September, Ocala, Florida

“That one. The big black colt over there.” Bob pointed toward me. “Of all of the weanlings, he’s something special. Watch him trot. He floats — like a ballet dancer crossed with an F16 fighter jet.”

I showed off, arching my neck and flashing my feet as I trotted. Bob leaned against the fence watching us, his faded jeans and scuffed cowboy boots dusty from the day and his well-used bandana hanging out of his back pocket. His friend, Michelle, stood next to him, with Piewacket and Muttley, her Jack Russell terriers, at her feet, devotedly following her every move with quick, alert ears.

“He’s going to win the Kentucky Derby. It’s destiny. Princess Ayesha even told me he has ‘special whorls’ that say so, see?” He pointed at my forehead, smiling.

“Bob, don’t poo-poo that — some people swear by reading horse’s whorls. Maybe there’s something to it. I don’t know much about them, but I agree. He’s a nice colt.” Michelle’s blond ponytail bobbed as she jumped up in a single athletic motion to sit on the fence and watch me. I felt her focus, first uncomfortable at such intimacy, then settling into her admiring gaze. Her intensity surprised me as we connected more like two horses, direct and honest and wordless, straight to the heart.

“Seriously, Bob, he’s got charisma. The good ones always do. My horse, Holzmann, has it, and your colt reminds me of him.”

“The one who won the silver at the Olympics?”

Michelle nodded. “Raja has the same look of intelligence. They call it the ‘look of eagles.’ I think Raja wants to be a jumper and take me back to the Olympics,” she laughed.

“Way-ell, now,” Bob drawled, a sly smile creeping across his face as he scratched his ear and pushed his cap forward over his forehead, “and how would you pay for the millions he would cost without sending him to stud?”

December, a year later, Ocala, Florida

“El peligroso,” the dangerous one. That’s what the stable hands called Max after two of them were sent to the doctor with injuries from his well-aimed hooves. I suppose every riding horse has to go through it, but I’m not saying it was fun. Almost everything was just plain uncomfortable: learning to wear tack — heavy, tickly saddles and bridles with heavy cold metal bits in our mouths; having our hooves trimmed by the farrier; and walking up a ramp into a stall on wheels, the horse van.

We tolerated most things now that we were almost two, living in the barn and being “broken in,” but it was all slightly trying, especially for Max, who definitely didn’t like being told what to do.

“You gotta outwait ’em,” Bob told Chris, his new young assistant, who was learning about training. “Sooner or later they come around if they understand what you want them to do. Reward them when they get it right. They’re smart; they know.”

A familiar, calm smile starting with the crinkles at the corners of his eyes met any high spirits, as Bob waited patiently — no words, just a look that seemed to say, “You really want to make an issue out of this little thing?”

Usually we just ended up doing what he wanted because we were tired of being asked again and again and again. And, of course, there were carrots involved.

Carrots help a lot.

“Vet’s comin’ tomorrow to tattoo their upper lips. The inside, see here.” Bob put his hand on the upper lip of a horse down the shed row from me and rolled it up to show Chris. “See that letter? It’s the year he was born. The number after is the last five digits of his Jockey Club registration number. That’s the way Thoroughbreds are identified. They have to be registered and tattooed before they race — that’s why they all have unique names.”

Chris grimaced. “Ouch, sounds painful.”

“Don’t worry, they only feel a prick.”

Soon all of us two-year-olds were training on the dirt track, galloping side by side, four sets of nostrils breathing in stride or bucking and egging each other on.

Starting-gate lessons were the best. We walked into the narrow metal stalls, hearts pounding, muscles taut and ready to go, feeling more alive than I thought possible, knowing it would soon be time to gallop! Watching the gate person intently, filling our lungs with a deep breath. And when you couldn’t bear to wait any longer, exploding onto the track, fighting to get out and away first, bodies bumping and hot wet sand flying in our faces.

Max and I galloped head to head. Toward the end, I would look him in the eye.

I dare you to try to beat me.

He always fought fiercely and I always played with him for a while — like the barn cats with a mouse they were about to kill. Then I turned on what Bob called “the afterburners” and blew by him — to keep him in his place.

“Como estas, Raja, how are you today? Are you going to win the Derby?”

Every day, Pedro, my regular exercise rider, greeted me with a grin that took over his weather-beaten face and made everyone in its beam feel as if they were the best thing to happen to him. A mischievous gleam in his eye invited you to share the joke while he innocently rubbed the back of his nearly bald head.

“Only forty years old and I’ve broken 20 bones — my collarbone four times.” He winked at Chris. “I don’ think I have any more left to break. I love working with all of the Sheikh’s babies. It’s so much easier when you start with class. These boys are the top, I’m tellin’ ya. You couldn’t teach a horse what they’ve had bred into them — power, boldness, heart. One of these boys could be the next Secretariat or Man o’ War.”

We had a routine. Pedro usually brought me an apple or a sweet pastry. I greeted him and rubbed my head on his shoulder, trying to find the treat.

“Hey buddy, you look like a big, tough racehorse, but you’re just a puppy dog.”

