CHAPTER 7

Quality Controls Quantity

Metal Controls Wood

If the ideas in Chinese medicine begin to seem abstract, remember: they come from nature. Chinese medicine has many terms and ideas to grasp, but the point of reference is always the same natural world that surrounds all of us. For example, to understand the term heat, simply think about standing outside on a hot summer day at noon without any shade. To understand the term dryness, think about the soil in your garden that has been exposed to months of hot sun without any rain. To understand the term internal wind, think about what it would be like to be outside in a storm, and then imagine that happening inside you.

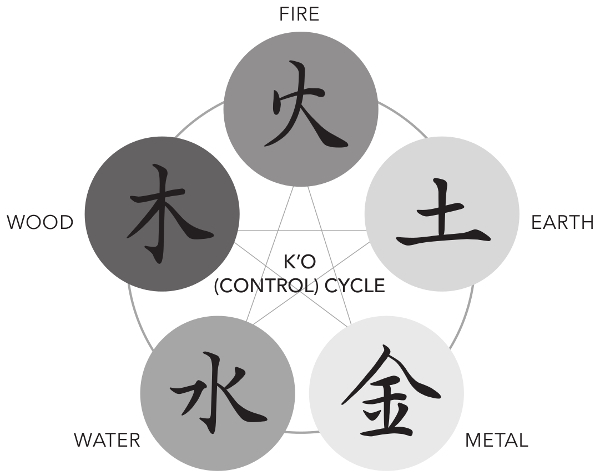

To understand how the Water phase nourishes the Wood, consider how your houseplants or a farmer’s tomatoes need moisture to grow. While this nourishing part of nature is represented by a Sheng cycle line on the outside of the Five Phases circle, the K’o cycle—or the control cycle—is represented on the inside of the circle. While the Sheng cycle describes how different aspects of nature and different parts of our lives feed each other, the K’o cycle indicates how they create limits to maintain balance.1

In terms of Yin and Yang, the outside line is about feeding and increasing—which is Yang—and the inside line limits and decreases—which is Yin.2 Not surprisingly, in the view of Chinese medicine we need to support both the growth and the limiting of each aspect of ourselves and the world. Not only is this essential to our personal well-being, but it is also a vital part of the effective remedy for climate change.

The severe storms that are becoming commonplace are the result of a global excess of the Wood, which mirrors the Wood excess within us. As we discussed in chapter 6, part of what contributes to the dynamic of increased wind is the planet’s coolant of Water being compromised. In particular, not only are we creating greenhouse gases that warm the climate, we’re also losing the coolant of the planet as we burn the planet’s jing as oil. Just as maintaining the balance of Water individually and globally is of utmost importance, it’s also essential to recognize the importance of the Metal.

As with the other phases, the Metal has many associations: the Lung and Large Intestine, autumn, dry climates, grief, weeping, old age, tools such as knives and saws, and precious metals like gold and silver. Looking at the Five Phases circle, the Metal is located at the bottom, indicating its descending Yin nature. On a deeper level, the Metal is also associated with precision and our connection to the divine.3 While it is associated with spirituality and religion, this experience of something greater than our physical selves isn’t exclusive to a particular organization or practice. As we’ll talk about later in this chapter, not only is this experience of the divine an essential part of our health, it’s also essential medicine to treat some of root causes of our warming planet.

To understand the Metal, think about autumn. Here in northern New England, it’s the season that follows the harvest, when the abundance of corn, squash, and melons subsides and is replaced with quiet and stillness. The tops of most plants die, and the greens of summer give way to browns and grays that fill our gardens and fields. With autumn comes a decline in energy, and the sunny warmth of summer slowly shifts to a cold darkness.

If you’ve ever walked through the woods in October and November, you’ve experienced the Metal. The trees’ leaves are dying, and they fall and blanket the forest floor. Though spring and summer are marked by lively sounds, in the fall there is quiet. Walking through a forest of maple and oak, you can only hear the crunch of dry leaves underfoot. Little else in the forest moves around or makes much sound, as animals are getting ready to hibernate or move south. The quiet and stillness of the woods in fall is the embodiment of Metal.

