REFORM: “HE SEEN HIS DUTY

AND HE DONE IT!”

Henry Cabot Lodge had served one mere term in the U.S. House of Representatives by the time Benjamin Harrison was inaugurated president in March of 1889. He was a rising star in the Republican party due to the force of his personality, the pedigree of his ancestry and Harvard connections, and his important friendships. In his second term, Lodge co-sponsored the Federal Elections Bill, a landmark bit of civil-rights legislation. It protected voting rights of blacks in the South; Democrat opponents called it a “Force Bill.” Lodge had vigorously campaigned for Harrison, the diminutive former senator from Indiana and grandson of President William Henry Harrison.

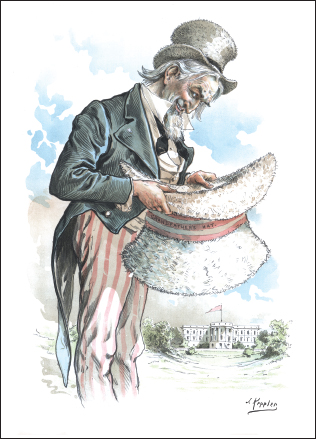

“Old Tippecanoe,” as the elder Harrison was called, was the shortest-serving president in history, dying just a month after his inauguration. His grandson Benjamin possibly became the shortest-looking president, thanks to cartoonists like Joseph Keppler of Puck, who emphasized Harrison's modest height by depicting him under an enormous hat (“Grandfather's hat,” implying that the only item on his résumé was his lineage). Indeed, Harrison had been a compromise candidate at the 1888 Republican convention. Several colorless hopefuls deadlocked in the convention, and in the end the former one-term senator Harrison was chosen.

Despite the general lack of enthusiasm over Harrison's nomination, Lodge canvassed for Harrison fervently, and he persuaded his friend Theodore Roosevelt to do the same. For Lodge, this type of canvassing and working for one's party was the natural activity of a professional politician. Although he had been branded a Reformer from the 1884 convention, “working from within the party” was what he proposed and lived out. In the future he was to become the Dean of the Senate, the first to hold the post of Majority Leader, and a major influence in foreign policy in the 1920s. Now, however, he was tending to his young career…and that of TR.

Lodge and Roosevelt were contemporaries, the former only eight years senior, and they developed a close and occasionally complicated friendship. Their politics were almost always synchronous, although Lodge was less conservative, and TR often more so, than history has portrayed them. Lodge and his wife Nannie—and their son George, a brilliant poet who died young—were intellectual companions of Theodore and Edith. Lodge's political ambitions were finite: he knew his limitations and frankly enjoyed living within them. His ambitions for Theodore, however, were without limit. He counseled and cajoled; he schemed and made appointments on TR's behalf; he lobbied Edith to persuade her husband to “climb the ladder” until Roosevelt might achieve the position Lodge (and others) always pictured for him: the presidency.

In 1888 TR was beginning to settle into the life of a literary gentleman in Oyster Bay, writing books of history and biography (three of the latter were arranged by Lodge). His heart was not in the efforts to stump for Harrison. They were up against incumbent Grover Cleveland, the Democrat candidate, who had made some progress with Civil Service reform during his first term. Cleveland won the popular vote but narrowly lost the electoral vote, thanks to brazen fraud in Harrison's home state of Indiana. (Pennsylvania Senator Matthew S. Quay later said that Harrison would never know “how close a number of men were compelled to approach…the penitentiary to make him President.”) Despite his lack of zeal, TR did campaign for Harrison in New York, in Lodge's Massachusetts, and in the West, where he was already a folk hero for his cowboy life. His books on ranch life and hunting trails, and cowboy articles he wrote for many magazines including the children's literary monthly St. Nicholas, cemented his persona in the public's mind.

After Harrison won the election, Lodge was a frequent caller at the White House, not on his own behalf, but seeking an appointment for Roosevelt in the new administration. Harrison proposed an appointment for him as chairman of the U.S. Civil Service Commission. This was the perfect window-dressing for a president who frankly was indifferent to reforming the federal bureaucracy. TR possibly was the most prominent Republican agitator against corruption and in favor of reform; his appointment, attended by meager support from the White House, would give Harrison cover.

Before long, the president likely felt that he needed cover from Roosevelt himself. True to form, TR made a splash, doing what he could with what he had. The Civil Service Commission, with Roosevelt as its chairman, actually tended to the business, even minute business, of government jobs. It extended the merit system and lobbied Congress to legislate further extensions. TR mediated disputes and reviewed claims of unfair dismissal. He engaged in public disputes with Post Master General John Wanamaker and other prominent Republicans. He frequently called on Harrison at the White House (at that time, even the general public could enter the building and request a meeting with the president), making his case both for reform and for more substantial endorsement of his own reform efforts. Thanks in large part to cartoonists who enjoyed caricaturing the ebullient crusader, as well as the political dust he raised, TR found himself increasingly featured in national cartoons and thus increasingly familiar to the public.

In some ways, the Civil Service Commission years were a golden interlude for TR. He served from 1889 to 1892 under Harrison, and then until 1895 under Grover Cleveland, who asked Roosevelt to remain on the Commission. This meant TR at times had to live apart from his family. He was economically comfortable, but not wealthy enough to move his growing family to Washington. Baby Alice had been joined by siblings Theodore Jr., Kermit, Ethel, and Archie. (Another boy, Quentin, was born subsequent to TR's chairmanship of the Commission.) Roosevelt rented homes for himself in the capital, always in the social and neighborhood orbits of the Lodges. Edith often visited and sometimes stayed for stretches, variously alone or with combinations of the children. Mostly, though, she remained at Sagamore Hill, to which Theodore repaired as often as practical, considering it was six hours away by train.

