But what comes of all of this attention, all the hand-wringing, head-shaking, woe-is-sports? What do we do about it? I certainly do not claim to have magic answers. But I have some ideas. And I have some opinions on some of the ideas I’ve heard from other experts. I am, above all, a skeptic. I put every potential solution to two tests: First, can agents and other people with an agenda find a way around it? Can guys like me beat the system? Does it really improve anything or just put a little cosmetic cover on the acne? And second, is it fair? Does the fix give an unfair edge to one school, or type of school, over another?

I want to preface my discussion of solutions by reiterating that my experiences are limited to football, the only sport I was involved in. From what I understand the world of basketball is littered with behavior that may make football players and football agents look like Boy Scouts. Unlike baseball players, who have the option to pass on college and immediately start their professional careers in the minor leagues, or basketball players, who can be “one and done” (one year of college or at least nineteen years old), using college or overseas ball as a brief stopover on the way to the NBA, football players are in a different, much more restrictive environment. Currently, after high school, it’s either play college football (essentially, the unpaid minor league system of the NFL), or nothing. Athletes can’t declare themselves eligible for the NFL until they are at least three years removed from high school. If they did nothing in that time period, they would lose their skills. No international or minor-league alternative exists. It’s play for a college team or what … play semi-pro? Other than Eric Swann, the defensive tackle drafted by the Arizona Cardinals in 1991, and the occasional former soccer player turned place-kicker, the number of noncollege or semi-pro players in the NFL is as close to zero percent as you can get.

And the system is hard, if not impossible, to challenge. Maurice Clarett, who was arguably the rare talent ready to play in the NFL after his freshman year, fought the rule in court, won, then lost on appeal. No surprise that the billion-dollar enterprise prevailed in the courts, maintaining what I believe to be an oppressive, monopolistic system. Maurice, deprived by that ruling of utilizing his best talents, was left in the cold to survive while sitting out and waiting, He never had good judgment, but he might have succeeded anyway if not for the restrictive draft rules. The undeniable fact is, football players have no alternative available. It’s the NCAA or nothing.

The fixes for college football fall into two basic categories: 1) better policing of the system as it stands and 2) changing the system. Actually, there’s a third category: Ignoring the problem. That’s the route that has been taken to date, with an occasional dash of number one to keep the media and outraged citizens at bay.

Better Policing

Right now, the various regulatory bodies—NCAA, NFLPA, and the individual states—provide rules, and some laws, that are meant to govern behavior. In my opinion, if they were all enforced, we’d still have a huge problem: injustice. Screwing the geese who lay the golden eggs, the so-called student-athletes, aka indentured servants. Players make college football a success. The schools get all the money. The players get nothing. That’s injustice. According to Richard Karcher, professor of sports law at Florida Coastal School of Law, it’s an ideal, if cynical, economic model. An institution gets to make a fortune and doesn’t have to pay its workforce. Zero labor costs (other than scholarships, which the institutions also hand out for academics, need, diversity, and other reasons). How ecstatic would General Motors be with a no-labor-cost model? Or Apple? Or Walmart?

Nonetheless, enforcement today is token at best, and at worst, a total joke. It could be better, much better, and that would decrease the flagrant corruption of supposed amateur athletics. To understand what can be done, you have to look at the issues from the top down, each one interlocking with the next; find the real points of vulnerability; and apply pressure where it matters. Not surprisingly, it’s all about money.

The Uniform Athlete Agent Act

Passed in 2000, the Act requires agents to register in each state that ratifies the law and it allows for criminal and civil penalties to be sought at the state level but enforcement is on a state-by-state basis, with no overarching governing body. Some states are aggressive, some are not. Some prosecutors are zealous, some are not. Registration of agents doesn’t take place in every state. And there is a growing trend to expand the definition of an “agent.” The intention is to restrict more people’s behavior but in fact it confuses the issue of who is and who isn’t an agent. (For further discussion, see page 247, “Runners.”) Each state adopts the act with its own twists and modifications. As of 2010, half of the forty-two states that had enacted Uniform Athlete Agent acts had never issued a single penalty. Oversight and regulation must be federal—federally funded, federally overseen, federally enforced. If it’s a problem worthy of legislation—arguable in itself—then it’s a national problem, not a local or regional one.

