“BLACK CARE RARELY SITS

BEHIND A RIDER WHOSE PACE

IS FAST ENOUGH”

Theodore Roosevelt was not exactly certain what he would do with his life. He had risen “like a rocket” in the New York State legislature, nominated by his party for Speaker in his second term. As co-chairman of the state's delegation to the presidential nominating convention, he became a major force in that convention and in the ensuing national campaign. Now, with the presidential campaign barely over, the twenty-six-year-old Roosevelt considered his political career—and more importantly, his political future—in shambles. To a man accustomed to doing several things concurrently—reading Thucydides and riding the range, writing history books and hunting elusive white-tailed deer, engaging in raw political fights and visiting chapels in the Newsboys' Lodging-House—it was a rare thing for TR to feel at a loss over what to do.

The young Roosevelt had gained a different perspective on politics, if not a career in public service, by the end of 1884. He had learned from mistakes, both of hubris and immature political calculations, in the legislature—but the lessons learned couldn't change the fact that mistakes had been made. Veteran politicians, whether sworn enemies or wary allies, have long memories. TR had been a hero of reform elements and independents, both of which he bitterly disappointed when he chose to remain in the Republican party and support James G. Blaine in his run for president. TR had learned that these types in politics, “professional do-gooders,” could be as vicious as the political bosses they despised. They were willing to sacrifice progress in the name of abstract purity. And the Republican establishment was not wildly enthusiastic about embracing its prodigal son: the upstart had made it clear that he was a maverick unwilling to play by the rules; worse, he was obviously impatient to establish his own rules. He didn't know his place.

In many ways, his personal life at this time seemed as bleak as his professional life. The death of Alice remained a hole in his heart. It was her death, and his mother's only hours earlier, that largely drove him to forsake another term in the legislature. The dilemmas he faced—including the fates of his healthy, bright baby Alice, and the half-built grand home in Oyster Bay—contributed to the inchoate decisions he made in 1885. His sister Bamie would raise Baby Alice for the time being, and the house could sit, half-finished, until he sorted out his life. In the meantime, he needed an income, whatever decisions he made. An Assemblyman's stipend would not suffice. In characteristic fashion, he settled on something rugged, adventurous, and highly unusual. His decision to move to the Badlands in the Dakota Territory and live the life of a rancher greatly surprised his friends and family.

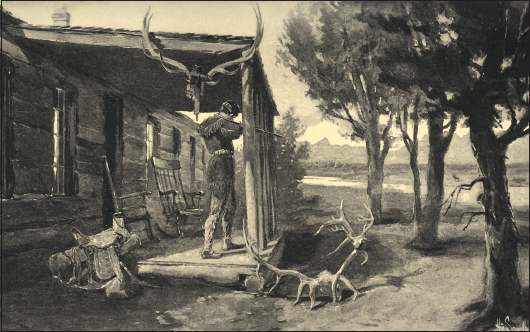

He invested a large portion of his patrimony in two ranches in the Dakota Territory. He hired from two pools: local men he met and trusted on sight, and Maine hunting-guides (friends from occasional hunts in the North Woods) whom he vetted with similar rigor. Dakota cowboys also joined the teams. TR bought thousands of head of Texas longhorn cattle, which a few years earlier had been found particularly suited to the rough terrain, short grass, and harsh weather of the Badlands. Because these cattle could thrive on the peculiar grass of the Badlands, cattle drives from Texas were no longer essential to the beef industry. Newly invented refrigerated railroad cars allowed cattle to be slaughtered and processed locally and sent to Chicago, ensuring efficiency and higher profits. Indeed, this enterprise was more than a romantic whim for him; Roosevelt intended to become a businessman, not just a cowboy, in the West. More precisely, although he did the work of cowboys, he was a rancher—responsible for his cowboys, and for an enterprise that he hoped would provide income for his family.

The wildness and the utter desolation of the Badlands held much of the attraction of this lifestyle for TR at this point in his life. A patrician from New York, he could easily have led the life of a dilettante, making occasional hunting trips to the Dakotas and remaining an absentee investor, focusing his attention on the business opportunities becoming so readily available in the West. Instead, he chose to establish his ranches in that portion of the West known as the Badlands.

