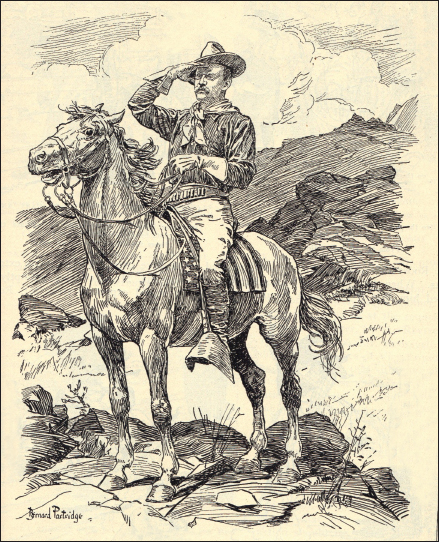

“NOW THAT DAMNED COWBOY IS PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES!”

Theodore Roosevelt and his family anticipated their first summer in Washington, D.C., as a sort of “calm before the calm.” The locals abandoned the swampy city each summer for cooler vacation spots, so the season promised to be a quiet one. And then TR looked forward to an autumn of inactivity, in the enforced lassitude of the vice president's office. The new vice president had resigned himself to spending four years (at least) in sedentary obscurity, despite the opinions of a growing number of friends that TR was destined to be president some day. The vice-presidency, they were sure, was merely another unorthodox path in a very unorthodox political career journey.

The Roosevelt family settled its affairs. Alice was a young woman now, and ready to enter Society. Alice later remembered being excited that her formal début would be as a White House lady, but she was “humiliated” that her parents served punch instead of champagne, and that the event was a dance without a cotillion. On the other hand, she also confessed to knowing no other girl “more frivolous and inane, more scattered and self-centered” than she at that time. Ted had been packed off to Groton prep school, with his sights set on Harvard. Roosevelt set about bundling the rest of the family from Oyster Bay to Washington again. He arranged a reasonable rental of the small mansion owned by Ohio friends, the Bellamy Storers, as there was no official residence for the vice president in those days. TR presided over the Senate for a couple weeks after the March 4 inauguration, before Congress adjourned until November. Then he took advantage of the long break to go hunting in Colorado.

After two extremely hectic years, he also looked forward to spending more time with his children, planning trips and activities. Even when his schedule was busiest, however, TR never failed to make time for romps and stories and hikes and chats with his children. He even famously declined invitations to the White House when they conflicted with his time with his “bunnies.” During this half-year, TR inaugurated the first of what was intended to be a series of informal meetings with college students (the first group comprised of students from Harvard and Yale) to discuss programs of commitment and service to civic reform. He also arranged to receive tutoring in the law from, of all people, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He officiated at the ceremonies opening the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. The list of his scheduled activities went on—to most people, a busy schedule, but for Roosevelt, a sedate interregnum. It was not destined to last.

Roosevelt's brief period of “rest” ended abruptly on September 6, 1901. President McKinley visited the Exposition in Buffalo himself and, while shaking hands with the public, was approached by a man whose hand was wrapped in a handkerchief, concealing a .32 caliber revolver. Leon Czolgosz, son of Polish immigrants and a disciple of anarchist Emma Goldman, shot the president twice in the abdomen, at point-blank range. Five weeks earlier, King Umberto I of Italy had been assassinated by an anarchist, an act that supposedly inspired Czolgosz. Seven weeks after murdering William McKinley, Czolgosz was arraigned, tried (he never entered a plea, nor cooperated with lawyers, nor spoke a word in self-defense), convicted, and executed. Similar swift justice had been meted out to President Garfield's assassin Charles Guiteau twenty years earlier, in an America very different from ours today.

TR rushed to the president's bedside in Buffalo, at the residence of the Milburn family, after the shooting. He left the city immediately upon making a brief visit. Doctors were optimistic about the president's recovery, and both Roosevelt and White House advisors considered it ghoulish to hover at the scene. Moreover, the public needed to be reassured of the president's prognosis. Convinced that all would be well, TR remained in New York, going off to hunt and hike in the Adirondacks. Shortly thereafter, a guide located the Roosevelt party in a remote and barely accessible portion of the mountains late one night and reported that the president had taken a turn for the worse. TR clambered down long, winding, muddy trails in the dark, and learned at a lodge where he stopped for further news that the president had died. He engaged a horse-drawn wagon and driver to take him the rest of the way down the mountain. In the moonless night, they descended seventeen miles of treacherous trails, TR frequently prodding the nervous driver to plunge the buckboard along the inky paths. “Push along! Hurry up! Go faster!”

It had been six months and two days since the inauguration of McKinley. Suddenly this young man Roosevelt (forty-two at the time, and the youngest man to date to serve as president), with young children still at home, was the leader of a country that had only recently reinvented itself by conquering a continent, winning a war, and gaining an empire. Theodore Roosevelt was president of the United States. America might have felt insecure about the upheaval and sudden change in government, except that the country knew TR. He had not come from nowhere. His splashy successes as governor of the largest state in the Union were well known; he was also a war hero and a familiar figure in the news, where he had been a highly visible reformer with two decades' worth of battle scars.

Moreover, America knew more about TR than his political and military résumé. He had written best-selling books in varied fields—history, civic affairs, and natural history. His exploits as a cowboy were famous, both from his own books and from the accounts of others. He wrote streams of articles for magazines, from popular monthlies and academic journals to children's magazines and Christian periodicals. When Theodore Roosevelt took the oath of office on September 14, 1901, in the parlor of the mansion of a Buffalo citizen named Wilcox, America needed no introduction to its new president, and few people were nervous about the future.

One man who was nervous, however, was William McKinley's best friend and political guide, Senator Mark Hanna—the man who as Chairman of the Republican National Committee had been adamantly opposed to Roosevelt's nomination to the vice-presidency, warning his fellow politicos: “Don't you realize there's only one life between that madman and the White House?” Now he cried to friends, “That damned cowboy is president of the United States!” What worried Mark Hanna was not the dust on Roosevelt's boots before entering the White House, but the dust he would raise once he was there. Despite TR's sincere declaration that he would “continue, absolutely unbroken, the policies” of the McKinley administration, very few Americans doubted that their nation would be turning a page…maybe several pages.

After scrambling down the mountain, the “cowboy” Roosevelt borrowed formal wear from the ceremony's host Mr. Wilcox, and he met McKinley's assembled cabinet—his cabinet now, for he asked every member to stay on—to take the oath of office. Among the notable figures present for the oath-taking were Secretary of War Elihu Root—who had been one of TR's mentors when he ran for the Assembly two decades earlier—and Secretary of State John Hay, a personal friend of TR who had also been close to the elder Roosevelt a generation earlier.

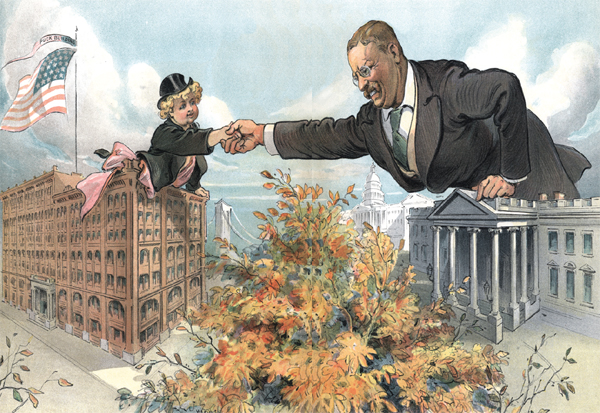

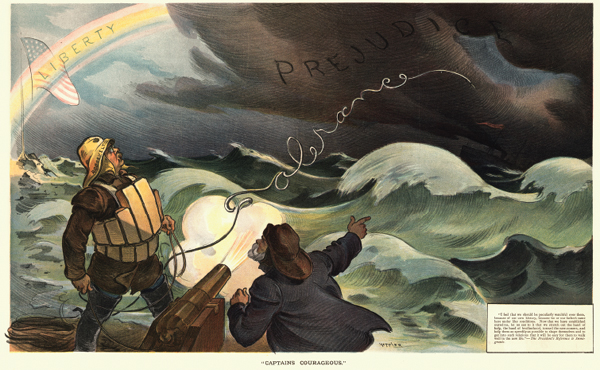

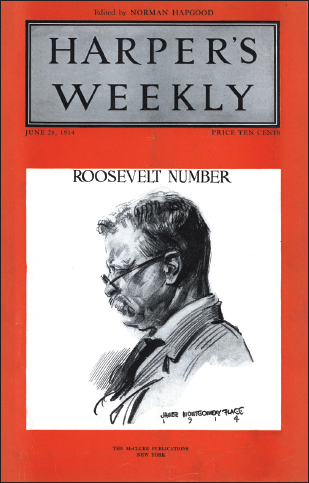

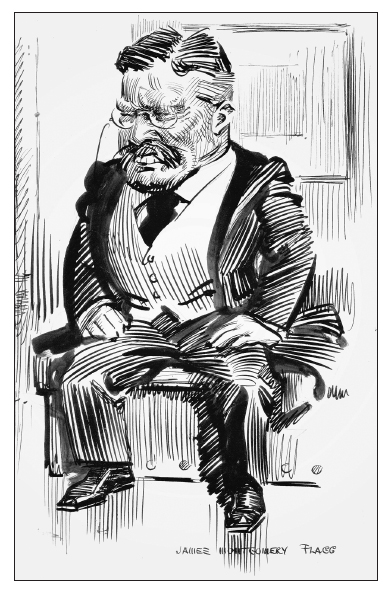

The great cartoonist and illustrator James Montgomery Flagg expressed the feelings of many Americans, especially after an anarchist murdered the president, as the new century argued peril or promise.

TR's dinner guests on his first day as president were only family. The Roosevelts were a tight-knit clan, conscious of their heritage and mindful of their exceptional gifts. Theodore gathered the immediate family that evening for encouragement as he prepared to embark on this new, exciting, and challenging period of his life.

Anna, the eldest sibling, nicknamed Bamie and Auntie Bye, was by numerous accounts the most remarkable of women, a brilliant conversationalist and intimate of the literary, diplomatic, and social elites of two continents. She had reared Alice for the first three years of her life, and received her again and again through the years, whenever a firmer hand than those provided by Theodore or Edith was required; Alice could be a handful. Alice, in her autobiography, stated that Auntie Bye could have risen to the American presidency herself, if the system had allowed—and if TR had not been on the scene. By the time of TR's elevation to the presidency, Bamie was Mrs. William Sheffield Cowles, wife of a sedentary admiral. One of her homes was in Washington, D.C., where she maintained a notable salon of the intellectual and power elites. She opened her home to the new First Family while Mrs. McKinley slowly vacated the White House. Through the years, Bamie, as much as Edith or Cabot Lodge, was one of Theodore's closest confidants and advisors.

The other Roosevelt sister, Corinne—Mrs. Douglas Robinson—was similar to Bamie in intelligence and wisdom. Her husband was in finance and advised Theodore in the realms of money that forever mystified him. Corinne became a poet of fair reputation. Both Corinne and Bamie were unwavering hero-worshipers of their brother, sublimating many prerogatives and personal goals on his behalf. This was, of course, in part because it was an age before women could assert themselves, but also largely in devotion to their exceptional brother.

