BIG-GAME HUNTING

IN AFRICA…AND IN POLITICS

As the Roosevelt administration drew to a close, it was clear that the majority of the American public still admired, and even revered, TR. He received ? ? many expressions of support: newspapers urged another term in the White House; his staff and “Tennis Cabinet” saw no reason to have America “switch horses”; out in the hinterlands, babies were being named for him. The New York Times—a Democrat paper—ran the only comic strip it ever published in its long life, The Roosevelt Bears.

An increasingly influential congressional bloc—Republican insurgents, many of whom were in the freshman class of 1906—argued that the progress of reform would be interrupted if TR retired from the scene. Indeed, those freshmen formed the core of the GOP's increased numbers in Congress after the midterm election. Midterm gains by the party in power were (and are) rare; TR's personal popularity, and his vision for the nation (which had come to be called, collectively, “My Policies”) received the credit.

The nation was not in a mere trance. Many people considered Roosevelt's guidance in the face of gathering storm clouds to be essential. Roosevelt's policies were designed to ameliorate society's growing disparity in wealth, to control abuses in areas of health, safety, and natural resources, and to increase national defense. A true leader, he worked to anticipate and solve national problems so that they never became crises.

But there were divisions growing in his party, as well as in the country. TR was a lame duck after his 1904 statement refusing to succeed himself in 1908. He was an ever-easier target of the entrenched Old Guard that opposed his reforms. Senators and congressmen committed slights in Congress when his messages were transmitted, and those politicians increasingly ignored his nominations. TR responded by increasing the number and length of his messages, and he increased his executive orders. More then previously, he went over the heads of Congress to the people when public pressure was necessary—the “bully pulpit” for presidential persuasion. Thus, a financial panic and short-lived recession in 1907 hurt Wall Street and Main Street, but not Pennsylvania Avenue. It was clear that the American public not only loved, but trusted, Theodore Roosevelt.

Many of his avid supporters wanted TR simply to declare his intentions, one way or the other, about the 1908 elections. His followers, the reform wing of the Republican Party, had leaders waiting in the wings, and they needed a cue if there were to be an entrance call for any of them. But TR's 1904 pledge not to succeed himself decided the issue…as did his natural restiveness. He needed to move on, and he thought it would be best for the nation, too. His first choice for successor was Elihu Root, cabinet member and New York legal legend, a brilliant advocate and administrator who had been one of the signatories endorsing young Theodore Roosevelt for the New York State Assembly back in 1881. TR knew, however, that Root's Wall Street connections would make him anathema to reform voters. Roosevelt nevertheless was tempted to choose him, because Root was a superb advocate: when his clients were big corporations, he served them well; if his client were the American people, he would serve them just as well. But politics doesn't work that way, and TR knew it.

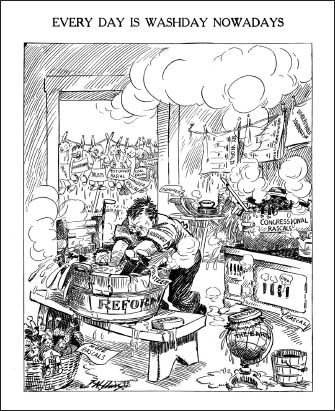

By the end of Roosevelt's term, despite his “lame-duck” status, the president advocated a passel of reforms, and contended with opponents more than ever.

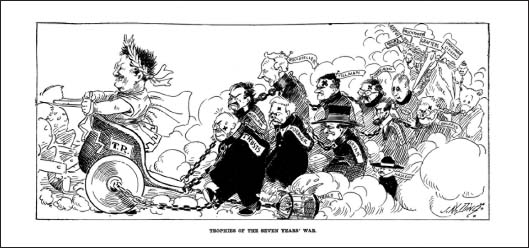

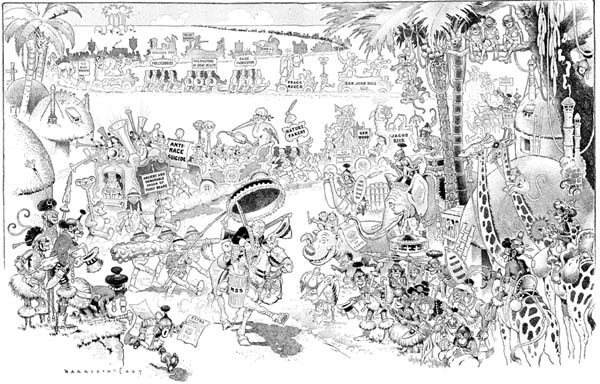

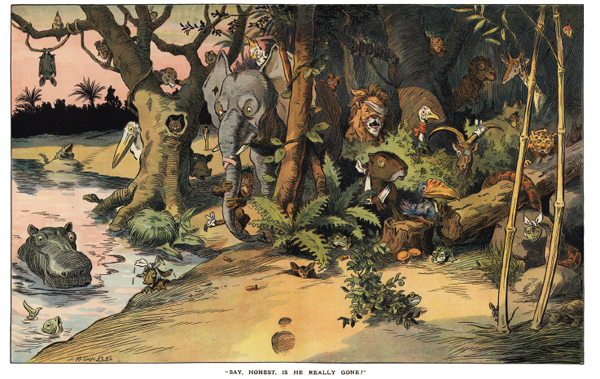

When the Greatest Show on Earth Reaches Rhinoceros Corners

Harrison Cady (in Life, 1909) imagined TR and an entourage of friends, opponents, and controversies following him to Africa.

Instead, TR tapped another loyal lieutenant and excellent administrator, the gargantuan William Howard Taft. The 325-pound Cincinnatian, hardly a member of TR's actual “Tennis Cabinet” but otherwise an old friend, had served in a variety of diplomatic and judicial posts under Harrison and McKinley, and was TR's Secretary of War. The genial Taft invariably endorsed Roosevelt's political agenda—“My Policies.”

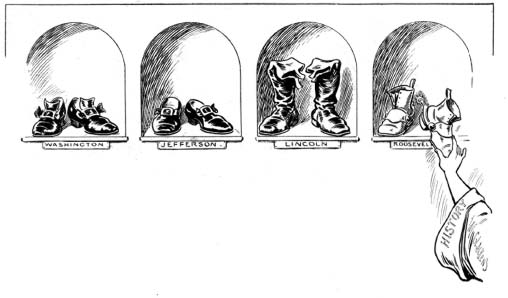

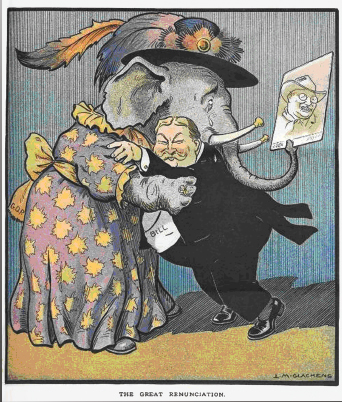

In the first issue after Taft's election in 1908, Puck ran this L. M. Glackens cartoon. “Unfilled Shoes” was not a slight to Taft but a show of respect (from a Democrat paper) and prediction about a remarkable president. Significantly, these are the four presidents who were still regarded as the Greats when Mt. Rushmore was completed in 1941.

The tacit support of President Roosevelt was as effective in blocking other candidates' end runs around Taft as his enormous girth would have been in a crowded hallway. Cartoonists had fun at Taft's expanse; one of them drew Taft from behind, on a speaker's platform, and labeled him “Big Built Aft.” His massive size, along with such characteristics as his narcoleptic traits and famed lack of energy, made him lovable to the public. Mostly, however, Taft's nomination was assured by a nod from the president.

The Democrats almost compliantly nominated the quadrennial loser William Jennings Bryan for the presidency—a third attempt. His defeat was widely forecast. TR did not give the election proceedings his full attention, though. Except for anxiety that Taft did not press his own case strongly enough on the campaign trail, the president's focus was on other matters. Among a raft of social, not political concerns, TR pressed for spelling reform and ordered government documents to be spelt in the new way; he attacked nature writers who ascribed false characteristics to animals (“nature fakirs,” he called them) ; he advocated large families and inveighed against “race suicide,” sending letters of congratulations to parents of large broods; he reviewed books of poetry; he wrote essays on ancient Irish sagas…and he planned for the adventure of a lifetime in Africa.

Taft waddled his way to a smashing victory. Roosevelt, knowing that his own personality tended to eclipse other political figures in the firmament, even a large new president, reckoned that withdrawing from the United States, not just its political landscape, would help his successor establish an independent identity. Seeds of fascination planted during his boyhood trip up the Nile, as well as promptings of seasoned hunters, put an African safari in his sights. The American Museum of Natural History (of which his father was a founder) and the National Museum of the Smithsonian Institution arranged to sponsor the trip and commission the acquisition of specimens of exotic and perhaps unknown species. The legendary hunter-tracker R. J. Cunninghame led the expedition; others included naturalist Edmund Heller, explorer Frederick Selous, and, for a time during the 11-month safari, the legendary conservationist and taxidermist Carl Akeley. Theodore's own son Kermit, almost twenty, joined the expedition as hunter and photographer. In all, scores of naturalists, hunters, assistants, and native handlers comprised the party, transporting hundreds of crates holding everything from canned foods to photographic equipment and materials for analysis, skinning, and preservation of specimens.

Also included in the cargo were eighty of TR's favorite books, to be read around nighttime campfires or under the scorching sun's rests—specially bound to withstand the effects of blood, sweat, and gun oil. This “Pigskin Library” added yet another phrase to the Rooseveltian lexicon and cartoonists' drawings. Americans flocked to emulate TR's “required reading” on their home shelves. Included in his list were the Bible and the Apocrypha; several plays of Shakespeare; Mahan's Sea Power and Macaulay's History; the Iliad and Odyssey; Chanson de Roland; Nibelungenlied; Lowell's Biglow Papers; poems of Emerson, Longfellow, Tennyson, and George Cabot Lodge; the Tales of Poe; Milton's Paradise Lost and Dante's Inferno; Autocrat of the Breakfast Table by Oliver Wendell Holmes; Luck of Roaring Camp by Bret Harte; Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain; The Pilgrim's Progress by Bunyan; The Federalist Papers; Vanity Fair by Thackeray; Our Mutual Friend and Pickwick Papers by Dickens; Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass by Carroll; Darwin, Huxley, and biblical commentaries; Omar Khayyam; Don Quixote; Montaigne's essays; and Moliere and Goethe.

