AFTERWORD

Theodore Roosevelt was what we today call a “Renaissance Man.” He certainly was more so than any president, including Jefferson, and is perhaps unique among all Americans in our history. Yet his uniqueness can elude us. For Lincoln, highly revered by TR for his very nature, not just his attainments, and for TR's fifth cousin Franklin D. Roosevelt, the presidency was the pinnacle of their careers. For Theodore Roosevelt, however, as great a president as he was (and he finally has been ensconced as a “great” by general consensus and numerous polls of historians), the presidency was only one aspect of his life, one detail of his biography.

Another unique aspect of TR eludes us. Many of history's “Renaissance” figures—those of multiple achievements and broad visions—tend to be defined by their field, or several fields, of specialty. But Theodore Roosevelt would have agreed with Edwin Marcus's cartoon. He was an American first, an American last, proudest to be called “American.” We can think of history's other polymaths who are known by their fields of expertise but not, primarily, their citizenship. Indeed we may find some exceptions in history, but none would be more assertive about identifying with his or her nation than Theodore Roosevelt was. To him, “American” was the noblest description he could claim.

“American” was not a cheap title to TR, nor a red-white-and-blue chip on his shoulder. Americanism was a work in progress, not to be relied upon for automatic glory. Being an American meant something special; and like anything special, it was worth fighting for. He believed it needed to be defended, periodically won, and, inevitably, reformed. Elihu Root, who variously was an ally and opponent of TR, said,

Review the roster of the few great men of history, our own history, the history of the world; and when you have finished the review, you will find that Theodore Roosevelt was the greatest teacher of the essentials of popular self-government the world has ever known.…The future of our country will depend upon having men, real men of sincerity and truth, of unshakable conviction, of power, of personality, with the spirit of Justice and the fighting spirit through all the generations; and the mightiest service that can be seen today to accomplish that for our country is to make it impossible that Theodore Roosevelt, his teaching and his personality shall be forgotten. Oh, that we might have him with us now!

We have seen in this book how TR, drawing upon values inculcated by his father, believed that he knew what was right for America, and proceeded to act. This was not paternalism, it was conviction. Some opponents, including a few cartoonists, ascribed it to egoism. Liberals occasionally regret that TR seemed to act unilaterally in foreign affairs. Conservatives sometimes regret that the era of the strong chief executive commenced with him. But Roosevelt's motivation was the desire for a better America, a stronger America, a fairer America, where every person could rise, or fall, according to high standards of merit, struggle, and independence.

To Roosevelt the sincere patriot, these were not clichés…and they surely were not givens. He knew that despite the glorious foundations of the republic, America's future could be that of a dystopia: utopia was neither inevitable, nor, if we were to come close to it, permanent. With American citizenship as in life itself, the process honors the goal. Roosevelt was not a latter-day Cato, calling out that some Carthage must be destroyed; rather, he urged that a new America must be built up. Reform, the watchword of Roo-sevelt's career, was not the slogan of a public scold, but an encouragement to improve things, to always seek a better life for the next generation.

As TR himself expressed it,

It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself for a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.

A crayon sketch of the iconic Teddy Bear by the cartoonist who created him, Clifford K. Berryman. Reproduced from the original artwork.

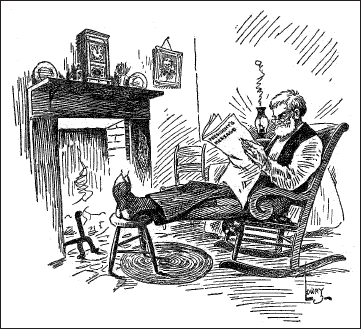

“There was one cartoon made while I was President, in which I appeared incidentally, that was always a great favorite of mine. It pictured an old fellow with chin whiskers, a farmer, in his shirt-sleeves, with his boots off, sitting before the fire, reading the President's Message. On his feet were stockings of the kind I have seen hung up by the dozen in Joe Ferris's store at Medora, in the days when I used to come in to town and sleep in one of the rooms over the store. The title of the picture was “His Favorite Author.” This was the old fellow whom I always used to keep in my mind. He had probably been in the Civil War in his youth; he had worked hard ever since he left the army; he had been a good husband and father; he had brought up his boys and girls to work; he did not wish to do injustice to any one else, but he wanted justice done to himself and to others like him; and I was bound to secure that justice for him if it lay in my power to do so.” cartoon by Everett E. Lowry, The Chicago Chronicle.