One sibling was not there for the family dinner at the White House. Elliott (father of the future first lady Eleanor Roosevelt)—who had been a young man more dashing and daring, and certainly handsomer, than Theodore—had died almost a decade earlier. Elliot was a character not in keeping with the rest of his immediate family. Something of a playboy, he led the life of a sportsman and foreign hunter, growing increasingly dissolute. His drinking problems led to financial troubles. He was also sexually promiscuous, leading to a failed marriage. And he died in a cheap apartment in the arms of his mistress.

President Theodore Roosevelt's first dinner was appropriately private, a time for reflection, spiritual renewal, and inspiration. Family was always as close as TR's very heart, and as present as every horizon in his field of vision.

Even his beloved father was “present” at that dinner in a certain way. TR noticed, for instance, that by sheer coincidence the flowers set on the table were his father's favorite variety. The day was also his father's birthday. Indeed, he felt his father's influence and presence very strongly as he began this most strenuous period of his public career. He would write, “I have realized it as I signed various papers all day long…. I feel as if my father's hand were on my shoulder, and as if there were a special blessing over the life I am to lead here.” For all the distant and worthwhile goals that TR likely harbored, whether in the forefront of his mind or in inchoate ambition, he knew that he could travel farthest by staying close to his father's values and wisdom.

Neither introspection nor the multitude of new responsibilities averted TR from his form. As he noted, he signed many papers his first day. In his early days in the White House he also wrote many letters, received many visitors, and among his very first acts he invited the black educator Booker T. Washington to the White House, to discuss federal appointments and reform measures for blacks. White southerners (and many northerners) were outraged. The firestorm of opposition merely stiffened Roosevelt's resolution to let all citizens know that he was their president, regardless of their race. He also wanted to send a clear message that no one could dictate his course of action. As he took over the White House, while respecting McKinley's memory, TR did not refrain from sinking his teeth, and his spurs, into the presidency. He wrote Lodge that, although he had succeeded to the office by a dreadful circumstance, “It would be a far worse thing to be morbid about it.” The fact was that he was obliged to go to work as president. From the start, he was busy. He met with congressional leaders and the diplomatic corps, issued policy statements, and drafted his State of the Union message.

The first week proved to be a microcosm of Theodore Roosevelt's entire presidency. Based on those early days, no one should have been surprised by TR's initiatives or accomplishments during his tenure. His policies evolved, certainly, but in line with the changing times. His views on social unrest, economic hardship, corporate greed, union abuses, conservation, national interest, righteousness, the “manly virtues,” the sanctity of the family, military preparedness, and countless other issues, hardly changed at all over the course of his public life. TR's solutions and programs changed, of course, if only because the system's toleration of injustice sparked the public's intolerance of the status quo; and that shaped his view of the government's responsibilities. However, Roosevelt's basic views on the relationship between capital and labor, social and industrial justice, and the individual's role in society scarcely changed. The presidency merely gave Roosevelt an opportunity to focus his advocacies and to better achieve some of them.

The seeds of the issues he would make his own during his presidency had been planted during his days as New York Assemblyman, and later as governor of the state. His earlier efforts for better conditions in New York tenements, and his work to combat the evil collusion of big business, politics, and the courts, as well as his battles against railroad monopolies, coal mine owners, and meat packers, were the same issues he would strive for during his presidency, but now on a larger platform.

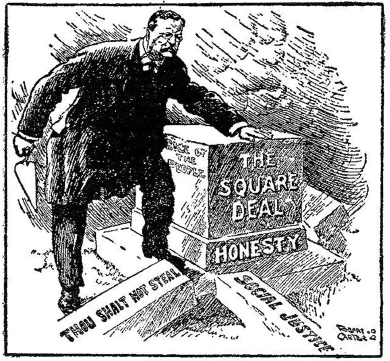

Roosevelt's abhorrence of political corruption likewise was a conviction he had developed early, certainly strengthened by his father's victimization in the brazen political mud-fight in New York back in 1877. “Without honesty,” TR once said, “popular government is a repulsive farce.” In his first week as president, he announced to a delegation of congressmen that if he could not find good Republicans to appoint, he had no problem with good Democrats. Soon thereafter he nominated an Alabamian Democrat to a federal judgeship.

His policies, then, had been on display for decades in countless speeches and articles. The only surprise as TR threw the society—or at least the government—into overdrive was that the American public offered little resistance. In fact, it seemed happy to be along for the ride. Times were ripe for change: that is undeniable. Yet much of the transformation of the culture's attitudes was due to the fact that TR preached reform, not revolution. And, as always, he was clear that reform was the antidote, not a mere substitute for (or postponement of) revolution. By these attitudes, Theodore Roosevelt proved himself to be at core a conservative. He claimed Lincoln as his model and described himself using terms like “sane radical” and “progressive conservative”—in a time before the words were made oxymoronic. To his bemusement, socialists, or at any rate social reformers, were often attracted to his policies. He ultimately would dismiss many of these followers as the “lunatic fringe.”

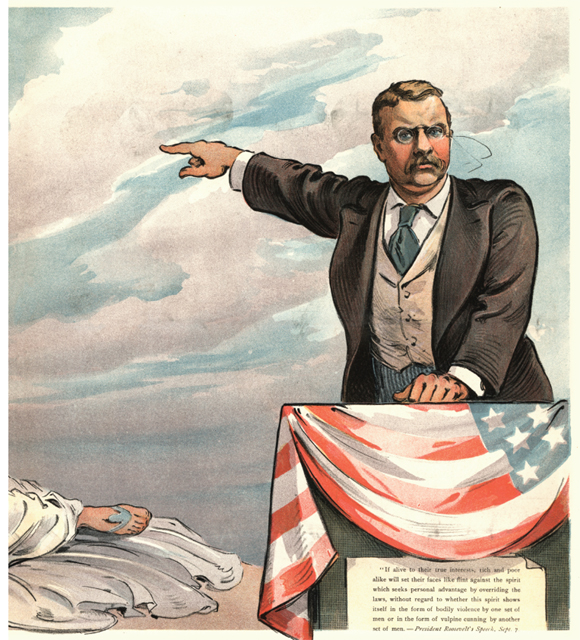

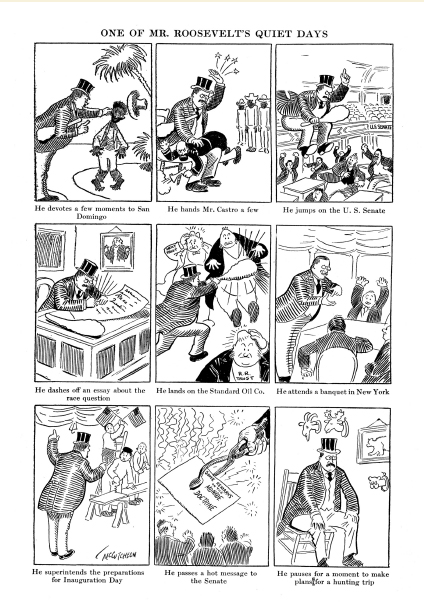

There is another, easily missed reason why the public so quickly—and enthusiastically—embraced his policies: Theodore Roosevelt explained his positions well. He had a gift for persuasion and a talent for finding the perfect phrase to encapsulate a concept. Besides, his personality was magnetic, and people wanted to hear what he said and like what he liked. He was wise enough to accede to the hunger of cartoonists and reporters, and he knew the value of going over the heads of legislative opponents, straight to the people. The presidency afforded TR a virtual pulpit; “a bully pulpit,” he frankly called it, in the jargon of street kids of the day (“bully” being more common in the mouths of cartoon gamins in magazines and newspapers than in presidential speech). The term has survived, but few presidents have exercised it so well, or used it so often, as did Theodore Roosevelt.

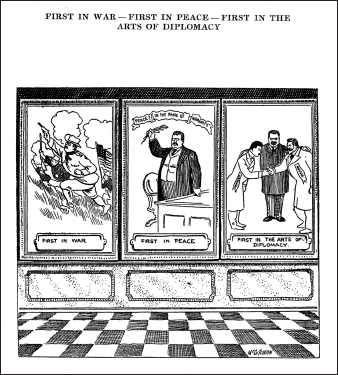

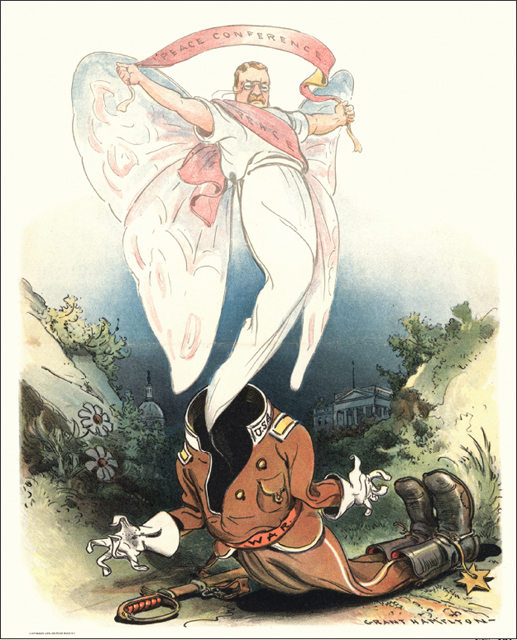

TR, in the minds of his detractors a warmonger, established a substantial record of effective work on behalf of hemispheric and world peace, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for his actions.

One charge often leveled against Roosevelt is that he expanded presidential powers during his time in office, often acting contrary to tradition, for peace, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for his actions. He routinely bypassed secretaries to consult with lower-echelon experts. As a result, his opponents frequently charged that he ignored time-honored practices, and even the Constitution itself. Roosevelt believed the president should be free to act in any manner that is not specifically prohibited. He once said that when he felt “certainly justified in morals,” he was “therefore justified in law.” If nothing else, this suggested that TR was as naive in legal matters as he was in economics.

Another example of his view on the subject of presidential powers derives from a compliment he once paid to Senator Spooner, who desired to sit in the Cabinet instead of the Senate. Roosevelt told him, “What I need is a great Constitutional lawyer right at my side every minute.”

Spooner replied that two of the country's best constitutional lawyers, Root and Taft, already served in the cabinet.

“I know it,” TR admitted; “but they don't agree with me.”

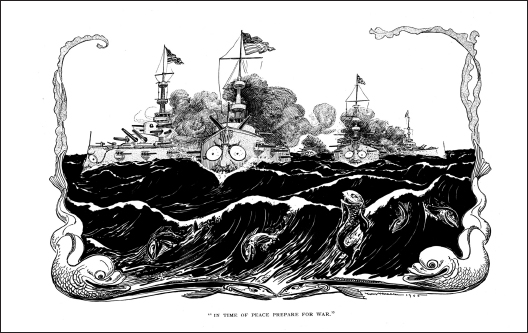

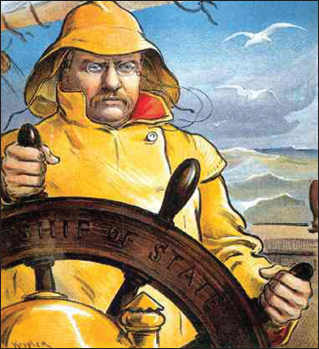

A similar case concerns the Great White Fleet. As a contribution to worldwide peace, Roosevelt wanted to assemble the American fleet, paint it goodwill-white, and send it on a world tour of great nations. The purpose would be to assert America's presence as a great power and affirm her value as an ally. The mission would also serve as a warning to any potential adversary. A recalcitrant Congress refused to appropriate funds for the cruise. TR ordered the Great White Fleet to sail anyway, requiring Congress—if it wanted the Navy back in American waters—to appropriate funds needed for the project's budget.