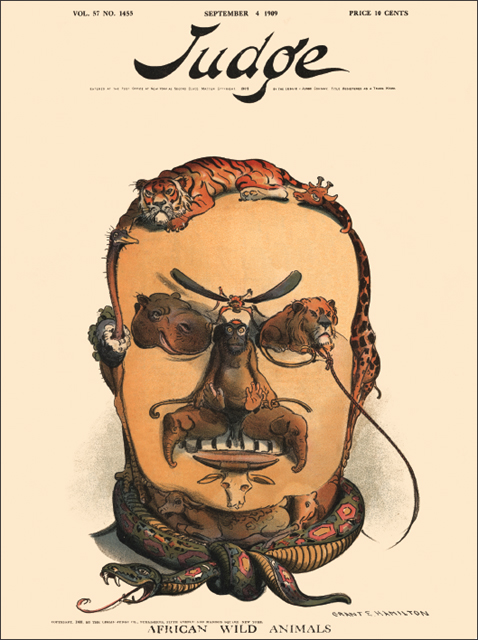

The party made its way through “darkest Africa”—South East Africa to the headwaters of the Nile—for almost a year, and the world heard little from the former president during that time. Reporters were admonished in the strongest terms to respect TR's privacy, and no news reports emanated from those jungles and plains throughout 1909. The safari of another big-game hunter, the cartoonist and war correspondent John T. McCutcheon of The Chicago Tribune (the “Dean of American Editorial Cartoonists”), met up with TR's expedition to share adventures for a few days. But back home, McCutcheon's confreres were in the dark about TR's activities. They were free, of course, to speculate, and they did, joyously. Numerous cartoons depicted vicious beasts running and hiding from the approaching “Bwana Tumbo,” the inexact but colorful appellation bestowed by American cartoonists. (McCutcheon reported that “Bwana Tumbo” really meant “Master with the Stomach.” TR heard himself referred to as “Bwana Mkubwa,” which means “Great Master.”) Some cartoonists took as themes the remark of a reactionary senator who “expected every lion to do his duty.”

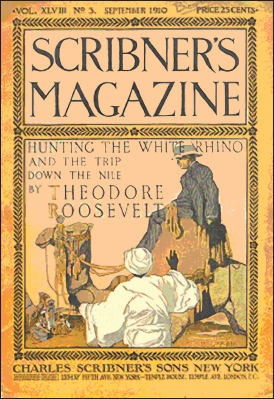

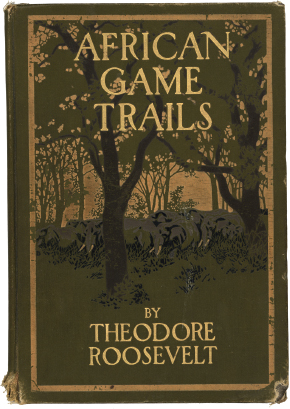

But the Colonel (TR's post-presidential title of preference) prevailed against beasts and disease. The party emerged in Khartoum, having identified, bagged, and processed for museums more than 11,000 specimens—from insects and tiny relatives of elephants to rare white rhinos and actual elephants. The expedition relied on game for their sustenance, during the course of collecting specimens for science and educational display, its major goal. TR wrote his accounts methodically day by day in longhand while on safari. Equal parts adventure and natural science, African Game Trails was serialized in Scribner's magazine and became a bestseller in book form.

After twelve months without her beloved husband, Edith joined Theodore in Khartoum. Following a few very private days with his wife, the Colonel slowed down not one bit. He traded khakis for formal attire, pith helmet for top hat, and commenced a prearranged tour of Europe. The world, which had become enamored of this American phenomenon—his reputation advanced as much by photos and cartoons as by news accounts—wanted to see Roosevelt for itself.

Predictably, the world got Theodore Roosevelt to the nth degree. In Cairo he lectured Egyptians on the pursuit of modern civilization and the British on colonial responsibilities. In Italy he and Edith stopped at the Porto Maurizio villa of her sister Emily, thence to Rome where he desired an audience with the pope. There had been, however, a local dust-up between the Methodist mission (which had referred to the Pontiff as the Whore of Babylon) and the Vatican, which warned the former president that if he called on the Methodists he would be unwelcome at St. Peter's. In a saltier variation of “a pox on both your houses,” TR boycotted both with no regret; no one would dictate conditions to him. In Paris, he lectured at the Sorbonne; in England, at Oxford (the Romanes Lecture on the subject “Biological Analogies in History”). In Christiana (now Oslo), Norway, he formally received his Nobel Peace Prize and delivered a lecture, “International Peace,” an early call for a league to enforce peace. (It should be noted that the draft of the League of Nations a decade later, Wilson's document that was long on rhetoric and short on sovereignty, was a perversion distinctly unacceptable to Roosevelt.) In Germany, TR reviewed the Imperial Army on horseback with Kaiser Wilhelm, who afterwards sent a set of photographs of the two, with humorous captions by the Kaiser, in English, on each photo's verso.

All in all, TR later said, he eventually felt that if he met another royal personage he would bite him. Many of them were dullards who gossiped about their fellow monarchs—their fraternal war of 1914-1918 was a few short years away—or complained to him about their spouses.

King Edward of the United Kingdom died during TR's tour of Europe's capitals and castles. President Taft designated Roosevelt the official American representative to the observances. It proved to be a bizarre display—the last flowering of Europe's ancient monarchies, a gaudy parade and funeral resplendent of pretty ritual and petty rivalries. It is hard to believe that a short century ago, two countries, the United States and France, were the only republics among such an assembly of the world's countries. Roosevelt's frock coat and top hat stood out amongst jewels and robes, sashes and decorations, at every turn. He continued to display a plain republican's disdain of the pomp…with his trademark sense of humor.

The French representative with whom he shared a coach in the procession approached the Colonel “with tears in his eyes, tears of anger,” TR later wrote. “The other guests had scarlet livery, and…ours was black. I told him I had not noticed, but I would not have cared if ours had been yellow and green. My French, while fluent, is never very clear, and it took me another half hour to get it out of his mind that I was not protesting because my livery was not green and yellow.” The Colonel's accounts to friends and family of the European tour were hilarious—typical of his self-deprecatory and absurd streaks in table talk and correspondence. They were traits that endeared him to the public, and especially to cartoonists and print humorists.

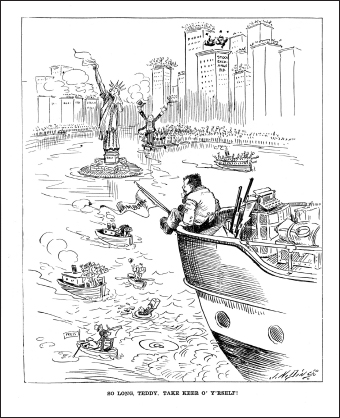

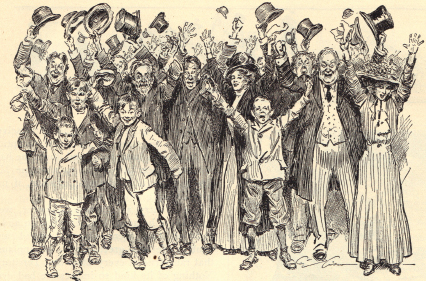

Charles Dana Gibson spoke for a broad cross-section of Americans—and drew them—in his Collier's cartoon “Hurrah for Teddy!”

In the world's eyes, the whole show of the Royal Funeral was overshadowed by Theodore Roosevelt. Standing apart and above, he truly seemed to be the First Citizen of the World. It was with that new title on his résumé—added to his pedigree as American aristocrat, cowboy, scholar, soldier, hero, crusader, reformer, ex-president—that he returned to his native New York City.

As the only president born in New York City, TR's literal homecoming was impressive.

The parade through Manhattan was the grandest the city had seen, and has been matched by few since: Lindbergh's 1927 tribute and the 1969 New York Mets perhaps are the only rivals. Thousands of citizens thronged the streets, even remote side streets. Celebrities of all sorts were on the reception committee and mingled in the adoring crowd. There were government figures and diplomats, police and honor guard, Upper West Side social-register types, and Lower East Side immigrants. And there were also many roughhewn cowboy friends and Rough Riders from every corner of the nation. Thunderous rapture echoed through the concrete corridors; confetti and banners were everywhere.

Reporters and friends, however, noted a solemnity to TR's response. “The world was at his doorstep!” But Roosevelt replied that it was a characteristic of every great wave that a depression, and often a contrary undertow, followed. He believed the more avid the adulation, the more inevitable the rejection that would come later. TR felt the legendary Roman “public slave” behind him in the carriage, holding a wreath just off his head and whispering, Sic transit gloria mundi—the world's acclaim is fleeting.

The Colonel faced many challenges, not the least of which were the expectations of his followers. He was fifty-one, an age younger than most presidents at the beginning of their terms. Professional employment seemed to be his least worrisome challenge; he was offered university presidencies, book contracts, even editorship of major newspapers. He accepted the invitation to serve as contributing editor of The Outlook, a small Christian weekly of opinion and current affairs. Its pages became his primary platform, and its offices his New York City headquarters for several years. Up until now, TR's inheritance and activities had allowed him to live comfortably, but as he wrote, “I had enough to get bread. What I had to do, if I wanted butter and jam, was to provide the butter and jam, but to count their cost as compared with other things.” His work at The Outlook, as well as some freelance work, gave him independence of action and the reasonable confidence of a secure income, so that he would be able to pass something along to his children.

Yet there was one seemingly intractable challenge, beyond his control…perhaps. In a little more than a year, his successor in the White House had proven a hapless, and even hopeless, failure. Even presidents elected by huge majorities—and Taft's victory was even greater than Roosevelt's had been four years earlier—can be politically tone deaf, display faulty leadership skills, and have a short memory of campaign promises. They can obsess over selective causes that confuse the public, dismay supporters, and waste the currency known as “political capital.” In those terms, Taft was headed for political bankruptcy in the eyes of many people, friends and foes alike.

President Taft was woefully inept at keeping party factions together—where TR had been a master. Both factions besought Roosevelt's assistance after his return to America.

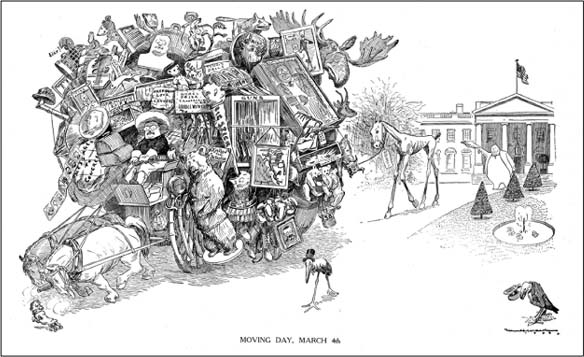

Such was the state of the White House upon the Colonel's return to America. Anxious and panic-stricken friends had sent letters to him in Europe, chronicling the situation. Worst of all for Roosevelt personally, Taft had drifted—some said he had hurried—away from TR's policies.

“My Policies” were now being depicted by cartoonists as abused puppies or discarded baggage. Roosevelt valued those policies because he believed they were vital to America's progress. He believed that his reforms had solved many of the nation's ills, and that the continuation of such policies would avert problems and even prevent disasters like social upheaval. America was growing more radical, in cities, on farms, and within labor unions and immigrant groups. As always, TR saw the best antidote for socialism in what he called (with Lincoln as his inspiration) “sane radicalism.” Cartoonists and humorists hit the nail on the head every week: “Taft carried out Roosevelt's policies…on a slab,” was one of the jabs. “President Taft is an amiable island surrounded by men who know what they want,” proclaimed another. TR's supporters—allies of many years' battles as well as fresh activist reformers in the Rooseveltian mold—pleaded with the Colonel to defend the causes and revive his policies—that is, to re-engage in politics.

