not fomented by British writers with literary ambitions. It didn’t lead to the dismantling of the corporations in favour of small press, black-and-white anthologies and creators keen to eschew musclebound spandex-clad clichés for more personal, difficult work. Instead, a group of ‘hot artists’ who’d been working for Marvel left to create their own superheroes.

While DC were winning awards and encouraging readers to send in their poetry, Marvel were selling a lot of monthly comics in which superheroes beat up bad guys and lived sprawling science fiction soap opera lives. A new generation of artists was now drawing some of Marvel’s most successful books, including Spider-Man (Todd McFarlane), The Amazing Spider-Man (Erik Larsen), X-Men (Jim Lee), X-Force (Rob Liefeld), Wolverine (Marc Silvestri) and Guardians of the Galaxy (Jim Valentino). They shared a broadly similar style, derided by older fans for its single-panel pages, contorted anatomy, speed lines and snarling faces, but it was dynamic and distinctive and by 1991, such comics were selling in vast quantities. The artists were young – only Valentino was over thirty and Liefeld was twenty-four; Lee was drawing X-Men comics while still at medical school – and barely had a professional credit between them five years before. Yet the first issue of a new Spider-Man series, written and drawn by McFarlane, sold 2.5 million copies in 1991, and a few months later, Lee was co-writer and artist on X-Men #1, which became the best-selling comic of all time with over 8.1 million copies sold. Even without these crazy numbers, regular monthly sales of the top books were in the high hundreds of thousands.

So the artists came to a familiar conclusion: although Marvel paid better page rates than DC, the company wasn’t giving the creators enough credit for their contributions, or a fair share of revenue for merchandise like posters. It was clear that in the nineties superheroes would become multimedia properties, the subjects of movies, television series and cartoons. Superheroes were a natural fit for videogames, in particular. Marvel were not only slow and poorly positioned to exploit this, the existing contracts would not reward the artists when they got round to it.

An unintended consequence of assigning books featuring D-list superheroes to the young British writers had been that when those books did well, DC couldn’t argue that it was just because people wanted to read about the character. Sandman’s success was inarguably down to Neil Gaiman, people bought Doom Patrol because Grant Morrison was writing it. Even though just as many people – more – were buying Spider-Man because Todd McFarlane was drawing it, Spider-Man was a perennially popular character, and both Marvel and McFarlane knew that however ‘hot’ an artist was, he was replaceable. This limited the artists’ bargaining power. The solution was a radical one: the six left Marvel to set up Image Comics, an umbrella organisation within which each of them ran their own company, or ‘studio’, sharing marketing, printing and other costs. The creators would retain all the rights to their characters and would aggressively seek to license their intellectual property. There was a certain inbuilt rivalry between the creators, but also a huge amount of creative energy. Liefeld’s Youngblood, Lee’s WildC.A.T.S., McFarlane’s Spawn and Larsen’s The Savage Dragon debuted in the first half of 1992, and sold in huge numbers. The canniness of the operation can be extrapolated from those titles – racked alphabetically, McFarlane’s and Larsen’s comics sat just before Spider-Man, the Marvel character they had been most associated with. Meanwhile, WildC.A.T.S. and Youngblood bookended the best-selling X-Men comics.

Very soon, however, a critical consensus emerged that the Image books tended to have striking art but terrible stories, thin characters and poor dialogue. Spawn had been an instant hit – the first issue had sold 1.7 million copies – but the book’s creator Todd McFarlane hoped he’d created a superhero who would endure as long as Superman or Batman. He understood he would need to find ways to sustain interest in the character. The solution was simple enough for a company awash with money: in the summer of 1992, McFarlane phoned up the top comics writers and made them offers they couldn’t refuse. He signed deals to write a single issue of Spawn with Neil Gaiman, Frank Miller, Dave Sim … and Alan Moore. The issues appeared between February and June 1993, and the writers were paid staggering sums for writing a single comic book: $100,000 up front, plus royalties.

Signing Moore to Image was a significant coup, but McFarlane had not been the only partner to approach him. The first had been Jim Valentino, who’d promised him a miniseries, with only one proviso: it had to be about superheroes. Moore had begun planning out a storyline encompassing superheroes (a Captain Marvel archetype called Thunderman) and horror (Golem, an ‘urban Swamp Thing’), as well as a ‘Lynch meets Leone’ western with a cast of characters all implicated in a murder. Moore had always liked David Lynch’s movies, but was particularly enamoured of the television series Twin Peaks (1990–2). His proposed series included the character Major Arcana, a mystic serving in the US military like Twin Peaks’ Major Briggs. Collaborating with his Swamp Thing artists Rick Veitch and Stephen Bissette, he whittled these ideas down until he had 1963, an arch parody of the Marvel comics from the sixties he had loved so much as a boy, with characters like Mystery Incorporated and Horus standing in for the Fantastic Four and Thor. The pastiche was so complete it saw Moore adopting an ‘Affable Al’ persona in captions, editorials and interviews akin to that of ‘Smiling Stan Lee’ back in the day. Recruiting Moore was a triumph on Valentino’s part, says Bissette:

the other Image partners wanted a piece of that action, which would also trump Jim Valentino’s initial coup. There was apparently more than just a healthy collegiate rivalry involved. Some of it seemed pretty cutthroat from where we sat … Todd McFarlane trumped everyone by inviting Alan to write for Spawn, which led to the whole four-issue Moore/Gaiman/Sim/Miller arc on Spawn. His first issue and miniseries with Alan was already coming out before 1963 #1 hit the stands in April 1993, making it appear Todd had landed Alan.

According to Bissette, ‘Rick Veitch and I found ourselves caught in the crossfire between the Image partners’ pissing contests. We didn’t grasp what was going on at the time – we thought everyone was eager to work together, we didn’t realise the Image partners were in competition with one another …’

In the event, 1963 was not what the audience were expecting from an Image comic – or for that matter from an Alan Moore comic – and reviews were decidedly mixed. In post-Watchmen, post-Dark Knight comics, superheroes were troubled figures who enforced justice by throwing rusty hooks into the bad guys. Moore’s appeal to a more innocent, colourful era was either poorly framed or poorly timed – the problem may simply have been that the new audience Image was carving out just wasn’t au fait with the old Marvel comics, and so was ill-equipped to get the jokes. Moore was building up to a finale in the 1963 Annual which would have pitted the 1963 characters against the ‘grim and gritty’ stars of the Image range, like Spawn and Youngblood, but in the event, disputes and delays between the Image partners meant the Annual was never published – leaving the series as a set-up without its punchline.

The first issue of 1963 sold around 660,000 copies, more than six times the sales of Watchmen, and represented the biggest payday of artist Stephen Bissette’s career. Despite that, it was seen as something of a flop at Image, a company used to million-sellers. Frustrations over the Annual led to considerable rancour between the creators, and as a result 1963 is one of very few Alan Moore projects that has never been collected as a graphic novel.

Moore stuck around though. Over the next couple of years, he went on to write more Spawn spin-offs, as well as one-offs for two other Image books, Shadowhawk and The Maxx. Spawn had enough momentum now that McFarlane could license a movie, an animated series and computer games. In 1994, he founded Todd McFarlane Toys, a company that launched with a line of Spawn action figures but which soon exploded into an operation that brought out wave after wave of toys based on horror movie icons, basketball and baseball players.

