At a time when Australia was struggling to find a national architectural style, along came this brash young man with American training and a European sensibility, who built a relentlessly modern house in the International Style in the heart of suburban bushland.

The exterior mural was designed and painted by Seidler himself. The colours are repeated in the interior to link the two spaces, such as the yellow in the door, above.

Set amongst the bushland of a conservative northern Sydney suburb is the house architect Harry Seidler designed for his parents.

The house that Harry Seidler designed and built for his parents in Wahroonga, on Sydney’s North Shore, was completed in 1950. It launched his career, defined the decade and caused a stir. Not only did it excite the architectural establishment, but it also attracted public interest in a way that domestic architecture rarely did. Visiting the perfectly preserved house more than 50 years later, it still feels daringly modern, so it’s easy to imagine the curious public who came all those years ago to gawp at the house that Harry built.

Harry Seidler was born in 1923 in Vienna, where he lived with his well-to-do parents, Max and Rose, in an apartment remodelled by avant-garde architect Fritz Reichl. With the Nazi occupation of Austria in 1938, Seidler followed his brother Marcell to England, and was taken as a refugee to live with two ladies in Cambridge, where he attended school for 18 months. He was then interned, in Liverpool and the Isle of Man, before being transported to Canada. After his release in 1941, he gained a first class honours degree from the University of Manitoba before winning a scholarship to Harvard Graduate Design School.

The period at Harvard was to be a defining experience for him. Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus movement, and Marcel Breuer, a teacher and practitioner of the Bauhaus principles of design, ran the postgraduate course. Later, Seidler worked as Breuer’s chief assistant in his architectural practice in New York, studied design with Josef Albers (a former Bauhaus teacher) in the short-lived, but highly influential Black Mountain College, North Carolina, and spent a summer with flamboyant modernist Oscar Niemeyer in Brazil. All combined to ensure that, by the time Seidler moved to Australia at the behest of his parents, he had experienced an amazing exposure to the world’s most influential architects and teachers. At 25, his architectural mindset was confident, complete and ready to be exercised.

‘Rose Seidler House may look like a young architect’s house for his parents, but really it is built manifesto, representing all the Modernist principles of Australia’s most famous modern architect…As an attention getter the house remains unbeaten. A homage to Seidler’s former New York employer Marcel Breuer, this house – with its TV-screen frontality, open pinwheel plan and elevated trapdoor entry – perches on the grassy site like an arrival from space.’ This remarkably astute quote from Elizabeth Farrelly’s article in The Sydney Morning Herald in 2005 sums up the house as a statement of intent.

At a time when Australia was struggling to find a national architectural style, along came this brash young man with American training and a European sensibility, who built a relentlessly modern house in the International Style in the heart of suburban bushland. While the design came about with apparent ease, the construction was fraught with difficulty. There were problems finding a builder to undertake such a project, but with the help of well-established architect Sydney Ancher, Seidler appointed Bret Lake. In the postwar period, materials were not easy to come by and there are stories of Seidler driving around building sites, picking up a few bricks here, a few bricks there.

Even the siting of the house was considered unusual. In an era where the front door inevitably faced the street, the Rose Seidler House is positioned in the centre of the block, with trees providing privacy and floor-to-ceiling windows opening up the house to bushland views.