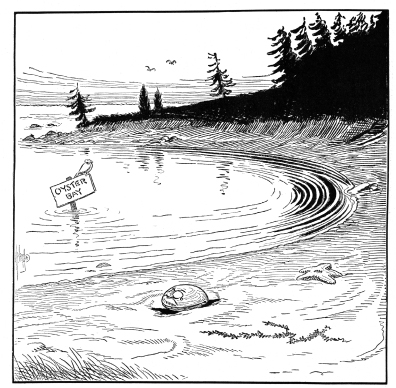

When Roosevelt returned from Africa and Europe to find his successor's administration in turmoil, and TR's old allies pleading for a defense of the Square Deal policies, he determined that he would study the situation and not cause trouble for Taft. He pledged that for a month he would stay shut “like a native oyster.” A difficult challenge for someone of Roosevelt's temperament. A cartoon by Billy Ireland of The Columbus Dispatch.

After TR's return from Europe, he responded to these contrary tugs on his loyalty and influence. He announced that on political subjects he would return to Sagamore Hill and “close up like a native oyster” for two months. He needed to assess the situation, hoping that Taft's policies were not reversals but merely different routes to the same goals. TR also sincerely desired to say nothing that could be interpreted, much less misinterpreted, against his protégé. For someone of TR's temperament, this time in seclusion was more daunting than long cattle drives, fighting Spaniards, or facing a charging elephant in the jungle. But the stakes were higher.

It was excruciating. “Will” Taft was a longtime friend whom TR loved, a man he had trusted. But Taft had dealt him innumerable personal slights. (Many were actually committed by Mrs. Taft, who never hid her disdain for Theodore and Edith.) Taft cemented alliances with TR's enemies, and there were numerous public rollbacks of reform measures and reformers. Gifford Pinchot, the nation's chief forester, exposed corruption in the Interior Department. Pinchot's revelations bordered on insubordination, and Taft sided with the Department secretary, Richard Ballinger. Pinchot was dismissed, widely seen as a sum betrayal of TR's conservation policies.

Even in one of the few areas where Taft maintained the Square Deal reforms—“trust busting”—Taft's Attorney General implied that TR had looked the other way when U.S. Steel and other corporations acted to help solve the Financial Panic of 1907. The indolent Taft did not seek Roosevelt's point of view before the charge was made public; he had not thoroughly vetted all the matters appertaining; and he had not even bothered to read the legal papers, which were certain to be bombshells. The nub of the matter was that financiers during the panic had sought assurance that their assistance would not later be second-guessed or penalized. Roosevelt assented, with the knowledge and approval of advisors—including cabinet member Taft. Taft had never objected to the initial action his administration now undertook to investigate; his timing seemed designed to embarrass TR politically. Besides, Taft showed disloyalty to TR at a time when the Colonel was straining to maintain his support of the president. Perhaps worst of all was the implication, not that Roosevelt had been complicit in any illegal act, but that he had been duped by Wall Street barons.

The acts of Taft's Justice Department were bombshells. With that issue added to the others, Roosevelt found himself in a difficult position. Under Taft's inept banner, the Republicans had suffered massive defeats in the midterm elections of 1910, losing control of both houses of Congress and many governorships. The only insurgent who stepped forward to challenge Taft for the 1912 presidential nomination was Wisconsin Senator Robert M. LaFollette, a quirky radical who espoused myriad causes, seldom inspiring a large following. His campaign to challenge Taft collapsed when he himself collapsed, losing control at a newspapermen's banquet and ranting abusively at his hosts for hours until the room emptied of embarrassed listeners.

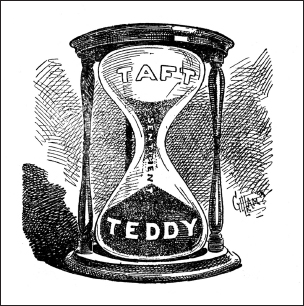

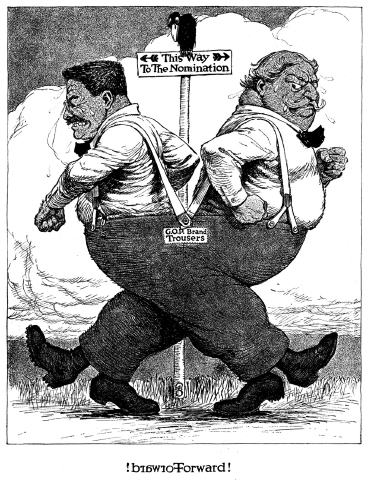

The course of the primaries, by Victor Gillam in The Denver Times.

What had seemed like heresy to the Colonel at first now became a virtual duty: to challenge Taft for the GOP nomination. Republican officeholders, major newspapers, reformers and academics, a host of political cartoonists, and especially average citizens (as always, the constituency most special to TR) combined to create a recruiting-call that was irresistible.

Roosevelt realized that if he ran for a third term now, he risked defeat and jeopardized his place in history. It would be political suicide. His closest friends urged him to hold back. He should let Taft bumble through a second term or probable defeat, and in 1916 if that was his goal. But TR was not interested in this kind of personal calculation; he wanted to meet the challenge head-on, advance his principles, and lead the causes he championed. If ever TR displayed purity of purpose, devoid of raw ambition, it was in his 1912 campaign.

The limitation of one president to two presidential terms was a tradition that originated with George Washington's disinclination to succeed himself more than once. To many Americans, Washington's admonition against more than two presidential terms was sacrosanct. Ulysses S. Grant had unsuccessfully surveyed a third term, and it was a perennial, if not quadrennial, topic in politics. TR understood the trepidation, but maintained that a third non-consecutive term—especially if the public approved by election—removed any danger of entrenched influence or institutional abuse. The four terms of TR's distant cousin Franklin later prompted the adoption of the two-term amendment to the Constitution, not long after death ended FDR's marathon presidency in 1945.

Ultimately, the third-term issue, though significant, was not the major component of the opposition to TR in 1912. It was, rather, a convenient stick picked up by establishment Republicans with which to beat back the advance of reform that TR represented. It is remarkable that many conservative Republican office-holders and newspapers openly dismissed Taft's chances of re-election, yet were willing to lose with him, instead of winning with a reformer like Roosevelt. Such was the reaction against the rising tide of reform and the desperation to maintain control of the party apparatus, and to transform their basic disrespect of Taft into his humiliation.

With friends such as his “supporters,” Taft still had the congressional insurgents to deal with. Almost all of them Republicans, they were largely a party within a party, and their relationship with GOP hierarchy was often strained. The group had no one identifiable chief, but many superb leaders. It subscribed to no specific charter or manifesto, but it shared common convictions and agreed to a basic, ambitious battle plan. Insurgents believed that centralized federal power held the answers to many of the problems they sought to solve, and they swore ultimate devotion to the common citizen—the unfettered individualist, able to make his or her way in the world according to God-given talents and personal responsibility. This was the type of citizen TR praised in speech after speech.

Roosevelt was still viewed as a party leader, an Establishment man, despite his reformist ways, until after the 1910 midterm elections. With a foot in both camps (the established GOP and the Insurgents) he tried to hold the Republican Party together, believing it to be the best vehicle to effect reform. The hostility of Old Guard leaders, and the effective indifference of Taft, as much as changing social and political conditions, nudged TR closer to seeing the necessity of rescuing “My Policies.”

A substantial portion of America, their concerns voiced by the Insurgents, thought that President Taft was tempting revolution by looking backwards, and that Theodore Roosevelt could be—must be—empowered again to steer the nation between the two extremes of reaction and radicalism, to reform. Senators were still elected by state legislatures, not the general public, and were widely seen as “bought and paid for” by special interests. Unelected, unaccountable, and often untouchable judges were overturning hard-fought and popular laws. In response to such crises in representative governance, Roosevelt advocated the initiative, the referendum, the recall, and political primaries. These are now standard throughout the land. He favored extending voting rights to women, and was the first major politician to do so. He favored child-labor laws and workplace safety regulations, which reforms were seen as intrusive to capitalism's operation by many reactionaries of the day.

When court decisions that did not affect Constitutional matters were opposed by a majority of the public—that is, when the legislative and judicial branches disagreed—TR advocated a reform that would grant the public the ability to vote for the recall of judicial decisions. When Roosevelt proposed this reform, many of his Old Guard supporters, including longtime friends like Henry Cabot Lodge and Elihu Root, withheld their support from him, fearing that recalls of judicial decisions would lead to the recall of judges…a step on the road to mob rule, in their eyes. TR's position was that the Constitution did not create one branch to be superior to the others, and when two branches disagreed, the public (after safeguards like cooling-off periods, for certain categories of legislation) could vote to decide the issues affecting them.

In the pages of The Outlook, TR pressed his case. During a national speaking tour, in Osawatomie, Kansas, birthplace of John Brown, he defined his evolving creed as “The New Nationalism.” Speaking before the Ohio State Legislature, he detailed his views of the initiative, the referendum, and the recall. In a speech in Carnegie Hall, he delivered his “Confession of Faith.” Each step of reform was more radical, to be sure; yet he constantly gained support. Unlike many politicians, he drove his points with increasing clarity, not weasel-words (another of his phrases seized upon by cartoonists): he wanted supporters and opponents alike to know exactly where he stood.

Seven Republican governors in early 1912 wrote a public letter entreating Roosevelt to enter the race. With that, TR “threw his hat into the ring”—yet another political term he coined, to the delight of cartoonists. Although primaries were a new phenomenon, the Republicans held many of them, and Roosevelt won the vast majority of delegates so chosen. Even in Taft's home state, Ohio, the president was humiliated, roundly defeated in popular vote and losing almost every district delegate. Clearly, TR was the choice of many average Americans. It was believed that even William Jennings Bryan, the perennial Democrat candidate, might endorse Roosevelt if his own party nominated a reactionary.

Robert Minor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch TR's explanation of his decision to run in 1912. Minor later founded The Masses magazine then quit cartooning to become a Communist Party White House. worker and political candidate.

Roosevelt attracted everyday voters in the primaries, but he did not capture the hearts of Republican bosses in the back rooms. Delegates selected by the primary method were overwhelmingly committed to TR; however, in the GOP Convention, roughly half the delegates were controlled by state organizations or areas of the country (such as the Deep South) where Republicans were scarcer than snowmen. Those delegates were in the pocket of the White House.

