THE SPLENDID LITTLE WAR

W. A. Rogers, a news sketch artist who drew cartoons, story illustrations, and news drawings for Harper's Weekly, visited Washington in February 1898. The United States Navy was embroiled in a crisis in the aftermath of the February 15 explosion of the U.S. battleship Maine in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, where it had been dispatched to protect Americans during upheavals in that city. Two hundred sixty-six sailors had been killed in the blast. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt, true to his character, had become heavily involved in the U.S. response to this disaster. Rogers sketched TR leaning against his desk, deep in thought and reading a dispatch, amidst diplomatic reports and visitors. It is likely that Rogers' scene depicts one of the few quieter moments in that office in the first months of 1898.

To this day, the cause of the Maine's explosion is a matter of dispute; but at that time, many Americans assumed the Spaniards had provoked and committed the act. The Spanish monarchy had suppressed many revolutions and stifled widespread discontent throughout its four-century rule of Cuba. The oppression often caught the attention and the sympathy of Americans, some of whom envisioned the annexation of Cuba, while others were sincerely moved to urge humanitarian intervention. Spain's empire had begun to creak from old age and poverty, and its policies—for instance, herding numerous subjects of its colonies into “reconcentration camps”—grew more brutal.

In earlier decades, some Americans had had particular reason to keep their eyes on Cuba. The antebellum South, for instance, sought new slave states. Likewise, agricultural trusts and monopolies had a particular interest in the island. Meanwhile, Cuban revolutionaries grew ever bolder, provoking major Spanish military intervention every decade since the 1860s.

Assistant Secretary Roosevelt's office, while it was always a lively center of activity (especially when Secretary of the Navy

John D. Long was away—which was often), was particularly busy on the day W. A. Rogers came to sketch it. TR's office was also the nerve-center of the “war party” in Washington, comprised of those who thought that Cuba should be liberated from Spanish rule. They believed that it was the duty of the United States to become a world power, sweeping away the mossy vestige of European colonialism from the hemisphere, and expanding America's real estate.

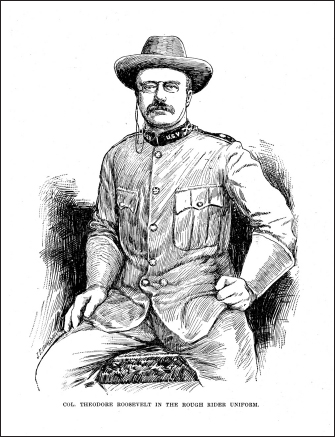

Many newspapers and magazines covered America's shortest war exhaustively. This portrait of Colonel Roosevelt is from a book published by the Chicago Record-Herald. The New York Journal published a long part-series. Reporters Edward Marshall and Burr McIntosh wrote illustrated histories of the little war. Roosevelt, who fought there, and Henry Cabot Lodge, who remained in the Senate, wrote books. Folio volumes overflowing with personal accounts, drawings, paintings, and photographs, were issued by the magazines Harper's Weekly, Leslie's, and Collier's.

Since the Civil War, the ranks of America's armed forces had been at meager levels, and the state of armaments and naval forces were in frightening disarray. This was the view of perfervid disciples of Manifest Destiny like Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt, Admiral Mahan, and senators Albert Beveridge and Henry Cabot Lodge. Among the other proponents of expansion, or at least the adventure promised by a swift, short war (which a war with Spain would be, by general consensus) were sensationalist newspaper publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, whose flagship papers were, respectively, the Journal and the World in New York City.

Big Business was against a war, however. And so was President McKinley, for the same reason: the uncertainties of war could disrupt the economic recovery, which was robust after years of depression and the recent scare of the Populist revolt. A panoply of anti-expansionists, pacifists, and nativists joined ranks to oppose militarism and the conquest of foreign lands and alien peoples. Even the destruction of the Maine had not turned public opinion entirely in favor of war.

Theodore Roosevelt saw war as a legitimate instrument of foreign policy and national purpose—even as a means to inculcate “manly virtues” in a new generation—and his position was well known. His was not an uncommon attitude at that time. TR always frankly discussed war as routine in the life of nations—something that strenuous diplomacy should work to make unnecessary, but a reality that a virile republic should never avoid. The belief was woven into his first major book (The Naval War of 1812), magazine articles, and even his recent address to the Naval War College. As with many of his policies, the codification, “If I must choose between peace and righteousness, I choose righteousness,” was TR's consistent, lifelong credo, not an evolving ideal. So McKinley's nervousness in appointing TR had been reasonable, given the common impression of Roosevelt.