Roosevelt recognized that sometimes the only way to get things done was to do them.

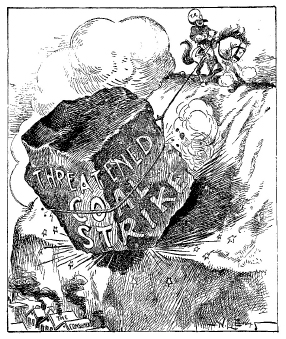

THE COAL STRIKE

Early in his presidency, TR averted a potential national disaster. Coal miners in the anthracite fields of eastern Pennsylvania called a strike over grievances related to pay and safety of the workers. The maximum pay for miners at the time was $10 a week, and nearly 500 miners had died in safety-related accidents the previous year. Workers were bound to live in company towns, and there were no such things as workman's compensation provisions. The mine owners flatly refused to negotiate with the newly formed United Mine Workers, which called the strike in May 1902. By chilly autumn, the public was restive about prospects of no coal, or high-priced coal, during the upcoming winter. Already, schools were closing on particularly cold days.

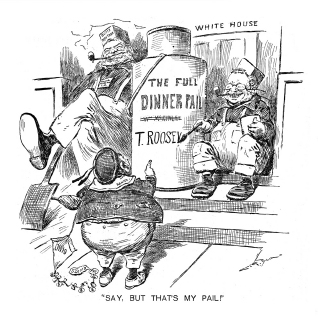

TR directly intervened, the first time in U.S. history that a president attempted to arbitrate a labor dispute. The union chief, John Mitchell, offered to abide by the findings of an arbitration panel proposed by Roosevelt. The mine owners' representative, George F. Baer of the Philadelphia and Reading railway, refused to participate, and even lectured the president peremptorily. TR, who later confided that he could barely keep himself from bodily throwing Baer from the room, announced he would consider sending 10,000 U.S. soldiers to operate the mines in the name of a public emergency, to keep people from freezing over the winter. Cabinet member Elihu Root, a former Wall Street lawyer, met with J. P. Morgan in New York, asking him to persuade the mine owners to change their position.

Coal barons agreed to arbitration, but even then there were evident scales over the eyes of some businessmen. The arbitration panel was to be composed categorically by the backgrounds and credentials of its members. The size of the panel proved a sticking point, as did the owners' unwillingness to accept anyone suggested by the miners. They even vetoed in advance former president Grover Cleveland, whom Roosevelt had asked about serving. Roosevelt wanted to offset the owners' representatives with one who would advocate the laborers' point of view, creating a balanced panel. He proposed the Catholic Bishop John Spalding, who knew miners and their conditions, but the mine owners balked. Roosevelt realized that the only unfilled position on the panel was for an “eminent sociologist.” He thereupon named Bishop Spalding, but called him an eminent sociologist. Surprisingly, the mine owners offered no objections.

“It dawned on me that they were not objecting to the thing, but to the name. I found that they did not mind my appointing any man, whether he was a labor man or not, so long as he was not appointed as a labor man, or as a representative of labor,” Roosevelt later wrote. “I shall never forget the mixture of relief and amusement I felt when I thoroughly grasped the fact that while they would heroically submit to anarchy rather than have Tweedledum, yet if I would call it Tweedledee they would accept it with rapture: it gave me an illuminating glimpse into one corner of the mighty brains of these ‘captains of industry.'”

Miners went back to work on October 16 when the commission was officially comprised. The public—a public exceedingly grateful to President Roosevelt—was spared a huge crisis.

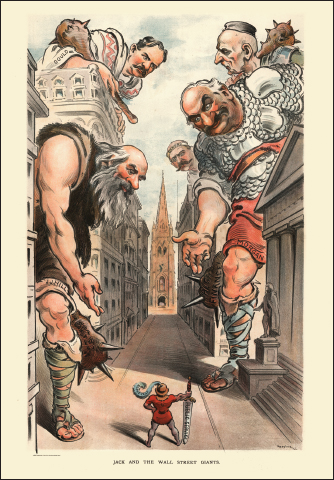

TRUST BUSTING

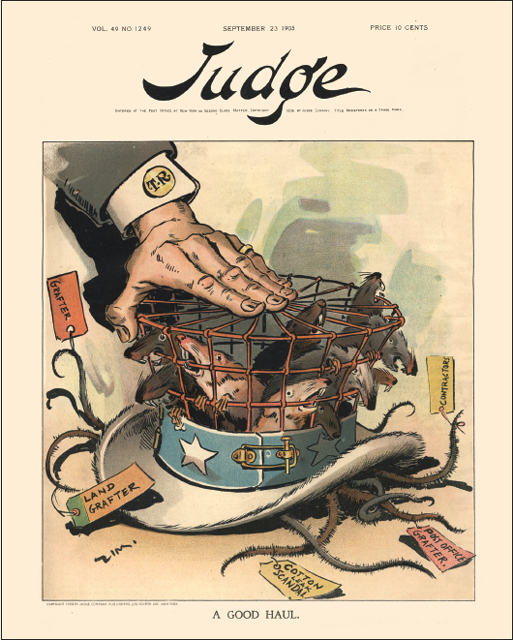

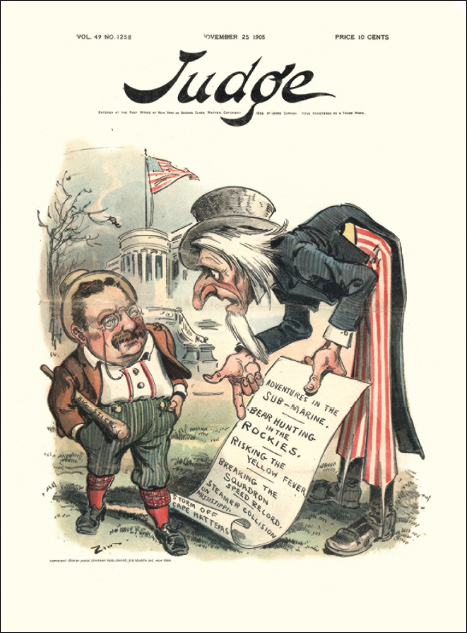

More than any other topic, Roosevelt's “attitude toward the relations between capital and labor” worried Republican leaders and Wall Street. No matter that the Sherman Anti-Trust Act was passed under a Republican president by a Republican congress, written by a Republican icon (Ohio Senator John Sherman, later Secretary of State under McKinley, and a brother of the Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman), who possessed about as orthodox a pedigree as conservative industrialists could wish. A consensus prevailed in the country that the evils of monopolies far outweighed any benefits they might bestow, and that, unchecked, abuses would multiply. Even conservative Republican journals, like the GOP-subsidized Judge, railed against trusts. Trusts and high tariffs were center-stage of every presidential campaign since the 1880s. President Cleveland even devoted his State of the Union message in 1888 exclusively to the “immoral” government budget surplus caused by policies related to trusts and high tariffs. Before or since, that was the only Annual Message ever devoted to one topic.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, most politicians at least paid lip-service to opposing interstate combinations such as the Sugar Trust, the Wheat Trust, the Steel Trust, and so forth. Even McKinley had said that the challenge of unchecked industrial combinations needed to be studied. William Jennings Bryan, more than most politicians, really seemed to believe his own radical proposals to break up and outlaw trusts. Wall Street, and its disciples in the Senate such as Mark Hanna, breathed a sigh of relief when TR devoted only a few lines of his first Annual Message to the issue.

Then, in February 1902, TR dropped a bombshell that startled even most cabinet members. The president instructed Attorney General Philander C. Knox to file suit against the newly formed Northern Securities Company. The $400 million holding company merged the railroads of titans Edward H. Harriman and James J. Hill, which would have resulted in a monopoly in the northwest quadrant of the United States. The architect of the merger was financier J. P. Morgan, in whose New York social set the Roosevelts were members. Morgan treated the issue as something that friends could settle over dinner. “If we have done anything wrong, send your man to my man and they can fix it up,” Morgan wrote TR. He also asked whether the suit threatened any other interests or trusts. Roosevelt's reply could not have been very reassuring to robber barons: “Not unless we find out…they have done something we regard as wrong.”

The landmark anti-trust suit was successful. It was appealed, and the Supreme Court upheld the dissolution of Northern Securities in 1904. The Sherman Anti-Trust Act had finally grown teeth, and TR received one of his many nicknames—“The Trust-Buster.”

Roosevelt did not believe he was pulling down the pillars of American capitalism in his crusade against trusts, but rather saving it from its excesses and corruption. TR believed that trusts were not to be opposed on account of their size. It was not bigness, but wrongdoing, that merited attention. He believed when small competitors were unfairly crushed, or when prices and rates were manipulated so as to cause consumer distress or violate standards of supply and demand in such cases it was incumbent upon the government to play referee. For instance, railroads often issued rebates to favored customers and hid those practices from the public, creating instability, inflating retail prices, and polluting the supply-and-demand mechanisms. As trusts were established across state lines, TR was convinced the national government should be responsible. In this as in many areas, Roosevelt adopted a national policy inherited from Hamilton, Clay, and Lincoln. This was not the Jeffersonian denial of evolutionary growth, which attitude viewed all trusts as evil (and which Roosevelt termed “rural Toryism”). Courts and legislative bodies were supposed to pursue justice and defend vulnerable entrepreneurs and consumers, but for decades judges and lawmakers had proven themselves willing tools of the trusts. The system had been rigged for far too long.

“I AM NO LONGER A POLITICAL ACCIDENT”

TR's old nemesis Mark Hanna was still a senator from Ohio and still chairman of the Republican National Committee during Roosevelt's first term. When the time came for Roosevelt's renomination, the meager opposition within the party coalesced around Hanna; a willing spokesman for Big Business, he attracted the “stand pat” element resistant to reform. But any potential run for the presidency by “Dollar Mark” was derailed by a perfect storm of political machinations by Ohio's junior senator Joseph B. Foraker who, though not particularly fond of TR, was a rival of Hanna. A full year before the convention, Senator Foraker engineered a motion that the Ohio party establishment endorse the policies and renomination of Roosevelt. Hanna tried to avoid the box by cabling TR that he would abstain from the resolution for reasons Roosevelt would approve “when you know all the facts.” Roosevelt knew all the facts he needed. He publicly responded, “I have not asked any man for his support…inasmuch as it has been raised, of course those who favor my administration and my nomination will favor endorsing both, and those who do not will oppose.” Match, set, and game.

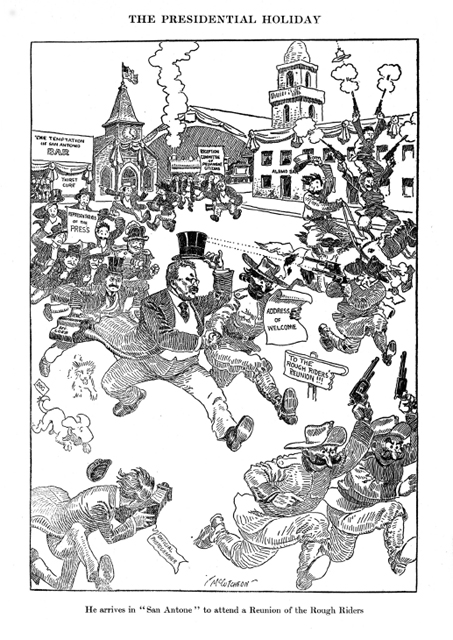

Roosevelt set out on speaking tours to all parts of America. In Pittsfield, Massachusetts, on September 3, 1902, he narrowly escaped death and was seriously injured when an electric street car collided with the presidential carriage; this resulted in TR's confinement to a wheelchair for several weeks.

