There was a vague understanding among the members of the Cabala that I was engaged upon the composition of a play about Saint Augustine. None of my friends had ever seen the manuscript (even I was surprised to come upon it every now and then at the bottom of my trunk), but it was treated with enormous respect. Mlle. de Morfontaine especially kept asking about it, kept walking about on tiptoes and glancing at it sideways. It was to this that she was alluding in the note I received soon after Blair’s frightened departure: Try and arrange to come up to the Villa for a few weeks. It is perfectly quiet until five o’clock every afternoon. You can work on your poem.

It was my turn for a little peace. I had so recently passed through the desperations of Marcantonio and Alix. I sat holding the note for a long while, my wary nervous system begging me to be cautious, begging me to make sure that no hysterical evenings could possibly lie behind it. Here was a place where it was perfectly quiet until five o’clock every afternoon. It was five o’clock every morning that I wanted to be reassured about. You can work on your poem. Surely the only vexation that could proceed from that wonderful lady lay exactly there,—she would be asking me every morning about the progress on the Third Act. It would be good for me to be hectored about my play. And what wonderful wines she stored. To be sure the lady was mad, indubitably mad. But mad in a nice way, with perfect dignity; decently mad on a million a year. I wrote her I would come.

What could have been more reassuring than the first days? Mornings of sunlight when the dust settled thicker on the olive-leaves; when the terraced hillside seemed to be powdering away; when no sound reached the garden but the cry of a carter in the road, the cooing of doves, stepping high along the eaves of the gardener’s shed, and the sound of the waterfall with its mysterious retardations, a sound of bronze. I ate luncheon alone under a grape arbor. The rest of the day was spent in roaming over the hills or among the high chairs of Astrée-Luce’s rich and curious library.

From the middle of the afternoon one sensed the approach of dinner. One felt the gradual tightening of the chord of formality until, like the bursting of some pyrotechnical bomb, full of dazzling lights and fascinating detail, the ceremony began. For hours there had come a hum as of bees from the wing of the house that contained the kitchen; there followed the flights of maids and hairdressers through the corridors, the candle-lighter, the flower-bearers. The crushing of gravel under the window announces the arrival of the first guests. The majordomo clasps on his golden chain and takes his place with the footmen at the door. Mlle. de Morfontaine descends from her tower kicking her train about to teach it its flexibility. A string quartet on the balcony begins a waltz by Glazounov as subdued as a surreptitious rehearsal. The evening takes on the air of a pageant by Reinhardt. One passes to the saloon. At the head of the table behind peaks of fruits and ferns, or cascades of crystal and flowers, sits the hostess, generally in yellow satin, her high ugly face lit with its half-mad surprise. She generally supports a headdress of branching feathers and looks like nothing so much as a bird of the Andes blown to that bleakness by the coldest Pacific breezes.

I have described how Miss Grier brooded over her table and placed herself to hear every word whispered by her remotest guest. Astrée-Luce followed a contrary procedure and heard so little of what was said that her very guest of honor was often obliged to resign all hope of engaging her attention. She would seem to have been caught up into a trance; her eyes would be fixed on some corner of the ceiling as though she were trying to catch the distant slamming of a door. Generally some Cabalist held the opposite end of the table: Mme. Bernstein, huddled up in her rich fur cape, looking like an ailing chimpanzee and turning from side to side the encouraging amiability of her grimace; or the Duchess d’Aquilanera, a portrait by Moroni, her dress a little spotty, her face a little smudged, but somehow evoking all the passionate dishonest splendid barons of her line; or Alix d’Espoli making passes with her exquisite hands and transforming the guests into witty and lovable and enthusiastic souls. Miss Grier seldom came, having festivals of her own to direct. Nor was it often possible to invite the Cardinal, since any company to meet him must be chosen with infinite discretion.

Almost every evening after the last guest had left the hill or retired to bed, and the last servant had finished finding little things to adjust, Astrée-Luce and I would descend into the library and have long talks over a drop of fine. It was then that I began to understand the woman and to see where my first judgments had been wrong. This was not a silly spinster of vast wealth nourishing a Royalist chimaera; nor the sentimental half-wit of the philanthropic committees; but a Second-Century Christian. A shy religious girl so little attached to the things about her that she might awake any day and discover that she had forgotten her name and address.

Astrée-Luce has always illustrated for me the futility of goodness without intelligence. The dear creature lived in a mist of real piety; her mind never drifted long from the contemplation of her creator; her every impulse was goodness itself: but she had no brains. Her charities were immense but undigested; she was the prey of anyone who wrote her a letter. Fortunately her donations were small, for she lacked the awareness to be either avaricious or prodigal. I think she would have been very happy as a servant; she would have understood the role, have seen beauty in it, and if her position had been full of humiliation and trials it would have deeply nourished her. Sainthood is impossible without obstacles and she never could find any. She had heard over and over again of the sins of pride and doubt and anger, but never having felt even the faintest twinge she had passed through the earlier stages of the spiritual life in utter bewilderment. She felt sure that she was a wicked sinful woman, but did not know how to go about her own reform. Sloth? She had been on her knees an hour every morning before her maid appeared. So difficult, so difficult is the process of making oneself good. Pride? At last after intense self-examination she thought she had isolated in herself some vestiges of pride. She attacked them with fury. She forced herself to do appalling things in public in order to uproot the propensity. Pride of appearance or of wealth? She soiled her sleeves and bodice intentionally and suffered the silent consternation of her friends.