Associations of Metal

Within us, the Lung and Large Intestine are part of the Metal. Similar to the Western view, in Chinese medicine the Lung takes in oxygen and the Large Intestine gets rid of waste. Within a more holistic perspective, however, these organs are more than just their physical functions. The Lung also takes in what Chinese medicine calls the Qi from heaven. Referred to as Heavenly Qi or Ancestral Qi, the Lungs take in this refined energy from the air with each breath we take.4 Heavenly Qi provides us with inspiration and a direct connection to the sacred. From this viewpoint, heaven is not some far off place that we might get to when we die—instead, we access heaven with every breath.

Divinity is not reserved for particular religious buildings or structures. And it’s not exclusive to a particular spiritual sect or creed. It reaches everyone, regardless of their position in society. Equally important, it’s not at all confined to humans or even to what we might call sentient life.

This experience of divinity, so essential to our health, fills everyone and everything; there is no hierarchy of sacredness in nature. Just as it’s not reserved for people who have a certain amount of money and who look a certain way, it’s also not reserved for us humans. All life is sacred—the plants, trees, animals, and insects, they’re all sacred. Even things that from our usual Western view aren’t alive are sacred. The rocks, the wind, the air, the sunshine, the soil—they’re all sacred as well.

Looking back to the physical associations of the Metal, in addition to extracting the last small amount of nourishment from the food we eat and then eradicating physical waste, the Large Intestine also clears out things we don’t need mentally or emotionally.5 Similarly, the Lung takes in the purity of oxygen and Heavenly Qi with each inhale and release impurities with each exhale.6

If we look outside our bodies and within nature, we see that the tops of plants in our gardens die off and trees lose their leaves each fall as they are letting go of what’s nonessential in order to survive. To make it through the cold and dark of winter, plants concentrate their Qi and their nutrients inward and underground. When it is below freezing for months at a time, trees and plants need to expend only what’s necessary; letting go of what’s not essential enables this to happen.

In addition to shedding the unnecessary, Metal is also related to precision—think of it as a sharp knife’s ability to cut through things cleanly. Here in the northeast, it’s important to prune apple trees regularly to concentrate their energy on making fruit rather than making more branches. A sharp saw enables us to make these cuts effectively and efficiently. In order to cut out the excess, the precision and sharpness of Metal is necessary.

Not only must Metal be able to cut precisely, it also is the ability to measure precisely. Being able to measure or quantify something helps us to better understand its value. According to Chinese medicine teacher Thea Elijah, this precision of the Metal is connected to the historical tradition in China of verifying the measurements and weights of scales each year in the fall.7

The descending energy of the Metal is also related to the loss of something that was dear to us. It could be something as concrete as a family member or something as open-ended as a stage in one’s life. When we have to let go of anything that had real value to us, we are experiencing the energy of the Metal. The emotion associated with autumn is grief, which is one expression of this deep sense of loss, and the sound of the Metal is weeping—another outward expression of letting go.

When we are able to experience grief fully, it opens us up. In particular, it opens the Lungs and can sharpen our understanding of what is truly important in life. In the context of the Metal, this experience is closely connected to the bigger and deeper parts of our lives: spirituality, religion, and questions about who we are and why we’re here.

Old age is associated with the Metal as it is the stage of life when, hopefully, we can reflect back on how we’ve lived and the truths we’ve learned. Rather than being thought of as a time of failing health and a loss of vitality—as is a common way to think about it in our country—old age is a time when we can contemplate what our lives mean.

Experiencing Metal

To better understand Metal, try the following exercise of sitting quietly with your eyes closed. In a quiet place, make yourself comfortable sitting on the ground with your legs crossed, or sit in a chair with both feet on the floor. Relax your body as much as possible and breathe slow, deep breaths. Lightly place the tip of your tongue on the top, front, center of your mouth, where the roof of your mouth and back of your teeth meet. If possible, breathe through your nose, inhaling and exhaling in a relaxed rhythm. As is done during Tai Chi practice, try to imagine that when you’re inhaling you’re drawing out a spool of silk, which needs to be done carefully and consistently so as not to break or clump the thread.8 Follow your breath. Pay attention to its rhythm, note where it’s not relaxed or deep, and see if you can gently return it to a steady, smooth pace.

After a few minutes of focusing on your breathing, try to relax your mind. Take note of what ideas or images are appearing, and see if you can let them go. Using your inhale and exhale as encouragement, begin to clear your thoughts. Let yourself stop thinking about your job, or things you have to do, or bills you need to pay. Try not to worry about the next paper you have to write or the fight you just had with a friend. Try not to worry about climate change.