Despite his accident, Roosevelt never curtailed his travel and speaking schedule. He probably “hit the trail” more than any previous president. He enjoyed massive support from the public, not just for his policies but for his person.

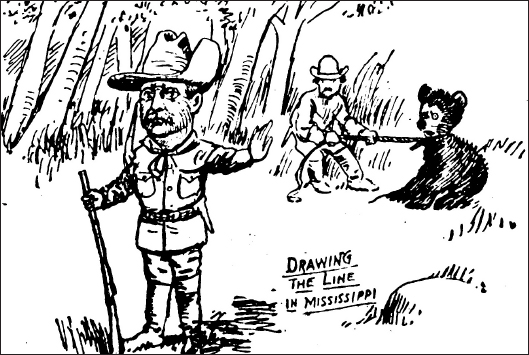

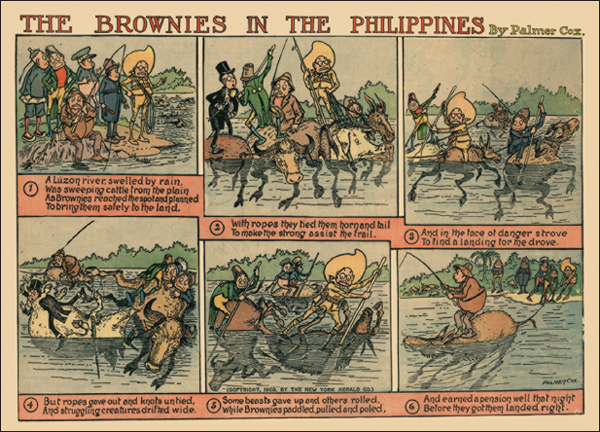

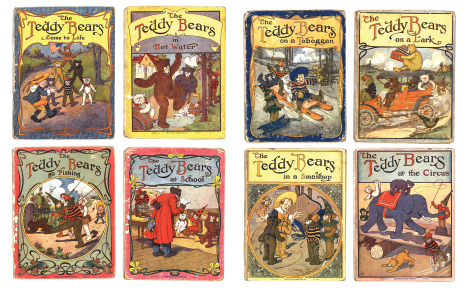

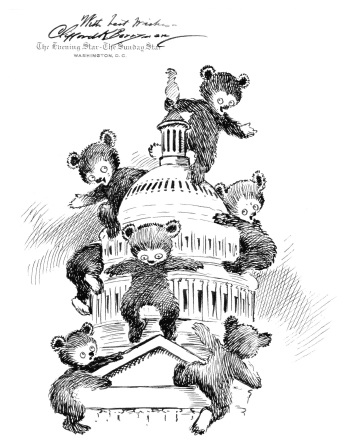

Late in 1902, TR went bear hunting in Mississippi. After three days, and no bears spotted, a guide and his hunting dogs finally found an old bear. The dogs injured the bear, and guides tied it to a tree and called for the president. TR refused to shoot the bear, except to put the old fellow down, so old and infirm was the animal. The political cartoonist of the Washington Post, Clifford K. Berryman, memorialized the incident in cartoons. The first cartoon was a vignette in a larger group of cartoons of the week's events, and depicted TR refusing to shoot an old bear. A second, cleaner cartoon, drawn in response to public interest, showed the bear as a cowering cub. This cute bear cub began to appear in other Berryman cartoons. Eventually, this bear cub became Berryman's dingbat (a cartoonist's mascot). Roosevelt called it the Berryman Bear; Berryman called it the Roosevelt Bear; but everyone else called it the Teddy Bear. After this famous cartoon appeared in the papers, a Brooklyn shopkeeper, Morris Michtom, took two stuffed toy bears his wife made and put them in his shop window. He called them Teddy Bears and found instant success. His store eventually became the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company. Other companies such as Germany's Steiff soon followed suit, and an eternal identification was born.

All across the continent, TR wanted to see the people, and the people wanted to see him. The Democrats briefly put William Jennings Bryan on the shelf and nominated the conservative New York judge Alton B. Parker. Because Roosevelt had attracted many proponents of reform and change to himself, the Democrats had nowhere else to turn but to old-line platform planks. In the 1904 election, TR won a smashing victory, even breaking the “Solid South” and carrying Missouri. Of all people, Roosevelt himself was most surprised. He said to Edith: “I am no longer a political accident.”

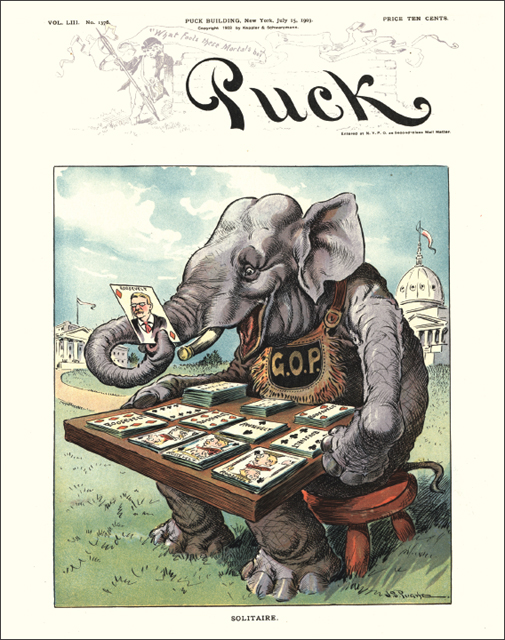

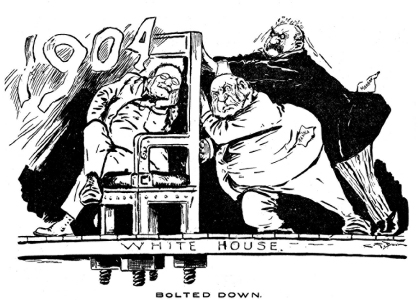

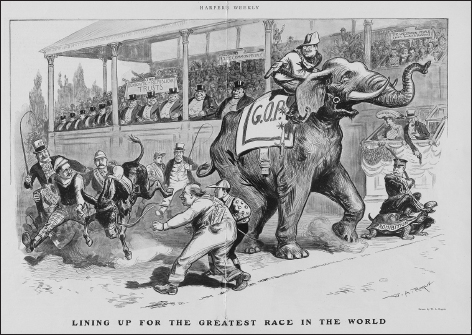

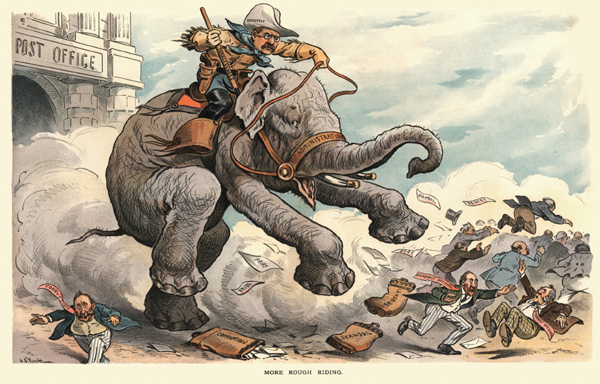

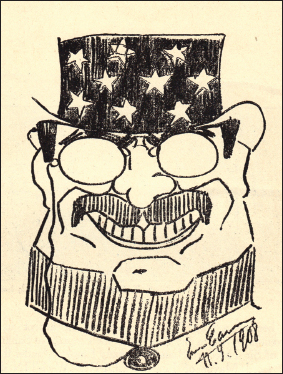

As the 1904 election approached, for the Republicans “everything was coming up Rooses.” A cartoon by J. S. Pughe in Puck.

On election night he made a public statement, however, that made Edith and friends like Cabot Lodge blanch. “Under no circumstances will I be a candidate for or accept another nomination.” Whether his motivation was humility in gratitude, or simply signaling a desire to do other things with his life four years hence, it cemented his status as an instant lame duck, emboldening congressional reactionaries to oppose him. And the statement would seriously complicate matters later, when he sought a non-consecutive term in 1912.

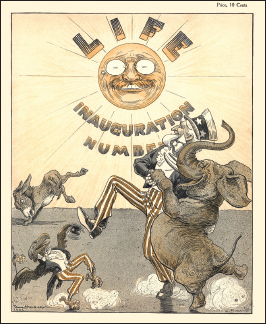

President Roosevelt's inauguration was a predictable, glorious, red-white-and-blue circus. Secretary of State Hay presented the son of his old friend—now his chief—a ring with a locket containing Abraham Lincoln's hair (Hay had been Lincoln's secretary). TR was touched, and he wore the ring when he took the oath of office. In the inaugural parade, coal miners, cowboy friends, and (of course) many Rough Riders romped down Pennsylvania Avenue.

“How I wish father could have lived to see it too,” TR wrote to an uncle.

“SPEAK SOFTLY AND CARRY A BIG STICK”

Throughout his two presidential terms, TR maintained staunch, clear policies. Just as in domestic affairs no one doubted where he stood on any issue, so too in foreign policy he left no room for confusion. Besides his trademark no-nonsense approach (encapsulated in his use of the old West African proverb: “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far”), Roosevelt had a real knack for diplomacy. Cartoonists seized upon TR's foreign policy aphorism of the big stick, and it quickly became an icon. In the end, though, the remarkable successes of Roosevelt's foreign policies had less to do with the decibel-levels of his speeches and the heft of his bludgeon, than with his pitch-perfect instincts and sagacity. He knew how and when to act. “Nine-tenths of wisdom,” he once said, “is being wise at the right time.”

In 1904, an American citizen, Ion Perdicaris, was kidnapped in Morocco. The Berber tribal chief Raisuli schemed to embarrass the nation's Sultan by demanding $70,000 in ransom, partly to reveal the national government as powerless. TR cared not a bit about the internal dynamics of North African tribal disputes. When John Hay forwarded the president's reaction in a cable—“Perdicaris alive, or Raisuli dead”—Americans were electrified. The American likely was released before the actual cable reached Morocco, but the results were the same; the world knew where the U.S. president stood while TR was in office—that much was abundantly clear. Bluffs and equivocations were not in his vocabulary.

Morocco, coincidentally, was the site of another foreign-policy triumph for Roosevelt as a proactive peacemaker, a year later. Many details of his diplomacy in this situation, which defused a flash-point between colonial powers and perhaps diverted a European war by a decade, were not publicized until fifty years later. Germany, an emerging world power, had few areas of the world in which to expand its commercial activities. Other countries entered into secret agreements to constrict Germany on the continent and on sea—most notably England, France, and Russia, who would secretly work to support each other's actions. The German Kaiser appealed to President Roosevelt to mediate a solution to a crisis in Morocco, a potential battlefield. Germany had been frozen out of political influence in the North African nation but at least wanted an international guarantee of an “open door,” as had recently been established vis à vis China.

TR undertook the role of mediator, with no certain prospect of success. American troops, he insisted, would not become engaged. This was peacemaking. At the Algeciras (Spain) Conference he was represented by his trusted chief diplomat Henry White. All parties were pleased, or at least satisfied, as Germany gained minor concessions but major prestige. And the very real threat of war was averted.