She read the lessons so literally that I have seen her give away her coat time after time. I have seen her walk miles with a friend who asked her to go as far as the road. Now I was to learn that her fits of abstraction were withdrawals into herself for prayer and adoration, and often caused by almost ludicrous incidents. I was no longer left to wonder why all references to fish and fishing sent her off into the clouds; I realized that the Greek word for fish was the monogram of her Lord and acted upon her much as a muezzin’s call acts upon a Mohammedan. A traveller spoke flippantly of the pelican; at once Mlle. de Morfontaine repaired to her mental altar and besought its guest not to grieve at the disrespect paid to one of His most vivid symbols. Strangest illustration of all was shown me a little later. One day she chanced to notice on my hall table an envelope which I had addressed to Miss Irene H. Spencer, a teacher of Latin in the High Schools at Grand Rapids, who had come over to put her hand on the Forum. At once Astrée-Luce insisted on meeting her. I never told Miss Spencer why she had been tendered so amazing a luncheon, why her hostess had listened so breathlessly to her trivial travelogues, nor why on the following day a golden chain hung with sapphires had been left at the pension for her. In fact Miss Spencer was a devout Methodist and would have been shocked to learn that IHS meant anything.

Strange though Mlle. de Morfontaine was, she was never ridiculous. Such utter refusal of self can by sheer excess become a substitute for intelligence. Certainly she was able to let fall remarkably penetrating judgments, judgments that proceeded from the intuition without passing through the confused corridors of our reason. Though she was exasperating at times, at others she would abound in almost miraculous perceptions of one’s needs. People as diverse as Donna Leda and myself had to love her, one moment almost with condescension as to an unreasonable child, and the next with awe, with fear in the presence of something of infinite possibility. Whom were we entertaining unawares? Might this, oh literally! be an . . .?

This then was the being whom I came to know during those late conversations in the library over a drop of fine. The talk was leisurely, full of pauses and to no point, but my bruised instinct could no longer escape the conviction that there was some deeply important matter that she wished to submit to me. I soon foresaw that I was not to rest. My dread of the revelation however was heightened by the obvious difficulty Astrée-Luce found in coming to the point. Finally instead of trying to avoid the discussion I tried to provoke it; I thought I could help here and there by opening veins of conversation that might surprise her problem. But no. The happy moment hung off.

One evening, she asked me abruptly whether it would greatly interfere with my work if we were to move to Anzio for a few days. I replied that I should like nothing better. All I knew of Anzio was that it was one of the resorts on the sea, a few hours from Rome, the site of one of Cicero’s villas, and near Nettuno. She added a little anxiously that we should have to go to a hotel, a very poor hotel at that, but that it was out of season and there were ways in which she could supply some of the deficiencies of the service. A little foresight could prevent my being too uncomfortable.

So one morning we climbed into the large plain car she reserved for travelling and drove westward. The back seat served as a warehouse. One glimpsed a maid, a prie-dieu, a cat, a real panel by Fra Angelico, a box of wines, fifty books and some window curtains. I found out later that there had been a lavish assortment of caviare, pâté, truffles and ingredients for rare sauces by which, with a discouraging failure to understand me, she intended to supplement the resources of a tourists’ hotel. She drove, herself, and in nothing did Heaven’s interest in her reveal itself more clearly. First we stopped at Ostia so that I might see the veritable spot where the last scene of my wretched play took place. We read aloud the page of Augustine and I silently vowed to renounce forever any notion of rephrasing it.

On our first evening at Anzio a cold wind blew in from the sea. The vines and shrubs whipped the houses; the lamps of the cafés about the square swung cheerlessly over wet tables; one could not escape the desolate slip-slap of the waves against the sea-wall. But we both had a taste for such weather. We decided at about six o’clock to walk to Nettuno returning for dinner at half-past nine. We wrapped ourselves in rubber and started off, leaning against the wind and spray and feeling strangely exhilarated. For a time we walked in silence, but entering at last that portion of the road that lies between the high walls of the villas, Astrée-Luce began to talk:

I have told you before, Samuele (the whole Cabala had followed the Princess in calling me Samuele), that the hope of my life is to see a king reigning in France. How impossible such a thing seems now! No one knows it better than I. But everything I love most is improbable. And it is the fact that it seems so untimely that will help us most when we come to prepare the Divine Right of Kings as a dogma of the Church. What anger there will be, what sneers! Even important Churchmen will rush down to Rome and beg us not to upset the progress of Catholicism by such a move. There will be controversies. All the newspapers and the reviews will be shouting and weeping and laughing and the whole basis of democratic government, the folly of republics, will be aired. Europe will be cleansed of the poison in its side. We have nothing to fear from debates. The people will turn to God and ask to be ruled by those houses of His choosing.—However, I am not trying to convince you of it now, Samuele; I am only stating it so as to lead up to something else. You are a Protestant; does this make you impatient? Are you tired of me?

No, no, please. I am very interested, I replied.

