RISING LIKE A ROCKET

Indeed, life went on, and sunshine returned to TR's life in the person of Alice Hathaway Lee. His previous “understandings” (such as with childhood friend Edith Carow, who almost all their friends assumed would become his wife) were set aside. His diaries were crowded now with Alice. His letters home and chats with friends were generally on two topics: Alice and Alice. When planning hunting trips to the northern plains and the Rockies with Elliott, he told everyone how he would miss Alice. He arranged all sorts of “sprees” with common friends and with Chestnut Hill relatives of his classmates, just to see Alice. In the emotional hyperventilation common to the Victorian Era, TR was dramatic about his love, jealous of Alice's attention, and suspicious of possible rivals. Alice had rejected multiple marriage proposals from “Teddy” (her nickname for him, and one which, except for Alice, he strongly discouraged anyone from using), frustrating him often. Finally she relented, accepted his proposal, and never again confessed to anything other than head-over-heels love and devotion for him. The reasons for Alice's reluctance could have been anything from her beau's headstrong nature to her own youth (she was only seventeen when they met). Possibly she was repelled by the scent of arsenic and other singular fragrances attendant to the practice of taxidermy—for TR still collected and studied animal specimens with avidity, and his living space reeked of the hobby. But Alice evidently discovered that even a dainty debutante's nose can grow accustomed to almost anything, when the heart leads the way.

After TR's graduation from Harvard, near the top of his class, the couple married in Brookline, Massachusetts, on October 27, 1880—his twenty-second birthday. Their honey-moon was delayed due to Roosevelt's acceptance to Columbia Law School in New York. (He did not take many courses, eventually leaving law school and a possible career behind, convinced that too much of the law “was devoted to getting people off the hook.”) The young couple moved in with the widowed Mittie in the Roosevelt mansion on 57th Street, discussed plans for a country home in Oyster Bay, on Long Island's North Shore, and finally honeymooned in Europe.

Before the honeymoon, the young husband was examined by a doctor who grimly diagnosed a heart malfunction, a weakness that mandated TR never again exert himself. Roosevelt responded by scaling the Matterhorn in Switzerland on his honeymoon. (It had been scarcely more than fifteen years since climbers conquered the mountain, and four members of the original eight-man party died in the attempt.) There is no record that Alice disapproved—we can wonder whether it would have dissuaded her Teddy—but neither is there any record that she showed an interest in joining his vertical spree.

Back in New York City, young Theodore was not settled about a profession, although he was certain that he needed to support his wife and (he hoped and assumed) a large family. He had a visceral aversion to the practice of law, despite applying to Columbia and briefly clerking in the office of his uncle, Robert Barnhill Roosevelt. To any of the traditional Roosevelt businesses, such as banking or glass importation, TR likewise felt no attraction. The disinclination possibly had something to do with the fact that numbers and figures flummoxed him, then and throughout his life. He had an interest in the literary life, and he invested in the publishing house of G. P. Putnam's Sons, although he never performed any managerial or editorial duties. Along with numbers, TR had a lifelong problem with spelling. Although he became a prolific author of books and magazine articles, his spelling was abysmal. To his last days, for instance, he wrote “do'n't” instead of “don't.”

While Roosevelt sorted out his options for occupation, he certainly was not idle. He worked with astonishing intensity on a book he had begun at Harvard, The Naval War of 1812. Two uncles on his mother's side had been prominent in the Confederate Navy and had exiled themselves to England after the war. Theodore and Alice called on them during their honeymoon tour, and TR peppered them with questions for his book. He finished The Naval War in New York, in the midst of involvement in civic affairs, emulating his father's charitable visits around the city, and brief stints fox-hunting in the country. The lengthy book was released in 1882, and was widely praised for its thoroughgoing accuracy and impartiality. It was accepted into libraries of Royal war colleges, as well as those of American historians and military personnel. The Naval War of 1812 continues to be one of the standard works on the subject. Theodore Roosevelt was twenty-three at the time.

The American political scene had recently experienced changes. In the presidential year of 1880, President Hayes declined to stand for reelection. Former president U. S. Grant allowed himself to be pushed for a third term by the Roosevelts' nemesis Roscoe Conkling. Various anti-Grant politicians, including Senators John Sherman and James G. Blaine (commonly called Half-Breeds) jockeyed for the nomination, eventually creating a convention stalemate. Dark horse Representative James A. Garfield of Ohio was the compromise candidate. The convention attempted to placate the defeated boss Conkling by nominating Chester Alan Arthur for the vice presidency.

Thus the Roosevelt name echoed once again in national political discussions, referring to the recent imbroglio involving TR's father; one can imagine how personal—and personally offensive—the reminders must have seemed to the younger Roosevelt.

