Compared to the prickly pear opuntias, the wrasse, the boobies, the weevils, finches and iguanas, humans came late to the Galápagos. But like all of the settlers before them, humans reached these islands by accident rather than design, swept out from the South American coast—against their will—on what we now call the South Equatorial Current. They also did so by rafting. What, after all, is a Spanish galleon if not a mat of (admittedly rather special) vegetation?

It is possible that this first ship was more like a canoe and belonged to the pre-Columbian people of modern-day Ecuador or Peru. There are certainly those in both countries who claim their own Amerindians were the first to reach the Galápagos. If they were, however, there is—as yet—no compelling evidence, and the bishop of Panama’s fleeting visit in 1535 is the first to be documented.

Once safely back in Lima, the bishop wrote a report of his Galápagos misadventure to King Charles I of Spain. ‘The Lord fill Your Sacred Majesty with holy love and grace for many years and with the conservation of your realms and an increase of other new ones, as I hope,’ he wrote, though there was no recommendation that the Galápagos should be one of them. ‘I am your most true servant and subject and perpetual Chaplain, who kisses your royal feet and hands.’

It is from the accounts of the bishop and those who followed that the islands got their name. In the Geography and Map Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, there is a stunning sixteenth-century chart of the South American coastline from Guatemala to Peru with significant landmarks scratched onto a rectangle of cow hide in black, blue, green and red inks. It’s easy to make out modern-day Panama City, Bogota, Quito and Lima, urban centres all marked with little cartoon-like palaces. All the way along the coast, offshore islands—obvious hazards to the nautical folk who would have been using this chart—are flagged up in red. Further out to sea, all alone, is a collection of twelve elongated blobs, and projecting downwards in elegant script are the unmistakable words ys de galapagos.

It’s often said that galápago was the medieval Spanish word for ‘saddle’ and that the islands were therefore named after the exaggerated saddle-shaped shells of several of the tortoise species. In fact, as historian John Woram has made clear, it was the other way round. Galápago meant ‘tortoise’, and the silla-galápago (which turned up as an equine accessory in Spanish literature in the nineteenth century) was a tortoise-shaped saddle.

So the ys de galapagos are the ‘islands of the tortoises’. It’s an appropriate name. The accounts of all early visitors reveal that the giant tortoises made a deep impression. Sadly, these creatures served another, more utilitarian purpose. The palpable excitement of those who dined out on their flesh persuades me that these creatures must taste good. For the next three centuries, the principal reason for setting foot on the Galápagos was to take stock of these palatable reptiles.

One of the first to wax lyrical about the taste of Galápagos tortoises was the buccaneer William Dampier. ‘They are extraordinary large and fat; and so sweet, that no Pullet eats more pleasantly,’ he wrote in 1697. James Colnett (he of the British whaler HMS Rattler) sung the praises of their ‘excellent broth’. Amasa Delano, a US Navy captain who described his visit in 1801, felt that ‘their flesh, without exception, is of as sweet and pleasant a flavour as any that I ever eat’. In 1813, another US Navy captain, David Porter, was even more gushing: ‘Hideous and disgusting as is their appearance, no animal can possibly afford a more wholesome, luscious, and delicate food than they do,’ he wrote. Although Darwin judged tortoise meat to be ‘indifferent food’, he conceded that when roasted on the bone in the manner that South Americans roast their beef, ‘It is then very good.’ Moreover, ‘Young Tortoises,’ he claimed, ‘make capital soup.’

It was not just the meat that excited these men. According to Dampier, one party that had feasted on tortoise meat for some three months ‘saved sixty Jars of Oyl’, which once back at sea ‘served instead of butter to eat with doughboys or dumplings’. Delano gave a more accurate sense of how much fat could be collected from one animal. Besides that used to fry up the meat, ‘it was common to take out of one of them ten or twelve pounds of fat,’ he wrote. ‘This was as yellow as our best butter, and of a sweeter flavour than hog’s lard.’ Porter concurred. The fat, he found, ‘does not possess that cloying quality, common to that of most other animals’ and ‘furnishes an oil superior in taste to that of the olive.’

The giant tortoises proved to be a handy source of liquid refreshment too. ‘They carry with them a constant supply of water, in a bag at the root of the neck, which contains about two gallons; and on tasting that found in those we killed on board, it proved perfectly fresh and sweet,’ wrote Porter.