SPARTA: Sports Agent Responsibility and Trust Act

SPARTA is a federal law that bars giving false information to a college athlete and providing anything of value to a player or person associated with the player prior to entering into a contract. SPARTA permits states and/or colleges to investigate, but the states are limited in funds and time, and the colleges are not quick to encourage investigations into activities that generate substantial revenue. Federal enforcement would require cooperation from states and colleges. Colleges have no drive to find bad news that results in punishment contrary to their own economic self-interest. To have meaningful enforcement, you have to have economic leverage. Follow the money. Apply pressure to those who stand to gain or lose.

The NCAA

The NCAA has oversight responsibility for college sports but it is composed of, and funded by, the member schools that collectively make the very rules the association is supposed to enforce. It shows favoritism toward some schools over others and it does not encourage schools to look into and correct problems.

Currently, if a school suspects a problem, and under SPARTA, pursues its rights to civil litigation against an offending party (i.e., agent), and during the discovery process uncovers more transgressions than the original, it puts itself in even greater potential jeopardy. The NCAA needs to grant some form of immunity—defining the scope of the issues or the time frame—similar to the way government prosecutors do, that limits the harm the school can do to itself while trying to uncover bad behavior.

If the NCAA wants to be effective in policing behavior (and that’s a big “if”), it should employ its economic leverage with the NFL. The NCAA, via college football, is the de facto minor league of pro football. The NFL depends on a steady flow of outstanding players and therefore stands to gain or lose the most from assuring or interrupting that flow. The threat of turning off the spigot will work. When a handful of college coaches stood up recently and said no to NFL access to practice fields, players, and games, the NFL paid attention, if only briefly. Roger Goodell condemned “bad behavior” that violates NCAA rules and exerted pressure on the NFLPA to, in turn, pressure their members not to break the rules.

And on the rare occasions when the NCAA actually does take action, the punishments must be consistent, not arbitrary, and not favoring one school over another. Why were the Ohio State players suspended for five games but allowed to play in the prestigious Sugar Bowl? Why, in the Reggie Bush incident, was USC deemed to have had a lack of institutional control—a harsh verdict—when UNC, having had coaches aware of and part of violations, was not found to have had the same lack of institutional control?

The NFLPA

The NFLPA licenses, reviews, oversees, and monitors agent behavior but as the players’ union, the NFLPA has no incentive to be more aggressive since its purpose is to bring the best players possible into the professional game and to get them paid as well as possible once they get there.

Again, if the NCAA wants to clean up conduct, they have to apply leverage where they have it: through economic influence on the NFL. If they restrict the NFL’s access to talented marquee players, the league can then put pressure on the NFLPA to police its agents more vigilantly, more evenly—and not just punish a few sacrificial lambs from time to time. The NFL and NFLPA’s combined economic leverage is far more compelling than any moral pressure, and far more efficient than any legal processes.

University Compliance Departments

Universities maintain compliance departments to self-monitor student-athlete conduct, including scholarships, academics, eligibility, personal issues, and other activities. But what they most focus on is educating players about the rules, chapter and verse on the specific regulations, what they can and cannot do. The plain fact is, most if not all the players know the central rule: You cannot accept anything of value. Period. It’s not that complicated. They get it.

But if we delude ourselves into thinking compliance departments can police athlete-agent-booster activity, we’ve already had a case of short-term amnesia on the Nevin Shapiro–University of Miami debauchery—the mansions, yachts, meals, liquor, strippers, parties, plane tickets, jewelry, car rims, hookers, yachts, and lots and lots of cash made available right under the noses of coaches, trainers, and compliance officers.

Between the shortfalls of scholarships, the adulation of fans and the media, the less–than–Boy Scout backgrounds of too many players (see below), and simply the temptation, players break the rules. If the compliance department drums those rules into the players, they can rationalize that they have done their jobs. And even if they want to be vigilant in monitoring and enforcing the rules, the departments are typically small and underfunded and, amazingly, they report to the athletic director and/or the coaches. In other words, they are supposed to police their own bosses.