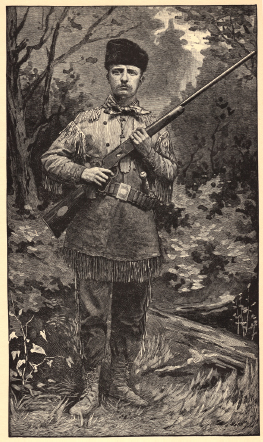

Roosevelt in the outfit of a Badlands hunter. Woodcut from his book Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (1885).

The Badlands were named for the other-worldly landscape of strange ravines, sulfur-steaming buttes, and bizarre vegetation. Legends say that early French trappers called the territory “a bad land to travel through.” It was also a land full of bad men. The town near Roosevelt's ranches, Medora, was not far from Deadwood, whose legend exaggerates little. Some men populated the Badlands because they wanted to forget things—TR fairly can be added to that category; some inhabited the place in hopes that others (for instance, the law) would forget them. Even “frontier” justice was a scarce commodity. Drinking was rife; accounts were settled (as were some minor grudges) with guns; survival in its many forms was a daily challenge. The Dickinson Press in 1884 wrote about attempts to tame Billings County: “If there is any place along the line that needs a criminal court and jail it is Medora.” Caricatures (like the drawing by J. H. Smith in Judge's Library on the previous page) fit the popular conception of the cowboy, then and now, and they were not too far off the mark.

TR didn't just settle for this environment, however; he chose it. Neither did the supposedly frail “dude” from New York avoid its rougher aspects. In saloons he didn't drink liquor and generally kept to himself. On one occasion, however, a drunken bully claimed that “four eyes” would pay for everyone's drinks. Roosevelt later remembered that he joined in the laughter, but the bully only grew more surly. TR noted that the cowboy stood with his feet close together, and, drawing on early boxing lessons, he delivered a one-two punch that felled the bully and left him unconscious. Not only did the town's estimation of the “dude” rise, but the humiliated cowboy left town. In another incident that impressed those who spread the tale, one of TR's cowboys brought the calf of a rival ranchman to Roosevelt during a roundup. He showed how the calf's brand could be altered to resemble one of TR's own herds'. TR fired the cowboy on the spot. When the cowboy protested that he was only looking out for Roosevelt's interests, TR savagely replied: “Any man who will cheat for me will cheat from me.” Morality met practicality in the Badlands.

There were stories, too, that were less about specific events and more about TR's personality and pastimes—stories sometimes told in whispers, because here was a man whose type was not common, even in those rough lands and rough times. He frequently rode the plains alone, often at night, sometimes for days. We can suppose that lamentations for Alice and ruminations about his career rode with him. He wrote that “black care” was his constant companion, though he pointed out that “black care rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.” The very statement indicates a conflict between the presence or the escape from melancholia. Although he was clearly the boss of his ranches—his closest friends and employees in the Badlands always addressed him as “Mr. Roosevelt”—he invariably joined the roundups and drives. Frequently he rode a day and a half, without sleep, often in bad weather. Occasionally thrown from his horse or caught in a stampede, he rode through pain and sometimes with broken bones, never complaining. In one memorable cattle drive, he was in the saddle for forty hours straight, helping stop a stampede toward the end of the stretch. Many are the accounts of his outlasting seasoned cowboys or outpacing veteran hunting guides…usually to their astonishment, as well as their exhaustion.

Once a river scow of Roosevelt's was stolen. Bandits took it down the icy Little Missouri River. TR called two of his men, built a new boat, and headed out in pursuit. His cowboys tried to dissuade Roosevelt, arguing that the difficulty of chase and recovery outweighed the value of the scow. But TR wanted justice. On the third day out, having fought snow and icy waters, they located the robbers, who were surprised that anyone would have pursued them seriously. They also expected to be shot, which would have been routine frontier justice. As the nearest sheriff was in Mandan, at least two weeks distant, Roosevelt pointed the party to Dickinson, where there was a justice of the peace. The group fought icy waters for seven more days, then went overland for another two days. He and his impromptu posse took turns sleeping, covering the thieves with rifles. When they had run through their slim rations (bread made of flour and water so dirty that the bread was brown), TR dispatched one of his men to scout for a “cow camp” from which they might ask for victuals. Eventually the party arrived at the Stark County Courthouse in Dickinson. The justice of the peace who filed the complaint (and was astonished that TR had not simply shot the thieves on the spot) bore the unlikely but colorfully appropriate name of Western Starr. Roosevelt stayed until the thieves were tried the next day, and then he returned—this time by train—to Medora, thence to his ranch thirty-five miles north. The entire episode was an investment in righteousness for the untamed region, and it lasted about three weeks. And at odd moments—very odd moments—during the escapade, Roosevelt read a book he brought with him: Tolstoy's Anna Karenina.

