The courtyard was Boyd’s solution to creating a private outdoor space on a narrow block in a suburban subdivision setting.

It is not hard to see why visiting Japanese architecture students in the late Sixties identified strongly with the building’s aesthetic and why an appreciation of Boyd’s work developed in Japan.

From the street, there are only glimpses of the house, situated behind an enormous pine tree that was on the land when the Boyds bought it in 1957.

Boyd’s appreciation of the Japanese aesthetic is evident from the entrance to the house. The timber steps are open treads and have a measured, proportionally pleasing quality.

In addition to pieces of furniture by Grant Featherston and Clement Meadmore, Boyd designed his own furniture specifically for the house at Walsh Street, including the long, low sofa and complementary coffee table.

The deck extends from the main living space to create an entertaining area overlooking the courtyard garden.

Not only was Robin Boyd a partner in one of Melbourne’s leading postwar architectural firms, Grounds Romberg & Boyd (or Gromboyd, as it was wittily known), but he was also a highly respected architectural critic and social commentator. It is no surprise, then, given his facility with words, that he once described with great clarity what it is for an architect to be his own client. ‘In his own home all his philosophy of building must surely blossom, if ever it is so. Here, he is both playwright and actor, composer and executant. What manner of architect he is will be laid bare for all the world to see…’

Examining Boyd’s Walsh Street residence illustrates many of the traits that define one of Australia’s most influential architects of the period. In 1957, Boyd and his wife, Patricia, had just returned from a year-long trip to the US. As a visiting professor to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Boyd reconnected with Bauhaus movement founder Walter Gropius, whom he had written about in 1953, and met other luminaries of American architecture such as Eero Saarinen, Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. (It is worth noting that Boyd’s erudite writing on Gropius’ work ensured an ongoing friendship, and Gropius was to champion Boyd in years to come.) When Boyd attended an American Institute of Architects (AIA) convention, he noted that all the influential architects spoke with a European accent, confirming the significance of émigrés on the US architectural landscape in the 1950s.

Returning to Melbourne from the States, the Boyds were keen to move to a more central location than their house at Camberwell. Patricia saw an advertisement for land for sale in the upmarket suburb of South Yarra. The owner, Mrs Bishop, anxious about rising land taxes, was keen to subdivide her property and sell the long, narrow block that was originally the rose garden. Boyd, no stranger to awkward sites, saw the land, bought it on the spot and designed this, the second house he had built for himself and his family.

An early proponent of modernism, he saw the technical developments in materials and engineering as the way forward. It was with a great sense of optimism that he talked about the ability to ‘make great open spaces without visible means of support, to throw out parts in cantilever and to open up entire walls to the outdoors through sheets of glass’.

Boyd was also grounded in a belief that well-designed, functional housing was for all, and a decade earlier had devoted years to the development and operation of the Small Homes Service, run by the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects in conjunction with The Age newspaper. Opening postwar in 1947, with Boyd as director, the service offered 40 different house plans for sale at £5 each. An astonishing 1000 were sold, mostly to young couples, in the first nine days, and by 1951 the service was providing plans for more than 10 percent of all new housing in Victoria.

From 1948, Boyd wrote weekly articles for The Age, which increased his public profile. Recruited as a lecturer by Brian Lewis, professor of architecture at the University of Melbourne, Boyd was immersed in architecture in all its facets – practising it, teaching it and writing about it. In 1952, he published his second influential book, Australia’s Home.

Boyd’s work was primarily residential and it is said that he yearned for those large-scale commissions that gave broad recognition to an architect’s career. In 1953, when he was on the jury to select a design for Melbourne’s Olympic pool, he championed his friends and contemporaries Kevin Borland, Peter McIntyre and John and Phyllis Murphy in their submission. Genuinely thrilled at the successful outcome of such a bold, modernist scheme, it did cause Boyd, understandably, to question whether his role was always to be that of persuader on behalf of others rather than take centre stage himself.

As an architect, Boyd was a subtle practitioner. Writer Peter Blake commented that his houses were often ‘almost invisible from the outside: it was the quality of the space inside that counted, not some heroic architectural gestures towards an impressionable world’. In Boyd’s Walsh Street House, there is little sense from the street of what lies beyond. A wall with high windows set behind a pine (that Boyd was at pains to retain from the original garden) is the only visible clue. The house is set back from the street, and wide, open jarrah steps, tapering as they rise to the front door, are protected from the elements by a boldly striped canvas awning. This bridge-style entrance sets the tone for the rest of the house, which feels sensitive and considered, simply designed with a quiet integrity. It is not hard to see why visiting Japanese architecture students in the late Sixties identified strongly with the building’s aesthetic and why an appreciation of Boyd’s work developed in Japan. A red gate and tea-tree fence were added later to stop local dogs using the forecourt as a toilet stop.