Sports Illustrated and CBS News jointly investigated 2,837 players on the Sports Illustrated 2010 preseason rosters of the top twenty-five teams. Results: 204 players had criminal records. A total of 277 different offenses ranging from 105 for drugs and alcohol, 75 nuisance crimes, 56 violent crimes, and 41 property crimes. Digging further they found, among a 318-player sample from Florida plus 300 from other areas, 58 of the total arrests were for crimes committed while juveniles. In other words, 7 percent of the best players had criminal records and 21 percent of those were juvenile offenders. Is it a surprise they get in trouble when they get to college? Or that their behavior rubs off on other players? Is it a shock to find the compliance departments aren’t effective?

In cases like Miami, there’s a natural reaction to place the blame squarely on the shoulders of the university’s compliance staff, in this instance, Compliance Director David Reed. Before we make him responsible, though, ask who pays him, who he reports to, who he owes allegiance to—or, put another way, who decides if he has a job or not. It’s the university’s athletic department. And in a big sports school like Miami, the most powerful people in the athletic department are the head coaches of the football and basketball teams. Compliance works for the coaches. Conflict? Uh, yeah.

It’s against the self-interest of the compliance department to find wrongdoing. (If that sounds similar to the criticism of Wall Street compliance departments being paid by Wall Street firms, during the financial meltdown, it’s no coincidence.)

In my nearly twenty-year career, half of which was spent providing illegal benefits, I never once met or saw any compliance personnel. That is, until I was asked to participate in panel discussions at law schools around the country and speak at the NCAA regional rules seminars in front of hundreds of the Division I compliance staffers. They’re invisible … by design. Why didn’t I see them? They’re often housed in the bowels of the athletic department’s building, deep in the interior, with no windows to the practice fields or anywhere near the entrances to weight rooms or locker rooms. They literally don’t see the players or who the players come in contact with. Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil.

Miami’s David Reed is a member, and maybe a victim, of the same unrealistic structure as are all compliance personnel in college sports. One compliance officer I met at the NCAA Tampa Regional Rules Meeting told me when she was interviewed for her job, the head coach asked her, “Do you see your job more as firefighter or policeman?” Clearly the right answer to get and keep the job was “firefighter.” Contain the flames, stop the damage from spreading. But don’t be a cop; cops investigate. Compliance departments, in my cynical view, exist so the university can 1) say they have one, 2) claim to do their job, and 3) have someone to blame when the school is caught doing wrong.

Want a real solution—real change—instead of the next exposé? Don’t blame the compliance departments; change the system. Make them like Eliot Ness’s “Untouchables,” who busted the bootleggers—not local cops on the take, but G-men. Take compliance departments off the local—or school—payroll that can be easily corrupted and put them on an autonomous payroll of the NCAA. And by the way, they should give the compliance departments offices with windows to the practice field. NCAA oversight just might produce more vigilant compliance staffs and an atmosphere more conducive to rules enforcement as opposed to self-preservation.

Then the NCAA should drastically increase the severity of punishment, penalizing from the top down, not just the bottom up. That means the university president. If a school, team, players, or coaches are found to have violated NCAA regulations or state statutes, do not restrict the punishment to the players or coaches or compliance departments. Penalize the university president. Fine him or her on the first infraction. Fire him or her on the second infraction, along with the coach. Period.

One more thing: Offer rewards for whistle-blowers for bringing infractions to light.

Athletic departments will hate this recommendation—it’s a loss of power and an admission of failure—but it’s time that the NCAA member institutions acknowledge that the NCAA enforcement model reliant on self-monitoring by athletic departments has failed. Just ask Nevin Shapiro after his free-rein rampage at Miami. Like me, he never got caught. (If it weren’t for his Ponzi scheme, he might still be flaunting the rules.)