Moore was, by any reckoning, a terrible fit for the crassly commercial, art and merchandising-led Image books. For three or four years he had been loudly declaring that he was done with superheroes and, now comics had a vast new audience of adult readers, he was primarily interested in exploring the outer limits of the medium’s potential in ‘serious’ work like Big Numbers:

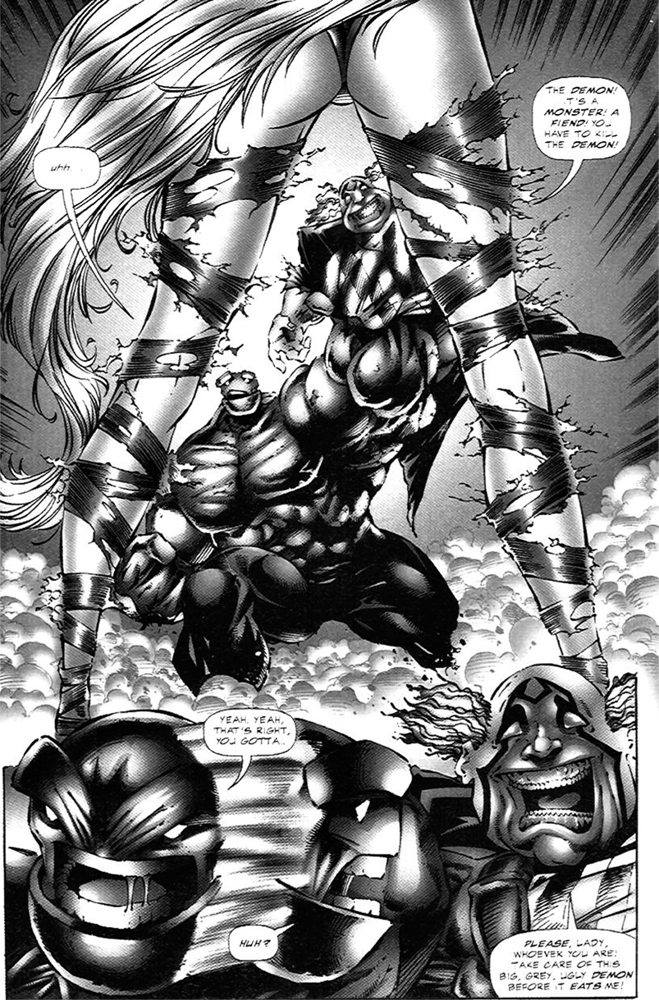

Yet, here, he was writing comics like Violator v Badrock:

One reason – obvious to everyone at the time – that Moore had chosen to work for Image was financial. An interview in comics news magazine Overstreet’s Fan framed it perhaps over-bluntly, and Moore responded in kind: ‘Contrary to what some may believe, Alan’s continuing work with Image is not just for the money … “the money that comes from WildC.A.T.S. or Supreme, that’s very handy. It’s useful to have a source of income that enables me to carry on doing the projects that are dearest to my heart like From Hell, Lost Girls, the CDs that I’m doing; the more obscure and marginal projects, which is where my real interests lie.”’

Nonetheless, he would often find himself batting away the allegation that he had become a pen for hire: ‘I have never done anything purely for the money. If I couldn’t find a way to enjoy the project, then I wouldn’t do it.’ In some of his justifications he sounded uncharacteristically as if he was wriggling to find a loophole in his previous statements: ‘The biggest element for me was the world of imagination that comics opened up! … It was the wonderful concepts, not the superhero’s muscles, which gave me the biggest charge’; ‘I have no desire to be hip in comics. I have no desire to really be part of the comics industry. I have a great interest in the medium … I’m trying to create an interesting realm of the imagination for teenage, adolescent, or even younger boys. And that seems valid.’ But there were other reasons, perfectly consistent with the various stances he had taken: ‘all of a sudden it seemed the bulk of the audience really wanted things that had almost no story, just lots of big, full-page pin-up sort of pieces of artwork. And I was genuinely interested to see if I could write a decent story for that market that kind of followed those general directives’; ‘Although my aesthetics are different from theirs, I admire what the people at Image are doing. They’ve shaken up the industry in a very brutal way and probably shaken it up for the better’; ‘All I really knew about Image was that they’re the opposite of DC and Marvel and that sounded pretty good to me, you know?’

The problem Moore faced was that the Image work was his only new material to see the light of day in this period. He would state in interviews, ‘I’ve nearly finished A Small Killing, after that the next book I finish in about a year’s time will be either From Hell or Lost Girls, and then I will finish Big Numbers’, but only a trickle of this work actually appeared. In 1992, Comic Collector not only called an interview with Moore ‘Out of the Wilderness’, it began: ‘Five years ago, Alan Moore was the most lauded and feted star in the comics firmament. Times change and times move on apace and in 1992 newer advocates to the comics’ cause might be forgiven for asking “Alan who?”’ The dream of a world of sophisticated graphic novels for adults was over, leaving work like Big Numbers that was meant to be the vanguard of the revolution high and dry. As Grant Morrison (who’d ‘managed to write three issues of Spawn in 1993 as the result of a misunderstanding’) later put it, ‘when [Moore] returned to the superheroes he’d made such a show of leaving behind it was clear that he needed money … it was easy to tell that he’d rather be somewhere else, stretching his wings, but even the stentorian Moore had capitulated to the Image juggernaut.’

No one blinks when a successful actor chooses to balance prestigious work for the theatre or in arthouse films with a lucrative appearance as the villain or mentor in a summer blockbuster. While there were undoubtedly people who smirked at Moore for ‘lowering himself’ to work for Image, he was receiving a large amount of money and a high profile for relatively little work, and had struck a deal that granted him far more rights than working for Marvel or DC ever had. If Moore had surrendered, he’d done so on remarkably good terms.

Moore’s bank balance received another significant boost when, in 1994, he sold the movie rights to From Hell. He remained a proud Northampton resident, but around this time he and Melinda Gebbie bought at auction a three-acre farm in Wales, and began the long process of renovating the ruined farmhouse. But Moore hadn’t abandoned his principles to make a buck. In 1996, even Marvel found Image an irresistible force, subcontracting some of their biggest titles – Fantastic Four, Thor, Iron Man, Captain America and The Avengers – to Image’s Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld and relaunching the titles under the banner ‘Heroes Reborn’. Lee offered Moore the chance to write Fantastic Four, but Moore turned down what would have been another huge payday, still unwilling to work (even indirectly) for Marvel. Indeed, despite Morrison’s assertion, the problem might actually have been that Moore was enjoying himself a little too much at Image: ‘1963 has been a great deal of fun. It’s given me a great burst of energy that has been very refreshing in the midst of more demanding projects. It’s a bit like customarily working in a symphony orchestra, but playing in a bubblegum band on weekends.’ Moore’s work for Image certainly represented his most blatant attempt to write ‘something commercial’ and ‘fit in’ since his very earliest days as a freelance comics writer. His private life was about to become far less conventional.

Alan Moore’s personal situation had changed beyond recognition. He had become famous enough to be a ‘cultural icon’. After years when Mad Love – and presumably the breakdown of his marriage – had absorbed much of his DC income, Image had stabilised his finances. His daughters had moved to Liverpool with his exes Phyllis and Debbie, but they remained on good terms. Moore had also moved, albeit to another house in Northampton, with Melinda Gebbie living nearby and had delighted his parents by buying them a large greenhouse with some of his Watchmen money. (The Chinese whispers of comics fandom transformed this into a ‘large, green house’, evidence of Moore’s fabulous wealth.)

Ironically, Moore was also literally playing – or at least singing – in a bubblegum band at the weekends. He had met guitarist Curtis E. Johnson, who set Moore’s lyric ‘Fires I Wish I’d Seen’ to music, and they recruited Chris Barber of Bauhaus (bass) to record it at the Lodge studios in Northampton under the name the Satanic Nurses. The three were then joined by Peter Brownjohn (drums) and Tim Perkins (viola) as The Emperors of Ice Cream, the name Moore had wanted to call his band in the mid-seventies. Moore wrote over a dozen more songs for the group. As Johnson remembers:

We did about three gigs with that line-up and at each gig our girlfriends were all sitting at a table near the stage, I thought they should have as much fun as we are having and so the ‘Lyons Maids’ were born, comprising Ros Hill – who accompanied ‘Murders on the Rue Morgue’ with some wonderful contemporary dance – Sarah Parker and Melinda Gebbie. It was very visual, the entire backcloth was white nylon and various early cartoons were projected onto it – Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend, Little Nemo, Gertie the Dinosaur. During the song ‘London’, huge ultraviolet lights flooded the stage and the ultra-white suit Alan was wearing [handmade by Hill and Gebbie] and the backdrop lit up in ultraviolet whilst the Lyons Maids threw ultraviolet gris-gris in the air.

