The land on which Peter McIntyre built his experimental house in 1955 overlooks the Yarra River, Melbourne.

‘You must remember that the postwar nation felt as if it had been let out of a bleak grey prison, so we just splashed colour everywhere, without really comprehending the significance of what we were doing.’

PETER McINTYRE

McIntyre’s original drawing emphasises the bold geometry of the structural design by the use of block colour in primary shades.

The entrance to the house is via a set of stone steps, the rough hewn quality of which contrasts with the precision of the building.

‘This piece of land has dominated my life,’ says architect Peter McIntyre. And when you hear the story, it is true – it has not only dominated his life, but shaped his career. The land in question is 1.6 beautiful hectares right on the Yarra River in the Melbourne suburb of Kew. Here, in 1955, he built the highly experimental Butterfly House…but before the house came the land.

McIntyre came from a family of architects. His father started a practice in 1921, with McIntyre’s uncle joining him in 1930. From the age of seven, Peter McIntyre was running errands and, at 13, was doing advanced drawings. By the time his father enrolled him in architecture, at 16 (overriding McIntyre’s desire to study medicine), he was something of an old hand. Sent out in the spring of 1947 by his father’s office to survey a piece of land for a potential client, he spotted the land directly below, which ran beside the river. He slid down on his backside – access was impossible any other way – and was immediately enchanted. ‘I had been born in Kew and had grown up swimming in the river,’ he says. ‘I was absolutely in love with the river, it was everything, and this was absolutely the most fantastic piece of land.’

He asked a real estate agent to find out who it belonged to and approached the owners with all the confidence of a 19 year old without a penny in his pocket!

The land was a leftover part of the Buchan family’s subdivision of the Finhaven homestead, a mansion that had been demolished, with parcels of land sold off to create Finhaven Court. This piece of inaccessible land was made even less desirable because the bottom part was subject to flooding, and government plans from the 1930s existed for a boulevard from the city out along the river. John Buchan, the executor of the estate, was prepared to sell for £100 but needed the agreement of his brothers and sisters. In the meantime, McIntyre would visit the site, and one weekend while surveying it, a man from a neighbouring house asked him what he was doing. They had tea, and McIntyre talked about his passion for the land and explained that he was buying it. At the next meeting, John Buchan revealed that the neighbour had offered £2000 for it, having previously offered only £10. McIntyre recounted their conversation, and again it went back to the family for discussion. In the end, they agreed to sell it to McIntyre for £400 with a period of six months to pay. He signed a contract on the spot.

When he showed the land to his father, he forbade him to buy it and so McIntyre approached his mentor and friend Robin Boyd. ‘Of course, Boyd fell in love with it himself. At the time he was running The Age Small Homes Service and gave me well-paid work doing amendments to working drawings and perspectives of new houses. I worked night and day, didn’t attend lectures and eventually wore myself out and had to go to bed, sick. My parents found out and my father agreed to pay off the balance, making me work the amount off in his office. I had the land but couldn’t do anything with it.’

That was all to change with the winning of one of the most prestigious commissions in Melbourne at that time – the Olympic Swimming Stadium – and the land played a role here, too. Graduating students in that postwar period seized the opportunity to travel to Europe, Canada and, if they could, the US. All McIntyre’s year went off on the grand tour, but as he was still paying for the land, he couldn’t go. It did mean, however, that he, along with ex-serviceman Kevin Borland, John Murphy and John’s wife, Phyllis, entered the competition for the Olympic pool. ‘It was in my final year when my lecturer Norman Mussen introduced me to prestressed concrete construction and how counterbalancing forces could make economic sense,’ says McIntyre.

On the judging panel were fans of their proposed scheme: Robin Boyd, who defended the aesthetics of their plan, and Professor Francis, in charge of engineering at Melbourne University, who confirmed that it was viable. The scheme utilised high tensile steel post-tension under the guidance of the very experienced structural engineer Bill Irwin. McIntyre is the first to admit the concerns of the architectural establishment around this young team. ‘They did indeed query if we were old and experienced enough to do a structure like that, to pioneer that type of construction and to guarantee that the whole thing would stand up.’ So many dimensions were a given – pool size and seat size – that new thinking was essential to deliver a workable building while significantly reducing the tonnage of steel required in a time of material shortages. ‘Melbourne City Council refused a building permit and we had to go to Sydney to the Building Research Station to have the structure assessed and provide building permits. We had to fight all the way.’

Cantilevering out 12 metres, and 3 metres above ground level, the decks illustrate the combination of lightness and strength that define the building’s construction.

The spiral staircase, against the strong wall colours and ceiling timbers, brings to mind a Russian Constructivist painting.

While this commission kick-started McIntyre’s career as a young gun of the Melbourne architectural scene, it also provided funds to build a house on the land in Kew. Working in the offices in St Kilda at that time was a final-year architecture student, Dione Cohen. She helped with the drawings for the house, and one day asked McIntyre who was going to live in it. His response was to ask her to accompany him to Fawkner Park, behind the office, where he said, ‘Why don’t we live in it together?’ At their 50th wedding anniversary, they went back to the same park bench to ‘plan the next 50 years’.