Ta-da-da-dum, ta-da-da-dum, ta-da-da-dum.

I felt Pedro’s joy, like warm sunlight, as we galloped together, the two of us chasing down the dirt training track on the mist-filled mornings, with his steady hold and light and even balance floating over my back. By now, I was strong and getting fitter and I wanted to go, go, go.

Sometimes we had a little “conversacion,” as Pedro called it, about how fast we should be going. He always made sure that I came around to his point of view sooner or later. When I saw Pedro, I took a deep breath and relaxed. He was interesting, the way he was so calm and easy, but with fire and steel inside, ready if I acted tough, which was often. Mostly, he tried to teach me that the two of us were a team, better together than separate.

Working! Breezing!

If you really want to understand me, you have to know about working. There’s nothing, I mean nothing, better, except maybe actually racing. Most days we galloped or jogged, but on Saturdays, we got to turn it on! First, gallop a turn, around the middle of the track at a two-minute lick. Then, drop to the inside rail — the signal to GO! The wide-open dirt track coming faster and faster until it turns into a blur, no sound but the wind rushing by my ears; Pedro’s hold is strong and tight as he crouches lower, moving in rhythm with my longer and longer strides until we begin to fly, skimming the ground.

Then, with a shift of his weight, Pedro stands in his stirrups and the moment is over. Hearts pounding and catching our breath, Pedro laughing, the colors more intense, sounds sharper, I feel happy, more alive, somehow. I know Pedro felt it too. That’s why we got on so well. We both loved, I mean, loved, speed.

It was a Monday, our day off, and Pedro and Bob were off with the horse van, leaving Chris and Ken, the second-string exercise rider. Chris moved a little more slowly than usual, cleaning the tack and folding saddle towels as he sang along with the radio. When he finished the tack, he started making his way down the shed row, taking off stable bandages and leading horses out one at a time to hand walk and graze.

“Looks like we might get some weather,” Chris pointed to the grey clouds that had taken over the sky.Ken, muttered something angrily to Chris in response.

Ken always seemed ready to explode. He stomped around the barn and got all of us horses riled up when he came to ride. Thankfully, I didn’t have much to do with him.

“Figures they’d pick a rainy day to leave us to do all the barn work. Typical. That Pedro thinks he’s god’s gift to horses. Well, he ain’t. I’m just as good as Pedro. Better, in fact. He’s a tired old man. These people are stupid. I’ll show ’em, I’ll show everyone.”

A wild, cloudy look swept across Ken’s darting eyes as he ranted, nervously scratching his scraggly beard, then spitting out his chewing tobacco juice in a long brown spurt aimed at the cat. He walked over to my stall.

I lifted my head suddenly and backed up as Ken jerkily raised his arm toward me, then slapped my neck, thinking he was patting me. I flinched, holding my breath. I stood still, watching him warily out of the corner of my eye.

“Put my saddle on Raja. Ain’t no horse I can’t ride. What’s the big deal ’bout him, anyway?”

“It’s the horses’ day off. Besides, only Pedro rides Raja, you know that.”

Ken glared at Chris. “I said tack him up.”

As he put the saddle on, I could tell Chris was worried.

I felt the electricity in the air as the wind picked up, rustling through the bushes lining the stable yard. The sky was greyer than it had been just a few hours ago.

This doesn’t feel right. It feels very wrong.

When Ken and I reached the track, we were alone. My skin tingled as the heavy feeling in the pit of my stomach began to grow. I stopped, whipped my head in the direction of the barns, and whinnied loudly, hoping that one of my friends would respond. I wanted to go back. It was dinnertime and everyone was eating. Annoyed, I jigged sideways and let out an impatient buck. Ken hauled on the reins and jerked me sharply, angrily, in the mouth.

“Whoa!”

I tensed and started to toss my head.

Why is he jerking my mouth? Why is he shouting? What have I done wrong?

As we started to jog, then gallop, Ken took a short hold on the reins and, pulling roughly, leaned his weight heavily against my mouth.

Does he want me to go faster? Why is he nervous?

I didn’t like this at all. He was heavy and tense, not relaxed like Pedro. He made me nervous.

I want him off my back.

I really want him OFF, NOW!

Head down between my knees, I let out a big, athletic buck, then another, twisting, propping and spinning, then dropping my shoulder and scooting sideways. Ken clung on determinedly and snatched me in the mouth again.

“Here!” He growled in a low voice.