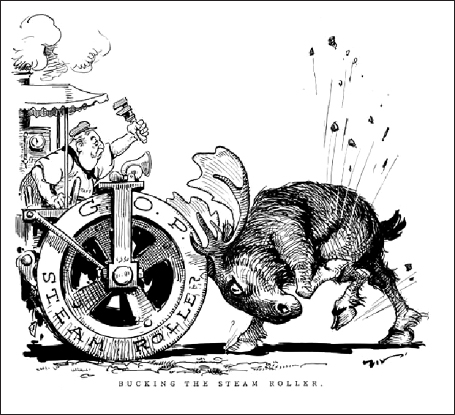

An inevitable, monumental fight loomed. The Chicago Coliseum shook with tension, and the city's streets were bursting with partisans, impromptu rallies, and fistfights. The country followed every debate, every dispute, every hearing over rival delegations and credentials. The committee deciding these contests was in the hands of the White House. Reporters and cartoonists in the press gallery monitored a steady drip-drip-drip of parliamentary outrages by the bosses. Roosevelt delegates cried, “Theft” and “Thou shalt not steal!” Observers compared the actions of the credentials committee to a methodical “steamroller,” crushing the people's will. Roosevelt partisans took to shouting “Toot! Toot!” to deride the convention. Convention organizers arranged to have barbed wire under the platform's bunting, fearing that speakers might be rushed. Theodore's eldest child, Alice—“Princess Alice” to the adoring public—attended the convention. She was 100 percent for her father, yet her husband Nicholas Longworth, the GOP congressman from Taft's home district, was loyal to the president. In typical Alice fashion, she managed to get right in the face of her childhood “uncles,” men like Elihu Root, the convention's permanent chairman, taunting, “Toot! Toot!” Taft partisans distributed phony handbills announcing, “At three o'clock tomorrow afternoon, Theodore Roosevelt will walk on the waters of Lake Michigan.”

Because of the mercurial nature of events, and the unreliable phone lines between Sagamore Hill and the Windy City, TR had decided to attend the convention, and betook an entourage by train—the first time a candidate (except for dark-horse compromise surprises) was present at his party's nominating convention. His hotel suite became a nerve center or a battle's war room, with people coming and going, emissaries trading “feelers,” and reporters and cartoonists recording every rumor and bit of news. It was all a panorama of raw politics; it was glorious theater.

Eventually, the Roosevelt forces lost. The Credentials Committee narrowly seated just enough Taft delegates to give them a convention majority. The convention as a whole, as per tradition, ratified the results. But in this unprecedented situation, the disputed delegates (most of whom were Taft supporters flouting the results of their states' primaries) in effect voted on their own legitimacy. The Old Guard entertained no doubts that they were insuring the GOP's electoral doom in the fall, but it was worth it to keep control of party machinery. The Colonel's allies—delegates in Chicago, leaders who rushed to Chicago from around the country, citizens from Thomas Edison and John L. Sullivan to humble farmers and clerks—eagerly waited for TR's response, and largely urged a “bolt”: an exodus from the corrupt party.

In those first heady days, and through the summer of 1912, TR knew he faced a grim alternative. On the one hand, he could not support the tainted nominee or platform of a corrupt process. But if he ran for president as an independent, he reckoned he would likely beat Taft but trail the candidate of a united Democrat party; and he, not the grandees of the Old Guard, would be blamed for the mess. To support the beneficiaries of political theft was unthinkable to Roosevelt—his righteousness was white-hot. Besides, the likelihood of defeat was, to this seasoned combatant, not reason in itself to avoid the contest. Ultimately, it was as a noble fighter for righteousness that he wished to be remembered by history, not as jeopardizing his presidency or wrecking the GOP establishment. His course was clear. He agreed to the insistent calls for a new organizing convention six weeks hence. He received assurance that there would be financial underpinning for a new party, and talked to his family and closest associates about the vituperation and sacrifices they faced.

Major newspapers (such as The New York Mail, Chicago Tribune, Philadelphia North American, and Kansas City Star) supported him. Governor Hiram Johnson of California and Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana were with him. They were joined by a variety of civic leaders, businessmen, celebrities, reformers, and activists, in convention assembled, ironically (or appropriately) in the very site of the Republican convention. It was a foregone conclusion that the delegates met not to deliberate, but to nominate. Some observed that they assembled as if for a coronation. The party was named the Progressive Party, but quickly became known by the cartoonists' symbol of Roosevelt's simile, the Bull Moose Party. (Newspapermen had asked him if he were up to such a fight, and he replied, “I feel as strong as a bull moose!”)

The week of fervid speeches and wild enthusiasm in the Coliseum was closer to a revival meeting than a political convention. There were many prayers and hymns sung. Roosevelt's rousing, acceptance speech (the first on-site acceptance by a major presidential candidate in American history), ended with the words, “We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord!” after which the entire convention hall broke into a spontaneous, lengthy parade around the perimeter, lustily singing “Onward Christian Soldiers.” Even Oscar Strauss of the Macy's Department Store fortune, candidate for governor of New York and a prominent Jewish leader, joined in that demonstration.

Other enthusiasts—many of the reformers and activists attracted to the movement were liberals and radicals with whom TR was not always comfortable in this fluid, coalescing alliance. They had been allies or adversaries in the past, depending on issues and tactics of the moment; and within a few years, he would harshly condemn many of them on matters of preparedness and war, socialism and Bolshevism, and pacifism. Even during the Bull Moose campaign, he referred to these supporters as the “lunatic fringe” that every popular movement attracts. Withal, the Colonel viewed them as willing allies, not willing dupes; and he soberly sought to keep the extremists from being too extreme.

Three major parties were now in the presidential field, all paying obeisance to reform—Republicans (with an ironically progressive-sounding platform), Democrats, and the Bull Moose Party. Roosevelt, the veteran, seemed to present the freshest program. Taft boasted that his trust-busting was more vigorous than TR's, which was true. The Democrats rejected several conservative candidates and nominated Wood row Wilson, the liberal New Jersey governor. Wilson, more radical than most of his supporters would have hoped, guessed, or feared, would usher in a package of statist policies and internationalist initiatives before he was finished with the presidency. Yet with this field in the race, the Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs polled almost a million votes.

OPPOSITE: Fred G. Cooper in Life portrayed the Taft-Roosevelt split. ABOVE: J. H. Donahey in the Cleveland Plain-Dealer.

TR knew the immediate prize was likely a chimera. Victory seemed doomed by electoral arithmetic, and if he were elected, he would have sparse congressional support for his program. The hastily formed Progressive Party fielded few congressional or local candidates.

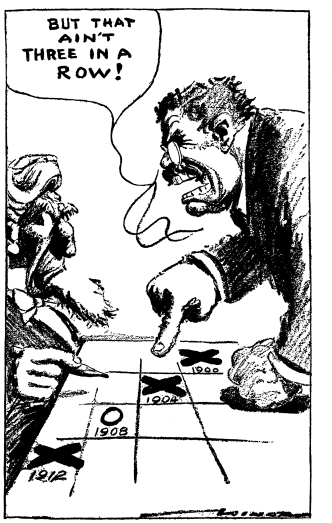

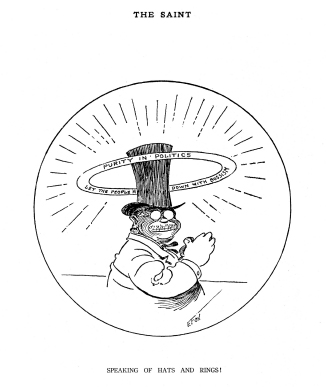

Nevertheless, Roosevelt was accused of blind ambition. Republican and Democrat cartoonists alike pictured TR as a Napoleon, the “Third-Term Candidate.” Cartoonists who had drawn him with a “T” and an “R” in the lenses of his pince-nez spectacles now lettered a first-person singular “I” in each. Pro-Roosevelt cartoonists were for the first time outnumbered, with the attacks centered less on TR's policies and more on the third-term issue. It was a drumbeat. One newspaper, The New York Sun, never referred to TR as anything but “the third-term candidate,” even in its news columns. The Colonel's defense, when he deigned to respond, was ineffectual: that he had meant that three consecutive terms were unwise for presidents; that declining a third cup of coffee should not suggest one never desired another cup; and so forth. His opponents, newspaper editorials, and political cartoons continued to peg away.

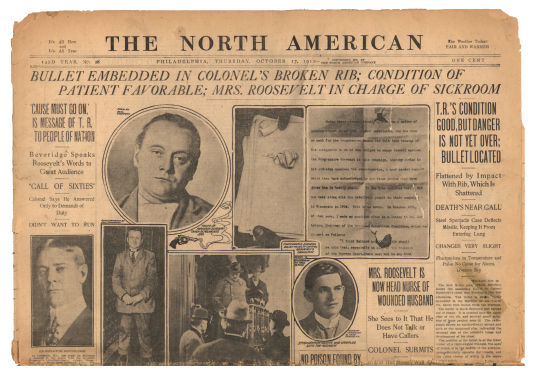

A Brooklyn bartender named Joseph Schrank was among those incited by the criticism, persuaded that TR's run for a third term threatened American democracy. He purchased a gun and followed the Roosevelt campaign to several cities. In Milwaukee on October 14, TR finished dinner at the Hotel Gilpatrick, prior to an appearance at a large rally. As he climbed into his open-top automobile and turned to wave to supporters, Schrank stepped forward and fired point-blank into Roosevelt's chest.

As TR later recounted, he was knocked back by the force of the bullet, and then demanded that the angry crowd bring the assailant before him. He made a mental observation that the gun was a .38 on a .44 frame—irrelevant as to the situation, but interesting to the hunter and soldier in him—coughed and found no blood, which persuaded him that the bullet was not in his lung; and then ordered the car to drive him to the Auditorium. Everyone pleaded with TR to go to the nearby hospital, but he sensed the moment's drama; this was an exquisite opportunity to demonstrate his sincere conviction that his candidacy was but one part of a crusade. He was a flag-bearer to be succeeded by another if need be; the fight was bigger than his own well-being. “I will make that speech or die,” he grimly informed his worried aides.

“In the long fight for righteousness, the watchword is ‘spend and be spent,'” Roosevelt had said prophetically several months earlier. “It matters little whether any one man fails or succeeds, but the cause shall not fail, for it is the cause of mankind.” When he arrived at the hall, the news of the shooting had not yet reached the packed house. He was met with wild enthusiasm, but he hushed the crowd: “Friends, I shall ask you to be quiet as possible…I don't know if you fully understand that I have just been shot…. I want to take this occasion within five minutes of having been shot to say some things to our people which I hope no one will question the profound sincerity of.” When he unbuttoned his jacket to take his speech from his breast pocket, the crowd—and TR himself for the first time—saw that his shirt front was bright red with blood. His typewritten speech, triple spaced and folded in thirds, had a bullet hole clear through it.

Indeed, the speech had slowed and slightly deflected the bullet, which had also passed through a metal spectacle-case. But ultimately, it was the Colonel's tremendous muscles that stopped the bullet, as doctors around the operating table at Chicago's Mercy Hospital, where TR eventually agreed to be examined after a train ride from Milwaukee, observed to their great surprise. For years TR had been known as an advocate of the “strenuous life” (which was the title of one of his books), a rabid athlete who exercised to the point of obsession. “It is largely due to the fact that he is a physical marvel that he was not dangerously wounded,” one doctor said. “He is one of the most powerful men I have ever seen laid on an operating table. The bullet lodged in the massive muscles of his chest, instead of penetrating the lung.”