At that moment our road brought us again to the water’s edge. We stood for a moment on a parapet looking down on the loud sea that plunged about on the washing stones of a village. It began to rain. Astrée-Luce was gripping the iron railing watching the steam that rose from the waves; she was crying silently.

Perhaps, she continued, as we returned to our journey, you can imagine the tenth part of my disappointment as I watch the Cardinal getting older, and myself, and the nations falling deeper and deeper into error, and so little done. He can help us. He seems to me to have been especially created to help us. I do not forget his work in China. It was heroic. But what a greater work remains for him in Europe. Year follows year and still he sits up there on the Janiculum, reading and walking in the garden. Europe is dying. He will not stir.

At the time I was deeply moved. The rain and her tears and the puddles and the slapping noises of the water against the seawall had begun to affect me. All the voices of nature kept repeating: Europe is Dying. I would have liked to stop and have a good meaningless cry myself, but I had to listen to the voice beside me:

I cannot understand why he does not write. Perhaps I am not meant to understand. I know he believes that the universality of the Church is imminent. I know that he believes that a Catholic Crown is the only possible rule. But he does not stir to help us. All we ask from him is a book on the Church and the States. Think, Samuele, his learning, his logic, his style—but you have never heard him preach? His irony in controversy and his amazing perorations! What would be left of Bosanquet? The constitutions of the republics of the world would be tossed about—you will forgive me if I seem disrespectful to your great country—tossed about like eggshells. His book would not be just a book fallen from the press: it would be a force of nature; it would be the simultaneous birth of an idea in a thousand minds. It would be placed at once in the canon and bound up with the Bible. And yet he spends his day among rose bushes and rabbits and reading histories of this and that. I want to do this in my lifetime; I want to arouse this great man to his task. And you can help me.

I was excited. The air was full of a divine absurdity. Here was someone who was not afraid of using superlatives. This was being mad on a great scale. It would be hard to come down to ordinary living after these intoxicating threats against the presidents of this world and the binderies of the British Bible Society. I tried to think of something to say. I mumbled something about willingness.

She did not notice my inadequacy. It seems to me, she continued, that I have at last discovered one of the causes of his reluctance to join us. But first, tell me how he is regarded by the various Romans whom you have met. What is his legend among people who do not know him?

Here I was frightened. Could she have heard? How could any of those strange rumors have reached her?

But she would learn nothing from me. I took leave of good faith and told her all the favorable reports I had heard. Simple souls were captivated by the thought that apart from a few major obligations he lived on sixty-five lire a week; that he spoke twelve languages; that he enjoyed polenta; that he visited in certain Roman homes (her own, in particular) without ceremony; that he was translating the Confessions and the Imitation into exquisite Chinese. I knew Romans who so loved the very thought of him that they took walks to the Janiculan Hill solely to peer between his garden gates and lurked about the house in the hope of giving their children an opportunity to kiss his ring.

Astrée-Luce waited in silence. At last she said with only a trace of reproach:

You are trying to spare me, Samuele. But I know. There are other stories about him. His enemies have been at work systematically poisoning his prestige. We know that there is no one in Rome who is kinder, more humble, higher-minded; but among the common people he has almost the reputation of a monster. Some people have been at work spreading such rumors deliberately. And the Cardinal has heard of them: through the whispering of servants or by cries in the road, or by anonymous letters, in all sorts of ways. He exaggerates this attitude. He feels that he is in a hostile world. It has made his old age tragic. And that is why he will not write. Yet it is within our power to save him still.—But look! There is a francobollo shop. Let us get some cigarettes and find some place to sit down. It makes me so happy to talk of this!

Provided with cigarettes we looked about for a wine shop. Our wish evoked one at the next curve in the road, a smoky uncordial tunnel, but we sat down before the glasses of sour inky wine and continued our conspiracy. Astrée-Luce confessed that if the ill-odor had become attached to the Cardinal’s name through any real delinquencies on his part, we could not have hoped to dissipate it. Truth in such subtle regions as rumor would be unalterable. But she knew that the aspersions in this case were the result of a clever campaign and she felt sure that a countercampaign could still sweeten his reputation. In the first place our enemies had taken advantage of the Italians’ prejudice against the Orient. An Italian enjoys the same delicious shudder at the sight of a Chinaman that an American boy does at the mention of a trapdoor over a river. The Cardinal had returned from the East yellow, unwrinkled. His walk troubled them. It was easy to build upon this, to pass the whisper along the Trasteverine underworld that he kept strange images, that animals (his gardenful of rabbits and ducks and guinea fowl) could be heard shrieking late at night, that his faithful Chinese servant had been seen in all sorts of terrifying attitudes. Next, his frugal life stirred their imaginations. Every one knew he was fabulously wealthy. Rubies as big as your fist and sapphires like doorknobs, where were they? Did you ever go up to the gate of the Villino Wei Ho? Come with me Sunday. If you sniff hard enough you can get the strangest odor, one that will leave you drowsy for days and give you dreams.

We were to change all this. We sat there choosing a committee of rehabilitation. We were to have magazine articles, newspaper paragraphs. His eightieth birthday was approaching. There would be presentations. Mlle. de Morfontaine was donating a Raphael altar piece to his titular church. But most of all we would send out agents among the people, telling them of his goodness, his simplicity, his donations to their hospitals, and ever so faintly his sympathy with socialistic ideas; he was to be the People’s Cardinal. We had anecdotes of his snubbing the arrogant members of the College, of his defending a poor man who had stolen a chalice from his church. China was to be re-created for the Trasteverines. And so on. We were to prop up the Cardinal so that the Cardinal could prop up Europe.