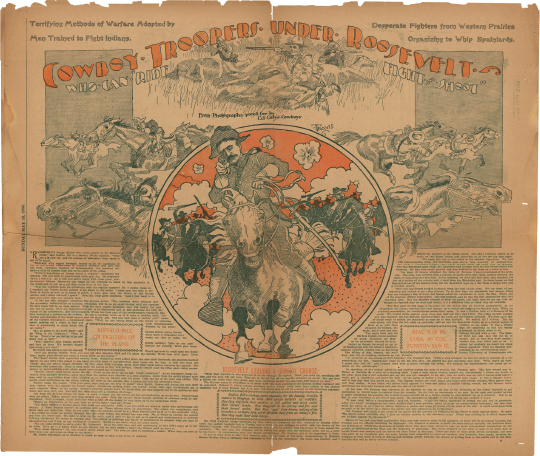

Behind the scenes, TR worked on an initiative that would strengthen the American offensive, should war against Spain become a reality. He recalled the strength a group of his manly cowboys were willing to wield against the Haymarket rioters and bombers in Chicago in 1886. He had envisioned such volunteer action at the time. What if he were to gather those same men into a “democratic posse” of cowboys from the west and brave patriots from the east, to take part in the Cuban struggle? This was an idea he had revived more than once since 1886, under presidents Harrison and Cleveland, despite the fact that war was never a remote possibility in those years. The presidents never had to do more than take Roosevelt's offer under advisement. TR would continue to bring up the idea even after the Spanish-American War and his own presidency, even petitioning President Wilson, unsuccessfully, at the height of his political opposition. Now, at the outset of war with Spain, TR contacted countless willing warriors, drafted organizational charts, and so forth. Significantly, he had never raised such a band of brothers, or proposed doing so, during all the years when the Army was preoccupied with battling American Indians. It was unrest on foreign soil that stirred his martial spirit.

A scene from the battlefield—Roosevelt as detective. He discovers freshly cut barbed wire and concludes that Spanish troops have recently passed. From The Record-Herald.

From his office, and as wide as he was able extend its influence, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt grappled with the possible requirements and contingencies to the nation if war came. Exercising enormous sagacity and brilliant military strategy, TR ordered Commodore George Dewey to move the fleet to Manila, in the Philippines. It is plausible that by doing this he exceeded his authority; he was not authorized to issue such orders, except in the technicality-based provision of the Secretary's incapacity or absence. Secretary of the Navy Long, though not in the office on the day TR cabled Dewey issuing this order, was neither sick nor unreachable; he was merely taking a day of rest. Long chided Roosevelt for this action upon his return to the office, but the deed had been done; Long did not rescind the order.

While TR continued active in his civilian capacity as Assistant Secretary in the Department of the Navy, he was equally busy building his cowboy regiment as a part of the Army. Since the War of 1812, the states had been allowed, even encouraged, to raise volunteer corps. The practice served to mobilize (and democratize) public support of war, which arguably was more important than the supplementation of the regular Army. The volunteer troops also were politically important, allowing prominent politicians and citizens to carry their states' flags, and accommodating the quick integration, and later demobilization, of state guard units. Roosevelt astutely arranged for the First United States Volunteer Cavalry, thereby not restricted to one state. He recognized that this must be a national effort. And he was confident enough to take on a leadership position within his volunteer corps, despite his lack of military experience. The most experience he could boast—besides reading military history and tactics—was service in the New York National Guard, which he had joined on August 1, 1882, commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant of B Company, 8th Regiment. He was eventually promoted to Captain, and he resigned his commission in 1886. All rather too minor, even TR realized, to be relevant to the upcoming duties. TR declined the highest rank of the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry—Colonel—recommending his friend Leonard Wood for the position. Wood was an Army surgeon who served as personal physician to presidents Cleveland and McKinley; his previous service was in American Indian campaigns, during which he had been awarded the Medal of Honor.

The greatest obstacle Roosevelt faced in preparing for service in Cuba, however, was the serious illness of Edith. Diagnosed as near death in the spring of 1898, Edith was recovering at an alarmingly slow pace after an operation following the birth of their last child, Quentin. But recover she did, so TR determined to participate in the war he had advocated for so strongly—to “pay with his body for his soul's desire,” if need be.