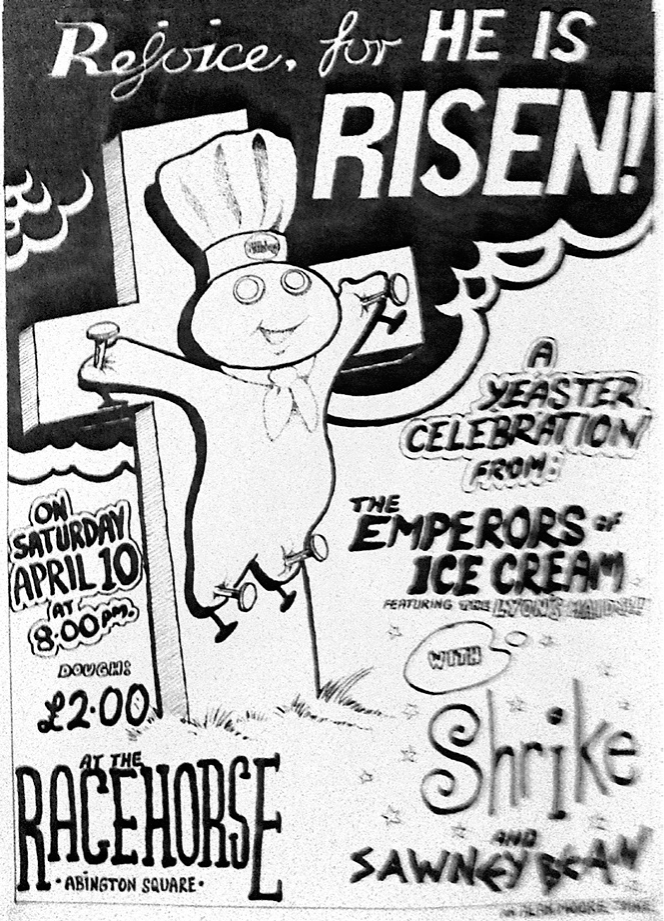

We did about eight or ten gigs. Alan did the posters for all of them. At one, the backdrop and the side fills were hand-drawn comics of a future cityscape by Dick Foreman, Alan Smith and several other talented comic artists. The gigs were noisy, good fun affairs. We did covers of ‘White Light’ and ‘Children of the Revolution’, there was also a pastiche of ‘Aquarius’ from Hair, sung to the same tune in a Mad magazine opera style that began ‘when the goons come crashing down your doors, or drag you off in unmarked cars’. My favourite gig was the UFO Fair in Abington Park. We played the Rocking Horse (the back room of the Racehorse pub in Northampton), we played Chequers in Wellingborough which is also a pub, we played a couple of outdoor local festivals and we had a fantastic time.

Moore took obvious pleasure crafting lyrics that often feel a little reminiscent of his old Future Shocks: simple, funny, high-concept narratives such as ‘Trampling Tokyo’ (sung by a mournful Godzilla, who’s ‘tired of Trampling Tokyo … Bored to death / When my every breath / Sets the boulevard on fire’) and ‘Me and Dorothy Parker’ (in which the narrator and the noted wit go on a Bonnie and Clyde-style crime spree: ‘We went out with both lips blazing, and a pen in either hand’). Little of this material was released at the time, but fifteen of Moore’s lyrics from various projects, including The Emperors of Ice Cream, were published in Negative Burn between 1994 and 1996, illustrated by a number of comics artists. Moore drew the posters for all the gigs, with Johnson remembering that ‘the one for Easter 93 was my fave. It featured the Pillsbury Dough Boy on a cross and the heading said “rejoice for he has risen”.’

Even with his Image commitments, Moore had time to work on his ‘more demanding’ writing projects. According to a progress report he issued in the November 1993 issue of Wizard (the best-selling comics news magazine, rather than the trade journal of his future vocation), he’d just finished Chapter Eight of From Hell and the first book of Lost Girls. It would be a ‘long time’ before Voice of the Fire was completed, but he had it all mapped out. As for Big Numbers, Moore asserted: ‘It is the most advanced comic work I’ve ever done in terms of the storytelling. I’m committed to it – I’ve never left a project unfinished yet, although I can’t draw it myself. If I thought I could I would go for it …’ The interview was conducted just before Moore’s fortieth birthday, and there’s no trace of an interest in magic in it. He describes Voice of the Fire in conventional genre terms – ‘it’s not quite fantasy, but there are certain fantastical elements in it’ – and volunteers to the interviewer that what ‘excites me as an artist’ is ‘the sense that you can make a difference in comics’.

The announcement that Moore had become a magician took even those who knew him best by surprise. Yet by his own account it had been brewing for at least a couple of years.

In a long interview for The Comics Journal conducted by Gary Groth in 1990, Moore had taken the opportunity to talk about politics and philosophy at some length. Confessing, ‘I’ve got a very, very broad, almost functionally useless, definition of art: just as anything which communicates creatively … but I think you’ve got to have a broad definition …’ he had concluded, ‘there is only one organism that is human society or human existence. We’ve divided it up in our reductionist way into different areas of spirituality, sexuality politics, religion, all of these things, but essentially, we’re talking about one thing, one organism.’ While that sounds a little New Agey, he had little time for mysticism as commonly practised, but understood the impulse: ‘New Age mysticism seems to me to be quite dippy and stupid a lot of the time … there are numbers of people out there who in however a muddled and woolly a way are looking for something of substance in their lives.’

Moore was working on the script for Big Numbers #4 at the time. One theme of that book was that people’s lives are controlled by numbers, from everyday things like phone numbers and timetables, via demographics and high finance, right through to the mathematical structures that govern reality. Immersing himself in research, he read books like James Gleick’s Chaos, Rudy Rucker’s Mind Tools and The Fourth Dimension and How to Get There, and Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach and Metamagical Themas. The early nineties saw a vogue for fractals and chaos theory, and both fascinated Moore, as well they might: his work had always relied on pattern, symmetries, echoes, interwoven narratives, entangled events that only appeared to be random. Now he found that much of his work already conformed to the concepts described in the books he was reading, such as the emergence of deep complexity from very simple processes and the huge, unforeseeable consequences of tiny events. Fractal mathematics, Moore felt, dictated that ‘there is order in the world, but it also says that that order does not care about us … we can’t regulate chaos, we can’t impose our will upon the world in the way that we’ve been previously trying to … it’s simply not true that the world is there for man to impose his will on’. He felt that society could be described using this new maths, that we were approaching ‘a boiling point and what comes after the boiling point will be radically different to whatever came before’.

Moore was also working on From Hell, and finding the research equally immersive. He and his artist, Eddie Campbell, would frequently uncover some odd coincidence: ‘There were an awful lot of surprises. They were strange little things that probably wouldn’t mean anything to anybody who hadn’t been obsessively absorbed in all this stuff for the past eight years.’ He noted that one Ripper murder had been carried out close to both Brady Street and to an establishment called Hindley’s – resonant names because Ian Brady and Myra Hindley were notorious serial killers from the 1960s. ‘Like I say, if those first initial impressions are accurate enough, then everything that you subsequently discover will fit in, in some way. It’s quite an eerie process, but it’s one that I’ve found on numerous occasions and in From Hell, that was very definitely true. So there were no real surprises.’ The last sentence of that quote contradicts his opening comment, but not irrevocably. As Moore said, he was immersed in the material, engaging his imagination and looking for patterns. As he had learned with Watchmen, the deeper his research, the more odd pre-existing connections and facts he found to support his instincts. It wasn’t, in other words, a surprise that he found surprises. ‘I was constantly unnerved and amazed by the amount of confirming “evidence” that turned up to support my “theory”, precisely because I knew it wasn’t a theory: it was a fiction. This is a much more strange and wonderful phenomenon than simply being able to say, “I was right all along! William Gull was Jack the Ripper!”.’