Agent Day

A lot of schools’ compliance departments set up Agent Day at the college. They invite any agent who wants to meet and talk to players, and any players who want to meet agents, to a room full of tables, chairs, notepads, and Gatorade. Each player-agent meeting is for a few minutes, then a buzzer goes off and the player moves to the next agent’s table. It’s speed-dating for agents and players. It’s fair, open, and totally worthless. First, it’s impossible to decide if you click with an agent in five minutes and vice versa. But more importantly, the agents who come aren’t the ones to worry about. It’s the ones who don’t come, who have already made contact with the players, or who will make it on their own, or through a well-placed runner. Agent Day is another way to look like they’re doing the right things—Hey, we invite the agents to meet the players under our supervision, totally transparently—a CYA for the college. My attitude was always, Agent Day is whatever day I can meet with a player.

The Junior Rule

The NCAA has no rules regarding contact between agents and players, only that the players, family, and friends can’t accept anything of value or enter into an agreement without risking their college eligibility.

The Junior Rule, as it’s known, came into being in 2007 at the urging of USC coach Pete Carroll with support from Executive Director of the NFLPA Gene Upshaw. Carroll was incensed over agents and runners pursuing his players in the aftermath of the stories of Reggie Bush receiving improper benefits. The rule prohibited agents from contacting players until January 18, or three days following the deadline to declare for the NFL draft. An unintended consequence was that a player therefore couldn’t get professional input on one of the most important decisions of his career. The rule was changed in 2009 to bar agents or their reps from player contact until the last regular season or conference championship game, or December 1, whichever date is later—not much of an improvement for the players. And instead of curbing the practices of agents, it has fueled the influence of uncertified agents, financial advisors, marketing reps, and runners, for their own benefit and as conduits to certified agents. It gave power to people the NFLPA can’t control. The Junior Rule is still broken. Until authorized agents are allowed contact with players, the rule will be flaunted. Agents will get to players one way or the other. Fix the rule or get rid of it.

Runners

Runners connect agents to players. But runners can no longer be defined in the casual street terms of the past—a friend of a player, teammate, roommate, cousin. Today anyone and everyone may be a runner—mother, father, girlfriend, college booster, financial advisor, minister, personal trainer, reps of high-profile training facilities, high school coach, junior college coach, and big-time college coach—anyone who stands to gain by making the connection. You can’t get most coaches to talk about the problem because they’re in the game. They’re there to win. But once they’re out, it’s a different story. In an ESPNLosAngels.com online feature, former coaches John Robinson of USC and Terry Donahue of UCLA talked about the problem candidly.

By Ramona Shelburne ESPNLosAngeles.com

OCTOBER 14, 2010

ROBINSON AND DONAHUE ADDRESS AGENTS

… Robinson and Donahue wanted to talk. Out loud, openly and honestly. About what has gone on, why it has gone on, and whether there is a solution or compromise.

“I don’t think there’s a coach in the country, unless he’s a liar, that’s going to say, ‘It never happened at my school, my kids wouldn’t do that,’ ” Robinson said. “There’s no way.”

… Robinson said he and his coaching staff were constantly on the lookout for agents’ “runners,” who would approach players after games and practices and offer them money. “Agents would give runners $100 [to give to players] so they could take their girl out for dinner that night,” he said. “They’d shake hands with them, and there’d be a $100 bill folded up. We used to try to identify who the runners are and then threaten ’em.”

It was, of course, a losing battle. All the warnings could go only so far, Robinson said.

Donahue said UCLA coaches and administrators spoke to players often about agents and what benefits they could not accept under NCAA rules. “We talked about it all the time,” Donahue said. “There wasn’t anybody that did anything out of ignorance. Everybody understood what was permitted, what wasn’t permitted. No one acted out of ignorance. I can guarantee you that.”

… Some of the meetings with players were heartbreaking. “That was one of the toughest things for me as a head coach, was the kid who was stressed for whatever reason,” Robinson said. “His girlfriend was pregnant, his parents were this or that, he had a car and couldn’t make the payment. He’d come to me and say, ‘What do I do, Coach?’ You were stuck. The only thing you could do is try to get him a job on the weekends or in the offseason. But then they made it so you couldn’t do that.

“Every coach who has ever coached has had a kid in his office that says, ‘Coach, I’m dying here,’ and you wind up giving him 100 bucks or letting him use your phone. I used to have a kid that would come into my office and he was so homesick that he’d start crying. I would dial his mom on the phone and he talked to her for 10 minutes and he’d say, ‘Oh, I’m OK now.’