There were two months between the Maine disaster and the actual declaration of war (an Alphonse-Gaston situation where both sides eventually declared that a state of war “already existed”). Spain was decrepit and in no condition to defend its colonies. President McKinley sincerely wished to avoid war, and exhausted all means of diplomacy and patience in his attempts to do so. TR was quoted during this time, characterizing his commander-in-chief as “having the backbone of a chocolate éclair.” Still, in the interim, Roosevelt was able to see to all arrangements for his volunteer regiment. He filtered through thousands of applications, as newspapermen and cartoonists helped spread the word. He ordered custom uniforms for himself from Brooks Brothers, and dozens of extra spectacles. Finally, he resigned as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, in order to take on his new duties as Lieutenant Colonel of the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry. Secretary of the Navy Long told him frankly that besides being a fool and courting death, he was throwing away a promising career in public service. In his diary entry for April 28, 1898, Long wrote of TR: “He thinks he is following his highest ideal, whereas, in fact, as without exception every one of his friends advises him, he is acting like a fool. And, yet, how absurd all this will sound if, by some turn of fortune, he should accomplish some great thing and strike a very high mark.”

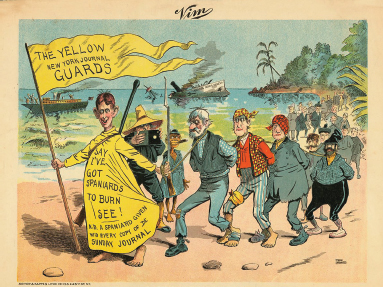

Even the Yellow Kid joined the war fever. This sketch appeared in The New York Journal. Cartoonist R. F. Outcault illustrated a book about the Rough Riders written by the wounded war correspondent Edward Marshall. Outcault's Yellow Kid is regarded as the first comic strip.

The public was quickly warming to the thrill of an American military adventure, and TR's regiment of patriotic citizen-soldiers—comprised of cowboys and playboys, cattle drivers and polo players, men of shady résumés and blueblood pedigrees, “Half-Breeds” and WASPs, from every part of the land—gained almost instant celebrity. Although Leonard Wood was the colonel of this popular regiment and TR only the lieutenant colonel, it was TR who stood out in the public mind. Reporters, cartoonists, and plain folks dubbed the unit “Roosevelt's Rough Riders,” and their affection matched their awe. The Rough Riders were the stuff of legend before they ever set foot in Cuba.

Getting to Cuba proved no small feat, since boats were scarce and logistics chaotic. First, they would need to go to San Antonio, Texas, to train, to become a disciplined fighting force virtually overnight.

TR was acutely aware that this war might be over before he could get his men into it. Straining against this possibility, he managed a whirlwind of contacts, preparations, and personal arrangements at home, for Edith's recovery was fragile. The Rough Riders needed only minimal training in riding and shooting—these men were among the best riders and the best shots in the nation—but they needed to learn discipline, and a strict understanding of the democratic nature of their regiment, where all would be equal in what was offered and expected. Colonel Wood handled the military drills, while Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt addressed the group ethos and camaraderie. And of course, newspapermen and cartoonists kept the Rough Riders' activities squarely in the public eye.

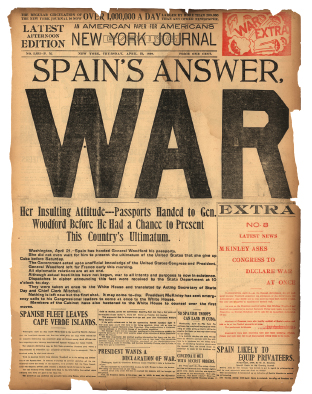

In fact, the press corps flocked to Roosevelt and his Rough Riders. It was the Rough Riders' congenital circumvention of red tape that provided part of its appeal. To the public, the Rough Riders embodied a youthful free spirit that seemed to mirror the American eagle spreading its wings. To the press corps, TR provided reliably good copy, as well as a “friend in court” if they needed favors to do their work, landing scoops or obtaining interviews. Two of the newspapers reliably opposed to Roosevelt and his policies in New York were the Journal and the World; but they were his allies in beating the drums for war. Not every newspaper in America was bellicose—remember, traditional Republicans, business interests, and many Democrats were against a war—but Hearst and Pulitzer eclipsed the other New York papers. War fever (as well as an array of “yellow journalism” features like the popular Yellow Kid cartoon) served to push the circulation of the Journal and the World past a million copies a day. The idea of chasing Spain from the Western hemisphere was beginning to excite American youth and sell newspapers. When war was finally declared, the Journal's headline type was almost as tall as the newsboys who hawked as many as fifteen editions a day on street corners.