While writing Chapter Four of From Hell in early 1991, Moore had found himself putting in the mouth of a man of science, William Gull, words about the divine:

Writers often talk about how their characters or stories become independent of them, saying or doing things that hadn’t occurred to their creator, and this was an example. When Moore read it back to himself, he found that ‘Having written that and been unable to find an angle from which it wasn’t true, I was forced to either ignore its implications or change most of my thinking to fit around this new information.’ That the words were coming out of the mouth of the man From Hell identifies as Jack the Ripper seemed to inspire rather than concern him. As Moore saw it, Gull was ‘quite aware that he is going mad, but that was what he wanted to do. He saw madness as a gateway to a different sort of consciousness’. When Gull talks to himself later in the chapter, ‘Gull the doctor says “Why, to converse with Gods is madness” … And Gull, the man, replies, “Then who’d be sane?”’

Back in 1988, Moore had started with the idea of simply writing ‘some sort of reconstruction of a murder as a graphic novel’ and alighted on the Jack the Ripper case. Now he began to understand that the power of the Ripper story came from the mystery, the legend, the historical context, the conspiracy theories – above all else from a quest to impose meaning on it. One of his inspirations was the title of Douglas Adams’ novel Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency (1987). When, like Adams, he realised that a holistic detective would have to take everything into account, every ‘trivial’ nugget of fact and ‘incidental’ detail, the scope of his enquiry into the murders expanded considerably:

we start out with the murder of five people in London. A well-known murder that took place in the late 1880s in London. Now from that we find that there are threads of meaning that stretch back as far back as say the Dionysiac architects of ancient Crete, that stretch into the architecture of London and London’s history. That stretch into all these different areas of society and privilege that run all the way up to the twentieth century … the whole system is connected and you can start at any point and from there you will find this radiant web of connections that sort of spans everything.

From Hell Chapter Four was written in the first half of 1991, so more than two years were to pass between Moore’s initial insights and the declaration that he was a magician. Having already become fascinated by the question he, along with every other creator, was asked most frequently – ‘where do you get your ideas from?’ – his natural instinct, in line with Brian Eno’s philosophy, was not to be scared of examining his own creative process, but instead to interrogate it: ‘Brian Eno is one of my biggest influences. He had no respect at all for all that precious mystique of music. He’s got a purely mechanical approach to art and craft. He said, in effect, “There are hard scientific principles at work here. If you look at them you can work out what they are and you can use them”.’

He had already undergone such a process of self-examination in 1985, in his essay On Writing for Comics, where he had given a prosaic answer: ‘I’d probably say that ideas seem to germinate at the point of cross-fertilisation between one’s artistic influences and one’s own experience.’ A couple of years after that, he had been scathing of anyone who wasn’t equally pragmatic: ‘I really have no time for this big mystique of art. I think that’s a lie. I think that a lot of artists will try to pretend that they exist in some state of cosmic crushing misery that the rest of the human race can not possibly appreciate and that is just simply bullshit. Art is the same as being a car mechanic. It is just purely a matter of application. There is nothing mystical about it at all.’ Now, though, he began to make connections between the mathematics he was researching for Big Numbers and the study of the occult he was making for From Hell. Reading up on linguistics allowed Moore to see that both were systems attempting meta-analysis of the universe – languages. Language was clearly essential to creativity and to consciousness itself.

There’s a fact that Alan Moore recognised sooner than most of his readers: his work in the late eighties was in danger of being stuck in a rut, of becoming sterile, over-calculated. He needed ‘a new way of looking at things, a new set of tools to continue. I know I could not carry on doing Watchmen over and over again, any more than I could carry on doing From Hell over and over again.’ Now he found a name for this different approach, one that would extend his analysis of his working method into a more general theory of how the creative process worked: ‘Beyond the boundaries of linear and rational thinking, a territory that I came to label, at least for my own purposes, as Magic.’

Moore’s interest in magic did not arrive out of the blue. He remembers being fascinated by myths and legends as a child, and recalls that the first book he borrowed from the library, aged five, was called The Magic Island. He often dreamed of gods and the supernatural, and as a teenager this developed into an interest in the occult and Tarot. Back then, he’d written poetry and drawn pictures inspired by H.P. Lovecraft. Moore had later, of course, created the ‘blue collar’ magician John Constantine in Swamp Thing, and Nightjar, the abandoned series for Warrior, had been about a secret war fought between modern-day magicians; he had also experienced a number of odd coincidences and occurrences which he had tended to dismiss – although he was fond of telling the ‘strange little story’ of how he had once ‘met’ his creation Constantine in London. But, until this point, magic had not featured heavily in his professional work – Maxwell was a magic cat in name only.

Steve Moore, however, had long practised magic, and had edited the Fortean Times, a magazine dedicated to reporting the spectrum of strange phenomena (Alan read the magazine and occasionally contributed reviews and letters). Friends like Neil Gaiman were well-read on the subject. While writing From Hell, Moore had begun studying the history of magic and ritual and either discovered or reacquainted himself with mystical artists like Arthur Machen, David Lindsay, Robert Anton Wilson, Austin Osman Spare and Aleister Crowley.

For Moore, ‘magic’ is the name he gives to instances where language can be seen to affect reality; it’s how human consciousness and imagination interact with the world. The principal way in which human beings do this is through art: ‘writing is the most magical act of all, and is probably at the heart of every magical act.’ Fittingly, the most ornate elaboration of his belief system to date has come in comic book form. In the 32-issue series Promethea (1999–2005), with art by J.H. Williams and Mick Gray, the main character, Sophie Bangs, is initiated into the secrets of magic, and her story depicts all sorts of elements that we know are part of Moore’s own experiences.

The artistic unfurling is an essential part of the explanatory process, which means that a quick summary of Moore’s magical belief system can only sell it short. That said, it is possible to break it down into three key components: psychogeography, snake worship and ideaspace.

Psychogeography, as Moore practises it, is a deep exploration of the landscape and history of a specific location – in his words, ‘a means of divining the meaning of the streets in which we live and pass our lives (and thus our own meaning, as inhabitants of those streets)’. The chapter of From Hell that furnished Moore with the line ‘the one place gods inarguably exist is in our minds’ represents a good example of the technique. William Gull directs the cab driver Netley on a tour of London, drawing attention to a number of sights. Some are familiar tourist traps like the Tower of London, St Paul’s Cathedral and Cleopatra’s Needle, and we’re reminded how odd those landmarks are. Gull shows that many of the same symbols, including the Sun and the Moon, recur in the most unlikely places. They complete a circuit of the striking London churches designed by architect Nicholas Hawksmoor in the early eighteenth century. At the climax of his tour, Gull reveals that if you draw lines between the Hawksmoor churches on a map, you construct a ‘pentacle of Sun Gods, obelisks and rational male fire, wherein unconsciousness, the Moon and Womanhood are chained’.

In his annotations, Moore makes no secret that his main source was the poem ‘Lud Heat’ (1975) by the British writer and avant-gardist Iain Sinclair. He was also heavily influenced by Sinclair’s examination of Gull, the novel White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings (1987). Sinclair’s work had been recommended to him by Neil Gaiman, whereupon Moore got in touch with Sinclair and the two men become fast friends. In 1992 – a year before he announced he had become a magician – Moore made an appearance ‘typecast as an occult fanatic’ in The Cardinal and the Corpse, a film made by Sinclair for Channel Four. In the story, he plays a man (in a leather jacket and Rorschach T-shirt) searching for a book by Francis Barrett that he says ‘is a key to the whole city, it’s called The Magus … the key to the city, the Qabalah.’