When we returned to the hotel that night Astrée-Luce seemed to have grown ten years younger. Apparently I was the first person to whom she had outlined her vision. She was so eager to be at work that she suddenly asked me if I minded packing up again and going back to Tivoli that night. We could the better start work in the morning. What she really wanted was the exhilaration and fatigue of driving (her terrible driving) before she went to bed. So we put back into the car the maid, the Fra Angelico, the ingredients for sauces and the cat, and returned to the Villa Horace at about two in the morning.

The Cardinal was not to know that we were putting up a scaffolding about his good name and freshening the colors; but we were to persuade him not to do some of the things that particularly antagonized the public. The very next morning Astrée-Luce shyly begged me to go and see him. She did not know why, but she had a vague idea that now I knew her hopes my eyes would be open to significant details.

I found him as one could find him every sunny day the year round, seated in the garden, a book on his knee, a reading glass in his left hand, a pen in his right, a head of cabbage and a Belgian hare at his feet. A pile of volumes lay on the table beside him: Appearance and Reality, Spengler, The Golden Bough, Ulysses, Proust, Freud. Already their margins had begun to exhibit the spidery notations in green ink that indicated a closeness of attention that would embarrass all but the greatest authors.

He laid aside his magnifying glass as I came up the path of shells. Eccolo, questo figliolo di Vitman, di Poe, di Vilson, di Guglielmo James,—di Emerson, che dico! What do you want?

Mlle. de Morfontaine wants you to come to dinner Friday night, just the three of us.

Very good. Very nice. What else?

What do you want, Father, for your birthday? Mlle. de Morfontaine wants me to sound you tactfully . . .

Tactfully!—Samuelino, walk to the back of the house and tell my sister you will stay to lunch. I am to have a little Chinese vegetable dish. Will you have that or a little risotto and chestnut-paste? You can buy yourself something solid on the way down hill. How is Astrée-Luce?

Very well.

A little illness would be good for her. I am uncomfortable when I am with her. There are certain doctors, Samuele, who are not happy when they are talking to people in good health. They are so used to the supplicating eyes of patients that say: Shall I live? In the same way I am ill at ease in the company of persons who have never suffered. Astrée-Luce has eyes of blue porcelain. She has a fair pure heart. It is sweet to be in the company of a fair pure heart, but what can one say to it?

There was St. Francis, Father . . .?

But he had been libertine in his youth, or thought he had.—Senta! Who can understand religion unless he has sinned? who can understand literature unless he has suffered? who can understand love unless he has loved without response? Ecc! The first sign of Astrée-Luce’s being in trouble was last month. There is a certain Monsignore who wants her millions for his churches in Bavaria. Every few days he climbs the hill to Tivoli and breathes into her ear: And the rich He hath sent empty away. The poor child trembles and pretty soon Bavaria will have some enormous churches, too ugly for words. Oh, you know, there is for every human being one text in the Bible that can shake him, just as every building has a musical note that can overthrow it. I will not tell you mine, but do you want to know Leda d’Aquilanera’s? She is a great hater, and they say that during the Pater Noster she closes her teeth tight upon: Sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris.

At this he laughed for a long time, his body shaking in silence.

But was not Astrée-Luce devoted to her mother? I asked.

No, she has had no losses. That was when she was ten. She has poetized her, that is all.

Father, why did not that literal faith of hers carry her to a convent?

She promised her dying mother she would stay alive to put a Bourbon on the throne of France.

How can you laugh, Father, at her devotion to . . .

We old men are allowed to laugh at things that you little students may not even smile about. Oh, oh, the house of Bourbon. Would you be surprised if I gave up my life to reviving the royal brother-and-sister marriages of Egypt? Well! It is not more impossible.

Dear Father, won’t you write one more book? Look, you have about you all the greatest books of the first quarter of my century . . .

And very stupid they are, too.

Won’t you make us one. Such a great book, Father Vaini. About yourself, essays like Montaigne,—about China and about your animals and Augustine . . .

Stop! No! Stop at once. You frighten me. Do not you see that the first sign of childhood in me will be the crazy notion that I should write a book? Yes, I could write a book better than this ordure that your age has offered us (and with a sharp blow he pushed over the tower of books; the Belgian hare gave a squeal as he barely escaped being pinned under Schweitzer’s Skizze). But a Montaigne, a Machiavelli . . . a . . . a . . . Swift, I will never be. How horrible, how horrible it would be if you should come here some day and find me writing. God preserve me from the last folly. Oh, Samuele, Samuelino, how bad of you to come here this morning, and awaken all the vulgar prides in an old peasant. No, don’t pick them up. Let the animals soil them. What is the matter with this Twentieth Century of yours . . .? You want me to compliment you because you have broken the atom and bent light? Well, I do, I do.—You may tell our rich friends, tactfully, that I want for my birthday a small Chinese rug now reposing in the window of a shop on the Corso. It would be unbecoming for me to say more than that it is on the left as you approach the Popolo.—The floor of my bedroom is getting colder every morning, and I always promised myself that when I became eighty I might have a rug in my bedroom.