Roosevelt delivered his speech, toward the end surrounded by aides lest the significant loss of blood manifest itself. It was a wobbly candidate who left the stage when finished, assuring his followers, “Don't worry about me…. It takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose!”

TR appreciated the irony of the assassination attempt. His entire life he had courted death, hunting in Maine's deep woods and Montana's snowy mountains, as cowboy, as Police Commissioner, as Rough Rider, as a president who assumed office after McKinley was fatally shot, as a big-game hunter in Africa. But now, the Colonel wrote a friend, “I feel a bit like the old maid who discovered a man under her bed one night and said, ‘There you are! I've been looking for you for 40 years!'”

He recovered quickly enough to make another campaign appearance less than a month later, to an overflow crowd at Madison Square Garden. Beneath banners of Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln, accompanied by running mate Governor Hiram Johnson of California, as well as an ocean of the common people who adored him—he made one last impassioned plea for the New Nationalism's platform of progressive conservatism, which he warned might be America's last chance to preserve the Republic as the founders planned it.

“Progressive conservatism,” his version of Lincoln's “sane radicalism,” was not an oxymoron but a precise program. Certainly, between the last two years of his presidency and the two years after the 1912 campaign, TR's philosophy was at its most radical. The reforms of his presidency ignited a movement of Insurgents in the GOP and in the public arena—for instance, in the pages of many newspapers and magazines—that took those reforms and accelerated them; even the Democrat Party, whose alliance with the Populists in the 1890s merged mainstream politics with radicalism, sometimes felt left behind. Disciples of TR, like Herbert Croly and Walter Lippmann (who were to found The New Republic), were now challenging and prodding their mentor.

Ever the traditionalist, especially as concerned the American “experiment” in republican self-rule, TR was so concerned about growing social unrest and the intransigence of the reactionary elite—“malefactors of great wealth,” he called them—that he was willing to find new solutions. TR essentially sought Jeffersonian ends (that is, a nation of independent and rugged individualists), but favored Hamiltonian means (a government that boldly exercised expansive, responsible power). He inveighed, countless times, against predatory wealth and corruption in high places, while remaining critical of mob rule and socialistic policies. “The sin of greed is no lesser or greater than the sin of envy,” he said. He believed the national government needed to be a referee to guarantee a level playing field—a Square Deal for all citizens. It was not a new viewpoint, but it was crystallized and energized by conditions of the day.

TR's progressive conservatism was not an oxymoron, except among those today who misunderstand history and TR's attempts to manage great social and industrial forces. There are some commentators in our day who hold that Theodore Roosevelt should be regarded, even condemned, as a father of the contemporary progressive movement, because he advocated liberal reforms (he would have said for conservative ends) in 1912, and because his one-campaign political party was called the Progressive Party.

To criticize TR for being something he was not—that is, a prophet of what modern progressivism has become—would be akin to branding progressive church suppers as subversive. He undoubtedly would condemn modern progressivism; he even condemned a contemporary progressive, Woodrow Wilson, who was to pervert many of TR's reforms, and is arguably the architect and chief culprit of the modern progressive movement. (It is interesting to note, by the way, that TR's supposed advocacy of government-run national health insurance was cited many times by liberals during the 2010 legislative wars; yet TR never advocated such a thing.)

Most of TR's predictions about the Bull Moose campaign were spot-on; he well outpolled Taft; he carried eight states to Taft's lone two; but—with the predominantly Republican nation's sympathies divided in half—Democrat Wilson was elected with a plurality of the vote. Proud of the fight he had made, TR was not sanguine about the long-term viability of the Progressive Party as a permanent vehicle.

“There are no loaves and fishes,” he later wrote.

1908-1912: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

A POPULAR PRESIDENT LEAVES OFFICE

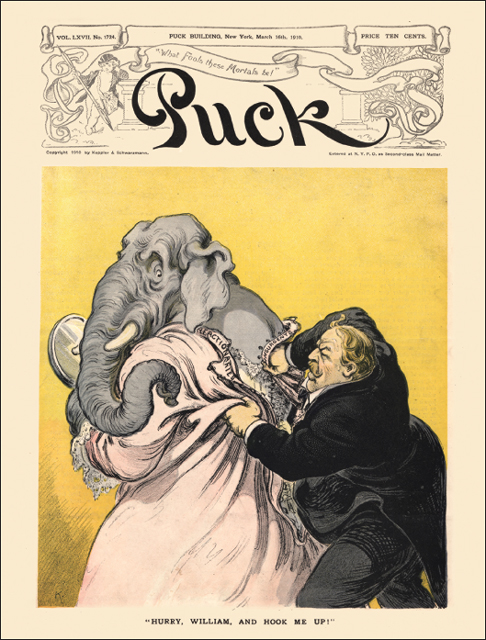

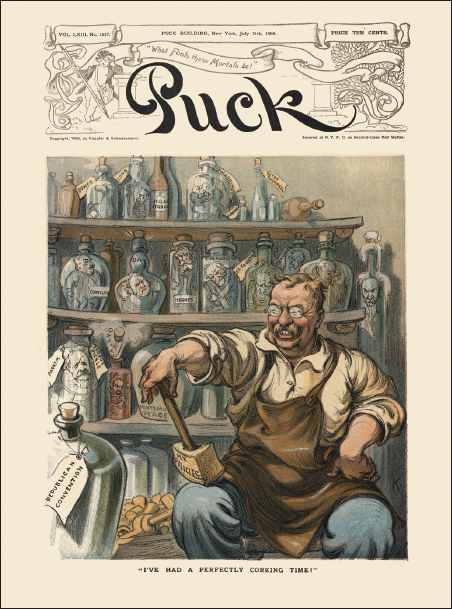

Joseph Keppler in Puck depicted TR in the last summer of his presidency. Ebullient, having enjoyed every moment of his days in office, he had met his challenges and opponents with zest—and bottled them up successfully.

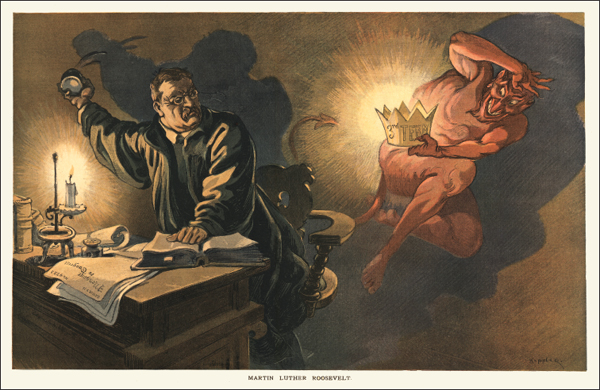

The one person who did know Roosevelt's mind about running for re-election in 1908 was TR himself. He had pledged in 1904 not to succeed himself…and was restless for new challenges. This Puck cartoon portrays TR as Martin Luther, throwing an inkwell at the devil, resisting the temptation of a Third-Term crown. From a Puck magazine printer's proof, by Joseph Keppler.

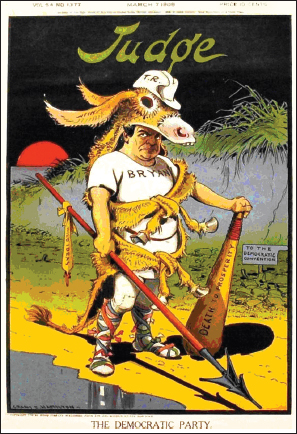

William Jennings Bryan, already twice nominated and twice defeated presidential candidate of the Democrat Party, was again nominated in 1908. Grant Hamilton in Judge depicted Bryan as a menace in donkey's clothing…and atop his head is the cavalry hat of TR—a reference to the challenge facing the Democrats: running against the Square Deal and TR's policy agenda record while both were wildly popular throughout the nation. The bitter irony for Bryan was that TR had appropriated important elements of Bryan's old platforms and adapted them to modern conditions.

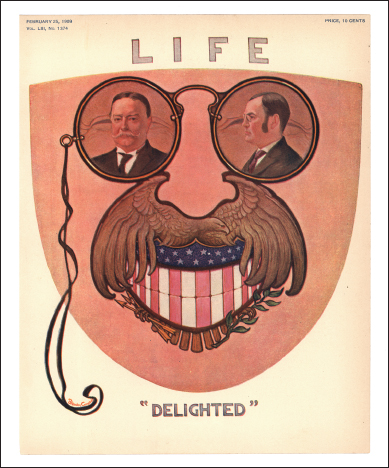

TR hand-picked his successor, his dear friend and loyal lieutenant Secretary of War William Howard Taft. The convention nominated James Schoolcraft Sherman as vice presidential candidate. Rivals for the nomination were disappointed, but such was Roosevelt's popularity that his nod was sufficient to settle the question. The cartoon on the cover of Life magazine, however, confirmed that behind Taft and Sherman—and looming larger in the public perception—was the person of Theodore Roosevelt.

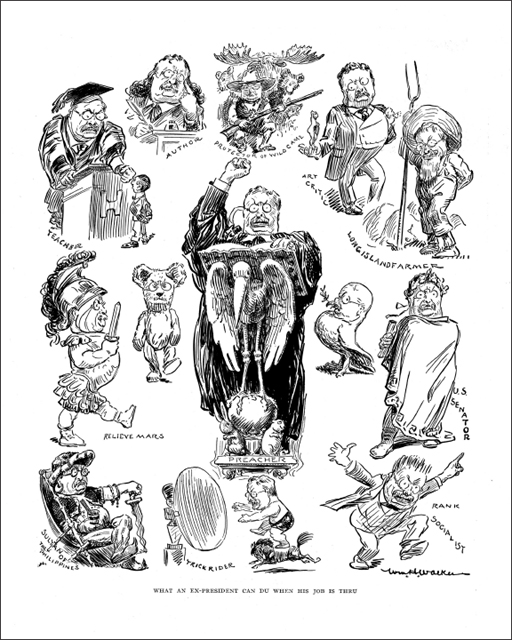

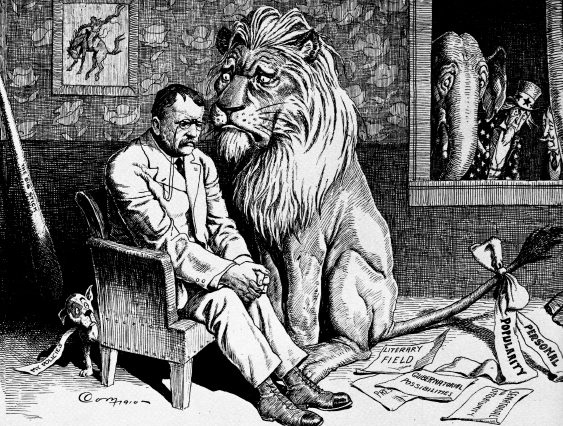

J. Campbell Cory in Harper's Weekly portrayed the dilemma, rather than the speculation, attending TR's retirement. Scattered on the floor are career options, while the Big Stick and “My Policies” are in the shadows. Indeed, Roosevelt's successor Taft would neglect those two items…to his doom and the nation's subsequent turmoil.