“Well, that was a violation. But hell, I didn’t have any other solution.”

Ironically, maybe the most influential of all of the “runners” is the college coach.

In the midst of another round of investigations into agent violations in the SEC, Nick Saban, the Alabama head coach, said, “The agents that do this—and I hate to say this, but how are they any better than a pimp?” But Saban, like other big-time college coaches, has his own agent and that agent will have unique access to his players. That agent can be in the coach’s office, in the locker room, on the field. The players see him, meet him, and see that the coach, often the most important authority figure in their lives, has given that agent his tacit stamp of approval.

Nick Saban’s agent is Jimmy Sexton, who also happens to represent high-profile college coaches Steve Spurrier (University of South Carolina), Houston Nutt (Ole Miss), and Tommy Tuberville (Texas Tech). According to an online article from Birmingham News writer Kevin Scarbinsky, “Sexton said he avoids talking to their players when he stops by practice to talk to Tuberville or Saban. And although he says representing a coach gives him “a good entrée to the player,” he balks at the notion that a coach “can hand-deliver you players.” Tuberville commented on Sexton pursuing players, “I tell him, ‘You can go after any guys we have. (But) you’re on your own unless they ask me.’ ” Oh, unless they ask him? Well, thank goodness, no problems there.

Players ask their coaches everything. How to run pass patterns, which workouts to do, if they can get more playing time, what it takes to get into the NFL, what to eat, how much to sleep, whether they can go home for the weekend, what time the team plane leaves. So, when it comes to a life decision like picking an agent, you think the player and coach won’t talk? And that coach decides if and when the player plays, determines how much national exposure he’ll get, and even comments to the media about his play after the game. Do you think the player wants to go against what his coach thinks is best? Let me answer all those questions with another question: Is it a coincidence that so many players at a given school happen to sign with the same agent or other agents at the same agency as their coach? At the Arizona NCAA meeting, I asked compliance people if they knew who their coach’s agent was. Most had never thought to find out.

If, as Nick Saban says, agents are no better than pimps, let’s play out the analogy. What does that make the players and the coaches? Who are the johns and the hookers? Who’s getting screwed and who’s doing the screwing? I see a lot of hypocrisy and finger-pointing.

The obvious solution is that agents who represent coaches should not be allowed to represent players currently on the same team.

There is another twist to the attempts to crack down on runners of all types. Many state governments, as well as athletic governing bodies, are broadening the definition of “agent” to include runners, recruiters, financial advisors, brand managers, family, friends, and anyone who makes contact with a player for potential gain. The intention of this change is basically good. But the execution is flawed. Plenty of players who are supposedly taught the rules by their compliance departments will have trouble accepting the counterintuitive notion that a college booster is an agent, a roommate is an agent, a street runner is an agent, or a friend from the old neighborhood is an agent. Hey, I’m not an agent. I’m a fan. Class of eighty-nine! Players may understand they can’t take money from an agent, but why can’t they take something from an alum, or their cousin? The real solution would be to have two clear-cut legal definitions: 1) Agent: A person who has been certified by the NFLPA, credentialed, vetted, and approved. 2) Runners/Recruiters: Anyone who approaches a player for the purpose of establishing a relationship for gain or connecting a player to someone for gain. Without that clear definition and explanation, players have the excuse of not understanding, the excuse to give in to temptation, and there is the possibility of unintended consequences.

Go back to the case of Willie Lyles, the former scout accused of taking $25,000 in exchange for information. Willie and I had an interesting conversation about the possible injustices that could result from a broadened definition of agent status. Remember, it was Willie who went public with his story, not someone else. Under a definition broadened to include runners, trainers, scouts, advisors, et alia, Willie’s actions could be construed as the actions of an “agent,” making him vulnerable to criminal prosecution. But he’s not an agent, and he shouldn’t be prosecuted like one. Not wanting to incriminate himself, he may not provide that information, thereby inadvertently letting University of Oregon, its coach Chip Kelly, and other athletic department personnel off the hook.

Define agents and define runners and enforce the rules on both.

Getting to Players

So how do agents get to players with the Uniform Athlete Agent Act, SPARTA, compliance departments, and coaches trying to limit access? Easily.