In a cartoon brilliant in its simplicity, Joseph Keppler of Puck has Uncle Sam looking into the “grandfather's hat” of President Harrison and asking, “Where is he?”

When he was not working, TR's life was a heady time of intellectual stimulation and social bling. He dined out almost every evening, invited by prominent households of literary, governmental, and diplomatic figures. He was a member—usually at the vital center—of cultural salons. And he belonged to the District's most prestigious private clubs, including the Metropolitan Club and the Cosmos Club. John Hay, who had been President Lincoln's private secretary and a friend of TR's father (and would later serve as TR's Secretary of State), frequently hosted gatherings of colorful personalities and stimulating conversation, and TR was a fixture at these events. TR had a harder time cracking the social circle of the brilliant recluse Henry Adams, whose Lafayette Square townhouse across from the White House adjoined the Hays'—but he managed it eventually, and the two became good friends.

Adams was the scion of John and John Quincy Adams, and a respected historian and former diplomat. The invariably icy Adams cast aspersions on Roosevelt's equally eternal ebullience, but he also respected the young man. He once remarked that TR possessed a characteristic Medieval philosophers ascribed to God Himself—“pure act.” The author of the monumental books Mount St-Michel and Chartres and The Education of Henry Adams emerged into the sunshine to call on the White House when Roosevelt's term expired in 1909, and said, with tears in his eyes, “I shall miss you very much,” and then returned to his townhouse. As with his best friend Hay, Adams maintained an open door to TR at his own salons. Other regulars in the movable feasts of clever conversation and intellectual exchanges of the era were Henry Cabot Lodge, Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed of Maine, British diplomat Cecil Spring-Rice, and German diplomat Speck von Sternberg. British author Rudyard Kipling, who made the Cosmos Club his pied-á-terre on his visits to America, painted a fair portrait of the salons, and of the role TR played in the Washington scene despite his relatively minor status in government at the time: “[TR] would come and pour out projects, discussions of men and politics, criticisms of books, in a swift and full-volumed stream, tremendously emphatic and enlivened by bursts of humor…. I curled up on the seat opposite and listened and wondered, until the universe seemed to be spinning —round, and Theodore was the spinner.”

During his six years at the Commission, TR made headway against the hydra-headed spoils system, despite the glacial size and glacial speed of reform efforts. His severest critics, ironically, were not just the entrenched interests of corruption, but also his fellow impatient reformers. The latter included publishers and “professional goo-goos,” a shorthand for “good-government” theorists who never got their hands dirty in the actual work of reform. These putative but unreliable allies were the bane of Roosevelt's battles throughout his career. He dubbed them “the lunatic fringe.”

Cartoonists, whose attitude to Civil-Service reform was generally supportive, even if they drew for fiercely partisan journals, further raised Roosevelt's public profile as they depicted his challenges and actions. The most cynical comments against TR were that Harrison would allow him to reform the civil service just so much. Indeed, that was

Harrison's intention, but TR was prone to wriggle free of the presidential leash. The cartoonists and the public alike relished the dust-ups surrounding the independent-minded Roosevelt.

Somehow during these years, TR continued to find time to write articles and books. He completed a monumental four-volume history The Winning of the West. He also wrote The Wilderness Hunter, a companion to his earlier Hunting Trips of a Ranchman and Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail. He co-authored a book with Henry Cabot Lodge entitled Hero Tales from American History, and he wrote New York, a history of his birthplace and his family's ancestral city.

In 1894, Roosevelt returned to New York City to join in reform efforts that had begun under newly elected mayor, Republican William L. Strong. Strong was elected on a Fusion ticket, as another of the periodic reform waves washed over the city. He had an ambitious agenda to improve the city, which was preparing to merge with Brooklyn to become Greater New York. To address the improvements in the quality of life, he appointed Colonel George Waring as Streets Commissioner. Waring, who had directed the drainage of Central Park for its designer Frederick Law Olmstead and had helped invent the modern toilet device, organized military-style battalions of “white wings”—uniformed sanitation workers who maintained the city streets, garbage removal, and sewer systems.

Along with sanitation, Strong focused on reforming the public safety of New York City. He persuaded Theodore Roosevelt to join the Police Board. TR became the board's president with the goal of cleaning out the Mulberry Street Police Department headquarters. In many ways TR's task was more daunting than the challenges of the federal civil service. Corruption in police ranks was ubiquitous; the public had become resigned if not inured to the system of payoffs, paybacks, and extortion. The corruption of the police force demoralized some officers, but it attracted others. Recruits were largely drawn from the city's population of impoverished Irish immigrants. It was an open secret how much money recruits were expected to cough up in order to be accepted into the police academy, and, further up the line, how much money it cost to receive promotions. Merchants paid policemen for protection, and police “supervised” local elections, especially when Tammany Hall needed votes. Police were the bagmen for politicians, and in many cases protected those who broke the law. For instance, rather than enforce Sunday “closing laws,” they actually protected saloons that operated on Sundays in contravention of statutes.

