“THE BEST MAN I EVER KNEW”

TR was a world away from New York City at Harvard, and he was busy. His courses seemed comparatively easy to him, and, having decided against training to be a naturalist, he chose courses already within the orbit of his interests. Still, campus activities, his clubs, a budding romance, weekend balls and dinners, and hunting trips in Maine all commanded his attention.

Amidst his activities, TR maintained close contact with his family. His father's involvement in national politics would begin suddenly and end quickly, so Theodore, safe at Harvard, scarcely experienced it. Nonetheless, the difficulties his father suffered in his political career were momentous and traumatic, and they left their mark on his son. The episode surely inspired the crusading spirit in TR that lasted a lifetime: a zeal for political reform.

The Reconstruction era, at least in the North, brought prosperity, expansion, and innovation, but it had a dark substratum. Political corruption, while not new in the United States, suddenly spread like an aggressive, noxious weed. Its handmaidens were decadence, exploitation, and a rapid, troubling division between social classes. Periodic press exposures and efforts by reformers ultimately were ineffective in the face of the corruption and collusion of the power elites. Mark Twain criticized the era in his aptly titled The Gilded Age. Henry Adams (writing as the long-secret “Anonymous”) wrote Democracy, a popular satire that certainly created a buzz, though it ignited no reforms.

In New York City, the Democrat “Tweed Ring” of Tammany Hall, engineers of spectacular civic thievery, had been thrown out of power in the municipal elections of 1871, largely due to the powerful cartoons of Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly. But within a few years, Tammany was back in control of the New York City government.

On the national field, Democrat Samuel J. Tilden outpolled Republican Rutherford B. Hayes for the presidency in popular votes in 1876. He seemed to have won the electoral vote, too, but questions arose about the counts in two southern states (where the Republican national administration had maintained a virtual military occupation since the Civil War's end). After weeks of uncertainty, disputed vote-counts in various jurisdictions, and action by the House of Representatives, Hayes was finally certified. Democrats rightfully felt their victory had been stolen, but Tilden discouraged protests (perhaps due to charges that he had attempted subterfuge himself, through cipher telegrams). As part of a silent “deal” between political bosses of the two national parties, federal troops were soon withdrawn from the South, which remained solidly Democrat, while the GOP retained the White House. Unbelievably, the protracted, sordid spectacle of the bazaar-haggling presidential election did not spark major flames of reform throughout the land, either. Politicos just kept rolling along.

The recently inaugurated President Hayes (widely referred to as “His Fraudulency” and “Rutherfraud” B. Hayes) was chastened by the manner of his election, which had been totally managed by GOP bosses. As his wife Lucy reformed the White House social regime (banning wine and liquor from state functions), the new president advocated for civil-service reforms. This obliged him to lock horns with some of his own party's dirtiest scoundrels. Not particularly clever or forceful, Hayes's attempts at reform were doomed to failure. Some of his allies, like Senator James G. Blaine, the focus of many corruption allegations, were hardly spotless themselves. Hayes planned to challenge the boss of the U.S. Senate, New York Republican Roscoe Conkling, and proceed from there to reform the Republican party and the country in general. But Conkling was a formidable foe. The American political landscape was littered with the corpses of many who had tried to take him down.

Senatorial courtesy—respecting the prerogatives of matters, even federal offices, in a senator's home state—was sacrosanct within the upper chamber, so Hayes's frontal assault on Conkling was a dubious enterprise from the start. The president requested the resignation of a Conkling henchman, Chester Alan Arthur, from his post as Collector of the New York Customs House. The Collector was paid $50,000 a year, a salary equal to the president's, the equivalent of $1 million in today's dollars. The Collector was also in a position to receive many kickbacks from arriving imports as well as from a bloated staff—kickbacks for himself, and for the party in power.

In late 1877, Hayes nominated a man of spotless reputation and national respect to replace Arthur as Collector: the philanthropist Theodore Roosevelt. No one could say anything ill of the man, except that he was not subservient to Conkling or his party faction, known as “Stalwarts.” Roosevelt himself, surprised and flattered by the nomination, was willing to assume the Custom House duties and its challenges, not for the salary but for the opportunity to make a major contribution to his nation, to purify his party, and to help lead the reform movement.

Roosevelt had no idea what he would be up against. Arthur refused to resign; the president would not back down, and the stand-off attracted national attention. Democrats and anti-administration Republicans were happy to defend Arthur and to vilify Roosevelt. Rumors were invented, innuendos spread, and all sorts of criticism was aimed at the noble nominee. Roosevelt frankly was bewildered and hurt by the whole affair. It was all begun and ended in the space of a few short weeks. Chester Alan Arthur remained in office. Theodore Roosevelt, the spotless paragon of civic virtue and reform, remained on the playing field, a tattered political leftover.