There is, however, another, less sapid reason why the Galápagos tortoises suffered more than most: their cold-blooded nature means they can drop their metabolism, and with an inbuilt supply of water, they are able to survive up to a year without food or water. In a world before freezers, giant tortoises were a godsend. ‘They were piled up on the quarter-deck for a few days . . . in order that they might have time to discharge the contents of their stomachs,’ explained Porter. Then he had his men carry them below deck and stored ‘as you would stow any other provisions’. Writing about his experience of the Galápagos in 1825, Benjamin Morrell asserted that a hoard of tortoises would provide ‘fresh provisions for six or eight months’, protecting the men from scurvy into the bargain.

This combination of tastiness and hardiness resulted in tortoise slaughter on an absolutely staggering scale. Privateers like Dampier, whalers like Colnett, naval officers such as Delano and Porter, and explorers like Morrell weren’t just hungry—they were very, very greedy.

The collection of tortoises was something of a military operation. ‘All hands employed in making belts to go after terpen,’ reads the entry of one whaling logbook. ‘Four boats were dispatched every morning . . . and returned at night, bringing with them from twenty to thirty [tortoises] each,’ wrote Porter of a particularly profitable visit to Santiago in 1813. ‘In four days we had as many as would weigh about 14 tons on board, which was as much as we could conveniently stow.’ This would have been just shy of five hundred animals. On another occasion he recorded ‘getting on board between four and five hundred’ from Floreana.

Whilst such hauls seem to be the exception rather than the rule, most vessels would typically take dozens and often hundreds. In an analysis way ahead of its time, director of the New York Aquarium Charles Haskins Townsend sat down in the 1920s to pore over the logbooks of American whaling vessels and found several similarly startling harvests. The crew of one vessel, for instance, spent just five days on Española and came away with 335 animals. Another took nine days to reap 350 from Floreana. A third took as many days to secure 240 tortoises from San Cristóbal. There is the odd document that captures how backbreaking this must have been for the sailors. ‘We got about 250 altogether which cost us much trouble,’ wrote one. Another confessed to being ‘tired oute’ by the exertion. Yet another still found himself ‘intirely exhoisted’.

By the time he’d finished, Townsend had extracted tortoise tallies from the logbooks of seventy-nine American whalers that had made 189 collecting trips in the Galápagos between 1831 and 1868. In just thirty-seven years, these hunters had removed a minimum of 13,013 giant tortoises from the islands. As this was only a fraction of the American fleet and captured none of the exploitation carried out by British whalers, Townsend knew it was a gross underestimation of the toll. ‘It would be within safe limits to credit American whalers with taking not less than 100,000 tortoises subsequent to 1830,’ he concluded. We can never really know the full extent of the devastation, but factoring in the activities of the British whaling fleet and the likes of Porter, this phase in the history of the Galápagos could well have seen the extraction of 200,000 giants. Or more.

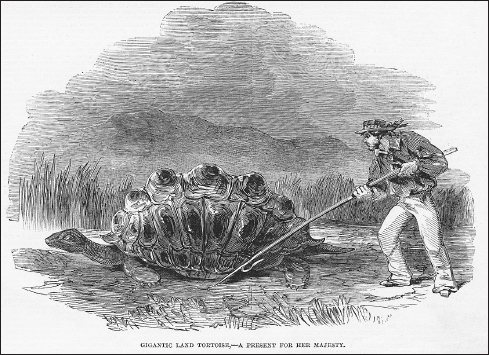

FIGURE 8.1. The Galápagos giant tortoises tasted good. It’s thought that buccaneers and whalers may have eaten their way through several hundred thousand giant tortoises. Reproduced from the Illustrated London News, 13 July 1850, courtesy of John Woram.

Whilst he was about it, Townsend did the same for fur seals. The few snippets of evidence he could assemble suggested sealers had taken at least 20,000 animals from the archipelago between 1870 and 1882. ‘This is of course a trivial number as compared with the total catch made during the period, the records of which are not available,’ he wrote. By the time he first visited the Galápagos in 1888, only a few fur seals remained.

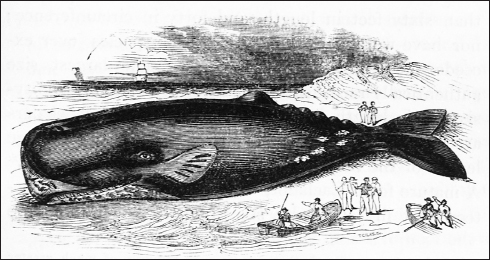

FIGURE 8.2. The sperm whale. Sperm whales were big business in the nineteenth century, and the Galápagos was one of the best whaling grounds around. Reproduced from Charles Nordhoff, Whaling and Fishing (Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach, Keys & Co., 1856).