First of all, this supposedly protective body—the team itself—brands its players like cattle. You don’t have to know what the star running back looks like. You just have to know his jersey number. And since he’s a star, constantly on TV, you know. Number 22. Then you hang out near the athletic facilities or the practice field. Pretty soon a guy will walk up carrying a school-issued backpack with “22” stenciled on it. If you miss the backpack, he may be wearing sweats or shorts with the same “22” on them. As responsible parents today, we’re told not to send our kids to school with their names on their clothes or book bags because it makes it easier for predators to act like they know them. Predators around schoolkids are scary but, fortunately, uncommon. The type of predators who go after college athletes might not be quite as frightening but they’re everywhere—anyone and everyone who wants a piece of the athlete. Yet colleges label the players they’re trying to protect so agents can find them, talk to them, buy them lunch, and even give them cash. It doesn’t take a genius to fix that problem.

Then there’s social networking—almost universal access—notably on Facebook and Twitter. That access is a lot harder to control. And thanks to “ghosting,” even people who don’t exist can get to almost anyone they want. Ghosting is a form of identity theft, or identity invention, whereby someone creates a name, background, and seemingly real person and uses that new personality to contact other people. Scam artists use it to try to get credit card and other financial information, for sexual contact, or just for harassment. For sports agents, it’s like a key to a player’s front door. If you want to learn all about a player, just create an identity for a sexy-looking girl, paste in some hot photos you can easily find on the Internet, and then “friend” the player. Chances are he’ll accept your friend request, and then you can go to his Facebook page and see his profile, photos, friend list, info, and start exchanging messages, pokes, even texts. The “you” that’s been created doesn’t even exist. But by the time that agent gets to campus, he knows everything there is to know about the player: where he hangs out, where he parties, who his friends are, his girlfriends, what kind of car he drives, the movies and music he likes, and lots of pictures so you know exactly what he looks like, with or without his jersey number. Social networking is like a GPS for an agent. It’s the modern version of “find the fat chick.”

The NCAA, through officers like, Director of Agent, Gambling and Amateurism Activities Rachel Newman Baker, recognizes the problem but faces issues of free speech in efforts to control it. However, it would be possible for all players to agree that their college’s or university’s compliance department would have access as a “friend” to their Facebook page so that all communications were at least visible.

This is a nice little list of fixes: federal enforcement of agent laws, NCAA pressure on the NFL and NFLPA, independent compliance departments not employed by colleges, restrictions on agents from representing both coaches and players at the same school, changing the Junior Rule, not issuing paraphernalia with player numbers, and monitoring social networking. Each may be effective at reducing certain types of infractions. But they are Band-Aids, not treatments for the disease. At best, they will modify behavior but not change it. There’s an old expression that the definition of insanity is when you do the same thing over and over but expect different results. That’s what we’ve done with college sports. If we want different results, we have to change the system.

Changing the System

To turn the old phrase around, if it’s broke, fix it. Stop patching it, face reality, and make real changes. Emancipate the athlete. Recognize the real value of the players in the economic model—the business—of college football; recognize that there would be no college football without star quarterbacks and wide receivers and blitzing linebackers, and reward the stars. Pay the players. The question is how.

Realistic Scholarships

The 2009 study by Ithaca College and the National College Players Association found that a typical “full-ride” scholarship for a Division I athlete actually left a shortfall. On average, student-athlete expenses, meaning tuition plus room and board, exceed the amount of the average scholarship by $2,951. With the schedule they keep in order to perform at the highest level in sports, how are the players supposed to get that money? Many cannot turn to their families. They’re restricted from working during the school year, and, in any case, they wouldn’t have time between workouts, games, and classes to hold down even a part-time job. So, they either live at a subsistence level or they find other ways, such as taking money from agents. I typically loaned guys $300 to $1,500 per month. Most of the loans we made would have filled the shortfall of the Ithaca study (not that that was my motivation; I just wanted to sign the players). There was simply a need and we conveniently filled it. If an athlete is getting a “full scholarship,” it should be full, not partial. Pell Grants and other programs that players could be taking advantage of are often not explained in easily understood terms and anyone who’s ever tried to fill out an application for a grant or student loan knows it’s not easy to navigate. There are some who argue that the amounts players receive is enough. But the player’s perception is reality. If he perceives that the need exists, it exists and he will try to fill it. There is no question that if the shortfall were removed, some of the violations would be eliminated.