TR, beginning his sophomore year at Harvard, was aware of the firestorm, but he did not immediately suffer the full force of the blow to his family. He congratulated his father upon the nomination, proud that the man was willing to sacrifice so much to become a crusader for civil-service reform. When he became aware of the campaign of vilification against his father, TR wrote letters of encouragement and sympathy to him—but often only one line. It was certainly not that he didn't care; but apparently he assumed the imbroglio was not as horrible as it, in fact, was. The family in New York was wounded because their honorable paterfamilias had been dishonored. Even at best, the elder Roosevelt found himself talked about as a man who had allowed himself to be a naïve pawn in tawdry political wars.

Shortly after this traumatic episode, the family was blindsided by a calamity worse than the first. Thee's health began to unravel; he suffered acutely, was unable to eat or sleep, and lost weight. Naturally the family attributed the malaise to the strain of the political humiliation. Soon, however, as the pain became excruciating, doctors discovered that he had virulent and inoperable stomach cancer. The cancer advanced rapidly. Theodore's faculties slowly disappeared. He became fevered and delirious, and evinced such pain that doctors could scarcely medicate with effect.

The family decided, at first, not to alarm TR at Harvard beyond general reports of

his father's indisposition. But the sickroom situation deteriorated so rapidly that when

the son was at last advised to rush home to see his father one last time, he arrived hours after his father's death on February 9, 1878. Theodore Roosevelt Senior was just forty-six years old.

The “best friend I ever had,” as TR considered his father, was gone, and TR was stunned beyond consolation, filling his diaries with descriptions of his sorrow, and a gloomy conviction that he could not ever rise to the level of his father as a member of society, as a reformer, or as a man. TR acknowledged the comfort of knowing that his father was in the arms of God, but the comfort belonged more to the elder Roosevelt (released from the ravages of his disease) than to TR himself, bereft of his father and friend. He would feel the loss of his father's advice and guidance bitterly, and he repeatedly swore to live up to his father's ideals, to do what his father would have him do. “But I shall always live my life as he would want…that anything I do would make him proud of me,”

TR declared to family and friends.

TR literally owed his life to his father, who had carried the asthmatic boy in his arms at night, and walked and sleighed through the New York snows, hoping that cold, clear air would open the boy's lungs. He had built his son a state-of-the-art gymnasium and helped him exercise, hired boxing coaches, and taken him on hiking and hunting trips to the Adirondacks. Through it all, he imparted advice and counsel, extolling heroes from the Bible and world history, and providing a real-life example of compassion towards his fellow men. For the rest of his life, TR would meet people who had been helped by his father, in secret episodes never publicized. For instance, when TR was governor, he met John Green Brady, governor of the Alaska Territory, who told him how the elder Roosevelt had given him money when he was a homeless child in New York City, and sent him West to be reared. This was just one of many such stories about his father's generosity shared with TR throughout his adult life.

But in that 1878 winter, the heartbroken young man confided to his diary: “I feel that if it were not for the certainty that he is not dead but gone before, I should almost perish.” He went on, “How little use I am or ever shall be.”

But life went on; it had to go on—and pressing ahead with the Great Adventure, of which life and death are both parts, is what TR's father himself would have counseled.

1877–1878: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

AMERICAN CARTOON JOURNALS

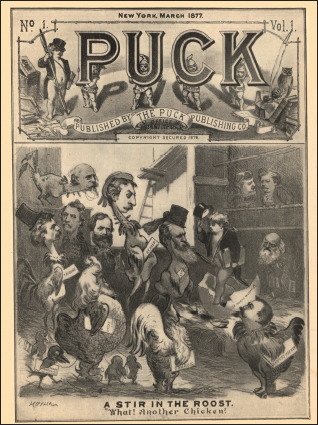

Joseph Keppler was born in Vienna and had a passion for the stage and cartooning. He drew for humor magazines in Vienna and, after emigrating to the United States, in St. Louis. When he started Puck as a German-language cartoon, humor, and political magazine in New York in 1876, he was already a celebrity in the artistic world. He was Leslie's chief cartoonist for a short time, which meant that he was Thomas Nast's major rival. When Puck scored a success (partly on Keppler's innovation—front-page, back-page, and center-spread cartoons in colors), it produced an English-language edition starting in March 1877, and Keppler was thereafter the preeminent American cartoonist. In Keppler's cover of the first issue, the figure of Puck modestly appears among rival magazine and newspaper editors, with the caricature of Thomas Nast in the lower right.