What went wrong?

The first hour was delightful. The Cardinal always ate very little (never meat) and that with preposterous slowness. If his soup took him ten minutes his rice required half an hour. To be sure the elements of trouble were present merely in these friends’ characters. They were so different that just to hear them talking together had an air of high comedy. First, Astrée-Luce made the mistake of referring to the Bavarian Monsignore. She suspected that the Cardinal was out of sympathy with any plans she might have of helping the Church in that direction; she longed to talk over with him the problem of her wealth and its disposition, but he refused to give her the least advice. He had endless resources of ingenuity in evading the subject. As Rome was arranged at that time it was most important that he should exercise no influence on that aspect of his friend’s life. Yet he allowed it to be seen that he knew she would handle the matter foolishly. It ailed him to see such an enormous instrument for progress drift down the wind of ecclesiastical administration.

Now we must remember that it was the eve of his eightieth birthday. We have already seen that the event had precipitated a flood of amused bitterness. As he said later, he should have died at the moment of leaving his work in China. The eight years that had elapsed since then had been a dream of increasing confusion. Living is fighting and away from the field the most frightening changes were taking place in his mind. Faith is fighting, and now that he was no longer fighting he couldn’t find his faith anywhere. This vast reading was doing something to him. . . . But most of all we must remember his terror at the thought that the people of Rome hated him. He would leave in dying a memory without affection and without dignity. An anonymous letter had told him that even in Naples children were kept in good behavior with threats that the Yellow Cardinal would skin them. If one were young one would laugh at such a rumor, but being old one grew cold. He was leaving a world where he was shuddered at for a world that was no longer as distinct as it had been, but which might yet have this consolation that he would not be able to look down from it and see the people surreptitiously spitting on the endings in issimus that would compose his epitaph.

Before I knew it we were in the middle of a wrangle about prayer. Astrée-Luce had always longed to hear the Cardinal discourse upon abstract matters. She had often tried to draw him into arguments on the frequent communion and on the invocation of the saints. He had once whispered to me that she was trying to extract from him the materials for a calendar, such sweet manuals as she could buy in the Place Saint Sulpice. Every word of his was sacred. She would not have hesitated to put him in a Church window with St. Paul. It was only after a few moments that she became aware that he was saying some rather strange things. Could that be Doctrine? If anything he said was difficult all she had to do was to try hard to grasp it. Truth, new truth. So she listened, first with surprise, then with mounting terror.

He was launched upon the paradox that in prayer one should never ask for anything. His dialectic was doing an incredible work. He had decided to be Socratic and was asking Astrée-Luce questions. He wrecked her on several orthodox assumptions. Twice she fell into heresy and was condemned by the councils. She seized hold of St. Paul but the epistle broke in her hand. She came to the surface for the third time but was struck by a Thomist fragment. The previous week the Cardinal had been called to the deathbed of a certain Donna Matilda della Vigna, and it was poor Donna Matilda who was now dragged forth to point the argument. Exactly what had the survivors been praying for? Astrée-Luce was easily routed from the more obvious positions. She became frightened. Presently she rose:

I don’t understand. I don’t understand. You are joking, Father. Aren’t you ashamed of saying such things to bewilder me, when you know how I value everything you say.

Look, then, continued the Cardinal. I shall ask Samuele about this. As he is only a Protestant it will be very easy to entangle him. Samuele, may I assume that God may have intended Donna Matilda to die before long anyway?

Yes, Father, for she died that very night.

But we thought that if we prayed very sincerely we might change His mind.

Why . . . there is authority for our hoping that in extremities our prayer may. . . .

But she died. Then we were not sincere enough! Or persevering enough! Good! Sometimes He grants and sometimes He doesn’t, and Christians are expected to pray hard on the chance that this is one of the times He might relent. What a notion! Astrée-Luce, what a thought!

Father, I can’t stay and hear you talk this way . . .

What a view of these things. Listen. It is incredible that He should change His mind. Because we frightened mortals are on the carpet? Oh! You are a slave to the idea of bargain. The money changers are still in the temple!

Here Astrée-Luce, gone quite white, returned to the arena with one more brave venture: But, Father, you know He answers the requests of a good Catholic. Then she added in a lower voice with tears in her eyes. But you were there, dear Father. If you had deeply wished it you could have altered the . . .

Here he half rose from his chair crying with terrible eyes: Insane child! What are you saying? I? Have I no losses?

Now she flung herself upon the floor before him. You have been saying these things to prove me. What is the answer? I will not let you go until you tell me. Dear Father, you know that prayer is answered. But your clever questions have upset all my old . . . old . . . What is the answer?

Come, sit down, my daughter, and tell me yourself. Think!

This went on for another half-hour. I grew more and more astonished. Mere prayer as a problem was soon left far behind. It was the idea of a benignant power behind the world that was being questioned now. For the Cardinal it was an exercise in rhetoric, sharpened by his temperamental scepticism on the one hand and by his latent resentment against Astrée-Luce on the other. It was a kind of questioning that would have had no effect on sound intellectual believers. It was disastrous for Astrée-Luce because she was a woman without a reason who just this once was trying to reason. She would so have liked to have been a deep thinker, and when she fell it was through her desire to be a different person.