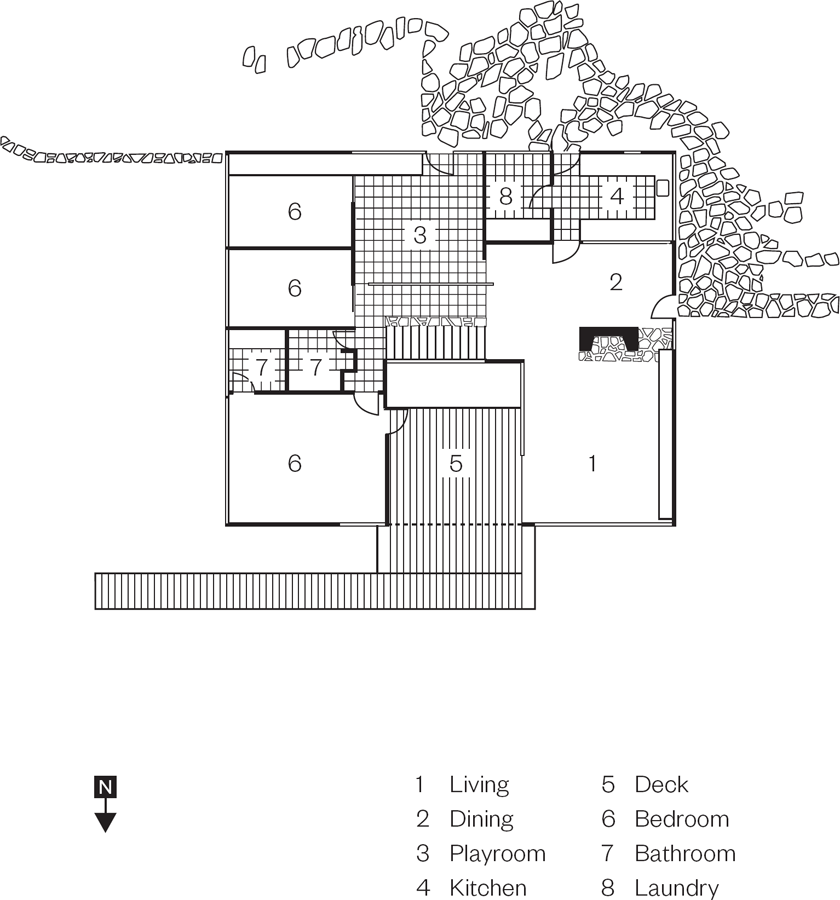

Such was the influence of Breuer that the house conforms to his binuclear layout, with one arm containing the public areas – the living room, dining room and the kitchen – and the other, the private ones – the bedrooms and bathrooms. Connecting the two internally is the playroom and, externally, a courtyard. Because there are few internal walls, and glass replaces external ones, there is a tremendous sense of openness. For flexibility, a dividing curtain ‘wall’ can be pulled across to segregate the living area from the playroom. Today, we are accustomed to this flow of one living space to another, but in the Fifties it must have seemed highly unconventional. A design factor the newspapers of the day picked up on was its elevation. Traditionally, houses were solid and grounded while this seems to float, supported by spindly legs and sporting a strange projection to one side – a ramp.

This house has endured stylistically because of the conviction with which it was planned both inside and out. Take the colour scheme. ‘People who live complicated lives (and most of us seem to) cannot be comfortable in a highly colourful interior,’ said Seidler in 1954. Here, bold colour, neutrals and earthy shades are held in perfect balance, with the external mural setting the tone. Painted by Seidler himself, it recalls artists Miró and Calder, whom Seidler later collected, and captures all the colours used in the interior. There are cool greys on the walls, mid-greys in the carpet and deep brown upholstery on the sofa. The curtains, which provide walls of colour when drawn, are bright orange, electric blue and dark brown.

The furniture was bought, along with the light fittings, in New York before he left, knowing that he wouldn’t get what he wanted in Sydney. DCM dining chairs, designed in 1946 by Charles and Ray Eames, were the result of wartime exploration into the potential of moulded ply. Combined with a chromed steel structure and exposed rubber shock-mounts, the look is industrial rather than domestic. The Eero Saarinen Womb chair (1948) and Grasshopper chair (1947) have a sculptural quality that provides a counterpoint to the linear design of the living room. The Ferrari-Hardoy Butterfly chair in eye-popping yellow is placed beside the mural where it looks like a 3D extension of the work’s black outline and infill of solid primary colour. The built-in furniture was designed by Seidler, and made by another Viennese immigrant, craftsman Paul Kafka. The cantilevered wall cabinet is a particularly contemporary execution, with its combination of black polished glass and matt painted wood suspended on an Atlantic grey painted wall.

The fireplace and balustrade in rough-hewn sandstone are the only points in the interior where a sense of the randomness of nature intrudes, reflecting the exterior walls and the organic environment within which the house sits.

With the scarcity of materials in this period, necessity proved the mother of invention. Seidler used galvanised piping for the handrail, and explored the possibilities of other new materials.

The asphalt tiles in the playroom, while deemed less successful because of their lack of durability, have achieved a rich patina over time. Seidler’s experimental thinking was particularly successful in the kitchen. It was the last word in kitchen design in its day, with House & Garden and Home Beautiful magazines wowing their readers with the cutting-edge, labour-saving devices, wipe-clean industrial stainless steel benchtops and coloured glass-fronted cabinetry. Not even the convention of handles was observed – simple, circular cut-out shapes in the glass were enough. A Dishlex dishwasher, Crosley Shelvador fridge of grand American proportions, Kenwood Chef Mixmaster and Bendix front-loading washing machine ensured this ‘machine for living’ had all the necessary cogs in place.

While the bedrooms are small, they are well-equipped and reflect more intensely the colour scheme of the rest of the house. By extending the door cavities to ceiling height, and using sliding doors, the entrance to the rooms feels generous, and the outlook onto nature from every room keeps them light and airy. In the master bedroom, a deep brown feature wall with flexible wall-mounted light, orange curtain, grey fake-fur bed throw and a simple black desk by Paul Kafka combine comfort, sensory pleasure and functionality.

The cantilevered cabinet, which spans the rear wall of the living space, was made by Paul Kafka, a fellow émigré from Vienna. The mix of timber, finished in matt black paint, and the reflective qualities of black glass is highly effective.

The dining table, also by Kafka, is surrounded by plywood DCM chairs, designed in 1946 by the influential American industrial designers Charles and Ray Eames.

In 1952, the Rose Seidler House was awarded the highest architectural accolade in Australia, the Sulman Medal. The significance is not to be underestimated, with the establishment seeking a style to call its own for so long. Seidler’s view, according to writer Donald Leslie Johnson, was that his architecture achieved ‘not only a total response to Australia but in complete sympathy, created out of the needs of Australia (society), the site (environment) and that it was logical (rational) and therefore suitable’.

While that may be open to debate, what is incontrovertible is that this house was visionary. So many of its concepts are now commonplace, from the importance of aspect and siting, open-plan living and the integrated kitchen to the painted feature wall, the cantilevered cabinet and insistence on well-designed furniture.

This, Harry Seidler’s first commission in Australia, was as confident a statement as a young architect could make to establish his credentials, and laid the foundations for his career as one of the country’s most eminent and enduring architects.

A floor-to-ceiling curtain ‘wall’ sweeps across and can either extend the living area or create privacy between the living area and playroom.

Seidler directly imported furniture from the US, such as the Saarinen Womb Chair, Knoll Model 70. Artworks by Josef Albers sit on top of the cantilevered wall cabinet.