After a few more minutes, open your eyes. Even after a brief period of following our breath and relaxing our mind, many of us will feel more peaceful. Our heart rate has probably slowed and we may feel less stressed than when we started.

The internal relaxation that comes from sitting quietly is part of the Metal. Just as walking through the woods in the fall can help us comprehend how Chinese medicine understands this season, quieting our mind and relaxing our breath can also allow us to experience this phase. The Metal is introspective and peaceful: it’s the sense of inspiration that comes with each conscious inhale and exhale of Heavenly Qi.

If you tried to sit still and quiet your mind and had a hard time, you’re not alone. Our mental overactivity is at epidemic levels in our overstimulated, planet-warming culture. Similar to how the planet is warming quickly, our minds are overheated. A common result of too much mental and visual stimulation—from computers, cell phones, or TVs, for example—is that our organs heat up internally. This can eventually overstimulate our thoughts, making it difficult to experience peace. Taking away some of the outside distraction, even for a short time, can make it clear—sometimes uncomfortably so—just how constantly busy things are within us.

Even if it’s uncomfortable in the beginning, it’s vital that we work on cooling ourselves down internally. We can do this by sitting quietly and following our breath or by engaging in more formal sitting meditation. We can also study and practice forms of moving mediation as well. Qi Gong often involves keeping our feet in one spot as we slowly and rhythmically move our bodies and focus on our breath to circulate and concentrate our energy. Tai Chi also helps quiet the mind and focus the energy as we work through a form of movement. In addition to concentrating our Qi and relaxing our thoughts, Tai Chi is also a form of martial arts.

We can also achieve this just by being in a quiet, natural place—like in the woods or near the ocean—and allowing ourselves to relax. Especially for those of us already committed to addressing climate change, experiencing internal peace—where our mind is quiet when we take away the distraction of our busy world—is part of the long-term remedy for our warming planet. It’s unlikely that we can help create a more sustainable culture that doesn’t continue to overheat the planet if we ourselves are overstimulated.

Meaning Controls Growth: Metal Controls Wood

Given our cultural excess of Wood, in the form of new things and expansion, more Metal is something we greatly need. If something is overgrowing, it’s important to not keep feeding it. If you’re trying to get rid of the crab grass in your garden, for example, it doesn’t make much sense to fertilize it. For us collectively, it also doesn’t make sense to keep feeding our belief in continuous growth if we want to address the underlying issues of climate change. What does make sense is to increase the Metal, within us and within our country.

As the line between them indicates, there’s a direct connection between Wood (spring) and Metal (autumn). This is not a supportive relationship, however, but rather a relationship of control. If you want a plant to grow, you can ensure this by adding water. If you want to limit and control growth, you must cut it down.

In chapter 6, we talked about how long-term excessive growth in the Wood has been fueled by the Water. In our own selves, this means we’re regularly pulling from our deep reserves of jing when we use stimulants to keep going. In our economy, we’re drilling and burning oil to maintain an economic system based on a belief in continuous growth. In addition to constantly pulling from the Water, having Wood expand continuously also means that we have weakened the influence of the Metal.

An oak tree doesn’t grow to be a thousand feet tall and a tomato plant doesn’t take over a two-acre field because there are natural limits. When we chose to create systems based on a belief in continuous growth, we had to limit the Metal’s control of the Wood. In the context of our economic system, we’re hoping that it will be a sunny, warm spring day every single day. When we’re only interested in the spring of Wood and the Yang of warmth and sunshine, we avoid the autumn of Metal and the Yin of cold and dark. Yet, despite our avoidance, just as day becomes night and light becomes dark, spring and summer will always eventually become fall.

Taking into account what we associate with the Metal, if we try to have something grow forever, we’re also limiting the natural quieting effects of the spiritual and the religious. Thus, part of the inevitable result of our overemphasis on the growth of the Wood is the loss of the sacred.

Over time, internal practices like sitting quietly and being in nature can help us experience Metal in our everyday lives. Simple things like eating a meal, looking at a sunset, or being someone you love can be of real, deep importance. Deriving such meaning from basic experiences comes from the Metal—it comes from the sacredness in the food we eat, the cycles of nature, and the people we are with.