Among the reporters and artists who flocked to publicize the activities of the Rough Riders were Richard Harding Davis, Stephen Crane, Edward Marshall, James Creelman, and Burr McIntosh. The pioneer movie-makers J. Stuart Blackton and Albert E. Smith covered the war with primitive motion-picture cameras. The illustrators included news artists like T. Dart Walker and Thure de Thulstrup; military artists like H. A. Ogden and Henry Reuterdahl; society artist Howard Chandler Christy; and, importantly, Frederic Remington.

Remington, the quintessential pictorial chronicler of the American cowboy, was itching for America to wage war in Cuba. After the wild west, the setting and potential action stirred the artist's narrative urges. The illustrator's career had virtually begun with Theodore Roosevelt's cowboy stories. Remington produced almost a hundred drawings for TR's Ranch Life and Hunting Trail, serialized in Century magazine a decade earlier, and the two men were good friends. Waiting impatiently for the war to start, Remington went so far as to produce incendiary drawings (for example, images of humiliated women being strip-searched by Spanish officials), in order to fuel war fever in America. He bemoaned the lack of action to his publisher of the moment, Hearst, who cabled back (at least in legend): “You provide the pictures; I'll provide the war.”

When war came, many of its memorable images—including thrilling and romantic, if not romanticized, iconic paintings of the Rough Riders in action—were provided by Frederic Remington.

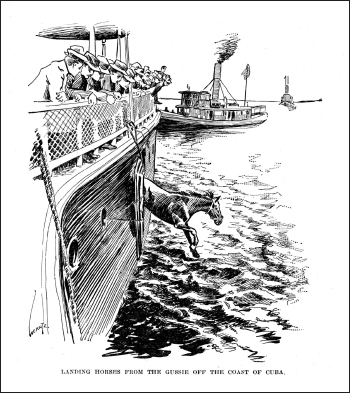

What romantic elements there were in the victory over Spain came with much effort and deadly determination, even before combat began. When the Rough Riders arrived in Tampa for transport to Cuba, there was virtual anarchy—no schedule of what troops would leave, or when, or how. TR and his men displaced other soldiers in their scramble for spaces aboard a troop transport ship, all in their effort just to get to Cuba. Once off Cuban waters, there were no logistics for speedy, practical, or orderly disembarkation. Men jumped and managed to swim with heavy packs; provisions were dumped, and much was lost; horses were pushed, and many drowned. Roosevelt was so angered that he was heard to utter the word “damn” one of the only times in his life. Once they finally got to shore, there was further confusion regarding assignments for camps and plans for the soldiers.

Cuba proved a difficult adjustment for the Americans. Their woolen uniforms were ancient or of ancient design, and not at all suited for tropical weather. This was due to poor tactical considerations from quartermasters back in Washington, who should have been aware of Cuba's heat and humidity. Soldiers also had to contend with yellow fever and rancid canned beef in Army rations. (After the war, the “embalmed beef” scandal would tear through the War Department.) Once soldiers penetrated the dense tropical vegetation, they became the targets of sharpshooting snipers; soldiers were as exposed in the forests as on the open field. Another problem was weaponry. The Spanish were equipped with new German Mausers, repeating rifles that used smokeless gunpowder, a recent invention. American soldiers often had older weapons and old-fashioned gunpowder, which made it impossible for a U.S. soldier to keep his position hidden.

The Rough Riders landed—or rather splashed, trudged, or swam ashore—with troops of the regular Army. Many of the professional soldiers resented the presence, and the notoriety, of these temporary soldiers in hastily assembled volunteer units. On June 22, the Americans gathered in Daiquiri, which was fifteen miles from the Army's main objective, Santiago (on the southern coast of Cuba, west of Guantánamo). Many Spanish troops and the majority of the Spanish fleet were in Santiago and its harbor, a good defensive location due to the harbor's narrow entrance. The Americans marched quickly over roads and hacked through jungle growth to the town of Siboney, where the American base was established. On June 24, they fought their first major battle, at La Guásimas. It was a bloody frontal assault by the Americans, from which the Spanish eventually withdrew toward Santiago. One of the colorful anecdotes of the war arose from this battle. The American general Joe Wheeler had been a Confederate general in the Civil War; his leadership position in the Spanish-American War was a sign that healing was finally beginning from that old fissure in America's national life. Whether old “Fightin'Joe” was nostalgic or just dotty, he yelled as the Spanish retreated, “Come on, boys! We've got the Yankees on the run!”

Many of the American troops in the early action were the Rough Riders under Colonel Wood and Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt; and many of the casualties were theirs also. Indeed, when the war was over, the Rough Riders sustained the highest percentage of loss of any cavalry unit in Cuba. At La Guásimas, Roosevelt's men were joined by the

1st U.S. Regular Cavalry, and the 10th U.S. Regular Cavalry, a unit of black troops nicknamed the Buffalo Soldiers. The performance of the Rough Riders was such in the next few days, and with Generals Wheeler and Young being incapacitated by yellow fever, that Colonel Wood and Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt received field promotions to Brigadier General and Colonel respectively.