The Garfield-Arthur ticket was successful, defeating the Democrat nominee, Civil War hero of Gettysburg General Winfield S. Hancock. The Roosevelt family's association with Arthur took an even more bizarre turn when, during TR's honeymoon, President Garfield was assassinated, shot in the back at a train station by disappointed office-seeker Charles Guiteau. In a symbolic and dramatic manifestation of the entire cesspool of grasping ambition and political corruption of the time, Guiteau shouted, “Garfield is dead, and now Chet Arthur is president!”

Would reform of the civil service and party politics finally attract adherents of substance? Gentlemen were disgusted by the state of politics at the time, and “decent people” eschewed politics. For this reason friends had been startled when the elder Roosevelt accepted the president's nomination to manage the notoriously graft-ridden Customs House. The same friends would be doubly surprised at young TR, who decided to explore becoming what he called “part of the governing class” rather than to disdain it, and to enter at the ground floor, although he shared the general disgust with politics. The 21st District Republican Association was technically on the second floor, over a saloon, and TR must have looked out of place at the meetings. Young, nattily attired, with side-whiskers, he socialized with men who were, precisely as his proper friends had warned him, saloon-keepers and horse-car conductors. But TR had determined to be a member of “the governing class,” and not leave it to the proprietorship of anyone not a “gentleman.” The district was “silk stocking,” a mixture of wealthy and working-class families; the smoke-filled meetings themselves were dominated by rough types whose experience in politics was closer to stealing ballot boxes and “influencing” voters than quoting the Federalist Papers.

The local Republican boss was a former Tammany Democrat, Jake Hess, and the organizational rival was Irish immigrant Joe Murray. TR became the beneficiary of a minor power struggle when Hess's choice for the state Assembly seat was checkmated by Murray's successful nomination of young Roosevelt. Hess took his own defeat good-naturedly and joined the canvass for TR. It was a campaign that would require attention, the political leaders soon realized.

While doing the rounds of the district's influential supporters, Roosevelt was introduced to a saloon-keeper, who hinted that he expected favors to the liquor interests to continue, and that he thought operating licenses for saloons were priced too high. Roosevelt replied that he intended to treat all constituents evenly, with no favors; he added that, personally, he considered the saloons should pay higher, not lower, license fees. For the balance of the campaign his appearances were arranged with his “father's friends,” the bluebloods and upper-class residents of the district; guys like Jake and Joe visited the rest. Endorsements of TR by prominent citizens included the signatures of Joseph Choate (noted attorney and later a distinguished diplomat), and Elihu Root (later Secretary of War under presidents McKinley and Roosevelt, Secretary of State under TR, and eventually a U.S. senator). Roosevelt easily won election, supported by disparate constituencies of a hybrid electorate, and as the son of his prominent father, the noted reformer.

TR was a quick study in parliamentary procedures; he was also headstrong. It was not the custom for freshmen to introduce much legislation in their first year, but within a month of being sworn in, TR introduced four reform bills; one passed. Because his reform efforts drew attention, he quickly drew prominent committee assignments and became a member the GOP leadership in the Assembly.

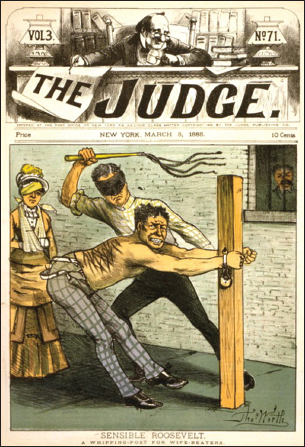

Possibly the first cartoon mentioning (and perhaps picturing, through the window) Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Worth's cover cartoon in Judge, March 3, 1883, praises “Sensible Roosevelt” for sponsoring a bill that sanctioned the whipping post for men convicted of beating their wives. It failed to become law.

Newspapers, rivals, and even members of his own party did not exactly know what to make of the intense 23-year-old. In those days, Roosevelt was seen as a “dandy”—and indeed, he cultivated the impression. He wore tight pants and colorful vests; he often wore sashes and carried a gold-headed cane; he sported tan kidskin gloves and wore spats. He affected a Harvard accent (which he chose to employ his whole life) and was derisively pictured in a newspaper report as applauding with the tips of his fingers and uttering phrases like, “I am rawther re-lieved.” But many stories survive of surprises delivered to those who thought him a sissy or a pushover. When TR heard that one Assemblyman wanted to recruit cronies to toss TR in a blanket outside the Capitol, he immediately confronted the bully, telling him: “If you try anything like that, I'll kick you, I'll bite you, I'll kick you in the balls, I'll do anything to you—you'd better leave me alone.” The prank was never attempted. When another Assemblyman made fun of TR's appearance across a tavern one night, Roosevelt walked right over and punched him in the face. When the man arose, Roosevelt knocked him to the floor a second time. Finally TR helped him up and said, “Now you go over there and wash yourself. When you are in the presence of gentlemen, conduct yourself like a gentleman,” and ordered the man a beer. This was in keeping with the advice of his father, as TR would recall: “He certainly gave me the feeling that I was always to be both decent and manly, and that if I were manly nobody would laugh at my being decent.”