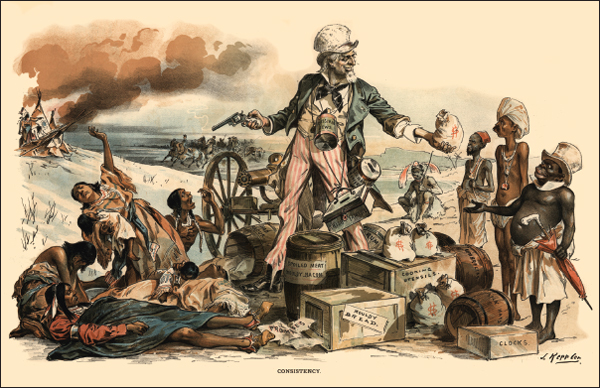

The American frontier unofficially closed between 1889's Oklahoma Land Rush and 1893, when historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared it so, and analyzed the role of the frontier on America's psyche. One ongoing aspect was the “Indian problem,” depicted by Joseph Keppler as one of savage inconsistency (Puck, 1890). Indian wars were virtually the only activity of the Army between the Civil War and the Spanish-American War.

Such was Roosevelt's challenge, or rather the challenging tip of the iceberg. Policemen and the civic establishment both resisted any “reform” of the status quo. Most of the city's press was likewise hostile to any changes, invariably pandering both to merchants and the immigrant class. In addition, newspapers themselves profited from a cozy system of protection: there were more than a dozen newspapers in New York at the time, and vital distribution was carried out by newsboys and newsstands, whose livelihoods were achieved and maintained by strong-arm tactics and the collusion of cops. Finally, the four-member police board consisted of one weak ally of TR and two invariably hostile opponents.

TR refused to be checkmated, however, and went above the heads of the establishment to the people. He enlisted the aid of newspaper reporters and cartoonists, preaching from the “bully pulpit” of his circumstance. This tactic of circumventing the establishment altogether would become a hallmark of TR's career in politics, a strategy begun in Assembly years that he would perfect during his presidency.

During this time, TR developed what would become a lifelong friendship with Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant who recently had written an exposé of poverty in Lower Manhattan, How the Other Half Lives. In this book, Riis drew the public's attention to the same conditions TR had discovered and acted upon in his early Assembly days. There was now an entire class of reporters who took interest in the problems of the urban poor. Some sought simply to fill their sensationalist newspapers, others hoped to write books, still others to turn to “Naturalist” fiction. Among these writers were Lincoln Steffens, Stephen Crane, and Edward W. Townsend. Roosevelt, providing exclusive leads and colorful copy along the way, was featured as a hero in many of their reports.

TR began to roam the streets surreptitiously at night, acquiring the nickname “Haroun al-Roosevelt.” He wanted to check for himself that cops were not sleeping or grafting on the beat. The nickname was inspired by Harun al-Rashid, the pasha of ancient Persia in 1001 Nights who, according to legend, wandered the streets of Baghdad at night disguised as a merchant in order to observe his subjects' activities. More than once the Commissioner was trailed by paid detectives, hoping to discover Roosevelt in a compromising situation. “What? And me going home to my bunnies?” TR asked when he learned of these futile blackmail attempts.

His major battles were over enforcement of the Sunday closing laws. Saloons were closed on Sundays, which disappointed many immigrants who worked laborious six-day weeks and embraced Sunday as their only day of relaxation. TR insisted that he was not leading a prohibitionist crusade. He pointed to laws that were on the books, and suggested that anyone who objected to closing saloons on the Sabbath should talk to their legislators, not the police whose sworn duty it was to enforce the law. There were upwards of fifteen thousand saloons and restaurants and even bawdy houses in New York at the time, and many flouted the closing laws—a convenient situation all around for a system that thrived on bribery and corruption. What made the entire issue sticky was that pious legislators also compelled the closure of museums and art galleries on the Sabbath. Commissioner Roosevelt became the target of people whose wrath should have been directed at those who drafted the laws he was sworn to enforce.

An interesting incident of Roosevelt's tenure as Police Commissioner was his handling of a rally organized by a notorious European anti-Semite named Hermann Ahlwardt. Visiting New York City, Ahlwardt planned a speech designed to incite antagonism against Jews, and he requested police protection. There were contrary appeals to the Commissioner to prevent the rallies. “Of course I told them I could not—that the right of free speech must be maintained unless he incited them to riot,” Roosevelt later wrote. “On thinking it over, however, it occurred to me that there was one way in which I could undo most of the mischief he was trying to do.” Roosevelt detailed a Jewish police sergeant and “a score or two” of Jewish policemen to the event. To avoid making the demagogue a martyr, TR “made him look ridiculous.”

As the months wore on, TR's corrupt opponents and some of the city's newspapers, particularly Joseph Pulitzer's World and James Gordon Bennett's Herald, made battling for reform increasingly onerous. But Roosevelt had the personal satisfaction of knowing his was good work well done. Besides, he enjoyed other, palpable forms of satisfaction as well. For one thing, there was an increase in applicants to the police force. Within the ranks, honest cops, previously harassed, personally thanked the Commissioner for imposing higher standards. Roosevelt was personally involved in almost every case of dereliction or corruption in the police force; even the bad apples appreciated their chief delivering harsh sermons, or offering personalized counsel, as he saw the need, case by case. Speaking as a doting parent would, TR later filled his autobiography's pertinent chapter with story after story of individual cops who were recognized, awarded, or redeemed, and some who earned the Commissioner's devotion despite political pressures.

