Chapter 7

Active Surveillance

Overview

- Active surveillance (AS) is a management option in prostate cancer, the primary aim of which is to avoid unnecessary treatment in men with indolent cancers

- AS is an intervention undergoing evaluation and awaiting level one evidence from randomised control trials (RCTs) for safety and quality of care to support its use

- AS is an option for carefully selected low risk patients who are candidates for curative intervention should clinical parameters indicate that the disease is no longer indolent

- In general, AS protocols require regular clinical examination, PSA testing and repeat prostate biopsy

- Limited published follow-up is available for patients on AS protocols, the results of several RCTS are awaited

According to Cancer Research UK (2010), prostate cancer (CaP) is the most common cancer in men in the UK. However, it is clear that a significant proportion of patients diagnosed with CaP will never develop symptoms nor see a reduction in their life expectancy due to the disease. In addition, we know that treatments for CaP may actually cause significant morbidity, including urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction and an increase in cardiovascular morbidity. It is therefore vital that intervention for CaP is offered in a timely fashion to those who will benefit while treatment is deferred in those who will not. Some statistics on prostate cancer risks are:

- The lifetime risk of dying from CaP is 1 in 33.

- The risk of a man over 50 years of age being diagnosed with CaP is 1 in 6.

- The risk of a man over 50 years of age having histological evidence of CaP is 1 in 3 (on autopsy).

It can be inferred from these figures that the incidence to mortality ratio is almost 8:1. It could be argued that this corresponds to a degree of over-diagnosis, i.e. patients being diagnosed with CaP when the disease will not affect them clinically nor shorten their life span.

Active surveillance (AS) is a methodology of patient monitoring with the primary aim of avoiding unnecessary treatment in men with indolent cancers. Follow-up ideally identifies those patients who have progressive cancers at a stage where intervention will still be curative. It is therefore indicated in those who have potentially curable disease but do not require this at the time of diagnosis or in those who wish to defer intervention for as long as is safe, with the aim of avoiding the complications of intervention. It may also be used as part of a treatment strategy in those who intend to undergo curative treatment but wish to defer this for a period of time until circumstances allow.

Why is active surveillance an option in prostate cancer?

From 1990–2002, the annual age-adjusted incidence of prostate cancer increased twofold. This increase was largely due to PSA testing enabling the detection of low-grade, low-volume (<0.5 cm3) and impalpable disease in asymptomatic men. This corresponds to considerable lead-time bias, reported as between 9.9–13.3 years, as tumours are diagnosed well before they may become clinically relevant. Although the natural history of prostate cancer is heterogeneous, and not fully understood, it has been argued that around 60% of these men would not experience clinically significant progression during their lifespan due to age at diagnosis, competing co-morbidities or low-grade tumour status. Active surveillance aims to identify this group who will not develop clinically significant disease, sparing them the morbidity of over-treatment, while identifying those in whom disease progression is likely.

What is the difference between active surveillance and watchful waiting?

Watchful waiting is an approach usually employed in elderly men with significant co-morbidity who are asymptomatic. It is the postponement of therapy (usually hormone manipulation) until symptoms occur with the intention to palliate CaP rather than attempt to cure it, as with active surveillance.

How is active surveillance undertaken?

The inclusion of AS in the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines (2008) infers that there is consensus on the method of AS when, in actual fact, none exists. AS is an intervention undergoing evaluation and awaiting level one evidence from randomised control trials for safety and quality of care to support its use.

The common features of the differing protocols include:

- regular physical examination (including digital rectal examination, DRE);

- regular serum PSA;

- repeat prostate biopsies.

The ideal interval between investigations is unknown and is the subject of current study. A typical regime would involve three-monthly PSA estimations, six-monthly DREs and repeat prostate biopsy at between one and two years after initial diagnosis. This regime would continue in those who remain stable with no evidence of clinical, biochemical or histological progression. Around 10% of patients opt out of active surveillance programmes out of choice, unwilling to live with the perceived degree of uncertainty this type of monitoring incurs.

What is the evidence for active surveillance?

If we extrapolate data from patient groups from the pre-PSA era, a significant proportion with low-grade, low-volume disease who are initially identified by PSA screening alone will have a longer than 20-year disease-specific survival with no treatment. Current data support this hypothesis but, however, are derived from non-mature randomised controlled trials with follow-up of less than 10 years. These AS studies in patients with CaP (predominantly identified by PSA screening rather than those presenting with symptoms or abnormal clinical examination) consistently show low rates of tumour progression and high rates of disease-specific survival (10-year CaP specific survival rates of 99–100%). In the same studies, the proportion of patients opting out of AS protocols to undergo intervention ranges from 14–31%. However, the median range of follow-up in these patients is 24–64 months and longer-term data are awaited. Several international studies are under way, including Standard Treatment against Restricted Treatment (START), Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProTeCT), Prostate Cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial (PIVOT) and Prostate cancer Research International: Active Surveillance (PRIAS).

For which patients is active surveillance an option?

Serum PSA, tumour grade and tumour volume may be used to predict risk of progression of CaP. Current nomograms (of which there are at least 40 published variants) tend to be based upon follow-up of patients who have undergone radical intervention for CaP, usually radical prostatectomy, as tumour grade and volume can be reliably measured in this group. However, the tools presently available provide a guide only and must be tailored to the individual.