Moore – unlike Gull – has made it clear he does not believe he is uncovering some existing code put there by some other being, natural or supernatural. The lines exist, but as lines of information:

That is a pattern I have drawn upon existing events, just as a pentacle is a pattern that I’ve drawn over real sites in London. It’s a meaning that I’ve imposed. I suppose what I was trying to say is that history is open to us to cast these patterns and divine from them, if you want. I mean, no, there is no pentacle over London by design. There is no secret society of Freemasons that actually put these sites into a pentacle shape, but those points can be linked up in a pentacle, that means that those ideas, the ideas that those ideas represent can be linked up into a pattern as can events in history, like the events of the Ripper murders.

But there’s an ambiguity when Moore says he is ‘divining’, or when Sinclair talks of ‘dormant energies’ and a ‘grid of energies’ in the London landscape. Is this meant as a figure of speech, or more literally? Sinclair wants it both ways: ‘it was reinvented into London with people like Stewart Home and the London Psychogeographical Association, who mixed those ideas with ideas of ley lines and Earth mysteries and cobbled it together as a provocation, and I took it on from that point.’ In his 1997 performance The Highbury Working, Moore gives a tongue-in-cheek description of the practical work undertaken by his Moon and Serpent group of magicians: ‘think of us as Rosicrucian heating engineers. We check the pressure in the song-lines, lag etheric channels, and rewire the glamour. Cowboy occultism; cash-in-hand Feng Shui. First you diagnose the area in question, read the street plan’s accidental creases, and decode the orbit maps left there by coffee cups, then go to work.’ Whatever the status of this energy, there’s a purely materialist point being made. Like Sinclair, Moore uses psychogeography to draw attention to the history of an area, to map the deep roots of history and culture.

Sinclair’s work continues that of the Situationist movement which flourished in the sixties and has inspired many British radical groups since. Situationism encouraged the exploration of the terrain of a city as an act to reappropriate the landscape from the demands of consumerism and commodification. It’s a conscious response to the process, accelerated in the Thatcher era, of redeveloping old, proud working-class areas into office space and yuppie flats. Sinclair concentrates mainly on the gentrification of the East End of London, Moore on redevelopment in his native town of Northampton. Sinclair would agree with Moore’s line from The Birth Caul that the recent burst of property development represented the ‘final wallpapering of England’.

Psychogeography has also provided the basis for Moore’s prose novels. Voice of the Fire (1996) was built up from short stories, all set in Northampton at various periods from the Neolithic to an autobiographical chapter set the day Moore wrote it. A Grammar, an abandoned novel that was in its ‘early planning stages’ in 1997, followed ‘a sheep track between Northampton and Wales. It’s a drover’s track that existed probably since the Bronze Age and it crosses through a lot of fascinating territory: Shakespeare Country; Elgar Country; the territories of Pender, the last pagan king of Britain; Alfred Watkins, the ley-line visionary’. The forthcoming Jerusalem is in a similar vein.

Moore first publicly declared that he was now worshipping the snake god Glycon in a February 1994 interview with D.M. Mitchell in Rapid Eye, a magazine described by style bible I-D as a ‘heavyweight periodical devoted to documenting apocalypse culture’. An article in Fortean Times stated that Alan Moore ‘was introduced to Glycon by Steve Moore … whereupon they decided to form the Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels’. Other accounts have implied, either accidentally or through ambiguous language, that the encounter with Glycon was an unplanned occurrence during a magic ritual and that Moore only subsequently learned the fascinating, and extremely apt, history of Glycon worship. This is not the case. For at least fifteen years Steve Moore had enjoyed contact with the moon goddess Selene, as Alan would outline in some detail in Unearthing: ‘I found Steve Moore’s relationship with the goddess – largely conducted through ritual and dream – to be both interesting and potentially instructive.’ Alan wanted his own supernatural guide. Although it was unintentional on his part, it would be Steve Moore who found Alan’s god for him. When Steve showed him pictures of a statue of the moon goddess Hecate that had been excavated in Tomis, Alan’s eye was caught by another statue that had been found with it. ‘I can best describe it as love at first sight. This unutterably bizarre vision of a majestic serpent with a semi-human head crowned with long flowing locks of blonde hair seemed in some inexplicable way familiar to me, as if I already knew it from somewhere inside myself, as pretentious as that probably sounds.’ The two then researched this snake god, which they learned was called Glycon.

The name means ‘sweet one’ in Greek (it’s from the same etymological root as ‘glucose’). A snake that uttered prophecies, Glycon was the focus of a second-century cult which attracted the attention of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. The satirist Lucian was personally acquainted with the man running the operation, Alexander of Abonoteichus, and felt him to be as villainous as his namesake, Alexander the Great, was heroic. Lucian goes into great detail about the formation of the cult, describes at some length how Alexander’s prophetic utterances were faked and what he charged people to hear them, and explains that the snake god Glycon was a simple ventriloquist’s puppet. Rather than being discouraged by such fakery, though, Moore embraced it, feeling it would ‘pre-empt the inevitable ridicule by worshipping a deity that was already established as historically ridiculous’. It was only after Glycon passed this thorough background check – if ‘passed’ is quite the right word – that Moore sought contact. ‘If, as I believed, the landscape that I hoped to enter was entirely imaginary in the conventional usage of the word, then it seemed to … not make sense, exactly, but to be appropriate … that I should enlist an imaginary playmate as my guide to it.’

Late on the night of 7 January 1994, Alan Moore and Steve Moore took magic mushrooms, and as they talked about magic, they came to share the experience of meeting the snake god Glycon. Alan had a conversation with the god that lasted ‘at least part of the evening’:

the first experience I had, and this is very difficult to describe, but it felt to me as if me and a very close friend of mine, were both taken on this ride by a specific entity. The entity seemed to me, and to my friend, to be … this second-century Roman snake god called Glycon. Or that the second-century Roman snake god called Glycon is one of the forms by which this kind of energy is sometimes known. Because the snake as a symbol runs through almost every magical system, every religion … At least part of this experience seemed to be completely outside of Time. There was a perception that all of Time was happening at once. Linear time was a purely a construction of the conscious mind … There were other revelations.

A poem Moore would write soon afterwards, ‘The Deity Glycon’, describes an encounter with this ‘last created of the Roman gods … and the idea of a god, a real idea … his belly filled with understanding, jewels and poison’.

‘Alan Moore’s private magical workings with Glycon are, of course, private’, but we can glean some sense of the form his magical activities take from articles Steve Moore has written about Selene, including the publication of a detailed ‘Selene Pathworking’ designed to engineer an encounter with the goddess. Preparation involves ‘relaxation by any preferred method’, ‘deep breathing and mantra’, then the visualisation of a detailed scenario not unlike those found on self-hypnosis tapes (‘all you can see is blackness. Now you visualise a small glowing disc of silver-white light’), but written by the participants beforehand to give a sense of structure, ritual and purpose to the occasion. At first Alan used magic mushrooms as his ‘preferred method’ of relaxation, but he no longer does so:

Back when I was starting out in magic, I probably did an awful lot more mushrooms. I don’t think I’ve done any actual mushroom-based rituals since … end of last year? [1999/2000] … I find that whereas once I would have used drugs to explore all of the various spheres that I explore in Promethea’s Qabalah series – I mean, indeed I did use drugs to explore the lower five sephirot, but above that, I’m using my own mind, I’m using I suppose it’s what you’d call meditation, although it’s exactly what any writer does when they’re trying to get into a story, it’s just that the story in these instances is deeply concerned with these qabalistic states, so getting into the story is almost the same as getting into the state.