While the United States Navy maneuvered to either bottle the Spanish fleet in Santiago Harbor with a scuttled ship or pick it off if it tried to escape, the U.S. Army advanced on the city of Santiago itself. By July 1, the last major obstacles the Americans faced were fortified blockhouses set atop hills overlooking Santiago, known as the San Juan Heights.

What happened in these campaigns is the stuff of legend. Because war correspondents and artists were attracted to Roosevelt like ants to honey, the representatives of the great newspapers and magazines witnessed, and generously chronicled, the action of the Rough Riders at the San Juan Heights. Despite the inevitable embellishment by many of the writers and artists, the glory of the Rough Riders' fighting defied exaggeration: their success was genuine and singular. The written and pictorial embellishments were civilian artists' meager attempts to describe the intangible qualities of bravery and heroism to people back home, and to succeeding generations. The Battle of San Juan Hill was fought from July 1 to 3, just before America's Independence Day in 1898, as if to confirm the battle as a seminal event in American history, not just in the life of Theodore Roosevelt.

At the base of Kettle Hill, which was in front of and to the right of San Juan Hill, TR comprehended the necessity to capture the promontory, and either kill or rout the Spaniards within the hacienda. The enemy was within its fortification, while the Rough Riders were exposed in open field. Because of the problems with transporting troops, disembarkation, and impassable jungles, the Rough Riders had few horses, though Colonel Roosevelt still had his horse, Little Texas. He initially charged up Kettle Hill atop Little Texas, but was impeded by a wire fence. At that point, he let Little Texas free and continued on foot to lead the successful charge of the Rough Riders and other regiments up Kettle Hill. After securing Kettle Hill, Roosevelt saw that those attacking San Juan Hill needed help. He called “Charge!” and began to run down Kettle Hill. Unfortunately, due to the cacophony of gunfire and yelling, only five of his men had heard his order and charged alongside him. After about a hundred yards, he realized that the rest of the troops remained atop Kettle Hill, so he instructed the five with him to stay where they were and he ran back to get the others. After some coaxing and yelling on the Colonel's part, the Rough Riders and the rest of the brigade atop Kettle Hill quickly fell in and charged the San Juan Heights. Only the last-minute scramble of routed Spanish troops from the summit of the San Juan Hill prevented hand-to-hand combat in the blockhouse.

For the rest of his life, Theodore Roosevelt called the charges up these two hills his “crowded hour.” The actions taken by the Rough Riders and the other regiments went by so fast that they even tested Roosevelt's fantastic ability to recall minute details. In his book The Rough Riders, Roosevelt writes that he killed a Spanish soldier from only ten yards away during his charge up San Juan Hill. Yet, in letters written to both Edith and Henry Cabot Lodge only days after the conflict, Roosevelt wrote that this event happened during the initial charge up Kettle Hill.

In fact, the Rough Riders were not alone as they scaled the San Juan Heights. A glorious slice of America—truly the picture of the new nation—comprised the wave of men. Lieutenant John J. Pershing (“Black Jack”), the leader of the Buffalo Soldiers, later wrote: “[T]he entire command moved forward as coolly as though the buzzing of bullets was the humming of bees. White regiments, black regiments, regulars and Rough Riders, representing the young manhood of the North and the South, fought shoulder to shoulder, unmindful of race or color, unmindful of whether commanded by ex-Confederates or not, and mindful of only their common duty as Americans.”

In a few short hours, American soldiers swarmed over the top of San Juan Hill, occupying a piece of land that was to enter the annals of the war, and of American history writ large. The Rough Riders posed for a photograph under the American flag at the top of the hill, a proud, beaming Colonel Roosevelt in the center amidst his comrades, pistol in holster, wearing a sweat-stained shirt and trademark dotted neckerchief, hands on hips, chest out, beaming.

Following this victory, Secretary of the Navy Long would add a post script to his April 28, 1898, diary entry. “Roosevelt was right,” he wrote, “and we his friends were all wrong.”

TR had molded this unit, from conception on paper to assembling men from across the nation, training, and virtually commandeering by squatter's rights a place for them on troop transports. He “pulled no rank,” eating and sleeping with his men, and suffering the same privations, of which there were many. He pulled the Rough Riders together on shore, pushed them through jungles, facing enemy soldiers in the field and snipers in the trees. Sometimes following orders with liberal interpretation, he inspired his men in battle and led the assaults up San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill.