It went on and on. At every fresh proposal he would now cry Bargain! A Bargain! and point out that her prayers sprang from fear or the greed for comfort. Astrée-Luce was going to pieces. I moved over behind her chair and pleaded with the Cardinal by gesture. Was he tormenting her out of caprice? Did he realize her devotion to himself?

At last she seemed to have a light:

My head is in a whirl. But I know now what you mean me to answer. We may not ask for things, or people, or relief from sickness, but we may ask for spiritual qualities; for instance for the advancement of the Church . . .?

Vanity! Vanity! How many years have we been praying for a certain good thing? What have statistics shown us?—I refer to the conversion of France.

With a cry Astrée-Luce rose and left the room. I took upon myself to protest to him.

She is foolish, Samuelino. You cannot call those convictions deep that were overturned with straws. No, trust me. This is for her good. I have been a confessor too long to go astray here. She has the spiritual notions of a school-girl. She must be fed on some harsher bread. Understand that she has never suffered. She is good. She is devout. But as I told you the other day, just by accident she has never known trouble.

Just the same, Eminence, I know her well enough to know that this very moment she is in her chapel, clinging to the altar-rails. She will be depressed for weeks.

But just at that moment Astrée-Luce returned. Her manner was agitated and artificially gracious. Will you excuse me if I go to bed now? she asked. (She never called him Father again.) Please stay and talk with Samuele.

No, no. I must be going. But before I go let me tell you one thing. The real truths are difficult. At first they are forbidding. But they are worth all the others.

I shall be thinking over what we have said.—I . . . I . . . Excuse me, if I ask you something?

Yes, my child, what is it?

Promise me you weren’t joking.

I wasn’t joking at all.

Did I really hear you say that the prayers of good men are of no . . . ? However. Goodnight. You will forgive my slipping away now?

So they took their leaves.

I went to bed worried. I was worrying about Astrée-Luce. Was she going to lose her faith? What do bystanders do in such a case? The loss of one’s faith is always comic to outsiders, especially when the loser is in fine health, wealth, and a fairly sound mind. The loss of any one or all of these has a sort of grandeur; Astrée-Luce should have the loss of her faith depend on one of the others. It’s not a thing one loses in fine weather.

I was wakened from a troubled sleep by a discreet but continuous knocking upon my door. It was Alviero, the majordomo.

Madame says will you please dress and come to her in the library, please.

What’s the matter, Alviero?

I do not know, Signorino. Madame have not sleeped all night. She have been in the church hitting the floor.

All right, Alviero, I’ll be there in a minute. What time is it?

Three o’clock and one-half, Signorino.

I dressed rapidly and hurried to the library. Astrée-Luce was still in her gown. Her face was white and drawn; her hair was disheveled. She came toward me with both hands extended: You will forgive my sending for you, won’t you? I want you to help me. Tell me: were you made unhappy by the strange things Cardinal Vaini said after dinner?

Yes.

Have you Protestants ideas on these things?

Oh, yes, Mlle. de Morfontaine.

Were his ideas new? Is that what everyone is thinking?

No.

Oh, Samuele, what has happened to me! I have sinned. I have sinned the sin of doubt. Shall I ever have peace again? Can the Lord take me back after I have had such thoughts? Of course, of course, I believe that my prayers are answered, but I have lost . . . the . . . the reason why I believe it. Surely, there is a key here. Perhaps it’s just one word. All you have to do is find the one little argument that makes the whole thing natural. Isn’t it strange! I’ve been looking here (and she pointed at the table which was covered with open books, the Bible, Pascal, the Imitation) but I don’t seem to be able to put my finger on the right place. Sit down and try and tell me, my dear friend, what arguments there are that God hears us speak and will answer us.

I talked to her for quite a long while, but achieved nothing. Perhaps I even made it worse. I told her that I was sure that she still believed. I showed her that the very fact that she was distressed about it proved that she was furiously believing. After an hour of this wrestling she seemed a little comforted, however, and picking up a fur coat went back to her cold chapel and prayed diligently for faith until the morning.

At about ten she appeared in the garden and asked me to read a note that she was sending to the Cardinal. I was to pass on it. Dear Cardinal Vaini, I will always honor you above all my friends. I think you love me and wish me well. But in your great learning and multiple interests you have forgotten that we who are not brilliant must cling to our childhood beliefs as best we may. I have been inexpressibly troubled since yesterday evening. I want to ask a favor of you: that you indulge my weakness to the extent of not touching upon matters of belief when I am with you. It gives me great pain to have to ask you this. I beg of you to understand it as apart from any personal feelings of unfriendliness. I hope that I may grow strong enough to talk of these matters with you again.

It was a very bad letter, but that was perhaps due to the content. I suggested shyly that she omit the last sentence. So she copied it and sent it off by a special messenger.

Soon the day came for the end of my stay in the Villa. She came up to my room for a last talk.