Then the bold freshman Assemblyman dropped a real bombshell: in the first weeks of 1882, he announced his intention to formally investigate Judge Theodore Westbrook, generally recognized as prepatory to moving articles of impeachment. TR had discovered that Westbrook granted outrageous favors to elevated railway lines in New York—setting values, harming competitors, and defrauding investors—that benefited financier Jay Gould. In fact, before his rulings, the judge met with Gould in the latter's hotel suite. Now the press and statewide electorate, and not only fellow legislators, took notice of Theodore Roosevelt, and for substantial reasons.

Young TR did his homework. He conducted hearings, orchestrated a release of information to newspapers, and navigated the waters of Assembly procedures. However, he was a pilot without sufficient experience, and his efforts were thwarted twice, with bribes to Assemblymen, parliamentary maneuvers, and other methods even more sinister. A wealthy friend of his father's generation privately advised TR to “go along” with the system, now that he had made his “splash.” (TR later cited this as his first personal introduction to the invisible collusion between corrupt politicians and malefactors of great wealth.) Then, one night in Albany, a woman fainted on the sidewalk in front of him. Ever the gentleman, Roosevelt hailed a cab and took the woman to her address. When she insisted he take her to her rooms, he grew suspicious. After leaving her at the door, he had the house watched, and discovered that men were waiting there to frame and “expose” him in an affair for the ultimate purpose of blackmail. Every attack, and even his highly publicized hearings on Judge Westbrook, taught TR how to carry on the fight for reform. (Westbrook was found dead in his rooms, a possible suicide, several weeks after he “survived” the investigation.)

TR stood so squarely in the public eye after only one term that his caucus nominated him for Speaker of the Assembly. As Republicans were in the minority, his election was unlikely, but the process resulted in his becoming Minority Leader. He took on more duties, researching legislation, managing his caucus, and pushing reform measures. He spent the long, busy weekdays in Albany, and commuted by train to Manhattan for weekends with Alice; she seldom joined him in the relatively backwater state capital. Through it all, he wrote articles for magazines and maintained a proper and very busy social life. A staunch Republican, he nevertheless publicly cooperated with the new reform-minded Democrat governor Grover Cleveland. They were brothers under the skin: Cleveland, former sheriff of Erie County and mayor of Buffalo, was called “ugly honest,” and was once praised with the greatest compliment a reformer can receive: “We love him for the enemies he has made!”

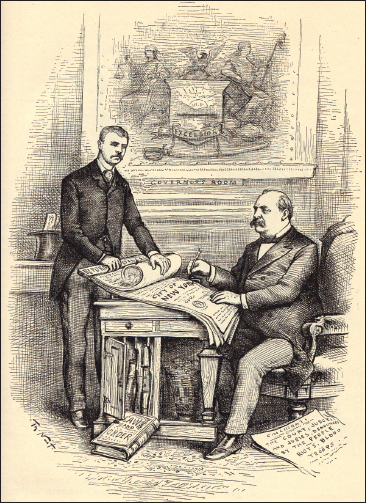

Now that Roosevelt's reputation was extending beyond his district, city, and even New York State, he also attracted the notice of cartoonists. Then, as now, cartoons provided a barometer of a politician's public standing. Though still young and wiry, Roosevelt's distinctive features were the stuff of caricature—moustache, pince-nez, and the look of fierce determination. Puck, America's first successful cartoon magazine, featured TR in front-page and center-page cartoons. Thomas Nast, the “Father of American political cartooning,” whom Abraham Lincoln had dubbed “the North's best recruiting sergeant” for his pro-Union drawings, and whose cartoons in Harper's Weekly had brought down the Tweed Ring and assisted in the defeat of Horace Greeley in the presidential election of 1872, unknowingly heralded two future reform-minded presidents when he pictured Roosevelt and Governor Cleveland cooperating on reform measures.

Thomas Nast, the Dean of American political cartoonists, drew some of the first nationally published cartoons of Theodore Roosevelt. Some featured the unknown young reformer with the new governor of New York, also a young and unheralded reformer, Grover Cleveland. The two men cooperated on legislation that impressed people of both parties, as well as crusading cartoonists. From Harper's Weekly.