After the victories of San Juan Heights, the Americans had to decide whether or not to attack Santiago. The troops encamped to regroup, and leaders considered the Navy's role. It had unsuccessfully scuttled the USS Merrimac in order to block the harbor entrance…a blessing in disguise for those who sought a more glorious armed victory rather than a siege. After a long standoff, the Spanish fleet made a break for open seas, but was demolished by the awaiting American ships, which sustained only minimal damage.

TR charged up San Juan Hill during those steamy July days in Cuba, not to indulge ambition, but because he considered the American cause one worth fighting and even dying for. In his view, risking all, sacrificing for a cause, and acting on one's convictions, were simply the marks of a man with integrity, and of a nation with character. Through his actions, he intended to do his forebears proud, and to inspire future generations. He attracted and molded the Rough Riders to act in the same way. The Riders' honor roll was lengthy and grim, and as democratic as the regiment itself. Two of its earliest casualties were the Eastern blueblood Hamilton Fish Jr., grandson and namesake of President Grant's Secretary of State, and the charismatic bronco-buster and Arizona sheriff “Bucky” O'Neill, who, moments after telling his comrades that a “Spanish bullet was not made that could kill” him, was felled by a whizzing Mauser bullet through his neck. Another casualty was The New York Journal correspondent Edward Marshall, who was shot in the back and subsequently partially paralyzed. In a display of the camaraderie that prevailed in the Rough Rider “family,” soldiers and non-combatants, correspondents from rival papers wrote or sent Marshall's dispatches for him, shared “scoops,” and generally saved his professional, not just his physical, life.

The Rough Riders were like family, and they would remain so until the last member died decades later. In Roosevelt's political campaigns, veterans would assemble in parades. At his inaugurations, they formed honor guards. A popular song of the day, “A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” somehow became associated with the Rough Riders and therefore Roosevelt; this became a theme song at TR's political rallies for the rest of his life.

Once the Americans had won the Cuban campaign, they naturally wanted to go home. The soldiers were sweltering in the tropical haze. The tainted canned beef supplied by the Army was making them sick, and many were starting to contract yellow fever. More soldiers died of yellow fever, malaria, and dysentery than had died in combat in Cuba. Military professionals in Cuba wanted their men to be allowed to return home, but military bureaucrats in Washington dragged their feet. Now, TR's “temporary” military status proved an asset to the commissioned officers; he implicitly became a sacrificial lamb. At their instigation, TR executed a “round robin” letter, which was dispatched to the Secretary of War, requesting that troops return to American soil. The letter embarrassed the Department when made public. Though written in a committee format, no one was fooled as to its authorship—TR had already been quite vocal on the issue. He got his way—the troops left Cuba. But Army brass were rankled, and TR did not receive the Medal of Honor that he, and millions of American citizens, thought he deserved. The Medal was finally awarded posthumously at a White House ceremony in 2001, making Theodore Roosevelt the only president to receive both the highest American military honor and the world's highest recognition to a peacemaker, the Nobel Peace Prize.

Colonel Theodore Roosevelt's portrait in U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Uniform was everywhere. By Charles Dana Gibson.

The soldiers returned to U.S. soil. After a month of quarantine at Camp Wickoff, on Montauk Point at the top of Long Island, the soldiers were mustered out. The public—including Edith, now fully recovered—was allowed in…with press and cartoonists, of course. Even President McKinley traveled up from Washington and all the way to the eastern point of Long Island to honor the Rough Riders. The biggest honors, however, were exchanged between TR and his men. As the Rough Riders assembled one last time, they made speeches in tribute to their Colonel, and they presented him with a bronze sculpture by Frederic Remington, “The Bronco Buster.”

TR thanked them:

I am proud of this regiment beyond measure. I am proud of it because it is a typical American regiment. The foundation of the regiment was the cowpuncher. No gift could have been so appropriate. The men of the West and Southwest—horseman, rideman, and the herders of cattle—have been the backbone of this regiment, which demonstrates that Uncle Sam has another reserve of fighting men to call upon if necessity arises. Outside of my own immediate family, I shall never show as strong ties as I do toward you. I am more than pleased that you feel the same for me. Boys, I am going to stand here, and I shall esteem it a privilege if each of you will come up here. I want to shake your hands, I want to say goodbye to each of you in person.