To be clear, it’s not something outside us that enables us to experience the world this way—it’s within us, with each breath we take. In Chinese medicine, a connection to the sacred here on earth, and a sense of the divine in everyday life, happens with each inhale. When we’re aiming for continuous growth and have whole cultural systems based on it, we’re weakening this sense of deeper meaning.

What allows us to erroneously believe that the economy can grow continuously is the dampening of the sacred and the weakening of the limiting effects of the Metal. It would be much harder to continuously and recklessly drill and dig for oil, for example, if we recognized that the ground itself and what’s found in it have the same universal Qi that we do. It would also be difficult to continue to cut down forests on a massive scale if we appreciated that the trees are as alive and as conscious as you and I. Continuing to live in a way that destabilizes the climate would seem senseless if we recognized that rather than being connected to the planet, we are the planet itself.

In our era of climate change, spirituality and internal practices are essential aspects of the overall remedy, given their limiting effects on continuous growth. In addition to our own direct experiences with the sacred, listening to ecologically aware spiritual teachers and religious leaders address our overemphasis on the Wood and undervaluing of the Metal is of utmost importance.

In order for something to grow continuously—like the economy, for example—whatever could help control that expansion has to be discarded. The natural limits to growth that we see in the relationship between the Metal and the Wood has to be severed. If we hope that our economic system will grow forever—becoming the monetary equivalent of a thousand-foot-tall oak tree—we have to devalue the relationship between the Metal and the Wood.

An embodied sense of the preciousness of all life and all things in nature is a potent antidote to the quest for never-ending economic expansion. We’ve had to, necessarily, try to get rid of this sense of the sacred in the quest to ensure ongoing, unchecked economic growth. We can’t have the cultural equivalent of a well-sharpened saw cutting away all the things we don’t need from our economic system if we hope to have it grow continuously.

In order for the economy to grow forever, the land can’t be sacred, the air can’t be our connection to heaven, and oil can’t be the accumulated wisdom of the planet. For the Wood to continue to expand unchecked in the form of continuous economic growth, trees become resources, people become interchangeable cogs in the industrial system, and food is just another commodity to be bought and sold. When we recognize that trees have the same Qi as you and I, that each of us have a unique contribution to offer the world, and that food is our connection to the Earth, natural and necessary limits are placed on economic growth.

If this loss of meaning and an absence of the sacred seems like a sad state of affairs, it is. We’ve been persuaded to pursue the next new gadget rather than find real value or meaning in our lives. But ultimately, that new car or phone cannot provide us with any lasting sense of meaning. Not only have we consciously and unconsciously agreed to this deal—of looking for purpose in the pursuit of new and often unneeded things—we call it progress. However, instead of being an indication of advancement, in actuality it’s a clear symptom of our sickness.

A new phone, a new car, or a new computer are a hollow replacement for a sense of meaning and a direct experience of the divine. The newness of the world when you open your eyes after meditating, the experience of being filled with vitality after Qi Gong, and the feeling of interconnection from a walk in the woods gives us so much more than the pursuit of the next new thing. A vital part of the antidote to continuous growth is a deep sense of meaning and a direct connection to something bigger than our individual lives.

As we talked about earlier when discussing Yin and Yang, there are advertisers, companies, and stores that are happy to sell us a reprieve from our own internal condition. But just as the discomfort from a lack of Yin isn’t treated by buying things, neither is our need for meaning. While new gadgets can distract us for a little while, once that wears off, the basic question remain: What gives our life real meaning?

Meaning Nourishes Wisdom: Metal Nourishes Water

As the Five Phases cycle shows us, in addition to controlling Wood, Metal also supports and helps maintain the well-being of Water.9 As we discussed earlier, one example of our collective lack of wisdom is continuing to burn oil even though the consequences are clear. One part of treating this is to address the assumptions that foster our belief in continuous growth. Another essential remedy, however, is to understand that a healthy Metal feeds and nourishes Water, both within us and within the planet.

To understand the Sheng cycle relationship between these two phases, think about Water coming out of the ground. Here in Vermont, where many of us rely on private wells, water often contains minerals, as it’s filtered down through stone before it’s pumped back to the surface. The nutrients it accumulates create what’s called hard water, which is nutritious and often cloudy in appearance.