The caption of Cory's double-spread: “Lionization…Speculation…Perturbation. The Lion: ‘I wish I knew what you were going to do with me.' TR (thoughtfully): ‘So do I.' Chorus from window (GOP, Uncle Sam, Taft): ‘So do we.'”

1908-1912: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

A YEAR IN DARKEST AFRICA

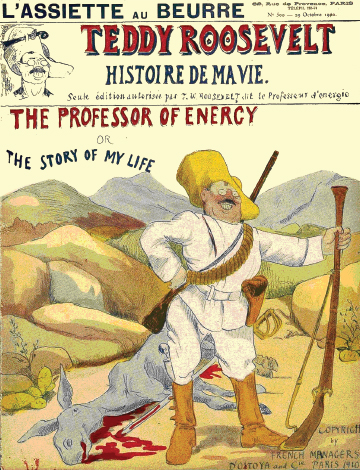

The rest of the world was as fascinated as America was by Roosevelt—the living, breathing cowboy, Harvard scholar, naturalist, soldier, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize…and big-game hunter in what was still the “dark continent.” This cartoon graced the cover of France's most notable cartoon and commentary magazine (1902-1912), L'Assiette au Beurre. Cartoonist d'Ostoya devoted a whole issue to a parody of the popular American institution, the dime novel, and drew a satirical biography of Roosevelt.

Natural history was TR's avocation, the subject of his first and last published works, and he never indulged in the indiscriminate carnage so common to his era. He savored the hunt and captured trophies, but never bagged an animal or bird except for food or study. Commonly regarded as one of America's two or three most prominent naturalists throughout his career, he would still be a prominent name in history even if natural history had been his sole career. Protective coloration, bird songs, and shared characteristics of species around the world—questions of antediluvian migration—were among his specialties. Yet cartoonists around the world found it easier to caricature the bloodthirsty hunter than to depict the laboratory naturalist. Especially when red ink was available to them!

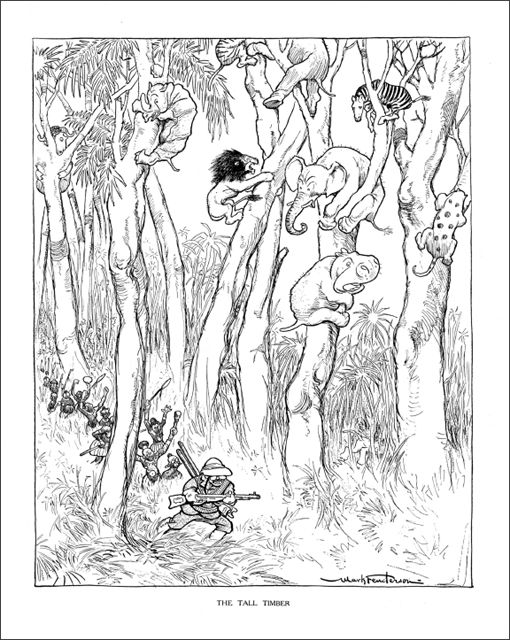

The press was strongly discouraged from following TR into the jungles, but cartoonists were free to speculate. They kept Roosevelt before the public during his year-long absence, location and status unknown. James Montgomery Flagg, who a decade later painted the iconic Uncle Sam Wants You! poster, sketched this fantasy for the cover of Life.

IN AFRICA

TR's scientific expedition to Africa was the stuff of legend—and of literature and poetry. Serialized in a popular monthly magazine, and later a best-selling book, his accounts of the safari were equal parts adventure, natural history, and some of the most colorful and memorable prose TR ever wrote.

KHARTOUM, March 15,1910

“I speak of Africa and golden joys”; the joy of wandering through lonely lands; the joy of hunting the mighty and terrible lords of the wilderness, the cunning, the wary, and the grim.

In these greatest of the world's great hunting-grounds there are mountain peaks whose snows are dazzling under the equatorial sun; swamps where the slime oozes and bubbles and festers in the steaming heat; lakes like seas; skies that burn above deserts where the iron desolation is shrouded from view by the wavering mockery of the mirage; vast grassy plains where palms and thorn-trees fringe the dwindling streams; mighty rivers rushing out of the heart of the continent through the sadness of endless marshes; forests of gorgeous beauty, where death broods in the dark and silent depths.

There are regions as healthy as the northland; and other regions, radiant with bright-hued flowers, birds and butterflies, odorous with sweet and heavy scents, but, treacherous in their beauty, and sinister to human life. On the land and in the water there are dread brutes that feed on the flesh of man; and among the lower things, that crawl, and fly, and sting, and bite, he finds swarming foes far more evil and deadly than any beast or reptile; foes that kill his crops and his cattle, foes before which he himself perishes in his hundreds of thousands.

The dark-skinned races that live in the land vary widely. Some are warlike, cattle-owning nomads; some till the soil and live in thatched huts shaped like beehives; some are fisherfolk; some are ape-like naked savages, who dwell in the woods and prey on creatures not much wilder or lower than themselves.

The land teems with beasts of the chase, infinite in number and incredible in variety. It holds the fiercest beasts of ravin, and the fleetest and most timid of those beings that live in undying fear of talon and fang. It holds the largest and the smallest of hoofed animals. It holds the mightiest creatures that tread the earth or swim in its rivers; it also holds distant kinsfolk of these same creatures, no bigger than woodchucks, which dwell in crannies of the rocks, and in the tree tops. There are antelope smaller than hares, and antelope larger than oxen. There are creatures which are the embodiments of grace; and others whose huge ungainliness is like that of a shape in a nightmare. The plains are alive with droves of strange and beautiful animals whose like is not known elsewhere; and with others even stranger that show both in form and temper something of the fantastic and the grotesque. It is a never ending pleasure to gaze at the great herds of buck as they move to and fio in their myriads; as they stand for their noontide rest in the quivering heat haze; as the long files come down to drink at the watering-places; as they feed and fight and rest and make love.

The hunter who wanders through these lands sees sights which ever afterward remain fixed in his mind. He sees the monstrous river-horse snorting and plunging beside the boat; the giraffe looking over the tree tops at the nearing horseman; the ostrich fleeing at a speed that none may rival; the snarling leopard and coiled python, with their lethal beauty; the zebras, barking in the moonlight, as the laden caravan passes on its night march through a thirsty land. In after years there shall come to him memories of the lion's charge; of the gray bulk of the elephant, close at hand in the sombre woodland; of the buffalo, his sullen eyes lowering from under his helmet of horn; of the rhinoceros, truculent and stupid, standing in the bright sunlight on the empty plain.

These things can be told. But there are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy, and its charm. There is delight in the hardy life of the open, in long rides rifle in hand, in the thrill of the fight with dangerous game. Apart from this, yet mingled with it, is the strong attraction of the silent places, of the large tropic moons, and the splendor of the new stars; where the wanderer sees the awful glory of sunrise and sunset in the wide waste spaces of the earth, unworn of man, and changed only by the slow change of the ages through time everlasting.

Cartoonist L. M. Glacken's version of TR-induced jungle

fever—Friday's footprint in reverse. From Puck.

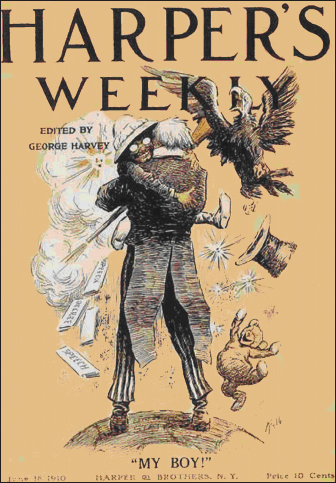

1908-1912: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE NEW NATIONALISM

To all of TR's titles and accolades, history might add “Homecoming King.” There was an unprecedented outpouring of excitement and affection when the long drought was over and the Most Interesting American was back in America. E. W. Kemble, noted as the illustrator of Huckleberry Finn and a delineator of rural blacks, was also a longtime political cartoonist. He most often opposed Roosevelt policies, and usually drew for Democrat papers. Harper's Weekly was such a publication (indeed, its editor George Harvey almost single-handedly manufactured the presidential boom of Woodrow Wilson). Yet even Kemble and Harper's Weekly put aside their animus and joined in the elation the whole country felt. “Teddy” was home after a 15-month absence. This cover cartoon is a lesson in cartoon iconography. Roosevelt can scarcely be seen, and no ID label is attached to him, yet the glasses and teeth, and an irrepressible vivacity, are enough for readers to recognize the central figure.

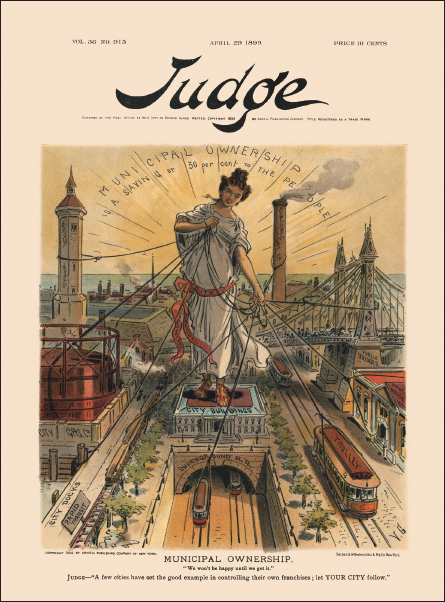

If anything illustrates the turbulent nature of political discourse during Roosevelt's presidency and the Insurgent era, it is the fact that political labels and loyalties were changing rapidly. Looking ahead to 1912, even many conservative Republicans touted their antitrust credentials. (In that regard, TR once defined a reactionary as “someone who is willing to take a progressive stand on a dead issue.”) And, surprisingly, as early as 1899, the conservative Republican magazine Judge even took a strong stand for municipal ownership of utilities, transportation, and franchises (a.k.a. socialism). Cartoon by F. Victor Gillam.

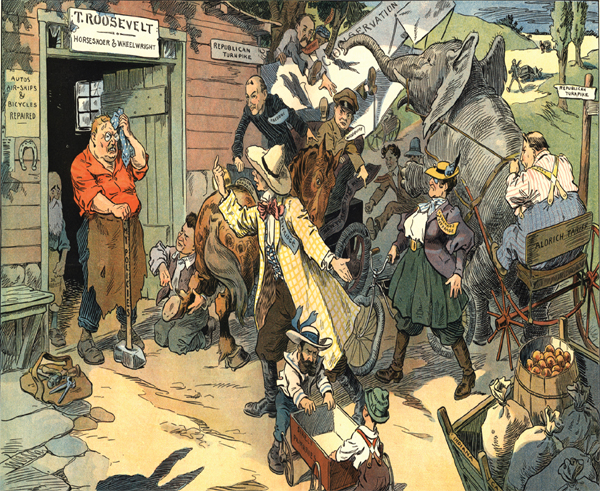

When Roosevelt returned from African wilds and European courts, Republicans of every stripe, old friends and old opponents alike, sought his assistance to repair the damage that had been done his carefully wrought work over the fouteen months of his absence. Behind TR in the blacksmith shop is Lyman Abbott, the clergyman-editor of The Outlook, the Christian news and commentary magazine whose staff Roosevelt had joined. Cartoon by L. M. Glackens in Puck, 1910.