By then, the whale population had been decimated too. In the days before the discovery of petroleum in the 1850s, whales had been of enormous commercial value. Oil refined from whale’s blubber had provided the most common source of fuel for artificial lighting; it was used to grease up factory machinery and clocks; whalebones were fashioned into canes, corsets and ribs for umbrellas. The sperm whale was of particular value owing to the pearly, ejaculate-like fluid (hence called spermaceti) contained in an unusual cavity in its rectangular head (the spermaceti organ). There’s still debate over what purpose this cavity serves the whale: it could be used to control buoyancy; it might be used as a battering ram to stun its prey; or, more likely, it serves some complex acoustic function. The whalers, however, were interested in none of this. Once bailed out from the sperm whale’s head and processed, the spermaceti yielded a particularly clarified product suitable for making the finest of candles and the most coveted of cosmetics. In around 1820, when the whale industry was in full swing, spermaceti oil was worth twice as much as bog-standard blubber oil.

In comparison to the decimation of the giant tortoises, fur seals and whales, the decision of humans to live in the Galápagos from the nineteenth century onwards seems innocent enough. But the way in which this settlement played out over the course of the next two centuries is nothing short of remarkable.

Potatoes and Pumpkins

The early efforts to colonise the Galápagos were slow and fraught. The first person to call the Galápagos home is thought to have been an eccentric Irishman called Patrick Watkins, marooned on the island of Floreana in 1806. ‘The appearance of this man, from the accounts I have received of him, was the most dreadful that can be imagined; ragged clothes, scarce sufficient to cover his nakedness, and covered with vermin; his red hair and beard matted, his skin much burnt, from constant exposure to the sun, and so wild and savage in his manner and appearance, that he struck every one with horror,’ wrote Porter. In the years to follow, Porter’s second-hand account spawned several third-hand versions of the Watkins story, most notably Herman Melville’s ninth sketch of the islands. ‘He struck strangers much as if he were a volcanic creature thrown up by the same convulsion which exploded into sight the isle.’

Watkins lived in a hut around a mile inland from what is now Puerto Velasco Ibarra, the small settlement that opens onto the appropriately named Black Beach on the west coast of Floreana. Porter was fascinated by this character, describing how he managed to survive in solitude, growing his own vegetables and trading them with passing ships in exchange for rum. ‘We have seen, from what Patrick effected, that potatoes, pumpkins, &c., may be raised of a superior quality, and with proper industry the state of these islands might be much improved.’ Few people had Porter’s vision that the Galápagos might be ‘improved’. Yet within a couple of decades, a man with a plan did come forward. Louisiana-born José María Villamil had fought hard against Spanish occupation of South America and is one of Ecuador’s founding fathers. Upon Ecuador’s gaining independence in 1830, Villamil urged the country’s first president, General Juan José Flores, to stake a claim on the Galápagos, proposing to set up a small colony to harvest Roccella tinctoria (an abundant lichen and good source of the valuable purple dye orchil) for export to the mainland. Flores agreed, and Villamil became the first governor of the island. An advance party of a dozen men reached Floreana in January 1832, and a small ceremony on 12 February formally marked Ecuador’s acquisition of the archipelago. This is Galápagos Day, a public holiday in the islands that rather wonderfully happens to coincide with Darwin’s birthday.

One of the first reliable accounts of Villamil’s endeavours comes from Jeremiah Reynolds, a US naval officer on board the frigate Potomac. This reveals, in no uncertain terms, the power that humans have to transform a landscape. Within a year of Villamil’s arrival in October 1832 with around one hundred men at his disposal, Reynolds judged that ‘the productions of the island are sufficient for several hundred additional inhabitants’. The luxuriant centre of the island boasted soil that ‘may be cultivated from January to December, one crop following another in rapid succession; moistened in summer by continued and heavy dews, and by rains in winter’. From a vantage point in the highlands, Reynolds looked down upon Asilo de la Paz (‘Refuge of Peace’), ‘no less than fifty little chacras, or farms, with nearly an equal number of houses’. At a small party held for the visitors, the only beverage on offer was water drawn from the ‘Governor’s Dripstone’ and other freshwater sources that spring from the mountainside. It looked like Villamil’s venture was to be a great success, something Reynolds put down to his strict no-alcohol policy.