Before that happened—few dry eyes among the troops—TR stopped to pay tribute to the black soldiers of the 9th and 10th “Colored cavalry” regiments who were also present. “The Spaniards called them ‘smoked Yankees,’ but we found them to be a very excellent breed of Yankee indeed!” And then, for hours, Rough Riders passed by in file, each one exchanging good-byes and thanks.

After San Juan Hill, John Hay, TR's father's old friend who would sign the peace accords with Spain as Secretary of State, wrote to TR: “It has been a splendid little war, begun with the highest motives, carried on with magnificent intelligence and spirit, favored by that Fortune which loves the brave.” If wars can be splendid, this one certainly was for America. In concert with many other aspects of expansion—population, prosperity, culture, invention—America was on the verge of a splendid new era. It would be called The American Century.

And Theodore Roosevelt was poised to lead that charge, too.

1897-1898: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE GOLDEN AGE OF

YELLOW JOURNALISM

CAPTURED BY THE YELLOW KID.

“While William Hemment photographed the wreck I scanned the shore for Spaniards, and finally saw some score of figures huddled together in one corner of the beach. We shouted to them and made a demonstration with our firearms, and the poor, cowed fellows, with great alacrity, waved a white handkerchief or shirt in token of surrender.”

“I sent our small boat for the ship's launch, first having landed Mr. Hemmett and his assistant. We three stood guard over our wretched Spaniards until the launch arrived.”

—Telegram in N. Y. Journal, from W. R. Hearst at Santiago.

Because an early pawn in their circulation wars was R. F. Outcault's cartoon character the Yellow Kid, for years Pulitzer and Hearst were referred to, and depicted, by detractors as yellow kids in nightshirts. (The character is generally believed to have given rise to the term “yellow journalism.”) Some of those critical cartoons were drawn by Leon Barritt for the short-lived color cartoon paper Vim.

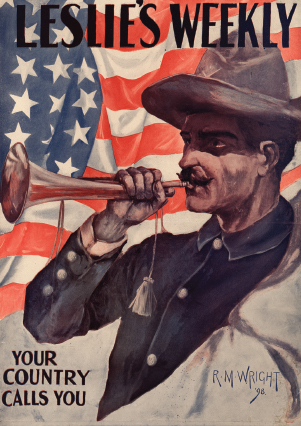

LEFT: Even today this would be a startling newspaper headline. But in the staid nineteenth century, when color and artwork were new things in newspapers, headlines such as this attracted readers like never before. Hearst's Journal sometimes printed sixteen editions a day (most of the changes being updates in the front pages, and bulletins), with newsboys hawking, “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!”

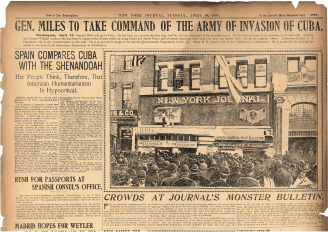

BELOW: In addition to screaming headlines and screaming newsboys, the Journal delivered news in two other unique ways: at night it projected war headlines onto the sides of buildings by magic lanterns. This method had been used by papers on election nights since the 1880s, but during the Cuban War fever, as this illustration shows, Hearst devised an enormous frame on the front of his Park Row headquarters, opposite City Hall, and put a cartoonist on scaffolding. He lettered the latest news, and made drawings, portraits, and cartoons of breaking news. Huge crowds gathered to watch.

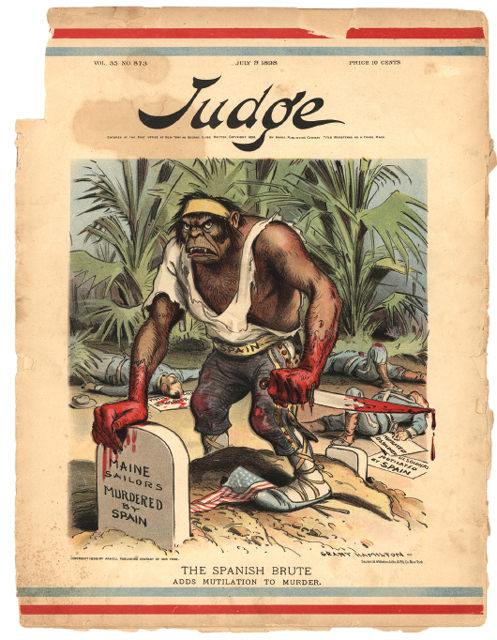

A provocative cover cartoon by Grant Hamilton that appeared a week after the Rough Riders' charge up San Juan Hill.