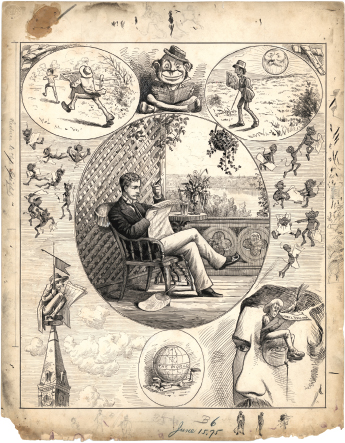

LEFT: The legendary illustrator and cartoonist Arthur Burdett Frost drew this encomium of his paper, The Graphic, in 1875. In the middle is a “typical” Graphic reader, urbane and comfortable. Rival newspapers and their readers are depicted via visual puns—The Sun, The World, etc. Reproduced from the original artwork. Frost's sketches and doodles can be seen in the margins, the formative working of a great artist: among Frost's many later credits were illustrations for Lewis Carroll books and Uncle Remus stories, as well as Theodore Roosevelt's hunting articles.

RIGHT: New York's Daily Graphic was the first American daily newspaper to run illustrations, and lots of them. It was a splashy sensation in the world of journalism, and was aided by the development of mechanical photo-engraving, although, ironically, many of its artists endeavored to make their drawings look like woodcuts. Great cartoonsists like A. B. Frost and E. W. Kemble did some of their first work as cartoonists on the staff. This early issue, from its first month (March of 1873) shows newsboys rushing to hit the streets with the latest edition of the Graphic.

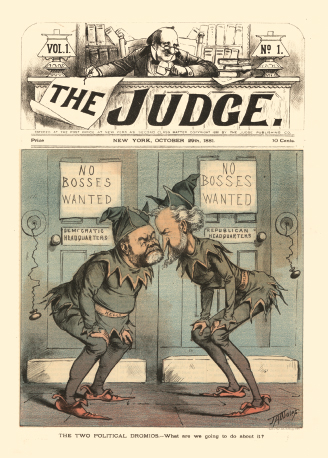

The Judge (later Judge) was an obvious imitation of Puck. Its chief cartoonist was James Albert Wales, a renegade Puck staffer. Other cartoonists were Grant Hamilton (who remained for years and became art editor), Frank Beard, and Thomas Worth, veteran of countless Currier and Ives comic lithographs. After the 1884 campaign, when the political establishment saw how effective Puck was, Republican investors bought Judge, made it a partisan voice, and lured Bernard Gillam and Eugene Zimmerman away from the former publication. Judge was a prominent cartoon magazine into the 1930s, and then limped along under various managements until the early 1950s.

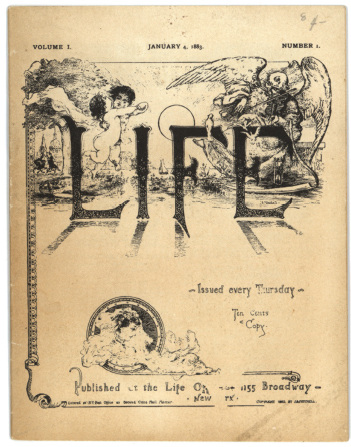

Life was founded by John Ames Mitchell and Edward Sanford Martin, two Harvard grads who had worked on the first issues of the Lampoon there. It launched in 1883 as a black-and-white alternative to Puck—a society journal reminiscent of the English Punch. When cartoonist Charles Dana Gibson introduced the Gibson Girl to its pages, Life's success was assured. The magazine was generally Democratic (founding the Fresh Air Fund for urban children and crusading against vivisection) and rather anti-Semitic. In 1936 the title was bought by Henry Luce of Time in order to launch the photo/news weekly.

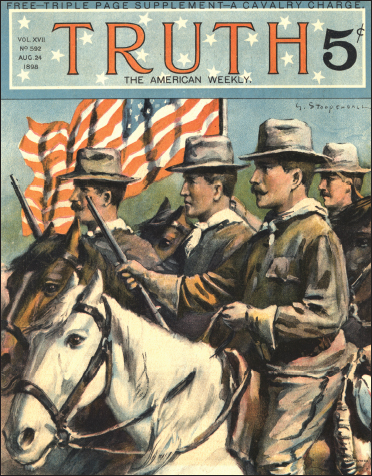

Truth magazine was always a runner-up to Puck and Judge. It was usually designed for what was called the “barber shop readership,” featuring mildly racy cartoons of chorus girls and the like. However, through the years it fluctuated, going heavy or light on politics, featuring high-gloss chromolithographs, and careening between slum cartoons, chorus-girl titillation, and patriotic splashes. Mostly, it is remembered as a breeding-ground for cartoonists who went on to fame in larger venues.