Meanwhile, the young politician was learning that there were institutional evils that threatened republican government and the economic system itself. And the problem ran deep, because tainted officials like Westbrook allowed graft or sanctioned the ruin of honest competitors from a sincere motive: to maintain the “greater good” (at least in their view) at all costs. Wealthy members of TR's class sincerely regarded oppression and manipulations as necessary, minor evils. Their philosophy in the face of obvious corruption tended to be, “Don't rock the boat.” This did not sit well with TR. He began to realize that coarse and corrupt petty politicians were no worse threats to a republican democracy than were refined and corrupt prominent men of influence. This came as no surprise to a young man whose father had accorded the same respect to an orphaned newsboy as he did the moguls with whom he discussed numerous charity projects. The Roosevelts understood that honesty and integrity demanded respect, no matter a person's social standing, while wrongdoing should incur blame, regardless of one's high reputation or status.

A tour of cigar-making shops in lower Manhattan really opened Roosevelt's eyes to the social problems that were rampant at the time. (He was invited to witness the conditions first-hand by Samuel Gompers, four years previous to Gompers' founding of the American Federation of labor.) The shops were located in neighborhoods teeming with overcrowded tenements and sweat-shops. New Yorkers were well aware of these ghettos; TR himself had accompanied his father on visits to missions in their streets. Yet few citizens actually climbed their stairs, and fewer were outraged by the social, health, and economic ills prevalent there. Visiting the dark rooms where large families slept, ate, and rolled cigars or sewed shirtwaists eighteen hours a day obliged TR to open his eyes. His concern was quickened by the fact that some families in his social set uptown profited from the businesses whose goods were made in those tenements. Additionally, anarchists and socialists were increasingly active in the neighborhoods, attempting to recruit adherents.

TR determined to reform those conditions—the system behind them, if it could be done—in the name of justice; this became a thematic preoccupation of his career: not reaction, not revolution, but realizable reform. His was a conservative impulse that might resort to radical means. He set to work immediately, holding hearings and introducing legislation to alleviate conditions in the slums and reform the bureaucratic corruption that allowed for countless violations of law and regulation.

When Roosevelt began his third term in the Assembly in 1884, the Republicans were in control, the beneficiaries of the gathering tide of reform across the country. The Pendleton Civil Service Act, a mild but significant reform expanding the percentage of merit appointments in federal government jobs, had become the law of the land. In Albany, TR did not receive the nomination for Speaker of the New York Assembly. While his colleagues were willing to make him Minority Leader, they were not quite ready to elect him Speaker. TR was, understandably, disappointed. He bitterly regretted doing scant spadework on his campaign (he had taken the attitude that the office would find the man) and the unreliable assurances of his colleagues that the Speakership would be his. He later wrote, “I rose like a rocket and then came an awful cropper, and had to learn from bitter experience the lesson that I was not all-important.” But he would never forget this crash course in practical politics, and the primacy of nitty-gritty organization. The routine but tedious work of identifying allies and opponents, “counting noses,” and other such everyday political activities thenceforth became second nature. In fact TR grew to enjoy the nuts-and-bolts of politics, and in later years he stoutly defended the “practical” side of politics.

Always resilient, TR spent little time licking his wounds before plunging back into his work, doing what he could, with what he had, where he was. Whether as consolation prize or by merit, he was named chairman of the powerful Cities Affairs committee, and he undertook a task more daunting than any he had previously set before himself: to restructure the entire municipal government of New York City. The most practical means to effect reform of that corrupt system, he believed, was to transfer power from the non-elected Board of Aldermen (most of them beholden to party machines) to the office of the currently powerless but popularly elected—and accountable—mayor of the city of New York.

As he prepared for this gargantuan task, two other matters also absorbed his attention. First, TR was determined to play a role on behalf of reforming the GOP at the Republican National Convention in several months. He wanted to see a “pure” standard-bearer nominated.

The other matter was less prosaic, but it fairly blotted out any other concerns about political defeats or crusades. Alice was pregnant. TR was bursting with joy at the prospect of being a father. Now he could emulate his own father, who had fulfilled Proverbs 22:6, “Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old, he will not depart from it.” Roosevelt was eager to establish his own family in the same manner.

While he was at work in the Assembly on February 13, 1884, word reached Roosevelt that Alice was delivering their child, and in distress. An unusually heavy snowstorm raging between Albany and Manhattan made travel excruciatingly slow. When TR finally arrived at the family home on 57th Street, he was met at the door by his brother Elliott, who told him: “Alice is dying. Mother is dying too. There is a curse upon this house.”