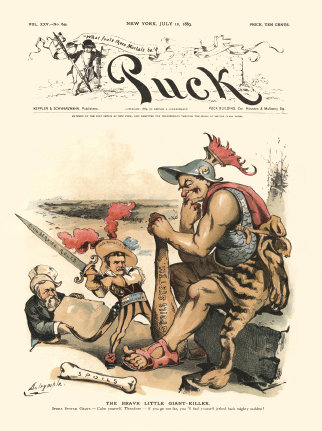

The 1896 quadrennial campaign presented another diversion. Lodge did not need to persuade Roosevelt to enlist in this presidential canvass. Much of the brooding unrest in the nation, incipient revolts that he sought to forestall by reform proposals, boiled over in 1896. The immediate causes of unrest included the crippling Depression of 1893–1894, and attendant veterans' marches and labor strikes. Several of these labor actions, including the Homestead and Pullman actions, were bloody. One “leg” of the stool that represented labor unrest was the economic woes of farmers, which dated back to the formation of the Grange and the Greenback movement of the 1870s. Many western farmers had come to see Wall Street as their enemy. The bloody Haymarket riot that followed an incendiary protest by community organizers of Chicago in 1886 further polarized society. And in the early —90s, these protests coalesced, loosely but in great aggregate numbers, in the formation of the People's Party—the Populists. The party fielded a presidential ticket that polled considerable support in 1892, led by a ragtag corps of radicals from anarchist sympathizers to urban socialists to agrarian reformers. Mary Ellen Lease of Kansas provided one of the movement's memorable slogans: “We need to raise less corn and more hell!” A national economic depression in 1893 further exacerbated the radicalization of lower classes and working groups.

Many malcontents gathered under the Democrat umbrella, although the Populists still hoped to be a viable third party. The Democrat Party's embrace of the issue of free coinage of silver, to be an additional medium of exchange at a fixed rate against gold (a latter-day Greenback movement to inflate the currency and thereby ease farmers' debts) sparked a veritable revolution in American politics. Republicans and Democrats had never been divided on strict party lines over the issue of silver. But now a congressman, barely old enough to serve as president according to the Constitution, delivered an electrifying speech to the 1896 Democrat convention. William Jennings Bryan, of stentorian voice and arresting manner, the “Boy Orator of the Platte,” was a prairie David aiming at the Wall Street Goliath. He seemed to summarize every complaint and irritation of a generation's immigrants, factory hands, mine workers, and poor farmers. He finished his powerful speech with these famous words:

There are two ideas of government. There are those who believe that if you just legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, that their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous their prosperity will find its way up and through every class that rests upon it.

You come to us and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard. I tell you that the great cities rest upon these broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.

If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we shall fight them to the uttermost, having behind us the producing masses of the nation and the world. Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!

Bryan was nominated in a frenzy, and a platform was adopted that contained many propositions that are standard today, but were widely seen as dangerously radical at the time, such as a federal income tax. The Populists endorsed Bryan, and then withered and died as a third-party movement. Most major Democrat newspapers, and many major Democrat office-holders including the incumbent President Cleveland, refused to endorse Bryan. Cartoonists led the charge in forcefully opposing Bryan, drawing countless images of revolutionary crowds, bloody vandals, red flags of communism, and riots, all led by a young Bryan with a crazed expression, under invariably stormy skies. The normally Democrat cartoonists of Puck, Life, The New York World, and The New York Herald changed sides and attacked Bryan.

The subtext of Roosevelt's career from its earliest battles—that reform is a righteous necessity in many areas, but also an antidote to revolution—was now proven in reality. Always the champion of order, TR saw Bryanism, with its purported tendency to outright revolution, as a threat, not a platform. He offered his services to the Republican National Committee. His name already excited interest in sections of America itching for reform, such as New York and Boston, and especially in the West, which considered him one of its own. Besides, the exuberant TR made scores of appearances, sometimes even in front of hostile, radical crowds. This served to augment the “front porch” campaign of GOP nominee William McKinley, who waited for potential voters to travel to the front lawn of his Canton, Ohio, home, to see him. Roosevelt's method made its mark.

By November, not enough of the nation was persuaded to accept Bryan's theses and march into the unknown with him. The Republicans scored a historic victory, despite their genuine insecurity during the campaign. Within a few months, prosperity roared back, probably the result of normal economic cycles, but possibly kick-started by an authentic sense of stability that followed the elections. The American people felt that political demons had been exorcised from the body politic. President-elect McKinley trumpeted the gold standard (about which, ironically, he had been agnostic earlier in the decade), high tariffs, and traditional Republican dogma. The nation breathed a sigh of relief, and even many Democrat journals and cartoonists were happy to celebrate a long honeymoon with the GOP.

One Republican, however, was still anxious, contacting the president-elect constantly. Henry Cabot Lodge was concerned for the career of his friend and protégé Theodore Roosevelt. Lodge was now a Massachusetts senator, with more heft behind his importuning. TR was eager, too, for the right position in the new administration, but deferred to Lodge's lobbying. But McKinley was not forthcoming with a position. During TR's Civil Service Commission days, which had overlapped McKinley's congressional tenure (when McKinley sponsored the controversial, eponymous tariff act), the two men had not been particularly cordial. It did not help matters that McKinley's mentor, Ohio businessman Mark Hanna, had a thinly concealed contempt for TR. And if TR's behavior in his earlier position under President Harrison was any indication of what McKinley could expect, perhaps the new president thought it best not to go there.