Another largely thankless diplomatic challenge was undertaken by President Roosevelt in 1905. The world had grown concerned about a conflict between Russia and Japan. Begun over commercial prerogatives in Manchuria and northern China, disagreements had extended into seaport rights and territorial claims in the Pacific, and a host of other issues. War was declared after a surprise attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur. For months the European powers looked on with dread for the future, disqualified as effective mediators because of entangling military relationships. No country besides the United States appeared to be an honest broker. When the combatants had finally bled themselves dry and acceded to mediation, TR assumed the responsibility to bring about an end to hostilities.

Roosevelt quickly realized that a large component of statecraft is personal persuasion. The Japanese and Russian representatives were suspicious, jealous, and vain, often more concerned with protocol than peace. TR countered these idiocies by clever means. Who would enter the conference room with the president, in which order? TR managed to engage everyone in lively conversation, passing through the doorway together, before any of the plenipotentiaries realized exactly how they had arrived. Who would sit where, in relation to the president and each other? TR anticipated that nonsensical concern by having the wardroom chairs on the presidential yacht, where the parties first convened, unbolted from the floor. Chairs were instead arranged in a more informal, collegial pattern.

Such inanities, catering to whims and sensibilities, are often as important as matters of territories or indemnities in the world of negotiations, and TR proved to be a perspicacious master of diplomacy. He proposed scenarios, and very secretly consulted with (and solicited pressure from) England and, especially, Germany at certain points. He insinuated himself in the discussions only as much as he thought most useful. When things had gotten further along, he moved the site of the negotiations to Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

It was exhausting work, and TR grew exasperated with both delegations—but especially the Russians, whose obsession with minor concerns and meaningless points confirmed the impression that the Czarist regime was adrift. At one point he released steam in a very unorthodox way. An experimental submarine, the Plunger, was ready for testing. TR descended for an hour into the waters of Long Island Sound, off Oyster Bay, to examine the submarine's technology, experience a thrill, and clear his head. He was rather roundly criticized for recklessness when the news was later made public, but this one of many “firsts” did clear TR's head. Soon afterward he secured a peace treaty between Russia and Japan. In summary, three weeks of intense negotiations resulted in Japan retaining Port Arthur and gaining a protectorate over Korea. Russia avoided indemnities and agreed to share the island of Sakhalin with Japan.

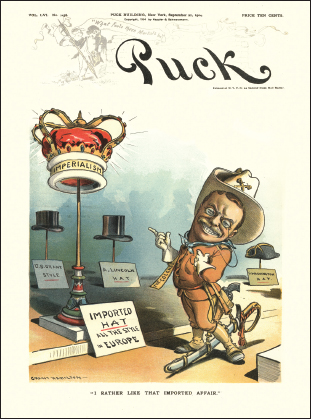

In the end, TR became the first American president to win the Nobel Peace Prize, among many other “firsts” in his presidency. It was an ironic honor for the war hero frequently caricatured by cartoonists in Rough Rider garb, guns in his holsters or his hands, challenging some foreign foe, or anyone in the neighborhood. But it was fitting, too, for the man whose credo was, “If I must choose between peace and righteousness, I choose righteousness,” but believed that without righteousness peace was fleeting.

“I TOOK THE ISTHMUS”

In many ways, the foreign-policy landmarks of the Roosevelt administration can be told through the same subtext as his domestic agenda: he averted crises due to his management and foresight. Much of the Old World, for instance, assumed that America would retain Cuba as a possession, yet straightforward initiatives to assist the island nation toward independence proceeded. Roosevelt believed that immediate independence would have disastrous consequences for the island, so he instated governors-general to oversee the establishment of civic structures. Yellow fever was attacked and virtually eliminated, under the direction of Dr. Walter Reed. TR, who had seen the effects of yellow fever firsthand, gave priority to this situation.

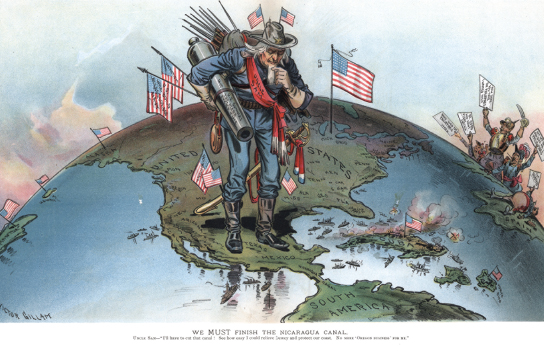

In the Caribbean basin, in Central and South America, there were local revolutions. This was nothing new, but European powers were being drawn into them, and this had previously unfamiliar aspects. Regional flash-points tempted Old World powers to test the mettle of the United States as an emerging world power. Also, Latin countries were growing ever more irresponsible in international trade, as many defaulted on debts and violated trade and customs rules with European powers, chiefly England and Germany. To promote statecraft in the hemisphere, and to keep European nations from fishing in troubled waters, TR established what came to be known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. This stated basically that America would intervene to schedule debt payments of rogue nations to outside powers, and would perform other such acts to promote regional order and national responsibility. Many people opposed Uncle Sam acting as a hemispheric policeman, especially dictators and military strongmen whose schemes were thus thwarted.

These interventions were uniformly bloodless, and accompanied by no-nonsense diplomacy explained with no ambiguities.

In the case of the Panama Canal, Theodore Roosevelt did not restrict himself to speaking softly; he spoke as required, acted as he saw the need, and took responsibility as he should. A canal through Panama, joining the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, saving weeks and vast distances on the seas (some of them dangerous), had been dreamed of for centuries. The construction of a canal through the relatively narrow strip of land connecting North and South America had actually been attempted in the 1870s and abandoned by the French, after expenditure of a quarter-billion dollars and widespread death from yellow fever and malaria.

In the United States, the concept of an isthmian canal was not new. Before Roosevelt took office, the United States had negotiated with both Nicaragua and Colombia, and Congress had appropriated funds for possible leases of land. Roosevelt needed no convincing. He realized the canal would be beneficial to commercial shipping, private sea travel, and the military. But he also felt that building an isthmian canal was an historical imperative. TR wrote that “building of the canal through Panama will rank in kind…with the Louisiana Purchase and the Annexation of Texas.”

The region in which the canal was to be built was in a constant state of unrest. The countries were small, with often-shifting borders; they dealt with deadly rivalries, ethnic and tribal competition, corruption, uncountable government overthrows, revolutions, and counter-revolutions. Colombia (and Nicaragua before it, in similar fashion) frustrated U.S. diplomats, who felt that the Central Americans seldom negotiated in good faith, or continually solicited bribes. A faction within a province of Colombia rebelled once again, and declared independence as the Republic of Panama. The United States recognized the new republic, and immediately concluded a treaty to lease land and build a canal through the middle of the new country.

It is not clear whether TR was aware of back-channel machinations between Panamanians, French representatives of the previous leaseholders, and nation-building brokers working, in effect, on commission; or that many of the diplomatic details of Panama's independence occurred in a New York hotel room, not in the jungles of Central America. In any event these would have been nothing more than details to TR. And a Navy ship sent near Colombian waters, ostensibly to protect Americans in the Panamanian province, probably influenced events. What was important was that a new nation had achieved its independence, and America—indeed, the world—was to have a significantly important canal.

TR viewed the Panama Canal as the most important achievement of his administration. To naysayers of his actions and rationale, he was unapologetic: “I took the Isthmus, started the Canal, and then let Congress, not to debate the Canal, but to debate me.”

An unprecedented achievement then took place: in less than a decade, the Americans cleared land and jungles and dug across a 50-mile wide swath of resistant land; they moved mechanical devices of mammoth proportions and set them in place; and they developed many important innovations in the process (as would happen in America's later space program). Cuba redux: deadly diseases traditionally considered incurable were attacked and conquered. Today the Canal Zone is virtually free from yellow fever and malaria. Roosevelt worked through a few false starts and consultations, enacting solutions that would ensure the construction's success. For instance, he decided on a system of locks instead of a sea-level approach, and he appointed directors with authority and competence, men like Colonel George W. Goethels of the Army Corps of Engineers, and doctors Walter Reed and William Gorgas.

The workers used massive bulldozers and cranes, dynamite and portable double-track railroad lines. They established workers' colonies with mosquito-netted buildings, social events, and even a newspaper. Construction proceeded, foot by grueling foot. Rusting equipment from previous failed endeavors littered the landscape where they worked, but the Panama Canal opened two years ahead of schedule. Ironically—or significantly (since military contingencies were important concerns to Roosevelt)—it commenced operations in August 1914, the same month that World War I began.

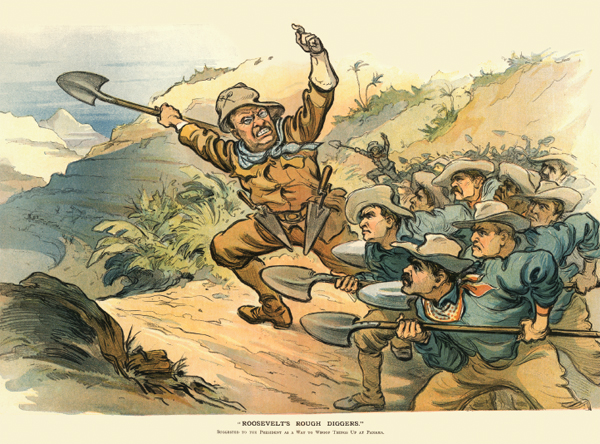

In 1906, Theodore Roosevelt became the first president ever to leave U.S. soil while in office. He sailed to Panama to inspect progress on his pet project. Of course, he was not content merely to observe the progress; ever the exuberant boy, TR was caught by photographers in the operator's seat of a gargantuan steam shovel.

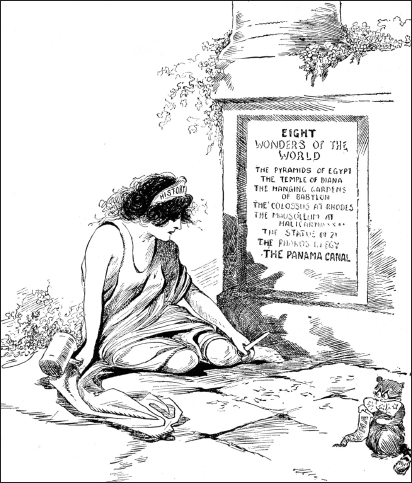

Almost a million vessels have passed through the Panama Canal since it opened. In every respect it is one of the wonders of the world's mechanical age. As TR predicted, his decision to move forward in building the canal was debated while the project itself proceeded, but he held firm. This astounding personal achievement of Theodore Roosevelt's has never been sufficiently recognized. It is unlikely that many other presidents could have managed the events and overseen such a bold project. Under his oversight, the jungles of Panama were transformed, a mechanical marvel was realized, ahead of schedule, without corruption or scandal. At the same time, the Americans conquered diseases in the region, benefited maritime trade, and confirmed the primacy of the United States.