Indeed, both ladies were fevered and insensible. Alice had given birth to a healthy baby girl, but was dying of Bright's Disease, a kidney ailment. Mittie was dying of typhoid fever. She had always been a virtual germophobe—one of her eccentricities—but this dread disease appeared suddenly, despite all her precautions, and now threatened to claim her life. Theodore spent the night going up and down the stairs, from bedside to bedside. His mother died first. He trudged upstairs once more and held Alice's hand and mopped her fevered brow in the hours until she also died.

Roosevelt was inconsolable. His diary entry on the occasion was nothing but a large X and the legend, “The light has gone out of my life.”

At the double funeral, attended by throngs of mourners, nearly everyone, including the pastor conducting the service at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, was sobbing. But not Theodore, who simply sat as if in a daze in the front pew; witnesses said he seemed insensible to the events of the funeral and the double burial at Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, resting place of many prominent New Yorkers.

Afterwards he summoned the emotional strength to publish a memorial for close family and friends. He wrote about Alice:

She was beautiful in face and form, and lovelier still in spirit; as a flower she grew, and as a fair young flower she died. Her life had been always in the sunshine; there had never come to her a single sorrow; and none ever knew her who did not love and revere her for the bright, sunny temper and her saintly unselfishness. Fair, pure, and joyous as a maiden; loving, tender, and happy as a young wife; when she had just become a mother, when her life seemed to be just begun, and when the years seemed so bright before her—then, by a strange and terrible fate, death came to her. And when my heart's dearest died, the light went from my life forever.

Theodore composed himself sooner than most souls could, and returned to the legislature two days after the funeral. He explained grimly, “I shall come back to my work at once; there is now nothing left for me except to try to so live as not to dishonor the memory of those I loved who have gone before me.” Assemblymen of both parties, including enemies and Tammany men, paid tribute to their colleague and his departed darlings; again, there were few dry eyes in the chamber. Then the Assembly adjourned in mourning, a gesture usually reserved for actual members who died.

Now TR worked like a dynamo, at a faster and more intense pace than he ever had before on any project. He drafted many reform bills, all complex and formidable. He held hearings in Albany and extensive hearings in Manhattan, even on weekends. He wrote out the bills longhand, making numerous corrections; and when opponents attempted subterfuge by manipulating deadlines for reporting and voting, he worked through the nights and even sent the bills page by page to the Assembly printer. At the end of the whirlwind, nine bills were reported from committee, and seven were passed by the full Assembly. The sheer work involved was an astonishing achievement, a testimony to Roosevelt's energy and his ability to create public pressure through publicity and the press, a gift he learned to cultivate with increasing cleverness and effectiveness. In three short terms in the New York Assembly, TR was responsible for a host of reform legislation, from civil service corrections (informally called the Roosevelt-Cleveland Law) to workplace safety (the Cigar Bill) to reforms of New York City utilities, operations, and charter.

When the Assembly adjourned in April of 1884, TR “relaxed” by throwing himself into work preparatory to the Republican National Convention. He wanted to see the nation's rising tide of reform float the GOP's boat. In recent elections, the major Republican factions, Half-Breeds and Stalwarts, had proven equally corrupt. So it appeared that James G. Blaine, a senator from Maine who was a magnetic leader, a capable politician, and a political hero, had a good chance at the nomination. As it turned out, though, he had feet of clay. Through the years, going back to his days as a congressman and Speaker of the House, Blaine's record was littered with incidents—and incriminating documents—of soliciting money for legislation, peddling influence, and even destroying evidence. Nevertheless, after seeking the presidency in 1876 and 1880, it seemed to be his time in 1884. Garfield was dead; Grant was close to death; Conkling was off the stage; and President Arthur, who desired renomination, was a lightweight foe.

Reform-minded Republicans were aghast at the possibility of Blaine's nomination. Roosevelt and a new friend, Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, late member of his state's lower house and Lecturer at Harvard during TR's student days, mobilized themselves on behalf of a candidate they believed could serve the cause of reform, Senator George F. Edmunds of Vermont. They worked tirelessly to gather delegates' commitments, and to persuade others to withhold their commitments until the actual convention balloting. They conferred with dark-horse and favorite-son figures on the national scene. In their efforts they formed a phalanx of prominent reform-minded Republicans, including George William Curtis, editor of Harper's Weekly, and Carl Schurz, the German immigrant who had fought in the Civil War and led the “Liberal Republican” revolt against President Grant's reelection back in 1872.

Significantly, TR never even considered supporting President Arthur's renomination. Although Chester Alan Arthur had changed his spots when he assumed the presidency and surprised many citizens with decent if unspectacular support of civil-service reform, TR must have found it nearly impossible to think of him as anything other than the corrupt Collector of the New York Customs House, whose refusal to vacate his office had so humiliated TR's father a few years earlier. Although TR's surviving letters and the memoirs of his associates reveal no evidence of resentment or revenge, it is difficult to believe that Roosevelt would have been able to countenance Arthur's renomination, much less his reelection.