Eventually, though, Roosevelt did receive an appointment: Assistant Secretary of the Navy, to serve under John Davis Long, former governor of Massachusetts. It is likely that Roosevelt was appointed for his knowledge of all things naval—his first national recognition had been for his classic study, The Naval War of 1812. Besides, he maintained an interest in, if not an obsession with, the American seaborne military. TR and Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan were mutual admirers. The admiral's book, The Influence of Sea Power on History, had already affected several countries' strategic planning, and Roosevelt hoped to see similar effects in the United States Navy as well. But he received a hint along with his appointment: he was to be the assistant secretary, serving under Secretary Long; and McKinley would be the president. TR's tendency to enact reforms (as well as nearly anything else) with gusto preceded him.

He accepted the appointment and dove into the job with—naturally—more enthusiasm than was required or, probably, expected. Just as other men hum a tune or check their watches, Assistant Secretary Roosevelt was constantly active; he brought research materials to his desk and took charts and graphs home for evening study. He brainstormed with countless experts about ships and armaments and naval technology and international politics. He mapped out innumerable contingency plans—what to do in the event of war with Spain, Germany, England, or Japan; the effect the lack of an isthmian canal had on merchant commerce or military necessities; the lessons of history, and the possibilities for the coming American century—all, roughly, during his first week on the job.

Never busy enough, while he sank his teeth into his new job and managed the exigencies of a growing family—his sixth and last child, Quentin, was born in 1897—Roosevelt also published one more book. It was titled American Ideals, a collection of his articles and speeches about various topics, united by the theme of practical idealism. American Ideals is notable in that material he reprinted from the early 1880s differed little from his strong opinions of 1897, which were identical to positions held at the end of his life. Roosevelt was the picture of consistency, an organic thinker. “It is not difficult to be virtuous in a cloistered and negative way,” he wrote in the preface. “Neither is it difficult to succeed, after a fashion, in active life, if one is content to disregard the considerations which bind honorable and upright men. But it is by no means easy to combine honesty and efficiency; and yet it is absolutely necessary, in order to do any work really worth doing.” That was his credo.

Roosevelt was made to understand that his work in the Navy Department should be limited to his position as assistant, but the rising star was already proving himself capable of much more. Theodore Roosevelt had a vision for America's future that was clear and confident. And—as he demonstrated through his writings—it was a vision he could share forcefully and articulately with the American people.

1889-1897: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

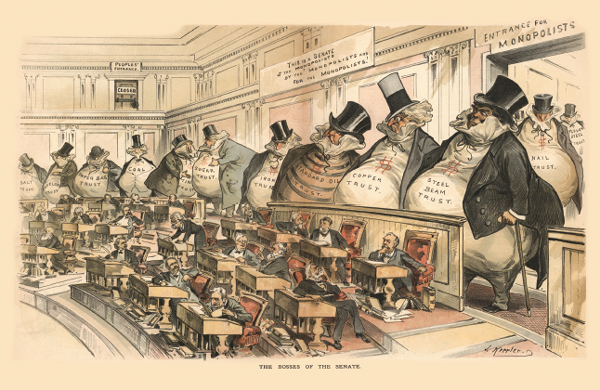

THE POWER OF MONOPOLISTS

The nexus of America's booming Industrial Revolution was the government's policy of “protecting infant industries” through tariffs and other favors. The system also nurtured a crony culture of corporate “donations” to legislators. At the time, the Constitution mandated the election of senators by pliable state legislatures. Here the monopolies (“trusts”) are depicted in the gallery overlooking the United States Senate. Joseph Keppler, Puck, 1889.

1889-1897: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

CIVIL SERVICE REFORM

Puck cynically predicted that President Harrison (in his “grandfather's hat” at rear) would let his young Civil Service Commissioner go only so far in his reform crusades. Cartoon by Louis

Dalrymple, 1889.

Almost exactly ten years after his father's humiliating treatment as a pawn in New York's political wars, TR was named United States Civil Service Commissioner. Over the course of that decade, matters of political corruption had marginally improved. President Cleveland had been a creditable fighter for reform of the civil service and honesty in government. Incoming President Benjamin Harrison desired at least to be seen as an advocate of civil-service reform, even if he wasn't all that devoted to the cause in actuality.

So the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt seemed like a perfect political move. Harrison ought to have realized, however, even so early in Roosevelt's career, that he had added a determined, headstrong crusader to his administration. TR found himself embroiled in many fights with members of Harrison's very cabinet. John Wanamaker, the famous dry-goods merchant and pious Sunday school teacher, was Postmaster General, and he pursued an aggressive policy of firing Democrats and giving jobs to “deserving” Republicans. Harrison's Commissioner of Pensions, Corporal James Tanner, practically raided the federal treasury to dispense jobs and largesse to members of the Grand Army of the Republic, the veteran's group. Roosevelt held interminable hearings and traveled around America to interview aggrieved officeholders and mediate conflicts. He drew up new regulations and then had to fight the inertia of congressional traditions to see them enacted. And he fought bogus charges against his own integrity all the while.

DRAW YOUR OWN CONCLUSIONS

When Stanley carried the first steamboat up the Congo, the natives ran along the banks, yelling with rage, and striving to check his progress by throwing stones and other missiles. Mr. Stanely got there, just the same.

Stories of New York Herald reporter Henry Stanley in “darkest Africa” were enthralling the public. Louis Dalrymple of Puck cast Roosevelt as Stanley, and recalled the story of the first steamship that natives on the shorelines ever witnessed. In the image, various politicians—mostly Republicans—are scattering on the shore at the sight of an ironclad. And the young Civil Service Commissioner, Theodore Roosevelt, is depicted on board, “getting there just the same.”