A reference by Leah Moore to the postman seeing her father ‘covered in blood and feathers’ was, as we might guess, facetious. Moore has stated, ‘I’m in the unfortunate position of being a diabolist and vegetarian, I’m afraid living sacrifices were out of the question … I have burned objects of meaning and significance to me.’ At various times he has conducted rituals alone, with Steve Moore, with ‘a musician’ (in fact Tim Perkins) and with ‘other magicians’. Moore once showed Brian Bolland his cellar and told him demons had manifested there, but he’s also conducted workings in his living room. Once the ritual is underway, Moore has said he enters a ‘fugue state’ where a ‘disorientating, overwhelming, even terrifying’ amount of information is presented to him and he has to find a path through it. The only way to do that is to lose a sense of ‘self’, so that once the ritual is over ‘recollection of the experience is necessarily non-linear, fragmentary … It’s not that I have any reservations about discussing these matters clearly and lucidly; it’s just that I can’t.’

As for specific encounters, we know that in January or February 1994, Moore ‘had a moment which was right on the very cusp of madness, in which I thought I was Jesus, that I thought I was the messiah and had come to lead the world out of darkness and into light. I thought “well, it’s hardly surprising. I always knew I was a special, lovelier-than-average person. It only makes sense that Jesus would turn out to be someone fabulous like me.’ Then, luckily, a more sane part of me moved in and said “Focus, you cunt! You’re not Jesus – this energy is Jesus – the Christos”.’

A line in Promethea #12 (February 2001) that ‘initiation may be a dark and dangerous ride, a journey through the land of shade required before progress is made’ suggests Moore’s early experiences were not all pleasant. We know that something of the kind happened ‘about a month’ after the initial encounter with Glycon (again, then, February 1994):

I also had an experience with a demonic creature that told me that its name was Asmoday. Which is Asmodeus. And when I actually was allowed to see what the creature looked like, or what it was prepared to show me, it was this latticework … if you imagine a spider, and then imagine multiple images of that spider, that are kind of linked together – multiple images at different scales, that are all linked together – it’s as if this thing is moving through a different sort of time. You know Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase? Where you can see all the different stages of the movement at once. So if you imagine that you’ve got this spider, that it was moving around, but it was coming from background to foreground, what you’d get is sort of several spiders, if you like, showing the different stages of its movement.

Moore noted that Asmodeus spoke ‘with great politeness and charm’. Unlike Glycon, Moore says, he only did his research into Asmodeus after encountering him, although we know he was previously at least aware of the name, as it had appeared in one of his very first published pieces. The third stanza of the poem ‘Deathshead’ in Embryo #2 (December 1970) runs:

I told you the words

That might call up Asmodeus

I wrote out the score

For the ghosts of Japan

He would later depict Asmoday in Promethea as a malevolent, fearsome force.

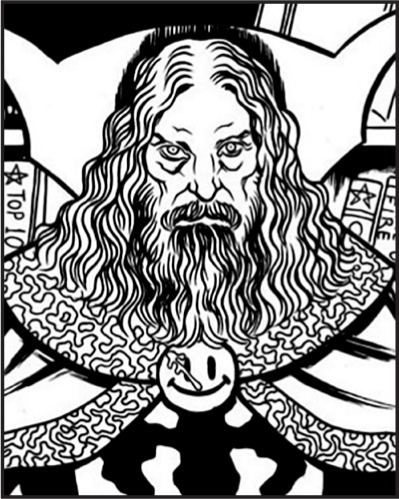

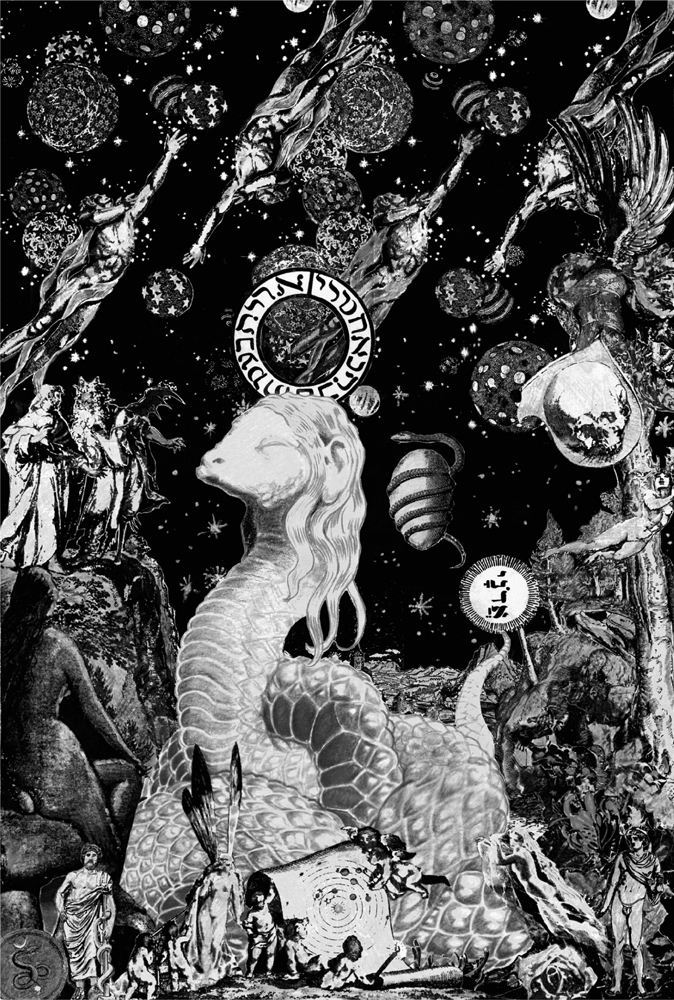

These early magical experiences inspired a burst of creativity from Moore as he attempted to assimilate and describe them. He created a picture of Glycon, which he named The Garden of Magic; or, the Powers and Thrones Approach the Bridge (see next page).

Within a week of his first encounter with the god, he had written two songs, ‘The Hair of the Snake That Bit Me’ and ‘Town of Lights’. The first of those begins ‘Step up now, Gentlemen and Ladies, come this way here in the Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels’, and soon afterwards, an actual organisation of that name ‘tumbled into existence, a fictional freakish sideshow alluded to in the song lyric that somehow seemed to be begging to be brought to some kind of peculiar life’.

The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels consists of Alan Moore, Steve Moore, Tim Perkins, David J, John Coulthart and Melinda Gebbie, but it’s an extremely loose ‘organisation’ and doesn’t have initiation rituals or, indeed, any formal structure, to the point that it ‘doesn’t actually exist in the conventional sense’. The participants came up with a fake history for the society dating back centuries, a parody of secret societies such as the Rosicrucians and Masons which are associated with similar claims. The ‘moon’ and ‘serpent’ are, respectively, Selene and Glycon.

When the journalist D.M. Mitchell interviewed Moore in February 1994, he managed to capture some of Moore’s initial disorientation at his experiences: ‘This is all very new to me. I’ve been receiving some kind of bargain basement apotheosis, and my head’s still spinning. Probably in a few months I’ll be able to talk about this more calmly and more coherently.’ Mitchell knew Moore had begun a new book, Yuggoth Cultures, a collection of poetry and prose pieces based on the works of H.P. Lovecraft, because it had grown from a short story commission for Mitchell’s anthology The Starry Wisdom. Though Moore had been interested in Lovecraft since he was thirteen, he told Mitchell: ‘I have recently seen him in a different light.’ This was surely because Moore had been reading the works of Kenneth Grant, the occultist appointed – at least according to Grant – by Aleister Crowley as his successor. Grant asserted that Lovecraft’s tales of Great Old Ones ‘represented valid channels of magical information’. But Moore claims to have abandoned writing Yuggoth Cultures after he left the manuscript in a taxi, and there’s supporting evidence that this is more than just a tall tale: he mentioned the book in his Rapid Eye interview, and it was advertised and assigned an ISBN number. In the event, the surviving fragments, barely a few hundred words long, were printed in the anthology itself titled Yuggoth Cultures.