Roosevelt was elected co-chair of the New York State delegation, by virtue of his position in the state party and his vaunted accomplishments in the Assembly, as well as a deadlock between the convention forces of Arthur and his opponents. At the convention, TR assiduously worked the aisles and back-rooms on behalf of a reform platform and reform candidate. His first speech on the national stage was the emotional nomination of John R. Lynch to be convention chairman. Lynch, a former slave, late Speaker of the Mississippi House, and now a U.S. congressman, was elected chairman after TR's speech. In the end, “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine, the continental liar from the state of Maine” was nominated for president. But Theodore Roosevelt, just twenty-five years old, was one of the most conspicuous and influential figures in the convention.

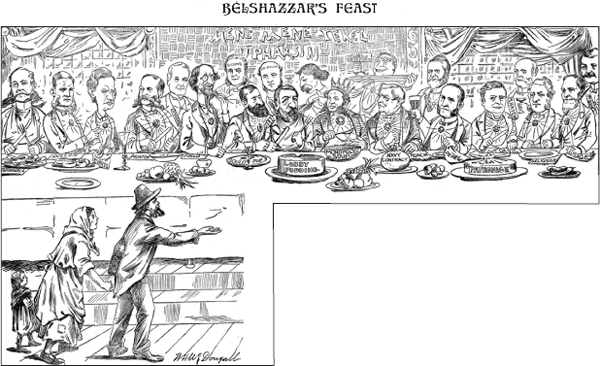

“The Royal Feast of Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings” referred to a dinner given to Blaine at Delmonico's restaurant by leading financiers a few nights before the election. The cartoon was printed in The New York World and distributed widely, especially to the clichéd poor folks in the lower left. It was a collaboration between Walt McDougall and Valerian Gribedayeff (who drew likenesses better than McDougall).

With Blaine as the party's nominee, Roosevelt was deeply conflicted during the canvass. Many of his confreres in the reform movement bolted from the party rather than support Blaine. This decision was easy to understand, especially when the Democrats obligingly nominated the paragon of reform, TR's sometime ally Grover Cleveland, Governor of New York State. But Roosevelt and Lodge decided to stay and work within the Republican party. They admired Cleveland to a point, but they could not abide the Democrats' passel of sectionalism, incipient corruption, and assortment of municipal machine bosses. Roosevelt and Lodge were vilified for their decision by their former allies and independent publications. Many cartoons had welcomed TR to the national stage in 1884; now, many more skewered him for “deserting” the forces of reform.

The intensity of the Assembly, his daughter's birth, the deaths of Mittie and Alice, and the hyperactivity of the convention work had all taken their toll on Roosevelt. Longing for solace and a change of scene after months of turmoil in both his public and his private life, he decided to retreat from it all. He left his young daughter, Baby Alice, in the care of his sister Bamie, and set his sights on an area that had previously beckoned: the Badlands of the Dakota Territory, far from politics and memories, newspaper reporters and cartoonists. He had already been there for hunting trips in the past, and he was intrigued by the bizarre landscape and compelling environment; now he decided to return for a spell.

1878-1884: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE APOTHEOSIS AND FALL

OF ROSCOE CONKLING

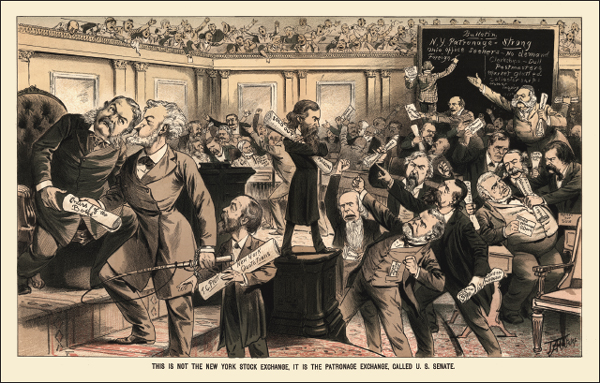

The political faction that humiliated Theodore Roosevelt's father was immediately triumphant, and even more in the next couple years. Political hack Chester Arthur was, of all things, vice president of the United States and—as this J. A. Wales cartoon from Puck illustrates—still taking orders from Boss Conkling. The setting is the U.S. Senate, which was not far removed from the influence-peddling marketplace that Wales pictured. A center spread from 1881. Thomas C. Platt, later GOP Boss of New York, is depicted here as the little fellow at Conkling's side.