The house itself is extraordinary and experimental. Putting to use many of the things learnt from the Olympic Swimming Stadium experience, and using the same engineer, Bill Irwin, the house is described by McIntyre as an ‘A-frame double cantilevered truss. Cantilevered in one direction and then balancing that cantilever with the other direction. Essentially putting one force against another.’

The site was difficult to access and, in order to build effectively, explains McIntyre, ‘there was no structural member of the cantilever truss any larger than three inches [7.5 cm]. We were able to fabricate it on the ground in small sections, bring it up by hand, lay it on the side of the hill, bolt it together then stand it up and roll it out.’ The steel frame was filled in with Stramit, a material made of compressed straw, and the surface painted with polyurethane paint in shades of red, yellow and white. ‘You must remember that the postwar nation felt as if it had been let out of a bleak grey prison, so we just splashed colour everywhere, without really comprehending the significance of what we were doing.’ What the vibrant colour and unusual shape did was attract lots of attention. The day they moved in, a feature appeared in The Herald newspaper, and by Saturday morning hundreds of people were coming down the driveway to have a look.

Finished in December when the foliage protected the house, it was a different story come autumn. Suddenly, it was exposed and highly visible from the tram that passed over Victoria Bridge. People would rush to the tram windows to speculate on what sort of a building it was.

Radical from the exterior, it did, however, prove to be a difficult house to live in. McIntyre is the first to admit its shortcomings. ‘Most of the top room was glass to let in the northern sun and boy, did it do that. It also let the cold in as the glass froze – it was like living under a refrigerator. I had to reduce the size of the skylights, insulate the floor and in the early Sixties we clad the outside in hardwood. It was a gradual process of overcoming the inexperience.’

It is important to remember that McIntyre was only 26 when he started designing this, his fourth house. He was also a bachelor with no idea that the house would eventually become home to himself, his wife and four children.

Originally designed in 1960 by Charles and Ray Eames for the Time-Life Building lobbies, the chair was put into general production by Herman Miller a year later.

The kitchen, open to the dining area, uses the same bold colour palette for cupboard doors and inside of the shelving. A Clement Meadmore Cord bar stool sits by the breakfast bar.

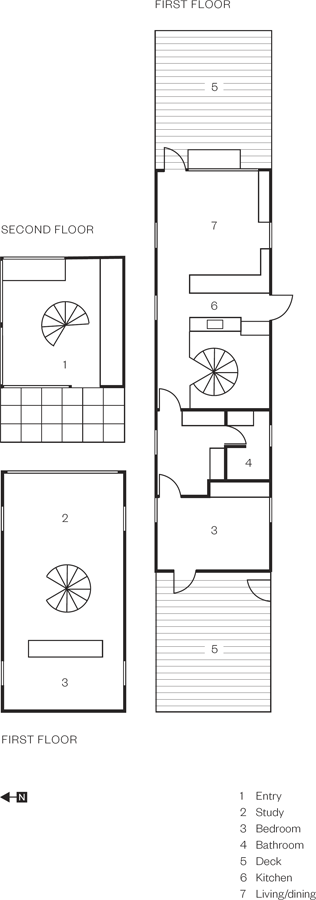

The A-frame construction houses two levels of living space which pivot around a spiral staircase, and allow for generous decks at either side. The rooms are small, but the setting among the treetops is always evident. The triangular form recurs in windows, giving a faceted appearance to interior spaces and, in its highly coloured original state, it is easy to see why the house was compared to a Paul Klee butterfly.

The interior sports glossy red cabinetry in the kitchen and bathroom (which originally had two bathtubs) and bold yellow walls echoing the colour schemes of Charles and Ray Eames. In fact, the house was furnished with the classic Eames lounge chair and ottoman alongside Australian designer Clement Meadmore’s metal and string stools, and Contour chairs by Grant Featherston.

As McIntyre learnt, the difficulty of being at the cutting edge of design was a worrying lack of commissions. He designed a house in Ivanhoe in 1953 for Hans and Pam Snelleman, who lived there for more than 50 years and loved what McIntyre had done for them. But, by 1960 he had no work, so travelled overseas. ‘I realised after winning the pool and doing experimental things, that I really had tickets on myself. I thought it was everyone else’s fault that I didn’t have work. Travelling made me realise what a small fish I was. I had to go away in order to see it. To see how inexperienced I was.’

When he returned, it was with the resolve to change direction and learn more about the building trade. In the following decade, he created an extremely large, successful practice that won many prestigious awards.

This house has survived because it was on land that Peter McIntyre has never left. Other houses, all within the McIntyre family, now share the site, but the A-frame house is testimony to a time of optimism and spirit of experimental thought. In his book Australia’s Home, Robin Boyd sums up the house with a wonderful description. ‘The home of architects Peter and Dione McIntyre on a precipitous bank of the Yarra…symbolised the spirit of the new Melbourne house in the mid-1950s…Form and colour raised the spirits of the converted and deliberately jarred the unconverted into recognition that war was declared on conservatism.’