1897-1898: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

AMERICA AND CUBA

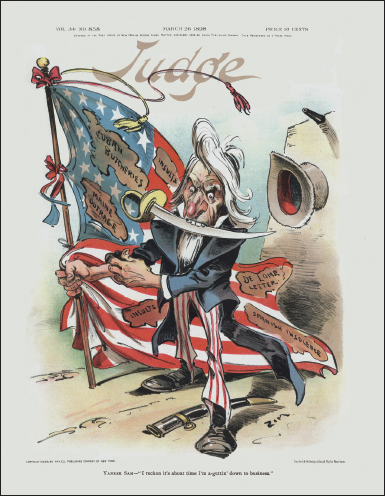

The cover of Judge magazine from March 26, 1898, a relic of the days when, some might say, Uncle Sam was capable of outrage over human rights violations in Cuba and slights against the American flag. The cartoonist was Eugene Zimmerman (“Zim”).

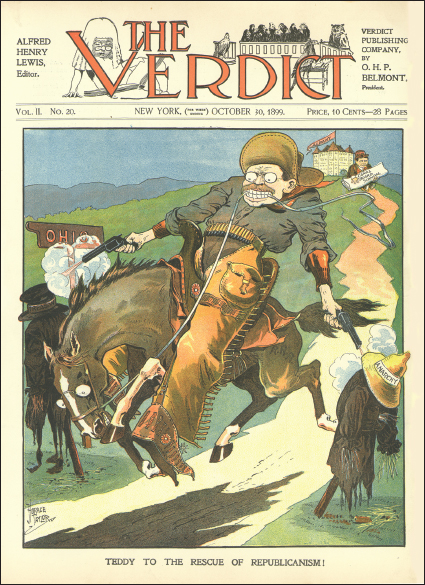

T.R.'s military celebrity changed the flavor of national politics. Grant Hamilton's commentary in Judge, 1898.

1897-1898: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE ROMANTIC ROUGH RIDERS

A war likely to be of short duration, a nation hungry for dashing heroes, a colorful adventurer like Theodore Roosevelt, and a press corps of writers and artists happy to attract readers with instant legends. The combination resulted in countless images of the romantic Rough Riders. Below, in The New York Herald; above right, The New York World; opposite below, a painting by W. G. Read that graced many posters and postcards.

1897-1898: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE REALIST IC ROUGH RIDERS

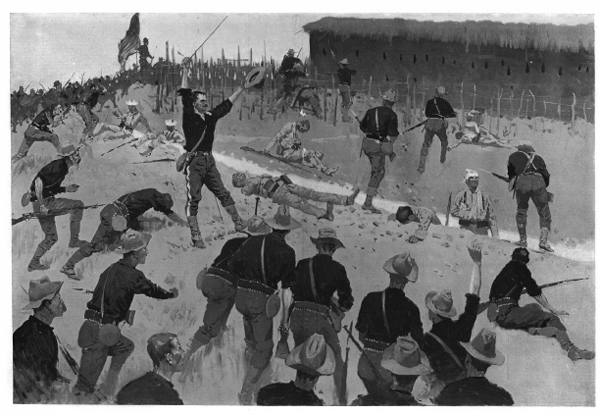

THE STORMING OF SAN JUAN'THE HEAD OF THE CHARGE'sANTIAGO DE CUBA, JULY 1.

Drawn by Frederic Remington, Special Artist for “Harper's Weekly” with General Shafter's Army.

Not a dashing cavalry charge, but the brilliant Frederick Remington managed to make a desperate scramble up a hardscrabble hill seem romantic. It seems a forgotten fact that Remington drew and painted a great number of Army subjects, mostly in the American West. It was natural that he depicted Rough Rider Roosevelt's exploits, and helped create a popular legend. Some of his first work was illustrating TR's cowboy articles and books. This painting appeared in Harper's Weekly.

Howard Chandler Christy's painting from Truth magazine. It is ironic that Christy, an illustrator famous for high-society themes and glamorous women, would depict the war in such paintings. Not, that is, that he covered the war—it seemed that every illustrator, cartoonist, and reporter in America had gone to Cuba—but that

he eschewed the glamorous aspect of the war and captured the nitty-gritty.

1889-1897: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE END OF THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

On the day the battle for San Juan Hill commenced, Judge opined that Uncle Sam had learned his lesson about preparedness. A large part of the Cuban campaign was fought and won by volunteer regiments (with disproportionately heavy casualties). Fifteen years later, despite the lesson reinforced in Grant Hamilton's cartoon, America again wrestled with questions of inadequate military readiness.

Not every cartoonist was reverential about the Spanish-American War, or its hero Roosevelt. Horace Taylor drew this for the short-lived Verdict magazine, which was opposed to the war and anti-imperialist.