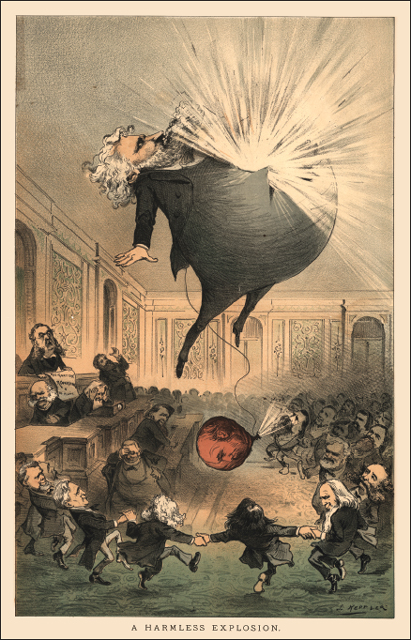

A cartoon that would have pleased TR's late father. Joseph Keppler of Puck depicted the haughty resignation of the Stalwart boss of the Senate, Roscoe Conkling. After winning a showdown with President Hayes (in which the elder Roosevelt was a pawn), Conkling lost a similar showdown with the new president, James A. Garfield. He and the junior senator from New York resigned, expecting to be vindicated by the Albany legislature and reappointed as senators. To the surprise—and humiliation—of the two men, the state legislature did not comply. Fellow senators in Washington, at least in Keppler's cartoon, were similarly dismissive of the overblown Conkling. The sputtering little balloon is junior Senator Platt, who slowly rose again to prominence to become TR's uneasy fellow leader in state and national politics.

1878-1884: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

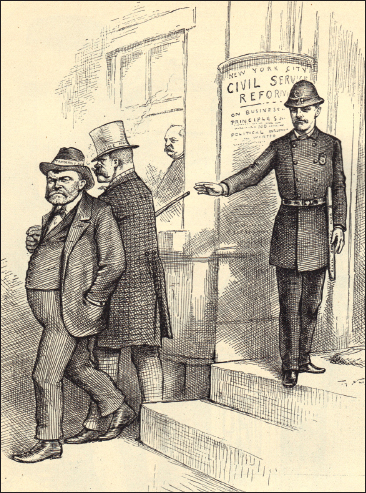

NEW YORK ASSEMBLY

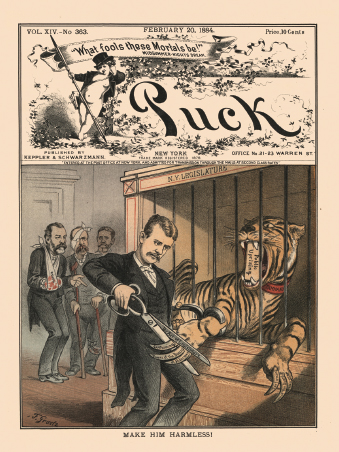

Some of the very earliest political cartoons featuring Theodore Roosevelt were on the front covers of the greatest showcases he could have desired, and they were laudatory, not critical. Puck was well known as a crusading, reform-oriented publication, and in 1884 it was to score its big successes in the presidential campaign, contending against James G. Blaine. Naturally, Tammany Hall, the nation's hothouse of political corruption, was always a target. Roosevelt had made real progress in the Assembly, exposing the Democrat machine, drafting legislation, and pushing a complete overhaul of the city's charter, so as to curtail Tammany's virtual oligarchy. The first cartoon was published a week after TR's wife and mother died. It depicts Roosevelt toward the end of his work, while former NYC mayors, bloodied from their own unsuccessful fights, look on.

In the cartoon a month later, Governor Cleveland has joined Roosevelt, and the wounded and temporarily harmless Tammany tiger wears the face of its boss, John Kelly. The cartoonist was Friederich Grätz, an Austrian who was on Puck's staff for three years.