Of course, plenty of players who take money from agents or boosters aren’t doing it just to cover expenses. Some do it out of greed, or just because it’s there for the taking. Increasing to true full scholarships will not be a deterrent. The greedy will always be willing to take the risk of being caught regardless of the consequences. Harsher penalties may slow them down, but they won’t stop them.

South Carolina coach Steve Spurrier even got a group of other top coaches to propose they pay players $300 a game, out of their own pockets, to supplement players’ finances. But frankly, it’s a headline-making but impractical gesture. How many coaches could do it? How many would? Would the coach really pay, or would the school? Is it fair from coach to coach and school to school? And aren’t coaches being paid way too much if they can offer to pay every player on their team?

What About the Value of Education?

So, if you give true full rides, the athlete covers his expenses and gets a college education, right? Oh sure. The college football purists’ argument that the players are getting paid in the form of an education is almost laughable. The concept may be logical but it simply is not realistic. I didn’t need the experience of preparing players for the Wonderlic test to show that they may have received a degree (though more than 50 percent of the players don’t graduate), but clearly they did not get the education promised them. I could see it and hear it in every conversation. Too many players came into college uneducated and left the same way. Between player-friendly professors and “rogue tutors” (as in the UNC case), these institutions of higher learning too often fail to live up to their end of the bargain. The player’s academic schedule is usually built around the team schedule, a clear signal of priorities. Classes and study are to be fit in between practices, film study, workouts, team meetings, and anything else that affects on-the-field performance. School doesn’t come first. Or even second. For most players, it’s way down the list, if it’s on the list at all.

Share the Wealth

Big-time college sports programs make a lot of money from the sale of jerseys, shorts, hats, you name it, with the school name and the number of star players emblazoned on them. Reggie Bush made the number 5 jersey a top seller for USC. Cam Newton’s number 2 moved a lot of memorabilia for Auburn. Ohio State, Notre Dame, Texas, Michigan, Penn State, Miami, LSU, Oklahoma, Alabama, and others make a small fortune every year literally off the backs of their players. And the players who make those numbers famous get nothing. Why not give those star players a piece of every sale? You can argue that the support players, the linemen who protect Cam Newton or make a hole for Reggie Bush, are unsung heroes. But it’s the same way in the NFL, and anyway, that’s no reason to cut star players out of the revenue for their own accomplishments. The real problem is, only a handful of players are stars whose numbers sell. And the others still need to be treated fairly … or they remain vulnerable to money from other sources.

How About Total Revenue?

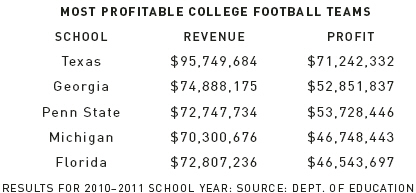

According to CNNMoney.com in 2010, the total take of the richest college football programs was over $1 billion, including all sources of income from tickets to jerseys to television broadcast rights. (The chart below highlights some of those programs.)

Why not share the college’s total revenue with the players? Give the team a predetermined percentage of all income, with bonuses for championships and bowl games and being named to All-America teams. Let the teams divide it up among the players based on playing time, stats, or reaching individual goals. Or let them pay everyone the same amount. But let the players who are bringing in the money share the money.

If college is the minor league of the NFL, then pay the minor league players just like baseball does. It would certainly be more fair than the current system. But it’s flawed, highly flawed. First, it tilts in favor of those schools that can draw big audiences. Notre Dame gets viewers whether they win or lose. Plenty of very good teams don’t. So, if they pay players based on what they take in, some schools will be able to pay more and get more good players. Sort of like the Yankees in baseball.

But the biggest reason it won’t work is the colleges won’t let it work. They consider this money theirs. They’re used to getting it. Why would they be willing to give up even a portion of it? Unless all the college prospects in America decide to go on strike, they’re not getting a share of college football dollars.