TR inspired a generation. His inspiration extended to other lands, virtually to anyone who heard about him. He inspires people yet today, in ways that other leaders have not and cannot. He taught the essentials of popular self-government, as Root said, but others have also done so. A democratic republic, as America was designed to be, is simply not a perpetual-motion machine. Even during his lifetime, TR found himself temporarily dismissed by the nation he usually inspired.

The United States needs a Theodore Roosevelt to remind it periodically of its credo, its goals, and its potential. It needs not the visionary babble of cheery politicians, but the stern encouragement and, if needed, chastisement of visionary leaders. If such high ideals will not arise every generation from the masses, thank God that, occasionally, unique individuals arise to rekindle those ideals in our souls. However, waiting for civic prophets, if not political saviors, is a risky routine. If the American public fails to remember the words of a Theodore Roosevelt and to return to the foundational truths he reaffirmed, the Republic is endangered. TR, like Washington and Lincoln before him, set the bar high for American citizens—but not too high.

A hundred years after the Most Interesting American bounded joyously across his beloved landscape, it is unclear whether Americans will show ourselves worthy of his confidence—confidence shared by our wise Founders, and imparted by God Almighty whose biblical frameworks and whose grace inspired them. It is up to us. Theodore Roosevelt did all he could do—we see it in these pages, observed in myriad ways by observers who were unique themselves. Seeing his life as his contemporaries saw it, we can understand it better and thus strive to live up to his high, American ideals.

Without realizing that it might be his own “I Have a Dream” speech, TR delivered words in early 1912 about the sacrificial fight he took up in the Progressive campaign. This speech was widely quoted six months later, when he was shot in the chest and demanded to be taken to the auditorium anyway, to deliver a speech that night. But we can read those words again as his valedictory; his message to American posterity; and his advice for every citizen amongst us:

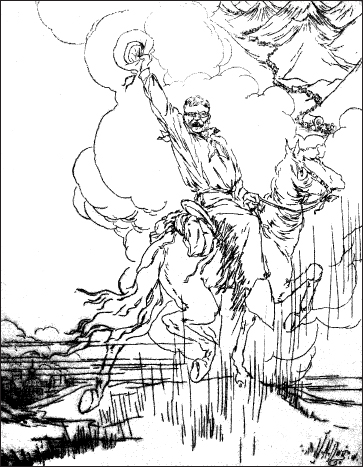

The great “Ding” Darling, a friend of Roosevelt who was also a hunter and conservationist, had a short deadline when he heard the news of TR's death. He quickly sketched a drawing of a ghostly rider, borrowing from the cartoon he had done two years earlier when Buffalo Bill Cody died. He intended to draw a more substantial cartoon for later editions of The Des Moines Register and Tribune, but he never had to. “The Long, Long Trail” became one the most famous American editorial cartoons in history. Ding's cartoon graced walls of innumerable schoolrooms and homes. He made a limited-edition etching (above) in response to many requests.

In order to succeed we need leaders of inspired idealism, leaders to whom are granted great visions, who dream greatly and strive to make their dreams come true; who can kindle the people with the fire from their own burning souls. The leader for the time being, whoever he may be, is but an instrument, to be used until broken and then to be cast aside; and if he is worth his salt he will care no more when he is broken than a soldier cares when he is sent where his life is forfeit in order that the victory may be won. In the long fight for righteousness, the watchword for all of us is spend and be spent. It is of little matter whether any one man fails or succeeds, but the cause shall not fail, for it is the cause of mankind.