1878-1884: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE 1884 CAMPAIGN

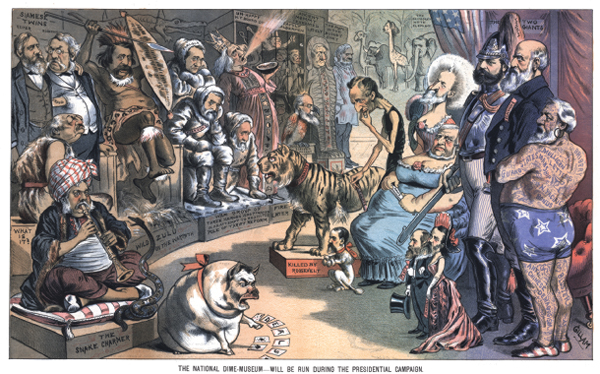

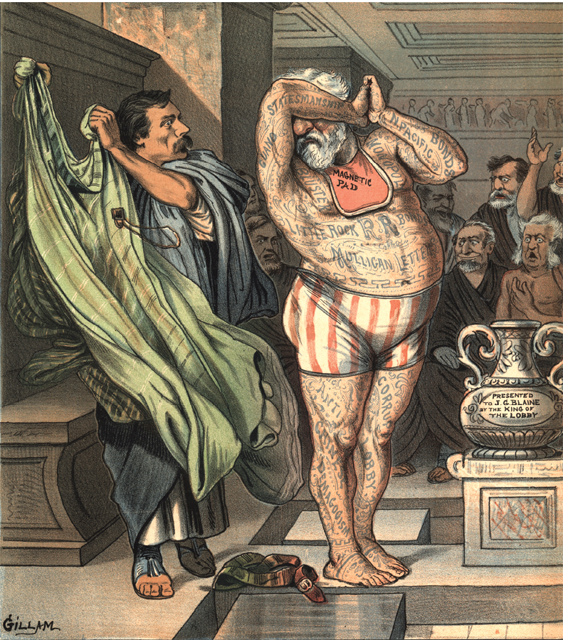

Puck magazine opened its 1884 presidential campaign season with a center-spread cartoon of “the National Dime Museum,” a sideshow of all the personalities and issues in contemporary politics. An unintended consequence of Bernard Gillam's cartoon was the depiction of James G. Blaine as a tattooed man, his many political sins and indiscretions apparent to all—and indelible. The depiction created a sensation, and Puck continued with Blaine's image so festooned throughout the campaign, to enormous public attention. The “Tattooed Man” cartoons were viewed as major factors in candidate Blaine's subsequent defeat, and they put Puck firmly on the map. As influential cartoons, this series is on a par with Nast's Tweed Ring series in Harper's Weekly in 1871.

The other notable aspect of Gillam's cartoon is the sideshow's display of a stuffed Tammany tiger, prominently in the center of the drawing, “killed by Roosevelt.” The label, like reports of Mark Twain's death, was greatly exaggerated, but TR's work in the Assembly had wounded the political machine in the extreme, and this cartoon confirmed the public's perception of the young reformer.

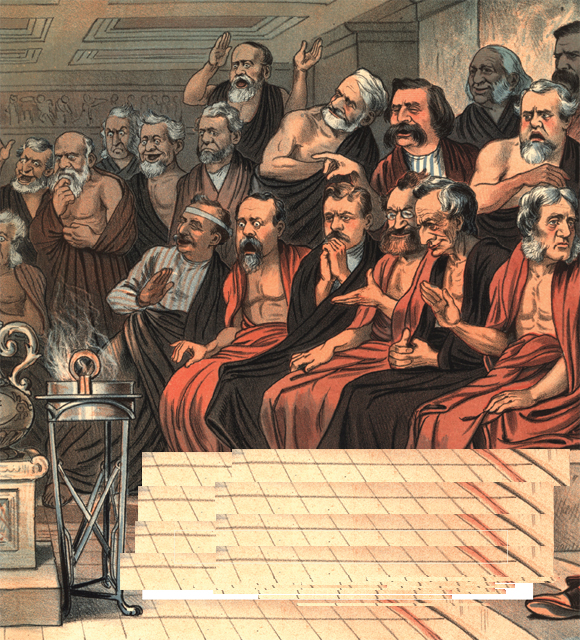

One of the most effective—and most famous—political cartoons in American history, and Roosevelt is at the center of it. Of course James G. Blaine, the Tattooed Man, is the subject. But as he is revealed by Whitelaw Reid, editor of the Republican party's chief organ The New York Tribune, the tribunal needs to be convinced. In Gillam's cartoon, the national GOP leaders are variously dismissive, shocked, or troubled. TR is the thoughtful young man (barely twenty-five, surrounded by veterans and graybeards of the establishment) in the front row. To his left are Carl Schurz, seasoned reformer; Senator William Evarts; and Harper's Weekly editor George W. Curtis. Above Roosevelt is Senator John Sherman with a white beard; and, pointing, General John A. Logan, who would be Blaine's running mate. The cartoon was modeled after a famous painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Phryne Before the Areopagus. Gillam's caricatures are masterful; he forsook labels in this cartoon. No one could fail to recognize Blaine, even though most of his face is obscured.

Immediately after Cleveland's election in 1884 (and possibly pre-drawn in the case of his defeat, a practice cartoonists of the day employed because of advanced deadlines), Joseph Keppler of Puck celebrated the surge of Reform in America. Among the movement's leaders he depicted the figure of Puck, and the magazine's symbol of the Independent New Party, a putative third-party option if the Democrats were to disappoint.