Samuele, you have been with me during the saddest days of my life. I cannot deny that all interest has gone out of living for me. I still believe, but I don’t believe as I used to. Perhaps it was not right that I went through life as I did. Now I know that I rose up every morning full of unspeakable happiness. It seldom left me. I had never thought before that my beliefs in themselves were unbelievable. I used to boast that they were, but I did not know what I was saying. Now hours come to me when I hear a voice saying: There is no prayer. There is no God. There are people and trees, millions of them both, every moment dying.—You will come and see me again, won’t you, Samuele? Have I made it very unpleasant for you in the house?

When I reached my rooms in Rome I found three letters from the Cardinal asking me to come and see him at once. As I entered the gate he came toward me eagerly:

How is she? Is she well?

No, Father, she is in great trouble.

Come inside, my son. I must speak to you.

When we entered his study, he closed his door behind him, and said with great emotion: I want to say to you that I have sinned, greatly sinned. I cannot rest until I have tried to repair the harm I have done. Look, look at this letter she has written me.

Yes, I have seen it.

Her letter forbids my explaining what I meant. Is there no way I can reassure her?

There is only one way now. You must regain all her confidence before you touch on such matters again. You must come and go about her house as though nothing had happened—

Oh, but she will never ask me again!

Yes, she is having you all to dinner quite soon, Alix, Donna Leda, and M. Bogard.

Thanks be to God! I thank Thee, I thank Thee, I thank Thee, I thank Thee . . .

May I speak quite boldly, Eminence?

Yes. I am a poor old man, all mistakes. Speak to me as you like.

If you go, take great care not to let slip any remark on religious matters. I beg of you, do not try to reinstate yourself with some orthodox comments. She might misunderstand one little word and think you were attacking her faith again. It is very serious. Your ideas are not orthodox, Father, and if you said an orthodox thing it would not sound sincere and that would be worst of all. But if you come and go simply and affectionately, she will lose her horror of you—

Horror of me!

Yes, and very gradually, perhaps after a year, you may be able—

But I may not live a year!

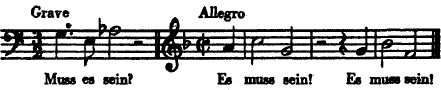

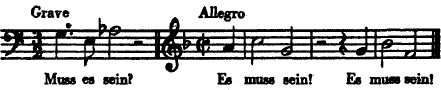

Es muss sein!

This struck him as humorous and ruefully he sang Beethoven’s phrase, adding: All the avenues of life lead to that.

Es muss sein. I should have stayed in China. (Here he fell silent for a while, heaving deep sighs and staring at his yellow hands.) God has chosen to take away my reason. I am an idiot, falling into every ditch. Oh, that I had died long ago—and yet I cannot die until I have righted myself. Hand me that red book behind you. There are two plays about old men, Samuelino, that grow dearer every day to an old man. There is your Lear, and—and opening Oedipus at Colonus he translated slowly:

Generous son of Aegeus, to the gods alone old age and death come never. But all else is confounded by all-mastering time. The strength of earth decays and the strength of the body. Faith dies. Distrust is born. Among friends the same spirit does not last true . . . and bowing his head he let the book fall to the floor. Es muss sein.

I did not go to that dinner. I dined alone with Miss Grier in the city, but at about ten we drove out to Tivoli to sit with the company. As we went I outlined to her discreetly the relations that now existed between two of her best friends: Oh, how stupid he is, she cried. How cruel! What a lot he has forgotten. Don’t you see that the whole thing rests, not on the abstract question as to whether her prayers may be answered, but on the question as to whether ONE prayer may be answered? Her prayer for France . . . Doesn’t he believe such things are real to other people?

He thinks that a little doubt will be good for her. He describes her as the woman who has never suffered.

He is in his dotage. I am so angry I am ill.

At this moment our car drew aside to let pass another hurrying by towards Rome. This was Mlle. de Morfontaine’s great ugly travelling car and the Cardinal was in it.

There he is now, cried Miss Grier. They must have broken up early.

Something’s happened, I said.

Yes, something has very likely happened, God forgive us. If everything were all right, Alix would be driving back with him. Our wonderful company is dissolving. Alix no longer trusts us. Leda is losing her good old commonsense. Astrée-Luce has quarrelled with the Cardinal. I’d better leave Rome and go back to Greenwich.

As we approached the Villa we became aware that something indeed must have happened. The front door was open. The servants were gathered in the hall whispering in front of the closed doors of the drawing rooms. As we entered these opened and Alix, Donna Leda and Mme. Bernstein appeared supporting a sobbing Astrée-Luce. They led her up the stairs to her tower. Miss Grier without questioning the servants as to what had happened, gently urged them to return to their rooms. We passed into the drawing room just in time to see M. Bogard leaving by another door and looking considerably shaken. We sat down in silence, our thoughts full of foreboding. Simultaneously we became aware of a faint odor of powder and smoke and glancing about my eye fell upon a rent near the ceiling beneath which a little pile of white dust had collected on the floor. Mme. Bernstein hurried in and after closing the door carefully behind her, came toward us:

Not a soul must hear of this. Oh, this must be kept so quiet. What a thing to happen! Anything is possible after this. What a blessing that no servants were in the room when . . .

Miss Grier asked her several times what had happened.

I know nothing. I can hardly believe my own senses, she cried. Astrée-Luce must have gone mad. Elizabeth, will you believe me when I tell you that we were sitting here quietly over our coffee—Look, look! I didn’t see that hole in the ceiling before!—Isn’t it all frightful?