The two songs Moore had written became the opening and closing numbers of the new group’s first performance piece, also called The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels, which was staged around seven months after his first magical encounter, on 16 July 1994. It was intended as a one-off: as a child, Moore had seen the comedian Ken Dodd perform, and had been struck during the performance that Dodd performed the same jokes night after night, that the spontaneity and intimacy with the audience was an illusion, and that he could have almost exactly the same experience again just by going back the next night. Each of the Moon and Serpent’s workings has in contrast been specific to the time and location: in this case, it was the night the comet Shoemaker-Levy impacted Jupiter, one of the more spectacular astronomical events of the twentieth century. Moore and his colleagues intended it as a public magic ritual, taking the form – in a clear echo of his old Arts Lab days – of a multimedia performance that would engage the audience in an immersive, rich blend of music, monologues, dance and poetry.

The piece laid out the basics of Moore’s cosmology, sketched in some background details, and depicted magical experiences which were presumably very close to his own. The performance began with the ‘roll up, roll up’ call of ‘The Hair of the Snake That Bit Me’, moving on to ‘The Map Drawn on Vapour (I)’, where Moore set down some of the basics of the associative nature of Ideaspace, and related it to his own experience with Iain Sinclair and psychogeography. This was continued in ‘Litvinoff’s Book’, which discussed East End gangsters, before segueing into ‘A Map Drawn on Vapour (II)’, virtually a recap of Gull’s tour of London in From Hell. From there, Moore moved to a more transcendental realm. ‘The Stairs Beyond Substance’ discussed quantum physics and the limits of knowledge, then ‘The Spectre Garden’ plunged into three poems about encountering gods: ‘The Enochian Angel Of The 7th Aethyr’, ‘The Demon Regent Asmodeus’ and ‘The Deity Glycon’. The final act was ‘The Book of Copulation’, a long poem that built to a crescendo, asserting that we are all – every person, every supernatural entity – aspects of one being. The song ‘Town of Lights’ was a coda, telling us that there are angels within us and Jerusalem is in sight.

It was performed as part of a three-evening event hosted by Iain Sinclair which attracted a ‘surprisingly small’ audience. A backing tape composed by David J and Tim Perkins played in the background. Perkins didn’t attend, but ‘David J mimed, mummed and performed enigmatic symbols at the stage periphery – Ariel to Alan’s Prospero’. Melinda Gebbie provided the voice of an angel. Moore left the stage to applause from the audience, then circulated to gauge reaction, which was positive.

A transcript was published in the fanzine Frontal Lobe, and the lyrics for a number of the songs appeared over the next few years in Negative Burn. Shortly afterwards, Moore rerecorded his part in a studio and it was mixed with the existing backing tapes by David J and Perkins for eventual release on CD (2001). A photograph taken during rehearsal that apparently showed a spectral figure standing behind David J, beaming energy or ectoplasm at Moore, was published in Fortean Times, alongside the Rapid Eye interview and on the CD sleeve.

A little dissatisfied with that first ‘working’ and painfully aware he was finding it difficult to describe his experiences, Moore ‘switched to a more analytical mode’ and began to assemble a large library of books about magic and the history of the occult, as well as grimoires and artefacts of magical significance.

But does he really believe that Glycon and Asmodeus exist? Inarguably, we have to accept that they exist inside Alan Moore’s head. And once we’ve accepted that, we can move on to the meat of his argument: psychogeography and veneration of Glycon are methods Moore uses to explore Ideaspace.

When he first started his research, Moore had been surprised to discover that there wasn’t ‘much of a theory to make sense of any sort of consciousness’. Moore is committed to the scientific worldview. He believes that magicians and occultists have tended to make a fundamental mistake in seeing magic as a rival scientific system with strict ‘laws’. Magic, for Moore, is an art, albeit a ‘meta-art’ akin to psychology or linguistics, and, in his view, virtually all great art has been created by artists with magical beliefs of one kind or another. Science, however, has at least one serious limitation: it ‘cannot discuss or explore consciousness itself, since scientific reality is based entirely upon empirical phenomena’, and so ‘if I wanted a working model of consciousness that would be of any use to me personally or professionally, it became clear that I’d have to build it myself’.

The entire middle section of Promethea is an extended journey into Ideaspace – called the Immateria in the comic – the ‘magical realm’. The series is essentially a lyceum lecture in which Moore reports on some of the places he’s explored. In #11 (December 2000), the title character’s words can easily be imagined as an echo of Moore’s own thoughts back in the early nineties: ‘I feel a need to take a long journey soon, to find someone. A journey into magic. I’ve read a lot of books, I understand the ideas intellectually, I suppose, but I don’t really feel them … I need to understand it from inside.’ Promethea carries a staff, a twin-snake-headed caduceus (Moore had taken to carrying a walking cane topped with a carved snakehead). The snakes start to talk to her. They are Mack and Mike (short for ‘macro’ and ‘micro’), and she consistently fails to tell them apart. They talk in rhyme, and paint a picture that Moore’s regular readers would recognise from ‘The Hair of the Snake That Bit Me’:

to enter magic, in a sense,

means entering our intelligence.

That record-breaking smash-hit show,

the theatre of what we know,

where thoughts parade in fancy dress

upon the stage of consciousness

The next issue, Promethea #12 (February 2001) is one of the most extraordinary entries in Moore’s canon. It is a survey of how the history of the universe is underpinned by magic, with an emphasis on the development of human culture. Each page is a variation of the same ornate single panel and each depicts Promethea considering a different Tarot card, each card being drawn as a cartoon character. Mack and Mike give their interpretation of the cards, still talking in rhyme. Scrabble tiles spell out apt anagrams of the word ‘Promethea’ (so the chapter as a whole is called ‘Metaphore’, and on the page where sex is discovered, the tiles read ‘Me Atop Her’). Running along the bottom of the pages, Aleister Crowley takes the whole issue to tell a joke, while we see him age from embryo to skeleton. There are recurring design elements, including a chessboard pattern across the top of each page and a cartoon devil and angel that appear on alternate pages. Moore is never afraid to make it clear how clever he’s being, or of deploying puns. At one point, Promethea is overwhelmed by the mass of information, and in her confusion comments on the joke Crowley is recounting instead of the Tarot card: ‘“railway carriage”, are you sure that’s part of this train of thought?’ – I’m sorry, I’m having trouble keeping the different threads separate. I’m not even sure which of you two is which.’ The snakes on her staff inform her (and us), ‘it’s like a fugue, you have a choice of following a single voice, or letting each strand grow less clear, the music of the whole to hear’.

Subsequent issues are equally elaborate. As comics critic Douglas Wolk notes, Moore was clearly ‘emboldened by the fact that Williams and Gray’s hands hadn’t strangled him’.

Moore interprets the universe as a four-dimensional solid containing past, present and future which we explore using our consciousness. Within our heads, we have an individual mental landscape – Ideaspace – that fits together associatively. An example Moore is fond of giving is that Land’s End and John O’Groats are close together in Ideaspace – they are conceptually close precisely because they’re proverbially far apart. Ideaspace is organised into areas governed by certain principles, such as Judgement. The first explorers to discover the ‘shifting contours’ of Ideaspace were shamans, who used hallucinogenic drugs to enter the realm of the imagination and so were able to guide the rest of early humankind. This tradition has continued and developed; in more recent times occultists have drawn up maps like the Tarot and Qabalah which, if used correctly, can function as allegories for the entire possible range of human experience. Moore believes magic is central to art, indeed that language itself was originally a system of signs and symbols designed to explain what the shamans were encountering.