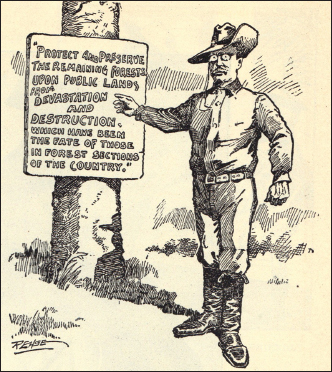

CONSERVATION

Among TR's domestic policies, perhaps the one for which he is best remembered is his initiative to conserve natural resources. His work on behalf of the nation's fields, forests, and habitats was sweeping. He regarded as some of his most significant domestic accomplishments the protection of vast tracts of land and the creation of parks, monuments, game preserves, and bird sanctuaries. Of TR's myriad interests, the love of nature and the care of the environment were among his earliest and most passionate. Protecting America's natural treasures was no easy task, for Congress was populated by many men who owed their political lives to lumber, coal, and mineral trusts. Also, many citizens believed that the country's resources were endless, and that exploitation required no reclamation. People did not recognize, nor did they care, that actions like deforestation and wanton animal slaughter would have serious national consequences. Roosevelt needed to educate just as much as he needed to initiate reform.

“In utilizing and conserving the natural resources of the Nation, the one characteristic more essential than any other is foresight,” TR said. “The conservation of our natural resources and their proper use constitute the fundamental problem which underlies almost every other problem of our national life.”

Many contemporary Americans cannot reconcile TR's love of hunting with his love of the natural world and his reverence for nature. Roosevelt's own accounts of camping, exploring, riding, hunting, of discoveries in the open spaces, and of contending and communing with nature should be sufficient to prove him a genuine naturalist. As a child he loved animals and birds. As an adult, he was a close associate and friend of many noted naturalists. TR was a world-class authority in many areas of natural history, contributing to the standard literature theories about mammalian affinities on different continents, and the protective coloration of fauna.

To understand Roosevelt's devotion to these issues, from a national and not a personal point of view, one must pay attention to his precise choice of words: “Conservation of Natural Resources.” He enjoyed the outdoors, but his policies were not motivated by pleasure. While he valued the heritage of open ranges, he understood the importance of advances in civilization, with its farms and fences. And he was mindful of the responsibilities of God's children to nurture God's creation. On the other hand, he advocated the development of woodlands, coal fields, and waterways; a growing nation required these things. He always coupled any exploitation with management: conservation, regrowth, and reclamation. More than replanting trees, he foresaw a national policy that would divert or dam rivers, reclaim land, and irrigate deserts. (The Roosevelt Dam on the Salt River in Arizona, begun in 1905 and the first of America's grand hydroelectric dams, honors his foresight.)

TR firmly believed these factors of conservation and development were not mutually exclusive. We honor nature by enjoying it to the full, learning and nurturing along the way, and we should leave the environment somehow better off than when we first encountered it. Many of the most beautiful natural preserves in our nation today might not exist but for the actions of Theodore Roosevelt.

TR's environmental legacy includes academic papers and books, and extraordinary numbers of museum exhibits and dioramas. But his impact can be seen especially in the outdoors. Over the course of his presidency, Roosevelt was responsible for placing approximately 84,000 acres a day under public protection, for a total of 230 million acres. Among these protected areas are 150 national forests, fifty-one federal bird reservations, four national game preserves, five national parks, eighteen national monuments, and twenty-four reclamation projects. In his last year in office, he convened a national conference to confront environmental issues. Governors of every state and territory were invited, as were cabinet secretaries, Supreme Court justices, scientists, and even William Jennings Bryan as leader of the loyal opposition. Among the results were position papers, and the creation of conservation commissions in thirty-eight states. (The annual National Governors Conference grew from this event.) Roosevelt's chief lieutenants in his conservation work were Interior Secretary James R. Garfield and Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot.

A few months after the first Governors Conference, TR appointed a Rural Life Commission to study environmental, economic, and quality-of-life issues. The Old Guard Senate, then in open revolt against any of TR's reforms, refused to print the commission's findings. The Spokane, Washington, Chamber of Commerce did so as a public service.

The conservation of natural resources was not completely original to Theodore Roosevelt; Presidents Cleveland and McKinley, for example, had set aside public lands for protection, and even some lumber companies were realizing that reforestation was long overdue on the American landscape. Roosevelt took the concept to vast new heights, and through his passion for the land, made a priceless and lasting bequest to the nation, preserving its heritage.

THE AGE OF THE MUCKRAKERS

The last two years of Roosevelt's presidency might, after all, have been everything the old Establishment types feared when “that damned cowboy” made it to the White House. It was a period of increasingly radical reform measures and urgent proposals from the White House. A spate of legislation kept pace with regulatory proposals. In the mid-term elections of 1906, a brash new group of congressmen and senators arrived in Washington. Contrary to all patterns, the president's party did not lose, but substantially gained, seats. And, significantly, most of those who swept in were ardent supporters of Roosevelt's policies. If anything, the new Congress prodded the president more than ever to agendas of reform.

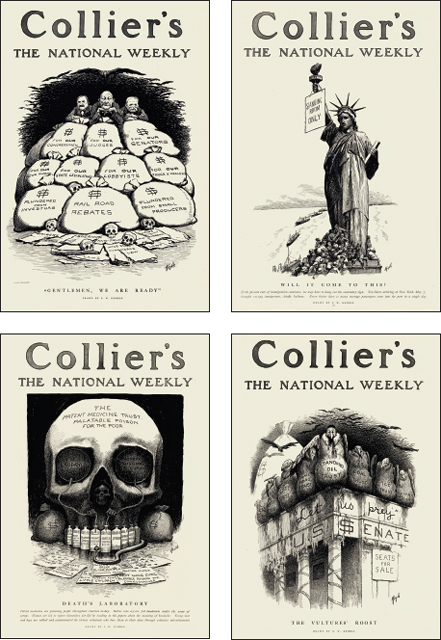

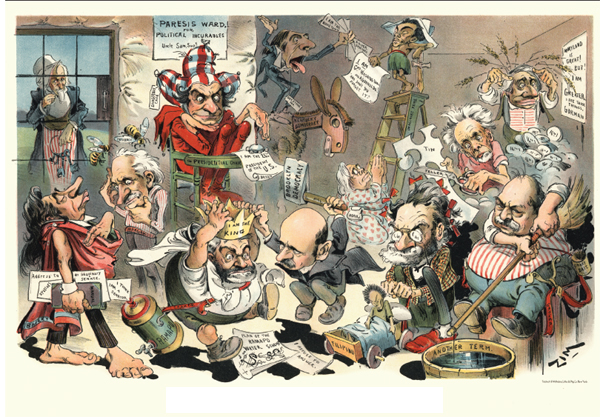

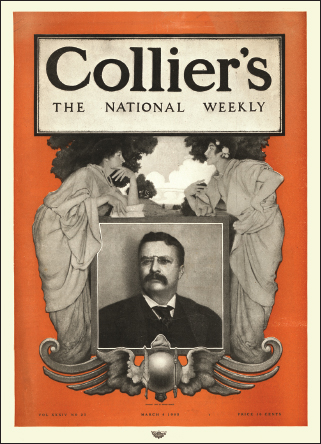

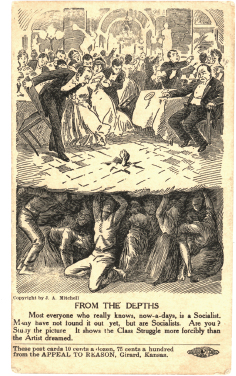

Collier's Weekly transformed itself from a family magazine like The Saturday Evening Post to a leading Muckraking journal during the Roosevelt years. Its covers, by E. W. Kemble, were as strong as anything Thomas Nast did in his heyday with Harper's Weekly.

Moreover, there was a new spirit in the land. Reform was the order of the day. Where before only a few periodicals touted reform measures (some of them, like Hearst and Pulitzer's newspapers, tinged with circulation-gathering sensationalism), now a legion of magazines regularly published exposés, revelations of corruption, shocking reports of lawbreaking in high places, exploitation of workers, scandals like squalid child-labor operations, and code violations in major industries.

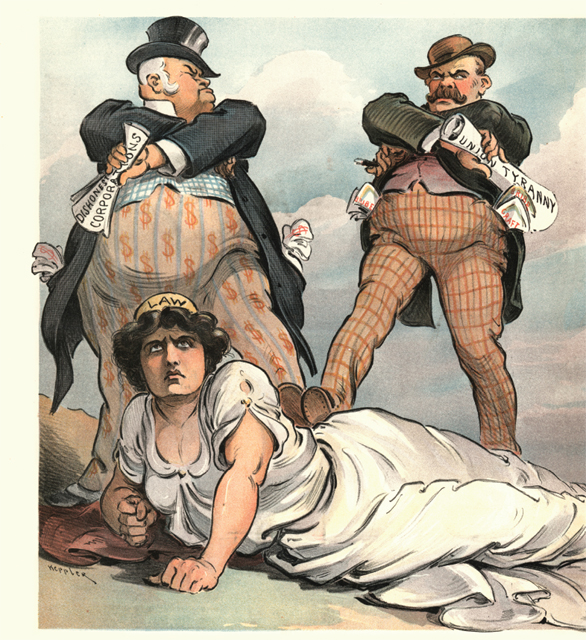

Cartoonists in the newspapers and magazines largely took up and ran with the mode of cartoon-muckraking, with pictorial treatments of predatory businessmen, aggrieved consumers, and helpless citizens. Their pictures complemented the thousands of words of journalists.

Books of fiction and reportage on the same issues proliferated. In a sense, the genre was begun by TR's disciple Jacob Riis. The Danish immigrant was a pioneer of candid photography, and a newspaper reporter with a social conscience. Horrified by conditions he discovered in Lower East Side tenements, especially in New York City's infamous Five Points neighborhood, he threw himself into reform efforts. Throughout the 1880s he lectured with magic-lantern slides in churches. Riis also wrote extensively of these shocking conditions for The New York Tribune, The Sun, and for Scribner's Monthly. In 1890 his landmark book, How the Other Half Lives, was published. It became the model for exposés of the underbelly of American prosperity, pricking the consciences of those in a position to ameliorate such conditions, and inspiring other reformers to good works. Roosevelt had sought out Riis as a mentor during his days as Police Commissioner in New York. TR once said of Riis, “The countless evils which lurk in the dark corners of our civic institutions, which stalk abroad in the slums, and have their permanent abode in the crowded tenement houses, have met in Mr. Riis the most formidable opponent ever encountered by them in New York City.” Riis returned TR's admiration. In 1904 he wrote the semi-official campaign biography, Theodore Roosevelt, the Citizen.

By the midpoint of Roosevelt's second term there were numerous magazines that heavily featured reform-oriented and investigative reporting, including Everybody's, McClure's, Cosmopolitan, The American Magazine, Munsey's, and even Collier's Weekly and The Saturday Evening Post. Roosevelt's old ally from Police Department days, Lincoln Steffens, wrote about urban corruption in The Shame of the Cities. Charles Edward Russell wrote about the Beef Trust. Samuel Hopkins Adams wrote about fraudulent medicines. Ida Tarbell and Henry Demarest Lloyd wrote about the Standard Oil Trust. Nellie Bly, the pioneering female journalist, frequently went undercover to expose various abuses. David Graham Phillips wrote about the culture of corruption in Congress in The Treason of the Senate. Burton J. Hendrick wrote about the insurance industry. Thomas W. Lawson wrote a series, “Frenzied Finance,” about the stock market.

These were the Muckrakers. TR did not coin the term, though he applied it to these writers. He originally meant it as a caution, that some writers were more concerned with tearing down than reforming, and that they could spread cynicism by exaggerations and falsehoods. He once said:

You may recall the description of the man with the muck-rake [in John Bunyan's novel of Christian symbolism, The Pilgrim's Progress], the man who could look no way but downward with the muck-rake in his hands; who was offered a celestial crown for his muck-rake, but who would neither look up nor regard the crown he was offered, but continued to rake to himself the filth of the floor….