The West carved new facets to TR's personality and his growing legend. The story of the outlaws, for instance, was spread far and wide. An astonished local even wrote a letter to The New York Times about “meeting a gentleman of his standing on the frontier, masquerading in the character of an impromptu Sheriff. But only such men, men of courage and energy, can hope to succeed in this new, beautiful, yet undeveloped country.” The writer noted an important distinction: TR was rough-and-tumble, but still a gentleman. He did not abandon his essential habits and breeding. When he and his men built and furnished the ranch houses—one was 60 by 30 feet, with eight rooms—there were shelves for many books, and quiet spaces to study and write. In the Badlands, between cattle drives and roundups, TR wrote two books—a collection of his ranching experiences, and a biography of the old Jacksonian stalwart, Senator Thomas Hart Benton. He mailed requests for some research materials to his sisters and to Henry Cabot Lodge, but otherwise the creditable biography was written from his memory of history and his reading.

TR, always an agent of civilization and reform, also had ambitions for his adopted region. Loathing the West's lawless character, he organized the Little Missouri Stockmen's Association, which addressed business affairs, cooperative action, the establishment of more places of justice and worship, and eventual statehood for the territory. (He declined suggestions that he run for office or represent the territory in Washington.)

As he had made occasional hunting trips to the West during his Assembly days, now TR made occasional trips back East to see his daughter and maintain contact with his affairs and friends. During one visit, he accidentally bumped into his childhood friend Edith Carow at his sister's house. Edith had been the sweetheart of his youth; in fact, many people had assumed they would marry, but then Alice happened. It is lost to history whether there had been a lover's quarrel between Theodore and Edith, or why. Likewise shrouded in mystery is what transpired after the chance encounter at Bamie's house; but evidently there were discreet meetings and exchanges of correspondence. Working his way through the guilt related to Alice's relatively recent death and Victorian customs that discouraged early (or any) remarriage, Theodore proposed to Edith. She accepted, and they managed to keep the engagement secret for a year.

Roosevelt now set his compass back toward New York City. He could accommodate the rough-hewn life on the frontier, but Edith never could. He would reclaim little Alice (a tough separation for both Bamie and her ward) and finish work on the home in Oyster Bay, which he renamed Sagamore Hill after the ancient Indian chief, instead of Leeholm in honor of his first wife (Alice Lee Roosevelt). When New York heard that Roosevelt was returning, the Republican Party persuaded him to run for mayor of the city where his ancestors had landed, settled, and prospered.

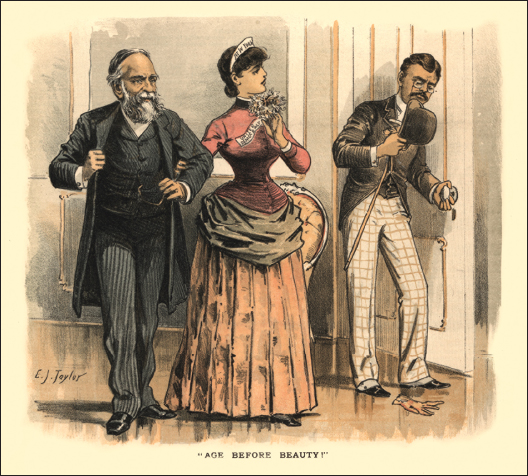

The nomination to run for mayor in 1886, however, given the local circumstances, was a relatively empty gesture, because the socialist Henry George was running on the Single-Tax platform and receiving unexpectedly widespread support. The Democrats nominated Abram S. Hewitt, a dignified industrialist, son-in-law of inventor and entrepreneur Peter Cooper, and no friend to Tammany Hall. In another year, young Roosevelt might have won the election, for his reputation as a reformer was still high. But he was a sacrificial lamb, and he knew it: the city's conservative element was so afraid of George's possible victory that many Republicans quietly voted for Hewitt. (Ironically, among Hewitt's investments were cattle ranches in the Dakota Territory, but the whitebeard was an absentee, and certainly no cowboy.)