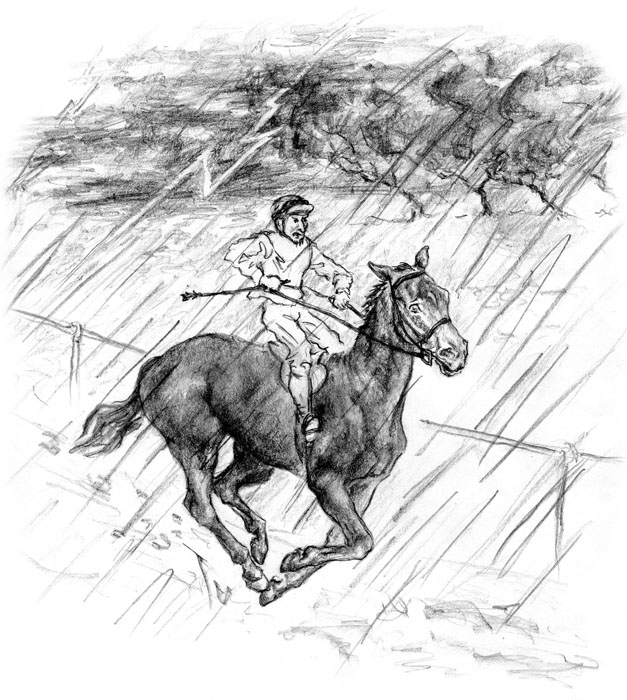

I started galloping, picking up speed, ignoring his rough pulling. I was stronger than he was, of course. As we galloped, heavy raindrops began to fall, accompanied by deep rumbles of thunder. Black clouds hurried across the sky. Suddenly, I heard a loud crack and then saw a yellow streak diving into the slick dirt track.

Lightning!

My heart began to pound and I heard a loud roaring in my ears. I bolted, running as fast as I could, forgetting Ken, forgetting everything but my desire to get away. Through the driving rain, flowers, bushes and trees all a multi-colored blur. Around and around and around the track, through puddles and slippery wet dirt; sucking in gulps of heavy air until, steamy and wet, flanks heaving, I began to tire and pulled up.

Now that I had stopped galloping, I could feel the wetness of the heavy drenched saddle cloth and the slippery leather bridle. I could smell the damp earth, now covered by puddles and streams. Ken savagely yanked me out the gate off the track, jerking the bit roughly in my mouth. I tossed my head angrily and dropped my shoulder.

I spun again but he clung on. I jigged sideways, then slipped, as I stepped on a rake lying in the path. A sharp, burning pain shot up my leg.

Ken cursed, kicked his stirrups free and vaulted off. Still breathing hard, with rain and sweat running down the sides of his face, Ken clutched the thick, wet rubber reins and hit me across the forehead with his whip.

“You piece of garbage, no horse runs away with me! You’re a pig. You need to learn respect. I’m going to teach you a lesson!”

By the time we came back to the barn, the stable hands had gone. Chris walked over to us with a halter in his hand.

“Here. Let me help you take care of Raja.”

“Scram, junior, I’ll take care of him myself. This horse needs to learn some manners.”

“Bob said I was in charge.”

“I mean it. Get out of here. NOW! Before I teach you a lesson, too!” Ken growled. Chris turned and walked away, clenching his fists. Ken put me in my stall, hot and sweaty, without washing me or tending to my cut. After a few hours, I started to shiver. I was burning hot, then freezing cold and my leg throbbed painfully. I was so thirsty. And I was starving! Ken hadn’t given me any water or hay.

Sick and weak, I lay down and drifted into a restless sleep. Terrible dreams came to me: my mother, outlined on the hill, calling to me, “Help me. Run faster.” I started to run but something held me back, like a giant hand. I was unable to move or help her. I tried to whinny to her, but no sound came out. Then the lightning, and Ken, jeering through his brown teeth, “You’re garbage, I’m going to teach you a lesson.”

I woke up while everyone was eating breakfast. I was too weak to get up.

I just want to die.

“Bob, Chris, come quick, Raja’s sick!” Pedro shouted with alarm. I tried to lift my head, then put it down again as the stall started to spin. I was burning up and terribly thirsty and by now my leg was swollen double its normal size. He pinched the skin on my neck. “See how dehydrated he is. Chris, get him some water with electrolytes. Hurry!”

After I had a drink, several long sips at a time, Bob put something under my tail and held it for a few minutes. “One hundred and three degrees.” Bob shook his head, “He’s in shock.”

He gently sponged off my sweat and dried me with soft towels before urging me to my feet and leading me to the wash stall, where he cleaned my cut and ran cold water from a hose on it for a long time before giving me a shot and putting a bandage on.

“Puncture wounds like this are the worst. If you don’t clean ’em out good, infection gets in and the whole leg swells up,” he shook his head grimly.

“It’ll be a few weeks before this heals enough for Raja to train again. We’ll put him on antibiotics right away so the infection doesn’t get worse. Chris, make sure he gets cold-hosed and hand grazed at least four times a day.”

“Yes, boss.” Chris hung his head, dejected. He looked down at his dusty boots, hiding the tears now running down his cheeks. He sniffed.

“Chris, I don’t understand how you let this happen. I’m disappointed in you.”

“I’m so sorry. It won’t happen again.”

“Because you’re young, I’ll give you one more chance, but that’s it. One chance. If ANYTHING like this happens again, I’m afraid we can’t allow you to work with these horses. It’s not just about allowing a nice animal, any animal, to be needlessly hurt, which is bad enough in itself. Do you have any idea how valuable these horses are? Raja, here, is worth millions. I can’t take the risk of something else happening. I told Ken to leave and never set foot on this farm again. Good riddance, I say.” He shook his head in disgust.