An Idea That Just Might Work

Agent Loans

Agents advance money to players now. It’s against the rules but it keeps happening, whether for need or greed or both. Why not do it aboveboard? With total transparency? Set up oversight and regulation. Establish interest rates, at or below market value. Provide standardized forms and loan agreements. Create a fair market system.

Here’s how it could work:

1. Any certified agent who wishes to participate could register to lend money to athletes.

2. Interest rates would be set at or below market rates and published.

3. The agent and player would be allowed to meet openly and freely to discuss the amounts, terms, and details. The Junior Rule would be abolished to allow for this. (As an NCAA-sanctioned program, it would prevent underage or high school kids from participation, plus investing in very young players is at best a long shot considering how greatly abilities change during those years.) Once agent and player arrive at an agreement, they would meet regularly, which would enable the agent to parcel out the funds on a piecemeal basis, rather than in a lump sum, and therefore simultaneously establish an ongoing relationship with the player.

4. The agent and the marketplace would determine how much it would make sense to lend. If agent X determines that player Y is worth $10,000 a year—that is, that the player will earn enough once signed to a pro contract to repay that amount—then the agent can lend $10,000. If agent Z determines the player is worth more, say $15,000, then he can take the risk, like any lender, that the player will pay back more. It would truly be a free-market system.

5. Notices of agent-player agreements would be posted in locker rooms to end or minimize locker-room runners from wooing players for agents. Everyone would know who each player was working with.

6. The transaction would be a true business deal, a loan. The player would owe the money to the agent. If and when the player signed a pro deal, he would begin to repay the money on pre-agreed terms. It would protect all of the parties in the transaction.

7. If the player’s career did not pan out, if he were not drafted or signed, then the agent would have made a bad investment without recourse.

8. A player could openly switch agents if or when he determined that another agent offered him a better deal, or would simply be a better fit. Again, it would be the agent’s choice, based on his assessment of market value, whether to lend more or less. And the new agent would assume the liability for the loans from the previous agent. Postings would be made of the switch.

9. The NCAA would retain paperwork on all transactions. And the NCAA would have access to agent phone and bank records, which they do not currently have, in order to track activities, movement of money, etc. This would allow for the equivalent of subpoena power for any requested documents; otherwise an agent would be immediately removed from participation in the loan program.

10. This would remove the NFLPA from all agent oversight other than certification of agents.

11. This system would be totally consistent with Title IX, often a stumbling block for new college sports legislation. Rather than favoring only the top sports, it could fuel any or all sports. If an agent determined that a soccer player could earn substantial money in the marketplace, he would be free to lend money to the soccer player. Or the hockey player. Or swimmer. Male and female athletes alike.

Agent loans would be a totally transparent program with advantages over the current system, or nonsystem. The process would be out in the open, under the scrutiny of anyone who wanted to see it, instead of being done clandestinely, in dark bars, or at parties, or through street runners. It would provide for payback of the money. It would not be a gift or a pay-off, but a business deal. The player would agree to take the money, pay the money back, and work with that agent when he declared for the draft. The money could be given in varying amounts dependent upon the need and status of the individual players. Market value would determine what a player could borrow. Market value can change as the player’s performance and his ability to pay back changes when he turns pro. The agent would be taking the risk. The model does not provide one school an advantage in recruiting over another. It rewards the players. And players don’t have to take money from questionable people. In fact, under this system, why would they take money from unsavory characters? Everyone would know who is lending and who is borrowing.

Why would the colleges go for it? Well, for one thing, there is already precedent for it. Players can now borrow against future earnings to buy disability insurance while playing in college. But most importantly, this new system of loans wouldn’t cost the colleges a dime. The money involved would be separate from the revenue the schools now take in from the sale of seats, jerseys, and bowl-game TV rights and adamantly do not want to give up or share. This would be the agents’ money.

Will it happen? Doubtful in the short run. Some may view it as taking money from the bad guys. In fact, it’s a dose of reality. It’s already going on. But instead of doing it in the shadows, this would do it openly, legitimately, with a system, rules, and oversight. It could work. And what we have now does not work. That’s one thing everyone can agree on.