Foregone conclusion or no, TR hardly ruminated over his loss. Within days of the election, he and Edith sailed for London, where they married. The best man was a junior diplomat met on the Atlantic cruise, Cecil Spring-Rice. He became a lifelong friend of Theodore and Edith and served as British Ambassador to the United States during TR's presidency.

In what was virtually a cosmic affirmation of TR's new life-detours, in the winter of 1886–87 the Dakota Territory sustained a blizzard whose severity seldom has been matched. Four-fifths of the local herds died, many frozen where they stood, and surviving cattle were emaciated. People literally were trapped in their cabins. Settlers' food supplies and firewood dwindled. Desperation reigned, and when spring returned, the Badlands were more desolate than ever. Even old residents moved away; churches and saloons alike closed; newspapers ceased publication; and the Medora meat-processing building was abandoned. Roosevelt's partners returned to their previous pursuits, his Maine comrades (and their families) moving back East. TR himself lost a fortune—a large portion of his inheritance, but perhaps more importantly his dreams—but it was time, for a variety of reasons, to move on.

Although frequently sentimental, TR was never a sentimentalist. He realized other, more lasting factors had heralded the end of the brief period of open ranges and cowboys. The blizzard might have damaged business prospects of ranchers, but barbed-wire fences and the influx of family farmers ended the lifestyle and romance, such as they were, of the cowboy. “The cattle-men,” TR wrote in Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (1885), “keep herds and build houses on the land; yet I would not for a moment debar settlers from the right of entry to the cattle country, though their coming in means in the end the destruction of us and our industry. For we ourselves, and the life that we lead, will shortly pass away from the plains as completely as the red and white hunters who have vanished from before our herds.” While he occasionally made hunting trips to the Badlands after this period, he fully divested himself of his ranches around the turn of the century and never returned to ranching for any extended time.

He was now a husband again, settling into a new Long Island estate with his wife and daughter and, in 1887, a son on the way. He commenced writing a biography of Gouverneur Morris of the American Revolution, as well as a monumental history of American expansion, The Winning of the West. The work eventually ran to four volumes, and is still regarded as an essential study of social and political history.

Again, politics beckoned. The national issues included a rising tide of labor unrest and urban violence, and a federal budget surplus which President Cleveland termed a national moral crisis, tantamount to theft from the citizenry (a situation perhaps unintelligible to modern readers). Cartoonists captured the public's fears of a French-style revolution and the budget problem (not a deficit like the budget problems we face today, but a real issue nonetheless). Roosevelt addressed both these topics, and others like them. Ultimately, however, TR's heart was not in his 1888 speeches, made on behalf of Indiana Republican Senator Benjamin Harrison.

Throughout this time, TR was busy, as always, especially with his writing. He did not expend much energy in pursuit of his own ambition. This was partly because friends like Henry Cabot Lodge were ambitious for him. Lodge, now a congressman from Massachusetts, was rising in the GOP, and began a decade's work of arranging higher and higher positions for his friend Theodore, who he believed was destined for great things. Benjamin Harrison won the presidency, and Lodge immediately advocated for TR to be a part of the administration. Thus the literary life of a Long Island patrician proved to be a short way-station for TR between cattle ranches and the nation's capital.

1885-1888: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

RUNNING FOR MAYOR OF NEW YORK

In a race for mayor of New York City, the white-bearded industrialist Abram S. Hewitt defeated Theodore Roosevelt, who turned twenty-eight a week before the election. In between them (not shown in this C. J. Taylor cartoon in Puck) was the single-tax theorist Henry George. The safe and sane Hewitt, who was the son-in-law of inventor Peter Cooper, received votes from Republicans alarmed at the prospect of George's labor supporters coming to power.

1878-1884: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

TR : FUTURE HOPE OF THE GOP?

A remarkable cartoon in a national publication, “Little Roosevelt! The Grand Old Party Must Be Hard Up!” (1887) Puck had pictured TR before, usually with favor; and it was

less than a year since Roosevelt had run for mayor of New York City. Nevertheless it was a compliment, even if a backhanded one, to the 28-year-old Roosevelt. In this image, the national Republican hierarchy of the day, including his friend Henry Cabot Lodge, is gathered around TR.

Puck ridiculed TR in its editorial:

“Mr. Roosevelt, be happy while you may…. Bright visions float before your eyes of what the Party can and may do for you. We wish you a gradual and gentle awakening. We feel the Party cannot do much for you…. You are not the timber of which presidents are made.”

In fifteen years, of course, Roosevelt would be not just timber, but president.