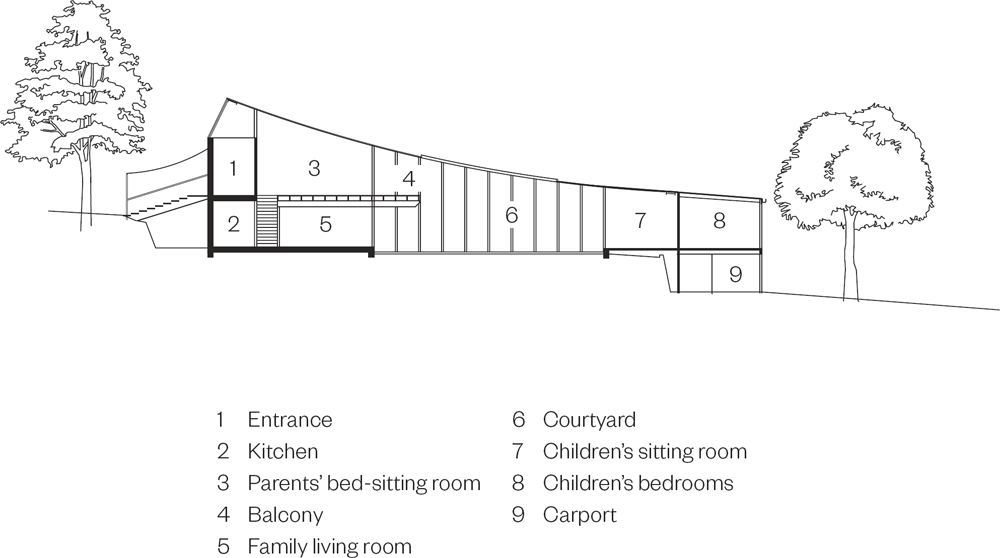

Boyd’s original plan was for a three-storey house but, having spent one noisy school holidays at home with the children, he radically revised the scheme. In his own words, ‘The device adopted was to divide the house in two by a garden square, 40 feet [12 metres] deep, two-storey parents’ block at the front, single storey children’s block at the back. Tall glass walls, partly obscure, partly hooded, were erected on each side of the garden to protect it from wind and most of the rain, but not sun.’

Boyd’s contemporary, architect Peter McIntyre, commented on his ‘sheer inventiveness’ and his ability as a designer to come up with fresh solutions every time. Walsh Street’s construction can only be described as ingeniously simple. A wall two storeys high at the street side and a lower wall near the rear of the block, where the old rose garden finished at a retaining wall, were connected by woven steel cables, slung between the two. Onto these cables were laid timber boards, butted against one another and held in place with nails pierced through the cables, and bent flush underneath. This innovative tension roof structure was protected externally by a bituminous layer which became molten on the day of pouring. Boyd’s practical solution was to add slim timber battens at random to prevent the roof bitumen from seeping through any oversized gaps.

In 1947, Boyd had used builder John Murphy to construct his first home in Camberwell, and he was called on again for Walsh Street. Boyd left drawings sketchy enough that the council wouldn’t ask too many questions, enabling him to push the boundaries of how a home should look and function.

The layout is far from conventional, and must have seemed even more so at the time. It was, however, perfect for the lifestyle of the Boyd family. From the entrance, a long thin dressing room and bathroom lies to the left. Daylight pours in from the row of west-facing windows sitting under the eaves, creating a source of light for both the bathroom and main living area beyond. Separating these two rooms is a partial wall which stops at the base of the windows. A door in the timber wall leads to the main living area. As with their previous house, Patricia and Robin used this room as a bedroom by night and living space by day – something their friends found highly amusing.

The furnishings are spare. There’s a bed which becomes a generous daybed with fitted cover and cushions; twin Featherston two-seater sofas with button backs, which moved with them from their previous home in Camberwell; timber bookshelves, flanking both sides of the room, and a cork-topped coffee table designed by Boyd running parallel to a long, low sofa.

Art played a big part in the Boyds’ lives. Robin Boyd came from a line of distinguished writers and artists, so a variety of artworks decorated the walls. In the dining area, ‘Winter Triumphant’ by Robin’s father, Penleigh Boyd, originally hung above the table, while a portrait of Boyd’s mother by E. Phillips Fox was placed at the top of the stairs. Work by Arthur Boyd, John Brack, Don Laycock, Asher Bilu, Kevin Connor and Tony Woods added to the artistic ambience of the space.