The Verdict was a short-lived color cartoon weekly of the late 1890s (like Vim and The Bee). Its chief cartoonists were MIRS and Horace Taylor. It was edited by Alfred Henry Lewis, a novelist and muckraker in the making; and its publisher was Oliver H. P. Belmont, who would long be active in Democrat politics.

1877–1878: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE TRAUMATIC POLITICAL EXPERIENCE OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT'S FATHER

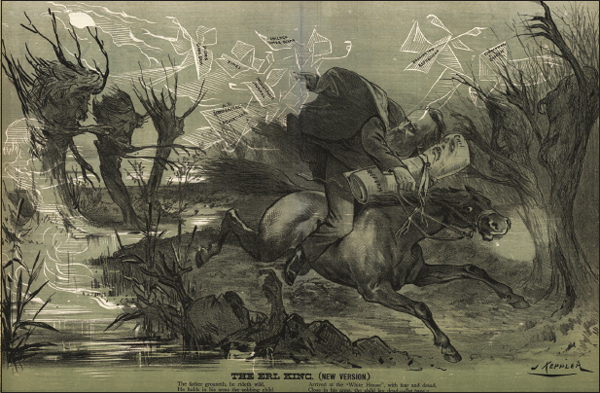

Rutherford Birchard Hayes won the presidency with a minority of the popular vote and an Electoral College victory generally assumed to be rigged. None of this was his doing, however, and he tried to atone for these circumstances by removing most federal troops from the Democratic South, and pursuing an agenda of Civil Service reform. His presidency stands, however, as an example of how good intentions can be subverted by a weak will and incompetent political instincts. In this allegorical Puck cartoon by Joseph Keppler, based on the Goethe poem, Hayes and his baby Civil Service Reform are haunted and pursued through the dismal swamp by shades of numerous enemies. Keppler was a clever artist, and often incorporated caricatures into tree branches and rock formations.

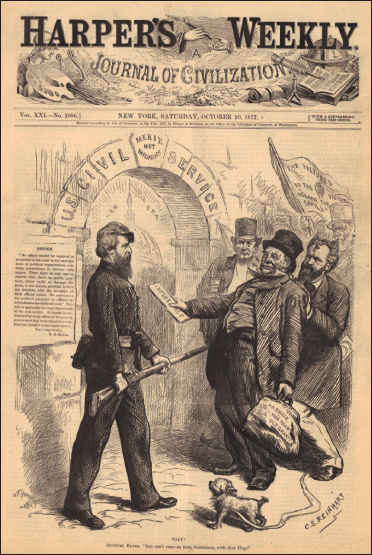

This C. S. Reinhart cartoon depicts the nub of the GOP intra-party battle that settled in the controversy surrounding TR's father. Harper's Weekly portays Hayes as guardian of the gate to the new era of Civil Service reform. Conkling, right, puts forward his candidate (“a bigger man than old Grant”—a current term of hyperbolic praise) who represents Chester Arthur, Collector of the Port of New York and boss of the Customs House, and other machine appointees. The month previous to this cartoon, Hayes had announced his intention to replace Arthur; within weeks he nominated Theodore Roosevelt the elder. Harper's Weekly editorialized: “The selection of Mr. Theodore Roosevelt for Collector is most admirable. For all the high character and ability which the duties of the place demand, Mr. Roosevelt is known to be in full sympathy with the principles of reform, and to have the force and courage to observe the…. [I]t is impossible that a man of the energy and firmness of Mr. Roosevelt should not make himself felt as a purifying force throughout the whole institution.”

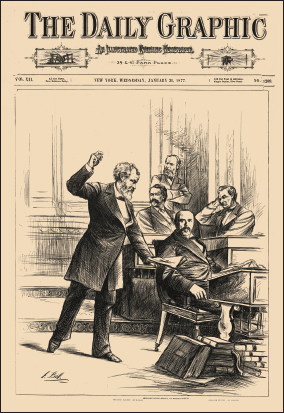

Roscoe Conkling was vain and arrogant, but he was a spellbinding orator. In the Senate, many colleagues considered his eloquence a prelude to grandiloquence. “The Titan” was pictured by the Graphic shortly before the episode of his sabotage of Theodore Roosevelt the elder.

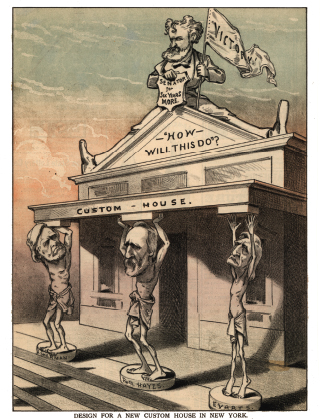

After Roscoe Conkling prevailed upon fellow senators to reject President Hayes' nomination of Theodore Roosevelt on the basis of senatorial privilege, Puck suggested this new design for the Port of New York headquarters.