From the view of Chinese medicine, the minerals in well water and the nutrition they provide are part of the Sheng cycle. The hardness of water comes from the minerals that are dissolved, making it more nutritious. In our era of climate change, we need a similar remedy for our own lives and for our country. To help create balance, we need a deep sense of meaning and a direct experience of the sacred that is the Metal to feed the wisdom of the Water to address climate change.

Just as the excess of Wood in our country is depleting Water directly, our belief in continuous growth is also weakening Metal—which depletes Water as well. This is because when we lose a sense of real meaning and a connection to the divine, we also lose what it is that feeds wisdom. A long-term, multigenerational understanding of personal health and ecological sustainability that derives from Water is fed by sitting quietly, moving slowing, and being in nature—all part of the Metal. It’s not a coincidence that for millennia Chinese medicine has emphasized practices like meditation, Tai Chi, Qi Gong, and regularly spending time in nature.10 We need internal quiet, relaxed breathing, and a sense of connection—from internal practices and spending time in nature—so that we can strengthen the Metal, which in turn feeds the Water.

Case Study of Metal Controlling Wood

In our clinic, we regularly witness the Metal’s ability to control Wood when treating patients. Mary, a patient in her early thirties who came for help with debilitating migraines, stands out in particular. Mary was fit from exercising regularly, and when she smiled she seemed relaxed. Yet when I asked her about her symptoms, she also had a somewhat faraway look in her eyes—common in someone who experiences severe pain regularly. She also looked tired and pale.

Two or three times a week, Mary would get severe pounding headaches in her temples and at the top of her head. The pain was often accompanied by nausea. The migraines would come on quickly, sometimes taking her by surprise. She could go from feeling fine one moment to needing to lie down in a silent, dark room the next. Mary also had a limited appetite and not much interest in food, even when she didn’t have a headache.

Mary’s pulse and tongue told a story similar to Tom’s in chapter 6. The pulses that correspond to the Wood Element were pounding, and were close to the surface, indicating a severe excess in the Liver and Gallbladder of heat and internal wind. As is commonly the case, Mary’s dramatic excess of Wood had caused a significant deficiency in Water. Her pulses that correspond to the Kidney and the Bladder indicated that they were dry and Yin deficient as well as weak and Yang deficient.

Not only was Mary experiencing severe weakness in the Water, she also had a significant weakness in the Metal. Underneath my index finger on her right wrist, there was very little Qi in the pulses of the Large Intestine and Lung. The Qi that was there was much deeper than that of the Wood, indicating that the Lung and Large Intestine were worn out. That both Metal organs were weak was part of the dynamic that had allowed the Wood to become so excessive. As the heat and wind of the Liver and Gallbladder pushed things upward, there was connected tiredness of the descending Qi of the Lung and Large Intestine.

Mary’s tongue told a similar story as her pulse. Her whole tongue was very red, indicating excessive heat, and there was a deep crack from the back to the front, indicating significant dryness. As with Tom, what was also prominent was the way her tongue dramatically bent to the side, indicating a great deal of internal wind. At the front of her tongue, Mary also had a wide and deep indent in the position associated with the Lung. As part of the job of Qi is to hold things up, the dip indicated a weakness of the Lung, in particular.

Together, the pulse and tongue diagnoses showed a clear pattern: Mary’s symptoms were the result of her Water’s inability to cool things down, as well as her weak Metal’s inability to control the excess of Wood.

To treat Mary, acupuncture and herbs were used to clear out heat and wind in the Liver and Gallbladder, increasing the coolant and strength of the Kidney and Bladder, and strengthening the Qi of the Metal. To help the Wood relax and to strengthen the Water and Metal, I also suggested that Mary take it easy and not exercise at all until her migraines were better. I encouraged her to rest as much as possible.

After a few weeks of acupuncture, herbs, no exercise, and more sleep, Mary’s pain had decreased significantly. When she did have a headache, it was mild and without the dizziness or nausea, and didn’t make her lie down in a dark room. After about two months, Mary’s symptoms were gone completely, and her energy and appetite also returned. She also had more color in her face, her eyes were clearer, and she looked and felt much better overall.