There are, in the body politic, economic and social, many and grave evils, and there is urgent necessity for the sternest war upon them. There should be relentless exposure of and attack upon every evil man whether politician or business man, every evil practice, whether in politics, in business, or in social life. I hail as a benefactor every writer or speaker, every man who, on the platform, or in book, magazine, or newspaper, with merciless severity makes such attack, provided always that he in his turn remembers that the attack is of use only if it is absolutely truthful.

The term Muckraker stuck, but as an honorific title.

It is impossible to assess how much of the tidal wave of reform sentiment at this time was inspired by Theodore Roosevelt, and how much he merely anticipated, to some extent breaking the bronco and corralling it. No doubt he did a bit of both, for certainly such movements would eventually have begun without him.

In Congress, however, a new generation of reformers, most of whom were frank apostles of TR, immediately set a legislative agenda and did not hew to tradition in the House and Senate. They introduced bills against the wishes of senior members. So it happened that, within a few years, House Insurgents even succeeded in stripping the Republican Speaker Joseph G. Cannon of autocratic powers. Among the laws passed near the close of Roosevelt's term was the Hepburn Railroad Rate Act, to prevent railroads from discriminating against smaller businesses and farmers. When he was a rancher, TR had seen many such entrepreneurs, average Americans, squeezed out of business by collusion, favored rebates, and false rate filings of the monopolies. The Pure Food and Drug Act was passed at Roosevelt's urging, spurred on by muckraking articles and books like The Jungle by Upton Sinclair, as well as revelations of serious health violations in the meat-packing industry.

Insurgents were to Congress what Muckrakers were to the press. Their era in Congress (more active in the House) was between 1905 and 1913. They were Republican reformers with agendas derived from Roosevelt: social and industrial justice. They were Nationalists, once again in the Hamilton-Clay-Lincoln tradition, presuming that nationwide questions required national solutions. They also saw problems within Congress itself, and their targets were not Democrats as much as the hide-bound reactionary leaders of their own party, the Old Guard. Angry town halls and local elections sent Insurgents to Washington to change the way business was done on Capitol Hill. The Insurgents' era in Congress prefigured, in many ways, another generation's Tea Party grassroots revolt.

As the Insurgents felt their oats, the Old Guard dug in its heels. But history was not on the side of the Reactionaries. The Muckraking process was exposing congressional corruption old and new. In one case, Illinois senator William Lorimer was revealed to have paid bribes for his seat, and the furor was another nail in the coffin of senatorial elections by state legislators. Insurgents often held the balance of power in the House, and some Democrats joined their votes to achieve institutional reforms, such as stripping the Speaker of his simultaneous control of the Rules Committee.

Of course, the Republican Establishment in Congress (or the Old Guard, or Stand-Patters, or Reactionaries, as the nicknames evolved) were the same types of enemies of reform that TR had faced throughout his career, only with new names and different frock coats. “The opposition to reform is generally well led by skilled parliamentarians,” he wrote of them. “[T]hey fight with the vindictiveness natural to men who see a chance of striking at the institution which has baffled their greed. These men have a gift at office-mongering, just as other men have a peculiar knack at picking pockets; and they are joined by all the honest dull men, who vote wrongly out of pure ignorance; and by a very few sincere and intelligent, but wholly misguided people.”

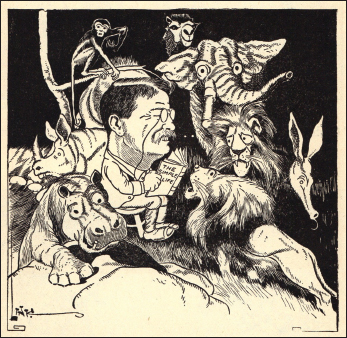

THE MOST INTERESTING AMERICAN

Besides his foreign and domestic policies, his many reform measures, and his countless other actions as president, Roosevelt has gone down in history as a fascinating individual in his own right. He captured the public's imagination even before entering the White House. Once there, he continued to inspire a certain level of awe, not only in the American people, but throughout the world. Whatever their feelings towards his policies, people could not help but be enamored of Roosevelt the man.

The Most Interesting American is the title of a book published at the nadir of TR's popularity, in 1915. While Americans might have waxed and waned in their support of Theodore Roosevelt the politician, they never lost their fascination with the man. The old naturalist John Burroughs observed that TR was a “many-sided man, and every side was like an electric battery. Such versatility, such vitality, such thoroughness, such copiousness, have rarely been united in one man.” An opponent once said, “You have to hate the Colonel an awful lot to keep from loving him.”

The man Roosevelt personified many admirable traits, and the public recognized and responded to his stellar example. He was a physical marvel, known for his advocacy of the strenuous life. He was also a man of impressive learning, more well-read than any other president, and known for his own prolific writing. TR endeared himself to the public as a family man, his loved ones—especially his children—always paramount. More than anything else, and uniting, solidifying, and supporting all the other facets of the man Theodore Roosevelt, TR possessed a staunch Christian faith. All these traits combined to make Roosevelt the most interesting American the world had ever seen, before or since.

THE STRENUOUS LIFE

The public identified with Theodore Roosevelt in many ways, but especially with his athleticism, exercise, physical regimen, sports activities, and advocacy of fitness. His conquest of childhood debilities was a story well known; his exploits as cowboy and Rough Rider would, today, be the stuff of movies, graphic novels, and television mini-series. He had been a boxer in his Harvard days (a sport he later gave up when he came to disapprove of big-money prize fights), and he befriended the champion John L. Sullivan, who became a temperance crusader after, he said, TR led him to quit drinking. In the White House, Roosevelt learned the sport of jiu-jitsu. And, as he had since college days, TR regularly boxed. He was blinded in one eye by a young naval officer, who struck TR in the temple during a match. The public never learned of it, first because Roosevelt did not want to upset the man, but also because he did not want potential attackers to know they could approach him from a “blind side.”

TR encouraged college football, saving it from bans by major schools; the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was formed in 1906, largely due to his support. Today, the Theodore Roosevelt Award is the highest honor the NCAA confers, awarded to outstanding athletes who distinguish themselves likewise in the outside world.

While other presidents had “kitchen cabinets” of social and policy insiders, TR had his “Tennis Cabinet.” He could not countenance golf, and advised his successor Taft never to be photographed on the links.

Also famous were Roosevelt's “point-to-point walks.” Whether around Sagamore Hill or in Washington's Rock Creek Park, TR led children, friends, cabinet members, and diplomats on obstacle-hikes, the main rule of which was “never around, but over or through” after setting out in one direction. That meant a lot of climbing and jumping and wading. In one famous episode, the French ambassador Jules Jusserand followed his friend Theodore on an obstaclehike, stripping down to nothing but his kid gloves in order to wade through a deep stream. When asked why he kept his gloves on, he replied, In case we meet ze ladies! More than once the president himself was seen by visitors to the park, stripped to the buff or skinned and bloodied after a challenging point-to-point.

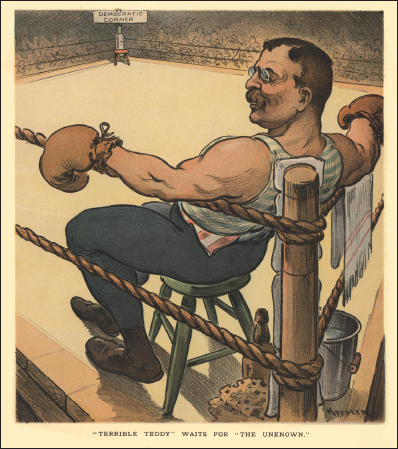

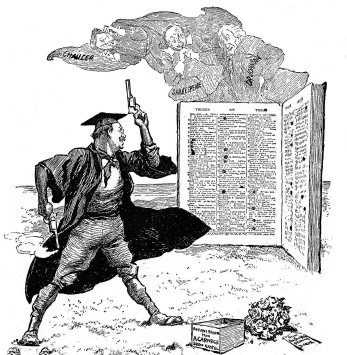

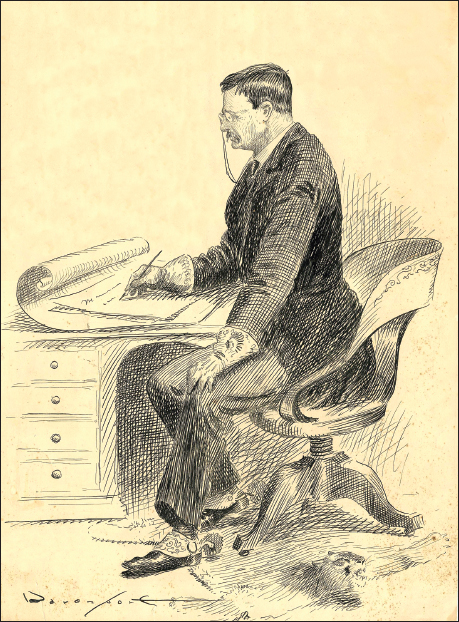

“I have no sympathy whatever with the overwrought sentimentality, which would keep a young man [coddled]. Don't flinch! Don't foul! And hit the line hard!”—Theodore Roosevelt's Harvard address, 1907. Cartoon by Billy Ireland, The Columbus Dispatch.

Two months before his second term ended, President Roosevelt received heavy criticism from Congress and some in the military about his order that Army and Navy officers be required either to ride 100 miles or walk 50 miles over three consecutive days. The 50-year-old TR decided to answer the critics by riding the regimen in one day. Was it an unreasonable rule? He would find out for himself. He ordered horse relays between the White House and Warrenton, Virginia, and “volunteered” three riders to accompany him: the White House Physician Presley M. Rixey, naval physician Cary T. Grayson, and TR's trusted military aide, Captain Archie Butt.

On the morning of January 13, 1909, at 2:30, Roosevelt ate a robust breakfast of rare steak and coffee. At 3:40 a.m., the four riders saddled up and headed east on Pennsylvania Avenue to Fairfax Court House, where they changed horses. It had been a hard winter, and the roads were icy ruts. Similar conditions and cranky horses took them to Warrenton just more than seven hours after leaving the White House. TR downed two cups of tea and thick soup, and then mounted up again.

On the return to Washington, a vicious blizzard struck. Under heavy snow, biting winds, and darkness, the ice-encrusted riders proceeded almost blindly—especially Roosevelt, who could see little without his spectacles, which were coated with ice. Once, the president's horse fell into a ditch, but both were unhurt. Sleet joined the snow as the riders approached Washington, over the Potomac's Aqueduct Bridge. They rode all the way to the White House, where Edith greeted four ice-creatures at the door. Her husband apologized for being late to dinner. It was 8:40 in the evening. When the ride was calculated, it was determined to have been 104 miles. All the men were in fine shape the next day, and the president's critics were silent, if not happy.

TR was not a mere physical-fitness crank. He believed that the strenuous life found its counterparts in morals, and that a flabby society revealed a culture in decline. “I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires more easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.”

A MAN OF LETTERS

Some of the letters TR exchanged were unorthodox. For one thing, he had a problem spelling simple words, although he could generally master longer words and many scientific and biological terms. Also, he had the handwriting of a child, a sloppy child at that, compared to standard penmanship of the Victorian era. Perhaps these peculiar challenges led Roosevelt, around 1906, to join the crusade for Simplified Spelling, a fad promoted by Andrew Carnegie and others. It was basically “fonetic speling,” an attempt to wash the vestiges of Germanic and Romance rules from American English. TR even ordered the Government Printing Office to adopt Simplified Spelling, but this was perhaps the shortest-lived of any Roosevelt reform.