The colour palette, chosen by Patricia Boyd with interior designer Marion Hall Best, is warm and recessive. The internal rear wall was clad in jarrah boards and left unstained, while the bagged brick has been painted a mottled grey. The hit of colour comes from the deep red carpet. The entire breadth of the living area opens to the deck. ‘It is a platform independently supported, emphasising that the whole space enclosed here is one, and in it conventional segregations are neither necessary nor desirable,’ explained Boyd.

Active in the cultural life of the city, the Boyds were very sociable, and Patricia was a celebrated cook. The living room and deck were the main entertaining areas and, on one occasion Boyd, standing below, was alarmed to see the flex in the joists and ushered all but 12 guests back inside. Apparently, feeling that structural engineers were somewhat overzealous in their specifications, he was in the habit of reducing their recommendations.

The corresponding room below the living area is the family/dining/kitchen area. A wall of windows facing the garden illustrates Boyd’s great sense of proportion. The raw timber beams, treated only with a light grey stain, owe a debt to the Japanese vernacular he admired, while the exposure of the structural elements emphasises the honesty of the building’s construction. The limed timber kitchen is discreetly placed at the back of this space, separated from the main living/dining area by the open-tread staircase and a built-in cabinet in limed mountain ash. The cabinet, facing into the room, was designed to house audio speakers and, radically for the period, a TV set.

While the structure for the adults, family living and entertaining provided the hub of the house, at the opposite side of the block, a single storey building was given over to the children’s quarters. It later became known by the children as the ‘other side’, and at mealtimes they were called from their homework by a short ring on the telephone extension. The children’s zone comprised two dedicated bedrooms, a guest room, bathroom and a sitting room/study facing out to the courtyard. The rooms, with the same bagged walls painted warm mottled grey and timber partitions, are simply furnished with built-in desks and neat single beds. Robin’s son, Penleigh Boyd, recalls a degree of freedom in having their own end of the house. ‘We had our own access through the rear lane, a TV room and study space and a view into the marvellous courtyard. We even had a secret basement which was used for storage. Robin also had a passion for cars and we were one of the first families in Melbourne to own a Citroën Goddess. People looked at it as though it was a spaceship. So, all in all, we were a thoroughly modern family.’

Between the two areas of the house lies a garden. As Boyd said, ‘One of the principal objectives in planning was to create a private indoor-outdoor environment despite the narrowness of the allotment and the congested surroundings of an inner suburb.’ These days, we talk of the courtyard as an outdoor room and an extension of our living space as if it’s something new, but Boyd had thoroughly embraced the concept in 1958.

The plan for Walsh Street inspired Mary and Grant Featherston to commission Boyd to design their house a decade later. The Featherston House is a tour de force with its completely integrated indoor garden, floating platforms and translucent fibreglass roof.

The bathroom/dressing room is positioned between the wall that faces the street and the three-quarter height wall that divides it from the living room. It is a long slim space naturally lit by the bank of high windows under the eaves.

Boyd’s ingenuity, illustrated by the Walsh Street House, is an example of his ability to think laterally, to be aesthetically inventive and to solve problems of difficult sites. The James House in Kew (1956) is semi-underground; the Lloyd House in Brighton (1959) is fan-shaped to work around a pear tree; while the Richardson House in Toorak (1953) was designed as a bridge over a dry creek bed. He produced an enormous range of housing in his career and embraced the possibilities of new methods of construction to realise his concepts.

His writings on architecture and society challenged and shaped popular opinion, and his work The Australian Ugliness (1960) pulled no punches in its attack on certain aspects of popular taste. He wasn’t afraid to take Australia to task, especially in its increasing Americanisation, and endeavoured to make the country strive for its own, distinctive cultural identity.

His reputation as a writer grew when, at the recommendation of Walter Gropius, a New York publisher commissioned Boyd to write a short biography of Japanese architect Kenzo Tange. Tange’s comment, ‘I could not help admiring you for your deep understanding and correct criticism on Japanese culture as well as my own work’, goes some way to show Boyd’s sensitivity and ability to tune in to the work of another architect in another culture.

Boyd may have felt disappointed that his career did not embrace large-scale commissions, but in many ways he played an even more significant role in the development of Australian architecture. He acted as the gatekeeper for aesthetic standards and played a crucial intermediary role, through his writing, between the profession and the public. As Joseph Burke said of Boyd after his untimely death in 1971 at the age of 52, he was ‘the artistic conscience of his country, in the future of which he passionately believed’.

The Walsh Street House is the property of the Robin Boyd Foundation. The Foundation was established by the National Trust of Australia (Victoria).

The study area in the children’s zone featured the same bagged brick walls and simple functional furniture as used elsewhere. As Penleigh Boyd recalls, there was an enviable degree of freedom in having their own end of the house.