Please, Anna, please tell us what happened!

I am.—There we were sitting over our coffee, talking in low voices of this and that, when suddenly Astrée-Luce went over to the piano, picked up a revolver from among the flowers and shot at the good Cardinal.

Anna! is he hurt?

No. It didn’t even come near him. But what a thing to happen! What on earth could have made her do such a thing! We were friends—we were all such good friends. I do not understand anything.

Try and think, Anna: did she say anything when she fired at him, or before she fired?

That’s the strangest of all. You won’t believe me. She called out: The Devil is here. The Devil has come into this room. At the Cardinal!

What had he been saying?

Nothing! Merely everyday things. We had been telling stories about the peasants. He had been telling us about some peasants he had come across on his walks outside S. Pancrazio.

Suddenly Alix appeared: Elizabeth, go to her quickly. She wants to see you. She is alone.

Miss Grier hurried out.

Alix turned to me:

Samuele, you know the majordomo better than we do. Will you go and tell him that Astrée-Luce has had a nervous breakdown. That she thought she saw a burglar at the window, and that she fired at him. It is so important for the dear Father’s sake that no hint of this gets about.

I went out and found Alviero. He knew the explanation was insufficient, but utterly devoted to the whole Cabala he could be trusted to dress the story at exactly the points that would most convince the other servants.

Alix did not understand what lay back of the shot, but she was able to recall the conversation that had led up to it. The Cardinal had told the following simple story, an incident he had witnessed in one of his walks outside the city wall:

A farmer wished to break his six-year-old daughter of crying. One afternoon he led her by the hand to the center of a marshy waste, thickly grown with wiry reeds well above the child’s head. There he had suddenly flung away her hand, saying: Now are you going to cry any more? The child, with a last rush of contrary pride and with a beginning of fear, started to cry. All right, shouted the father, we don’t want any bad children in our house. I’m going to leave you here with the tigers. Goodbye. And jumping out of the child’s sight, repaired to a wine shop at the edge of the waste and sat down for an hour’s cardplaying. The child strayed about from hummock to hummock, wailing. In due time the father reappeared and taking her affectionately by the hand led her home.

That was all.

But Astrée-Luce had never learned, as the rest of us have, to harden her heart slightly before stories of cruelty or injustice. She may have had no losses of her own, but she had always been ready to expose her imagination to the full force of other people’s wrongs. Such an anecdote would have drawn from others a sigh, a swift protective contraction of the lips and a smile of gratitude for its safe conclusion. But to Astrée-Luce it was the vividest reminder that the God whose business it was to brood over the world ministering to the discouraged and the mistreated, was no more. The Cardinal had killed him. There was no one left to soothe the horse that has been beaten to death. The kittens that the boys fling against the wall have no one to speak for them. The dog in torment that keeps his eyes upon her face, and licks her hands even while his eyes grow dim, shall have no comforter but her. This was not a casual story the Cardinal was telling: it concealed a covert allusion to their conversation of the preceding week. It was a taunt. It was a sort of curse. Look at the world without God, he was saying. Get used to it. If she had lost God, oh how clearly she had gained the Devil. Here he was triumphing in this lacerating story. Astrée-Luce went over to the piano, picked up a revolver from the flowers and shot at the Cardinal, crying: The Devil has come into this room!

As the Cardinal drove back that night he kept repeating to himself the words: Then these things are real! It had required Astrée-Luce’s shot to show him that belief had long since become for him a delectable game. One piled syllogism on syllogism, but the foundations were diaphanous. He strained to remember what faith was like when he had had it. He kept dragging before his mind’s eye the young priest in China exhorting the families of the Mandarins. That was himself. Oh, to retrace the way. He would go back to China. If he could look again on the faces that were serene with a serenity he had given them, perhaps he could steal it back. But side by side with this hope was a terrible knowledge: no words could describe the conviction with which he saw himself guilty of the greatest of all sins. Murder was child’s play compared to what he had done.

The firing of the shot had done as much for Astrée-Luce. On awaking, her terror lest she had harmed him, later her fear that she had fallen out of reach of his forgiveness was greater than had been her misery in a world without faith. It was given to me to carry from each to the other the first messages of anxious affection. When Astrée-Luce and the Cardinal discovered that they were living in a world where such things could be forgiven, that no actions were too complicated but that love could understand, or dismiss them, on that day they began their lives all over again. This reconciliation was never put into words, in fact it remained to the end merely in a state of hope. They longed to see one another again, but it would have been impossible. They dreamed of one of those long conversations that one never has on earth, but which one projects so easily at midnight, alone and wise; words are not rich enough nor kisses sufficiently compelling to repair all our havoc.

He received permission to return to China, and sailed within a few weeks. Several days after leaving Aden he fell ill of a fever and knew that he was to die. He called the Captain and the ship’s doctor to him and told them that if they buried him at sea they would have to face the indignation of the Church, but that they would be fulfilling his dearest wish. He took what measures he could to shift upon himself the blame for such an irregularity. Better, better to be tossing in the tides of the Bengal Sea and to be nosed by a passing shark, than to lie, a sinner of sinners, under a marble tomb with the inevitable insignis pietate, the inescapable ornatissimus.