Quality Controls Quantity

Just as it helped to control Mary’s migraines, Metal’s ability to balance Wood can also help us on a bigger scale in our country. Because the remedy to our overemphasis on newness and doing is the old and nondoing, we need to increase the calm energy of autumn to check the excess of spring within ourselves and our culture. To help balance the overemphasis on buying more things, we need to appreciate the things we already have. And rather than attempting to create meaning through the pursuit of the next new gadget, we can recognize in nature the sacredness of all life and all things.

Even though we already have so much material stuff in our country, we are constantly encouraged to want more. Not only do many of us have more than we need, much of what we have is designed to be used briefly and then discarded for the next new thing. Because we have more than we need, we value the things we do have less and less.

We can think about this in terms of gardening, too—if you only have one shovel that you use to pull weeds and plant seedlings, it’s likely you’ll treat it well. If you use it year after year, you’re more likely to make sure it’s sharp to make digging easier. It’s also likely that you’ll make sure the handle remains smooth and the wood oiled, so it’s less likely to crack or break.

But if, instead of having one shovel, you have fifty, the condition of the one shovel you’re currently using probably doesn’t matter much to you. Its sharpness or the condition of the handle are less important if you know that if this one breaks, you can just get rid of it. In other words, when you have more shovels than you need, the value of each individual shovel decreases. This relationship between an increase in the number of things we have and the decrease in their value is the connection between the Wood and Metal. The more things we have, the less we value them; this is true for shovels, gadgets, clothes, and nearly everything else.

To help balance our overinfatuation with getting new things, the first step is to truly value the things that we already have. This could be a shovel for gardening, a well-maintained bike to get around town, or the laptop I’m using to write this book. When we appreciate the things we have, we need fewer things.

Of course, one reason we continue to buy stuff at a rate that destabilizes the climate is that many products are designed to break or become obsolete soon after they’re purchased. Planned obsolescence might increase sales for certain companies, but it’s clearly not sustainable ecologically.

If you do need to buy something, try to get the best and most ecological version you can afford. Don’t pay for unnecessary frills or something you don’t need; invest in quality. For example, you might spend twice as much on a shovel made of hardwood and galvanized metal, but it could last for decades of regular use. With food, buying at a farmers market or directly from a local farm will likely cost more than getting the cheapest meal at a supermarket chain. But the freshness, taste, and nutrition from eating local are part of what you’re paying for.

We need to be able to determine the quality of something, which is what the Lung allows us to do. Physically, when we breathe, the Lung knows what to take in—the purity of oxygen—and what to discard—the impurities we exhale. When it comes to objects in our lives, the Lung also helps us recognize what’s essential and encourages us to get rid of what’s not. Similarly, the Large Intestine helps us extract value out of all aspects of our lives and let go of things we don’t need.

If we constantly buy things without much value that aren’t made to last, we’re overtaxing the Metal. Physiologically, the Lung and Large Intestine must continuously discard the impurities and toxins in what we eat, drink, and breathe, including pesticides, herbicides, preservatives, and a myriad of other chemicals. Outside the body, we’re also bombarding ourselves with purchases of meaningless, disposable things we don’t need. This not only weakens the Qi of both organs, but also affects our ability to discern what’s really important and valuable. In turn, Metal’s ability to control the excess of Wood is further compromised.

If we were to change our larger economic system to one not based on the Wood of continuously buying new things, we could increase Metal’s influence and place value on repairing and reusing the things we already have. Doing so would also increase the worth of old and traditional tools and technologies rather than unquestioningly having faith in whatever modern convenience is being marketed to us next.

More Metal in the economy would also emphasize and pay for maintenance and restoration—of the land, the water, and the air—rather than destruction. More Metal in our health care system would mean valuing and paying for the promotion of health rather than waiting for sickness. Rather than buying an inexpensive over-the-counter remedy over and over to try to make symptoms go away, you can go to an acupuncturist or Chinese herbalist to address where your symptoms are actually coming from.

To find balance within ourselves and within our culture, it’s imperative that we understand that the assumption of excess and more must be balanced with the discernment of reducing and less. It’s also imperative that the focus on quantity be tempered with the value of quality. It’s also of vital importance that the growth and expansion of Wood be balanced with the discernment and letting-go of Metal.

As we’ll talk about next, with the condition of the Wood and Water within ourselves and our culture, other part of our lives will inevitably be affected. Our overemphasis on growth and expansion and our lack of wisdom is affecting the way we communicate—the condition of our Wood and Water is impacting the state of our Fire.