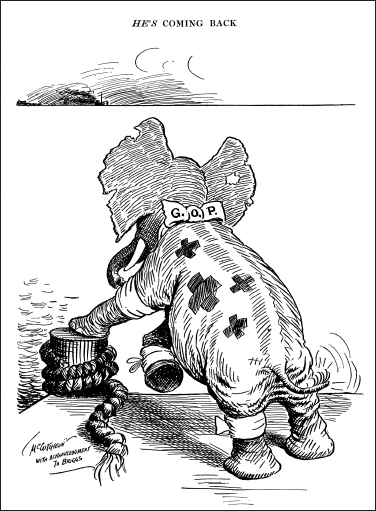

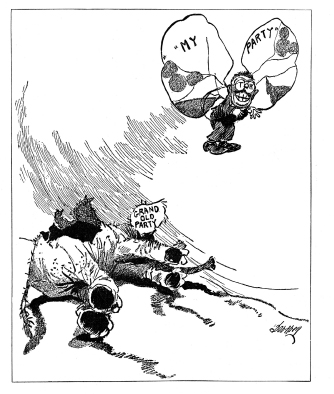

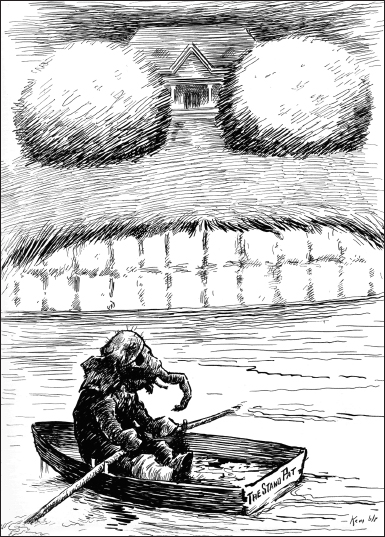

The worst elephant TR saw in the months after his presidency was not in Africa, but the Republican elephant, the cartoonist's symbol created by Thomas Nast in 1874. It had not taken William Howard Taft long to alienate the reformers and Insurgents—largely the Roosevelt wing—of the GOP. Ineptitude, a tone-deaf political instinct, and a willing alliance with the Old Guard combined to make Taft unpopular.

The party was splitting in two. In fact, America might have split in two but for Roosevelt's grounded perspicacity and thoughtful leadership as president; that he had succeeded to hold “Stand-Patters” and “Insurgents” together, and that he later corralled disparate forces during the high water mark of political ferment in 1912, means that history will never know whether America would have fared differently. Since the 1870s, agrarian reformers forced many economic and social questions; and the Populist movement swallowed the Democrat Party for two decades. Similarly, reformers and Insurgents in the GOP, who both took inspiration and provided impetus for TR's reforms, often saw the Republican Old Guard, not Democrats, as the chief foe.

This cartoon (another marvelous example of cartoon iconography) shows the battered and bloodied Republican elephant, his rowboat labeled “Stand Pat,” taking water. He looks longingly to TR's home, Sagamore Hill at Oyster Bay on the north shore of Long Island. It is a reminder of the remarkable, encompassing leadership of TR, that despite his sometimes radical initiatives as president, the party and public—and cartoonists—still saw him as leader of the conservative, as well as the insurgent, wings of the party.

E. W. Kemble in Harper's Weekly, 1910.

1908-1912: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE LEADING VOICE

OF RADICAL CARTOONING

America had a rich tradition of reformist cartooning, but in the Insurgent and Progressive years it took a turn for the radical. Its leader was Art Young. He drew for many magazines, but his work for Life and Puck grew radical until he left in 1912 for Tlie Masses, a socialist/anarchist monthly. Later, he drew for Communist publications, but also for Hearst in the latter's right-wing years; and for The Saturday Evening Post and TlieNew Yorker.

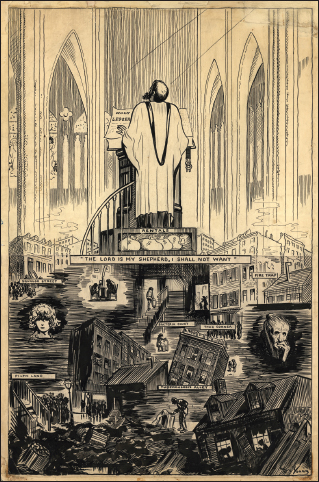

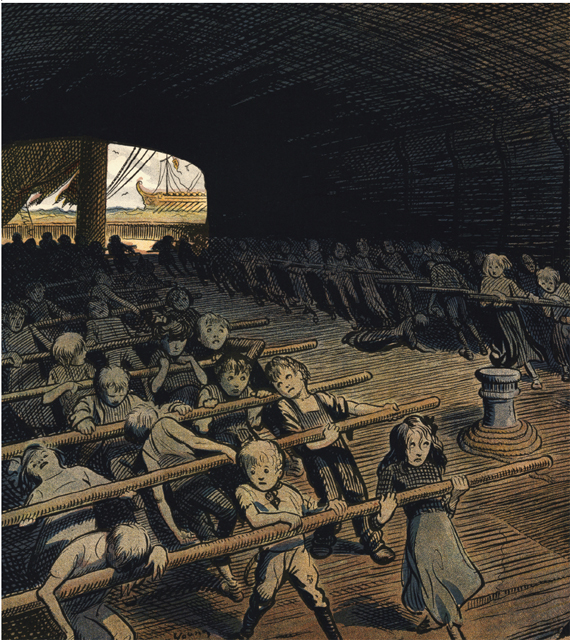

Young reported that this was his favorite of the cartoons he drew. “Holy Trinity” was inspired by muckraking articles by Charles Edward Russell, revealing the Episcopal Church ownership of New York tenements. Reproduced from the original artwork for Puck. Overleaf: A Puck cartoon by Young against child labor.

Throughout 1910, TR largely managed to avoid criticizing President Taft…while barely managing to ignore many slights, both personal and political, dealt him by his successor. However, the Colonel spoke out on issues and wrote articles, including essays and editorials for the weekly Christian magazine of politics and current events, The Outlook. He continued the same advocacies and policies—“My Policies”—of his presidency, many of them taken to new levels of urgency. When reforms were undone by the Administration—for instance, in the fields of conservation and protection of natural resources—he spoke out boldly.

TR also responded to the appeals of old friends who had supported him at crucial times in the past, and of fresh public servants who had been inspired to enter politics by Roosevelt himself. There were activists in many corners of life who had risked their careers to espouse the Square Deal and TR's philosophy.

A challenge to the Colonel's effort to bridge the camps came in the fall of 1910. The Republican Party machinery in New York State was caught in a bloody tug-of-war between the “Stand Pat” elements and the reformers. TR resisted appeals to enter the fray on behalf of the reformers, until the Old Guard laid down the gauntlet. In a gratuitous insult, the vice president of the United States, James Schoolcraft Sherman, became the nominee for the party convention's chairmanship, and he told the press that if Theodore Roosevelt (also a resident of New York) tried to chair the convention himself, he “would be beaten to a frazzle.”

No longer with a party apparatus behind the Colonel—indeed, the GOP establishment daily grew more hostile to him—but by force of personality, TR attended the state convention in Saratoga and won the convention chairmanship against Taft's vice president. Roosevelt further persuaded the convention to nominate his own preferred gubernatorial candidate, Henry L. Stimson.

Cartoonist W. A. Carson of the Utica (NY) Globe depicted the putative frazzling victim, and well portrayed TR's trademark joy of victory. Reproduced from the original artwork.

Some cartoons write, or draw, themselves. Roosevelt's Dutch ancestry, added to the “Big Stick” that he wielded in his crusades and a trademark symbol of a popular product whose ads and labels were familiar to every American, gave rise to a natural cartoon idea. Grant E. Hamilton, the longtime Art Editor of Judge, drew the pastiche during TR's cross-country speaking tour presenting the New Nationalism.

1908-1912: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE BULL MOOSE CAMPAIGN

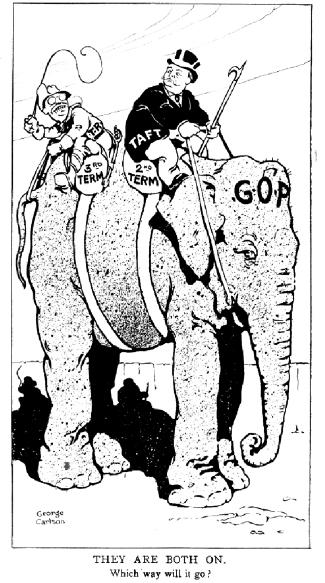

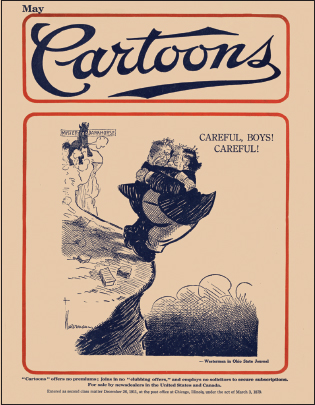

These two cartoons summarize the dilemma and the evolution of the Republican-Insurgent division during the presidency of William Howard Taft. The new president signaled his essentially conservative impulses before his inauguration, and was embraced by the Old Guard and “Stand-Patters.” But many Republicans, and many ordinary citizens, never were reconciled to TR's departure—from politics and from their daily news. The 1908 Puck cartoon could well have been published with equal application during the 1912 primaries. Henry Westerman's cover cartoon for Cartoons magazine (a monthly roundup of editorial cartoons from around the world) during that contentious primary fight was prescient: politically speaking, TR and Taft did fall off the cliff of electoral viability.

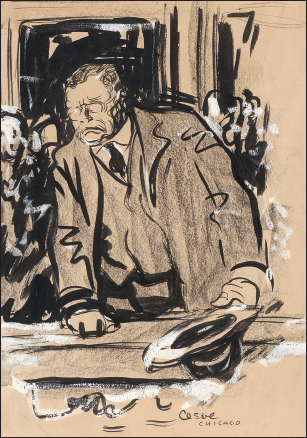

“The Thieves Shall Not Win”—Roosevelt speaking from the balcony of the Congress Hotel immediately after arrival in Chicago. A brush-and-crayon drawing made on the spot by Oscar Cesare when TR broke with precedent and arrived at a presidential convention to marshal his own forces. Reproduced from the original artwork. Cesare, a facile cartoonist who drew for many New York City newspapers through the years, including The New York Times, was married to the daughter of author O. Henry.