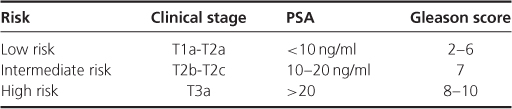

The majority of guidelines on active surveillance use the risk stratification parameters described by D'Amico and colleagues which have been validated in patients undergoing both radical prostatectomy and radical radiotherapy. Each risk category describes the risk of CaP-specific progression at 10 years (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Risk categories for CaP-specific progression at 10 years.

Both the American and European Urology Associations recommend that active surveillance is discussed with low and intermediate risk prostate cancer patients. In 2008, NICE produced guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of CaP. Active surveillance was recommended as first-line treatment for men with low-risk CaP. In response to concerns raised by UK urologists and oncologists due to the lack of long-term data on this treatment option, a joint NICE and British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS) statement was subsequently issued, confirming that all management options should be discussed with low risk patients.

Several other variables are considered in addition to the clinical stage, PSA and tumour grade. These depend upon the AS protocol employed and include:

- the percentage of positive cores taken at trans-rectal guided prostate biopsy and percentage of maximal core involved with prostate cancer;

- PSA kinetics—including the estimated time for the PSA to double (doubling time) vs. PSA velocity and percentage of maximal core involvement (<50%);

- PSA density (the PSA normalised for prostate volume estimated with trans-rectal ultrasound);

- patients must be fully motivated to participate and understand that follow-up visits are mandatory in order not to miss possible tumour progression.

Benefits of active surveillance

AS is attractive to patients due to the lack of side-effects associated with curative treatment options. Many men with low-volume, low-grade disease will never need treatment, and elderly men will often die of another medical condition before their prostate cancer manifests clinically.

Potential risks of active surveillance

Determining which men are at greatest risk of disease progression is challenging. Most centres operate on a combination of Gleason grade, PSA and clinical stage. There are currently studies comparing the velocity of PSA rise with PSA doubling time and considerable debate still arises as to which is the most accurate predictor of progression.

As the prostate cancer is not actually being treated, there is always the possibility of disease progression that could ultimately lead to death. A more advanced stage of disease at a later date may have limited treatment options open to the patient with more unpalatable side-effects. Careful selection of patients onto an active surveillance programme is vital. Patients must be highly motivated and prepared for the degree of commitment that entering into an active surveillance programme entails.

There is also the degree of psychological stresses that occurs due to the knowledge of being diagnosed with cancer without actually being treated for it. A proportion of patients find this unacceptable and decline AS for this reason. Studies have shown that having dedicated nurses for this patient group significantly decreases this anxiety by providing the reassurance of having easy access back into medical care.

When to identify that the disease has progressed?

Identifying significant disease progression is the key to successful AS and the ability to offer radical treatment while the condition is still curable. Many different regimes have been published and there continues to be a lack of cohesion in deciding an appropriate regime. Most agree that the following are important:

- change in DRE;

- rising PSA—either PSA velocity or doubling time. CaPSURE demonstrated this was the greatest trigger for active treatment. However, the randomised control trial from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Study Group showed that it was unsafe to use PSA kinetics in isolation as a marker to exclude disease progression.

- increased Gleason grade;

- increased tumour volume on biopsy, though the debate as to which is most reliable of standard trans-rectal biopsy versus trans-perineal template and saturation biopsies remains.

The role of serial imaging is under investigation.

The decision to progress from AS to radical treatment should be made with the patient and based on co-morbidities, life expectancy and personal preference.

There has been considerable interest in the use of novel biomarkers for predicting the behaviour of individual tumours, e.g. TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion, which may predict a more aggressive disease phenotype. Gene signatures including gains 11q13.1 and deletions 8p23.2 have been shown to predict PSA recurrences post prostatectomy, irrespective of grade and stage of primary tumour.

Active surveillance is an alternative to immediate treatment of localised prostate cancer in men with presumed low-risk disease. Cancer registry data suggest that active surveillance is a currently under-utilised treatment option. This is in part due to concerns of missing clinically significant disease progression. Medium-term studies seem to confirm that in carefully selected men, delayed treatment does not appear to compromise outcomes for these patients, however, prospective studies of AS entry criteria are required in order to standardise the definition of ‘low-risk’. Long-term data from studies such as ProTeCT, START, PIVOT and PRIAS are awaited.

AUA Guidelines for the Management of Clinically Localised Prostate Cancer, 2007. (www.auanet.org).

Bastian, PJ et al. Insignificant prostate cancer and active surveillance: From definition to clinical implications. European Urology 2009;55:1321–32.

Dall'Era MA et al. Active surveillance for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer 2008;112(8):1650–9.

EAU Guidelines on Prostate Cancer, 2010. (www.uroweb.org).

NICE Clinical Guideline 58, Prostate Cancer, Diagnosis and Treatment. February 2008. (http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG58).

Weissbach L, Altwein J. Active surveillance or active treatment in localised prostate cancer? J. Deutsches Artzeblatt International 2009;106(22):371–6.

Wilt, TJ, Thompson, IM. Clinically localised prostate cancer. BMJ 2006;333:1102–6.