Burton Link in The Pittsburgh Press. With all his activities, and under He could and often did read a book a difficult conditions, TR read at least two books a week while on safari.

However, as a literary man, TR was certainly the most well-read of American presidents, Jefferson not excepted. He could, and often did, read a book a day. He was what a later generation of teachers called a “speed reader.” His retention was astounding, and his range of interests encyclopedic. Theodore Roosevelt wrote more than fifty books, and his magazine articles covered all manner of subjects. While he was president, he wrote a scholarly article on ancient Irish sagas. After leaving office he wrote lengthy art criticism of the famous Armory Show, where Cubism had its debut in America. When his son Kermit introduced him to Children Of the Night, an obscure book of poems, TR was so impressed that he wrote a favorable review for a major magazine, sought out the starving poet, and arranged a government job, with instructions to “think poetry first” and bureaucratic pencil-pushing second. Thus was the career of a major American poet, Edwin Arlington Robinson, begun.

Roosevelt wrote many works on American history. Without setting out to do so, because they were written or assigned in random order over many years, he eventually covered the sweep of the entire national narrative. Several of his books, like The Naval War of1812 and the multi-volume Winning of the West, continue to be regarded as standard works in their field. Listed in general order of their place in the American story (not publication dates), they include: New York City, Gouverneur Morris, The Winning of the West, The Naval War of 1812, Thomas Hart Benton, and Hero Tales from American History (with Henry Cabot Lodge). Other random titles include a biography of Oliver Cromwell, the two-volume Life-Histories of African Game Animals with Edmund Heller, many collections about hunting and camping, and several anthologies of articles, speeches, and essays.

A member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Roosevelt was also president of the American Historical Association, elected just one month after his exhaustive and contentious Bull Moose campaign for the presidency.

THE FAMILY MAN

Childhood and its preoccupations are a separate, special, and very significant aspect of the man who was Theodore Roosevelt. For a man reared in the Victorian Age, when children were to be seen and not heard, his upbringing (and, in turn, the household of his own children) was remarkable. Theodore Senior and Mittie respected their children from their earliest ages, hiring tutors, imparting culture, and surrounding them with intellectual conversation and educational travels. But the parents also encouraged recreation and typical pursuits of childhood. Of course, the special concern paid by his father to TR's ailments and physical challenges inculcated a reverence for filial relationships.

The children of TR and Edith could be obstreperous—to the delight of cartoonists—but the chaos ultimately was managed. There were many stories: once, when Archie was sick in bed, his siblings snuck his pony Algonquin up the White House elevator to his bedroom. Another time Quentin, the youngest of the children, was cornered by a nosy reporter seeking news about the president, and the boy replied, “I see him occasionally, but I know nothing of his family life.”

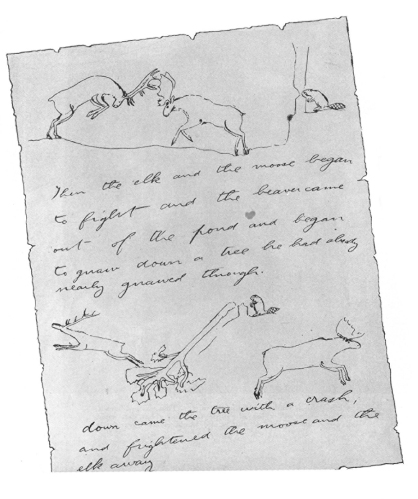

TR seldom missed his afternoon romps with the children. Every year at Sagamore Hill he would play Santa Claus for the village children, and he hosted monster fireworks picnics on the Fourth of July. Roosevelt frequently took his children, their cousins, and village friends on camping trips, which invariably included impromptu ghost stories around campfires, told with great theatrics by the president of the United States.

For all their precocity, however, there were strict rules and stern discipline for the children of the Roosevelt household. “The truth! FIRST!” was TR's ferocious priority when any dispute arose. And yet, even into their adolescent years, TR's children, sons and daughters alike, would kiss their father good-night.

Of course, all this was assisted by the fact that TR himself was still a child in many ways. Edith frequently said so, with a sigh. “You must remember,” said Cecil Spring-Rice, the British diplomat who was best man at TR's second wedding, “the president is about six.” When Roosevelt was fifty-four and planned a trip into the Brazilian Wilderness—where he charted a major, previously unknown river and almost died in the process—he dismissed warnings, saying it was his “last chance to be a boy.”

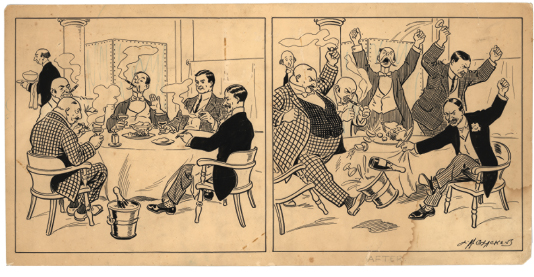

When Alice Roosevelt married Congressman Nicholas Longworth, America had an advance taste of celebrity-obsession, paparazzi, and media buzz. Alice and Nick thought they were used to attention, but they became the subject of everyone's talk for some time. A T. S. Sullivant cartoon humorously depicted their trials immediately after the White House ceremony. Reproduced from the original artwork for the New York American.

TR's children were all gifted and interesting in their own rights, but Alice stands out as one of the great American women of her time. She was famously independent—never perfectly comfortable with her second mother—and was America's sweetheart in her early White House years. She was beautiful and rebellious; she smoked, rode in automobiles to parties (imagine!), and fell into fountains while romping with friends. The popular song “Alice-Blue Gown” was dedicated to her. TR once said, “I can run the country, or I can control Alice. I cannot possibly do both.” Her parents thought that sending her on a diplomatic mission in 1905 to the Far East with Secretary of War William Howard Taft would cool her off, but on the trip she fell in love with a delegation member, Congressman Nicholas Longworth. They married in a lavish White House ceremony, and Longworth eventually rose to be Speaker of the House. (The Longworth House Office Building is named in his honor.) Alice remained a fixture of Washington life for decades.

The wit of “Princess Alice” was sharp and frequently quoted. She mimicked President Taft's wife (whom she resented for scheming against TR), and performed devastating impersonations of her cousin Eleanor Roosevelt. She was a clever and effective campaigner against both the League of Nations and intervention in World War II. Late into her life she was constantly in demand at Washington social functions, and always a source of copy—a genetic predisposition. She never voted for her distant cousin FDR, whose politics she despised, although she was not enamored of every Republican. Told that 1940 GOP nominee Wendell Willkie was a “grass roots” candidate, she replied, “Yes. The grass of a thousand country clubs.” Once her car escaped a fender-bender with a taxi, and the cabbie called Alice's driver a “black bastard.” Alice rolled down her window and called the cab driver a “white son of a bitch.” After she underwent two mastectomies late in life, she took to referring to herself as “Washington's topless monument.”

When I was a college student in Washington, D.C., I was privileged to meet Princess Alice, and luckier still to be invited to her Dupont Circle townhouse where I saw the famous sofa pillow with the embroidered legend, “If you can't say something good about someone, come sit next to me.” She died in 1980 at the age of ninety-six, and is buried in D.C.'s Rock Creek Cemetery, near the site of TR's many obstacle-walks. She remained fanatically devoted to her father all her life, even when her husband ran as a Republican from Taft's Ohio district during the 1912 Bull Moose campaign. Longworth lost by approximately 100 votes, which Alice cheerfully accepted as due to her influence.

At the other end of the spectrum of siblings was Quentin, whose group of friends, including Charley Taft, son of the Secretary of War, and boys from the local public school Quentin attended, dubbed themselves the White House Gang. In a solemn ceremony, they once voted the president of the United States an honorary member.

A MAN OF FAITH

An important aspect of TR that curiously has been neglected by history is his fervent Christian faith. In some ways, he might be seen as the most Christian and the most religious, at least the most observant, of all the presidents.

A list evaluating presidents by this rubric would be subjective at best, and a difficult one to compute and compile. Putting TR's name at the top might surprise some people, yet that surprise might itself bear witness to the nature of his faith. It was privately held, but it permeated countless speeches, writings, and acts. His favorite Bible verse was Micah 6:8, “What doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?”

Theodore Roosevelt was a member of the Dutch Reformed Church. He participated in missions work around New York City with his father, whether the charity was churchrelated or “personal,” public or private—it was all God's work. TR taught weekly Sunday school classes during his four years at Harvard. Throughout his life he wrote for Christian publications. During the White House years, Edith, a strong Episcopalian, invariably attended her denomination's church across Lafayette Park, the “Church of Presidents.” The president himself usually walked a little farther to worship at a humble German Reformed church, the closest he could find to the faith of his fathers.

Roosevelt called his 1912 bare-the-soul campaign speech announcing his political principles “A Confession of Faith.” Later he closed perhaps the most important speech of his life, the clarion-call acceptance of the Progressive Party nomination, with the words: “We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord!” That convention featured evangelical songs and closed with the hymn, “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

He titled one his books Foes of Our Own Household (after Matthew 10:36) and another Fear God and Take Your Own Part. He once wrote an article for The Ladies' Home Journal, “Nine Reasons Why Men Should Go To Church.” After TR left the White House, he was offered university presidencies and many other prominent jobs. He chose instead to become Contributing Editor of The Outlook, a small Christian weekly news magazine—tantamount to an extremely popular ex-president today (if we had one) choosing to edit WORLD magazine, instead of a higher-profile position on a mass-circulation magazine. He accepted a salary approximately one-eighth of salaries offered by magazines like Collier's that hoped to snag TR's services.

His first essay for the magazine, telling the public why he chose to associate himself with the journal, was quoted by The New York Times, citing The Outlook's “paying heed to the dictates of a stern morality,” and its “inflexible adherence to the elementary virtues of entire truth, entire courage, entire honesty.” And, he added, it had no taint of Yellow Journalism.

Roosevelt was invited to deliver the Earl Lectures at Pacific Theological Seminary in 1911, but declined due to a heavy schedule. Knowing he would be near Berkeley on a speaking tour, however, he offered to deliver the lectures if he might be permitted to speak extemporaneously, not having time to prepare written texts of the five lectures, as was the custom. It was agreed, and TR spoke for ninety minutes each evening—from the heart and without notes—on the Christian's role in modern society.

TR was not perfect, but he knew the One who is. Fond of saying that he would “speak softly and carry a big stick,” it truly can be said also that Theodore Roosevelt hid the Word in his heart and acted boldly. He was a great American because he was a thoroughgoing good man; and he was a good man because he was a humble believer.

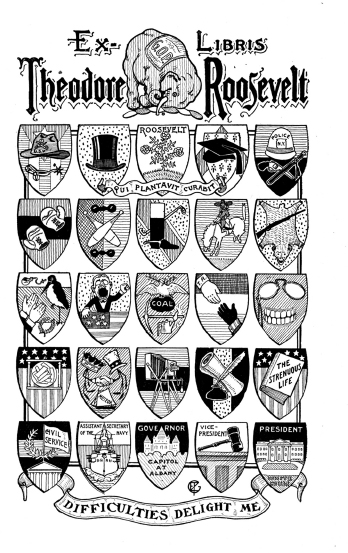

1901-1908: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

AT THE DAWN OF

THE AMERICAN CENTURY