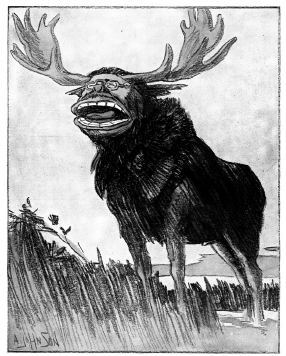

Theodore Roosevelt was a gifted phrasemaker. When he announced to newspapermen during the 1912 campaign that he felt as strong as a bull moose, perhaps he knew that he was prompting the establishment of a new member of America's political bestiary. But the pens of many cartoonists—this caricature is by A. Johnson of the German weekly Kladderadatsch—depicted TR as a bull moose.

Thereby cartoonists pinpointed one of the problems of the Progressive Party in 1912: it was not so much a revolution in American politics, but a vehicle whereby supporters could advocate for their hero as an individual.

Interestingly, party leaders and the cartoonists' icons have seldom morphed. Taft, for instance, weighed more than 325 pounds, yet cartoonists—who frequently poked fun at his size—almost never yielded to the temptation to depict Taft as the Republican elephant. Likewise neither supporters nor opponents drew Democrat politicians as donkeys. But TR frequently was depicted as the Bull Moose himself.

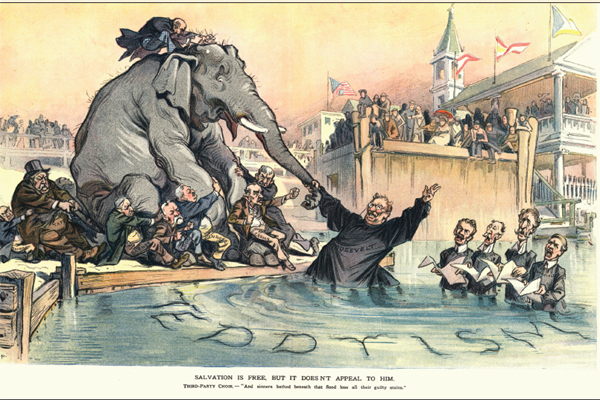

Joseph Keppler Jr., in Puck, pictures the split in the Republican Party in terms of religious revivals and Pentecostalism across America: TR is the evangelist, the GOP elephant is the sinner reluctant to be baptized. The caption is a direct reference to the camp-meeting gospel song, ‘There Is a Fountain.” From 1912, during the pre-Convention battle for the soul of the GOP.

It was Theodore Roosevelt who applied the term “my hat is in the ring” to politics. Cartoonist Fontaine Fox of the Chicago Post gave it an even more graphic description. Fox later drew the beloved Toonerville Trolley comic strip, starring Mickey (Himself) McGuire and the Powerful Katrinka.

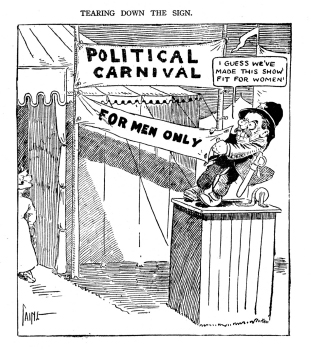

The Progressive Party was the first major American political party to endorse the right of women to vote. A cartoon by Caine in the St. Paul Pioneer-Press.

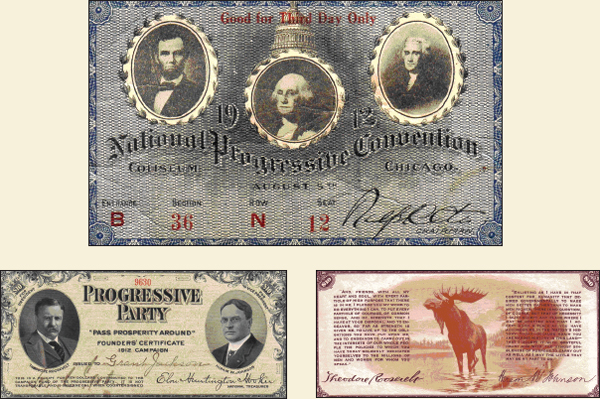

The hastily arranged nominating convention was held in the Chicago Coliseum approximately six weeks after the GOP “steamroller” did its work. Tickets were hard to secure; every night was standing-room only in the galleries, and overflow crowds stretched for blocks outside.

A unique fund-raising device was the issuance of “Founders' Certificates” whose receipts resembled currency. The candidates literally and figuratively spanned the continent: Roosevelt of New York and Governor Hiram Johnson of California. Each brought a full résumé and corps of followers. Hardly a rump protest, the Progressive Party startled America with the number of senators, congressmen, governors, mayors, and celebrities in its ranks.

1908-1912: CARTOON PORTFOLIO

THE OFFICIAL DEMOCRAT CARTOONIST

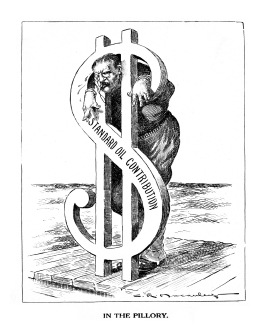

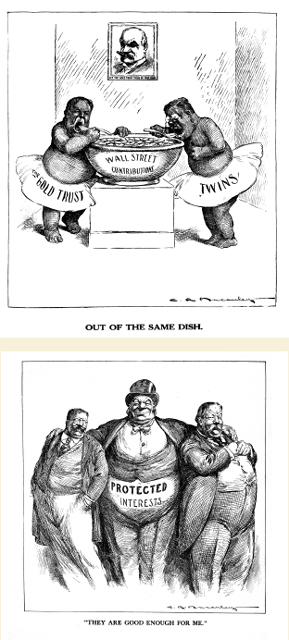

It once was the practice of national parties to hire political cartoonists and distribute their work in publicity campaigns and to partisan newspapers free of charge during campaigns. Charles Macauley was the official cartoonist of the Democrat National Committee's Pictorial Publicity Department in 1912. Then on the staff of The New York World, Macauley drew for several newspapers and magazines throughout his career, and was to win the 1930 Pulitzer Prize. In his series of 1912 cartoons, he drew TR and Taft as “the Gold Trust Twins,” parodying a popular detergent's advertising mascots; he implied that the two candidates were both tools of Wall Street.

The Democrats stirred the embers of Standard Oil's contribution to the GOP back in 1904. They flailed a Roosevelt aide, George W. Perkins, because he once worked for J. P. Morgan. But the public wasn't buying the idea that the Trust Buster was in the pocket of the trusts.

Macauley continued the meme that TR was a slave to the trusts, and parodied Davenport's famous Uncle Sam cartoon of 1904, “He's Good Enough for Me.”

Such were the levels of extreme vituperation against TR during the Bull Moose campaign that lunatics betook themselves to do violence. In Milwaukee, a Brooklyn bartender who had been stalking Roosevelt on the campaign trail shot him in the chest at point-blank range. TR insisted on delivering his speech before seeking medical attention. Later, surgeons marveled at Roosevelt's physique—his massive chest muscles absorbed the bullet, which was never removed the rest of his days.

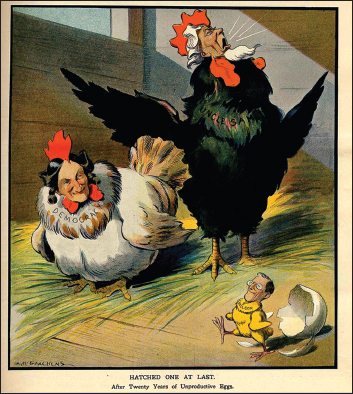

TR predicted to friends the outcome of the 1912 presidential campaign—he would beat Taft, and both would trail the candidate of a united Democrat party. Woodrow Wilson, late president of Princeton University and governor of New Jersey, was that Democrat candidate. Regarded as a Progressive, he was to give new meaning to the label—frequently different in substance and direction from Insurgent and Reform initiatives, and certainly a deviation in many respects from Roosevelt's own core beliefs. At that moment, after the rancorous 1912 campaign ended, the mother hen of the Democrat party could be pleased, as depicted in this cartoon by Glackens: Wilson's election was the first by a Democrat since the presidential campaign of Grover Cleveland in 1892.

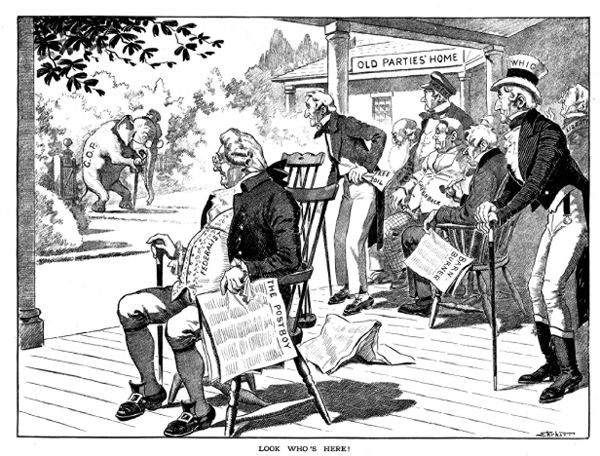

The GOP ready for retirement? A lot of people thought so after the Bull Moose campaign. The Republican Party itself had been born on the graves of several dying political movements in 1854-56; and anyone could read the numbers from the presidential election. Taft carried two states, and garnered eight electoral votes. On the other hand, the Republicans still had inertia and an infrastructure of thousands of local office-holders. The Progressives, conceived in a moment of passion, had no time or resources to build from the ground up. The elephant did not remain long in the Home for Old Parties…and eventually reconciled with the wronged TR. S. Ehrhart in Puck, 1912.

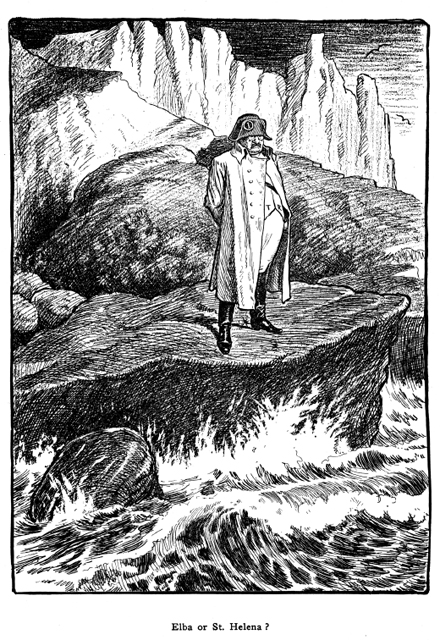

After the defeat of the Progressive Party, yet contemplating its impressive second-place showing, TR wondered if the public was through with him, or if his exile was temporary. “Elba or St Helena?” was drawn by Frank Wing of The Minneapolis Journal Wing later was a teacher of Charles Schulz.