Roosevelt appeared in three major cartoons in Puck, in 1889, during the very first months of the new Harrison administration. He was obviously creating a stir from a relatively minor post in government, and reform publications like Puck noticed. It is noteworthy, too, that TR's fellow commissioners are clad in frock coats and top hats—probably his actual wardrobe too—while TR is depicted in cowboy hat and boots. His reputation as a rancher and cowboy preceded him.

It never hurts a public figure to come ready-made, so to speak, with one's own icons. President Harrison is the flippant figure atop the elephant. Cartoonist Dalrymple shows the “Republican Press” as muzzled because Harrison appointed many publishers and editors to government and diplomatic posts.

1889-1897: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

AMERICA IN THE GAY NINETIES

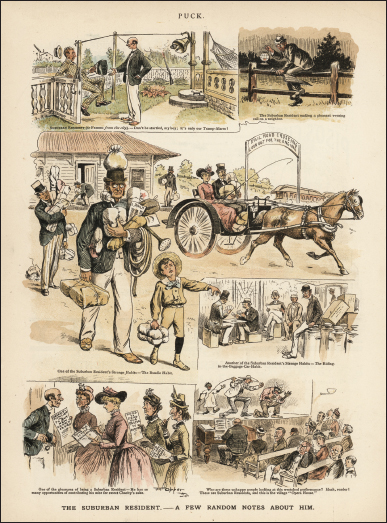

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, a rising middle class moved from urban areas to suburbs and “rural” areas like Brooklyn and northern New Jersey, undertaking the lifestyles immortalized by cartoonists like F. Opper in Puck. His “Suburban Resident” series ran sporadically for years. This example is from 1891. These gentle comments resonated with readers, but there was more empathy than ridicule: Opper moved to the suburbs, as did two authors of the Nineties known for their suburban themes: H. C. Bunner (The Runaway Browns) and Frank Stockton (Rudder Grange).

America's move to suburban towns—whence exurbs would commute to cities—or fashionable but often inconvenient rural getaways in summer months, were hallmarks of the Nineties.

Another cartoon by Frederick Burr Opper about lifestyle disparities between urban and rural Americans. From Puck.

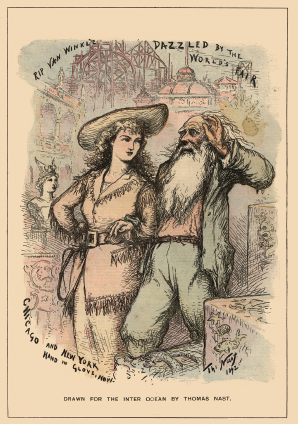

The Chicago World's Fair—technically, the World's Columbian Exposition, marking the 500th anniversary of Columbus' voyage—was an astounding event. Its many visitors saw national displays, technological marvels, and a virtual city of snow-white architectural elegance reflecting the artistic trends of the day. They saw the naughty Little Egypt dance, and a pavilion built by Puck magazine, with artists working and presses rolling, right before the public's eyes. The leading local newspaper, the Chicago Inter-Ocean, introduced the novelty of color newspaper printing to the industry. One of their artists was Thomas Nast, cartooning icon of the 1870s, pioneer of a new phase in cartoon history.

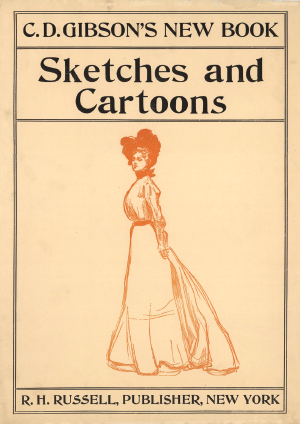

“The Gibson Girl” was the creation of cartoonist Charles Dana Gibson in Life magazine. A spokeswomen for her era, she was independent, assertive, beautiful, and fashionable. American women wanted to look like her, and American men wanted to look like the square-jawed, clean-shaven, toned Gibson man. The Gibson Girl inspired plays, songs, prints, ceramic ware, and reprint books. Above, a poster for a Gibson book of the prestigious art publisher Robert Howard Russell.

1889-1897: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVED

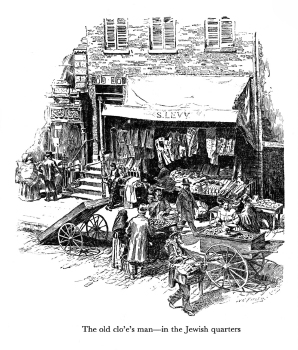

Two illustrations from Jacob Riis's seminal How the Other Half Lives, based on hundreds of photographs Riis took in New York's slums and ghettos.

The Danish-born Riis first took his camera to poverty-stricken areas of Manhattan's Lower East Side, like the Jewish ghetto of Chatham Square, and dangerous neighborhoods like Five Corners, in order to illustrate his points in lectures at churches, and in magazine articles. As his photographs attracted attention, they became the basis also of books. Riis became a founding father of photo-journalism. In his book, because reproduction of photographs was still in its infancy, many shots were re-drawn by illustrators. One of them, Thomas Fogarty, was a teacher of Norman Rockwell.