Some of these symbols frequently recur. The Serpent is one: the ‘lifesnake’, Will, male principle, or phallus – the ‘snake energy’ known to many of the world’s belief systems in the form of snake gods (including Glycon). This symbol is often associated with gold, and is ultimately a representation of the double helix of DNA. Another symbol is the Moon: the imagination, dreams, the feminine principle, often personified as a goddess (like Selene), and associated with silver. The dream world, the underworld and the land of the dead are all the same place, and governed by the Moon. The joining of the male and female principle – will and imagination – is the origin of creativity. Sex is a metaphor/avatar/example of this. The interplay between life and imagination originates the Theatre of Marvels: the universe.

Moore’s personal experiences have led him to believe his Ideaspace is connected to that of others, so it may be something like Jung’s collective unconscious. Ideaspace is not neutral or inert, there are clear indications it has awareness, an agenda, and a sense of humour. The gods live in Ideaspace, Ideaspace is contained within our minds, so we all contain gods. Angels are our highest drive, devils our lowest impulses. ‘There are angels in you.’

Moore makes no secret of the fact that his worldview is a synthesis of his research and experience. In Promethea #10 (October 2000), Sophie is given a pile of books to read before her entry into the Immateria (‘Crowley’s Magick Without Tears and 777, plus some other stuff. Eliphas Levi’). Broadly speaking, he is offering a reinterpretation of Crowley’s cosmology, with reference to author and philosopher Robert Anton Wilson, and artist and occultist Austin Osman Spare. This is counterbalanced by insights gleaned from a voracious reading of books about quantum physics, genetics, mathematics and computer science by writers like Rudy Rucker, Stephen Hawking and Richard Dawkins. The conclusion of the Moon and Serpent performance is almost a direct quotation from Joseph Campbell, who asserted (via Jung), ‘All the gods, all the heavens, all the worlds, are within us. They are magnified dreams, and dreams are manifestations in image form of the energies of the body in conflict with each other. That is what myth is. Myth is a manifestation in symbolic images, in metaphorical images, of the energies of the organs of the body in conflict with each other.’ It’s clear from Moon and Serpent that the basics of this belief system had been worked out/revealed to Moore in his first few months as a magician. That said, he has also picked up new ideas along the way. As he wrote in one essay, ‘The Serpent and the Sword’, the idea that snake symbolism in mythology represents DNA came from The Cosmic Serpent, by the anthropologist Jeremy Narby (first published in English in 1998). Moreover, he accepts Narby’s theory that DNA stores information, and believes some DNA – possibly so-called ‘junk DNA’ – acts as a storehouse of ancestral knowledge which can be accessed using ritual.

Although Moore might have claimed that his initiation into magic represented (my emphasis) ‘a major sea change. It has opened up different sorts of perceptions. I still have access to all my old perceptions, but I have a range of new ones now as well,’ it’s hard to find anything truly new in his work after his encounter with Glycon. Moore’s Road to Damascus moment didn’t lead to a radical rethink. He did not wake up the next morning, embrace the material, shave off his hair and decide to see the world. Everything that followed can be seen as an extension of his previous beliefs and concerns. His narrative techniques remain similar. The grand survey of human history we see in Promethea is reminiscent of V’s televised address or The Mirror of Love. He’s still telling stories full of symmetries and creating comic strips where the last panel leads neatly back to the first, he’s still making heavy use of puns and similar wordplay, and his writing still has the same distinctive rhythm, what Douglas Wolk called ‘an iambic gallop: da-dum, da-dum, da-dum’. For that matter, the tone of ‘Fossil Angels’, a 2002 essay exhorting existing magicians and followers of the occult to abandon their twee clichés, is very similar to the articles he wrote in the early eighties bemoaning the laziness of comics creators who still relied on Stan Lee’s template. Once again, he sees untapped potential in the medium, held back by nostalgia and by unimaginative people who’ve forgotten the original, primal power of the stories modern practitioners merely ape.

The message he drew from contact with higher powers wasn’t quite ‘steady as she goes’, but it did act as a reaffirmation of his existing beliefs, giving him new energy to pursue the themes he was already exploring.

There are also very similar concepts present in his earlier work. Promethea’s Immateria, a glittering web of interconnected life and shared consciousness, strongly resembles depictions of ‘the Green’ in Swamp Thing, both in terms of their conception and in the way Moore represents them on the page. And in Snakes and Ladders, Moore wrote of a second encounter with John Constantine: ‘Years later, in another place, he steps out of the dark and speaks to me. He whispers: “I’ll tell you the ultimate secret of magic. Any cunt could do it.”’ Moore clarified in the documentary The Mindscape of Alan Moore that this encounter took place during a magic ritual; he either hasn’t noticed, or has chosen not to draw attention to, a scene from the beginning of Book Two of The Ballad of Halo Jones, written fifteen years before, around the time he created Constantine. In it, we learn details of Halo Jones’ epic journey out into the universe (some of which foreshadow events beyond the end of the published series) – ‘she saw places that aren’t even there any more!’ And we learn her most memorable quotation: ‘Anybody could have done it’.

There’s more. When Moore says, ‘I think that if magic is anything, it’s about realising the unbelievable supernatural magic’ – those words being spoken in a stage whisper – ‘is in just the fact that we are thinking and having this conversation. Realising just how magical every instant is, every drawn breath, every thought. Just how astronomical the odds are against it. How wonderful. And following through these kinds of beautiful chains of symbols that can lead to some interesting revelations,’ it’s hard not to hear an echo of Dr Manhattan:

thermodynamic miracles … events with odds against so astronomical they’re effectively impossible, like oxygen spontaneously becoming gold. I long to observe such a thing. And yet, in each human coupling, a thousand million sperm vie for a single egg. Multiply those odds by countless generations, against the odds of your ancestors being alive; meeting; siring this precise son, that exact daughter … until your mother loves a man she has every reason to hate, and of that union, of the thousand million children competing for fertilization, it was you, only you that emerged. To distill so specific a form from that chaos of improbability, like turning air to gold … that is the crowning unlikelihood. The thermodynamic miracle…. but the world is so full of people, so crowded with these miracles that they become commonplace and we forget … I forget. We gaze continually in the world and it grows dull in our perceptions. Yet seen from another’s vantage point, as if new, it may still take the breath away.

Moreover, Moore’s observation that ‘if there is truly no linear time as we understand it, then the events that make up the vast hyper-solid of existence can be read with as much validity from back to front as from front to back’, is a lesson Dr Manhattan had already learned. And when he goes on to say ‘our lives are as “true” if we view the film in reverse. In this reading of the world, our inert bodies are dug up from the ground or magically reassembled in the inferno of a crematorium oven’, he is echoing precisely the sequence of events depicted in a 2000AD Future Shock, ‘The Reversible Man’. Back in 1985, he’d even described a method of plotting a story that sounds like Promethea navigating the Immateria: ‘establish your continuum as a four-dimensional shape with length, breadth, depth and time, and then pick out the single thread of narrative that leads you most interestingly and most revealingly through the landscape that you’ve created, whether it be a literal landscape or some more abstract and psychological terrain.’

There is, too, a distinct sense of landscape in Swamp Thing’s Louisiana, and even something psychogeographical in Rorschach’s declaration ‘This city is afraid of me … I have seen its true face.’ But Moore’s ahead of us: ‘One of the perceptions I had bore relevance to my previous work; especially to Watchmen (the Dr Manhattan chapter) and a couple of the time travel stories I wrote for 2000AD. In the burning white heart of the experience, I thought I had a revelation that those stories were premonitions of the state that I exist in now. Time can be seen just as effectively one way as another. The Dr Manhattan material was a “memory” of the state I’m in now in 1994 – a “memory” which persisted until 1985.’

So, what are we to make of all this? It’s paraphrasing only very slightly to say that Alan Moore has consulted the contents of his own head and concluded that everything in our culture, including language and art, arose from bearded shamans who were fond of magic mushrooms and expressed their message in obscure, coded picture writing. Indeed, the world would be a much more chilled place if everyone would just listen to their modern-day equivalents. Oh, and those guys give really great orgasms. Whatever else it is, Moore’s view of the world is inescapably self-indulgent.