By the time HMS Beagle appeared on the horizon a couple of years later, Villamil’s settlement had roughly doubled in size. With his boss absent, Vice-Governor Lawson (he with the interest in tortoise morphology) led Robert FitzRoy and Charles Darwin from Black Beach up to the new settlement in the highlands. Both men were impressed by its productivity. ‘Surrounded by tropical vegetation, by bananas, sugar canes, Indian corn, and sweet potatoes, all luxuriantly flourishing, it was hard to believe that any extent of sterile and apparently useless country could be close to land so fertile,’ wrote FitzRoy.

Although Villamil’s fledgling enterprise folded within a couple of years and there’s little left of the original settlement, the wider impact of this agricultural enterprise is only too obvious. In a matter of years, the seeds that would undermine Floreana’s ecological integrity had been set.

The impact of introduced mammals is even more obvious. In his summary of the efforts at farming on Floreana, Reynolds also noted that the lower, drier portions of the island would be ‘good for raising hogs, goats, &c’. There are now thirty species of vertebrates known to have been introduced to the Galápagos by humans, and most of them have been very bad news. Darwin appreciated the impact that aliens could have on native species, noting ‘what havoc the introduction of any new beast of prey must cause in a country, before the instincts of the aborigines become adapted to the stranger’s craft or power’. At the last count, there were also 536 introduced invertebrates (at least), several of which—like the little fire ant considered in the next chapter—have had a highly destructive influence.

Invasive plants are a lot harder to demonise than rats and insects. Indeed, the list of plants that humans have introduced to Floreana and the other inhabited islands in the Galápagos (870 species, according to the latest reckoning) gives off a luxuriant scent: guava, hill raspberry, quinine, rose apple, avocado, orange, lemon, lantana, angel’s trumpet, bamboo, balsa, and so on. But the damage caused by these species is tremendous owing to the simple fact that the only place suitable for their cultivation is the damp, species-rich highlands (which explains why Villamil set up camp in the centre of Floreana rather than on the coast and why the early settlers on each of the other inhabited islands were quick to turn the most productive humid zone over to the plough).

A recent study of satellite images suggests that over half of the highland area on the four inhabited islands (almost 300 km2 in total) has been completely transformed by agriculture. On Floreana, some of this habitat is recovering after the removal of its large invasive mammals, but the situation on Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal is not so good. On San Cristóbal, for instance, more than 95 percent of the highland habitat is seriously degraded as a result of the nearly continuous presence of humans for more than 150 years. This began in the 1850s, when another entrepreneur, Manuel Cobos, set up a commune called ‘El Progreso’ with the intent of farming lichen (just as Villamil had attempted on Floreana). They ended up growing sugar cane and coffee, but the project ended in disaster, the (largely convict) workforce rising up to kill its punitive foreman in 1904.

FIGURE 8.3. El Progreso in the highlands of San Cristóbal. Entrepreneur Manuel Cobos created this settlement in the 1850s, where his largely convict workforce tended plantations of sugar cane and coffee. Reproduced from the NOAA’s Historic Fisheries Collection.

Specimen Collections

Whilst all this was happening, another force impoverished the Galápagos, in the short-term at least: science. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, several scientific expeditions—mostly from Britain and the United States—charted a course for the archipelago to collect its plants and animals for zoos and museum collections. In 1905, the California Academy of Sciences carried out the last and by far the largest efforts to catalogue the natural productions of the islands. Their total haul of more than 75,000 specimens (including 264 giant tortoises) was greater than all previous expeditions combined. By today’s standards, this might seem like a shocking statistic, but this was over one hundred years ago. If it appears as though these men had no conservation mindset, it’s because they didn’t, and nor did anybody else at the time. But they were concerned about extinction, which they considered a very real possibility for several of the unique species, especially the giant tortoises. The purpose of the expedition, according to the California Academy of Science’s herpetologist Joseph Slevin, was ‘to make an exhaustive survey, most extensive collections, and, most of all, to make a thorough study of the status of the gigantic land tortoises before it proved too late’.

In this goal, they succeeded and these collections—as epic as they were—have turned out to be of vital importance to the conservation movement that began to emerge in the 1950s. Without the historical background provided by the collections of the California Academy of Sciences and others, it would have been hard to think sensibly about conservation in the Galápagos.