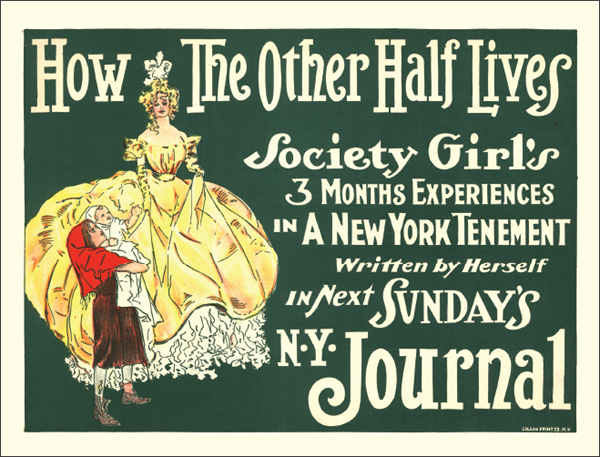

A poster for a Nellie Bly-type series of articles of William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal, ca. 1900. This was not Jacob Riis's own series, but the appropriation of his title illustrates how open the public was to previously taboo subjects like urban poverty and social injustice.

Sensationalist or “yellow” journalism appealed to the curious, sympathetic, and possibly the prurient among readers, and was engaged in primarily to sell newspapers. But it cannot be denied that yellow journalism, like Naturalism in literature or Expressionism in art, helped to awaken the public's conscience to many social ills.

1889-1897: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

POLICE COMMISSIONER

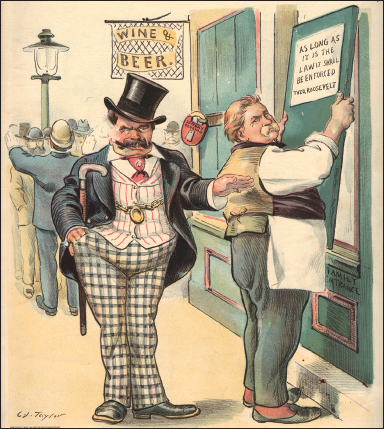

A RATIONAL LAW, OR —TAMMANY.

Tammany. – Goin' to wait till dem reformers repeal dat law, are yer? Put me back and you won't need no repeal! See?

The dilemma of tavern owners, pictured by Charles Jay Taylor in Puck, 1895. The owners were caught between the forces of families looking for Sunday relaxation, the liquor trade, the temperance movement, politicians and some policemen engaging in extortion on the one hand, and Police Commissioner Roosevelt, determined to enforce the law, on the other.

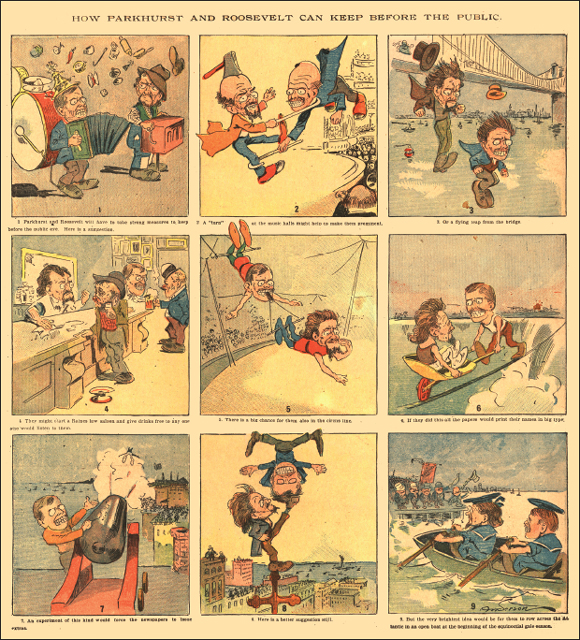

Opponents of municipal reform, such as Pulitzer's New York World, often attacked TR as being a publicity hound rather than a dedicated crusader. In this 1896 cartoon he is paired with fellow reformer and clergyman Dr. Charles Parkhurst. The image was drawn by cartoonist Carl Anderson who, decades later, created the cartoon icon Henry.

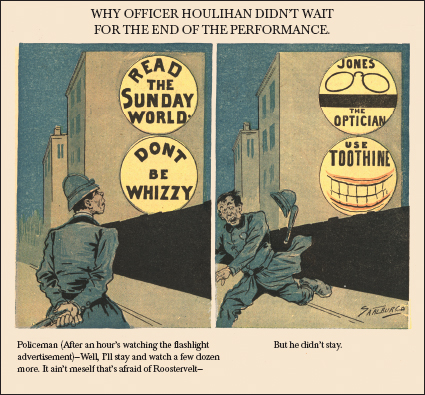

LEFT: In the 1890s, advertisements were projected by “magic lanterns” onto the sides of city buildings. Here a visual pun plays upon TR's already familiar glasses and toothy grin. The cop on his night beat runs because Commissioner Roosevelt was famous for hitting the streets at night, checking on patrolmen.

The cartoonist was Charles Saalburg, creator of the pioneer comic-strip characters the Ting-Ling kids.

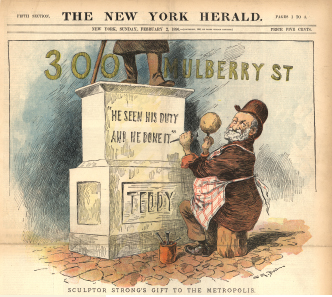

RIGHT: Despite frequent attacks on Commissioner Roosevelt's enforcement of closing laws, The New York Herald paid tribute to TR at the end of his term. This cartoon shows Mayor William Strong engraving a message of gratitude on the Commissioner's statue. (300 Mulberry Street was the headquarters of the Police Department, near the infamous Five Corners in lower Manhattan.)

The cartoonist was Charles Green Bush, regarded at this time as the Dean of newspaper cartoonists but, sadly, forgotten today.

1889-1897: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

POPULISM AND THE 1896 CAMPAI GN

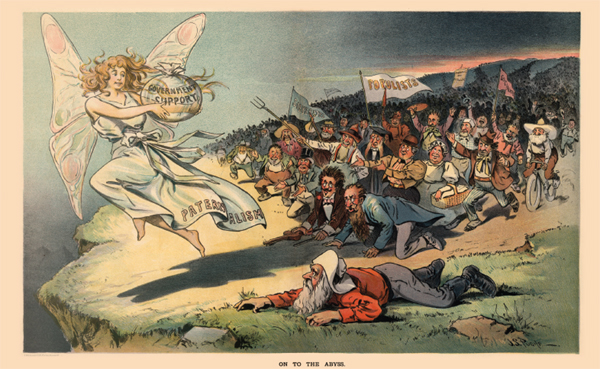

Marxian theories were frequently promoted in America after the Civil War. From fringe “Utopian” and “Communistic” experimental communities, to economic theorists like Henry George and Ignatius Donnelly, from radical immigrant groups to Socialist farmer and labor movements, the Populist Party in the early 1890s seemed to provide an umbrella for all the disaffected and the visionaries. This Puck cartoon by J. S. Pughe labeled the will-o—-the-wisp, appropriately, “Paternalism.” Slight changes to the banners and fashions of the crowd Pughe depicts, and this cartoon would be pertinent today.

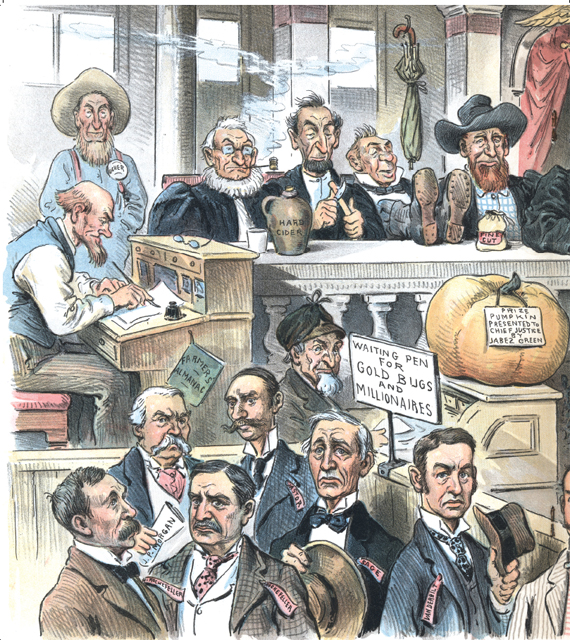

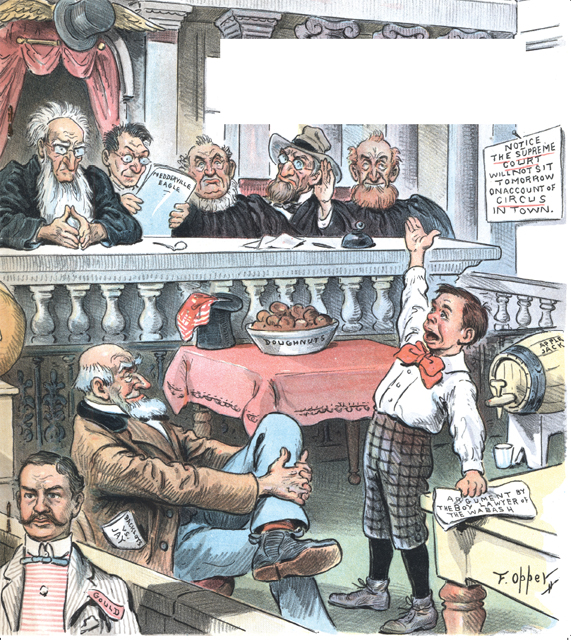

Cartoonist Frederick Burr Opper aimed wide with this satirical forecast of the Supreme Court under a Populist United States. Rubes and hayseeds on the bench represent the Populist base, and the youngster arguing his case represents William Jennings Bryan, who was barely over the constitutional minimum age when he ran for president. Opper (1857–1937) produced cartoon masterpieces of this caliber for more than half a century; this, for Puck, 1896.

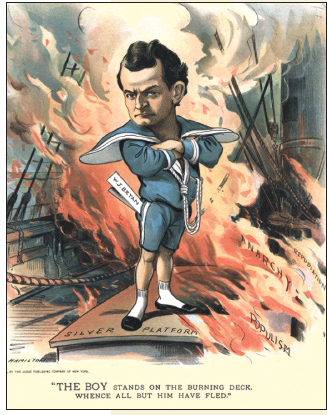

There were few cartoons of William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 campaign that did not feature flames of anarchy, storm clouds, or menacing mobs. This Grant Hamilton portrait of the young Bryan graced a front cover of Judge.

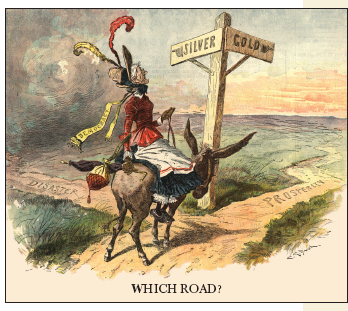

The fork in the road confronts the Democrat Party in this C. G. Bush cartoon from The New York Herald, 1895. In truth, however, the “silver agitation”—to put America on a two-metal economy instead of the (now long abandoned) gold standard—was a national, not a strict party, issue. The “Gold Standard Nominee” in 1896, Republican William McKinley, had flirted with the free coinage of silver a few years previously.